Abstract

4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and N′-nitrosonornicotine (NNN) are tobacco-specific nitrosamines present in tobacco products and smoke. Both compounds are carcinogenic in laboratory animals, generating tumors at sites comparable to those observed in smokers. These Group 1 human carcinogens are metabolized to reactive intermediates that alkylate DNA. This paper focuses on the DNA pyridyloxobutylation pathway which is common to both compounds. This DNA route generates 7-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl]-2′-deoxyguanosine, O 2-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl]-2′-deoxycytosine, O 2-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl]-2′-deoxythymidine, and O 6-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl]-2′-deoxyguanosine as well as unstable adducts which dealkylate to release 4-hydroxy-1-{3-pyridyl)-1-butanone or depyriminidate/depurinate to generate abasic sites. There are multiple repair pathways responsible for protecting against the genotoxic effects of these adducts, including adduct reversal as well as base and nucleotide excision repair pathways. Data indicate that several DNA adducts contribute to the overall mutagenic properties of pyridyloxobutylating agents. Which adducts contribute to the carcinogenic properties of this pathway are likely to depend on the biochemistry of the target tissue.

1. Introduction

Tobacco use has been linked to a variety of human cancers, including lung, oral cavity, esophagus, pharynx, larynx, urinary bladder, pancreas, and liver cancers [1]. Lung cancer alone is responsible for the deaths of 1.3 million people annually worldwide [2]. It is the leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States, with 80%–90% of this cancer associated with tobacco use [1]. Environmental tobacco smoke (second-hand smoke) has also been associated with human lung cancer but the risks are significantly lower than those associated with smoking [1].

There are more than 5000 identified chemicals present in cigarette smoke [1, 3–5]. More than 60 of these compounds are demonstrated chemical carcinogens in animal models [1, 3, 4, 6]. An important group of tobacco carcinogens are the tobacco-specific nitrosamines. These compounds are formed from tobacco alkaloids like nicotine during the curing process of tobacco [7]. 4(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and N′-nitrosonornicotine (NNN) are two of the most potent tobacco-specific nitrosamines present in tobacco products and smoke [8]. Both compounds are carcinogenic in laboratory animals, generating tumors at sites comparable to those observed in smokers [8]. NNK is a potent lung carcinogen, which also induces liver and nasal tumors [9–11]. This compound induces lung adenocarcinomas in rodents at lifetime doses that are comparable to those experienced by smokers [8]. Adenocarcinoma is now the most common type of lung cancer observed in humans, having surpassed squamous cell carcinoma [12–16]. This shift in histology has been attributed not to improvements in diagnoses but rather to changing cigarette design, which has changed smoking behavior resulting in increased uptake of tobacco-specific nitrosamines by smokers [14]. Metabolic products of NNK have been detected in urine of smokers and individuals exposed to second-hand smoke, indicating that humans are exposed to and metabolize this carcinogen [17–20]. NNN is carcinogenic to the esophagus, nasal cavity, and respiratory tract in laboratory animals [8]. This nitrosamine is present in higher amounts than any other esophageal carcinogen in tobacco smoke [8]. It and/or its glucuronide conjugate have been detected in the urine and toenails of smokers and smokeless tobacco users [21–25]. Based on animal studies, NNK and NNN are listed as Group 1 human carcinogens by the International Agency for Cancer Research [6, 8].

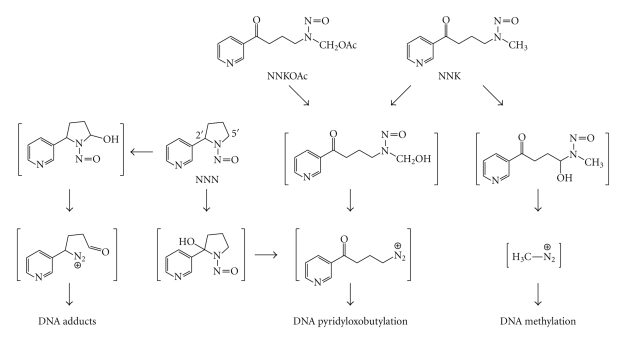

NNK and NNN require metabolism to exert their toxicological properties [8]. NNK-induced carcinogenesis requires cytochrome P450 catalyzed metabolic activation to DNA reactive metabolites [26]. NNK is metabolized to either a methylating or a pyridyloxobutylating agent (Scheme 1). The methylation pathway generates well-characterized methyl DNA adducts, such as 7-methylguanine (7-mG), O 6-methylguanine (O 6-mG), and O 4-methylthymidine (O 4-mT) [27–31]. The dominant mutagenic adduct is O 6-mG [32, 33]. The repair mechanisms and genotoxic properties of this adduct have been extensively reviewed [34–37] and will not be a focus of this paper. The formation, repair, and genotoxic properties of the pyridyloxobutyl adducts will be discussed below.

Scheme 1.

Pathways of bioactivation of NNK, NNN, and model pyridyloxobutylating agent, NNKOAc.

NNN also has two pathways to form DNA adducts, 2′- and 5′-hydroxylation [8]. (S)-NNN, the dominant enantiomer in tobacco products [38], undergoes primarily 2′-hydroxylation whereas (R)-NNN undergoes both 2′- and 5′-hydroxylation [39]. 2′-Hydroxylation generates the same pyridyloxobutylating agent as methyl hydroxylation of NNK (Scheme 1). 5′-Hydroxylation generates a reactive metabolite that can also alkylate DNA (Scheme 1) [40, 41]. However, no data exist for the levels of these adducts in vivo. For the purpose of this paper, we will focus on the pyridyloxobutylation pathway.

