Abstract

Background

Currently, the only tests capable of determining the serotype of a dengue virus (DENV) infection require sampling during the acute viremic period. No test can accurately detect the serotype of past DENV infections. The standard assay for detecting serotype-specific antibody against DENV is PRNT though the performance of this test continues to be evaluated.

Methods

From a cohort study among schoolchildren in Thailand PRNT were determined in serum samples collected before and after infection. A multinomial logistic regression model was used to infer the serotype of intercurrent DENV infections. Models were validated based on PCR identification of DENV serotypes.

Results

The serotype of infection inferred by the model corresponded with PCR in 67.6% of cases and the kappa statistic was 0.479. A model for 35 cases with primary seroconversion correctly identified serotypes of infection in 77.1% of cases compared to 66.9% using a model for 169 cases with secondary seroconversion. The best model using only post-infection PRNT values correctly inferred the serotype of infection in 60.3% of cases.

Conclusions

A statistical model based on both pre- and post-infection PRNT values can be used for inference on the serotype of DENV infections in prospective studies such as vaccine trials.

Keywords: dengue, children, serotype, Plaque reduction neutralization, vaccine, antibodies, Thailand

INTRODUCTION

Dengue virus (DENV) is one of the most important emerging viruses worldwide. DENV has four serotypes (DENV-1, 2, 3 and 4) that cause an estimated 34 million reported illnesses and over 20,000 deaths per year [1–4]. With no curative treatment and the difficulty of sustaining vector control programs, most hope for dengue control is based on the development of a safe and effective vaccine [5]. Several dengue vaccine candidates are in an advanced stage of development and phase 3 trials are about to start in endemic countries [2, 6].

Currently, the measurement of plaque reduction neutralization titers (PRNT) is the most widely used test for determining serotype-specific antibodies against DENV [7]. This test was originally developed in the late 1960’s by Russell and Nisalak [8] and later adapted to quantify serotype-specific antibody titers using probit analysis [9].

In response to a DENV infection, cross-reactive antibodies are produced against epitopes of DENV proteins that are identical across serotypes, allowing these antibodies to react to and perhaps neutralize more than one serotype [10, 11]. Despite this cross-reactivity of DENV antibodies, PRNT50 has been used to make inference on the serotype of DENV infections [12–16]. So far, no universal definitions have been developed for the interpretation of PRNT50 data for this purpose. Previous experimental studies demonstrated that in case of primary DENV infections, the highest late convalescent PRNT values are against the infecting serotype [17, 18]. The use of PRNT to infer the serotype of infection for secondary infections or heterotypic antibody responses is generally discouraged [15, 18, 19]. Although these principles have been applied in multiple sero-epidemiological studies [13, 14, 20, 21], their validity in such studies was never formally quantified by comparison to a gold standard (virus detection) and statistical testing.

In a prospective study in Kamphaeng Phet, a monotypic antibody response was defined as PRNT50 <10 for three serotypes and ≥ 10 for only one serotype or PRNT50 ≥ 10 for more than one serotype, but ≥ 80 for only one serotype. In these cases, the DENV serotype with the highest PRNT50 was assumed to be the infecting serotype [20]. The infecting serotype was not determined for cases with a heterotypic immune response [20]. In a previous, similar cohort study in Bangkok, acute and convalescent phase PRNT50 values from school children were found to be sufficiently clear (monotypic) to determine the infecting serotype in 27 of 47 (57%) acute primary infection as defined by HAI seroconversion [14].

Other prospective studies in Thailand, Venezuela, and Indonesia measured baseline and post-infection 70% PRNT in schoolchildren and determined the DENV serotype of primary infections [13, 15, 21]. These were defined as no detectable PRNT70 at baseline and a monotypic antibody response in the first year [13, 15, 21]. These studies also identified the serotype of secondary infections (PRNT70 against a different DENV serotype compared to monotypic baseline values) [13, 15, 21]. For both primary and secondary infections, the serotype with the highest PRNT70 values was assumed to be the most recently infecting serotype [13, 15, 21]. Finally, in a serosurveillance study in Singapore, exposure to DENV serotypes was directly infered from PRNT50 antibody levels against different serotypes without regard to possible cross-reactivity [12].

