Abstract

Objectives

Ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury after lung transplantation remains a major source of morbidity and mortality. Adenosine receptors have been implicated in both pro- and anti-inflammatory roles in IR injury. This study tests the hypothesis that the adenosine A2B receptor (A2BR) exacerbates the pro-inflammatory response to lung IR injury.

Methods

An in-vivo left lung hilar clamp model of IR was utilized in wild-type C57BL6 (WT) and A2BR knockout (A2BR−/−) mice as well as in chimeras created by bone marrow transplantation between WT and A2BR−/− mice. Mice underwent either sham surgery or lung IR (1 hour ischemia and 2 hours reperfusion). At the end of reperfusion, lung function was assessed using an isolated buffer-perfused lung system. Lung inflammation was assessed by measuring pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and neutrophil infiltration was assessed via myeloperoxidase levels in lung tissue.

Results

Compared to WT mice, lungs of A2BR−/− mice were significantly protected after IR as evidenced by significantly reduced pulmonary artery pressure, increased lung compliance, decreased myeloperoxidase and reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine levels (TNF-α, IL-6, KC, RANTES, MCP-1). A2BR−/−→A2BR−/− (donor→recipient) and WT→A2BR−/−, but not A2BR−/−→WT, chimeras showed significantly improved lung function after IR.

Conclusions

These results suggest that the A2BR plays an important role in mediating lung inflammation after IR by stimulating cytokine production and neutrophil chemotaxis. The pro-inflammatory effects of A2BR appear to be derived by A2BR activation primarily on resident pulmonary cells and not bone marrow-derived cells. A2BR may provide a therapeutic target for prevention of IR-related graft dysfunction in lung transplant patients.

Introduction

One of the most common causes of early morbidity and mortality after lung transplantation is primary graft dysfunction, which is a severe form of ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury.1 IR injury has been reported to account for up to 30% of early mortality following lung transplantation.2 Although exact mechanisms of IR-induced injury remain unclear, numerous studies have established that acute inflammation is a key feature of IR injury.

Adenosine levels are known to increase in tissues as a result of inflammation, IR, hypoxia and cellular stress. Adenosine is typically thought of as a retaliatory, anti-inflammatory response which exerts its effects via cell-surface G-coupled protein receptors, of which four sub-types have been identified: A1 receptor (A1R), A2A receptor (A2AR), A2B receptor (A2BR), and A3 receptor (A3R). The activation of adenosine receptors in different tissues has been shown to exert both pro- and anti-inflammatory responses.3 The most recent adenosine receptor gene to be identified is A2BR which is expressed on a broad spectrum of cells in multiple organs including the nervous system, intestines, lung, and heart. In the lung, A2BRs are highly expressed on alveolar epithelial cells.4 Among adenosine receptors, the A2BR has the lowest affinity for adenosine, and unlike other adenosine receptors it requires high levels of adenosine for activation that may not be reached under some physiological conditions.5 On the other hand, the expression of the receptor is induced under stresses such as injury or oxidative stress or by TNF-α.6 Some studies have suggested an anti-inflammatory role for A2BR in lung injury7 while others have shown a pro-inflammatory role.8 These contradictory results underline the complexity in defining the role of A2BR in lung injury, as it could highly depend on the exact injury conditions applied and the relative contribution of bone marrow-derived vs. tissue-derived A2BR in promoting inflammation. For instance, bone marrow cell-derived A2BRs are clear protectors of inflammation,9,10 while this might not apply to tissue-derived A2BR.

We have previously shown that activation of A2AR in the lung produces potent anti-inflammatory responses leading to improved lung function after IR.11,12 In the current study we tested the ability of the A2BR to mediate lung injury and dysfunction after IR. A2BR knockout (A2BR−/−) mice were used to demonstrate the contribution of A2BR to lung IR injury as measured by pulmonary function and cytokine/chemokine production. Through the use of bone marrow chimeras, the role of A2BR on bone marrow versus non-bone marrow derived cells in mediating IR injury was clarified.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Study Design

This study utilized 8–12-week old, male C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and A2BR−/− mice. The A2BR−/− mice have been backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 background, display a normal phenotype, and their generation and characterization has been described.9 Groups of mice (n=5/group) underwent either left lung IR or sham surgery (left thoracotomy). Preliminary analysis revealed that lung function in A2BR−/− mice does not differ from WT mice, and thus a sham group of A2BR−/− mice was not included in our comparisons. Separate groups of bone marrow chimeric mice were generated (n=5/group) which underwent lung IR. This study conformed to the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” published by the National Institute of Health (NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 1985) and was conducted under protocols approved by the University of Virginia’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