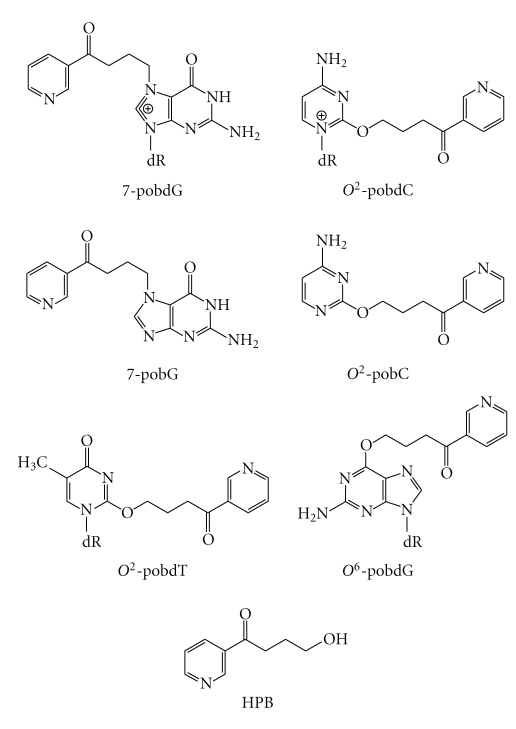

2. Structure of Pyridyloxobutyl DNA Adducts

The pyridyloxobutylation pathway leads to a variety of adducts, four of which have been recently identified (Scheme 2). They are 7-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl]-2′-deoxyguanosine (7-pobdG) [42], O 2-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl]-2′-deoxycytosine (O 2-pobdC) [43], O 2-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl]-2′-deoxythymidine (O 2-pobdT) [43], and O 6-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl]-2′-deoxyguanosine (O 6-pobdG) [42–44]. Both 7-pobdG and O 2-pobdC readily release the corresponding nucleobases, 7[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl]-guanine (7-pobG) and O 2-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl]-cytosine (O 2-pobC), respectively, leaving behind an abasic site [42, 43]. In addition, some pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts are unstable and dealkylate to release 4-hydroxy-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (HPB) (Scheme 2) [31, 45]. HPB-releasing adducts include O 2-pobdC [43] and 7-pobdG [42]. Quantitation of the specific pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts in calf thymus DNA treated with a model pyridyloxobutylating agent, 4-(acetoxymethylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNKOAc, Scheme 1), demonstrates that HPB-releasing adducts are the major adducts present in pyridyloxobutylated DNA [46]. They represent approximately 65% of the total adducts formed. The relative levels of the specific adducts making up the remainder are 7-pobG > O 6-pobdG>O 2-pobdT ≥ O 2-pobC.

Scheme 2.

Structures of pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts and HPB.

Conflicting evidence exists for the formation of phosphate adducts in pyridyloxobutylated DNA. HPB is not released from pyridyloxobutylated DNA when heated under basic conditions [45]. This observation is not consistent with the presence of pyridyloxobutyl phosphate esters. However, the 3′-termini of NNKOAc-induced strand breaks are resistant to 32P-endlabeling in the presence of T4 DNA polymerase even after incubating with endonuclease IV which removes 3′-phosphate or 3′-phosphoglycolate groups [47]. This observation suggests that there may be an adduct on the 3′-phosphate group. However, the nucleobase adduct, O 6-pobdG, has been reported to inhibit 3′-exonuclease degradation of DNA [48]. Therefore, it is possible this adduct or other pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts inhibits endonuclease IV as well. Also supporting the formation of pyridyloxobutyl phosphate adducts is the detection of a 4-(3-[5-3H]pyridyl)-4-hydroxy-2-butylcobalam complex when enzymatic digests of DNA from [5-3H]NNK-treated animals were reacted with cob(I)alamin followed by sodium borohydride [49]. This reaction product accounted for up to 22% of the total pyridyloxobutyl adducts detected. Cob(I)alamin selectively reacts with alkyl phosphate adducts [50]. However, the pyridyloxobutyl group might be more reactive with this reagent than a simple alkyl group and the product may be formed from adducts other than alkyl phosphates. This possibility requires further testing.

3. Levels of Pyridyloxobutyl DNA Adducts in NNK- or NNN-Treated Rodents

Pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts have been observed in DNA isolated from the tissues of NNK- or NNN-treated animals. HPB-releasing adducts have been detected in target tissues and have been shown to persist [8, 52]. They have also been linked to tumor formation in the rat [53]. More recent studies have reported the levels of specific adducts in target and nontarget tissues of NNK- or NNN-treated rodents. One of the first studies demonstrated that O 6-pobdG was present at very low levels in lung and liver DNA from [5-3H]NNK-treated A/J mice [54]. Subsequent experiments have employed sensitive LC-MS/MS assays [55, 56] for their detection of DNA from in vivo sources. Table 1 displays the levels of pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts detected in lung and liver DNA following four subcutaneous doses of NNK [51]. In this study, the relative adduct distribution was O 2-pobdT ≥ 7-pobG > O 2-pobC ≫ O 6-pobdG in lung DNA and O 2-pobdT = 7-pobG ≥ O 2-pobC ≫ O 6-pobdG in liver DNA. The levels of 7-pobG, O 2-pobC and O 2-pobdT were higher in liver relative to lung DNA wherease the levels of O 6-pobdG were higher in lung relative to liver. O 2-pobdT was also the dominant adduct detected when rats were chronically treated with a lower dose of NNK (10 ppm in drinking water) (Table 2) [57, 58]. The relative distribution of pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts was O 2-pobdT > 7-pobG ≫ O 2-pobC ≫ O 6-pobdG in lung DNA and O 2-pobdT ≫ 7-pobG > O 2-pobC in liver DNA; O 6-pobdG was not observed in liver DNA from these animals [57]. Pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts were also observed in nasal respiratory mucosa, nasal olfactory mucosa, oral mucosa, and pancreas from NNK-treated rats [59]. The relative levels of total pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts is lung > liver > nasal respiratory mucosa > nasal olfactory mucosa ≈ oral mucosa ≈ pancreas [59].

Table 1.

Adduct levels in NNK-treated rats [51].

| Tissue | NNK Dose (mmol/kg)a | 7-pobG | O 2-pobdT | O 2-pobC | O 6-pobG |

| Mean ± S.D., N = 5 (fmol/mg DNA) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Lung | saline control | N.D.b | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 0.025 | 933 ± 89 | 1120 ± 66 | 483 ± 36 | 251 ± 26 | |

| 0.1 | 1800 ± 478 | 2020 ± 483 | 840 ± 169 | 487 ± 101 | |

|

| |||||

| Liver | saline control | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 0.025 | 3550 ± 1600 | 3530 ± 725 | 2930 ± 521 | 28 ± 17 | |

| 0.1 | 12200 ± 1600 | 12300 ± 1690 | 7800 ± 1680 | 140 ± 25 | |

aAdministered by s.c. injection daily for 4 days.

bN.D.: not detected (detection limit, 3 fmol/mg DNA).

Table 2.

Comparative DNA adduct levels in lung and liver of F344 rats treated with 10 ppm NNK in the drinking water and sacrificed at various intervals [57, 58].

| Adduct Levels fmol/mg DNA (mean ± S.D.) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | Week | 1 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 16 | 20 |

| O 6 -mG | 976 ± 342 | 1020 ± 423 | 2550 ± 263 | 1020 ± 314 | 729 ± 57.5 | 1910 ± 615 | |

| O 6-pobdG | 45 ± 7a | 50 ± 5a | 46 ± 13a | 44 ± 14a | 34 ± 17a | 20 ± 5a | |

| 7-pobG | 750 ± 95 | 1180 ± 131 | 1360 ± 214a | 2220 ± 864 | 1700 ± 175a | 1060 ± 169 | |

| O 2 -pobdT | 1080 ± 99 | 2020 ± 150 | 3890 ± 648 | 8260 ± 2730a | 6720 ± 606a | 5070 ± 1060a | |

| O 2-pobC | 240 ± 23 | 250 ± 18 | 400 ± 87a | 730 ± 211 | 810 ± 152 | 940 ± 175 | |

|

| |||||||

| Liver | Week | 1 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 16 | 20 |

| O 6 -mG | 3830 ± 865 | 7120 ± 2080 | 2310 ± 946 | 564 ± 250 | 637 ± 59 | 891 ± 379 | |

| O 6-pobdG | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| 7-pobG | 490 ± 104a | 880 ± 182a | 1050 ± 90 | 1460 ± 625 | 1170 ± 86a | 730 ± 225 | |

| O 2-pobdT | 650 ± 121a | 1230 ± 272a | 2190 ± 174 | 3740 ± 1170a | 3540 ± 643a | 2680 ± 643a | |

| O 2-pobC | 170 ± 43a | 140 ± 25a | 240 ± 17 | 580 ± 214 | 350 ± 152 | 490 ± 146 | |

n.d., not detected.

aSignificantly different from O 6-mG, P < .05.

