Abstract

To document the behavior of tobacco manufacturers’ agricultural third-party allies in South Carolina from the 1970s through 2009, we analyzed news reports, public documents and internal tobacco industry documents and conducted interviews with knowledgeable individuals. We found that agriculture-based interest groups (the Farm Bureau), elected state agency heads (Commissioners of Agriculture) and tobacco-area legislators acted as an iron triangle containing strong third-party allies of tobacco manufacturers from the 1970s through the 1990s. The Farm Bureau and Commissioners of Agriculture reacted to national-level changes in the tobacco leaf market structure by shifting towards a neutral position on tobacco control, while some tobacco-area legislators remained manufacturer allies (Sullivan et al, 2009). This shift was reinforced by public health outreach and successes, which were in turn facilitated by the lack of opposition from agricultural groups. We conclude that public health advocates in tobacco-growing states should use the pragmatic shift of agricultural groups’ position to challenge remaining third-party manufacturer alliances and agriculture-based opposition to tobacco control policies.

Keywords: tobacco control, Southern United States, politics, tobacco farming, social norms, smoking restrictions, USA

Tobacco-growing states have higher tobacco use and greater tobacco-induced disease than other states (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & Promotion, 2008; Crankshaw, Beach, Austin, Weitzenkamp, Anderson, Altman et al., 2009). They tend to have low cigarette taxes, few clean indoor air laws and low funding for tobacco use prevention programming (Chaloupka, Hahn, & Emery, 2002; Crankshaw et al., 2009), policies that reduce smoking (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000) and health costs (Lightwood, Dinno, & Glantz, 2008).

Tobacco manufacturers have historically used third-party allies to influence state policy processes (Campbell & Balbach, 2008; Dearlove, Bialous, & Glantz, 2002; M. S. Givel & Glantz, 2001; Mandel & Glantz, 2004; Ritch & Begay, 2001). In tobacco producing states, manufacturers recruited agricultural allies from the arms that comprised the iron triangle that controlled tobacco policymaking: agriculture interest groups, state agriculture agencies and tobacco-area state legislators. An “iron triangle” is a closed, stable policymaking community focused on a specific issue area composed of related interest groups, bureaucrats and key committee legislators, each with an economic interest in the issue (Heclo, 1978; Jordan, 1981; Miroff, Seidelman, & Swanstron, 1998; Yishai, 1992). Within an iron triangle, interest groups lobby key legislators and bureaucrats, while bureaucrats administer programs with interest group input and provide support to constituents of key legislators, and legislators push legislation favorable to the interest groups and provide budgets and political support for bureaucrats (M. Givel & Glantz, 2000).

In many policy areas, iron triangles have given way to “issue networks” (Skok, 1995), more fluid policymaking communities based more on knowledge of the issue area than power, due to the entrance of new stakeholders and perspectives (Golden, 1998; Heclo, 1978; Jordan, 1981; Skok, 1995; Wilson, 2005). In an issue network the concept of expertise and power on a topic is broader and more policy specialists and interests are able to influence the policy-making process. Both models are usually applied to the federal level, but some have applied the iron triangle model to states (Browne, 1987), particularly around tobacco control (M. Givel & Glantz, 2000; Michael Givel & Glantz, 2004a;M. S. Givel & Glantz, 2001).

Beginning in the 1970s, cigarette manufacturers effectively utilized the state agriculture-based iron triangle to prevent significant progress in tobacco control policy by convincing key entities in each arm of the triangle that their interests overlapped with those of the manufacturers. However, between 1997 and 2007 the manufacturer-agriculture alliance began to disintegrate as the agriculture interests began to realize that their interests were no longer congruent with the manufacturers, primarily due to a decline in demand for US tobacco leaf by cigarette manufacturers and national changes in the tobacco market structure.

South Carolina offers a unique opportunity to study the political ramifications of the changing tobacco agriculture-manufacturer relationship. The state never had manufacturing facilities, eliminating the political effects of an in-state manufacturing interest. South Carolina’s tobacco crop was the fifth largest in the US in 2008 in value ($69 million) and acreage (19,000 acres), behind North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia (United States Department of Agriculture, 2009b). Tobacco growing in South Carolina was historically focused in the 11-county “Pee Dee” region; in 2007 significant amounts of tobacco were grown in only six of those counties, with over 1/3 of the state’s total tobacco crop produced in Horry County (United States Department of Agriculture, 2009a).

The political distancing of agricultural allies from their former manufacturing allies provides an opening for tobacco control advocacy. State agricultural interests reacted to national-level events by shifting from staunch advocacy for manufacturer positions on tobacco control towards neutral positions to better represent their farming constituency’s interests. While some tobacco-area legislators in South Carolina remained anti-tobacco control (Sullivan et al, 2009), since the late 1990s the Farm Bureau and Commissioners of Agriculture moved from strong opposition towards neutrality or support. The lack of opposition from these groups facilitated successes by the state’s developing public health infrastructure, as the iron triangle opened into an issue network including the public health groups. The South Carolina example of decreased political opposition to tobacco control represents an opportunity for stronger tobacco control policies in tobacco-growing states.

METHODS

We analyzed news reports, public documents, internal tobacco industry documents (accessed through http://www.legacy.library.ucsf.edu and http://www.tobaccodocuments.org). We also conducted 58 unstructured, comprehensive, recorded and transcribed interviews with 36 individuals, including 8 national tobacco control experts, 25 South Carolina tobacco control advocates and 3 representatives of South Carolina agricultural interests between January 2008 and June 2009 (Sullivan, Barnes, & Glantz, 2009). We requested interviews with lobbyists for manufacturers, but were declined. All 58 interviews were used to prepare this paper; the six quoted in this paper represent the range of viewpoints that were expressed. We sought to interview people named in the written record and tobacco documents; each interviewee was asked who else we should interview in accordance with standard snowball technique. Interviews were conducted in accordance with a protocol approved by the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research.