In Vivo Model of Lung IR

An in vivo hilar clamp model of IR was used as previously described.13 Mice were anesthetized using inhalational isoflurane, intubated, and ventilated at a rate of 120 strokes/min with room air (Harvard Apparatus Co., South Natick, MA). Stroke volume was set at 1 cc, and peak inspiratory pressure limited to <20 cmH2O. Heparin (20 U/kg) was injected via the right external jugular vein to prevent thrombosis during ischemia. A left thoracotomy was performed in the 3rd intercostal space. A 6-0 prolene suture was passed around the hilum using a curved 22-G gavage needle. Both ends of the suture were then threaded through a 5 mm-long PE-50 tubing. Ischemia was initiated by pulling up on the suture and thus pressing the tube against the hilum and occluding it. A small surgical clip was applied to the suture at the end of the tube to maintain tension of the tube against the hilum. The thoracotomy was then closed, and the mouse was extubated and returned to its cage. Animals were kept warm by using a heat lamp. The average time for this stage of the procedure was 15 min per mouse. After a 1 hr period of ischemia, the mouse was re-anesthetized and re-intubated. Reperfusion was achieved by cutting the suture and removing the clip and the tubing. Again the thoracotomy was closed and the mouse was extubated and returned to its cage. The average time for this stage of the procedure was 5 min. The animals were subsequently reperfused for 2 hrs prior to analysis. To minimize pain and discomfort, an analgesic (buprenorphine, 0.2 mg/kg) was administered to all animals at the beginning of surgical intervention.

Generation of Chimeric Mice

Bone marrow chimeras were produced using standard techniques as previously described.14 Briefly, donor mice (male, 24–26 g, age 8–10 weeks) were anesthetized with Nembutal (0.02 mg/g) and euthanized by cervical dislocation. Bone marrow from femurs was harvested under sterile conditions, yielding approximately 50 million nucleated bone marrow cells per mouse. The recipient mice (male, 22–25 g, age 6 weeks) were irradiated with two doses of 6 Gy each, 4 hours apart. Immediately after irradiation the mice were anesthetized using inhalational anesthesia and injected with 2–4 × 106 bone marrow cells via the tail vein. One control mouse did not receive an injection, which subsequently died to confirm the efficacy of bone marrow depletion by irradiation. Transplanted mice were housed in micro-isolator cages for 6 weeks before experimentation. The following four different chimeras were produced (donor→recipient): WT→WT, A2BR−/−→A2BR−/−, WT→A2BR−/−, and A2BR−/−→WT (n=5/group).

Measurement of Pulmonary Function

At the end of the 2 hr reperfusion period, pulmonary function was evaluated using an isolated, buffer-perfused mouse lung system (Hugo Sachs Elektronik, March-Huggstetten, Germany) as previously described by our laboratory.15 Briefly, mice were anesthetized using a mixture of ketamine and xylazine. A tracheostomy was performed, and animals were ventilated with room air at 100 stroke/min and a tidal volume of 7µl/g with a PEEP of 2 cm H2O. The animals were exsanguinated by transecting the inferior vena cava. The pulmonary artery was cannulated through the right ventricle, and the left ventricle was tube-vented through a small incision at the apex of the heart. The lungs were then perfused at a constant flow of 60 µl/g/min with Krebs-Henseleit buffer containing 2% albumin, 0.1 % glucose, and 0.3 % N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-2 ethanesulfonic acid (335–340 mOsm/kg H2O). The perfusate buffer and isolated lungs were maintained at 37°C throughout the experiment using a circulating water bath. Once properly perfused and ventilated, the lungs were maintained on the system for a 5-min equilibration period before data were recorded for an additional 10 min. Hemodynamic and pulmonary parameters were recorded using the PULMODYN data acquisition system (Hugo Sachs Elektronik).

Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL)

After pulmonary function measurements, the right lung was occluded using a surgical clip. The left lung was lavaged with 0.4 mL of normal saline. The BAL fluid was then immediately centrifuged at 4°C (500g for 5 min), and the supernatant was stored at −80°C until further analysis.

Measurement of Myeloperoxidase (MPO)

MPO levels were measured in lung tissue using a commercially available mouse MPO enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Cell Sciences, Canton, MA), and MPO levels were expressed as ng MPO per µg total lung protein. Lung tissue was homogenized in cell lysis buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Measurement of Cytokines and Chemokines

Cytokines/chemokines in BAL fluid were quantified using a Bio-Plex Mouse Cytokine Multiplex Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) as previously performed.16 The samples were analyzed as instructed with a Bioplex array reader, which is a fluorescent-based flow cytometer using a bead-based multiplex technology, each of which is conjugated with a reactant specific for a different target molecule.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Data were compared by one-way analysis of variance, followed by Satterthwaite T test for unpaired data, which provides an adjustment for unequal variance between groups.