Similar studies have been performed in NNN-treated rats [60, 61]. Chronic treatment of F344 rats with (R)-NNN or (S)-NNN in the drinking water (10 ppm, 1–20 weeks) led to adduct formation in lungs, liver, nasal respiratory mucosa, nasal olfactory, and oral mucosa [60, 61]. Target tissues (nasal olfactory, respiratory mucosa, and esophagus) had the highest levels of pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts whereas the nontarget tissues (lung and liver) had the lowest levels. The enantiomers gave different levels of pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts in the various tissues. (R)-NNN produced the highest levels in lung nasal olfactory and nasal repiratory tissue whereas (S)-NNN generated higher levels in esophagus, liver, and oral mucosa [60, 61]. These tissue-dependent differences are likely due to tissue differences in the cytochrome P450 enzymes responsible for the bioactivation of these two enantiomers [60, 61].

As with NNK, O 2-pobdT was a major adduct observed in DNA from various NNN-exposed tissues such as nasal ofactory mucosa (O 2-pobdT > 7-pobG ≫ O 2-pobC > O 6-pobdG), respiratory mucosa (O 2-pobdT > 7-pobG ≫ O 2-pobC > O 6-pobdG), and oral mucosa (O 2-pobdT ≈ 7-pobG ≫ O 2-pobC > O 6-pobdG) as well as liver and lung (O 2-pobdT ≫ 7-pobG ≥ O 2-pobC). In the rat esophagus, 7-pobG was the dominant adduct (7-pobG ≥ O 2-pobdT ≈ O 2-pobC). O 6-pobdG was not detected in lung, liver or esophageal DNA [60].

4. Formation of Pyridyloxobutyl DNA Adducts in Humans

While there is no information regarding the levels of the four individual pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts in humans, HPB-releasing adducts have been detected in human tissue samples. Levels of these adducts were significantly higher (P < .0001) in self-reported smokers who had lung cancer than in self-reported nonsmokers who had lung cancer (404 ± 258 versus 59 ± 56 fmol HPB released/mg DNA, resp.) [62]. Since HPB-releasing adducts accumulate in normal lung tissues of lung cancer patients but not in normal smoking controls [62, 63], these data support a hypothesis that smokers who accumulate pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts may be at increased risk of lung cancer.

5. Repair Pathways for Pyridyloxobutyl DNA Adducts

DNA adduct repair protects a cell against the toxic and genotoxic effects of DNA damage. There are multiple pathways involved in the removal of alkylated DNA bases generated by reactive alkanediazohydroxides. These include direct base repair by alkyltransferases and excision of the DNA damage by base excision repair (BER) or nucleotide excision repair (NER). Mismatch repair is involved in the detection and repair of mismatched DNA adducts. Below is a review of the pathways thought to be involved in the repair of pyridyloxobutyl DNA damage.

5.1. Adduct Reversal

O 6-Alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase (AGT) is a suicide protein that repairs O 6-alkylguanine adducts by facilitating the transfer of the alkyl group from the O 6-position of guanine to a cysteine residue in the protein's active site [35]. This alkylation reaction inactivates the protein and triggers a conformational change [64] which leads to its degradation [65]. Consequently, the initial repair capacity of a cell is determined by its constitutive levels of AGT.

While O 6-pobdG is readily repaired by mammalian AGTs, it is not a good substrate for the bacterial AGTs ada and ogt [66]. The ability of AGT orthologs to repair this bulky O 6-alkylguanine adduct is likely determined by the size of the protein's adduct binding site. Rodent AGT has the largest binding site and repairs O 6-pobdG faster than human AGT which has a smaller binding pocket [66]. The bacterial AGTs have an even smaller binding pocket, explaining the inability of these proteins to repair this damage [66]. This adduct reversal pathway is a major repair pathway for O 6-pobdG in mammalian cells [54, 66, 67].

5.2. Base Excision Repair

Base excision repair (BER) is another important pathway for the repair of nitrosamine-derived DNA damage. This pathway is involved in the repair of single strand breaks, small alkyl guanine damage, and oxidized DNA bases as well as abasic sites [68, 69]. It is a multistep process that is initiated when damaged bases are removed by glycosylases, leaving abasic sites in DNA. The abasic sites are removed by an endonuclease. The missing nucleoside is then replaced and ligation occurs. It is likely that NNK-derived methyl adducts such as 7-methylguanine and N 3-methyladenine are removed by base excision repair [70]. The ability of pyridyloxobutyl adducts to serve as substrates for BER glycosylases has not been studied. It is possible that they could serve as substrates since the structurally similar adduct, O 6-butylguanine, appears to be repaired in part by BER in vivo [71]. It is likely that abasic sites formed by the depurination/depyrimidination of 7-pobG and O 2-pobC, respectively, are repaired by this pathway.

While little is known about the role of BER in the repair of pyridyloxobutyl DNA damage, two observations suggest that BER may be important. First, incubation of lysate from NNKOAc-treated cells with formamidopyrimidine glycosylase prior to the COMET assay results in a small but significant increase in strand breaks [72]. This observation indicates that there are pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts that are substrates for this glycosylase. Second, loss of XRCC1, an important scaffold protein in BER [73], increases the mutagenic and toxic effects of NNKOAc [67]. The loss of this protein does not affect the rate of removal of specific pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts from DNA [67]. However, the observed increase in toxicity and mutagenicity indicates that XRCC1 plays an important role in protecting a cell against the harmful effects of these adducts. Together, these observations provide evidence for the role of BER in the repair of pyridyloxobutyl DNA damage.

5.3. Nucleotide Excision Repair

Another important pathway for the repair of bulky DNA damage is nucleotide excision repair (NER) [74, 75]. Like BER, NER is a multiprotein mediated repair pathway. However, in this pathway a whole section of the damaged DNA strand is removed in several steps. A new strand is then synthesized by DNA polymerase using the undamaged strand as a template.

Several pieces of experimental data support the importance of NER in the repair of pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts. In one study, [α-32P]TTP was incorporated into NNKOAc-treated plasmid DNA when incubated with extracts from normal human lymphoid cells in an ATP-dependent fashion [76]. This activity was significantly lower in cell extracts from XPA- and XPC-deficient cell lines. XPA and XPC are two important proteins involved in the initiation of the NER pathway [74, 75] so their absence significantly impacts the efficiency of NER.

