Abstract

Hepatitis B virus X protein (pX), implicated in hepatocarcinogenesis, induces DNA damage because of re-replication and allows propagation of damaged DNA, resulting in partial polyploidy and oncogenic transformation. The mechanism by which pX allows cells with DNA damage to continue proliferating is unknown. Herein, we show pX activates Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) in the G2 phase, thereby attenuating the DNA damage checkpoint. Specifically, in the G2 phase of pX-expressing cells, the checkpoint kinase Chk1 was inactive despite DNA damage, and protein levels of claspin, an adaptor of ataxia telangiectasia-mutated and Rad3-related protein-mediated Chk1 phosphorylation, were reduced. Pharmacologic inhibition or knockdown of Plk1 restored claspin protein levels, Chk1 activation, and p53 stabilization. Also, protein levels of DNA repair protein Mre11 were decreased in the G2 phase of pX-expressing cells but not with Plk1 knockdown. Interestingly, in pX-expressing cells, Mre11 co-immunoprecipitated with transfected Plk1 Polo-box domain, and inhibition of Plk1 increased Mre11 stability in cycloheximide-treated cells. These results suggest that pX-activated Plk1 by down-regulating Mre11 attenuates DNA repair. Importantly, concurrent inhibition of Plk1, p53, and Mre11 increased the number of pX-expressing cells with DNA damage entering mitosis, relative to Plk1 inhibition alone. By contrast, inhibition or knockdown of Plk1 reduced pX-induced polyploidy while increasing apoptosis. We conclude Plk1, activated by pX, allows propagation of DNA damage by concurrently attenuating the DNA damage checkpoint and DNA repair, resulting in polyploidy. We propose this novel Plk1 mechanism initiates pX-mediated hepatocyte transformation.

Keywords: Cell Cycle, Checkpoint Control, DNA Damage, Hepatitis Virus, p53, HBV X Protein, Mre11, Polo-like Kinase 1

Introduction

In response to replication stress, stalled replication forks and DNA re-replication, genome integrity is maintained by activating the DNA damage checkpoint thereby preventing cells with DNA damage from entering mitosis. An important sensor of replication stress is the ATR3 kinase (1), which phosphorylates various substrates (2), including Rad17 (3), H2AX (4), and the checkpoint kinase Chk1 (5). ATR-mediated Chk1 phosphorylation requires interaction of the adaptor protein claspin (6) with phosphorylated Rad17 (7). In turn, Chk1 phosphorylates Wee1/Myt1, which blocks entry into mitosis while also contributing to p53 activation (8). Therefore, claspin is required for maintenance of the DNA damage checkpoint (7, 9). Conversely, proteasomal degradation of claspin mediates recovery from genotoxic stress (10, 11). Proteosomal degradation of claspin is initiated by Plk1-mediated phosphorylation of claspin at a phosphodegron site (12), a key step in the termination of the DNA damage checkpoint (13). Premature termination of the DNA damage checkpoint leads to checkpoint adaptation (14) resulting in genomic instability and tumorigenesis (15). Although the mechanism of checkpoint adaptation in mammalian cells is not yet understood, checkpoint adaptation is defined as the ability of a cell to divide in the presence of DNA damage. Checkpoint adaptation was first described in yeast (16), requiring among other genes the polo-like kinase homolog CDC5 (17–19). In multicellular organisms, evidence for checkpoint adaptation is derived from studies using Xenopus extracts (14) and human cells with radiation-induced DNA damage (20, 21). In irradiated human cells, overexpression of Chk1 or depletion of Plk1 delayed exit from the DNA damage checkpoint (21), indicating that Plk1 has a role in checkpoint adaptation in mammalian cells.

Plk1 is an important regulator of entry and progression through mitosis. Plk1 expression progressively increases from S to M phases (22), becoming maximally active in mitosis (23). In conditions of DNA damage, Plk1 is inactivated upon ATM/ATR activation (24, 25). Upon completion of DNA repair, Plk1 mediates recovery from the DNA damage checkpoint by inducing proteasomal degradation of claspin (13). Studies support that Plk1 also regulates the function of p53 (26–28). Our recent studies have shown that Topors (29, 30), following phosphorylation by Plk1, suppresses p53 sumoylation in the absence of DNA damage, inducing instead ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of p53 (31).

In agreement with the role of Plk1 in regulating both entry and progression through mitosis (32) and p53 function (26–28, 31), clinical studies have shown that overexpression of Plk1 is linked to many types of human cancers (33, 34). Elevated expression of Plk1 also occurs in virus-induced cancers, e.g. HBV-mediated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), determined by microarray analyses of human liver tumors (35), as well as in cancers induced by human papillomavirus-type 16 (36, 37). In HPV-16 E7-expressing cells, claspin is degraded despite DNA damage; these cells display elevated levels of Plk1 protein (38). Depletion of Plk1 induces apoptosis in cancer cell lines but not normal cells (28, 39). Likewise, inhibition of Plk1 suppresses hepatocyte transformation mediated by the HBV X oncoprotein (40) indicating Plk1 could serve as a novel therapeutic target for HBV-HCC and other virally induced cancers. Significantly, Plk1 inhibitors are currently in clinical trials for various types of human cancers (41, 42). However, the mechanism by which Plk1 contributes to pX-mediated oncogenic transformation is not yet understood.

The HBV X protein is implicated in HCC pathogenesis (43, 44), acting as a weak oncogene (45) or a co-factor in hepatocarcinogenesis (46). pX is a multifunctional protein, essential for the viral life cycle (47). pX increases the activity of the cellular mitogenic Ras-RAF-MAPK, JNK, and p38 MAPK pathways (48), and it enhances transcription of select viral and cellular genes (43). Activation of the mitogenic pathways by pX deregulates hepatocyte gene expression. Depending on growth conditions, this deregulation results in either accelerated entry into the cell cycle (49) or apoptosis (50). pX mediates p53 apoptosis only when pX-expressing cells are challenged with additional sub-apoptotic signals such as growth factor deprivation (50, 51). In optimal growth factor conditions, pX-expressing cells do not undergo apoptosis but instead exhibit accelerated and unscheduled S phase entry, activation of the DNA damage checkpoint, and eventual progression to mitosis (49). Interestingly, in optimal growth conditions, pX expression promotes DNA re-replication-induced DNA damage by enhancing expression of replication initiation factors Cdt1 and Cdc6, while inhibiting expression of geminin, the negative regulator of re-replication (52). Intriguingly, despite DNA re-replication-induced DNA damage, these pX-expressing hepatocytes proceed through mitosis, propagate damaged DNA, and generate daughter cells that are partially polyploid (>4N DNA) (52). Partial polyploidy induced by pX results in oncogenic transformation (40). However, it is not understood why pX expression allows nontransformed hepatocytes with DNA damage to recover from the DNA damage checkpoint, escape apoptosis, and propagate DNA damage. We hypothesize that pX activates a cellular mechanism that allows premature termination of the DNA damage checkpoint and DNA repair, thereby leading to oncogenic transformation.

In this study, we utilize the immortalized hepatocyte 4pX-1 cell line (53), in which expression of pX is regulated via the Tet-Off expression system. We provide evidence that pX induces the activity of Plk1 in the G2 phase, although pX-expressing cells undergo re-replication-induced DNA damage. In turn, pX-activated Plk1 alleviates the DNA damage checkpoint and p53 apoptosis by inducing proteasomal degradation of claspin. Also, in the G2 phase, pX-activated Plk1 down-regulates the stability of Mre11, despite ongoing DNA damage. Concurrent inhibition of p53, Mre11, and Plk1 in the G2 phase increases the number of pX-expressing cells with DNA damage entering mitosis, in comparison with Plk1 inhibition alone. By contrast, inhibition or knockdown of Plk1 reduces pX-induced polyploidy and increases apoptosis. We conclude pX-mediated Plk1 activation in the G2 phase attenuates both the DNA damage checkpoint and DNA repair resulting in propagation of DNA damage and partial polyploidy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

The tetracycline-regulated pX-expressing 4pX-1 cell line was grown as described previously (53). pX expression was initiated by removal of tetracycline (53).