Recent reviews have identified the need for a better standardization of PRNT [7, 22–24]. If PRNT assays are to be used to determine vaccine efficacy, to validate new serological tests for dengue or in disease surveillance, then the uncertainty of PRNT outcomes should be known to prevent inference based on potentially biased or inaccurate estimates.

We studied neutralizing dengue antibody responses using data collected as part of a prospective study of DENV transmission in Thailand [25, 26]. We developed a statistical model to determine the DENV serotype of acute infections based on pre- and post-infection PRNT50 values.

METHODS

Study cohort

Full details on study methodology have been published before [25, 26]. Briefly, school-age children from grades 1–5 were enrolled in January 1998 from 12 non-randomly selected schools in Muang subdistrict, Kamphaeng Phet province, Thailand. In the next years, new first grade children were enrolled each January and children were censored after graduating from grade 6.

Blood sampling

Each year from January to March, a blood sample for plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells was collected from study volunteers. Three additional blood samples for dengue serology were taken from all volunteers each year in June, August and November. Children that were absent from school or visited a school nurse were visited by a village health worker and referred to a public health clinic if fever or a history of fever in the past 7 days was found. Acute-illness blood samples were taken in case of febrile illness and a convalescent blood sample was taken 14 days after the illness.

Serological assays

RT-PCR for DENV RNA was done within 6 days of onset of symptoms in all children that presented with fever. For all children that had evidence of acute DENV infection (by serology or detection of virus), PRNT50 was measured in blood samples taken before the infection and at least one month after the infection.

All PRNT50 assays were done in the same laboratory according to a standard protocol. PRNT50 was determined by infection of a monolayer of LLC-MK2 cells with a constant amount of virus in the presence of 4-fold serial dilutions of heat-inactivated plasma from patients (1:10 to 1:2560) [20]. The reciprocal 50% neutralization titer was calculated with a log probit regression method. PRNT50 values <10 were considered undetectable.

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects or their parents/guardians and the protocol of the study for data collection was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Boards and regulatory agencies of the institutes involved as previously described [25, 26]. Secondary data analysis at the University of Pittsburgh and Johns Hopkins University was performed using de-identified data, hence was not deemed human subjects research.

Statistical analysis

Pre-infection PRNT values were defined as those obtained using plasma collected before the incident DENV infection. Post-infection PRNT values were defined as those obtained using plasma collected at least one month after the incident DENV infection. All children for which the DENV serotype could be determined by RT-PCR and for which pre- and post-infection PRNT values were available were used in our analysis. All PRNT values were log transformed (log base 10) after adding one (setting PRNT <10 to a value of 1) to obtain normal distributions.

We developed a multinomial logistic regression model to estimate for each infection the probability that it was caused by of DENV serotype 1, 2, 3 or 4. The outcome variable for each individual was the serotype of infection as detected by RT-PCR. The predictor variables considered were the log transformations of pre- and post-infection PRNT values for DENV-1, 2, 3, 4 and Japanese encephalitis virus (JE). The best fitting model was selected based on Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) and log-likelihood ratio tests comparing different models. The model determined the average association between the pre- and post-infection PRNT values and PCR outcomes and for each subject, the probability of each serotype to be the infecting serotype.

The DENV serotype with the highest probability given by the model was classified to be the infecting serotype. We performed out-of-sample validation by evaluating the performance of the model for data that was not used to fit the parameters of the regression model. For this, the prediction for each case was given by the model that was trained on all observations except that one case (leave-one-out validation).

Model predictions were compared to PCR outcomes and three indicators were calculated: 1) the proportion of predictions that correctly identified the infecting serotype (positive agreement), 2) the proportion of predictions that correctly rejected the non-infecting serotypes (negative agreement) and 3) a kappa statistic. These indicators are commonly used to estimate the validity of tests with more than two categories (multinomial) [27].

In addition to the model based on pre- and post-infection PRNT values of all observations (model A), model performance was also assessed for three different scenarios: 1) only using post-infection PRNT values of all observations (model B), 2) using pre- and post infection PRNT values for cases with pre-infection PRNT values <10 for all serotypes (“primary seroconversion”, model C) and 3) using pre- and post infection PRNT values for cases with pre-infection PRNT values ≥10 for at least one DENV serotype (“secondary seroconversion”, model D).