RESULTS

Historical Alliance

For much of the 1900s, tobacco was among the top crops produced in South Carolina (United States Department of Agriculture, 2009a). In this environment, manufacturers directly lobbied to oppose tobacco control policies (Sullivan et al., 2009), but needed a genuine local constituency to strengthen their position with local politicians. Agriculture provided the ideal third-party ally in South Carolina. State agricultural interests acted as a preexisting iron triangle around tobacco farming policy in the late 1970s, independent of the manufacturers. Recognizing their influence on state-level policy, manufacturers targeted each arm of the triangle to engage them as allies to influence tobacco control policy. For example, when the Tobacco Institute, tobacco manufacturers’ national lobbying and public relations organization, began to implement its grassroots advocacy network, the Tobacco Action Network, in tobacco-growing states in 1980, their first strategic priority was to achieve buy-in from each arm of this iron triangle (Farm Bureau Federations, “state political leaders,” and “state tobacco groups”). In South Carolina, the Tobacco Institute listed the key people to be contacted for that first stage as including the Commissioner of Agriculture (G. Bryan Patrick), “members of the State Legislature from tobacco growing districts,” and President of the SC Farm Bureau Harry Bell ([Author Unknown], 1980).

Manufacturers avoided direct contact with South Carolina farmers, because they feared offending powerful state agricultural organizations ([Author Unknown], 1980). Internal tobacco industry documents also reveal that the relationship between tobacco farmers and tobacco manufacturers was fraught with buyer-seller tensions and that manufacturers understood that individual growers represented a tenuous political ally (Dowdell, 1977; Jones, Austin, Beach, & Altman, 2008). Instead, manufacturers engaged with growers indirectly from the 1970s through the 1990s, forging alliances with the South Carolina Farm Bureau, Commissioners of Agriculture and some tobacco-area legislators.

These entities acted as reliable third-party allies for the manufacturers, facilitating and echoing manufacturers’ political strategies and advancing their interests in the policy process by opposing tobacco control policies.

Interest Group: the Farm Bureau

The South Carolina Farm Bureau, the primary agricultural interest group in South Carolina (South Carolina Farm Bureau, 2009), combined grassroots action with direct lobbying to help manufacturers oppose cigarette tax and clean indoor air proposals throughout the 1980s and 1990s (Sullivan et al., 2009; [Author unknown], 1985). In 1983, the Farm Bureau described itself to legislators as the “largest general farm organization in South Carolina” and had local organizations in every county (Bell, 1983). Manufacturers created ties to the Farm Bureau through shared resources (Bankhead, 1982b). A 1985 Tobacco Institute report indicates that the Farm Bureau relied “heavily” on the Tobacco Institute; the Institute noted, “T. I. economic impact studies on tobacco have been the major issue-related resource requested and used by tobacco area legislators in their efforts to debate anti-tobacco legislation. The Farm Bureau and the Department of Agriculture rely heavily on T. I. for this type of support material as well” ([Author unknown], 1985) There is no evidence of direct tobacco manufacturer or Tobacco Institute payments to the Farm Bureau other than that the Institute’s state representative was a paid member (Bankhead, 1982b). In 1985, the Institute described the Farm Bureau as their “strongest ally in legislative battles at the state, local and federal levels. They are a source for grassroots involvement, with members in every county in the state” ([Author unknown], 1985).

The Farm Bureau often relied on arguments that tobacco control policies would hurt tobacco farmers to sway policymakers. As early as 1972, Harry Bell, Farm Bureau President from 1971 through 1997 (South Carolina Farm Bureau, 2009), argued in the press that a cigarette tax increase would be “grossly unfair” to tobacco growers (United Press International, 1972). Bell helped kill a 1983 tax bill by writing a letter to each member of the South Carolina House of Representatives and sending a legislative report to each of the organization’s 86,000 members to encourage grassroots opposition (Bankhead, 1983a; Bell, 1983; South Carolina Farm Bureau, 1983). The Farm Bureau was instrumental in defeating several state and local clean indoor air bills in the 1980s (Bankhead, 1985). This alliance continued into the early 1990s, with the Farm Bureau echoing manufacturer positions on the 1990 Clean Indoor Air Act (Sullivan et al., 2009) and working to support manufacturers at the national level, such as opposing proposed US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulation of tobacco in 1995 (PR Newswire, 1995).

State Agency: Commissioners of Agriculture

The Commissioner of Agriculture, a publicly-elected office since 1912 (South Carolina Department of Agriculture, 2008a), heads the South Carolina Department of Agriculture, which is responsible for promoting and nurturing South Carolina’s agriculture industry and related businesses (South Carolina Department of Agriculture, 2008b). This office was a consistently strong ally of manufacturers in South Carolina during the tenure of Commissioner D. Leslie Tindal, who was Commissioner for five terms from 1982 to 2002 (South Carolina Department of Agriculture, 2008a). (Immediately after Tindal left office in 2002, his successor openly supported diversification out of tobacco, something that had not happened during Tindal's term.)

The Institute targeted Tindal as an ally even before his tenure began, (Tindal, 1982) at which point Tindal “offered his assistance where needed” to the Tobacco Institute (Bankhead, 1982b). Tindal helped defeat tax increases in 1983 and 1985 by sending letters to legislators and speaking in the media, as well as clean indoor air proposals in 1985 (Bankhead, 1982a; Bankhead, 1983a, b), [when the Institute described him as an “important source of legislative support” ([Author unknown], 1985). In 1985, Tindal was offered a $500 campaign contribution from the Institute (Tobacco Institute, 1986); contributions continued through 1998, Tindal’s last election, when he accepted campaign contributions totaling $3,250 from Philip Morris, RJ Reynolds and Universal Leaf Tobacco (National Institute on Money in State Politics, 2008; Sullivan et al., 2009).

Legislators

Several state legislators from the tobacco-growing Pee Dee region, who often served on key committees for tobacco legislation (Bankhead, 1981; Wheeler & Sneegas, 1992), were some of the manufacturers’ strongest allies from the late-1970s through the 1990s (Sullivan et al., 2009). Key tobacco-area legislators were particularly instrumental in defeating tax increases and defeating, delaying or diluting clean indoor air laws through the 1980s and 1990s ([Author unknown], 1987; Bankhead, 1982b; Bankhead, 1983a; Sullivan et al., 2009). The Institute’s strategy for utilizing tobacco-area legislators as allies included coordinating legislative strategy (Bankhead, 1982a) and requests to write opposition letters to other legislators (Bankhead, 1983c). Several prominent tobacco area legislators promoted manufacturer positions on key tobacco control proposals (Wheeler & Sneegas, 1992; Sullivan et al., 2009), including arguments that tobacco control measures would harm tobacco growers and the state’s economy (Hughes, 1989; Sullivan et al., 2009).

