Abstract

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) is a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily and is well known to act as the molecular target for lipid-lowering drugs of the fibrate family. At the molecular level, PPARα regulates the transcription of a number of genes critical for lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. PPARα activators are further shown to reduce body weight gain and adiposity, at least in part, due to the increase of hepatic fatty acid oxidation and the decrease in levels of circulating triglycerides responsible for adipose cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia. However, these effects of the PPARα ligand fenofibrate on obesity are regulated with sexual dimorphism and seem to be influenced by the presence of functioning ovaries, suggesting the involvement of ovarian steroids in the control of obesity by PPARα. In female ovariectomized mice, 17β-estradiol inhibits the actions of fenofibrate on obesity through its suppressive effects on the expression of PPARα target genes, and these processes may be mediated by inhibiting the coactivator recruitment of PPARα. Thus, it is likely that PPARα functions on obesity may be enhanced in estrogen-deficient states.

1. Introduction

Obesity is the result of an energy imbalance caused by an increased ratio of caloric intake to energy expenditure. In conjunction with obesity, related metabolic disorders such as dyslipidemia, atherosclerosis, and type 2 diabetes have become global health problems. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) have been the subject of intense investigation and considerable pharmacological research due to the fact that they are involved in the improvement of these chronic diseases. Three PPAR isotypes have been identified: PPARα, PPARγ, and PPARβ/δ, each with different ligand specificity, very distinct tissue distributions, and different biological functions.

Among the three subtypes, PPARα is expressed predominantly in tissues that have a high level of fatty acid (FA) catabolism such as liver, heart, and muscle [1–3]. PPARα regulates the expression of a large number of genes that affect lipid and lipoprotein metabolism [4–7]. PPARα ligands fibrates have been used for the treatment of dyslipidemia due to their ability to lower plasma triglyceride levels and elevate HDL cholesterol levels. PPARα is also thought to be involved in energy metabolism. Since PPARα ligands fibrates stimulate hepatic FA oxidation and thus reduce the levels of plasma triglycerides responsible for adipose cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia, PPARα may be important in the control of adiposity and body weight due to its ability to regulate an overall energy balance. This notion is supported by findings showing that PPARα-deficient mice exhibited abnormalities in triglyceride and cholesterol metabolism and became obese with age [8]. Furthermore, several studies have suggested that fibrates can modulate body weight and adiposity in experimental animal models, such as fatty Zucker rats, high fat-fed C57BL/6 mice, and high fat-fed obese rats [9–11].

Energy balance seems to be influenced by gonadal sex steroids [12]. Female sex steroid hormones have been the subject of intense investigation over the last several decades based on the role that these ovarian hormones play in regulating food intake, body weight, and lipid metabolism. For example, ovariectomized (OVX) animals and postmenopausal women show increased food intake, body weight, and adipose tissue mass, as well as decreased FA oxidation and triglyceride lipolysis, indicating the involvement of gonadal steroids in the modulation of obesity [13–16]. Several lines of study show that ovarian steroids, in particular estrogens, can affect obesity and the related disorders of dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) [12]. Estrogen insufficiency is known to be largely responsible for increased adiposity and circulating lipids in OVX rodents because such animals do not display obesity, adiposity, and lipid disorders when they are administered exogenous estrogens [17–19]. Moreover, my previous results demonstrated that fenofibrate reduced body weight and white adipose tissue (WAT) mass in male and female OVX mice [20–23]. Although the administration of 17β-estradiol (E2) or fenofibrate alone effectively reduces body weight gain and WAT mass in female OVX mice, fenofibrate treatment does not prevent gains in body weight and WAT mass in the presence of ovaries. Interestingly, there are data indicating that PPAR/RXR heterodimers are capable of binding to estrogen response elements (EREs), and PPAR and estrogen receptors (ERs) share cofactors [24–28], suggesting that signal cross-talk may exist between PPARα and ERs in the control of obesity.

Based on my published results showing the fenofibrate functions on obesity during various conditions, this paper will focus on the differential regulation of PPARα on obesity by sex differences and the interaction of PPARα and ERs in the regulation of obesity.

2. General Aspects of PPARα and ERs

2.1. PPARα and ERs as Nuclear Hormone Receptors

Both PPARα and ERs belong to the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily, which has a typical structure consisting of six functional domains, A/B, C, D, and E/F (Figure 1) [29–31]. The amino-terminal A/B domain contains a ligand-independent activation function-1 (AF-1). The C or DNA binding domain (DBD) contains the structure of the two zinc fingers and α-helical DNA motifs. The DBD directs nuclear receptors to the hormone response elements (HREs) of target genes. The D region is a highly flexible hinge region and may be involved in protein-protein interactions, such as receptor dimerization and efficient binding of DBD to HREs. The E/F domain is responsible for ligand-binding and is thus named the ligand binding domain (LBD). The interaction of nuclear receptors with their ligands induces conformational changes that include the AF-2 ligand-dependent activation domain, which is located in the C-terminal α-helix. AF-2 regulates ligand-dependent transactivation, recruitment of coactivators, and release of corepressors. In addition, AF-2 is also important for receptor dimerization.

Figure 1.

Schematic structure of the functional domains of nuclear receptors. The activation domains AF-1 and AF-2 are located at the N-terminal and C-terminal regions, respectively. C domain is a highly conserved DNA-binding domain. D domain is a highly flexible hinge region. E/E domain is responsible for ligand-binding and converting nuclear receptors to active forms that bind DNA. Adapted from [29].

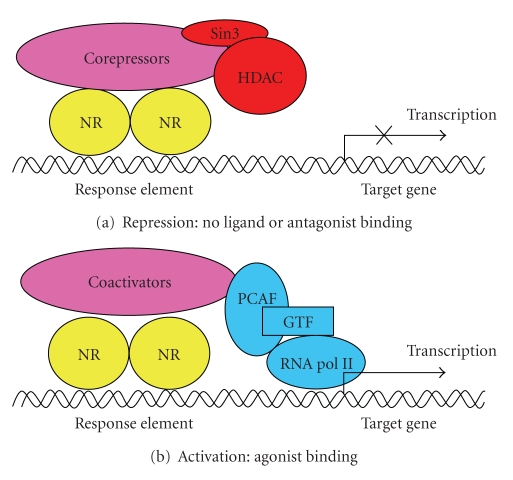

Molecular signaling of PPARα and ERs functions is similar [34–37]. In the unliganded or antagonist-bound state, they are associated with corepressor proteins such as nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR) or silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor (SMRT) (Figure 2(a)). After binding within the LBD, PPARα ligands induce heterodimerization with retinoid X receptor (RXR) and the subsequent interaction with coactivators like CREB-binding protein (CBP) or steroid receptor coactivators, followed by binding to PPAR response elements (PPREs) within target gene promoters (Figure 2(b)). Similarly, ligand-activated ERs bind to their half-site-containing EREs as homodimers following the recruitment of coactivators. Importantly, PPARα shares a similar pool of cofactors with ERs which provides a basis for mutual interactions between these receptors [34, 35].

Figure 2.

Activation and repression of nuclear receptor activity. (a) In the absence of ligand, nuclear receptors (NRs) are associated with corepressor complexes that bind Sin3 and histone deacetylase (HDAC), thereby turning off gene transcription. Some steroid receptors can recruit this complex when they are occupied by antagonists although they do not seem to be associated with corepressors in the unliganded state. (b) In the presence of ligand, NRs generally recruit coactivator complexes, PCAF histone acetyltransferase protein, general transcription factors, and RNA polymerase II to induce gene transcription. GTF: general transcription factor; RNA pol II: RNA polymerase II; PCAF: P300/CBP-associated factor.