Construction of 4pX-1-Plk1kd Cell Lines

4pX-1 cells were stably transfected with shRNAmir for Plk1 in a retroviral vector derived from pGIPZ (Open Biosystems). Clonal 4pX-1-Plk1kd cell lines were isolated by puromycin (1.0 μg/ml) selection and screened by Western blot assays employing Plk1 antibody (Abcam). The 4pX-1-p38kd cell line was constructed similarly, as described in Ref. 51.

Cell Synchronization

Cells were synchronized by serum starvation or double thymidine block (52). Flow cytometry was performed as described previously (52).

The following reagents were used: nocodazole (300 ng/ml), Sigma; SB202190 (5.0 μm), Calbiochem; doxorubicin (0.5 μg/ml), Calbiochem; MG132 (2.5 μm), Sigma; BTO-1 (20 μm), Sigma; BI 2536 (0.5 μm), AxonMedChem; thymidine (2.0 mm), Sigma; cycloheximide (10 μg/ml), Sigma, and Mirin (100 μm), Enzo Life Sciences.

Western Blot Assays

Whole cell extracts or nuclear extracts were isolated from synchronized 4pX-1, 4pX-1-Plk1kd, or 4pX-1-p38kd cells after release from double thymidine block (DTB). Whole cell extracts (20 μg) prepared in RIPA buffer containing PBS, pH 7.4, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1.0% Nonidet P-40, 1.0 mm EDTA, 0.4 mm EGTA, 10% glycerol, 0.1% SDS, 1.0 mm PMSF, 1.0 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1.0 mm sodium orthovanadate, 5.0 mm glycerol phosphate, and 10 mm sodium fluoride were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Nuclear extracts were prepared employing the nuclear extract kit from Active Motif. The antibodies used were as follows: phospho-ATR Ser-428 (1:1000), ATR (1:1000), phospho-Chk1 Ser-345 (1:500), Chk1 (1:500), phospho-Rad17 Ser-645 (1:700), Rad17 (1:700), Cdc2 (1:1000), phospho-Cdc2 Tyr-15 (1:500) from Cell Signaling; claspin (1:250) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Plk1 (1:1000) from Abcam; actin (1:1000) from Sigma; p53 (1:1000) from Vector Laboratories; H2AX (1:1000), γ-H2AX Ser-139 (1:1000), and Mre11 (1:1000) from Calbiochem; ATM, phospho-Ser-1981-ATM (Calbiochem); and phospho-histone 3 (1:1000) from Millipore. Quantification was by Image J software.

Plk1 Immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed in buffer containing 20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 1.5 mm EDTA, 5.0 mm EGTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.5 mm sodium vanadate supplemented with phosphatase and proteinase inhibitors (20 mm p-nitrophenyl phosphate, 1.0 mm Pefabloc, 10 μg/ml pepstatin A, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 5.0 μg/ml aprotinin). Lysates (1.0 mg) were clarified for 30 min at 15,000 × g and incubated with 0.6 mg/ml anti-Plk1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog number sc-17783) overnight at 4 °C, followed by a 1-h incubation with protein A-Sepharose beads. Immunocomplexes were washed four times and resolved by SDS-PAGE.

Plk1 in Vitro Kinases Assays

Whole cell extract (0.2–1.0 mg) was incubated with 0.6 mg/ml anti-Plk1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog number, sc-17783) overnight at 4 °C. Plk1 immunocomplex was recovered by centrifugation at 4 °C. In vitro kinase assays were carried out as described previously (54–59) using 0.2–1.0 μg of recombinant topoisomerase II fragment (amino acids 1259–1350) as substrate (55) and [γ-32P]ATP. Reaction mixtures were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

Comet and immunofluorescence assays were performed as described previously (52). Statistical analysis was performed by Student's t test.

RESULTS

Plk1 Is Activated in G2 Phase of Immortalized pX-expressing Hepatocytes

Elevated protein levels of Plk1 occur in many human cancers (33, 34, 60), including HBV-mediated liver cancer (35). Plk1 also is elevated during pX-mediated hepatocyte transformation, and significantly, inhibition of Plk1 suppresses hepatocyte transformation by pX (40). However, the role of Plk1 in pX-induced oncogenic transformation is not yet understood. Accordingly, employing the immortalized pX-expressing 4pX-1 cell line (53), we examined whether pX activates Plk1. The 4pX-1 cell line, employed in our studies of pX function (40, 49–51, 53, 61, 62), is an immortalized hepatocyte cell line expressing pX via the Tet-Off system.

To determine whether pX mediates activation of Plk1, 4pX-1 cells were synchronized in G1/S by the DTB. Plk1 activity was examined by in vitro Plk1 immunocomplex kinase assays using lysates isolated from 4pX-1 cells grown with or without pX, in a time course after release from DTB. We have shown earlier that 10 h after release from DTB, 75–80% of pX-expressing 4pX-1 cells are in G2 phase (52). Furthermore, double immunostaining of 4pX-1 cells for BrdU incorporation (S phase) and p-H3 (M phase) confirmed that the majority of pX-expressing cells enter mitosis 11 h after release from DTB (Fig. 1B). Employing in vitro Plk1 immunocomplex kinase assays (54–59) with topoisomerase II fragment (amino acids 1259–1350) as substrate (55), we detected maximal Plk1 activity 8–10 h after release from DTB in the presence of pX expression. This interval after DTB release corresponds to the G2 phase (Fig. 1, A and B) (52). Quantification of Plk1 activity normalized to the same level of Plk1 protein shows that in G2 phase (10-h interval), pX-expressing cells exhibited a 5-fold induction in Plk1 activity (Fig. 1D). By contrast, in mitosis (11-h interval) Plk1 activity was nearly the same irrespective of pX expression.

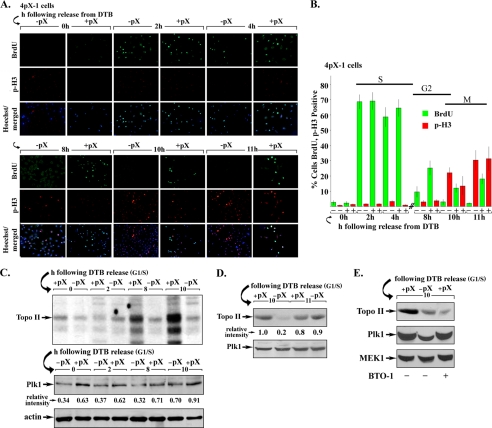

FIGURE 1.

pX activates Plk1. A, shown are 4pX-1 cells immunostained for BrdU incorporation and phospho-H3 (p-H3) in the indicated time course after release from DTB, with (+) or without (−) pX. pX expression was initiated by tetracycline removal 10 h before release from the second block and continued for the indicated time course. B, quantification of three independent experiments of BrdU-positive (green) and p-H3-positive (red) cells by ImageJ software, counting at least 1000 cells for each histogram (n = 3). C, in vitro Plk1 immunocomplex kinase assays using lysates isolated at the indicated times after DTB release. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with Plk1 antibody (54–59). Plk1 immunocomplex kinase assays (55) used recombinant topoisomerase II (Topo II) fragment spanning amino acids 1259–1350 as substrate and [γ-32P]ATP (n = 3). Immunoblots of Plk1 are shown below the kinase assay. Relative intensity quantified versus actin (n = 3). D, Plk1 in vitro immunocomplex kinase assays using lysates from 4pX-1 cells grown with (+) or without (−) pX for 10 and 11 h after release from DTB, normalized to Plk1 protein. Plk1 immunoblot is shown. E, in vitro Plk1 immunocomplex kinase assays with (+) or without (−) pX expression and BTO-1 (20 μm) addition as indicated, employing lysates isolated 10 h after release from DTB. BTO-1 was added 1 h prior to cell harvesting. Immunoblots of Plk1 and MEK1 (loading control) are shown.