Results

Pulmonary Function is Improved after IR in A2BR−/− Mice

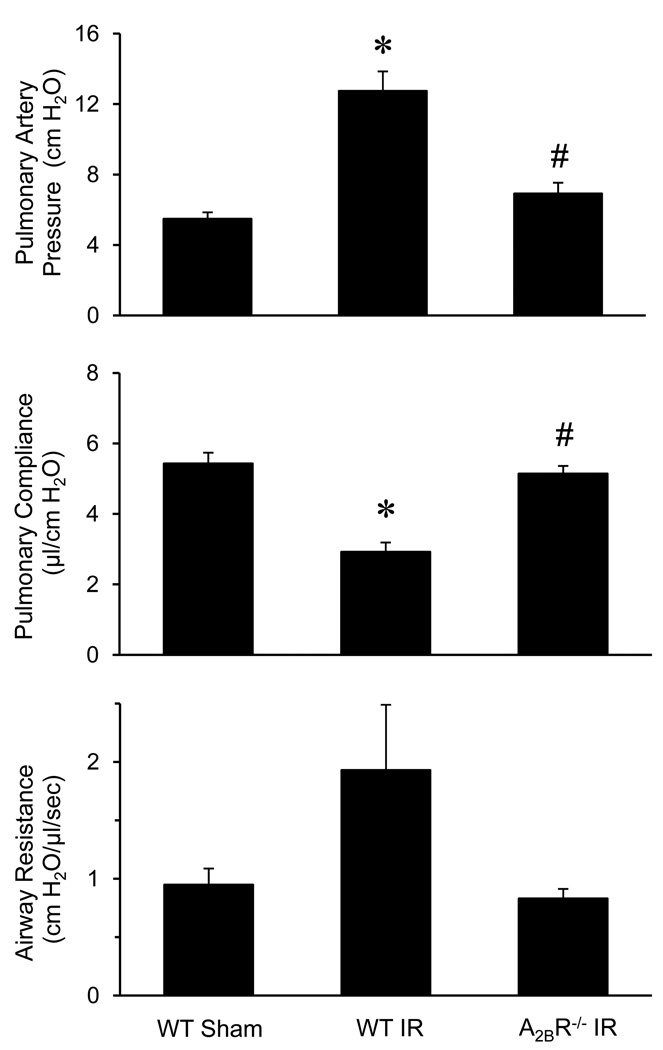

As expected, pulmonary function was significantly impaired in lungs of WT mice after IR (WT IR) compared to WT Sham mice (Figure 1). Pulmonary artery pressure was significantly increased, and lung compliance was significantly decreased in WT IR mice. Airway resistance was also higher in the WT IR mice but did not reach statistical significance. Compared to WT mice, pulmonary dysfunction was improved in strain-, age-, and sex-matched A2BR−/− mice after IR, where the A2BR−/− mice displayed significantly reduced pulmonary artery pressure, improved pulmonary compliance, and reduced airway resistance (Figure1).

Figure 1.

Pulmonary function after IR. Pulmonary artery pressure, pulmonary compliance and airway resistance were improved after IR in A2BR−/− mice compared to WT mice. *p<0.05 versus WT Sham, #p<0.05 versus WT IR (n=5/group).