2.2. PPARα

PPARα was the first PPAR to be identified by Issemann and Green in 1990, and human PPARα was cloned by Sher et al. in 1993 [1, 38]. PPARα is predominantly expressed in tissues with high rates for mitochondrial and peroxisomal FA catabolism such as liver, brown adipose tissue (BAT), heart, skeletal muscle, kidney, and intestinal mucosa [1–3]. Significant amounts of PPARα are present in different immunological and vascular wall cell types [39, 40].

PPARα acts as a ligand-activated transcription factor. PPARα mediates the physiological and pharmacological signaling of synthetic or endogenous PPARα ligands. FAs and FA-derived compounds are natural ligands for PPARα. Modified FAs, conjugated FAs, oxidized phospholipids, and FA-derived eicosanoids such as 8-S-hydroxytetraenoic acid and leukotriene B4 activate PPARα [41]. Synthetic compounds can also activate PPARα. These compounds include carbaprostacyclin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, pirinixic acid (also known as Wy14,643), phthalate ester plasticizers, and hypolipidemic drugs fibrates [41]. Of the currently used fibrates, fenofibrate, gemfibrozil, clofibrate, and ciprofibrate preferentially activate PPARα whereas bezafibrate activates all three PPARs. Novel PPARα/γ dual agonists and PPARα/γ/δ pan agonists with PPAR selective modulator activity are under development as drug candidates [42, 43].

PPARα regulates the expression of a number of genes critical for lipid and lipoprotein metabolism, thereby leading to lipid homeostasis. Ligand-bound PPARα heterodimerizes with RXR and binds to direct repeat PPREs in the promoter region of target genes (Figure 3(a)). PPARα target genes include those involved in the hydrolysis of plasma triglycerides, FA uptake and binding, and FA β–oxidation (Table 1). Genes involved in the HDL metabolism are also regulated by PPARα. The activation of PPARα target genes therefore promotes increased β-oxidation of FAs, as well as the decrease in high circulating triglyceride levels and increased high HDL cholesterol levels, leading to lipid homeostasis.

Figure 3.

The signaling pathways of P P A R α and estrogen receptors. (a) After activation by its respective ligands, PPARα heterodimerizes with retinoid X receptor and binds to direct repeat PPRE in the promoters of target genes to drive expression of target genes. (b) Estrogen-bound estrogen receptors recognize palindromic ERE to directly bind this DNA and ultimately increase gene expression. RXR: retinoid X receptor; PPRE: PPAR response element; ERE: estrogen response element; ERs: estrogen receptors.

Table 1.

PPARα target genes involved in lipid homeostasis.

| Target genes | Gene expression |

|---|---|

| Fatty acid uptake, binding, and activation | |

| Fatty acid transport protein (FATP) | Stimulation |

| Fatty acid translocase (FAT/CD36) | Stimulation |

| Liver cytosolic fatty acid-binding protein (L-FABP) | Stimulation |

| Acyl-CoA synthetase (ACS) | Stimulation |

| Carnitine palmitoyltransferase I and II (CPT-1and CPT-II) | Stimulation |

| Mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation | |

| Very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (VLCAD) | Stimulation |

| Long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCAD) | Stimulation |

| Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) | Stimulation |

| Short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCAD) | Stimulation |

| Peroxisomal fatty acid β-oxidation | |

| Acyl-CoA oxidase (ACOX) | Stimulation |

| Bifunctional enzyme (HD) | Stimulation |

| 3-Ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (Thiolase) | Stimulation |

| Hydrolysis of plasma triglycerides | |

| lipoprotein lipase (LPL) | Stimulation |

| Apolipoprotein C-III (Apo C-III) | Inhibition |

| Fatty acid synthesis | |

| Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) | Inhibition |

| Fatty acid synthase (FAS) | Inhibition |

| HDL metabolism | |

| Apolipoprotein A-I and A-II (ApoA-I and ApoA-II) | Stimulation |

| ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 (ABCA1) | Stimulation |

| Electron transport chain | |

| Uncoupling protein 1, 2, and 3 (UCP1, 2, and 3) | Stimulation |

In addition to PPARα regulation of genes for lipid and lipoprotein metabolism, PPARα regulates the expression of uncoupling proteins (UCPs), which contain PPRE in their promoters. PPARα activators increase the mRNA levels of UCP1 in BAT, UCP2 in liver, and UCP3 in skeletal muscle. UCP1 regulates energy expenditure through thermogenesis. Reductions in body weight and adiposity by fenofibrate are associated with elevation of hepatic UCP2 expression [44]. Transgenic mice overexpressing UCP3 in their skeletal muscle exhibit increased FA oxidation and are resistant to diet-induced obesity. Thus, PPARα may be involved in energy balance and obesity by regulating UCPs [45].

In addition to the important roles of PPARα in FA oxidation in liver and skeletal muscle, PPARα activators may affect adipose tissue metabolism. For example, administration of bezafibrate, a typical PPAR activator, leads to dedifferentiation of adipocytes into preadipocyte-like cells through the activation of genes involved in both mitochondrial and peroxisomal β-oxidation [46]. The PPARα ligand GI259578A decreases the mean size of adipocytes in WAT [47]. This is supported by my recent report that fenofibrate stimulates FA β–oxidation in both epididymal adipose tissue and differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes [48].

PPARα may be involved in the regulation of energy balance through fat catabolism. Since fenofibrate increases hepatic FA oxidation and thus decreases the levels of plasma triglycerides responsible for adipose cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia, it may inhibit an increase in body weight. This is supported by a report that PPARα-deficient mice showed abnormal triglyceride and cholesterol metabolism and became obese with age [8]. Expression of PPARα and FA oxidative PPARα target genes is suppressed in obese mice [49]. Many studies show that fenofibrate can modulate body weight in animal models of diabetes, obesity, and insulin resistance although another known PPARα stimulator perfluorooctanoic acid induces overweight at low doses in intact female mice [9–11, 50].

PPARα also regulates insulin resistance and diabetes due to visceral obesity. Fenofibrate prevents adipocyte hypertrophy and insulin resistance by increasing FA β-oxidation and intracellular lipolysis from visceral adipose tissue, showing that PPARα may be one of the major factors leading to decreased adipocyte size and improved insulin sensitivity [48]. Moreover, PPARα agonist treatment has been reported to improve pancreatic β-cell function in insulin-resistant rodents and the adaptive response of the pancreatic β-cell function to pathological conditions, such as obesity [51, 52]. In addition, PPARα agonists, including fibrates, normalize atherogenic lipid profile, as well as several cardiovascular risk markers [53].

2.3. ERs

Like PPARα, ERs function as ligand-dependent transcription factors belonging to members of the nuclear hormone receptor family. Two major ERs (ERα and ERβ) mediate the physiological and pharmacological signals of natural or synthetic ER activators. Upon estrogen binding, ERs are activated and act as transcriptional modulators by binding to palindromic EREs in the promoter region of target genes (Figure 3(b)) [54, 55]. ERs are also activated by specific synthetic ligands such as raloxifene, tamoxifen, and the ERβ-specific ligand diarylpropionitrile. ERα is mainly expressed in the female reproductive system such as ovary, uterus, pituitary, and mammary glands but is also present in the hypothalamus, brain, bone, liver, WAT, skeletal muscle, and the cardiovascular system [56–58]. ERβ is expressed in many tissues including skeletal muscle, WAT, BAT, prostate, salivary glands, testis, ovary, vascular endothelium, the immune system, and certain neurons of the central and peripheral nervous system [59, 60].

The natural forms of estrogens are E2, estrone, and estriol. E2 potently activates ER-mediated transcriptional activity to a greater extent than estrone or estriol. E2 has been considered one of the most important hormones in female physiology and reproduction for a long period . However, we now know that E2 also plays a protective role in a variety of pathophysiological states, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, osteoporosis, and cancer in both men and women [61].

