Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to assess the efficacy of green coffee extract (GCE) as a weight loss supplement, using data from human clinical trials. Electronic and nonelectronic searches were conducted to identify relevant articles, with no restrictions in time or language. Two independent reviewers extracted the data and assessed the methodological quality of included studies. Five eligible trials were identified, and three of these were included. All studies were associated with a high risk of bias. The meta-analytic result reveals a significant difference in body weight in GCE compared with placebo (mean difference: −2.47 kg; 95%CI: −4.23, −0.72). The magnitude of the effect is moderate, and there is significant heterogeneity amongst the studies. It is concluded that the results from these trials are promising, but the studies are all of poor methodological quality. More rigorous trials are needed to assess the usefulness of GCE as a weight loss tool.

1. Introduction

Overweight and obesity have become a serious health concern [1]. Different weight management strategies are presently utilised, and a variety of weight loss supplements sold as “slimming aids” are readily available. However, the efficacy of some of these food supplements remains uncertain. One such supplement is the green coffee extract (GCE).

GCE is present in green or raw coffee [2]. It is also present in roasted coffee, but much of the GCE is destroyed during the roasting process. Some GCE constituents, such as chlorogenic acid (CGA) can also be found in a variety of fruits and vegetables [3]. The daily intake of CGA in persons drinking coffee varies from 0.5 to 1 g [4]. The traditional method of extraction of GCE from green coffee bean, Coffea canephora robusta, involves the use of alcohol as a solvent [5]. Extracted GCE is marketed as a weight loss supplement under a variety of brand names as a weight loss supplement such as “Coffee Slender”, and “Svetol”.

Evidence is accumulating from animal studies regarding the use of GCE as a weight loss supplement [6, 7]. In human subjects, coffee intake has been reported to be inversely associated with weight gain [8]. Consumption of coffee has also been shown to produce changes in several glycaemic markers in older adults [9]. Similarly, other research has indicated that the consumption of caffeinated coffee can lead to some reductions in long-term weight gain, an effect which is likely to be due to the known thermogenic effects of caffeine intake as well as effects of GCE and other pharmacologically active substances present in coffee [10]. GCE has also been postulated to modify hormone secretion and glucose tolerance in humans [11]. This effect is accomplished by facilitating the absorption of glucose from the distal, rather than the proximal part of the gastrointestinal tract.

The objective of this paper is to analyse the results of human clinical trials assessing the efficacy of GCE as a weight-reducing agent.

2. Methods

Electronic searches of the literature were conducted for the following databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED, and The Cochrane Library. Each database was searched from inception up until April, 2010. Search terms used included coffee, green coffee, green coffee extract, roasted coffee, decaffeinated coffee, chlorogenic acid, caffeoylquinic acid, antiobesity agent, appetite suppressant, abdominal fat, BMI, body mass index, body fat, body weight, overweight, over weight, corpulen*, obes*, weight loss, weight decrease, weight watch, weight cycle, weight control, weight gain, weight maintenance, weight reduction, weight change, dietary supplement, food supplement, nutraceutical, nutri*supplement, over-the-counter OR OTC, nonprescription drugs, randomised controlled trial, clinical trial, and placebo. We also searched other internet databases for relevant conference proceedings, as well as our own files. Hand searches of the bibliography of retrieved full texts were also conducted.

Only randomised, double-blind, and placebo-controlled studies were included in this paper. To be considered for inclusion, studies had to test the efficacy of GCE for weight reduction in obese or overweight humans. Included studies also had to report body weight and/or body mass index (BMI) as an outcome. No age, time, or language restrictions were imposed for inclusion of studies. Studies which involved the use of GCE as part of a combination treatment or not involving obese or overweight subjects were excluded from this paper.

Two independent reviewers assessed the eligibility of studies to be included in the paper. Data were extracted systematically by two independent reviewers according to the patient characteristics, interventions, and results. The methodological quality of all included studies was assessed by the use of a quality assessment checklist adapted from the consolidated standard of reporting trials (CONSORT) guidelines [12, 13]. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with the third author.

Data are presented as means with standard deviations. Mean changes in body weight were used as common endpoints to assess the differences between GCE and placebo groups. Using the standard meta-analysis software [14], we calculated mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The I 2 statistic was used to assess for statistical heterogeneity amongst studies.