To confirm the specificity of the Plk1 antibody (54–59) employed in our in vitro immunocomplex kinase assays, we used lysates from 4pX-1 cells treated with the Plk1-specific inhibitor BTO-1 (63). BTO-1 was added to 4pX-1 cells 1 h prior to cell harvesting, at 9 h after release from DTB. The in vitro kinase assays (Fig. 1E) demonstrate that BTO-1 treatment nearly abolished the in vitro phosphorylation of the recombinant topoisomerase II fragment (amino acids 1259–1350) used as the substrate (55). Accordingly, we conclude that pX mediates the activation of the Plk1 kinase in the G2 phase.

Recent studies have demonstrated that MK2, a downstream substrate of p38 MAPK, phosphorylates Plk1 at Ser-326 leading to Plk1 activation and mitotic progression (64). Because pX activates the p38 MAPK pathway in a sustained manner in 4pX-1 cells (50, 61), employing a 4pX-1-p38αkd (knockdown) cell line described in our earlier study (51), we quantified Plk1 activation as a function of pX expression. In the G2 phase of 4pX-1-p38αkd cells, pX-dependent activation of Plk1 was minimal (supplemental Fig. 1), suggesting that pX mediates activation of Plk1 via activation of the p38 MAPK pathway.

pX-mediated Activation of Plk1 Attenuates the DNA Damage Checkpoint

Plk1 mediates recovery from the DNA damage checkpoint by inducing proteasomal degradation of claspin (12). Claspin is required for maintenance of the DNA damage checkpoint, acting as an adaptor for ATR-mediated Chk1 phosphorylation (16). Because pX-expressing cells exhibit increased Plk1 activity in the G2 phase (Fig. 1) and propagate DNA damage to daughter cells (40, 52), we examined whether Plk1 deregulates the DNA damage checkpoint (Fig. 2A).

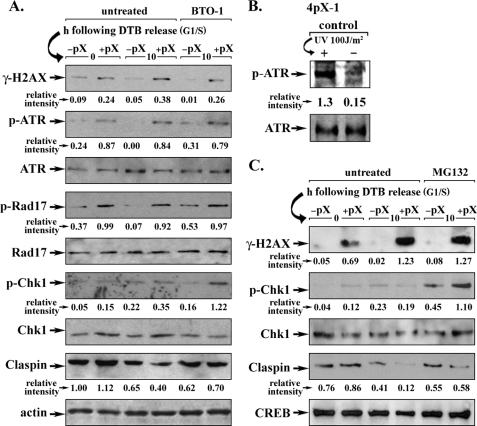

FIGURE 2.

pX-mediated Plk1 activation terminates the DNA damage checkpoint. A, 4pX-1 cells were synchronized in G1/S by DTB. pX was expressed by tetracycline removal at the beginning of the second block, continuing for 10 h after DTB release. Plk1 inhibitor BTO-1 (20 μm) was added 1 h prior to cell harvesting. Lysates were analyzed by immunoblots for the indicated molecules. Relative intensity is quantified versus actin (n = 3). B, immunoblots of lysates from 4pX-1 cells treated with UV light for ATR activation, using phospho-ATR Ser-428 antibody. C, nuclear extracts from 4pX-1 cells were isolated as in A, except MG132 (2.5 μm) was added 1 h prior to harvest. Lysates were analyzed by immunoblots for the indicated molecules. Relative intensity quantified versus cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB) used as loading control (n = 3).

Lysates from the G2 phase of pX-expressing 4pX-1 cells exhibited increased phosphorylation of the ATR substrates H2AX (γ-H2AX), an early marker of DNA damage (4), and Rad17 (3), as well as phosphorylation of ATR (Fig. 2A). The same ATR phosphorylation also was detected following UV irradiation of 4pX-1 cells (Fig. 2B). Intriguingly, despite the observed DNA damage in pX-expressing cells, Chk1 was not activated. In pX-expressing cells, activation of Chk1 was detected only after inhibition of Plk1 (Fig. 2A) by treatment with the Plk1 inhibitor BTO-1 (63). Furthermore, the protein level of claspin was reduced by nearly 40% in the G2 phase of pX-expressing cells, whereas inhibition of Plk1 by BTO-1 restored the protein levels of claspin. Importantly, inhibition of Plk1 also restored phosphorylation of Chk1, suggesting that Plk1 activation by pX overrides the DNA damage checkpoint, despite ongoing DNA damage.

Because Plk1 phosphorylation of claspin induces its proteasomal degradation, we treated 4pX-1 cells with the proteosome inhibitor MG132. The degradation of claspin and phosphorylation of Chk1 were restored following treatment with MG132 (Fig. 2C). These results demonstrate that in the G2 phase of pX-expressing cells, claspin is targeted for degradation by Plk1 despite the presence of DNA damage.

To verify by another approach that activation of Plk1 by pX attenuates the DNA damage checkpoint, we examined the status of the inhibitory phosphorylation of residue Tyr-15 of mitotic kinase Cdc2 (65). 10 h after release from DTB, pX-expressing cells exhibited the following: 1) γ-H2AX immunostaining indicative of DNA damage; 2) minimal p-H3 immunostaining as a marker of mitotic entry, and 3) phosphorylation of Tyr-15 of Cdc2 (Fig. 3A). The opposite was observed for cells not expressing pX. Inhibition of the proteasome by addition of MG132 or inhibition of Plk1 by treatment with another Plk1-specific inhibitor, BI 2536 (42), increased the inhibitory Y15-Cdc2 phosphorylation, delaying entry into mitosis, irrespective of pX expression (Fig. 3, A and B). Importantly, in pX-expressing cells, inhibition of Plk1 increased by an additional 50% the levels of the inhibitory Y15-Cdc2 phosphorylation and γ-H2AX (Fig. 3A), indicating that Plk1 activation by pX alleviates in part the DNA damage checkpoint of pX-expressing cells in the presence of DNA damage. More interestingly, 11 h after release from DTB, pX-expressing cells lacked the inhibitory Y15-Cdc2 phosphorylation despite the presence of DNA damage (γH2AX) and exhibited p-H3 immunostaining, indicating that they progressed to mitosis. By contrast, inhibition of the proteasome by MG132 or inhibition of Plk1 by BI 2536 maintained the inhibitory Y15-Cdc2 phosphorylation and suppressed progression to mitosis (Fig. 3, A and B). We interpret these results to mean that pX-expressing cells require Plk1 activation to proceed to mitosis in the presence of DNA damage.