E2 is involved in the regulation of adiposity and obesity, and visceral fat varies inversely with E2 levels [62]. Accumulation of visceral fat occurs in females when E2 levels become sufficiently low. In rodents, ovariectomy leads to weight gain primarily in the form of adipose tissue, which is reversed by physiologic E2 replacement [12, 63–65]. Loss of circulating E2 is associated with an increase in adiposity during menopause whereas postmenopausal women who receive E2 replacement therapy do not display the characteristic abdominal weight gain pattern usually associated with menopause [13–15]. Aromatase deficiency, during which E2 is not produced, results in the development of adiposity and obesity [66]. Furthermore, ERα deficiency increased adipose tissue in both male and female mice, consistent with other reports linking estrogen with body weight regulation and adipocyte function [67]. E2 influences food intake and eventually the maintenance of normal body weight in adult females. In female dogs, a phasic decrease in food intake occurs during estrus [68]. Gradual decreases in eating through the follicular phase have been shown in monkeys, which show progressive increases in estrogens through the follicular phase comparable to those of humans [69]. E2 treatment to OVX rats normalized meal size, food intake, and body weight gain to the levels observed in intact rats [19, 70]. ERβ is involved in the anorectic action of E2. Blockade of ERβ inhibits the effects of E2 on food intake, body weight gain, and fat accumulation in OVX rats [71]. In contrast, Heine et al. [67] and D'Eon et al. [16] suggested that E2 decreases adiposity and adipocyte size in OVX mice independent of differences in energy intake, possibly through promoting fat oxidation and enhancing triglyceride breakdown [16, 67].

In addition to food intake and body weight regulation, estrogen improves glucose homeostasis and diabetes mellitus. Mice that lack ERα have insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance [67]. Both male and female aromatase-KO mice have reduced glucose oxidation, and male aromatase-KO mice develop glucose and insulin resistance that can be reversed by E2 treatment [58, 66]. ERα and ERβ modulate glucose transporter 4 expression and stimulate glucose uptake in skeletal muscle of mice [58]. Estrogens have also been shown to regulate vascular disease. Premenopausal women have a lower tendency to develop hypertension than do men of similar age, but the prevalence of CVD increases more rapidly in aging women than in men [72]. The increased incidence of CVD in aged women may be due to the development of obesity. Although the rate of increase of CVD is greater at the postmenopausal age in women than at the same age in men, the actual incidence of CVD is still less in women than in men if hypertension is not included (Framington Heart Study). Thus, estrogen signaling through ERs leads to improvement of metabolic disorders.

As mentioned above, both PPARα and ERs have similar structures, action mechanisms, and functions, suggesting the interaction of PPARα with ERs in the control of these metabolic diseases including obesity. However, signal cross-talk between PPARα and ERs in the regulation of obesity is not clear.

3. PPARα Functions on Obesity

Over the last several decades, a number of studies have been published on the physiology, pharmacology, and functional genomics of PPARα. In vivo and in vitro studies demonstrate that PPARα plays a central role in lipid and lipoprotein metabolism, and thereby decreases dyslipidemia associated with metabolic syndrome. Obesity is the leading cause for the development of metabolic diseases, such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and CVD. There are important sex differences in the prevalence of obesity-related metabolic diseases [33, 73–75]. Ovarian hormones seem to have protective roles in metabolic diseases since women with functioning ovaries have much fewer incidences of such disorders, but these metabolic diseases dramatically increase in postmenopausal women.

3.1. Fenofibrate Regulates Obesity with Sexual Dimorphism

PPARα activator fenofibrate differentially influences body weight and adiposity in both sexes of mice. Fenofibrate improves body weight gain and adiposity in high fat-diet-fed male mice, but fails to regulate them in female mice (Figure 4) [20]. In males, body weight and WAT mass increased by 44% and 77%, respectively, after 14-week administration of high fat diet. These parameters were lowered after fenofibrate treatment, more so than those of mice given a low fat diet, and the reduction in body weight correlated with a fall in adipose tissue mass. In contrast to males, fenofibrate slightly increased high fat diet-induced body weight and adipose tissue mass in female mice, suggesting a different PPARα action on females than on males in the control of obesity. Previous studies showed that fenofibrate can modulate body weight and adiposity in several animal models [9–11]. Since these results were obtained from males, fenofibrate may be an effective regulator of energy homeostasis in the male animal system. Taken together, these studies show that body weight gain and adipose tissue mass of male C57BL/6 mice were significantly reduced by fenofibrate, but those of females were not, and indicate that the action of fenofibrate on body weight and adiposity is different, depending on sex.

Figure 4.

Effects of fenofibrate on high fat diet-induced body weight gain (a) and WAT mass (b) in both sexes of C57BL/6 mice. Male and female C57BL/6 mice were received a low fat, high fat, or high fat diet supplemented with fenofibrate (0.05% w/w) for 13 weeks. Body weight at the end of the experiment are statistically different (P < .01) between high fat diet and high fat plus fenofibrate groups. #: Significantly different versus a low fat diet group, P < .05. ∗: Significantly different versus a high fat diet group, P < .01. Adapted from [20].

Although fibrates are drugs widely used to lower elevated plasma triglycerides and cholesterol, fenofibrate is shown to control lipid metabolism with sexual dimorphism. Serum concentrations of total cholesterol and triglycerides were significantly reduced by fenofibrate in male mice, similar to the previous reports [76, 77]. However, fenofibrate not only failed to decrease total cholesterol, but also decreased circulating level of triglycerides in female mice to a much lower extent than in similarly treated males. Based on the information that lipids accumulated in the adipose tissue are largely derived from circulating triglycerides, differential regulation of adiposity by fenofibrate is partly due to different levels of circulating lipids between sexes.

The regulatory effect of fenofibrate on obesity is not mediated through leptin since PPARα-knockout mice that become obese with age are not hyperphagic [8, 10]. Instead, many reports indicate that fenofibrate-regulated increases in hepatic β-oxidation are involved in this process. FA oxidation results in a decrease in FAs available for triglyceride synthesis [78, 79]. According to Yoon et al. [20], fenofibrate elevated the transcriptional activation of PPARα target genes, acyl-CoA oxidase (ACOX), enoyl-CoA hydratase/3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (HD), and thiolase in both sexes of mice [20]. However, the expression levels were much higher in males than in females, suggesting that fenofibrate exhibits sexually dimorphic activation of PPARα actions on hepatic β-oxidation, resulting in the differential energy balance with sex.

Mancini et al. [11] and Guerre-Millo et al. [10] report that fenofibrate improves obesity due to its action on FA β-oxidation in the liver and seems to act as a weight-stabilizer through its effect on liver metabolism [10, 11]. Moreover, the body weights of PPARα-deficient mice were greater than those of wild-type mice, and a marked increased amount of intra-abdominal adipose tissue was seen in PPARα-KO mice. In addition, Costet et al. [8] suggested the involvement of PPARα with a sexually dimorphic control of circulating lipids, fat storage, and obesity, in a study using male and female PPARα-null mice [8]. In contrast to these investigators, Akiyama et al. [80] provided evidence that PPARα regulates lipid metabolism but is not associated with obesity [80]. Similar to the results of Akiyama et al. [80], Yoon et al. [20] provided evidence that fenofibrate is involved in obesity, but not likely to have an effect on obesity mainly through PPARα-mediated action since it increases FA β-oxidation and decreases serum triglycerides in female mice, although their effects are much lower compared with males [20].

Overall, fenofibrate treatment affects body weight, adipose tissue mass, lipid metabolism, and hepatic β-oxidation with sexual dimorphism, but fenofibrate-regulated obesity is not directly associated with PPARα-mediated action and may be influenced by sex-related factors.