Prominent tobacco-area legislator and farmer from the Pee Dee region (South Carolina General Assembly, 1996), Rep. John “Bubba” Snow (D-Georgetown and Williamsburg Counties) was a strong manufacturer ally in the South Carolina House of Representatives from 1976 to 1994 (Sullivan et al., 2009). According to Tobacco Institute internal documents, [Snow spoke against a 1979 clean indoor air bill (Sullivan et al., 2009; Bankhead, J. 1980), and as Chairman of the House Agriculture Committee helped manufacturers kill tobacco tax increases (Bankhead, 1983a) in the mid-1980s sent to him on proposals by other tobacco-area legislators (Sullivan et al., 2009; Bankhead, 1980).. He played a key role in diluting the 1990 Clean Indoor Air Act for manufacturers, promoting a manufacturer-written replacement bill and negotiating with public health groups to include many exemptions (Sullivan et al., 2009; Wheeler & Sneegas, 1992). Similarly, in 1993 Rep. Tom Rhoad (D-Bamberg), one of the state’s largest tobacco growers, chaired the House Agriculture Committee when it defeated proposals to expand the 1990 Clean Indoor Air Act (Scoppe, 1994).

Changing Alliance Dynamics

Despite their long history of allying with manufacturers, by 2009 the Farm Bureau and Commissioners of Agriculture in South Carolina were no longer the manufacturers’ stalwart third-party allies. Both ceased opposing tobacco control policies, as evidenced by their neutral to positive positions on prominent cigarette tax and clean indoor air proposals from 2005 through 2009, and instead focused on promoting diversification out of tobacco and marketing of general state agriculture. While many factors may have led to this shift, the effects of national-level political developments between manufacturers and growers and public health and agricultural groups undoubtedly contributed to a divergence of agricultural and manufacturer interests.

National Background

The US tobacco leaf market was regulated by a federal tobacco price support and quota program, which included a minimum price for US-grown tobacco, acreage allotments for tobacco quota owners and a manufacturer demand-based annual poundage quota, from 1933 through a federal tobacco quota buyout in 2004 (Austin & Altman, 2000; Brown, Rucker, & Thurman, 2007; Grove, 1975; Jones et al., 2008; Sullivan et al., 2009; Zhang & Husten, 1998). The buyout under the 2004 Tobacco Transition Payment Program ended the federal marketing quota and price support program for tobacco and compensated quota holders, effectively freeing tobacco growing from quota system constraints (Markoe, 2004). This change led to fewer, larger tobacco farms and a sharp rise in the proportion of tobacco grown under direct contracts between individual growers and manufacturers with prices set before production (Austin & Altman, 2000; Beach, Jones, & Tooze, 2008; Boyleston, 2009; Crocker, 2009; Fisher, 2000).

Manufacturers were generally successful throughout the US in mobilizing farmers and agricultural organizations to oppose federal and state cigarette tax increases, FDA regulation of tobacco and other tobacco control policies through the 1990s (D. Altman, Levine, & Howard, 1997; D. G. Altman, Levine, Howard, & Hamilton, 1996; Dowdell, 1977; Jones et al., 2008; Zaccaro & Altman, 2000). Tobacco companies were also successful in blaming the decreasing viability of US tobacco farming on health professionals and tobacco control efforts, rather than on manufacturer practices (i.e., increased purchase of international tobacco, pricing decisions and reduced tobacco quotas) (D. Altman et al., 1997;D. G. Altman et al., 1996; Dowdell, 1977; Jones et al., 2008).

However, leading up to the 2004 buyout, tobacco growers and manufacturers found themselves on opposite sides of a series of policy conflicts, straining the already tense agriculture-manufacturer alliance (Jones et al., 2008). Growers and manufacturers disagreed over buyout proposals beginning in the early 1990s (Grove, 1975; Markoe, 2004; Staff and Wire Reports, 2004; Sullivan et al., 2009), the amount of grower compensation from the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) settling litigation against the tobacco industry brought by 46 state attorneys general (which was less than manufacturers had promised grower organizations in exchange for their political support) (“DeLoach, et al., v. Philip Morris Companies, et al., No. 00-CV-1235,” 2000; Fisher, 2000; M.Givel & Glantz, 2004b; Yancey, 2004), and diminishing purchases of US tobacco leaf by major cigarette manufacturers (Jones et al., 2008; Lindblom, 1999). The decline in domestic tobacco production and shift to larger tobacco agribusinesses also resulted in tobacco farmers making up a smaller number of the constituents of agricultural interest groups and political representatives (Wilson, 2005).

Recognizing the beginning of the rift between growers and manufacturers, public health groups made coordinated overtures to tobacco growers and agricultural interests, attempting to forge alliances over MSA negotiations, proposed FDA regulation of tobacco and encouraging crop diversification out of tobacco (Austin & Altman, 2000; Jones et al., 2008; Zaccaro & Altman, 2000). These efforts were promoted by President Bill Clinton’s administration (Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, 1998; Kuegel, Myers, Shepherd, Hill, Sroufe, Wheeler et al., 2001; Otanez & Glantz, 2009); the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s “Southern Tobacco Communities Project” (Austin & Altman, 2000; Institute for Environmental Negotiation & University of Virginia, 1997; Jones et al., 2008; Root, 2004); and the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, American Cancer Society and American Heart Association’s False Friends: The US Cigarette Companies’Betrayal of American Tobacco Growers report (Lindblom, 1999). These efforts damaged manufacturers’ credibility as an ally of agricultural interests (Austin & Altman, 2000; Jones et al., 2008).

Trickle-Down Effects of National Developments

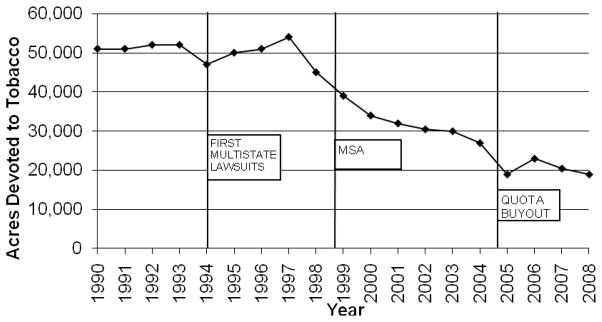

Between 1997 and 2008, acreage devoted to tobacco growing in South Carolina declined by more than half, from 54,000 acres to 19,000 acres (Figure 1) (United States Department of Agriculture, 2009a), leaving fewer than 200 South Carolina tobacco farmers (Hinshaw, 2008). In 2007, cash receipts from tobacco farming were $69 million out of $785 million from crops statewide, well behind greenhouse plants ($239 million), corn ($104 million) and soybeans ($82 million) (South Carolina Department of Agriculture, 2008c). South Carolina’s 65% decline in tobacco acreage from 1997 to 2008 mirrored the 45% to 65% declines in the four other main tobacco-producing states during the same period (United States Department of Agriculture, 2009b).