FIGURE 3.

pX-mediated Plk1 activation activates mitotic Cdc2. A, nuclear extracts from 4pX-1 cells isolated at 10 and 11 h after release from DTB, with (+) or without (−) pX, immunoblotted for the indicated molecules. BI 2536 (0.5 μm) or MG132 (2.5 μm) was added 1 h prior to harvesting. Relative intensity for phosphorylated Y15-Cdc2 and p-H3 was quantified versus Cdc2 and H3, respectively (n = 3). B, 4pX-1 cells synchronized in G1/S by the DTB, immunostained for p-H3 in the indicated time course after release from the block, with (+) or without (−) pX expression. BI 2536 (0.5 μm) or MG132 (2.5 μm) was added 1 h prior to cell fixation. Histograms are quantifications of three independent experiments of p-H3-positive cells by ImageJ software, counting at least 500 cells for each histogram (n = 3).

Plk1 Knockdown Abrogates Claspin Degradation and Reduces DNA Damage in pX-expressing Immortalized Hepatocytes

To demonstrate by another approach that Plk1 deregulates the DNA damage checkpoint of pX-expressing cells, Plk1 knockdown cell lines were constructed in the 4pX-1 cellular background (4pX-1-Plk1kd) by stable integration of the pGIPZ vector, containing a Plk1 silencing sequence. Immunoblots confirmed the diminished level of Plk1 in clones 1 and 2 (Fig. 4A). Cell cycle progression of 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells was monitored after release from DTB by double immunostaining for BrdU incorporation (S phase) and p-H3 (M phase), as well as by flow cytometry (supplemental Fig. 2, A–C). 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells required nearly 20 h after DTB release to reach mitosis. By contrast, the 4pX-1-GIPZ control cell line progressed through the cell cycle at the same rate as 4pX-1 cells.

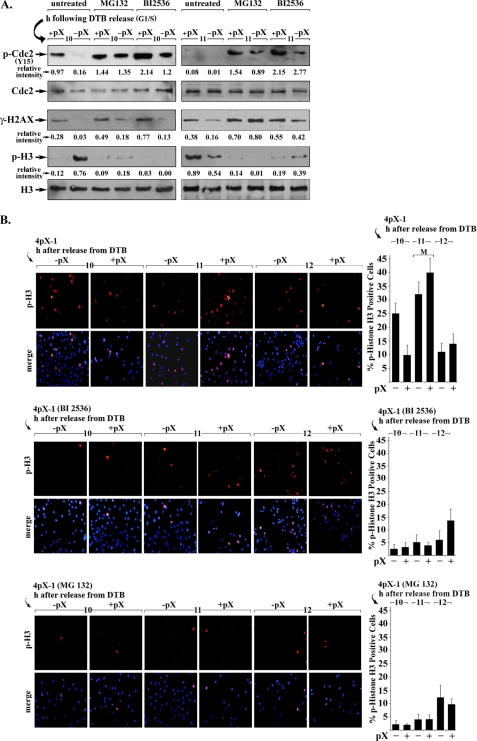

FIGURE 4.

Plk1 knockdown restores checkpoint activation in G2 phase of pX-expressing cells. A, Plk1 immunoblots using lysates from 4pX-1(GIPZ) and Plk1 knockdown cell lines (4pX-1-Plk1kd clones 1 and 2). 4pX-1-Plk1kd cell lines were constructed by stable integration of pGIPZ vector containing Plk1 silencing sequence. Actin is loading control. B, immunoblots with indicated antibodies were performed using nuclear extracts from 4pX-1-Plk1kd clones 1 and 2 isolated 16 and 20 h after DTB release. pX was expressed by tetracycline removal at the beginning of the second block, continuing for 16 and 20 h after DTB release. Relative intensity is quantified versus cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB). Cell cycle progression of 4pX-1-Plk1kd clone 1 and 2 following DTB release is shown in supplemental Fig. 2. C, agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products using RNA isolated from 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells and primers for pX or GAPDH (40). Cells were grown for the indicated time course after DTB release with (+) or without (−) addition of 5.0 μg/ml tetracycline.

Employing nuclear extracts of 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells, isolated at 16 and 20 h after release from DTB, we monitored by immunoblots the levels of γ-H2AX, phospho-Chk1, and claspin, as a function of pX expression (Fig. 4B). In the presence of pX, γ-H2AX was detected at 0 and 16 h after DTB release. Interestingly, at the 16-h interval after DTB release, pX-expressing 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells exhibited increased levels of phosphorylated Chk1 and claspin, indicating that the DNA damage checkpoint was active. As pX-expressing 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells progressed to the 20-h interval, phosphorylation of both H2AX and Chk1 decreased to a basal level, indicating that DNA damage had been repaired, and the checkpoint was removed. Because these results contrast those of pX-expressing 4pX-1 cells (Fig. 2), we confirmed by PCR that expression of pX by tetracycline removal was maintained in 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells (Fig. 4C).

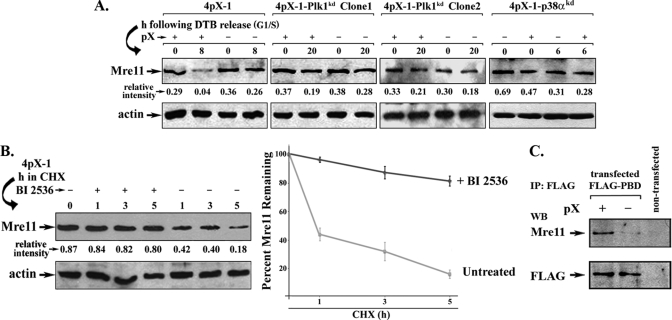

Plk1 Down-regulates the Protein Level of Mre11 in G2 Phase of pX-expressing Cells

The results of Fig. 4 demonstrate that 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells do not propagate DNA damage and suggest that Plk1 activation suppresses DNA repair and/or apoptosis. Importantly, during pX-mediated transformation (40), the protein levels of the DNA repair protein Mre11 (67) progressively decreased as Plk1 protein levels increased, suggesting Plk1 negatively regulates Mre11. To test this hypothesis, we examined protein levels of Mre11 in the G2 phase, as a function of pX expression.

A significant reduction in the protein level of Mre11 was observed in the G2 phase of pX-expressing 4pX-1 cells (Fig. 5A). By contrast, the level of Mre11 was nearly the same in the G2 phase of 4pX-1-Plk1kd and 4pX-1-p38αkd cells, irrespective of pX expression (Fig. 5A). This reduction in the level of Mre11 in pX-expressing 4pX-1 cells was reversed by inhibition of Plk1 or inhibition of the proteasome (data not shown), suggesting that Mre11 undergoes proteasomal degradation in the presence of activated Plk1. To investigate whether Plk1 regulates the stability of Mre11, we analyzed the level of Mre11 in cycloheximide-treated cells, with or without inhibition of Plk1 by addition of BI 2536 (Fig. 5B). In pX-expressing cells, the protein level of Mre11 was reduced by nearly 80% within 5 h following inhibition of protein synthesis, whereas inhibition of Plk1 greatly stabilized Mre11.

FIGURE 5.

Plk1 negatively regulates the stability of Mre11 in pX-expressing cells. A, immunoblots of Mre11 and actin (loading control) using lysates from 4pX-1, 4pX-1-Plk1kd, and 4pX-p38αkd cells with (+) or without (−) pX expression, harvested at 8, 20, and 6 h, respectively, after DTB release. Quantification of relative intensity is versus actin (n = 3). B, left panel, immunoblot of Mre11 and actin from lysates of 4pX-1 cells treated with doxorubicin (0.5 μg/ml) for 2 h. Following removal of doxorubicin, 10 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) was added for the indicated time course, with (+) or without (−) addition of BI 2536 (0.5 μm), in the presence of pX expression. Right panel, quantification of Mre11 protein levels from Mre11 immunoblots. C, immunoblots of Mre11 using FLAG immunoprecipitates (IP) from lysates of 4pX-1 cells transfected or not with FLAG-PBD expression vector, with (+) or without (−) pX expression. WB, Western blot.