Finally, we stratified the evaluation of model predictions by the absolute difference in predicted probability of infection between the serotype with the highest and the serotype with the second highest probability given by the model. Intuitively, if the model predicted one serotype with high probability, than we anticipated that these results would be more accurate than if the model predicted multiple serotypes with similar probabilities. We evaluated the performance of the model as a function of differences in the highest and next highest probabilities predicted by our model.

Statistical analyses were performed with the R-system (version 2.9.2).

RESULTS

Description of the sample

Between January 1998 and November 2002, PCR assays were done for a total of 299 symptomatic DENV infections that occurred among 296 children in the cohort. Pre- and post-infection PRNT values were available for 286 infections. In most cases, pre-infection samples were drawn in January, February or March and post-infection samples in November. For one infection that occurred in January, pre- and post-infection PRNT values were measured in samples from the previous and following November. PCR results were negative in 82 cases, leaving a total of 204 cases for our analysis. On average, the time between pre-infection PRNT and PCR was 5.4 months (95%CI: 5.2–5.6, range 0.3 to 19 months) and between PCR and post-infection PRNT 4.1 months (95%CI: 3.9–4.2, range 1.1 to 9.4 months).

Children from all 12 schools were included with ages ranging from 7 to 15 years (mean: 10.2 years, sd: 1.5 years). Table 1 provides the distribution of dengue cases according to serotype and study year. Overall, DENV-2 was the most commonly infecting serotype (49.0%) followed by DENV-3 (31.9%). Only 5 cases of DENV-4 were identified (2.5%).

Table 1.

Distribution of dengue serotypes per year

| PCR outcome | 1998 (%) | 1999 (%) | 2000 (%) | 2001 (%) | 2002 (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DENV-1 | 8 (16.7) | 15 (33.3) | 0 | 7 (9.2) | 4 (14.8) | 34 (16.7) |