3. Results

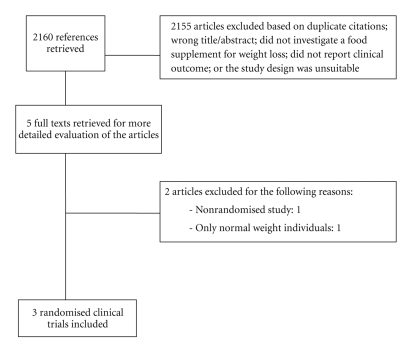

Our searches produced 2160 “hits”. 328 articles were excluded because they were duplicate citations, while 767 articles were excluded because of wrong titles and abstracts. Another 598 articles were excluded because they did not investigate a food supplements, and 454 articles excluded due to no report on clinical outcome. A further 13 articles were excluded due to unsuitable study design. Thus, 5 potentially relevant articles were identified (Figure 1). One trial was excluded because it involved only normal weight individuals, and did not measure weight as an outcome [15]. Another trial was excluded because it was not randomised [16]. In effect, 3 randomised clinical trials (RCTs) including a total of 142 participants met our inclusion criteria, and were included in this systematic paper [5, 17, 18]. Their key details are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for inclusion of randomised clinical trials.

Table 1.

Methodological characteristics of included studies.

| Author Year Country | Main outcome (s) | Main diagnoses of study participants | Study design | Gender M/F | Randomisation appropriate? | Allocation concealed? | Groups similar at baseline? | Similar follow-up of groups? | Outcome assessor blinded? | Care provider blinded? | Patients blinded? | Attrition bias? | ITT analysis? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Ayton Research 2009 United Kingdom | Body weight, waist, bust and hip circumference | Healthy overweight subjects | Parallel | Unclear | ? | ? | + | + | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Thom 2007 Norway | Body weight, body mass index | Slight to moderately overweight subjects | Parallel | 12/18 | ? | ? | + | + | ? | ? | ? | − | − |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Dellalibera 1998 France | Body weight, body mass index | Overweight volunteers | Parallel | Unclear | ? | ? | + | + | ? | ? | ? | − | − |

Abbreviation: ITT (intention-to-treat); M/F: Males/Females.

Symbols: *: Unpublished study, +: Yes, −: No, ?: Unclear.

Table 2.

Main results of included RCTs1.

| Author Year | GCE specification | No. of participants randomised | Age in yrs; Sex: M/F | Body weight at baseline | Dosage of GCE | Treatment duration | Main results; reported as means with standard deviations | Adverse events | Control for lifestyle factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayton Res. 2009 (unpublished) | CGA enriched green coffee | 62 | Not reported | 76.65 ± 7.25 kg (GCE) 77.44 ± 12.93 kg (PLA) | 180 mg daily | 4 weeks | Weight loss was 1.35 ± 0.81 kg and 0.12 ± 0.27 kg for GCE and PLA respectively | Not reported | Normal lifestyle |

|

| |||||||||

| Thom 2007 | CGA enriched green coffee | 30 | Not reported 12/18 | 85.2 ± 4.5 kg (GCE) 84.3 ± 4.3 kg (PLA) | 200 mg daily | 12 weeks | Mean weight loss was 5.4 ± 0.6 kg (GCE) and 1.7 ± 0.9 kg (PLA). Mean fat loss was 3.6 ± 0.3% (GCE) and 0.7 ± 0.4% (PLA) | No adverse events | Regular diet, normal level of exercise |

|

| |||||||||

| Dellalibera 2007 | Green coffee extract | 50 | Range: 19–75 | Not reported | 200 mg daily | 12 weeks | 2 Mean weight loss was 4.97 ± 0.32 kg and 2.45 ± 0.37 kg for GCE and PLA, respectively | Not reported | Not reported |

Abbreviation: PLA: placebo

1 Unless otherwise specified, values are reported as means with standard deviations.

2 Values reported as means with standard errors.

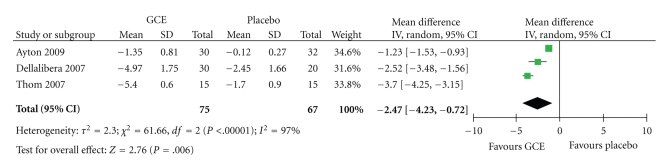

A forest plot (random-effect model) for the three trials is shown in figure 2. The meta-analysis reveals a statistically significant difference in body weight between GCE and placebo (MD: −2.47 kg; 95% CI: −4.23, −0.72). The I 2 statistic of 97% suggests that there is considerable heterogeneity amongst the studies. A further plot of two trials which involved CGA-enriched GCE revealed a statistically nonsignificant difference in body weight between GCE and placebo (MD: −1.92 kg; 95% CI: −5.40, 1.56). Heterogeneity was also considerable in this analysis (I 2 statistic of 99%). One of the studies reported a statistically significant decrease in the percentage of body fat in the GCE group compared with baseline, but no significant difference in the placebo group [5]. There was no mention of intergroup differences regarding the percentage of body fat. None of the trials reported any adverse events associated with the use of GCE.