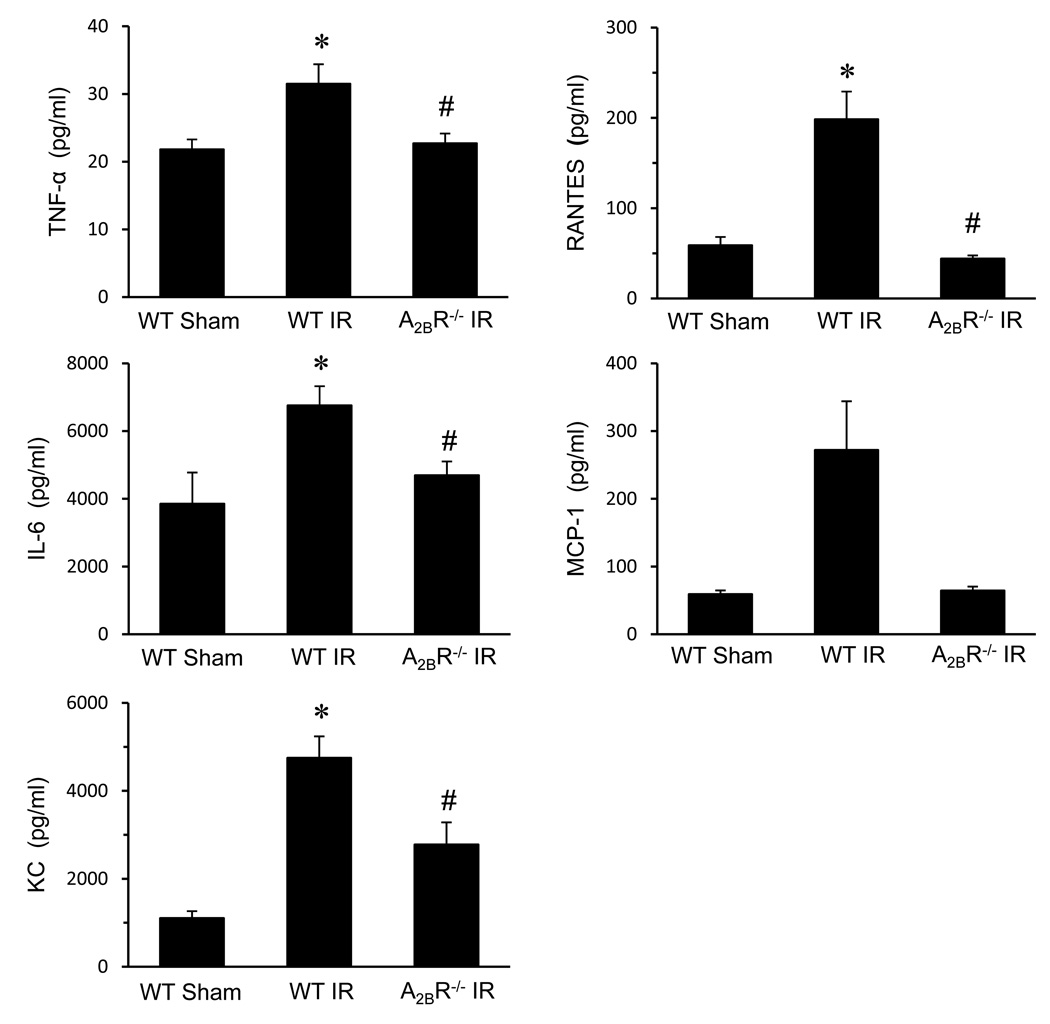

A2BR Deficiency Attenuates Cytokine/Chemokine Production after IR

The levels of TNF-α, IL-6, KC (CXCL1), and RANTES in BAL fluid were significantly increased in WT IR mice compared to sham (Figure 2). The A2BR−/− mice showed significantly reduced levels of TNF-α, IL-6, KC and RANTES after IR versus WT IR mice (Figure 2). MCP-1 level was also higher in WT IR lungs and was reduced in A2BR−/− lungs, but this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Expression of cytokines in lung BAL fluid after IR. Expression of TNF-α, IL-6, KC (CXCL1), RANTES and MCP-1 were all significantly increased in WT mice after IR versus sham. Cytokine levels in A2BR−/− mice after IR were significantly attenuated compared to WT IR. *p<0.05 versus WT Sham, #p<0.05 versus WT IR (n=5/group).