3.2. Fenofibrate Improves Male Obesity

Fenofibrate seems to suppress diet-induced obesity and severe hypertriglyceridemia caused by LDL receptor (LDLR) deficiency in male mice. The loss of LDLR increases susceptibility to diet-induced obesity and hypertriglyceridemia. Body weights and WAT mass increased in LDLR-null mice on a high fat diet compared with low fat diet controls [22, 81]. However, fenofibrate prevented the high fat diet-induced increases in body weight and WAT mass in male LDLR-null mice. The body weights of male LDLR-null mice were significantly reduced after 1 week of fenofibrate administration whereas wild-type mice showed weight decreases after 7 weeks of fenofibrate [20, 22], indicating that fenofibrate more effectively reduces body weight gain in LDLR-null mice than in wild-type mice. Interestingly, the final body weight of the fenofibrate-treated obese animals was very similar to that of lean animals on a lowfat diet. High fat diet-fed LDLR-null mice showed hepatic lipid accumulation, which was absent in the hepatocytes of mice on a low fat diet and which disappeared following fenofibrate treatment, mainly due to peroxisomal and mitochondrial β-oxidation of FAs [82, 83]. This indicates not only the prevention of body weight gain and the increased fat mobilization from WAT due to fenofibrate-induced increases of fat catabolism in the liver, but also a strong correlation between reduced body weight and decreased WAT mass by fenofibrate. In addition, fenofibrate did not affect food intake in high fat diet-induced obese LDLR-null mice. These results suggest that the increased liver activity may be paralleled by a large reduction in WAT mass, which accounts for most of the body weight reduction.

Fenofibrate also substantially decreased the increases in circulating triglycerides and total cholesterol levels, indicating that fenofibrate efficiently regulates triglyceride and cholesterol metabolism in male LDLR-null mice. Circulating triglyceride levels are thought to be regulated by the balance between its secretion and clearance. With lipoprotein catabolism suppressed, the increase in circulating triglycerides over time is indicative of the rate at which triglyceride is being secreted from the liver [84–86]. The hepatic triglyceride secretion rate was significantly lower in fenofibrate-treated mice when Triton WR1339 was used to prevent lipolysis. These observations suggest that the reduced circulating triglyceride levels after fenofibrate treatment are due to the decreased secretion of triglycerides from the liver.

The molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of fenofibrate on obesity and lipid metabolism involve the changes in the expression of apolipoprotein C-III (apo C-III) and ACOX. LDLR-null mice fed fenofibrate showed significantly lower mRNA levels of hepatic apo C-III, an apolipoprotein that limits tissue triglyceride clearance [87, 88]. Fenofibrate-activated PPARα in the liver increased mRNA levels of ACOX, the first and rate-limiting enzyme of PPARα-mediated FA β-oxidation, which resulted in reduced triglyceride production [87].

In conclusion, fenofibrate prevents both obesity and hypertriglyceridemia through hepatic PPARα activation in male LDLR-deficient mice.

3.3. Fenofibrate Regulates Female Obesity Depending on the Presence of Ovaries

Based on the suggestion that fenofibrate inhibits body weight gain and adiposity in male LDLR-null mice, it can be hypothesized that fenofibrate improves obesity in female LDLR-null mice. Body weight gain and WAT mass were significantly increased in both female OVX and sham-operated (Sham) LDLR-null mice on a high fat diet for 8 weeks. The increases in body weight and WAT mass were higher in female OVX LDLR-null mice than in Sham mice. Interestingly, fenofibrate-treated female OVX LDLR-null mice had lower body weights and WAT mass, similar to those found in several animal models, while female Sham mice did not exhibit these fenofibrate-induced reductions [21]. In db/db mice and fatty Zucker rats, the effect of fenofibrate on body weight depends on the utilization of FA, as demonstrated by a fenofibrate-induced increase of ACOX mRNA [9]. PPARα-mediated FA β-oxidation and hydrolysis of triglycerides by fenofibrate contribute to decreased body weight and WAT mass in OVX LDLR-null mice, suggesting that fenofibrate can act as a body weight-regulator in an animal model of postmenopausal women.

Serum triglycerides and total cholesterol were significantly increased in both female OVX and Sham LDLR-null mice. However, fenofibrate treatment substantially decreased high fat diet-induced increases of triglycerides and cholesterol in both female groups [9, 87]. In parallel with serum triglyceride levels, fenofibrate upregulated hepatic ACOX mRNA levels and downregulated apo C-III mRNA levels in both OVX and Sham LDLR-null mice [87, 88]. Such changes in mRNA levels of ACOX by fenofibrate were greater in female OVX LDLR-null mice than in Sham LDLR-null mice with functioning ovaries.

However, it is not likely that the PPARα-mediated reduction in serum triglycerides directly controls obesity in female Sham LDLR-null mice, which exhibited simultaneous decreases in serum triglycerides and increases in body weight and WAT mass. Thus, the effect of fenofibrate on the body weight of female Sham LDLR-null mice cannot be explained simply in terms of an altered and enhanced flux of FAs and triglycerides, since fenofibrate increased ACOX mRNA and decreased apo C-III gene expression in this group (although this expression was lower than in the OVX group). Moreover, these changes in ACOX and apo C-III mRNA did not correlate with increased body weight and adiposity. Such conflicting data suggest the possibility that this discordance may be caused by ovarian factors.

The regulation of obesity by fenofibrate in female wild-type C57BL/6J mice is similar to that in female LDLR-null mice. Fenofibrate reduced body weight gain and WAT mass in high fat diet-fed wild-type OVX mice but failed to do so in Sham mice (Figure 5(a)) [23]. Body weights of OVX mice were found to be higher than those of Sham mice 6 weeks after commencing the high fat diet. Compared to high fat diet-fed OVX mice, fenofibrate-treated OVX mice had significantly decreased body weight gain by 6 weeks into the treatment regimen and had significantly lower body weight at 13 weeks. In addition to changes in body weight, WAT mass was significantly reduced after fenofibrate treatment, and the final WAT mass of the fenofibrate-treated OVX animals was lower than that of the OVX animals on a regular chow diet. In contrast to the OVX mice, fenofibrate did not decrease body weight gain and WAT mass increases in Sham mice. These results suggest that obesity is differentially affected by fenofibrate treatment in Sham and OVX mice.

Figure 5.

Differential regulation of body weight gain (a) and PPAR α target gene expression (b) by fenofibrate depending on the presence of ovaries. Female sham-operated (Sham) and ovariectomized (OVX) mice received a low fat, high fat, or fenofibrate-supplemented (FF; 0.05% w/w) high fat diet for 13 weeks. Body weights at the end of the treatment period are significantly different not only when comparing the low fat group to either the high fat (P < .05) or high fat plus FF (P < .01) groups in female Sham mice, but also when comparing the high fat group to either the low fat (P < .01) or high fat plus FF (P < .005) groups in female OVX mice. ∗: Significantly different versus the high fat group, P < .05. #: Significantly different versus the Sham group, P < .05. ACOX: acyl-CoA oxidase; HD: enoyl-CoA hydratase/3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase; thiolase: 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase; apo C-III: apolipoprotein C-III. Adapted from [23].

Fenofibrate reportably acts as a weight-stabilizer through PPARα although these results were obtained using male animal models [9–11, 22]. Nevertheless, these reports suggest that fenofibrate not only prevents excessive weight gain but is also able to mobilize fat from adipose tissue by increasing fat catabolism in the liver. Notably, reductions in body weight gain and WAT mass by fenofibrate were similar in male and female OVX mice but were absent in female Sham mice.

Fenofibrate seems to differentially affect body weight and adiposity among OVX and Sham mice by a mechanism other than the modulation of leptin gene expression. Although leptin is produced only in adipose tissue and elicits satiety responses by binding to leptin receptors in the brain [89, 90], changes in leptin mRNA levels are in accordance with those in body weight and WAT mass in both female OVX and Sham mice following fenofibrate treatment. Consistent with this finding, Guerre-Millo et al. [10] reported that serum leptin concentrations positively correlated with body weight and epididymal adipose tissue mass in fenofibrate-treated male mice [10], suggesting that fenofibrate modulates body weight, not by influencing leptin gene expression and food intake, but by enhancing energy expenditure [91, 92].