Plk1 substrates interact directly with the PBD of Plk1 (68). Employing transient transfection of plasmid DNA encoding the PBD of Plk1 in fusion with the FLAG epitope (Fig. 5C), we observed increased co-immunoprecipitation of Mre11 in the presence of pX expression, suggesting that Mre11 is a Plk1 substrate.

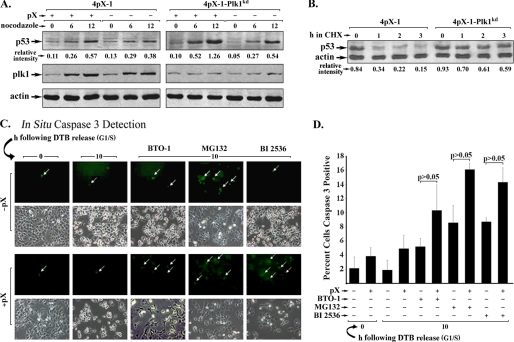

Plk1 Suppresses p53-mediated Apoptosis in G2 Phase of pX-expressing Immortalized Hepatocytes

In nontransformed pX-expressing 4pX-1 cells (52) and in hepatocytes undergoing pX-mediated transformation (40), re-replication-induced DNA damage is propagated to daughter cells resulting in polyploidy. It is intriguing that pX-expressing cells with DNA damage do not undergo apoptosis but proceed instead to mitosis (52). Remarkably, during pX-mediated hepatocyte transformation, an inverse relationship exists between Plk1 and p53 protein levels (40). Thus, we investigated whether Plk1 suppressed p53 function in immortalized 4pX-1 cells. First, we compared the protein levels of p53 in 4pX-1 and 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells as a function of pX expression, using cells arrested in G2/M by nocodazole treatment (Fig. 6A). The level of p53 increased by nearly 2-fold in pX-expressing 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells compared with 4pX-1 cells, indicating that Plk1 negatively regulates the protein level of p53. Similarly, in cycloheximide-treated 4pX-1 and 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells, the stability of p53 was significantly increased with Plk1 knockdown (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Plk1 suppresses p53-mediated apoptosis in G2 phase of pX-expressing cells. A, immunoblots of p53 using lysates isolated from 4pX-1 and 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells treated with nocodazole (300 ng/ml) for the indicated time course. Immunoblots of Plk1 are also shown (n = 3). B, immunoblots of p53 using lysates isolated from 4pX-1 and 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells treated with doxorubicin (0.5 μg/ml) for 2 h. Following removal of doxorubicin, 10 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) was added for the indicated time course, in the presence of pX expression. C, caspase 3 fluorescent substrate (Biocarta) was used to monitor apoptosis in 4pX-1 cells at 10 h following DTB release with (+) or without (−) pX expression, BTO-1 (20 μm), MG132 (2.5 μm), or BI 2536 (0.5 μm) added 2 h prior to harvest. D, quantification of caspase3-positive cells from C (n = 3).

To confirm these observations, we investigated whether inhibition of Plk1 leads to apoptosis by stabilizing p53. Accordingly, we quantified the percentage of apoptotic 4pX-1 cells using a fluorogenic caspase3 substrate (Fig. 6C). 4pX-1 cells, synchronized by DTB, were released for 10 h and grown as a function of pX expression; Plk1 inhibitors BTO-1 or BI 2536 and the proteosome inhibitor MG132 were added 1 h prior to cell harvest. The number of caspase3-positive cells in the presence of BTO-1, MG132, and BI 2536 increased (p < 0.05) in comparison with untreated cells (Fig. 6D), demonstrating that pX-mediated Plk1 activation suppresses p53 apoptosis in the nontransformed 4pX-1 cells.

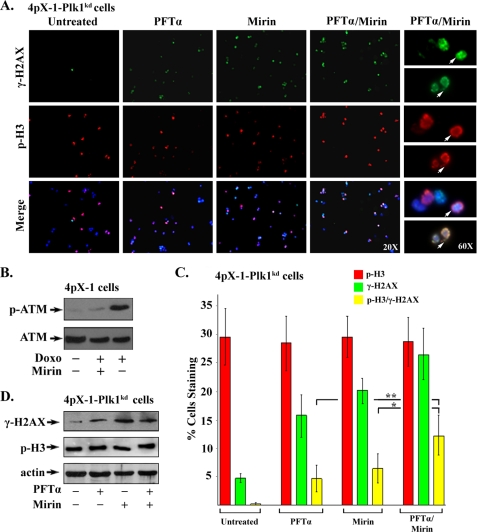

Inhibition of Both p53 and Mre11 Allows pX-expressing Plk1 Knockdown Cells to Enter Mitosis

Next, we investigated whether inhibition of both p53 apoptosis and DNA repair by Plk1 activation is necessary to allow pX-expressing cells with DNA damage to proceed to mitosis. We employed the Plk1 knockdown cell lines and inhibited p53 and Mre11 using the specific pharmacologic inhibitors PFT-α (69) and mirin (70), respectively. 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells were treated with PFT-α, mirin, or both, starting 16 h after DTB release in the presence of pX expression; cells were harvested at 22 h, the interval that corresponds to mitosis (supplemental Fig. 2B). Progression into mitosis in the presence of DNA damage was monitored by double immunostaining for γ-H2AX and p-H3 (Fig. 7A). Because the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 complex is required for activation of ATM (71), we confirmed by immunoblots monitoring phosphorylation of ATM on Ser-1981 the inhibition of Mre11 by 100 μm mirin (Fig. 7B). PFT-α was used at 10 μm, as described previously (51, 40). Next, we quantified the number of mitotic cells (p-H3-positive) co-staining with γ-H2AX in the presence of pX expression. Co-treatment with PFT-α and mirin increased by nearly 50% (p < 0.05) the number of pX-expressing cells entering mitosis in the presence of ongoing DNA damage, compared with PFT-α or mirin alone (Fig. 7C). Immunoblots of γ-H2AX and p-H3 using lysates following mitotic shake-off of 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells treated with PFT-α, mirin, or both confirmed the immunofluorescence results (Fig. 7D).

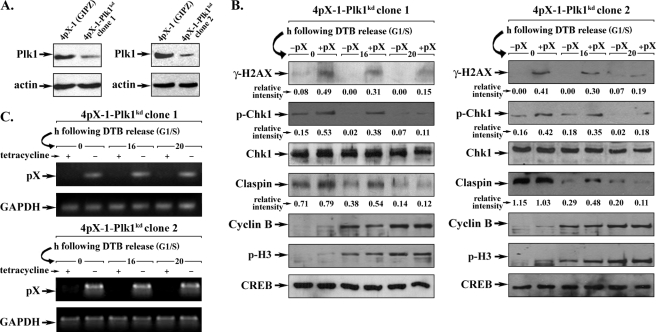

FIGURE 7.