Figure 1.

Acreage Devoted to Tobacco Growing in South Carolina (1990–2008) (United States Department of Agriculture, 2009a)

The primary contributor to the decline in leaf production in South Carolina, and all other US tobacco-growing states, was reduced demand from US tobacco manufacturers who steadily increased purchases of foreign tobacco leaf (Beach et al., 2008; Lindblom, 1999). The end of the federal quota system also contributed to a decline in the proportion of South Carolina farmers making their living from tobacco production, reducing the relative weight of the tobacco crop among all crops as a priority of agricultural groups. This shift directly impacted the Department of Agriculture and the Farm Bureau’s political position on tobacco control; according to Larry Boyleston, Assistant Commissioner of Agriculture in 2009, who had worked with the Department since 1993:

[Commissioner] Tindal took something of an active role [in tobacco control debates]…. We supported, like all the other agricultural organizations at the time including Farm Bureau, … tobacco because it was a big income-producer …. Over time, as things changed, the programs changed, kept cutting back on quotas…. That’s why you see less action … from our department and others, because there is no tobacco program now … and as a result our policy has changed (Boyleston, 2009).

Russell Ott, lobbyist and legislative specialist with the Farm Bureau, explained that for the Farm Bureau, “it’s never really been about tobacco, it’s been about supporting farmers” as a whole (Ott, 2009).

The tobacco quota buyout also shifted production of tobacco from a market within the confines of the price support system towards direct contracting between the remaining tobacco growers and manufacturers. Direct contracts are appealing to both growers and manufacturers because they offer both supply and demand assurances beyond those available in the price support and quota systems (Crocker, 2009). However, contracts also cut growers’ political representatives out of the tobacco purchasing process, drastically reducing the role of the Department of Agriculture and the Farm Bureau in tobacco market politics (Crocker, 2009). This change cut off the main lines of communication between manufacturers and the Commissioner of Agriculture and reduced overlap in their positions on tobacco growing and, therefore, tobacco control (Boyleston, 2009; Crocker, 2009).

Both the decline in tobacco production and the upsurge of direct contracting led Commissioners of Agriculture and the Farm Bureau to focus their tobacco positions on diversification out of tobacco and ensuring the viability of all agriculture in the state, in contrast with their former strong opposition to tobacco control to protect tobacco as a viable crop (Crocker, 2009). Unlike his predecessor, Tindal, Commissioner of Agriculture Charles Sharpe (2002–2005) began publicly promoting crop diversification out of tobacco in 2003. Sharpe toured the state, explaining his diversification push to news outlets: “Look at tobacco. Tobacco has been our main crop for so many years, and now it’s gone. We have to find something to replace it” (Collins, 2003). The Farm Bureau and Department of Agriculture started working to secure funding for agricultural marketing programs from cigarette tax increase proposals based on arguments for diversification out of tobacco and general farm interests; according to Farm Bureau lobbyist Ott:

Our position … was that should the increase go into effect … we had to see some of that revenue come back to the farm … and the decision … was to try and benefit the largest sector of farmers possible …. If those tobacco farmers aren’t going to be able to transition into another crop, then what are they going to do? And for them to be able to transition into another crop, then it has to be financially viable. (Ott, 2009).

South Carolina public health groups took part in nationally-led efforts to reinforce the distancing of tobacco growers from manufacturers between 1997 and 2004, including the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s “Southern Tobacco Communities Project”(Austin & Altman, 2000; Institute for Environmental Negotiation & University of Virginia, 1997; Jones et al., 2008; Root, 2004; The Strom Thurmond Institute, 1999) and efforts to engage growers in promotion of a federal tobacco quota buyout bill that would include FDA regulation of tobacco (Brown et al., 2007; Staff and Wire Reports, 2004). While these overtures ended with the quota buyout in 2004, they opened lines of communication between public health and agricultural organizations and engendered good will in tobacco communities that had a residual positive impact on tobacco control policy advocacy (Barkley, 2009). Ott suggested that continued communication and support from health groups was instrumental in the Farm Bureau’s cooperation on cigarette taxes (Ott, 2009).

Tobacco Control Successes

In South Carolina, the tobacco control advocacy infrastructure slowly gained in coordination, funding and political prowess between 2000 and 2009 after a long period of ineffectiveness and disorganization (Sullivan et al., 2009). Starting in 2001, public health groups focused on raising the state’s lowest-in-the-nation cigarette tax, which had been defeated by manufacturers and agricultural interests through the 1990s (Sullivan et al., 2009). During the 2007/2008 legislative session, public health groups pushed a 50-cent per pack cigarette tax increase that passed the legislature for the first time since 1977, but was vetoed by Governor Mark Sanford (R) due to his general opposition to all tax increases rather than because it was a tobacco tax increase (Sullivan et al, 2009) (In May 2010, the South Carolina legislature passed a 50-cent per pack cigarette tax increase into law, this time overriding a veto by Governor Sanford. This was the state's first tobacco tax increase in 33 years (South Carolina Tobacco Collaborative, 2010).). The Farm Bureau and Commissioner of Agriculture helped craft and lobbied for the tax increase from 2006 to 2009, hoping to secure funding for the Department of Agriculture’s agriculture promotion and marketing program (Boyleston, 2009; Ott, 2009; Root, 2006; Sullivan et al., 2009). During the 2008 legislative session the Farm Bureau remained neutral during a period in which the tax increase proposal did not include agricultural funding because they were confident that the funding would be added back into the bill (Ott, 2009).

Tobacco control advocates had prominent successes in passing strong local clean indoor air policies and defeating weak state-level clean indoor air bills that were supported by manufacturers and were similar to those previously supported by manufacturers’ agricultural allies (Sullivan et al., 2009). Advocates passed 23 local clean indoor air ordinances between May 2006 and April 2009, including 12 under the threat of lawsuits based on alleged preemption of clean indoor air legislation (Sullivan et al., 2009). Unlike the 1980s, agricultural organizations did not oppose the local ordinances. At the state level, where public health lobbyists had been dominated by manufacturers and their allies, tobacco control advocates used their increased funding, coordination and political will to overpower the manufacturer lobby in 2008 when it advocated for (without support from the Farm Bureau (Ott, 2009) or Department of Agriculture) weak, preemptive clean indoor air bills that would have hamstrung their strong local ordinance efforts (Sullivan et al., 2009).