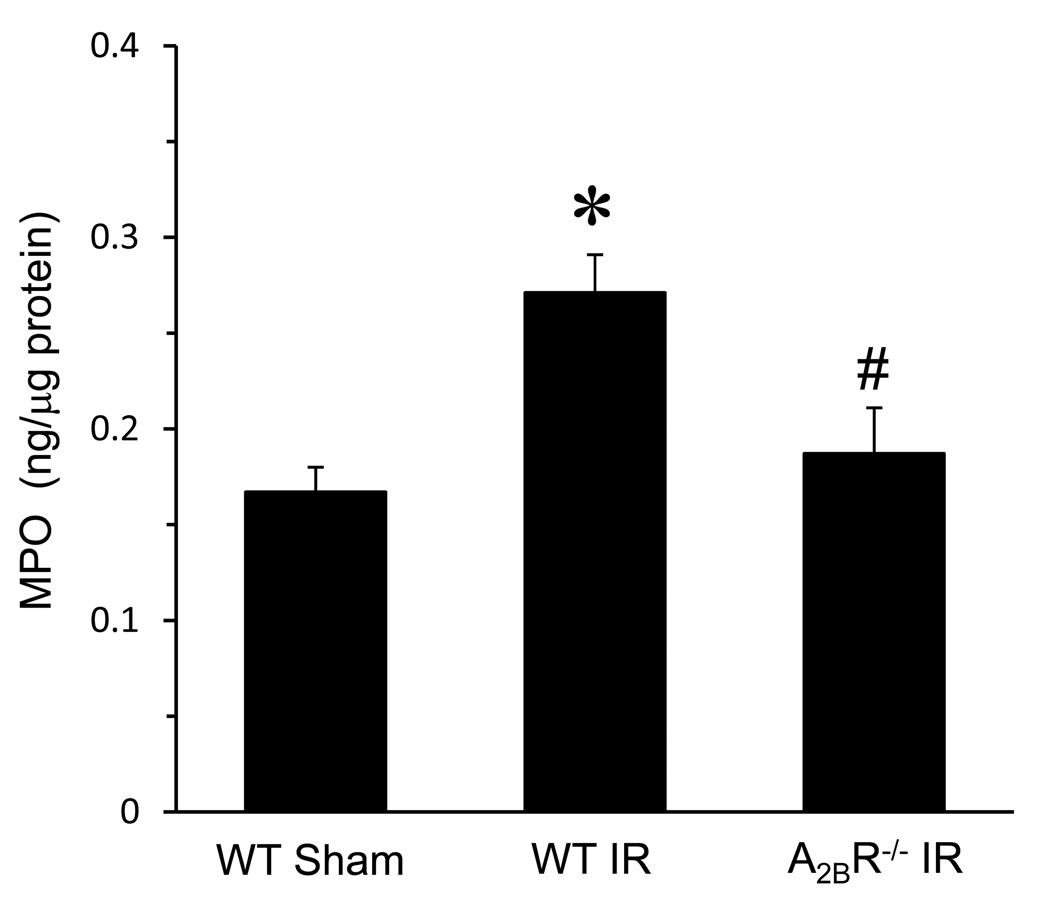

Neutrophil Infiltration after IR is Attenuated in the Absence of A2BR

MPO is abundant in the azurophilic granules of polymorphonuclear neutrophils and was used as an indicator of neutrophil infiltration in lung tissue. As expected, MPO levels were significantly increased in lungs of WT mice after IR versus sham (Figure 3). MPO levels were significantly decreased in A2BR−/− mice after IR compared to WT IR (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) levels in lung tissue were significantly elevated in WT mice after IR versus sham. MPO levels were significantly reduced in A2BR−/− mice after IR compared to WT IR. *p<0.05 versus WT Sham, #p<0.05 versus WT IR (n=5/group).

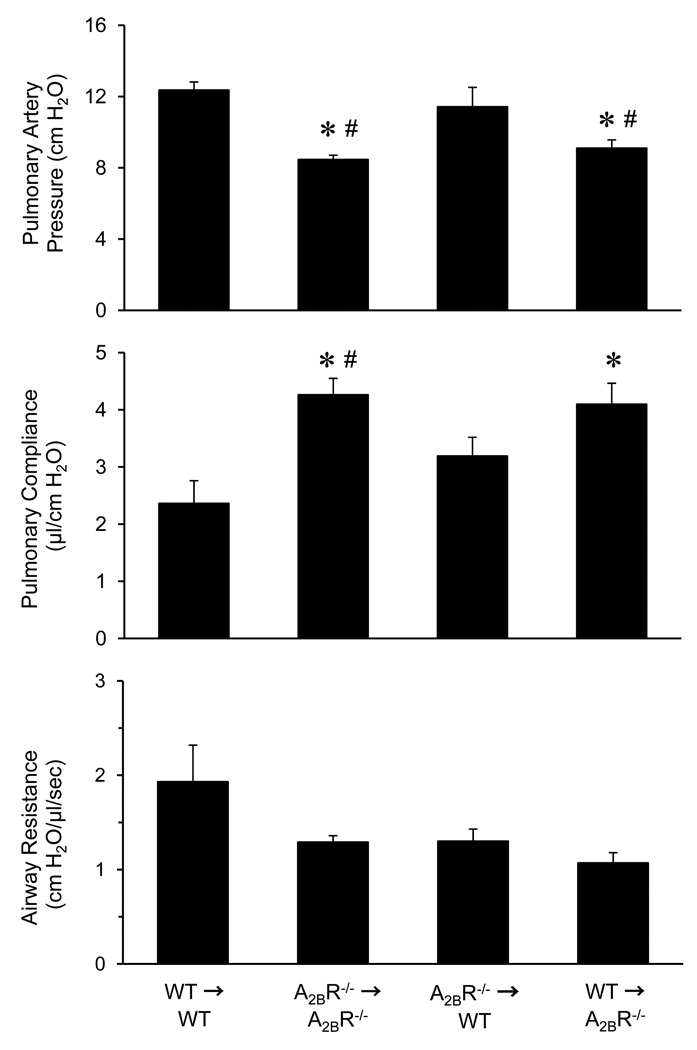

Pro-inflammatory Effects of A2BR are Mediated by A2BR on Resident Pulmonary Cells

Pulmonary function was measured after IR in four groups of bone marrow chimeras. As expected, pulmonary artery pressure was significantly decreased, and pulmonary compliance was significantly increased in A2BR−/−→A2BR−/− chimeras compared to WT→WT chimeras (Figure 4). Significant attenuation of lung dysfunction was also observed in the WT→A2BR−/− chimeras, where these mice displayed reduced pulmonary artery pressure and increased pulmonary compliance compared to WT→WT (Figure 4). No protection was observed in the A2BR−/−→WT chimeras, where pulmonary artery pressure and compliance was similar to that of WT→WT controls. Airway resistance was not significantly different among the four groups of chimeras.