| DENV-2 | 3 (6.2) | 25 (55.6) | 8 (100) | 47 (61.8) | 17 (63.0) | 100 (49.0) |

| DENV-3 | 37 (77.1) | 5 (11.1) | 0 | 22 (29.0) | 1 (3.7) | 65 (31.9) |

| DENV-4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (18.5) | 5 (2.4) |

| Total | 48 | 45 | 8 | 76 | 27 | 204 |

Patterns in pre- and post-infection PRNT values

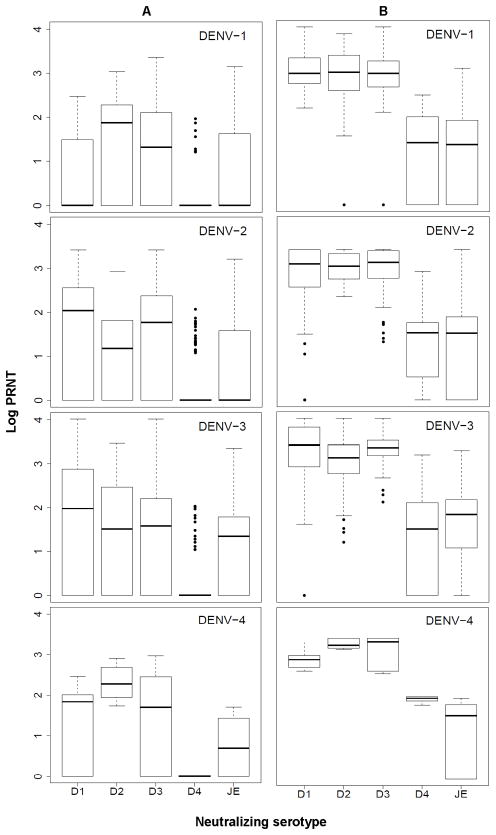

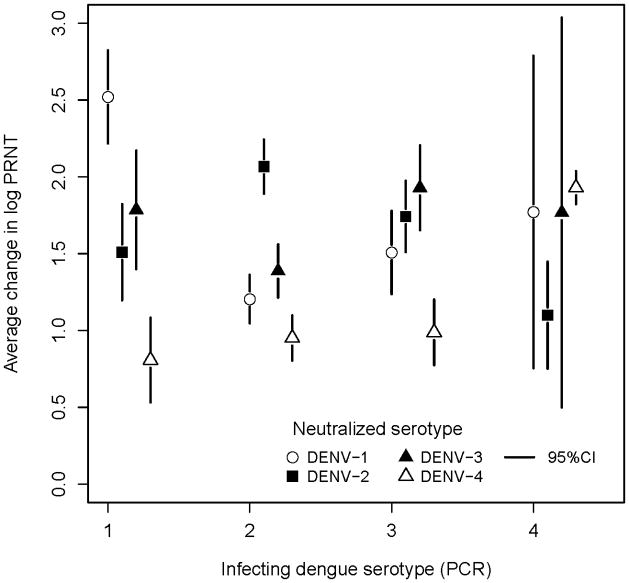

Figure 1 shows the distribution of pre- (Figure 1a) and post-infection (Figure 1b) neutralization titers to each of the DENV serotypes for individuals infected with DENV-1, 2, 3 and 4. This figure illustrates that on average, after infection with any DENV serotype, neutralization titers to all the other serotypes increased as well. However, in all cases the average increase of log PRNT values from pre- to post infection was highest for the serotype of the most recently detected infection (Figure 2). This figure also indicates that infection with DENV-1 or 2 was associated with an increase in DENV-3 antibodies, infection with DENV-3 was associated with increases in antibody levels against both DENV-2 and 1 and DENV-4 infection was associated with an increase in both DENV-1 and DENV-3 antibody titers.

Figure 1.

Log neutralization titers to all dengue serotypes and JE for individuals in which an infection with DENV-1, 2, 3 or 4 was detected by active surveillance; A) range, median and 25–75% inter-quantile ranges of log neutralization titers are shown for pre-infection samples; B) as in a, but for post-infection samples.

Figure 2.

Average change in log neutralization titers from pre- to post-infection to dengue serotypes for children infected with DENV-1, 2, 3 or 4 as detected by PCR during active surveillance.

Pre- and post-infection PRNT values are associated with the infecting DENV serotype

A multinomial logistic regression model was developed to predict the most recently infecting serotype using pre- and post-infection PRNT values for all children in our sample (Model A). The probability of a DENV serotype to be the infecting serotype was lower if pre-infection antibody titers against that serotype were high. The probability that DENV-1 was the infecting serotype decreased by ~90% for each log increase in pre-infection DENV-1 antibodies. The probability that DENV-2, 3 or 4 was the infecting serotype decreased by 90%, 63% and 100%, respectively, per log increase in pre-infection antibody titers against these serotypes. All these associations were highly statistically significant except for DENV-4, for which there were very few observations (making most inference on DENV-4 in this analysis not meaningful).

Secondly, the probability that each DENV serotype was the infecting serotype was higher if post-infection antibody titers against that serotype were higher. Depending on the outcome serotype of the model (DENV-2/DENV-1, DENV-3/DENV-1, DENV-4/DENV-1), the probability that DENV-1 was the infecting serotype increased 11 to 697 fold for each log increase in post-infection antibody titers against DENV-1. The probability that DENV-2, 3 or 4 was the infecting serotype increased 72, 269 and 1809 fold, respectively, per log increase in post-infection PRNT value against these serotypes. These associations were also highly statistically significant, except for DENV-4.

Inferring the infecting serotype based on patterns in PRNT values

Although an optimal model was developed based on all observations in our sample, we present here the results from serotype predictions using leave-one-out validation to best represent application of our model to external data. The inferred serotypes and the measured PCR values are compared in Table 2. Using pre and post-season PRNT values (Model A), out of 30 DENV-1 infections identified by the model, 20 (66.7%) corresponded to the PCR outcome. Of 108 and 60 infections identified to be DENV-2 and DENV-3 respectively, 81 (75.0%) and 36 (60.0%) were identified correctly. Results for DENV-4 infections were not very meaningful due to the low number included (5). Overall, the percent positive agreement between the model and PCR was 67.6%, the percent negative agreement was 89.2% and the kappa statistic was 0.479.

Table 2.

Serotypes inferred by the model vs. PCR results (using Model A)

| PCR | Inferred by multinomial model | Total (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DENV-1 (%) | DENV-2 (%) | DENV-3 (%) | DENV-4 (%) | ||

| DENV-1 | 20 (66.7) | 5 (4.6) | 8 (13.3) | 1 (16.7) | 34 (16.7) |

| DENV-2 | 2 (6.7) | 81 (75.0) | 15 (25.0) | 2 (33.3) | 100 (49.0) |

| DENV-3 | 7 (23.3) | 20 (18.5) | 36 (60.0) | 2 (33.3) | 65 (31.9) |

| DENV-4 | 1 (3.3) | 2 (1.9) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (2.4) |

| Total | 30 | 108 | 60 | 6 | 204 |

Multinomial logistic regression models were also developed for a subset of observations that had pre-infection PRNT values <10 for all serotypes (primary seroconversion) and for a subset that had pre-infection PRNT values ≥ 10 for at least one serotype (secondary seroconversion). Although this classification did not correspond exactly with definitions of primary and secondary infections according to IgM/IgG EIA (Table 3), it stratifies the performance of our model by pre-existing dengue antibody levels.