A, inhibition of p53 and Mre11 allows Plk1 knockdown cells with DNA damage to enter mitosis. Immunofluorescence microscopy of 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells immunostained for γ-H2AX and p-H3 at 22 h after release from DTB, in the presence of pX expression. pX expression was initiated by tetracycline removal 10 h before release from the second block and continued for 22 h. PFT-α (10 μm), mirin (100 μm), or PFT-α plus mirin were added at 16 h after DTB release, the treatment continuing for 22 h. Images shown are ×20 and 60 magnification, as indicated (n = 3). B, immunoblots of p-Ser-1981 ATM using lysates from 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells treated with doxorubicin (Doxo) (0.5 μg/ml for 2 h) with (+) or without (−) addition of Mirin (100 μm). C, quantification of three independent experiments of γ-H2AX-positive (green) and p-H3-positive (red) cells from A, by ImageJ software, counting at least 500 cells for each histogram. Histogram in yellow indicates cells immunostaining with both markers. D, immunoblots of γ-H2AX and p-H3 using lysates from 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells treated with PFT-α (10 μm), mirin (100 μm), or PFT-α plus mirin; mitotic cells were isolated by mitotic shake-off at 22 h after DTB release.

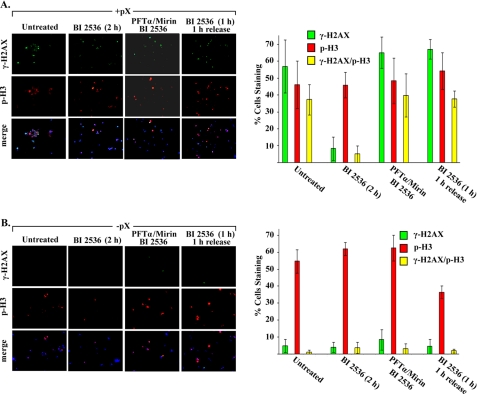

To further validate these results, we performed the same assay using the 4pX-1 cell line as a function of treatment with BI 2536 to inhibit Plk1 and pX expression (Fig. 8 and supplemental Fig. 3). Pharmacologic inhibition of p53, Mre11, and Plk1 was carried out 9–11 h after DTB release, spanning the G2 phase and mitosis. In pX-expressing cells (Fig. 8B), inhibition of Plk1 by BI 2536 addition for 2 h decreased to less than 10% the number of cells exhibiting DNA damage (γ-H2AX-positive). By contrast, inhibition of Plk1 as well as p53 and Mre11 increased by nearly 6-fold the number of γ-H2AX-positive cells and by 4-fold those that co-stain with p-H3, reaching the same level as untreated pX-expressing 4pX-1 cells. Likewise, 1 h release from BI 2536 inhibition rescued pX-expressing cells with DNA damage (γ-H2AX-positive) allowing entry into mitosis (p-H3-positive). In the absence of pX expression (Fig. 8A), DNA damage is minimal; concurrent inhibition of Plk1, p53, and Mre11 does not significantly increase DNA damage or the propagation of DNA damage to dividing cells.

FIGURE 8.

Inhibition of Plk1 suppresses propagation of DNA damage to dividing pX-expressing cells. Left panels, immunofluorescence microscopy of 4pX-1 cells immunostained for γ-H2AX and p-H3, 11 h after release from DTB, with (A) or without (B) pX expression (×20 magnification). pX expression was initiated by tetracycline removal 10 h before release from the second block and continued for 11 h. Indicated inhibitors were added 2 h prior to cell harvesting or were removed 1 h prior to cell harvesting. (See also supplemental Fig. 3.) Right panels, quantification from three independent experiments of γ-H2AX-positive (green) and p-H3-positive (red) cells. At least 200 cells were counted for each histogram. Histogram in yellow indicates cells immunostaining with both markers.

Plk1 Activated by pX Induces Polyploidy in Immortalized Hepatocytes

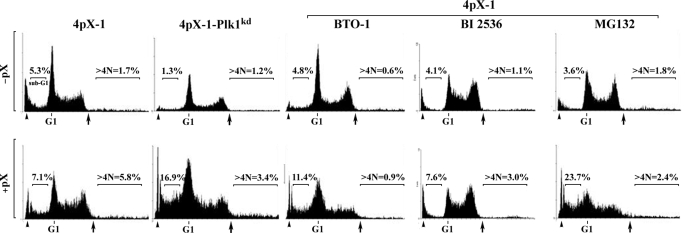

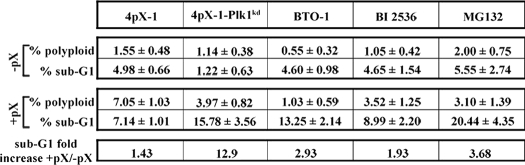

Because Plk1 activity increases the number of pX-expressing cells with DNA damage entering mitosis (Figs. 7 and 8), we examined whether pX-mediated Plk1 activation results in polyploidy.

Employing flow cytometry, we quantified the percent of apoptotic cells (sub-G1 peak) and those with more than 4N DNA (Fig. 9 and Table 1). The sub-G1 population increased 1.4-fold in pX-expressing 4pX-1 cells. By contrast, in pX-expressing 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells, the sub-G1 population increased 13-fold, indicating that diminished levels of Plk1 enhanced apoptosis. Furthermore, inhibition of Plk1 in 4pX-1 cells by addition of BTO-1 or BI 2536 or Plk1 knockdown in 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells reduced by at least 50% the number of pX-induced polyploid cells, those with more than 4N DNA content (Table 1). Likewise, MG132 treatment in 4pX-1 cells increased the apoptotic cells and decreased the pX-induced polyploid cell population (Fig. 9 and Table 1). We interpret these results to indicate that pX-mediated activation of Plk1 in nontransformed hepatocytes promotes generation of polyploidy by suppressing apoptosis.

FIGURE 9.

Loss of Plk1 function induces apoptosis, suppressing pX-induced polyploidy. Flow cytometric profiles of 4pX-1 treated with BTO-1, MG132, and BI 2536 as indicated or untreated 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells, with (+) or without (−) pX expression. Arrowhead indicates chick erythrocytes used for calibration. Arrows indicate end of the G2 symmetrical peak, used for quantification of cells with >4N DNA. Numbers shown indicate the percent of cells in the sub-G1 and >4N DNA cell populations (n = 3).

TABLE 1.

Quantification of indicated parameters from flow cytometric profiles shown in Fig. 9

DISCUSSION

The HBV X protein induces oncogenic transformation of hepatocytes by a mechanism that requires the activity of Plk1 (40). In this study, we report the following new results regarding the role of Plk1 in nontransformed pX-expressing hepatocytes, applicable to the mechanism of pX-mediated transformation. (i) The HBV X protein mediates activation of Plk1 in the G2 phase of untransformed hepatocytes (Fig. 1). Plk1 activation involves activation of the p38 MAPK pathway by pX (supplemental Fig. 1). The p38 MAPK pathway, required for mitotic entry (66), exhibits sustained activation in response to pX expression (61).

(ii) Plk1 activation attenuates the DNA damage checkpoint of pX-expressing nontransformed hepatocytes (Figs. 2 and 3). Our earlier studies have demonstrated that in 4pX-1 cells, pX promotes DNA re-replication-induced DNA damage and propagation of damaged DNA to the subsequent cell generations (40, 52) by an unknown mechanism. Here, we demonstrate that this mechanism of propagation of DNA damage involves activation of Plk1 by pX. It is well established that Plk1 induces degradation of claspin (Fig. 2), an adaptor protein of Chk1 activation by ATR (6), thereby mediating checkpoint recovery following termination of DNA repair (12, 14, 21). In pX-expressing cells, the novel aspect of this mechanism is that claspin degradation occurs despite the presence of DNA damage (Fig. 2A), and pX-expressing cells with DNA damage enter mitosis (Fig. 3B). Inhibition of Plk1 or the proteosome (Fig. 2, A and B) restored the protein level of claspin and the activation of Chk1. We confirmed these observations by assessing the activation status of the mitotic Cdc2 kinase. Specifically, inhibition of Plk1 in the G2 phase of pX-expressing cells inhibited activation of Cdc2 (Fig. 3A). By contrast, in the absence of Plk1 inhibition, pX-expressing cells activate Cdc2 and progress to mitosis even in the presence of DNA damage (Fig. 3A). Use of the 4pX-1-Plk1kd cell lines further confirmed these results. Specifically, Plk1 knockdown cells that express pX and experience DNA damage maintain the protein levels of claspin and the activation of Chk1 (Fig. 4B). Similar to our observations with the HBV X protein, attenuation of the DNA damage checkpoint and claspin degradation also occurs in HPV-16 E7-expressing cells; these cells continue to proliferate in the presence of DNA damage (38). However, depletion of claspin by shRNA was shown (20) to be insufficient for entry into mitosis of cells with irradiation-induced DNA damage, indicating that Plk1 deregulates additional targets.