4. Discussion

The main purpose of this systematic paper was to assess the efficacy of GCE as a weight loss supplement. The overall meta-analysis revealed a significant difference in change in body weight between GCE and placebo. The magnitude of this significance is moderate, and the clinical relevance is therefore not certain. There is also considerable heterogeneity amongst the three trials.

In animals, GCE has been reported to influence postprandrial glucose concentration and blood lipid concentration [5]. This is thought to be via reduction in the absorption of glucose in the intestine; a mechanism achieved by promoting dispersal of the Na+ electrochemical gradient. This dispersal leads to an influx of glucose into the enterocytes [19]. GCE is also thought to inhibit the enzymatic activity of hepatic glucose-6-phosphatase, which is involved in the homeostasis of glucose [20]. Reports from animal studies have suggested that GCE mediates its antiobesity effect possibly by suppressing the accumulation of hepatic triglycerides [6]. Some authors have also posited that the antiobesity effect of GCE may be mediated via alteration of plasma adipokine level and body fat distribution and downregulating fatty acid and cholesterol biosynthesis, whereas upregulating fatty acid oxidation and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) expression in the liver [7].

Diets rich in polyphenols may help to prevent various kinds of diseases associated with oxidative stress, including coronary heart disease and some forms of cancer [21, 22]. GCE has been reported to have antioxidant activity, demonstrated by its ability to scavenge free radicals in vitro, and to increase the antioxidant capacity of plasma in vivo [16, 23]. There is also evidence that certain dietary phenols, including GCE, may modify intestinal glucose uptake in a number of ways [8, 24]. This activity might provide a basis for explaining its effects on body weight. The purported slimming effect of GCE would have a protective effect against diabetes mellitus, via changes in gastrointestinal hormone secretion [10]. A few questions, however, arise from the RCTs which involve the use of GCE as a weight loss aid.

All the RCTs involving the use of GCE which have been conducted so far have very small sample sizes, with the largest number of participants being 62 in one trial [17]. These small sample sizes increase the possibility of spurious or false positive results. Two of the RCTs were unclear about drop-outs of participants from the trial; neither did they report on intention-to-treat analysis [17, 18]. All of the trials so far identified have been of very short duration. This makes it difficult to assess the efficacy and safety of GCE as a weight reduction agent on the medium to long-term. Although none of the RCTs identified reported any adverse events, this does not indicate that GCE intake is “risk-free”. Two participants in a study report dropped out due to adverse events associated with the intake of GCE [16]. These included headache and urinary tract infection. Thus, the safety of this weight loss aid is not established.

The effective dosage of GCE for use as a weight loss supplement is also not established. The dosages of GCE reported in most of the human trials identified were estimated, as the GCE was a component of coffee. While 2 of the RCTs identified enriched their GCE with CGA [5, 17], the third trial did not report that the GCE used was fortified with CGA [18]. This warrants further investigation.

The RCTs identified from our searches were not also clear on blinding issues. None of the RCTs reported on how randomisation was carried out, and none provided information regarding blinding of outcome assessors. This casts doubt on the internal validity of these trials. Future trials involving the use of GCE as a weight loss supplement should be conducted in line with the CONSORT guidelines. This will ensure the validity and applicability of study results. Two authors in one study were affiliated to a company which markets Svetol [18] but did not specify whether or not they had any conflicts of interest.

This systematic review has several limitations. Though our search strategy involved both electronic and nonelectronic studies, we may not have identified all the available trials involving the use of GCE as a weight loss supplement. Furthermore, the methodological quality of the studies identified from our searches is poor, and all are of short duration. These factors prevent us from drawing firm conclusions about the effects of GCE on body weight.

5. Conclusion

The evidence from RCTs seems to indicate that the intake of GCE can promote weight loss. However, several caveats exist. The size of the effect is small, and the clinical relevance of this effect is uncertain. More rigorous trials with longer duration are needed to assess the efficacy and safety of GCE as a weight loss supplement.