The neutral-to-favorable tobacco control stance of the Farm Bureau and Commissioners of Agriculture between 2003 and 2009 contributed to tobacco control successes by weakening the ability of manufacturers to strongly influence the pace and content of tobacco control policy at the state and local levels and by allowing the entrance of a public health voice into the traditionally agriculture-focused policy debates (Sullivan et al., 2009). Tobacco control advocacy also played a role in solidifying agriculture’s neutrality. Tobacco control advocates recognized that the Farm Bureau was separating from the manufacturers and took advantage of this situation by reaching out to the Bureau to work with them on cigarette tax proposals. Both the Farm Bureau and the Commissioner’s office indicated that they stopped opposing clean indoor air policies and shifted their focus on cigarette tax increases from opposition to making resources available for agricultural promotion in part because of a sense that public health groups were going to succeed on both policy initiatives. Ott explained that the Farm Bureau shifted position on the tax because they had “seen the writing on the wall…. We all agree it’s going to take place” (Ott, 2009). Similarly, Boyleston said that the Department of Agriculture “saw the writing on the wall” and shifted its focus to diversification out of tobacco and that it no longer opposed clean indoor air regulation because its members in the agricultural community “just all realize where we are now” (Boyleston, 2009). National-level tobacco market changes were the largest factors in the agricultural organizations’ shift on tobacco control, with public health advocates successfully leveraging the distancing to their advantage.

The agricultural groups’ positions on tobacco control pragmatically reflect their interests in protecting all farmers, indicating that their former alliances with manufacturers were based primarily on overlapping interests that no longer exist. According to Coretta Bedsole, lobbyist for the Farm Bureau (1998–2002) and the American Cancer Society (2001–2003) and 2008–2009 lobbyist for the South Carolina African-American Tobacco Control Network, the Farm Bureau worked with manufacturers when their interests intersected, but was not in “lock step” with manufacturers (Bedsole, 2008). Farm Bureau’s Ott said that as of 2009, “there is no coordination with the manufacturers,” but that if their interests were aligned they may eventually have to “shift back to some of those old alliances” (Ott, 2009).

Tobacco-Area Legislators

Not all of the manufacturers’ third-party allies shifted their position based on changes in tobacco growing and tobacco control politics. As of 2008, some South Carolina legislators, particularly Representatives, from tobacco-growing areas remained strong supporters of manufacturer strategies to oppose tobacco control policies. Several representatives from Horry County, which had the highest concentration of tobacco growing in 2007 among the few remaining tobacco-growing counties, remained frequent sponsors of the manufacturer-supported weak “clean indoor air” bills introduced to halt strong local clean indoor air activity (Sullivan et al., 2009). Legislators from historical tobacco-growing counties in the Pee Dee, however, were no longer the strong allies of tobacco manufacturers.

DISCUSSION

In South Carolina an iron triangle existed around tobacco policy in the late 1970s: independent interest groups (South Carolina Farm Bureau), government agency (Commissioner of Agriculture) and legislators (from tobacco-growing areas). Tobacco manufacturers targeted entities in each arm of the triangle, effectively building strong behind-the-scenes alliances by arguing that their interests overlapped with those of each arm. Through these alliances, combined with overt direct manufacturer lobbying, manufacturers significantly influenced state tobacco policy making for two decades, undermining tobacco control efforts through 2002. The public health community was too weak at the time to effectively counter the tobacco manufacturers’ and their allies’ arguments or to break into the triangle. However, once there was a decline in overlapping interests between manufacturers and state interest groups and bureaucrats, the agriculture organizations shifted their stance on tobacco control to a neutral position, reflecting their members’ interests. By stepping back as the key experts on tobacco policy in the area of tobacco control, these organizations opened up the field into an issue network, allowing public health groups to display their expertise and become successful participants in the state tobacco control policy debate.

While scholars have studied manufacturers’ alliance with individual tobacco farmers from a grassroots perspective (D. Altman et al., 1997; D. G.Altman et al., 1996; Austin & Altman, 2000; Beach et al., 2008; Brown et al., 2007; Crankshaw et al., 2009; Fisher, 2000; Jones et al., 2008; O’Connell, 2002; Zaccaro & Altman, 2000; Zhang & Husten, 1998), an alliance that has also faltered since the late 1990s, state-level agricultural organizations represent a largely unexplored third-party historically courted by manufacturers to influence tobacco control policy in tobacco-growing states. Similarly, while state agencies have acted in concert with manufacturers as part of iron triangle politics in the past (Michael Givel & Glantz, 2004a), there is limited literature on manufacturers’ cultivation of state agencies as third-party allies and none available on state Departments of Agriculture in this context.

The iron triangle framework applied well to tobacco policy making in a tobacco-growing state such as South Carolina: tobacco policy making was a specialized area in which tobacco growers’ representatives in the legislature, interest group community and bureaucracy were considered the experts for decades. The shift to an issue network on the topic, allowing for the serious inclusion of public health groups in the debate, was due to the increasing ambivalence of agricultural organizations towards tobacco control policy. The issue network around tobacco control policy expanded to include both agricultural and public health perspectives among interest groups, legislators and bureaucrats. As such, it remained an insider political structure, but it one that was no longer dominated by one perspective, as had been the case through the old agricultural iron triangle in South Carolina.

Third-party allies provide manufacturers with a publicly credible voice, a tactic that manufacturers have successfully utilized to oppose clean indoor air and excise tax policies throughout the US (Campbell & Balbach, 2008; Dearlove et al., 2002;M. S. Givel & Glantz, 2001; Mandel & Glantz, 2004; Ritch & Begay, 2001). While tobacco manufacturers experience more credibility in tobacco growing and producing states than in other US states, agricultural allies amplified their already strong opposition to tobacco control policies. Independent third-party allies are considered to legitimately represent the policy interests of their constituents and members (Campbell & Balbach, 2008). This was particularly true of agricultural groups: In 1990, Philip Morris’ internal analysis of the “Tobacco Constituency Group,” an intra-company group of Philip Morris segments dealing with tobacco growers developed in the early 1990s, explained that “local growers have more credibility in legislatures than do hired guns” ([Author unknown], 1990).