Figure 4.

Pulmonary function after IR in bone marrow chimeras. All groups underwent lung IR. Pulmonary artery pressure and pulmonary compliance were significantly improved in A2BR−/−→A2BR−/− and WT→A2BR−/− chimeras compared to WT→WT chimeras (donor→recipient). *p<0.05 versus WT→WT, #p<0.05 versus A2BR−/−→WT (n=5/group).

Discussion

In this study we used an in vivo mouse model to show that A2BR plays a pro-inflammatory role in lung IR injury. We utilized A2BR−/− mice to demonstrate that A2BR gene deletion attenuates inflammatory responses in the lung after IR. Our data illustrates that pulmonary dysfunction is significantly attenuated in A2BR−/− mice compared to WT mice as evidenced by reduced pulmonary artery pressure and airway resistance and improved pulmonary compliance. In addition, lung inflammation after IR was significantly attenuated in A2BR−/− mice as evidenced by reduced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines and MPO levels.

Bone marrow chimeric mice were used in an effort to identify key A2BR-expressing cellular subsets which mediate pro-inflammatory responses after lung IR. In the WT→A2BR−/− chimeras, only bone marrow–derived cells (e.g. leukocytes or macrophages) express A2BR.4 In the A2BR−/−→WT chimeras, only non-bone marrow-derived cells (e.g. smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and epithelial cells) express A2BR.4,9,17 Our results show that lungs of WT→A2BR−/− but not A2BR−/−→WT chimeras were significantly protected after IR, suggesting that A2BRs on non-bone marrow-derived cells in the lung (i.e. resident pulmonary cells such as epithelial cells) play a predominant role in mediating the inflammatory response after IR injury.

Compelling evidence has shown that lung IR injury is mediated by inflammatory responses.18,16,13 Studies have also indicated that activated neutrophils are a primary mediator of this inflammatory response.12,18,19 The results of the MPO assay in the current study (that IR-induced MPO levels are attenuated in the A2BR−/− mice) is consistent with our pulmonary function data, suggesting neutrophil chemotaxis as a possible mechanism of the A2BR’s role in lung IR.

Our data suggest that another mechanism for A2BR-mediated pro-inflammatory responses in lung IR is through the modulation of cytokine/chemokine levels. The decrease in expression of KC, which is a potent neutrophil chemo-attractant, in the A2BR−/− mice suggests a pro-inflammatory role consistent with our MPO results. Furthermore, KC is known to be largely secreted by pulmonary epithelial cells, which supports the results of the bone marrow chimera experiment (that the A2BR’s role in lung IR is mediated through resident pulmonary cells). This suggests that it is possible that A2BR-mediated inflammation after IR is primarily directed by A2BR activation on lung epithelial cells. In addition, we observed that IL-6 levels were attenuated in the A2BR−/− mice after IR. A prior study by Ryzhov et al. demonstrated that A2BR exerts a pro-inflammatory response via secretion of IL-6,20 which is consistent with our observations.

The role of A2BR in modulating inflammatory responses to injury is complex and remains controversial. Studies have shown both pro- and anti-inflammatory responses for A2BR depending on the model and tissue used. A pro-inflammatory role of A2BR has been reflected in several studies.21–24 For example, it has been shown that stimulation of A2BR exerts a pro-inflammatory role by stimulating IL-6 secretion and suppressing TNF-α production in mice.20 In addition, Zhang et al. showed that A2BR activation in human bronchial epithelial cells increases IL-19 secretion which subsequently stimulates TNF-α release by monocytes.24 On the other hand, a number of studies have demonstrated an anti-inflammatory role for A2BR in different settings.9,25,7,26 For example, basal levels of some pro-inflammatory cytokines, like TNF-α, were found to be increased in tissues of A2BR−/− mice,22 and this has been interpreted as an anti-inflammatory role for A2BR. In addition, a recent study by Schingnitz et al. demonstrated a protective role of A2BR signaling in an endotoxin-driven lung injury model which was dependent on pulmonary A2BR signaling.27 These seemingly contradicting studies of A2BR may be due its various signaling partners in different tissues, and whether the signal in the system used originates from bone marrow cells or from tissues. Furthermore, some studies have shown that A2BR may exist in a multi-protein complex in the lung epithelia, and interactions with these partners may explain the different effects.22,28 Endotoxin-induced inflammation is acute, involving a sharp elevation of inflammatory signals and cytokines, which typically involves bone marrow-derived cells. This has proven to be the case also with regard to the contribution of bone marrow cell A2BR to acute inflammation, as we have previously shown.9 This is quite different from pulmonary tissue A2BR signaling, which evokes a milder and likely localized inflammatory profile. Indeed, in our lung IR injury model, tissue-derived rather than bone marrow-derived A2BR signals are involved. Our study leads us to suggest a paradigm according to which the response of A2BR to stress depends whether it is an acute, systemic stress which involves bone marrow cells, or rather localized stress which involves tissue signals. Continued investigations will be required to better understand the pro- and anti-inflammatory roles of A2BR under different settings.