Table 3.

Pre-infection PRNT <10 vs. primary infections according to IgM/IgG ELISA

| Pre-infection PRNT | IgM/IgG ≥ 1.8 a (%) | IgM/IgG <1.8b (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| <10 for all serotypes | 4 (100) | 31 (15.5) | 35 (17.2) |

| ≥10 for at least 1 serotype | 0 (0) | 169 (84.5) | 169 (82.8) |

| Total | 4 | 200 | 204 |

primary infection

secondary infection

The model for 35 cases with primary seroconversion (Model C) identified the infecting serotype with 77.1% positive and 92.2% negative agreement with PCR (Table 4). The kappa value for these predictions was 0.656. A model for 169 cases with secondary seroconversion (Model D) had 66.9% positive and 89.0% negative agreement with PCR and a kappa of 0.456, which is similar to the validity of the model predictions based on all cases combined.

Table 4.

Evaluation of model predictions. Three separate models were fit. One using all cases, one using only “primary seroconversions” and one using only “secondary seroconversions”.

| Validity | Using pre- and post-season PRNT | Using post season PRNT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| all cases (Model A) | primary seroconversions (Model C) | secondary seroconversions (Model D) | all cases (Model B) | |

| N | 204 | 35 | 169 | 204 |

| Positive agreement | 67.6 | 77.1 | 66.9 | 60.3 |

| Negative agreement | 89.2 | 92.3 | 89.0 | 86.8 |

| Kappa statistic | 0.479 | 0.656 | 0.456 | 0.292 |

In many epidemiologic studies, only post-infection PRNT values are available. We applied a multinomial logistic regression model that used only post-infection PRNT values to identify the currently infecting serotype (Model B). Predictions by this model had 60.3% positive and 86.8% negative agreement with PCR and a kappa value of 0.292. This reflects the performance of our model when pre-infection specimens are not available.

Finally, the evaluation of model predictions was stratified by the difference in probabilities between the serotype with the maximum and second highest model probability. As this difference increased, predictions became more accurate (Table 5). The percent positive agreement increased from 50.0% at a probability difference of ≤ 0.1 to 86.0% at a difference of 0.9–1.0. The percent negative agreement increased from 83.3% to 95.3% and kappa values increased from 0.010 to 0.681.

Table 5.

Evaluation of predictions stratified by difference in probabilities.

| Probability difference | N | % Positive agreement | % Negative agreement | Kappa statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 0.1 | 14 | 50.0 | 83.3 | 0.010 |

| 0.1 – 0.2 | 21 | 52.4 | 84.1 | 0.266 |

| 0.2 – 0.3 | 17 | 58.8 | 86.3 | 0.380 |

| 0.3 – 0.4 | 19 | 63.2 | 87.8 | 0.351 |

| 0.4 – 0.5 | 16 | 56.3 | 85.4 | 0.364 |

| 0.5 – 0.6 | 20 | 65.0 | 88.3 | 0.476 |

| 0.6 – 0.7 | 13 | 61.2 | 87.1 | 0.261 |

| 0.7 – 0.8 | 23 | 73.9 | 91.3 | 0.598 |

| 0.8 – 0.9 | 18 | 77.8 | 92.6 | 0.657 |

| 0.9 – 1.0 | 35 | 86.0 | 95.3 | 0.681 |

DISCUSSION

This is the first study that applied a statistical model to identify the serotype of a recent DENV infection using neutralizing antibody responses. We inferred the serotype of DENV infection based on pre- and post-infection PRNT values and compared model output to RT-PCR data obtained during the acute infection.

We found that our model correctly identified the infecting serotype in almost 70% of cases in our sample. This included primary as well as secondary seroconversions and almost no monotypic antibody responses. Model predictions could be stratified by reliability (Table 5), which could be used to obtain a model accuracy of >75% for one third of our sample This is better than expected based on previous literature [15, 19].