A second study examined the removal of specific pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts from DNA in NNKOAc-treated Chinese hamster ovary cells [67]. The rate of removal of these adducts was compared between the parental cell line, AA8, which has functional NER but not AGT, and UV5 cells which lacks both functional NER [loss of ERCC-2 (XPD)] and AGT [77]. O 2-pobdT was the only adduct whose removal was affected by the loss of ERCC-2. Its repair was significantly slower in the absence of this protein, suggesting the importance of NER in the removal of this adduct. Since there were several reports indicating that larger O 6-alkylguanine adducts appear to be preferentially repaired by nucleotide excision repair [78–82], O 6-pobdG repair was also expected to be reduced in cells lacking NER. However, O 6-pobdG was a poor substrate for this pathway in CHO cells as well as in an in vitro human NER repair assay [67].

5.4. Mismatch Repair

Mismatch repair (MMR) is another important guard against genotoxic stress. In the case of alkylating agents, this pathway plays a critical role in the cytotoxicity mediated by these compounds [70, 83–85]. When alkylation is extensive, MMR is involved in triggering cell death which protects against the mutagenic activity of these agents. For example, MMR recognizes O 6-mG-T mismatch that occur when AGT is overwhelmed [83]. Unrepaired O 6-mG is toxic [36]; absence of MMR removes the toxicity of methylating agents indicating that this repair pathway is involved in the mechanism of toxicity [34]. MMR is initiated when the MSH2-MSH6 heterodimer (MutSα) binds to the mismatch. The MLH1-PMS2 heterodimer then binds to MutSα and triggers removal of the mismatched base. In the case of damaged bases, the mismatch process enters a futile cycle if the adduct is not repaired since polymerases repeatedly insert the wrong base opposite the modified base. This futile cycle can trigger apoptosis [70, 85]. This futile cycle can be thwarted by homologous recombination, a multiprotein pathway that uses the sister chromatid as the template to circumvent replication-halting DNA adducts [85, 86].

The role of mismatch repair in a cell's response to pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts has not been explored. Preliminary data indicate that O 6-pobdG may not be a very toxic adduct. Repair of O 6-pobdG by human AGT in bacteria did not influence the toxicity of the model pyridyloxobutylating agent, NNKOAc [87]. This observation differs starkly from that observed with methylating agents where the toxicity of a methylating agent is markedly reduced when AGT is expressed [87]. Similar results were observed in CHO cells; AGT expression only minimally reduced the cytotoxicity of NNKOAc while repairing almost 100% of the O 6-pobdG formed by this pyridyloxobutylating agent [67]. The reduced toxicity of O 6-pobdG may cause it to more greatly contribute to the overall mutagenic activity of a pyridyloxobutylating agent since cell death protects against the mutagenic activity of DNA alkylating agents.

5.5. In Vivo Repair

For both NNK and NNN, the relative distribution of the four pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts in tissues from exposed rats was significantly different from that observed in DNA treated with a model pyridyloxobutylating agent in vitro [56, 57, 59–61]. This difference likely results from the active repair of specific adducts. Further support for this hypothesis is the observed tissue variation in relative adduct distribution [57, 59–61].

One adduct that appears to be well-repaired in vivo is O 6-pobdG [56, 57, 59–61]. The levels of this adduct are very low relative to the other adducts (Tables 1 and 2). In NNK-treated animals, the levels of O 6-mG were much greater than the levels of O 6-pobdG and in the range of the other pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts [58]. This observation suggests that the larger adduct, O 6-pobdG, is more readily repaired than O 6mG in vivo. AGT is one pathway clearly responsible for the repair of O 6-pobdG in vivo [54]. However, other repair pathways may also be involved since this adduct does not accumulate in lungs of AGT knockout mice whereas O 6-mG does (Table 3) [88]. This conclusion is further supported by data in wild-type mice which indicates that AGT is inactivated in mouse lung following exposure to NNK [89].

Table 3.

Levels of O 6-mG and O 6-pobG in lung and livers of NNK-treated wild-type and AGT knockout micea [88].

| pmol adducts/μmol guanine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGT status | lung | liver | ||

|

| ||||

| O 6-mG | 24 h | 4 weeks | 24 h | 4 weeks |

| Wildtype | 42 ± 12 | 55 ± 9 | 17 ± 11 | 5.3 ± 0.7 |

| Knockout | 65 ± 19 | 110 ± 20 | 210 ± 110 | 380 ± 80b |

|

| ||||

| O 6-pobG | ||||

| Wildtype | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | ≤0.3 |

| Knockout | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 1.2 | 4.9 ± 1.4 |

aMice received either a single dose of NNK (~250 mg/kg) and sacrificed 24 h postinjection or three weekly doses of NNK (~250 mg/kg each week) and sacrificed 1 week after the third treatment. Numbers represent the average of five samples ± SD.

bThree samples ± SD. Two other samples were analyzed and these two animals had O 6-mG levels of 26 and 31 pmol O 6-mG/μmol guanine. The liver 7-mG adduct levels for all five animals were similar: 134 ± 17 pmol 7-mG/μmol guanine.

The most persistent adduct in vivo is O 2-pobdT [56, 57, 59–61]. This adduct is a minor adduct in the absence of repair (7-pobG > O 6-pobdG > O 2-pobdT ≥ O 2-pobC) [46]. This is somewhat surprising since this adduct is repaired by NER in cell line models [67]. A recent study indicated that NER is reduced in the lungs of NNK-treated mice providing an explanation for the persistence of this adduct in vivo [90]. The mechanism of this reduction is unknown.

6. Mutagenic Activity of Pyridyloxobutyl DNA Adducts

Pyridyloxobutylating agents are mutagenic in a variety of test systems [67, 87, 91, 92]. However, our knowledge of which pyridyloxobutyl adducts are causing mutations is still rudimentary. Site-specific mutagenesis studies have only been performed for one adduct, O 6-pobdG [93]. In bacteria, it produces exclusively GC to AT transitional mutations. In human kidney cell line 293 cells, it produces primarily GC to AT transitional mutations with some GC to TA transversions and deletions as well as a number of more complex mutations.

A few studies have begun to link the overall mutagenic activity of pyridyloxobutyl DNA damage to specific adducts through exploring the impact of various DNA repair pathways on the mutagenic properties of the model pyridyloxobutylating agent, NNKOAc. The earliest studies were performed in bacteria. NNKOAc is mutagenic in Salmonella typhimurium tester strains TA100, TA1535, and TA98, but not TA102 [92]. Reversion of TA100 and TA1535 requires mutations at a GC base pair and reversion of TA98 requires a frameshift mutation near a CG base pair [94]. TA102 has an AT base pair at the site of reversion [94]. Based on these observations, it was concluded that pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts formed at GC base pairs were mutagenic, at least in bacteria. However, we cannot rule out that adducts at AT base pairs are not mutagenic in this study since TA102 has an active NER system [94] that could be repairing any mutagenic adducts at AT base pairs. TA100, TA1535, and TA98 lack UvrB and, as a result, do not have an functional NER system [94].