Differences in PPARα target gene expression seem to explain the different effects of fenofibrate on gonad-dependent weight gain in females (Figure 5(b)). Fenofibrate not only elevated the transcriptional activation of PPARα target genes, ACOX, HD, and thiolase but also reduced apo C-III mRNA levels compared to a high fat diet alone in both groups of mice. Moreover, these alterations in expression levels were found to be more prominent in female OVX mice than in Sham mice after fenofibrate treatment. Thus, fenofibrate influences obesity via the differential activation of PPARα.

It has also been reported that ovarian steroids can affect obesity and lipid metabolism and that these effects are likely mediated by estrogens [12]. E2 insufficiency is thought to be largely responsible for increased adiposity and circulating lipids in OVX rodents because such animals do not display obesity, adiposity, and lipid disorders when they are administered E2 replacement [17–19]. Although the administration of E2 or fenofibrate alone effectively reduces body weight gain and WAT mass in high fat diet-fed female OVX mice, fenofibrate treatment does not prevent them in female Sham mice with functioning ovaries. These results suggest the possibility that signal cross-talk may exist between PPARα and ERs in their effects on obesity and that the action of fenofibrate may be influenced by estrogens in females [25, 27, 93].

In conclusion, treatment with fenofibrate has different effects on body weight and WAT mass due in part to differentially activating hepatic β-oxidation and apo C-III gene expression between female Sham and OVX mice. These differences may provide important information about the mechanisms modulating obesity and about the actions of other lipid lowering drugs, such as fenofibrate, which are PPARα ligands in females.

3.4. The Actions of PPARα on Obesity Are Inhibited by Estrogens

My previous results show that the PPARα ligand fenofibrate reduced body weight gain and adiposity in male and female OVX mice, but not in female mice with functioning ovaries [20–23], suggesting that the actions of fenofibrate on obesity are influenced by E2.

E2 affects the ability of fenofibrate to reduce body weight gain and adiposity in female OVX mice. Mice fed a high fat diet with either fenofibrate or E2 for 13 weeks exhibited significant decreases in body weight gain and WAT mass compared to high fat diet-fed controls. These observations are supported by my previous results showing that fenofibrate stimulates hepatic FA β-oxidation in female OVX mice [21, 23], as well as by other reports showing that E2 inhibits feeding by decreasing meal size in OVX animals [94, 95]. However, these reductions were not enhanced when mice were concomitantly treated with fenofibrate and E2, indicating that E2 may inhibit the function of PPARα in female obesity [32]. Evidence from both humans and laboratory animals show that E2 plays an important role in regulating body weight and WAT mass. Ovariectomy in rodents increases WAT mass, and E2 replacement decreases WAT mass [94]. Similarly, while postmenopausal women have increased body weight gain and WAT weight, E2 decreases both of these [96, 97]. Other studies have also suggested that fenofibrate reduces body weight gain in male animal models [9–11] but does not induce decreases in body weight and WAT mass gains in female mice [20, 21, 23], suggesting that E2 may inhibit the actions of fenofibrate on body weight and WAT mass in female OVX mice.

Similarly, the combination of E2 and fenofibrate did not result in any additional beneficial effects on lipid metabolism in female OVX mice. While serum levels of total cholesterol and triglycerides were lowered in mice fed a high fat diet with either fenofibrate or E2 compared with mice fed a high fat diet alone [9, 18], the combination of E2 and fenofibrate increased levels of circulating total cholesterol and triglycerides compared with either E2 or fenofibrate alone. These results are in agreement with findings that the combination of a lipid-lowering fibrate and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for 3 months not only had no additional benefits on the routine serum lipid or lipoprotein profiles in overweight postmenopausal women with elevated triglycerides but also increased serum triglycerides [97]. Consistent with the circulating lipid metabolism, the fenofibrate-induced decrease in hepatic lipid accumulation was also increased by E2 in female OVX mice. Mice fed a high fat diet showed considerable hepatic lipid accumulation, which was prevented by fenofibrate or E2. In contrast, mice concomitantly treated with fenofibrate and E2 showed an accumulation of triglyceride droplets. Thus, it appears that E2 inhibits fenofibrate-induced increases in fat catabolism in the liver of female OVX mice. Fenofibrate-treated OVX mice were found to have similar food intake to Sham controls whereas OVX mice given E2 showed decreased food intake. However, a combinational treatment of fenofibrate and E2 increased body weight gain, fat weight, and hepatic fat accumulation compared with fenofibrate alone, despite similar food consumption profiles between E2 and fenofibrate plus E2 groups, suggesting that E2 may affect the ability of fenofibrate to regulate energy balance.

Fenofibrate-activated PPARα has been shown to regulate the expression of a number of genes critical for FA β-oxidation and lipid catabolism. Fenofibrate upregulated ACOX, HD, and thiolase mRNA levels whereas E2 downregulated the transcriptional activation of these genes. Coadministration of fenofibrate and E2 significantly decreased ACOX, HD, and thiolase mRNA levels compared with fenofibrate treatment. These results were in accordance with serum levels of triglycerides and total cholesterol as well as body weight and WAT mass. Thus, inhibition of the actions of PPARα on body weight, WAT mass, and circulating lipid levels by E2 may be attributed, in part, to reductions in hepatic mRNA expression of PPARα-mediated peroxisomal FA β-oxidizing enzymes by E2.

Consistent with the in vivo data, E2 inhibited basal PPARα reporter gene activity as well as Wy14,643-induced reporter gene activation in NMu2Li murine liver cells transfected with PPARα, showing that E2 can modulate PPARα transactivation (Figure 6(a)). The inhibitory activity by E2 is mediated through its binding to endogenous ERs that are normally expressed in NMu2Li liver cells since it is reported that E2 does not bind directly PPARs [98]. However, the possibility that E2 directly binds to PPARα and inhibits PPARα function cannot be excluded, because no binding studies have been performed. In cells transfected with either ERα or ERβ, ERs inhibited the basal expression of PPRE-mediated reporter gene activity (Figure 6(b)). These inhibitory effects were significantly increased by E2 treatment. This is supported by results showing that PPARs can regulate ER target gene expression and that signal cross-talk between ERs and PPARs has been reported to be bidirectional [24–26, 28, 93].

Figure 6.

Inhibition of PPARα reporter gene expression ((a) and (b)) and coactivator recruitment (c) by 17 β -estradiol. (a) NMu2Li cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids for PPARα and PPRE3-TK-Luc reporter. * Significantly different versus control group, P < .0001. #: Significantly different versus PPARα group P < .0001. @ Significantly different versus PPARα/Wy group, P < .001. (b) NMu2Li cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids for PPRE3-TK-Luc reporter and ERα or ERβ.∗: Significantly different versus control group, P < .05.#: Significantly different versus respective ER group, P < .01. (c) CV-1 cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids for VP16-mPPARα, GAL-CBP, reporter plasmid pFR-Luc, and VP16-hERα or VP16-hERβ. #: Significantly different versus PPARα group, P < .01.∗: Significantly different versus PPARα/Wy group, P < .005. Adapted from [32].

Mechanistic studies revealed that the E2-ER complex was not likely to be competent for PPARα transactivation, as indicated by the inability of E2 to stimulate PPARα recruitment of coactivators such as CBP (Figure 6(c)). Ligand-induced conformational changes that allow recruitment of coactivators, such as CBP and the dissociation of corepressors such as NCoR, are obligatory for transactivation by PPARα. Treatment of transfected CV-1 cells with Wy14,643 caused efficient CBP recruitment as evidenced by an increase in luciferase reporter gene activity. However, E2 significantly decreased Wy14,643-induced CBP association in the presence of ERα or ERβ. Thus, inhibition of PPARα transactivation by ERs was due to competition for coactivators, increased availability of corepressors, or some other mechanism. [26, 28] It has previously been shown that competition of distinct nuclear receptor for coactivator binding results in a negative cross-talk between nuclear receptors [99, 100]. These results suggest that E2 inhibition of PPARα function occurs by impairing the recruitment of transcriptional coactivators.