Tobacco manufacturer allies can either be manufacturer created or sponsored entities (front groups) or pre-existing, independent interest groups whose interests are perceived to overlap with the tobacco manufacturers (third-party allies). While third-party allies often do receive financial support from manufacturers, their credibility as a political supporter of manufacturer positions on tobacco control policy is much stronger than front groups (Campbell & Balbach, 2008). However, as highlighted by this case study, third-party allies’ formal independence from manufacturers represents a weakness in the continuity of their alliance. Manufacturers have long recognized that in their alliances with interest groups (M. S. Givel & Glantz, 2001) independence of their ally was both the “greatest strength” and a “limit on effectiveness of those coalitions on our issues,” according to a 1990 Tobacco Institute budget and planning document that continued, “Allies may not agree or even have an interest in all industry issues, and may not be willing or able to assist in all ways requested” (Tobacco Institute, 1990). They also noted that “tobacco family and farm issues” were particularly vulnerable areas (Tobacco Institute, 1990).

Policy Implications

The dissolution of the iron triangle of manufacturers third-party allies provides an example that other tobacco-growing states could follow to better integrate themselves into the insider political structures around tobacco control policy making. The South Carolina case study exemplifies how pragmatic concerns raised over decreasing overlap between manufacturer and agricultural interests can be leveraged by public health groups to neutralize strong tobacco control opposition.

The national developments weakening the manufacturers’ alliance with agricultural groups provided the necessary environmental changes that allowed an opening in the formerly insulated policy iron triangle. Public health groups in the state took advantage of this shift to become a stronger voice in the state policy process by engaging and educating former agricultural allies and legislators about the public health imperatives. Through increased funding from national-level tobacco control organizations, strategic planning and organizational capacity, the public health groups were able to achieve incrementally greater successes each year, increasing the perception that they were bound to eventually succeed. The opening provided by the shift in agricultural positions allowed the public health groups access to the debate, permitting a shift from the iron triangle to an issue network policy structure on tobacco control to take place.

As tobacco control policies progress in the US states and internationally, the strength of manufacturers’ third-party allies becomes more tenuous. However, they continue to play an instrumental role in the defeat of tobacco control proposals in the US and worldwide (Mamudu, Hammond, & Glantz, 2008). Public health advocates can use this example of incongruence of interests to identify rifts between manufacturers and their third-party allies and to break down remaining agricultural alliances and other tobacco manufacturer alliances.

Remaining Challenges

Literature on tobacco control policymaking in multiple tobacco-growing states has consistently pointed to the tradition, or “cultural icon” (Chaloupka et al., 2002), of tobacco growing as a key challenge in attempts to pass tobacco control measures (D. G. Altman et al., 1996; Greathouse, Hahn, Okoli, Warnick, & Riker, 2005; Hahn, Rayens, Rasnake, York, Okoli, & Riker, 2005). While the real economic significance of tobacco has declined, as reflected in the Farm Bureau and Commissioner’s tobacco control policy shifts, the residual cultural significance of tobacco has not waned proportionately. Tobacco control advocates in South Carolina and other tobacco-growing states continue to point to tobacco-growing status as a cultural obstacle to tobacco control and often succumb to the belief in its cultural importance themselves, even if growing is a negligible economic contributor. The Director of Tobacco States for the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids explained that, “There’s so much nostalgia, and the heritage – even really liberal, progressive advocates will still say in all of these states, ‘Well, what about the tobacco farmers?,’” but that this attitude is “more perception than it is reality” and is based on the “overall cultural environment more than [manufacturers’] direct influence” (Barkley, 2008). The Cigarette Tax Campaign Coordinator for the South Carolina Tobacco Collaborative (the state’s primary tobacco control advocacy coalition), explained that working with agricultural interests to fund their programs from a tax increase was instrumental because of “the ongoing sentiment in our state that we need to take care of our tobacco farmers…. It is still part of the fabric of our state because of the history of tobacco in our state” (Davis, 2008).

The notion that tobacco is culturally important increases the perception of tobacco’s economic importance out of proportion with reality, creating an obstacle for tobacco control advocates in challenging manufacturers’ remaining agricultural arguments and allies. This misperception may be particularly relevant in countering remaining pro-tobacco manufacturer sentiment among tobacco-area legislators.

Conclusion

Tobacco control remained a prominent issue in tobacco-growing states in 2009, as tobacco control advocates attempted to close the gap in tobacco control policy between their states and the rest of the nation. During the first half of 2009, Virginia passed a weak clean indoor air law, allowing smoking in ventilated rooms, and North Carolina passed a strong, but limited, clean indoor air law that made restaurants and bars (but not workplaces) smokefree, without significant opposition from agricultural groups, and many tobacco-growing states were considering tax increase proposals (Barkley, 2009). South Carolina provides a useful case study for the agricultural element of tobacco control policymaking, but some tobacco-growing states, particularly those with in-state manufacturing interests like Virginia and North Carolina or those with remaining tobacco-growing across all regions of the state, may face additional difficulties in defeating the lingering cultural assumptions about tobacco. By relying on the pragmatism of agricultural organizations and their responses to changes in the tobacco market and farming generally to show that their interests are no longer with protecting tobacco manufacturers, public health groups have the opportunity to renew efforts to partner with these potentially powerful groups to neutralize their opposition or engage their active support for tobacco control policies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA-61021). The funding agency played no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sarah Sullivan, UC San Francisco.

Stanton Glantz, University of California.

References

- Altman D, Levine D, Howard G. Tobacco Farming and Public Health: Attitudes of the General Public and Farmers. Journal of Social Issues. 1997;53(1):113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG, Levine DW, Howard G, Hamilton H. Tobacco farmers and diversification: opportunities and barriers. Tob Control. 1996;5(3):192–198. doi: 10.1136/tc.5.3.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin WD, Altman D. Rural economic development vs. tobacco control? Tensions underlying the use of tobacco settlement funds. J Public Health Policy. 2000;21(2):129–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach RH, Jones AS, Tooze JA. Tobacco Farmer Interest and Success in Income Diversification. J Agr Appl Econ. 2008;40(1):53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Brown AB, Rucker RR, Thurman WN. The End of the Federal Tobacco Program: Economic Impacts of the Deregulation of U.S. Tobacco Production. Rev Agr Econ. 2007;29(4):635–655. [Google Scholar]

- Browne W. Policy making in American States. Am Politics Res. 1987;15(1):47–86. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Balbach ED. Mobilising public opinion for the tobacco industry: the Consumer Tax Alliance and excise taxes. Tob Control. 2008;17(5):351–356. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.025338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, & Promotion. Prevalence and Trends Data: Tobacco Use - 2008. 2008 September 19; 2008. Available at: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/list.asp?cat=TU&yr=2008&qkey=4396&state=All.