The most accurate predictions were made by model C for 35 cases that had undetectable pre-infection PRNT values (~77% positive agreement). Most of these cases had heterotypic antibody responses (97%) consistent with one previous exposure. This is in line with previous studies that used PRNT to infer the serotype of primary DENV seroconversions, although these were mostly restricted to monotypic antibody responses [14, 28, 29]. The application of this model is limited however to the small minority of primary DENV seroconversions. Model B only included post-infection PRNT values and would have the widest public health application. Despite using only part of the antibody profile, this model identified the infecting serotype correctly in ~60% of cases.

In general, the accuracy of model predictions depends on the patterns it can detect in antibody responses related to each PCR outcome. Due to the low number of children with DENV-4 infections, the model was not trained to accurately predict this serotype, implying that models should be developed for specific epidemiological situations.

Only four children (11%) with primary seroconversions had primary infections as determined by IgM/IgG EIA (Table 3). This EIA test has previously been demonstrated to accurately determine primary vs. secondary DENV infections [30]. In our sample however, prior JE vaccination or exposure to JE virus may have modified the IgM/IgG response [31]. Among the 35 children without detectable pre-infection PRNT, 74% of those who were classified as secondary infections by IgM/IgG had detectable PRNT antibodies against JE in pre-infection serum compared to none of those who were classified as primary infections (p=0.009, data not shown). More work will be needed to assess the potential influence of JE antibodies on IgM/IgG ratios for DENV.

We also tested more simplistic algorithms for inference on the serotype of past infection by selecting the serotype with the largest difference between pre- and post infection PRNT or the serotype with the highest post-infection PRNT as the infecting serotype (data not shown). Although such algorithms have been applied previously to primary seroconversions or monotypic antibody responses [13–15, 21], the validity of these algorithms in our sample was worse than any of our models (positive agreement of 32–44%), indicating that for inference on the serotype of DENV infections based on heterotypic PRNT responses, a multinomial model should be used.

The sensitivity and specificity of the neutralizing antibody response is compromised by cross-reactivity between the four DENV serotypes [32, 33]. Previous studies found that antibodies are directed against epitopes of DENV proteins that are shared among serotypes, allowing these antibodies to also neutralize serotypes that were not originally targeted [7, 10, 32]. Other research demonstrated that in sequential DENV infections, antibody levels may be highest against the initial infecting serotype due to a stronger response of already primed B- and T-cells (original antigenic sin) [34–36]. So far these factors have compromised the use of PRNT for inference on infecting DENV serotypes. Multinomial models could reduce this limitation of PRNT. WHO guidelines on performance and interpretation of the PRNT assay recommend 90% plaque reduction neutralization assays for epidemiological studies or diagnostic purposes over the 50% PRNT to reduce the effects of cross-reactivity [37]. The use of 90% PRNT may improve inference on infecting serotypes by multinomial models but may also result in more false negatives due to a higher cutoff level.

A negative PCR result was obtained in 82 cases (27%) that had serological evidence of DENV infection. Even though PCR tests were done within 6 days of the onset of symptoms, detection rates can decrease to 63–70% after 5 days [38, 39]. It is likely that negative PCR results in our sample resulted from blood samples that were taken toward the end of the 6 day spectrum.

Our post-infection serum samples were collected ~4 months after infections were detected by PCR. The time interval separating infections and sample collection for the PRNT may be an important determinant of model performance with higher accuracy for longer time intervals during which the antibody response becomes more monotypic [40]. It is possible that during this interval a number of children in our study were exposed to DENV. Previous work has demonstrated that this would unlikely result in clinical disease [41], but it would have altered the antibody pattern without knowledge of the serotype of exposure. It is unlikely however that such undetected exposures would have introduced any systematic error in our model.

A serological assay that could detect past seroconversions for particular DENV serotypes would be of great utility to vaccine trials and epidemiological studies. Although new neutralization tests are being developed [7, 33], PRNT will probably remain one of the most important tests to measure serotype specific antibody levels in the near future. Currently, DENV serotypes can only be detected by PCR or virus isolation, depending on sampling shortly after onset of symptoms. Results from this study indicate that a combination of pre- and post-infection PRNT50 values could be used to infer the serotype of recent DENV infections. Studies would need to weigh the known inaccuracy of using PRNT for the determination of DENV serotypes against the added sample size afforded by the ability to include individuals who were not sampled during the viremic period.