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the effect of GCE on body weight.

Conflict of Interests

I. Onakpoya is funded by a grant from GlaxoSmithKline. The funder had no role in the preparation of the paper. R. Terry and E. Ernst declare no potential conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Yanovski SZ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. The epidemiology of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(6):2087–2102. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farah A, Monteiro M, Donangelo CM, Lafay S. Chlorogenic acids from green coffee extract are highly bioavailable in humans. Journal of Nutrition. 2008;138(12):2309–2315. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.095554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Rémésy C, Jiménez L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;79(5):727–747. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clifford MN. Chlorogenic acids and other cinnamates: nature, occurrence, dietary burden, absorption and metabolism. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2000;80(7):1033–1043. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thom E. The effect of chlorogenic acid enriched coffee on glucose absorption in healthy volunteers and its effect on body mass when used long-term in overweight and obese people. Journal of International Medical Research. 2007;35(6):900–908. doi: 10.1177/147323000703500620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimoda H, Seki E, Aitani M. Inhibitory effect of green coffee bean extract on fat accumulation and body weight gain in mice. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2006;6, article 9 doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho A-S, Jeon S-M, Kim M-J, et al. Chlorogenic acid exhibits anti-obesity property and improves lipid metabolism in high-fat diet-induced-obese mice. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2010;48(3):937–943. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez-Garcia E, Van Dam RM, Rajpathak S, Willett WC, Manson JE, Hu FB. Changes in caffeine intake and long-term weight change in men and women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;83(3):674–680. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.83.3.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiltunen LA. Are there associations between coffee consumption and glucose tolerance in elderly subjects? European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;60(10):1222–1225. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg JA, Boozer CN, Geliebter A. Coffee, diabetes, and weight control. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;84(4):682–693. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.4.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnston KL, Clifford MN, Morgan LM. Coffee acutely modifies gastrointestinal hormone secretion and glucose tolerance in humans: glycemic effects of chlorogenic acid and caffeine. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003;78(4):728–733. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, Lepage L. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. The Lancet. 2001;357(9263):1191–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, et al. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;134(8):663–694. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer Program] Version 5.0. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

- 15.Watanabe T, Arai Y, Mitsui Y, et al. The blood pressure-lowering effect and safety of chlorogenic acid from green coffee bean extract in essential hypertension. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension. 2006;28(5):439–449. doi: 10.1080/10641960600798655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blum J, Lemaire B, Lafay S, et al. Effect of a green decaffeinated coffee extract on glycemia: a pilot prospective clinical study. Nutrafoods. 2007;6(3):13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayton Global Research. Independent market study on the effect of coffee shape on weight loss—the effect of chlorogenic acid enriched coffee (coffee chape) on weight when used in overweight people. June 2009, http://www.coffeshape.eu/independent/.

- 18.Dellalibera O, Lemaire B, Lafay S. Svetol®, green coffee extract, induces weight loss and increases the lean to fat mass ratio in volunteers with overweight problem. Phytotherapie. 2006;4(4):194–197. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welsch CA, Lachance PA, Wasserman BP. Dietary phenolic compounds: inhibition of Na+-dependent D-glucose uptake in rat intestinal brush border membrane vesicles. Journal of Nutrition. 1989;119(11):1698–1704. doi: 10.1093/jn/119.11.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hemmerle H, Burger H-J, Below P, et al. Chlorogenic acid and synthetic chlorogenic acid derivatives: novel inhibitors of hepatic glucose-6-phosphate translocase. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1997;40(2):137–145. doi: 10.1021/jm9607360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tijburg LBM, Mattern T, Folts JD, Weisgerber UM, Katan MB. Tea flavonoids and cardiovascular diseases: a review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 1997;37(8):771–785. doi: 10.1080/10408399709527802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adlercreutz H, Mazur W. Phyto-oestrogens and Western diseases. Annals of Medicine. 1997;29(2):95–120. doi: 10.3109/07853899709113696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monteiro M, Farah A, Perrone D, Trugo LC, Donangelo C. Chlorogenic acid compounds from coffee are differentially absorbed and metabolized in humans. Journal of Nutrition. 2007;137(10):2196–2201. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.10.2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bidel S, Hu G, Sundvall J, Kaprio J, Tuomilehto J. Effects of coffee consumption on glucose tolerance, serum glucose and insulin levels: a cross-sectional analysis. Hormone and Metabolic Research. 2006;38(1):38–43. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]