- Chaloupka F, Hahn E, Emery S. Policy Levers for the Control of Tobacco Consumption. Kentucky Law Journal. 2002;90(4):1009–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Collins J. SC farmers go nuts for new federal rules. The State; Columbia, SC: 2003. p. B3. [Google Scholar]

- Crankshaw E, Beach R, Austin W, Altman D, Snow Jones A. North Carolina tobacco farmers' changing perceptions of tobacco control and tobacco manufacturers. J Rural Health. 2009;25(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearlove JV, Bialous SA, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry manipulation of the hospitality industry to maintain smoking in public places. Tob Control. 2002;11(2):94–104. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.2.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher L. Tobacco farming and tobacco control in the United States. Cancer Causes & Control. 2000;11(10):977–979. doi: 10.1023/a:1026756331165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givel M, Glantz S. Failure to defend a successful state tobacco control program: policy lessons from Florida. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(5):762–767. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.5.762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givel M, Glantz S. Political Insiders Without Grassroots Advocacy in the Administration of a Missouri Tobacco-Control Youth-Access Program. Public Integrity. 2004a;7(1):5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Givel M, Glantz SA. The “global settlement” with the tobacco industry: 6 years later. Am J Public Health. 2004b;94(2):218–224. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givel MS, Glantz SA. Tobacco lobby political influence on US state legislatures in the 1990s. Tob Control. 2001;10(2):124–134. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.2.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden MM. Interest groups in the rule-making process: Who participates? Whose voices get heard? J Pub Admin Res Theory. 1998;8(2):245–270. [Google Scholar]

- Greathouse LW, Hahn EJ, Okoli CT, Warnick TA, Riker CA. Passing a smoke-free law in a pro-tobacco culture: a multiple streams approach. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2005;6(3):211–220. doi: 10.1177/1527154405278775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn E, Rayens MK, Rasnake R, York N, Okoli CTC, Riker CA. School Tobacco Policies in a Tobacco-Growing State. J Sch Health. 2005;75(6):219–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AS, Austin WD, Beach RH, Altman DG. Tobacco farmers and tobacco manufacturers: implications for tobacco control in tobacco-growing developing countries. J Public Health Policy. 2008;29(4):406–423. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2008.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan AG. Iron Triangles, Woolly Corporatism and Elastic Nets: Images of the Policy Process. Journal of Public Policy. 1981;1(1):95–123. [Google Scholar]

- Lightwood JM, Dinno A, Glantz SA. Effect of the California tobacco control program on personal health care expenditures. PLoS Med. 2008;5(8):e178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamudu H, Hammond R, Glantz S. Tobacco industry attempts to counter the World Bank report Curbing the Epidemic and obstruct the WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(11):1690–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel LL, Glantz SA. Hedging their bets: tobacco and gambling industries work against smoke-free policies. Tob Control. 2004;13(3):268–276. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.007484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miroff B, Seidelman R, Swanstron T. The Democratic Debate: An Introduction to American Politics. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell P. Tobacco control in the land of the golden leaf. Has political perception kept pace with reality? N C Med J. 2002;63(3):175–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otanez MG, Glantz SA. Trafficking in Tobacco Farm Culture: Tobacco Companies’ Use of Video Imagery to Undermine Health Policy. Visual Anthropology Review. 2009;25(1):1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-7458.2009.01006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritch WA, Begay ME. Strange bedfellows: the history of collaboration between the Massachusetts Restaurant Association and the tobacco industry. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(4):598–603. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.4.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skok J. Policy issue networks and the public policy cycle: a structural-functional framework for public administration. Public Admin Rev. 1995;55(4):325–332. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan S, Barnes R, Glantz S. Tobacco Control Policy Making. United States: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education; 2009. Shifting Attitudes Towards Tobacco Control in Tobacco Country: Tobacco Industry Political Influence and Tobacco Policy Making in South Carolina. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/278790h5. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Reducing Tobacco Use: A Report of the Surgeon General. Altanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GK. Farmers, Interests and the American State. In: Halpin D, editor. Surviving Global Change? Agricultural Interest Groups in Comparative Perspective. Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yishai Y. From an iron triangle to an iron duet? Health policy making in Israel. European J Political Res. 1992;21:91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Zaccaro DJ, Altman DG. Tobacco growers’ knowledge of revenue distribution and foreign prices: implications for health education. Health Educ Res. 2000;15(2):175–180. doi: 10.1093/her/15.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Husten C. Impact of the Tobacco Price Support Program on tobacco control in the United States. Tob Control. 1998;7(2):176–182. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Original Source Materials

- TAN. Plan of Action: Expansino of TAN into the Southeastern States - 1981. 1980 June 11; [Author Unknown] 1980. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rsc28b00.

- South Carolina: A State Analysis. RJ Reynolds; 1985. [Author unknown] Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ppx77c00. [Google Scholar]

- State of the States. Lorillard; 1987. [Author unknown] Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vae00e00. [Google Scholar]

- Philip Morris; 1990. Agricultural, Plant Community, Government, and Public Affairs - an Integrated Approach. [Author unknown] Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qyb95c00. [Google Scholar]

- Bankhead J. After Action Analysis on Subcommittee Hearing on the South Carolina Clean Indoor Air Act, H – 3178. 1980 Feb 27; Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rff31e00.