(iii) Interestingly, our studies have identified a novel function of Plk1 in the G2 phase of pX-expressing cells, namely the down-regulation of Mre11, a component of the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 DNA repair complex (Fig. 5). The evidence in support of this conclusion is as follows. 1) The protein levels of Mre11 were reduced in the G2 phase of pX-expressing 4pX-1 cells but not in Plk1 or p38 MAPK knockdown cells (Fig. 5A). 2) The rate of Mre11 degradation was reduced by inhibition of Plk1 (Fig. 5B). 3) In pX-expressing cells, Mre11 co-immunoprecipitated with the PBD of Plk1 (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these results suggest that Mre11 is a potential Plk1 substrate, and pX, by activating Plk1, down-regulates Mre11 and DNA repair. Further studies are needed to establish that Mre11 is a Plk1 substrate.

(iv) Plk1 activated in the G2 phase rescues nontransformed pX-expressing hepatocytes with DNA damage from p53-mediated apoptosis. In our earlier study (52), we quantified that 15–20% of pX-expressing 4pX-1 cells in G2/M co-stained with BrdU and p-H3, indicative of cells with re-replication-induced DNA damage progressing to mitosis. Here, we show that 10–14% of pX-expressing 4pX-1 cells in the G2 phase (Fig. 6) undergo apoptosis following inhibition of Plk1 or the proteasome. We interpret these results to mean that inhibition of Plk1 in the G2 phase induces p53 apoptosis only of pX-expressing cells with DNA damage. In support of the role of Plk1 in pX-mediated p53 apoptosis, we show that the stability of p53 was increased in 4pX-1-Plk1kd cells (Fig. 6, A and B). The mechanism by which Plk1 regulates the stability of p53 in the presence of DNA damage likely involves not only Chk1 activation but also effects of Plk1 on molecules that directly modulate p53 stability (31). For example, Topors, a p53 small ubiquitin-related modifier and ubiquitin E3 ligase (29, 30), is a Plk1 substrate (31). Plk1-mediated phosphorylation of Topors suppresses p53 sumoylation in the absence of DNA damage, inducing instead ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of p53 (31).

(v) Syljuåsen (20) raised the question whether Plk1-induced claspin degradation and Chk1 inactivation are sufficient for checkpoint adaptation in mammalian cells. Our results (Fig. 7) show that in Plk1 knockdown cells, concurrent inhibition of p53, the end point of the DNA damage checkpoint, and the DNA repair protein Mre11 significantly increased the number of pX-expressing cells that enter mitosis in the presence of ongoing DNA damage. Conversely, in 4pX-1 cells, inhibition of Plk1 significantly decreased the number of X-expressing cells with DNA damage (γ-H2AX-positive) and also those co-staining with γ-H2AX and p-H3 (Fig. 8). We interpret these results to indicate that in the absence of Plk1 activity, DNA damage is repaired, and cells with unrepaired DNA damage undergo apoptosis. This interpretation agrees with the increased apoptosis of 4pX-1 cells and the reduction in pX-induced polyploidy by Plk1 inhibition (Fig. 9 and Table 1).

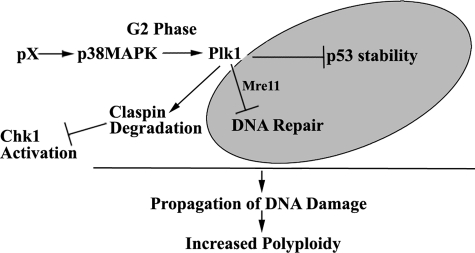

In summary, our studies provide evidence for a novel mechanism (Fig. 10) mediated by Plk1 activation in response to pX expression in nontransformed hepatocytes, namely pX-mediated Plk1 activation in the G2 phase concurrently attenuates the DNA damage checkpoint and DNA repair, thereby propagating DNA damage to dividing cells. We conclude Plk1 activation by pX is an initiating event in the propagation of DNA damage, resulting in polyploidy and eventual oncogenic transformation. We propose that pX-mediated Plk1 activation contributes to HBV-HCC pathogenesis. Moreover, this molecular mechanism (Fig. 10) mediated by Plk1 activation in response to the viral oncoprotein pX satisfies the following criteria for checkpoint adaptation as described by Toczyski et al. (19). 1) Arrested cell cycle due to DNA damage as shown in Fig. 3. 2) Attenuation of the DNA damage checkpoint, as shown in Figs. 2 and 3. 3) Continued proliferation despite DNA damage (Figs. 3A and 7–9). Similar to checkpoint adaptation in yeast, which requires Cdc5 (19), in mammalian cells, Plk1 activated by the viral pX mediates inactivation of Chk1 via claspin degradation and suppresses both DNA repair and p53 apoptosis, thereby allowing propagation of DNA damage. We propose that this study provides the first example of checkpoint adaptation occurring in mammalian cells in response to expression of the HBV oncoprotein pX.

FIGURE 10.

In G2 phase, HBV pX mediates Plk1 activation by activating the p38 MAPK pathway. Activated Plk1 induces claspin degradation, which suppresses activation of Chk1 and p53 apoptosis. In addition, Plk1 promotes degradation of Mre11, suppressing DNA repair. We conclude activation of Plk1 by pX in nontransformed hepatocytes terminates the DNA damage checkpoint and suppresses p53 apoptosis and DNA repair, resulting in propagation of DNA damage and generation of polyploidy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge support of the Purdue University Cytometry Laboratory.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK044533 and CA135192 (to O. A.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–3.