Ventilator-induced injury could account for a significant part of the effects observed in various in vivo lung IR models. However, unlike many of these models in which mice are maintained on ventilation throughout reperfusion, we have reduced the total time of mechanical ventilation to less than 20 min to minimize injury due to ventilation. This was done by extubating the animal during both the 1-hour ischemic and 2-hour reperfusion periods. The minimal lung injury and well-preserved function observed in our sham mice further supports this point. Another limitation of our model is the assessment of lung function with the isolated, buffer-perfused lung system which includes both right and left lungs. As such, total lung function is measured and not just left lung function. However, this is a necessity of the system to prevent unacceptable injury to the left lung as a result of ventilation. In spite of this, we have clearly demonstrated significantly impaired lung function after left hilar clamp versus sham and are confident that the dysfunction measured in our experiments is reflective of left lung injury.

An additional potential limitation of this study is that the expression of other adenosine receptors (A1R, A2AR and A3R) could have been abnormally affected in the A2BR−/− mice after IR. This is unlikely, however, since we have previously shown that A2BR gene deletion does not significantly affect the expression or activity of other adenosine receptor sub-types as evidenced by RT-PCR.9 Thus, the observed effects in the A2BR−/− mice likely cannot be attributed to compensatory changes in expression of other adenosine receptors. We acknowledge that although the expression of any or all adenosine receptors could change after lung IR, this would apply to both wild-type and A2BR−/− mice, which was not a focus of our study.