PPARα and ERs bind to short DNA sequences termed HREs, ERE for ERs and PPRE for PPARα [54, 101]. An ERE is an inverted repeat containing three intervening bases (AGGTCA N3 TGACCT) whereas a PPRE is a direct repeat with one or two intervening sequences (AGGTCA N1,2 AGGTCA). Nonetheless, these sequences contain an AGGTCA half site, which could be recognized by either ERs or PPARα. Signal cross-talk between PPAR/RXR and ERs has been reported to occur through competitive binding to ERE [24]. Therefore, the inhibition of PPARα transactivation by ERs may also have been due to their competition for PPRE.

In conclusion, in vivo and in vitro studies demonstrate that E2 inhibits the actions of PPARα on obesity through its effects on hepatic PPARα -dependent regulation of target genes and that these processes are mediated by inhibition of PPARα recruitment of coactivators by E2-activated ERs (Figure 7). PPARα ligands fibrates may act as efficient weight controllers under estrogen-free conditions. Although E2 alone decreases body weight gain and WAT mass, E2 may impair PPARα actions on obesity. Thus, these results provide a rationale for the use of fenofibrate in men and postmenopausal women with obesity and lipid disorder, but not for premenopausal women with functioning ovaries.

Figure 7.

Mechanism of inhibitory effect of 17β-estradiol on PPAR α -mediated regulation of obesity. (a) Competition between PPARα and estrogen receptors (ERs) for coactivator binding. 17β-estradiol-activated ERs can interfere with the PPRE binding of PPARα. (b) Inhibition of PPARα actions on obesity by E. E impairs the ability of PPARα ligands to reduce body weight gain and adiposity in female ovariectomized (OVX) mice. FF: fenofibrate; RA: 9 cis-retinoic acid; RXR: retinoid X receptor. Adapted from [33].

4. Conclusion

Obesity is the leading cause of the metabolic diseases including type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis, and hypertension. PPARα has been the subject of intense academic and pharmaceutical research because of its ability to improve obesity-related metabolic disorders. The PPARα ligand fenofibrate seems to exhibit an antiobesity effect through FA β-oxidation in animal models although such an effect of PPARα activators has not yet been reported in humans. However, this idea is supported by several human studies showing that obese patients with impaired fat oxidation failed to lose weight, suggesting that elevated fat oxidation leads to weight loss. Interestingly, there is a sex difference in the control of obesity by fenofibrate. Fenofibrate regulates body weight and adiposity with sexual dimorphism in nutritionally induced obese male mice. Moreover, fenofibrate-induced reductions in body weight gain and WAT mass in male mice were also shown by female OVX mice, but these effects were absent in female Sham mice, suggesting the involvement of ovarian hormones in the differential regulation of obesity among these groups. In OVX mice, E2 inhibited the actions of fenofibrate-activated PPARα on obesity, due in part to reductions in hepatic expression of PPARα-mediated FA β-oxidizing enzymes by E2, a process mediated through the inhibition of PPARα coactivator recruitment by E2. These results provide a mechanism to explain why fenofibrate reduces body weight gain and adiposity in males and OVX female mice but does not regulate obesity in female mice with functioning ovaries.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by Mid-career Researcher Program (no. 2009-0083990) and Female Scientist Program (no. 2010-0017313) through NRF Grant funded by the MEST.