As phase 3 trials of dengue vaccine candidates have started, standardization of PRNT and common definitions on its interpretation become more important [23]. Our model provides a step in identifying serotype-specific patterns in PRNT values that could be used to compose algorithms for the interpretation of PRNT results.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Van Panhuis, Burke and Cummings are financially supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Drs. Burke and Cummings are supported by the National Institutes of Health (1U01-GM070708). Dr. Cummings is supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01 TW008246-01) and a Career Award at the Scientific Interface from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. Financial support to Drs. Gibbons, Endy, Rothman and Nisalak, has been provided by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH P01 AI034533) and the US Military Infectious Disease Research Program.

Footnotes

The authors do not have any commercial or other associations that might pose a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer: “The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the official views of the NIH or US Department of Defense.”

An abstract of this manuscript was presented at the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 58th Annual Meeting in Washington DC on 19 November 2009 (Abstract number 32).

Contributor Information

Willem G Van Panhuis, Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh PA, USA.

Robert V Gibbons, Department of Virology, United States Army Medical Component, Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences, Bangkok, Thailand.

Timothy P Endy, Infectious Disease Division, Department of Medicine, State University of New York, Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, New York, USA.

Alan L Rothman, Center for Infectious Disease and Vaccine Research, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, Massachusetts, USA.

Anon Srikiatkhachorn, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Center for Infectious Diseases and Vaccine Research, Worcester, MA, USA.

Ananda Nisalak, Department of Virology, United States Army Medical Component, Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences, Bangkok, Thailand.

Donald S Burke, Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh PA, USA.

Derek AT Cummings, Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore MD, USA.