One candidate adduct for the mutagenicity observed in TA100 and TA1535 is O 6-pobdG. This adduct is poorly repaired by bacterial AGT [66]. Consistent with its possible role in NNKOAc-induced mutagenicity is the observation that the mutagenic activity of NNKOAc was reduced by roughly 80% in bacteria expressing human AGT [87]. These studies were performed in S. typhimurium strain YG7108 which is a derivative of TA1535 that lacks both bacterial AGT genes, ada and ogt [95]. Since the levels of O 6-pobdG were reduced in the strain expressing human AGT by about 66% [87], these data are consistent with the hypothesis that O 6-pobdG is a significant contributor to the mutagenic activity of pyridyloxobutylating agents at GC base pairs. Other contributors may include O 2-pobC and 7-pobG. However, these two adducts are not substrates for human AGT.

NNKOAc also induced mutations in the hprt gene in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells [67]. Analysis of the mutational spectrum indicated that the bulk of the mutations occurred at AT base pairs [67]. Most of the AT mutations were AT to CG transversion mutations. There were also a small portion of AT to TA transversions and AT to GC transitional mutations. Approximately 20% of the mutations were at GC base pairs with the majority of these being GC to AT transitional mutations.

Loss of NER through ERCC-2 mutation results in an increase in mutation frequency induced by NNKOAc in CHO cells [67]. This loss reduced the rate of O 2-pobdT repair in these cells. In addition, there was a corresponding increase in the frequency of AT to TA mutations relative to the control cell line. Therefore, it is likely that O 2-pobdT triggers AT to TA mutations. This conclusion is supported by the observation that another O 2-alkyl-2′-deoxythymidine adduct, O 2-ethyl-2′-deoxythymidine, also induces AT to TA mutations [96]. Loss of BER through loss of XRCC1 also led to an increase in AT to TA mutations [67], suggesting that this repair pathway is involved in repair of pyridyloxobutyl DNA damage at AT base pairs. One possibility is that O 2-pobdT is a substrate for BER glycosylases and the result abasic sites are responsible for observed increase in AT to TA mutations observed in the cells lacking BER. This hypothesis is supported by the report that site-specifically incorporated abasic sites primarily induce transversion mutations with AT to TA mutations being more abundant than AT to GC mutations [97].

Expression of human AGT in CHO cells did not significantly impact the mutation frequency of NNKOAc [67]. However, mutations at GC base pairs represented only approximately 20% of the detected mutations. There was a reduction in the GC to AT mutations in these cells but this reduction did not significantly affect the mutation frequency. Since there was almost complete repair of O 6-pobdG, these data support the hypothesis that O 6-pobdG is responsible for the GC to AT transitional mutations triggered by pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts.

In vivo studies investigating the mutagenic properties of the pyridyloxobutylation pathway are limited. Mutations were observed in the 12th codon of K-ras in lung tumors of A/J mice receiving multiple doses of NNKOAc [98]. Since these mutations were GC to AT transitions and GC to TA transversions, it is likely that O 6-pobdG is responsible, in part, for these mutations. Both NNK and NNN have been shown to be mutagenic in target tissues in lacZ and lacI transgenic mice [88, 99–101]. The resulting transgene mutation spectra have only been reported for NNK [88, 101]. NNK induced an increased rate of GC to AT transitional mutations at non-CpG sites as well as AT to TA transitional mutations and a mixture of transversion mutations (AT to GC, AT to CG, GC to CG, and GC to TA). Since NNK both methylates and pyridyloxobutylates DNA, it is difficult to associate specific mutations with specific adducts. However, it is clear that the mutational spectrum is substantially more complicated than that observed for simple methylating nitrosamines like dimethylnitrosamine, which primarily induces GC to AT transitional mutations at non-CpG sites [102–104].

Collectively, the data presented above indicate that there are several mutagenic DNA adducts formed upon pyridyloxobutylation of DNA. These include O 6-pobdG and O 2-pobdT. Other adducts likely contribute as well. Which adducts contribute to the carcinogenic properties of this pathway are likely to depend on the biological system. If mutations at AT base pairs are required to produce proteins with oncogenic function, the formation of O 2-pobdT and its repair is probably important for tumor initiation by this pathway. On the other hand, if mutations at GC base pairs are important for triggering the carcinogenic process, the formation and persistence of O 6-pobdG will be linked to tumor formation. For example, GC to AT and GC to TA mutations were observed in the 12th codon of K-ras in lung tumors of A/J mice receiving multiple doses of NNKOAc [98]. It is likely that O 6-pobdG is responsible, in part, for these mutations. Future studies are required to better define the toxicological properties of all pyridyloxobutyl adducts and to determine the repair pathways responsible for protecting against their genotoxic effects. An understanding of these fundamental biochemical issues may help in understanding the individual differences in susceptibility to lung cancer risk associated with tobacco use.

Acknowledgment

The research in the Peterson Laboratory has been funded by CA-59887 and CA-115309.

References

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking. 83rd edition. Lyon, France: IARC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Cancer. Fact Sheet No. 297. 2009 http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/print.html.