- Bankhead J. Prognosis for Legislation in 1982 in Southeast Area. Tobacco Institute; 1981. Oct 19, Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cpz22f00. [Google Scholar]

- Bankhead J. Report Number One on South Carolina Tobacco Tax Increase Legislation. Brown & Williamson; 1982a. Dec 16, Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/paf43f00. [Google Scholar]

- Bankhead J. South Carolina Legislative Situation Report. Brown & Williamson; 1982b. Dec 21, Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/maf43f00. [Google Scholar]

- Bankhead J. Tobacco Institute; 1983a. RE: Report Number Three on South Carolina Cigarette Tax Increase Legislation. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mlq09a00. [Google Scholar]

- Bankhead J. Re: South Carolina tax increase. Tobacco Institute; 1983b. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/llq09a00. [Google Scholar]

- Bankhead J. Brown & Williamson; 1983c. Jan 14, Report Number Two on South Carolina Cigarette Tax Increase Legislation. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kaf43f00. [Google Scholar]

- Bankhead J. Richland County, South Carolina. RJ Reynolds; 1985. Oct 10, Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pnp35d00. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley A. Interview of Amy Barkley, Director of Tobacco States and Mid-Atlantic for Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, by Sarah Sullivan. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley A. Interview of Amy Barkley, Director of Tobacco States and Mid-Atlantic for Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, by Sarah Sullivan. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bedsole C. Interview of Coretta Bedsole, Lobbyist for the South Carolina African American Tobacco Control Network, by Sarah Sullivan. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bell H. Letter regarding H 2050. Tobacco Institute. 1983 Jan 10; Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/klq09a00.

- Boyleston L. Interview of Larry Boyleston, South Carolina Assistant Commissioner of Agriculture, by Sarah Sullivan. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Tobacco Producers, Health Groups Unite to Fight Youth Smoking and Stabilize Tobacco Communities. 1998 March 16; 1998. Available at: http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/Script/DisplayPressRelease.php3?Display=75&zoom_highlight=stabilization.

- Crocker B. Interview of Beth Crocker, General Counsel and Director of Legal Affairs for the South Carolina Department of Agriculture, by Sarah Sullivan. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Davis K. Interview of Kelly Davis, Cigarette Tax Campaign Coordinator for the South Carolina Tobacco Collaborative, by Sarah Sullivan. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- DeLoach, et al., v. Philip Morris Companies, et al., No. 00-CV-1235. (2000). U.S. District Court, M.D.N.C.

- Dowdell JS. Tobacco Grower Relations. RJ Reynolds; 1977. Mar 09, Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vpj99d00. [Google Scholar]

- Heclo H. Issue Networks and the Executive Establishment. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw D. Once SC’s livelihood, tobacco no longer rules the state. The Beaufort Gazette; Beaufort, SC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes B. Tobacco: why we grow it. The State; Columbia, SC: 1989. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Environmental Negotiation, & University of Virginia. Southern Tobacco Communities Project. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Grove EN. History and Evaluation of the Tobacco Program 1933–74. Tobacco Institute; 1975. Jan 27, Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/npo92f00. [Google Scholar]

- Kuegel WM, Myers M, Shepherd A, Hill J, Sroufe R, Wheeler MC, et al. Tobacco at a Crossroad: A Call for Action -- Final Report of the President’s Commission on Improving Economic Opportunity in Communities Dependent on Tobacco Production While Protecting Public Health. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom EN. False Friends: The US Cigarette Companies’ Betrayal of American Tobacco Growers. American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Markoe L. Tobacco’s future tied to buyout. The State; Columbia, SC: 2004. p. A1. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Money in State Politics. 2008 Available at: http://www.followthemoney.org/

- Ott R. Interview of Russell Ott, Legislative Specialist with the South Carolina Farm Bureau, by Sarah Sullivan. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- PR Newswire. Tobacco Institute; 1995. Dec 02, South Carolina Farm Bureau Passes Resolution Stating, the FDA Has No Place on the Farm. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ihx40c00. [Google Scholar]

- Root T. Senate OKs tobacco buyout. The Sun News; Myrtle Beach, SC: 2004. p. A1. [Google Scholar]

- Root T. Cigarette tax, farm-goods branding discussed. The Sun News; Myrtle Beach, SC: 2006. p. C5. [Google Scholar]

- Scoppe CR. Special report: tobacco’s uncertain autumn: tobacco has strong allies in legislature, governor. The State; Columbia, SC: 1994. p. A1. [Google Scholar]

- South Carolina Department of Agriculture. Commissioners of Agriculture 1987 - Present. 2008a Available at: https://agriculture.sc.gov/content.aspx?ContentID=658.

- South Carolina Department of Agriculture. South Carolina Department of Agriculture: About Us. 2008b Available at: http://agriculture.sc.gov/content.aspx?ContentID=509.

- South Carolina Department of Agriculture. Top Ten Commodities: 2007 Cash Receipts. 2008c Available at: http://agriculture.sc.gov/content.aspx?MenuID=112.

- South Carolina Farm Bureau. State Legislative News. Tobacco Institute; 1983. Jan 07, Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jlq09a00. [Google Scholar]

- South Carolina Farm Bureau. South Carolina Farm Bureau: History. 2009 Available at: http://www.scfb.org/aboutus/history.aspx.

- South Carolina General Assembly. Journal of the House of Representatives, Tuesday, January 9, 1996. 1996 Available at: http://www.scstatehouse.gov/sess111_1995-1996/hj96/19960109.htm.

- South Carolina Tobacco Collaborative. Cigarette tax. 2010 Available at: http://www.sctobacco.org/cigarettetax.aspx.

- Staff and Wire Reports. Tobacco buyout passes as part of corporate tax bill. The State; Columbia, SC: 2004. p. B6. [Google Scholar]

- The Strom Thurmond Institute. Agenda: South Carolina Tobacco Forum; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tindal DL. No Title. Lorillard; 1982. Dec 08, Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gpf31e00. [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco Institute. Tobacco Inst Corporate Campaign Contributions Summary 1985. Tobacco Institute; 1986. Jan 25, Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wiz22f00. [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco Institute. Tobacco Institute; 1990. The Tobacco Institute Public Affairs Division Proposed Budget and Operating Plan 1990. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uoj52f00. [Google Scholar]

- United Press International. Cigarette Tax Plan Opposed. Brown & Williamson; 1972. Jan 14, Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ovp01c00. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture. National Agricultural Statistics Service: South Carolina Data: Crops. 2009a Available at: http://www.nass.usda.gov.

- United States Department of Agriculture. National Agricultural Statistics Service: Tobacco (All Classes): National Statistics. 2009b Available at: http://www.nass.usda.gov/QuickStats/index2.jsp.

- Wheeler F, Sneegas K. South Carolina Project ASSIST: Site Analysis. Tobaccodocuments.org; 1992. Oct 1, http://tobaccodocuments.org/nysa_ti_s3/TI38961601.html. [Google Scholar]

- Yancey CH. RJR settles class-action lawsuit. Southeast Farm Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]