In summary, pulmonary IR is a complex inflammatory response involving many components. The role of A2BR in this process remains the focus of ongoing investigations. The current study demonstrates a pro-inflammatory role for A2BR in the acute setting of lung IR injury as evidenced by functional parameters, cytokine/chemokine expression and MPO levels. Furthermore, the pro-inflammatory effects of A2BR can be attributed to A2BR activation primarily on resident pulmonary (non-bone marrow-derived) cells such as epithelia. These data suggest that A2BR may provide an additional therapeutic target for prevention or treatment of IR injury in lung transplant recipients. Although previous studies suggest that agonists for other adenosine receptors (A1R, A2AR or A3R) may be therapeutic in the setting of lung IR injury29,30, the present study highlights the importance of maintaining high specificity for these agonists to prevent the activation of A2BR. Because a large amount of extracellular adenosine is known to be produced after IR, it may be optimal to use a combination therapy comprised of an A1R, A2AR or A3R agonist along with an A2BR antagonist. Fortunately, because IR injury is rapidly initiated upon reperfusion and primary graft dysfunction usually occurs within 48 hours, use of adenosine receptor agonists or antagonists to prevent IR injury would likely be required only during the initial 24–48 hours after transplant.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by NIH/NHLBI grants R01 HL092953 (VEL) and T32 HL007849 (ILK).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ailawadi G, Lau CL, Smith PW, Swenson BR, Hennessy SA, Kuhn CJ, et al. Does reperfusion injury still cause significant mortality after lung transplantation? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:688–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christie JD, Edwards LB, Aurora P, Dobbels F, Kirk R, Rahmel AO, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Twenty-sixth Official Adult Lung and Heart-Lung Transplantation Report-2009. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:1031–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schepp CP, Reutershan J. Bench-to-bedside review: adenosine receptors--promising targets in acute lung injury? Crit Care. 2008;12:226. doi: 10.1186/cc6990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cagnina RE, Ramos SI, Marshall MA, Wang G, Frazier CR, Linden J. Adenosine A2B receptors are highly expressed on murine type II alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L467–L474. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90553.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beukers MW, den Dulk H, van Tilburg EW, Brouwer J, Ijzerman AP. Why are A(2B) receptors low-affinity adenosine receptors? Mutation of Asn273 to Tyr increases affinity of human A(2B) receptor for 2-(1-Hexynyl)adenosine. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:1349–1356. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.6.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.St Hilaire C, Koupenova M, Carroll SH, Smith BD, Ravid K. TNF-alpha upregulates the A2B adenosine receptor gene: The role of NAD(P)H oxidase 4. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;375:292–296. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eckle T, Grenz A, Laucher S, Eltzschig HK. A2B adenosine receptor signaling attenuates acute lung injury by enhancing alveolar fluid clearance in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3301–3315. doi: 10.1172/JCI34203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun CX, Zhong H, Mohsenin A, Morschl E, Chunn JL, Molina JG, et al. Role of A2B adenosine receptor signaling in adenosine-dependent pulmonary inflammation and injury. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2173–2182. doi: 10.1172/JCI27303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang D, Zhang Y, Nguyen HG, Koupenova M, Chauhan AK, Makitalo M, et al. The A2B adenosine receptor protects against inflammation and excessive vascular adhesion. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1913–1923. doi: 10.1172/JCI27933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryzhov S, Zaynagetdinov R, Goldstein AE, Novitskiy SV, Dikov MM, Blackburn MR, et al. Effect of A2B adenosine receptor gene ablation on proinflammatory adenosine signaling in mast cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:7212–7220. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma AK, Laubach VE, Ramos SI, Zhao Y, Stukenborg G, Linden J, et al. Adenosine A2A receptor activation on CD4+ T lymphocytes and neutrophils attenuates lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:474–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gazoni LM, Laubach VE, Mulloy DP, Bellizzi A, Unger EB, Linden J, et al. Additive protection against lung ischemia-reperfusion injury by adenosine A2A receptor activation before procurement and during reperfusion. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Z, Sharma AK, Linden J, Kron IL, Laubach VE. CD4+ T lymphocytes mediate acute pulmonary ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:695–702. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Z, Sharma AK, Marshall M, Kron IL, Laubach VE. NADPH oxidase in bone marrow-derived cells mediates pulmonary ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:375–381. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0300OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao M, Fernandez LG, Doctor A, Sharma AK, Zarbock A, Tribble CG, et al. Alveolar macrophage activation is a key initiation signal for acute lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L1018–L1026. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00086.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma AK, Fernandez LG, Awad AS, Kron IL, Laubach VE. Proinflammatory response of alveolar epithelial cells is enhanced by alveolar macrophage-produced TNF-alpha during pulmonary ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L105–L113. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00470.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhong H, Belardinelli L, Maa T, Feoktistov I, Biaggioni I, Zeng D. A(2B) adenosine receptors increase cytokine release by bronchial smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;30:118–125. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0118OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiser SM, Tribble CG, Long SM, Kaza AK, Cope JT, Laubach VE, et al. Lung transplant reperfusion injury involves pulmonary macrophages and circulating leukocytes in a biphasic response. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121:1069–1075. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.113603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross SD, Tribble CG, Gaughen JR, Jr, Shockey KS, Parrino PE, Kron IL. Reduced neutrophil infiltration protects against lung reperfusion injury after transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:1428–1433. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00248-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryzhov S, Zaynagetdinov R, Goldstein AE, Novitskiy SV, Blackburn MR, Biaggioni I, et al. Effect of A2B adenosine receptor gene ablation on adenosine-dependent regulation of proinflammatory cytokines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:694–700. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.131540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolachala V, Ruble B, Vijay-Kumar M, Wang L, Mwangi S, Figler H, et al. Blockade of adenosine A2B receptors ameliorates murine colitis. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:127–137. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolachala VL, Vijay-Kumar M, Dalmasso G, Yang D, Linden J, Wang L, et al. A2B adenosine receptor gene deletion attenuates murine colitis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:861–870. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhong H, Belardinelli L, Maa T, Zeng D. Synergy between A2B adenosine receptors and hypoxia in activating human lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:2–8. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0103OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong H, Wu Y, Belardinelli L, Zeng D. A2B adenosine receptors induce IL-19 from bronchial epithelial cells, resulting in TNF-alpha increase. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:587–592. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0476OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreckler LM, Wan TC, Ge ZD, Auchampach JA. Adenosine inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha release from mouse peritoneal macrophages via A2A and A2B but not the A3 adenosine receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:172–180. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.096016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hart ML, Jacobi B, Schittenhelm J, Henn M, Eltzschig HK. Cutting Edge: A2B Adenosine receptor signaling provides potent protection during intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Immunol. 2009;182:3965–3968. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schingnitz U, Hartmann K, Macmanus CF, Eckle T, Zug S, Colgan SP, et al. Signaling through the A2B adenosine receptor dampens endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. J Immunol. 2010;184:5271–5279. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang P, Lazarowski ER, Tarran R, Milgram SL, Boucher RC, Stutts MJ. Compartmentalized autocrine signaling to cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator at the apical membrane of airway epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14120–14125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241318498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gazoni LM, Walters DM, Unger EB, Linden J, Kron IL, Laubach VE. Activation of A1, A2A, or A3 adenosine receptors attenuates lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010 Apr 17; doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.03.002. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma AK, Linden J, Kron IL, Laubach VE. Protection from pulmonary ischemia-reperfusion injury by adenosine A2A receptor activation. Respiratory Research. 2009;10:58. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]