References

- 1.Halstead SB. Dengue. Lancet. 2007;370:1644–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61687-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitehead SS, Blaney JE, Durbin AP, Murphy BR. Prospects for a dengue virus vaccine. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:518–28. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyle JL, Harris E. Global spread and persistence of dengue. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008;62:71–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.163005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pediatric Dengue Vaccine Institute. Global burden of Dengue. Vol. 2009. Seoul, Korea: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephenson JR. Understanding dengue pathogenesis: implications for vaccine design. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:308–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monath TP. Dengue and yellow fever--challenges for the development and use of vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2222–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0707161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roehrig JT, Hombach J, Barrett AD. Guidelines for Plaque-Reduction Neutralization Testing of Human Antibodies to Dengue Viruses. Viral Immunol. 2008;21:123–32. doi: 10.1089/vim.2008.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russell PK, Nisalak A. Dengue virus identification by the plaque reduction neutralization test. J Immunol. 1967;99:291–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell PK, Nisalak A, Sukhavachana P, Vivona S. A plaque reduction test for dengue virus neutralization antibodies. J Immunol. 1967;99:285–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai CY, Tsai WY, Lin SR, et al. Antibodies to envelope glycoprotein of dengue virus during the natural course of infection are predominantly cross-reactive and recognize epitopes containing highly conserved residues at the fusion loop of domain II. J Virol. 2008;82:6631–43. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00316-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kochel TJ, Watts DM, Halstead SB, et al. Effect of dengue-1 antibodies on American dengue-2 viral infection and dengue haemorrhagic fever. Lancet. 2002;360:310–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09522-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilder-Smith A, Foo W, Earnest A, Sremulanathan S, Paton NI. Seroepidemiology of dengue in the adult population of Singapore. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:305–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham RR, Juffrie M, Tan R, et al. A prospective seroepidemiologic study on dengue in children four to nine years of age in Yogyakarta, Indonesia I. studies in 1995–1996. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:412–9. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burke DS, Nisalak A, Johnson DE, Scott RM. A prospective study of dengue infections in Bangkok. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;38:172–180. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sangkawibha N, Rojanasuphot S, Ahandrik S, et al. Risk factors in dengue shock syndrome: a prospective epidemiologic study in Rayong, Thailand. I. The 1980 outbreak. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;120:653–669. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Comach G, Blair PJ, Sierra G, et al. Dengue Virus Infections in a Cohort of Schoolchildren from Maracay, Venezuela: A 2-Year Prospective Study. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008 doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papaevangelou G, Halstead SB. Infections with two dengue viruses in Greece in the 20th century. Did dengue hemorrhagic fever occur in the 1928 epidemic? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1977;80:46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halstead SB. Etiologies of the experimental dengues of Siler and Simmons. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1974;23:974–82. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1974.23.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guzman MG, Kouri G. Dengue diagnosis, advances and challenges. Int J Infect Dis. 2004;8:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2003.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Endy TP, Nisalak A, Chunsuttitwat S, et al. Relationship of Preexisting Dengue Virus (DV) Neutralizing Antibody Levels to Viremia and Severity of Disease in a Prospective Cohort Study of DV Infection in Thailand. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:990–1000. doi: 10.1086/382280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Comach G, Blair PJ, Sierra G, et al. Dengue Virus Infections in a Cohort of Schoolchildren from Maracay, Venezuela: A 2-Year Prospective Study. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009;9:87–92. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hombach J, Cardosa MJ, Sabchareon A, Vaughn DW, Barrett AD. Scientific consultation on immunological correlates of protection induced by dengue vaccines report from a meeting held at the World Health Organization 17–18 November 2005. Vaccine. 2007;25:4130–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simasathien S, Thomas SJ, Watanaveeradej V, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a tetravalent live-attenuated dengue vaccine in flavivirus naive children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:426–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas SJ, Nisalak A, Anderson KB, et al. Dengue plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) in primary and secondary dengue virus infections: How alterations in assay conditions impact performance. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:825–33. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.08-0625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Endy TP, Chunsuttiwat S, Nisalak A, et al. Epidemiology of inapparent and symptomatic acute dengue virus infection: a prospective study of primary school children in Kamphaeng Phet, Thailand. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:40–51. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Endy TP, Nisalak A, Chunsuttiwat S, et al. Spatial and temporal circulation of dengue virus serotypes: a prospective study of primary school children in Kamphaeng Phet, Thailand. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:52–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szklo M, Nieto F. Epidemiology byond the basics. Sudbury MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pengsaa K, Limkittikul K, Luxemburger C, et al. Age-specific prevalence of dengue antibodies in Bangkok infants and children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:461–3. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181646d45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pengsaa K, Luxemburger C, Sabchareon A, et al. Dengue virus infections in the first 2 years of life and the kinetics of transplacentally transferred dengue neutralizing antibodies in thai children. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1570–6. doi: 10.1086/508492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Souza VA, Tateno AF, Oliveira RR, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of three ELISA-based assays for discriminating primary from secondary acute dengue virus infection. J Clin Virol. 2007;39:230–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makino Y, Tadano M, Saito M, et al. Studies on serological cross-reaction in sequential flavivirus infections. Microbiol Immunol. 1994;38:951–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1994.tb02152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teles FR, Prazeres DM, Lima-Filho JL. Trends in dengue diagnosis. Rev Med Virol. 2005 doi: 10.1002/rmv.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Putnak JR, de la Barrera R, Burgess T, et al. Comparative evaluation of three assays for measurement of dengue virus neutralizing antibodies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:115–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuno G, Gubler DJ, Oliver A. Use of Original Antigenic Sin Theory to Determine the Serotypes of Previous Dengue Infections. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:103–105. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(93)90444-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halstead SB, Rojanasuphot S, Sangkawibha N. Original antigenic sin in dengue. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:154–156. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1983.32.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mongkolsapaya J, Dejnirattisai W, Xu XN, et al. Original antigenic sin and apoptosis in the pathogenesis of dengue hemorrhagic fever. Nat Med. 2003;9:921–7. doi: 10.1038/nm887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization. Guidelines for plaque reduction neutralization testing of human antibodies to dengue viruses. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh K, Lale A, Eong Ooi E, et al. A prospective clinical study on the use of reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction for the early diagnosis of Dengue fever. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:613–6. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.060019. quiz 617–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huhtamo E, Hasu E, Uzcategui NY, et al. Early diagnosis of dengue in travelers: comparison of a novel real-time RT-PCR, NS1 antigen detection and serology. J Clin Virol. 47:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guzman MG, Alvarez M, Rodriguez-Roche R, et al. Neutralizing antibodies after infection with dengue 1 virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:282–6. doi: 10.3201/eid1302.060539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sabin AB. Research on dengue during World War II. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1952;1:30–50. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1952.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]