- ATR

- ATM and Rad3-related protein

- ATM

- ataxia telangiectasia-mutated

- HBV

- hepatitis B virus

- pX

- X protein

- PBD

- Polo-box domain

- DTB

- double thymidine block

- HCC

- hepatocellular carcinoma.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham R. T. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 2177–2196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuoka S., Ballif B. A., Smogorzewska A., McDonald E. R., 3rd., Hurov K. E., Luo J., Bakalarski C. E., Zhao Z., Solimini N., Lerenthal Y., Shiloh Y., Gygi S. P., Elledge S. J. (2007) Science 316, 1160–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bao S., Tibbetts R. S., Brumbaugh K. M., Fang Y., Richardson D. A., Ali A., Chen S. M., Abraham R. T., Wang X. F. (2001) Nature 411, 969–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward I. M., Chen J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 47759–47762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao H., Piwnica-Worms H. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 4129–4139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumagai A., Dunphy W. G. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 839–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X., Zou L., Lu T., Bao S., Hurov K. E., Hittelman W. N., Elledge S. J., Li L. (2006) Mol. Cell 23, 331–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor W. R., Stark G. R. (2001) Oncogene 20, 1803–1815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chini C. C., Chen J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 30057–30062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mailand N., Bekker-Jensen S., Bartek J., Lukas J. (2006) Mol. Cell 23, 307–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peschiaroli A., Dorrello N. V., Guardavaccaro D., Venere M., Halazonetis T., Sherman N. E., Pagano M. (2006) Mol. Cell 23, 319–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mamely I., van Vugt M. A., Smits V. A., Semple J. I., Lemmens B., Perrakis A., Medema R. H., Freire R. (2006) Curr. Biol. 16, 1950–1955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Vugt M. A., Brás A., Medema R. H. (2004) Mol. Cell 15, 799–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoo H. Y., Kumagai A., Shevchenko A., Shevchenko A., Dunphy W. G. (2004) Cell 117, 575–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Löbrich M., Jeggo P. A. (2007) Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 861–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandell L. L., Zakian V. A. (1993) Cell 75, 729–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee S. E., Moore J. K., Holmes A., Umezu K., Kolodner R. D., Haber J. E. (1998) Cell 94, 399–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paulovich A. G., Armour C. D., Hartwell L. H. (1998) Genetics 150, 75–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toczyski D. P., Galgoczy D. J., Hartwell L. H. (1997) Cell 90, 1097–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Syljuåsen R. G. (2007) Oncogene 26, 5833–5839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Syljuåsen R. G., Jensen S., Bartek J., Lukas J. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 10253–10257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golsteyn R. M., Mundt K. E., Fry A. M., Nigg E. A. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 129, 1617–1628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamanaka R., Smith M. R., O'Connor P. M., Maloid S., Mihalic K., Spivak J. L., Longo D. L., Ferris D. K. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 21086–21091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smits V. A., Klompmaker R., Arnaud L., Rijksen G., Nigg E. A., Medema R. H. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 672–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Vugt M. A., Smits V. A., Klompmaker R., Medema R. H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 41656–41660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ando K., Ozaki T., Yamamoto H., Furuya K., Hosoda M., Hayashi S., Fukuzawa M., Nakagawara A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 25549–25561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J., Dai G., Wang Y. Q., Wang S., Pan F. Y., Xue B., Zhao D. H., Li C. J. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580, 3624–3630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu X., Lei M., Erikson R. L. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 2093–2108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin L., Ozaki T., Takada Y., Kageyama H., Nakamura Y., Hata A., Zhang J. H., Simonds W. F., Nakagawara A., Koseki H. (2005) Oncogene 24, 3385–3396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajendra R., Malegaonkar D., Pungaliya P., Marshall H., Rasheed Z., Brownell J., Liu L. F., Lutzker S., Saleem A., Rubin E. H. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36440–36444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang X., Li H., Zhou Z., Wang W. H., Deng A., Andrisani O., Liu X. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 18588–18592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Vugt M. A., Medema R. H. (2005) Oncogene 24, 2844–2859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eckerdt F., Yuan J., Strebhardt K. (2005) Oncogene 24, 267–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takai N., Hamanaka R., Yoshimatsu J., Miyakawa I. (2005) Oncogene 24, 287–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen X., Cheung S. T., So S., Fan S. T., Barry C., Higgins J., Lai K. M., Ji J., Dudoit S., Ng I. O., Van De Rijn M., Botstein D., Brown P. O. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 1929–1939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Incassati A., Patel D., McCance D. J. (2006) Oncogene 25, 2444–2451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H., Jin Y., Chen X., Jin C., Law S., Tsao S. W., Kwong Y. L. (2007) Cancer Lett. 245, 184–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spardy N., Covella K., Cha E., Hoskins E. E., Wells S. I., Duensing A., Duensing S. (2009) Cancer Res. 69, 7022–7029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu X., Erikson R. L. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 8672–8676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Studach L. L., Rakotomalala L., Wang W. H., Hullinger R. L., Cairo S., Buendia M. A., Andrisani O. M. (2009) Hepatology 50, 414–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lénárt P., Petronczki M., Steegmaier M., Di Fiore B., Lipp J. J., Hoffmann M., Rettig W. J., Kraut N., Peters J. M. (2007) Curr. Biol. 17, 304–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steegmaier M., Hoffmann M., Baum A., Lénárt P., Petronczki M., Krssák M., Gürtler U., Garin-Chesa P., Lieb S., Quant J., Grauert M., Adolf G. R., Kraut N., Peters J. M., Rettig W. J. (2007) Curr. Biol. 17, 316–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andrisani O. M., Barnabas S. (1999) Int. J. Oncol. 15, 373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Su Q., Schröder C. H., Hofmann W. J., Otto G., Pichlmayr R., Bannasch P. (1998) Hepatology 27, 1109–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Terradillos O., Billet O., Renard C. A., Levy R., Molina T., Briand P., Buendia M. A. (1997) Oncogene 14, 395–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Madden C. R., Finegold M. J., Slagle B. L. (2001) J. Virol. 75, 3851–3858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zoulim F., Saputelli J., Seeger C. (1994) J. Virol. 68, 2026–2030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bouchard M. J., Schneider R. J. (2004) J. Virol. 78, 12725–12734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee S., Tarn C., Wang W. H., Chen S., Hullinger R. L., Andrisani O. M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 8730–8740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang W. H., Grégori G., Hullinger R. L., Andrisani O. M. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 10352–10365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang W. H., Hullinger R. L., Andrisani O. M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25455–25467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rakotomalala L., Studach L., Wang W. H., Gregori G., Hullinger R. L., Andrisani O. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 28729–28740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tarn C., Bilodeau M. L., Hullinger R. L., Andrisani O. M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 2327–2336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou T., Aumais J. P., Liu X., Yu-Lee L. Y., Erikson R. L. (2003) Dev. Cell 5, 127–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li H., Wang Y., Liu X. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 6209–6221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu Z. Q., Yang X., Weber G., Liu X. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25503–25513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu Z. Q., Liu X. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 1919–1924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang X., Li H., Liu X. S., Deng A., Liu X. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 28775–28782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu X. S., Li H., Song B., Liu X. (2010) EMBO Rep. 8, 626–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamada S., Ohira M., Horie H., Ando K., Takayasu H., Suzuki Y., Sugano S., Hirata T., Goto T., Matsunaga T., Hiyama E., Hayashi Y., Ando H., Suita S., Kaneko M., Sasaki F., Hashizume K., Ohnuma N., Nakagawara A. (2004) Oncogene 23, 5901–5911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tarn C., Zou L., Hullinger R. L., Andrisani O. M. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 9763–9772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tarn C., Lee S., Hu Y., Ashendel C., Andrisani O. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 34671–34680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peters U., Cherian J., Kim J. H., Kwok B. H., Kapoor T. M. (2006) Nat. Chem. Biol. 2, 618–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tang J., Yang X., Liu X. (2008) Oncogene 27, 6635–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.O'Connell M. J., Raleigh J. M., Verkade H. M., Nurse P. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 545–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cha H., Wang X., Li H., Fornace A. J., Jr. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 22984–22992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Toyoshima-Morimoto F., Taniguchi E., Nishida E. (2002) EMBO Rep. 3, 341–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee K. S., Grenfell T. Z., Yarm F. R., Erikson R. L. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 9301–9306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Murphy P. J., Galigniana M. D., Morishima Y., Harrell J. M., Kwok R. P., Ljungman M., Pratt W. B. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 30195–30201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dupré A., Boyer-Chatenet L., Sattler R. M., Modi A. P., Lee J. H., Nicolette M. L., Kopelovich L., Jasin M., Baer R., Paull T. T., Gautier J. (2008) Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 119–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee J. H., Paull T. T. (2004) Science 304, 93–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.