- 3.Hoffmann D, Hecht S. Advances in tobacco carcinogenesis. In: Cooper CS, Grover PL, editors. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1990. pp. 63–102. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wogan GN, Hecht SS, Felton JS, Conney AH, Loeb LA. Environmental and chemical carcinogenesis. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2004;14(6):473–486. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodgman A, Perfetti TA. The Chemical Components of Tobacco and Tobacco Smoke. Boca Rotan, Fla, USA: CRC Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hecht SS. Tobacco smoke carcinogens and lung cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1999;91(14):1194–1210. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.14.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hecht SS, Hoffmann D. Tobacco-specific nitrosamines, an important group of carcinogens in tobacco and tobacco smoke. Carcinogenesis. 1988;9(6):875–884. doi: 10.1093/carcin/9.6.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hecht SS. Biochemistry, biology, and carcinogenicity of tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 1998;11(6):559–603. doi: 10.1021/tx980005y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hecht SS, Chen CB, Ohmori T, Hoffmann D. Comparative carcinogenicity in F344 rats of the tobacco-specific nitrosamines, N′-nitrosonornicotine and 4-(N-methyl-N-nitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone. Cancer Research. 1980;40(2):298–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivenson A, Hoffmann D, Prokopczyk B, Amin S, Hecht SS. Induction of lung and exocrine pancreas tumors in F344 rats by tobacco-specific and areca-derived N-nitrosamines. Cancer Research. 1988;48(23):6912–6917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hecht SS, Morse MA, Amin S, et al. Rapid single-dose model for lung tumor induction in A/J mice by 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and the effect of diet. Carcinogenesis. 1989;10(10):1901–1904. doi: 10.1093/carcin/10.10.1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devesa SS, Bray F, Vizcaino AP, Parkin DM. International lung cancer trends by histologic type: male:female differences diminishing and adenocarcinoma rates rising. International Journal of Cancer. 2005;117(2):294–299. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen F, Bina WF, Cole P. Declining incidence rate of lung adenocarcinoma in the United States. Chest. 2007;131(4):1000–1005. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thun MJ, Lally CA, Flannery JT, Calle EE, Flanders WD, Heath CW., Jr. Cigarette smoking and changes in the histopathology of lung cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1997;89(21):1580–1586. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.21.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann D, Rivenson A, Murphy SE, Chung F-L, Amin S, Hecht SS. Cigarette smoking and adenocarcinoma of the lung: the relevance of nicotine-derived N-nitrosamines. Journal of Smoking-Related Disorders. 1993;4(3):165–189. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wynder EL, Hoffmann D. Smoking and lung cancer: scientific challenges and opportunities. Cancer Research. 1994;54(20):5284–5295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hecht SS, Carmella SG, Murphy SE, Akerkar S, Brunnemann KD, Hoffmann D. A tobacco-specific lung carcinogen in the urine of men exposed to cigarette smoke. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329(21):1543–1546. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311183292105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parsons WD, Carmella SG, Akerkar S, Bonilla LE, Hecht SS. A metabolite of the tobacco-specific lung carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone in the urine of hospital workers exposed to environmental tobacco smoke. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 1998;7(3):257–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lackmann GM, Salzberger U, Töllner U, Chen M, Carmella SG, Hecht SS. Metabolites of a tobacco-specific carcinogen in urine from newborns. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1999;91(5):459–465. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.5.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hecht SS. Carcinogen biomarkers for lung or oral cancer chemoprevention trials. IARC Scientific Publications. 2001;154:245–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stepanov I, Hecht SS. Tobacco-specific nitrosamines and their pyridine-N-glucuronides in the urine of smokers and smokeless tobacco users. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2005;14(4):885–891. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stepanov I, Hecht SS. Detection and quantitation of N′-nitrosonornicotine in human toenails by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2008;17(4):945–948. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stepanov I, Carmella SG, Han S, et al. Evidence for endogenous formation of N′-nitrosonornicotine in some long-term nicotine patch users. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2009;11(1):99–105. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kavvadias D, Scherer G, Urban M, et al. Simultaneous determination of four tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines (TSNA) in human urine. Journal of Chromatography B. 2009;877(11-12):1185–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kavvadias D, Scherer G, Cheung F, Errington G, Shepperd J, McEwan M. Determination of tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines in urine of smokers and non-smokers. Biomarkers. 2009;14(8):547–553. doi: 10.3109/13547500903242883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weng Y, Fang C, Turesky RJ, Behr M, Kaminsky LS, Ding X. Determination of the role of target tissue metabolism in lung carcinogenesis using conditional cytochrome P450 reductase-null mice. Cancer Research. 2007;67(16):7825–7832. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belinsky SA, White CM, Boucheron JA. Accumulation and persistence of DNA adducts in respiratory tissue of rats following multiple administrations of the tobacco specific carcinogen 4-(N-methyl-N-nitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone. Cancer Research. 1986;46(3):1280–1284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hecht SS, Trushin N, Castonguay A, Rivenson A. Comparative tumorigenicity and DNA methylation in F344 rats by 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and N-nitrosodimethylamine. Cancer Research. 1986;46(2):498–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belinsky SA, Foley JF, White CM, Anderson MW, Maronpot RR. Dose-response relationship between O 6-methylguanine formation in Clara cells and induction of pulmonary neoplasia in the rat by NNK. Cancer Research. 1990;50(12):3772–3780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy SE, Palomino A, Hecht SS, Hoffmann D. Dose-response study of DNA and hemoglobin adduct formation by 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone in F344 rats. Cancer Research. 1990;50(17):5446–5452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peterson LA, Hecht SS. O 6-Methylguanine is a critical determinant of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone tumorigenesis in A/J mouse lung. Cancer Research. 1991;51(20):5557–5564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loechler EL, Green CL, Essigmann JM. In vivo mutagenesis by O 6-methylguanine built into a unique site in a viral genome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1984;81:6271–6275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.20.6271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bishop RE, Pauly GT, Moschel RC. O 6-Ethylguanine and O 6-benzylguanine incorporated site-specifically in codon 12 of the rat H-ras gene induce semi-targeted as well as targeted mutations in Rat4 cells. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17(4):849–856. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.4.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaina B, Christmann M, Naumann S, Roos WP. MGMT: key node in the battle against genotoxicity, carcinogenicity and apoptosis induced by alkylating agents. DNA Repair. 2007;6(8):1079–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pegg AE. Repair of O 6-alkylguanine by alkyltransferases. Mutation Research. 2000;462(2-3):83–100. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bignami M, O’Driscoll M, Aquilina G, Karran P. Unmasking a killer: DNA O 6-methylguanine and the cytotoxicity of methylating agents. Mutation Research. 2000;462(2-3):71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swann PF. Why do O 6-alkylguanine and O 4-alkylthymine miscode? The relationship between the structure of DNA containing O 6-alkylguanine and O 4-alkylthymine and the mutagenic properties of these bases. Mutation Research. 1990;233(1-2):81–94. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(90)90153-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carmella SG, McIntee EJ, Chen M, Hecht SS. Enantiomeric composition of N′-nitrosonornicotine and N′-nitrosoanatabine in tobacco. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21(4):839–843. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.4.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McIntee EJ, Hecht SS. Metabolism of N′-nitrosonornicotine enantiomers by cultured rat esophagus and in vivo in rats. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2000;13(3):192–199. doi: 10.1021/tx990171l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Upadhyaya P, McIntee EJ, Villalta PW, Hecht SS. Identification of adducts formed in the reaction of 5′-acetoxy-N′-nitrosonornicotine with deoxyguanosine and DNA. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2006;19(3):426–435. doi: 10.1021/tx050323e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Upadhyaya P, Hecht SS. Identification of adducts formed in the reactions of 5′-acetoxy- N′-nitrosonornicotine with deoxyadenosine, thymidine, and DNA. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2008;21(11):2164–2171. doi: 10.1021/tx8002559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang M, Cheng G, Sturla SJ, et al. Identification of adducts formed by pyridyloxobutylation of deoxyguanosine and DNA by 4-(acetoxymethylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone, a chemically activated form of tobacco specific carcinogens. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2003;16(5):616–626. doi: 10.1021/tx034003b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hecht SS, Villalta PW, Sturla SJ, et al. Identification of O 2-substituted pyrimidine adducts formed in reactions of 4-(Acetoxymethylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and 4-(Acetoxymethylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol with DNA. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2004;17(5):588–597. doi: 10.1021/tx034263t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang L, Spratt TE, Liu X-K, Hecht SS, Pegg AE, Peterson LA. Pyridyloxobutyl adduct O 6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine is present in 4-(acetoxymethylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-treated DNA and is a substrate for O 6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 1997;10(5):562–567. doi: 10.1021/tx9602067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hecht SS, Spratt TE, Trushin N. Evidence for 4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobutylation of DNA in F344 rats treated with the tobacco-specific nitrosamines 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and N′-nitrosonornicotine. Carcinogenesis. 1988;9(1):161–165. doi: 10.1093/carcin/9.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sturla SJ, Scott J, Lao Y, Hecht SS, Villalta PW. Mass spectrometric analysis of relative levels of pyridyloxobutylation adducts formed in the reaction of DNA with a chemically activated form of the tobacco-specific carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2005;18(6):1048–1055. doi: 10.1021/tx050028u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cloutier J-F, Drouin R, Weinfeld M, O’Connor TR, Castonguay A. Characterization and mapping of DNA damage induced by reactive metabolites of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) at nucleotide resolution in human genomic DNA. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2001;313(3):539–557. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park S, Seetharaman M, Ogdie A, Ferguson D, Tretyakova N. 3′-Exonuclease resistance of DNA oligodeoxynucleotides containing O 6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine. Nucleic Acids Research. 2003;31(7):1984–1994. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haglund J, Henderson AP, Golding BT, Törnqvist M. Evidence for phosphate adducts in DNA from mice treated with 4-(N-methyl-N-nitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2002;15(6):773–779. doi: 10.1021/tx015542o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haglund J, Rafiq A, Ehrenberg L, Golding BT, Törnqvist M. Transalkylation of phosphotriesters using Cob(I)alamin: toward specific determination of DNA-phosphate adducts. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2000;13(4):253–256. doi: 10.1021/tx990135m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang M, Cheng G, Villalta PW, Hecht SS. Development of liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry methods for analysis of DNA adducts of formaldehyde and their application to rats treated with N-nitrosodimethylamine or 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2007;20(8):1141–1148. doi: 10.1021/tx700189c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hecht SS. DNA adduct formation from tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. Mutation Research. 1999;424(1-2):127–142. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Staretz ME, Foiles PG, Miglietta LM, Hecht SS. Evidence for an important role of DNA pyridyloxobutylation in rat lung carcinogenesis by 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone: effects of dose and phenethyl isothiocyanate. Cancer Research. 1997;57(2):259–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thomson NM, Kenney PM, Peterson LA. The pyridyloxobutyl DNA adduct, O 6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine, is detected in tissues from 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-treated A/J mice. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2003;16(1):1–6. doi: 10.1021/tx025585k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomson NM, Mijal RS, Ziegel R, et al. Development of a quantitative liquid chromatography/electrospray mass spectrometric assay for a mutagenic tobacco specific nitrosamine-derived DNA adduct, O 6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]-2′-deoxyguanosine. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2004;17(12):1600–1606. doi: 10.1021/tx0498298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lao Y, Villalta PW, Sturla SJ, Wang M, Hecht SS. Quantitation of pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts of tobacco-specific nitrosamines in rat tissue DNA by high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2006;19(5):674–682. doi: 10.1021/tx050351x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lao Y, Yu N, Kassie F, Villalta PW, Hecht SS. Formation and accumulation of pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts in F344 rats chronically treated with 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and enantiomers of its metabolite, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2007;20(2):235–245. doi: 10.1021/tx060207r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Upadhyaya P, Lindgren BR, Hecht SS. Comparative levels of O 6-methylguanine, pyridyloxobutyl-, and pyridylhydroxybutyl-DNA adducts in lung and liver of rats treated chronically with the tobacco-specific carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1- butanone. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2009;37(6):1147–1151. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.027078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang S, Wang M, Villalta PW, et al. Analysis of pyridyloxobutyl and pyridylhydroxybutyl DNA adducts in extrahepatic tissues of F344 rats treated chronically with 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and enantiomers of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2009;22(5):926–936. doi: 10.1021/tx900015d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lao Y, Yu N, Kassie F, Villalta PW, Hecht SS. Analysis of pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts in F344 rats chronically treated with (R)- and (S)-N′-nitrosonornicotine. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2007;20(2):246–256. doi: 10.1021/tx060208j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang S, Wang M, Villalta PW, Lindgren BR, Lao Y, Hecht SS. Quantitation of pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts in nasal and oral mucosa of rats treated chronically with enantiomers of N′-nitrosonornicotine. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2009;22(5):949–956. doi: 10.1021/tx900040j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hölzle D, Schlöbe D, Tricker AR, Richter E. Mass spectrometric analysis of 4-hydroxy-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-releasing DNA adducts in human lung. Toxicology. 2007;232(3):277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schlöbe D, Hölzle D, Hatz D, von Meyer L, Tricker AR, Richter E. 4-Hydroxy-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-releasing DNA adducts in lung, lower esophagus and cardia of sudden death victims. Toxicology. 2008;245(1-2):154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Daniels DS, Mol CD, Arvai AS, Kanugula S, Pegg AE, Tainer JA. Active and alkylated human AGT structures: a novel zinc site, inhibitor and extrahelical base binding. EMBO Journal. 2000;19(7):1719–1730. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xu-Welliver M, Pegg AE. Degradation of the alkylated form of the DNA repair protein, O 6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23(5):823–830. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.5.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mijal RS, Thomson NM, Fleischer NL, et al. The repair of the tobacco specific nitrosamine derived adduct O 6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine by O 6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase variants. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2004;17(3):424–434. doi: 10.1021/tx0342417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li L, Perdigao J, Pegg AE, et al. The influence of repair pathways on the cytotoxicity and mutagenicity induced by the pyridyloxobutylation pathway of tobacco-specific nitrosamines. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2009;22(8):1464–1472. doi: 10.1021/tx9001572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fromme JC, Banerjee A, Verdine GL. DNA glycosylase recognition and catalysis. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2004;14(1):43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fortini P, Pascucci B, Parlanti E, D’Errico M, Simonelli V, Dogliotti E. The base excision repair: mechanisms and its relevance for cancer susceptibility. Biochimie. 2003;85(11):1053–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wyatt MD, Pittman DL. Methylating agents and DNA repair responses: methylated bases and sources of strand breaks. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2006;19(12):1580–1594. doi: 10.1021/tx060164e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Airoldi L, Magagnotti C, Bonfanti M, et al. Detection of O 6-butyl- and O 6-(4-hydroxybutyl)guanine in urothelial and hepatic DNA of rats given the bladder carcinogen N-nitrosobutyl(4-hydroxybutyl)amine. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15(10):2297–2301. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.10.2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lacoste S, Castonguay A, Drouin R. Formamidopyrimidine adducts are detected using the comet assay in human cells treated with reactive metabolites of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) Mutation Research . 2006;600(1-2):138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fan J, Wilson DM., III Protein-protein interactions and posttranslational modifications in mammalian base excision repair. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2005;38(9):1121–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Petit C, Sancar A. Nucleotide excision repair: from E. coli to man. Biochimie. 1999;81(1-2):15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(99)80034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Ünsal-Kaçmaz K, Linn S. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2004;73:39–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brown PJ, Bedard LL, Massey TE. Repair of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-induced DNA pyridyloxobutylation by nucleotide excision repair. Cancer Letters. 2008;260(1-2):48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thompson LH, Brookman KW, Dillehay LE. Hypersensitivity to mutation and sister-chromatid-exchange induction in CHO cell mutants defective in incising DNA containing UV lesions. Somatic Cell Genetics. 1982;8(6):759–773. doi: 10.1007/BF01543017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chambers RW, Sledziewska-Gojska E, Hirani-Hojatti S, Borowy-Borowski H. uvrA and recA mutations inhibit a site-specific transition produced by a single O 6-methylguanine in gene G of bacteriophage ΦX174. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1985;82(21):7173–7177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.21.7173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chambers RW, Sledziewska-Gojska E, Hirani-Hojatti S. In vivo effect of DNA repair on the transition frequency produced from a single O 6-methyl-or O 6-n-butyl-guanine in a T:G base pair. Molecular & General Genetics. 1988;213(2-3):325–331. doi: 10.1007/BF00339598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bol SAM, van Steeg H, van Oostrom CTHM, et al. Nucleotide excision repair modulates the cytotoxic and mutagenic effects of N-butyl-N-nitrosourea in cultured mammalian cells as well as in mouse splenocytes in vivo . Mutagenesis. 1999;14(3):317–322. doi: 10.1093/mutage/14.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Boyle JM, Saffhill R, Margison GP, Fox M. A comparison of cell survival, mutation and persistence of putative promutagenic lesions in Chinese hamster cells exposed to BNU or MNU. Carcinogenesis. 1986;7(12):1981–1985. doi: 10.1093/carcin/7.12.1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Boyle JM, Margison GP, Saffhill R. Evidence for the excision repair of O 6-n-butyldeoxyguanosine in human cells. Carcinogenesis. 1986;7(12):1987–1990. doi: 10.1093/carcin/7.12.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Duckett DR, Drummond JT, Murchie AIH, et al. Human MutSα recognizes damaged DNA base pairs containing O 6 methylguanine, O 4-methylthymine, or the cisplatin d(GpG) adduct. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:6443–6447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu J, Gu L, Wang H, Geacintov NE, Li G-M. Mismatch repair processing of carcinogen-DNA adducts triggers apoptosis. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1999;19(12):8292–8301. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Christmann M, Tomicic MT, Roos WP, Kaina B. Mechanisms of human DNA repair: an update. Toxicology. 2003;193(1-2):3–34. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hoeijmakers JHJ. Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer. Nature. 2001;411(6835):366–374. doi: 10.1038/35077232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mijal RS, Loktionova NA, Vu CC, Pegg AE, Peterson LA. O 6-pyridyloxobutylguanine adducts contribute to the mutagenic properties of pyridyloxobutylating agents. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2005;18(10):1619–1625. doi: 10.1021/tx050139t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sandercock LE, Hahn JN, Li L, et al. Mgmt deficiency alters the in vivo mutational spectrum of tissues exposed to the tobacco carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(4):866–874. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Peterson LA, Thomson NM, Crankshaw DL, Donaldson EE, Kenney PJ. Interactions between methylating and pyridyloxobutylating agents in A/J mouse lungs: implications for 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-induced lung tumorigenesis. Cancer Research. 2001;61(15):5757–5763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brown PJ, Massey TE. In vivo treatment with 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) induces organ-specific alterations in in vitro repair of DNA pyridyloxobutylation. Mutation Research. 2009;663(1-2):15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hecht SS, Lin D, Castonguay A. Effects of α-deuterium substitution on the mutagenicity of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) Carcinogenesis. 1983;4(3):305–310. doi: 10.1093/carcin/4.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Foiles PG, Petersen LA, Miglietta LM, Ronai Z. Analysis of mutagenic activity and ability to induce replication of polyoma DNA sequences by different model metabolites of the carcinogenic tobacco-specific nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone. Mutation Research. 1992;279(2):91–101. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(92)90250-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pauly GT, Peterson LA, Moschel RC. Mutagenesis by O 6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine in Escherichia coli and human cells. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2002;15(2):165–169. doi: 10.1021/tx0101245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Maron DM, Ames BN. Revised methods for the salmonella mutagenicity test. Mutation Research. 1983;113(3-4):173–215. doi: 10.1016/0165-1161(83)90010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yamada M, Sedgwick B, Sofuni T, Nohmi T. Construction and characterization of mutants of Salmonella typhimurium deficient in DNA repair of O 6-methylguanine. Journal of Bacteriology. 1995;177(6):1511–1519. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.6.1511-1519.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bhanot OS, Grevatt PC, Donahue JM, Gabrielides CN, Solomon JJ. In vitro DNA replication implicates O2-ethyldeoxythymidine in transversion mutagenesis by ethylating agents. Nucleic Acids Research. 1992;20(3):587–594. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.3.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Simonelli V, Narciso L, Dogliotti E, Fortini P. Base excision repair intermediates are mutagenic in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33(14):4404–4411. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ronai ZA, Gradia S, Peterson LA, Hecht SS. G to A transitions and G to T transversions in codon 12 of the Ki-ras oncogene isolated from mouse lung tumors induced by 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and related DNA methylating and pyridyloxobutylating agents. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14(11):2419–2422. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.11.2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.von Pressentin MDM, Kosinska W, Guttenplan JB. Mutagenesis induced by oral carcinogens in lacZ mouse (MutaMouse) tongue and other oral tissues. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20(11):2167–2170. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.11.2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.von Pressentin MDM, Chen M, Guttenplan JB. Mutagenesis induced by 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanose-4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and N-nitrosonornicotine in lacZ upper aerodigestive tissue and liver and inhibition by green tea. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22(1):203–206. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hashimoto K, Ohsawa K-I, Kimura M. Mutations induced by 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) in the lacZ and cII genes of Muta Mouse. Mutation Research. 2004;560(2):119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wang X, Suzuki T, Itoh T, et al. Specific mutational spectrum of dimethylnitrosamine in the lad transgene of big blue C57BL/6 mice. Mutagenesis. 1998;13(6):625–630. doi: 10.1093/mutage/13.6.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Souliotis VL, van Delft JHM, Steenwinkel M-JST, Baan RA, Kyrtopoulos SA. DNA adducts, mutant frequencies and mutation spectra in λ lacZ transgenic mice treated with N-nitrosodimethylamine. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19(5):731–739. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.5.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shane BS, Smith-Dunn DL, de Boer JG, Glickman BW, Cunningham ML. Mutant frequencies and mutation spectra of dimethylnitrosamine (DMN) at the lacI and cII loci in the livers of Big Blue transgenic mice. Mutation Research. 2000;452(2):197–210. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]