References

- 1.Issemann I, Green S. Activation of a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily by peroxisome proliferators. Nature. 1990;347(6294):645–650. doi: 10.1038/347645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck F, Plummer S, Senior PV, Byrne S, Green S, Brammar WJ. The ontogeny of peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor gene expression in the mouse and rat. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 1992;247(1319):83–87. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1992.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braissant O, Foufelle F, Scotto C, Dauça M, Wahli W. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): tissue distribution of PPAR-α, -β, and -γ in the adult rat. Endocrinology. 1996;137(1):354–366. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.1.8536636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoyama T, Peters JM, Iritani N, et al. Altered constitutive expression of fatty acid-metabolizing enzymes in mice lacking the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(10):5678–5684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auwerx J, Schoonjans K, Fruchart J-C, Staels B. Transcriptional control of triglyceride metabolism: fibrates and fatty acids change the expression of the LPL and apo C-III genes by activating the nuclear receptor PPAR. Atherosclerosis. 1996;124, supplement:S29–S37. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(96)05854-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hertz R, Bishara-Shieban J, Bar-Tana J. Mode of action of peroxisome proliferators as hypolipidemic drugs. Suppression of apolipoprotein C-III. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(22):13470–13475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan ZH, Karam WG, Staudinger JL, Medvedev A, Ghanayem BI, Jetten AM. Regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α-induced transactivation by the nuclear orphan receptor TAK1/TR4. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(18):10948–10957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.10948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costet P, Legendre C, Moré J, Edgar A, Galtier P, Pineau T. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α-isoform deficiency leads to progressive dyslipidemia with sexually dimorphic obesity and steatosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(45):29577–29585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaput E, Saladin R, Silvestre M, Edgar AD. Fenofibrate and rosiglitazone lower serum triglycerides with opposing effects on body weight. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2000;271(2):445–450. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerre-Millo M, Gervois P, Raspé E, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α activators improve insulin sensitivity and reduce adiposity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(22):16638–16642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.22.16638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mancini FP, Lanni A, Sabatino L, et al. Fenofibrate prevents and reduces body weight gain and adiposity in diet-induced obese rats. FEBS Letters. 2001;491(1-2):154–158. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mystkowski P, Schwartz MW. Gonadal steroids and energy homeostasis in the leptin era. Nutrition. 2000;16(10):937–946. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00458-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wade GN. Some effects of ovarian hormones on food intake and body weight in female rats. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1975;88(1):183–193. doi: 10.1037/h0076186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tchernof A, Calles-Escandon J, Sites CK, Poehlman ET. Menopause, central body fatness, and insulin resistance: effects of hormone-replacement therapy. Coronary Artery Disease. 1998;9(8):503–511. doi: 10.1097/00019501-199809080-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geary N, Asarian L. Estradiol increases glucagon’s satiating potency in ovariectomized rats. American Journal of Physiology. 2001;281(4):R1290–R1294. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.4.R1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D’Eon TM, Souza SC, Aronovitz M, Obin MS, Fried SK, Greenberg AS. Estrogen regulation of adiposity and fuel partitioning: evidence of genomic and non-genomic regulation of lipogenic and oxidative pathways. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(43):35983–35991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shearer GC, Joles JA, Jones H, Jr., Walzem RL, Kaysen GA. Estrogen effects on triglyceride metabolism in analbuminemic rats. Kidney International. 2000;57(6):2268–2274. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shinoda M, Latour MG, Lavoie J-M. Effects of physical training on body composition and organ weights in ovariectomized and hyperestrogenic rats. International Journal of Obesity. 2002;26(3):335–343. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roesch DM. Effects of selective estrogen receptor agonists on food intake and body weight gain in rats. Physiology & Behavior. 2006;87(1):39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoon M, Jeong S, Nicol CJ, et al. Fenofibrate regulates obesity and lipid metabolism with sexual dimorphism. Experimental and Molecular Medicine. 2002;34(6):481–488. doi: 10.1038/emm.2002.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoon M, Jeong S, Lee H, et al. Fenofibrate improves lipid metabolism and obesity in ovariectomized LDL receptor-null mice. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2003;302(1):29–34. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeong S, Kim M, Han M, et al. Fenofibrate prevents obesity and hypertriglyceridemia in low-ddensity lipoprotein receptor-null mice. Metabolism. 2004;53(5):607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeong S, Han M, Lee H, et al. Effects of fenofibrate on high-fat diet-induced body weight gain and adiposity in female C57BL/6J mice. Metabolism. 2004;53(10):1284–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keller H, Givel F, Perroud M, Wahli W. Signaling cross-talk between peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor/retinoid X receptor and estrogen receptor through estrogen response elements. Molecular Endocrinology. 1995;9(7):794–804. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.7.7476963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nunez SB, Medin JA, Keller H, Ozato K, Wahli W, Segars J. Retinoid X receptor β and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor activate an estrogen response element. Recent Progress in Hormone Research. 1995;50(1):409–415. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571150-0.50029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu Y, Kan L, Qi C, et al. Isolation and characterization of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) interacting protein (PRIP) as a coactivator for PPAR. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(18):13510–13516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nuñez SB, Medin JA, Braissant O, et al. Retinoid X receptor and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor activate an estrogen responsive gene independent of the estrogen receptor. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 1997;127(1):27–40. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(96)03980-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tcherepanova I, Puigserver P, Norris JD, Spiegelman BM, McDonnell DP. Modulation of estrogen receptor-α transcriptional activity by the coactivator PGC-1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(21):16302–16308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001364200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boitier E, Gautier J-C, Roberts R. Advances in understanding the regulation of apoptosis and mitosis by peroxisome-proliferator activated receptors in pre-clinical models: relevance for human health and disease. Comparative Hepatology. 2003;2, article 3 doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wierman ME. Sex steroid effects at target tissues: mechanisms of action. Advances in Physiology Education. 2007;31(1):26–33. doi: 10.1152/advan.00086.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bain DL, Heneghan AF, Connaghan-Jones KD, Miura MT. Nuclear receptor structure: implications for function. Annual Review of Physiology. 2007;69:201–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.031905.160308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeong S, Yoon M. Inhibition of the actions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor a on obesity by estrogen. Obesity. 2007;15(6):1430–1440. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoon M. The role of PPARα in lipid metabolism and obesity: focusing on the effects of estrogen on PPARα actions. Pharmacological Research. 2009;60:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jenster G. Coactivators and corepressors as mediators of nuclear receptor function: an update. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 1998;143(1-2):1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glass CK. Going nuclear in metabolic and cardiovascular disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116(3):556–560. doi: 10.1172/JCI27913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flamant F, Gauthier K, Samarut J. Thyroid hormones signaling is getting more complex: STORMs are coming. Molecular Endocrinology. 2007;21(2):321–333. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arpino G, Wiechmann L, Osborne CK, Schiff R. Crosstalk between the estrogen receptor and the HER tyrosine kinase receptor family: molecular mechanism and clinical implications for endocrine therapy resistance. Endocrine Reviews. 2008;29(2):217–233. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sher T, Yi H-F, McBride OW, Gonzalez FJ. cDNA cloning, chromosomal mapping, and functional characterization of the human peroxisome proliferator activated receptor. Biochemistry. 1993;32(21):5598–5604. doi: 10.1021/bi00072a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marx N, Duez H, Fruchart J-C, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and atherogenesis: regulators of gene expression in vascular cells. Circulation Research. 2004;94(9):1168–1178. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000127122.22685.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Staels B, Koenig W, Habib A, et al. Activation of human aortic smooth-muscle cells is inhibited by PPARα but not by PPARγ activators. Nature. 1998;393(6687):790–793. doi: 10.1038/31701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krey G, Braissant O, L’Horset F, et al. Fatty acids, eicosanoids, and hypolipidemic agents identified as ligands of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors by coactivator-dependent receptor ligand assay. Molecular Endocrinology. 1997;11(6):779–791. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.6.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berger JP, Akiyama TE, Meinke PT. PPARs: therapeutic targets for metabolic disease. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2005;26(5):244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fiévet C, Fruchart J-C, Staels B. PPARα and PPARγ dual agonists for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2006;6(6):606–614. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Srivastava RAK, Jahagirdar R, Azhar S, Sharma S, Bisgaier CL. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α selective ligand reduces adiposity, improves insulin sensitivity and inhibits atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2006;285(1-2):35–50. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-9053-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang S, Subramaniam A, Cawthorne MA, Clapham JC. Increased fatty acid oxidation in transgenic mice overexpressing UCP3 in skeletal muscle. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2003;5(5):295–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2003.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cabrero À, Alegret M, Sánchez RM, Adzet T, Laguna JC, Vázquez M. Bezafibrate reduces mRNA levels of adipocyte markers and increases fatty acid oxidation in primary culture of adipocytes. Diabetes. 2001;50(8):1883–1890. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Okamoto Y, Higashiyama H, Inoue H, Kanematsu M, Kinoshita M, Asano S. Quantitative image analysis in adipose tissue using an automated image analysis system: differential effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α and -γ agonist on white and brown adipose tissue morphology in AKR obese and db/db diabetic mice. Pathology International. 2007;57(6):369–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2007.02109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jeong S, Yoon M. Fenofibrate inhibits adipocyte hypertrophy and insulin resistance by activating adipose PPARα in high fat diet-induced obese mice. Experimental and Molecular Medicine. 2009;41(6):397–405. doi: 10.3858/emm.2009.41.6.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muoio DM, Dohm GL. Peripheral metabolic actions of leptin. Best Practice & Research: Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2002;16(4):653–666. doi: 10.1053/beem.2002.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hines EP, White SS, Stanko JP, Gibbs-Flournoy EA, Lau C, Fenton SE. Phenotypic dichotomy following developmental exposure to perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in female CD-1 mice: low doses induce elevated serum leptin and insulin, and overweight in mid-life. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2009;304(1-2):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koh EH, Kim M-S, Park J-Y, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-α activation prevents diabetes in OLETF rats: comparison with PPAR-γ activation. Diabetes. 2003;52(9):2331–2337. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.9.2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lalloyer F, Vandewalle B, Percevault F, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α improves pancreatic adaptation to insulin resistance in obese mice and reduces lipotoxicity in human islets. Diabetes. 2006;55(6):1605–1613. doi: 10.2337/db06-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Staels B, Maes M, Zambon A. Fibrates and future PPARα agonists in the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Nature Clinical Practice Cardiovascular Medicine. 2008;5(9):542–553. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klein-Hitpass L, Schorpp M, Wagner U, Ryffel GU. An estrogen-responsive element derived from the 5’ flanking region of the Xenopus vitellogenin A2 gene functions in transfected human cells. Cell. 1986;46(7):1053–1061. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90705-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hall JM, McDonnel DP. The estrogen receptor β-isoform (ERβ) of the human estrogen receptor modulates ERα transcriptional activity and is a key regulator of the cellular response to estrogens and antiestrogens. Endocrinology. 1999;140(12):5566–5578. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Katzenellenbogen BS. Estrogen receptors: bioactivities and interactions with cell signaling pathways. Biology of Reproduction. 1996;54(2):287–293. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod54.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dieudonné MN, Leneveu MC, Giudicelli Y, Pecquery R. Evidence for functional estrogen receptors α and β in human adipose cells: regional specificities and regulation by estrogens. American Journal of Physiology. 2004;286(3):C655–C661. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00321.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barros RPA, Machado UF, Warner M, Gustafsson J-Å. Muscle GLUT4 regulation by estrogen receptors ERβ and ERα . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(5):1605–1608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510391103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koehler KF, Helguero LA, Haldosén L-A, Warner M, Gustafsson J-Å. Reflections on the discovery and significance of estrogen receptor β . Endocrine Reviews. 2005;26(3):465–478. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wiik A, Glenmark B, Ekman M, et al. Oestrogen receptor β is expressed in adult human skeletal muscle both at the mRNA and protein level. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 2003;179(4):381–387. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-6772.2003.01186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nilsson S, Mäkelä S, Treuter E, et al. Mechanisms of estrogen action. Physiological Reviews. 2001;81(4):1535–1565. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bouchard C, Després J-P, Mauriège P. Genetic and nongenetic determinants of regional fat distribution. Endocrine Reviews. 1993;14(1):72–93. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-1-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sharp JC, Copps JC, Liu Q, et al. Analysis of ovariectomy and estrogen effects on body composition in rats by X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging techniques. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2000;15(1):138–146. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.1.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gray JM, Wade GN. Food intake, body weight, and adiposity in female rats: actions and interactions of progestins and antiestrogens. American Journal of Physiology. 1981;240(5):E474–E481. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1981.240.5.E474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leshner A, Collier G. The effects of gonadectomy on the sex differences in dietary self selection patterns and carcass compositions of rats. Physiology & Behavior. 1973;11(5):671–676. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(73)90253-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jones MEE, Thorburn AW, Britt KL, et al. Aromatase-deficient (ArKO) mice have a phenotype of increased adiposity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(23):12735–12740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heine PA, Taylor JA, Iwamoto GA, Lubahn DB, Cooke PS. Increased adipose tissue in male and female estrogen receptor-α knockout mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(23):12729–12734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Houpt KA, Coren B, Hintz HF, Hilderbrant JE. Effect of sex and reproductive status on sucrose preference, food intake, and body weight of dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1979;174(10):1083–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rosenblatt H, Dyrenfurth I, Ferin M, vande Wiele RL. Food intake and the menstrual cycle in rhesus monkeys. Physiology & Behavior. 1980;24(3):447–449. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(80)90234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Geary N, Asarian L. Cyclic estradiol treatment normalizes body weight and test meal size in ovariectomized rats. Physiology & Behavior. 1999;67(1):141–147. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(99)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liang Y-Q, Akishita M, Kim S, et al. Estrogen receptor β is involved in the anorectic action of estrogen. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 2002;26(8):1103–1109. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gasse C, Hense H-W, Stieber J, Döring A, Liese AD, Keil U. Assessing hypertension management in the community: trends of prevalence, detection, treatment, and control of hypertension in the MONICA Project, Augsburg 1984–1995. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2001;15(1):27–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barros RPA, Machado UF, Gustafsson J-A. Estrogen receptors: new players in diabetes mellitus. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2006;12(9):425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Lehmkuhl E, Mahmoodzadeh S. Gender aspects of the role of the metabolic syndrome as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Gender Medicine. 2007;4(supplement B):S162–S177. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(07)80056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shi H, Clegg DJ. Sex differences in the regulation of body weight. Physiology & Behavior. 2009;97:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fruchart JC, Brewer HB, Jr., Leitersdorf E, et al. Consensus for the use of fibrates in the treatment of dyslipoproteinemia and coronary heart disease. American Journal of Cardiology. 1998;81(7):912–917. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lupien PJ, Brun D, Gagne C, Moorjani S, Bielman P, Julien P. Gemfibrozil therapy in primary type II hyperlipoproteinemia: effects on lipids, lipoproteins and apolipoproteins. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 1991;7(1):27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rustan AC, Christiansen EN, Drevon CA. Serum lipids, hepatic glycerolipid metabolism and peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation in rats fed ω-3 and ω-6 fatty acids. Biochemical Journal. 1992;283(2):333–339. doi: 10.1042/bj2830333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Skrede S, Bremer J, Berge RK, Rustan AC. Stimulation of fatty acid oxidation by a 3-thia fatty acid reduces triacylglycerol secretion in cultured rat hepatocytes. Journal of Lipid Research. 1994;35(8):1395–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Akiyama TE, Nicol CJ, Fievet C, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α regulates lipid homeostasis, but is not associated with obesity. Studies with congenic mouse lines. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(42):39088–39093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107073200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schreyer SA, Vick C, Lystig TC, Mystkowski P, LeBoeuf RC. LDL receptor but not apolipoprotein E deficiency increases diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. American Journal of Physiology. 2002;282:E207–E214. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2002.282.1.E207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lake BG. Mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenicity of peroxisome-proliferating drugs and chemicals. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 1995;35:483–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.002411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Minnich A, Tian N, Byan L, Bilder G. A potent PPARα agonist stimulates mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation in liver and skeletal muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 2001;280(2):E270–E279. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.2.E270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Taghibiglou C, Carpentier A, Van Iderstine SC, et al. Mechanisms of hepatic very low density lipoprotein overproduction in insulin resistance. Evidence for enhanced lipoprotein assembly, reduced intracellular ApoB degradation, and increased microsomal triglyceride transfer protein in a fructose-fed hamster model. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(12):8416–8425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Siri P, Candela N, Zhang Y-L, et al. Post-transcriptional stimulation of the assembly and secretion of triglyceride-rich apolipoprotein B lipoproteins in a mouse with selective deficiency of brown adipose tissue, obesity, and insulin resistance. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(49):46064–46072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shimizugawa T, Ono M, Shimamura M, et al. ANGPTL3 decreases very low density lipoprotein triglyceride clearance by inhibition of lipoprotein lipase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(37):33742–33748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203215200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Peters JM, Hennuyer N, Staels B, et al. Alterations in lipoprotein metabolism in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α-deficient mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(43):27307–27312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Staels B, Vu-Dac N, Kosykh VA, et al. Fibrates downregulate apolipoprotein C-III expression independent of induction of peroxisomal acyl coenzyme A oxidase. A potential mechanism for the hypolipidemic action of fibrates. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1995;95(2):705–712. doi: 10.1172/JCI117717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994;372(6505):425–432. doi: 10.1038/372425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lee G-H, Proenca R, Montez JM, et al. Abnormal splicing of the leptin receptor in diabetic mice. Nature. 1996;379(6566):632–635. doi: 10.1038/379632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kelly LJ, Vicario PP, Thompson GM, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors γ and α mediate in vivo regulation of uncoupling protein (UCP-1, UCP-2, UCP-3) gene expression. Endocrinology. 1998;139(12):4920–4927. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.12.6384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, Takahashi M, Kim H, Ezaki O. Up-regulation of liver uncoupling protein-2 mRNA by either fish oil feeding or fibrate administration in mice. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1999;257(3):879–885. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang X, Kilgore MW. Signal cross-talk between estrogen receptor alpha and beta and the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma1 in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2002;194(1-2):123–133. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wade GN, Gray JM, Bartness TJ. Gonadal influences on adiposity. International Journal of Obesity. 1985;9(1):83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Asarian L, Geary N. Modulation of appetite by gonadal steroid hormones. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B. 2006;361(1471):1251–1263. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tchernof A, Calles-Escandon J, Sites CK, Poehlman ET. Menopause, central body fatness, and insulin resistance: effects of hormone-replacement therapy. Coronary Artery Disease. 1998;9(8):503–511. doi: 10.1097/00019501-199809080-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nerbrand C, Nyberg P, Nordström L, Samsioe G. Effects of a lipid lowering fibrate and hormone replacement therapy on serum lipids and lipoproteins in overweight postmenopausal women with elevated triglycerides. Maturitas. 2002;42(1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(01)00302-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ma H, Sprecher HW, Kolattukudy PE. Estrogen-induced production of a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) ligand in a PPARγ-expressing tissue. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(46):30131–30138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lopez GN, Webb P, Shinsako JH, Baxter JD, Greene GL, Kushner PJ. Titration by estrogen receptor activation function-2 of targets that are downstream from coactivators. Molecular Endocrinology. 1999;13(6):897–909. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.6.0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Foryst-Ludwig A, Clemenz M, Hohmann S, et al. Metabolic actions of estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) are mediated by a negative cross-talk with PPARγ . PLoS Genetics. 2008;4(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000108. Article ID e1000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tugwood JD, Issemann I, Anderson RG, Bundell KR, McPheat WL, Green S. The mouse peroxisome proliferator activated receptor recognizes a response element in the 5’ flanking sequence of the rat acyl CoA oxidase gene. The EMBO Journal. 1992;11(2):433–439. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]