Abstract

Pocket proteins negatively regulate transcription of E2F-dependent genes and progression through the G0/G1 transition and the cell cycle restriction point in G1. Pocket protein repressor activities are inactivated via phosphorylation at multiple Pro-directed Ser/Thr sites by the coordinated action of G1 and G1/S cyclin-dependent kinases. These phosphorylations are reversed by the action of two families of Ser/Thr phosphatases: PP1, which has been implicated in abrupt dephosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein (pRB) in mitosis, and PP2A, which plays a role in an equilibrium that counteracts cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) action throughout the cell cycle. However, the identity of the trimeric PP2A holoenzyme(s) functioning in this process is unknown. Here we report the identification of a PP2A trimeric holoenzyme containing B55α, which plays a major role in restricting the phosphorylation state of p107 and inducing its activation in human cells. Our data also suggest targeted selectivity in the interaction of pocket proteins with distinct PP2A holoenzymes, which is likely necessary for simultaneous pocket protein activation.

Keywords: CDK (Cyclin-Dependent Kinase), Cell Cycle, Cellular Regulation, Cyclins, Phosphoprotein Phosphatase, Phosphorylation Enzymes, PP2A, Retinoblastoma (Rb), SV40 Small t Antigen, p107

Introduction

The retinoblastoma family of growth suppressor proteins, designated pocket proteins, includes the product of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene and the functionally and structurally related proteins p107 and p130 (reviewed in Ref. 1). Pocket proteins suppress the G0/G1 cell cycle transition and passage through the restriction point by repressing E2F-dependent transcription via a direct interaction of the hypophosphorylated pocket protein with members of the E2F family of transcription factors. Mitogen-dependent activation of D-type cyclin-CDK2 complexes cooperates with cyclin E-CDK2 complexes to hyperphosphorylate pocket proteins starting in mid-to late G1 disrupting the pocket protein-E2F interaction and relieving repression of many genes whose products are required for cell cycle progression. Pocket proteins remain hyperphosphorylated through the S and G2 phases and part of mitosis as they become targets of cyclin-CDK complexes that operate at these cell cycle stages (reviewed in Refs. 2–4).

As cyclin-CDK complexes are inactivated during mitotic exit, the three pocket proteins become simultaneously hypophosphorylated. PP1 has been implicated in dephosphorylation of pRB from mitosis to a point in G1, where pRB becomes hyperphosphorylated by G1 cyclin-CDKs (reviewed in Refs. 3 and 5). However, a second phosphatase plays a role in reversing the action of CDKs throughout the cell cycle and in quiescent cells (6). When the activity of cyclin-CDK complexes is pharmacologically inhibited, pocket proteins become rapidly dephosphorylated, and the severity of the hypophosphorylation depends on the subsets of CDKs that become inactivated. For instance, cycloheximide, an inhibitor of protein synthesis, causes rapid down-regulation of short lived cyclins such as D-type cyclins, resulting in potent dephosphorylation of p107, but only partial dephosphorylation of p130 and pRB, as CDK2 remains active for several hours. In contrast, treatment with the potent CDK inhibitor flavopiridol leads to rapid and complete dephosphorylation of pocket proteins as all CDKs become inactive (6).

PP2A, a second Ser/Thr phosphatase, has been implicated in dephosphorylation of pocket proteins throughout the cell cycle by using selective pharmacological inhibitors of PP2A in cells and in vitro, as well as by expressing in cells the Simian virus 40 (SV40) small t antigen (st), which binds and specifically inhibits PP2A (6). In addition, the catalytic subunit of PP2A was found to associate with both p130 and p107 through the cell cycle and in quiescent cells. Others have implicated PP2A in dephosphorylation of pocket proteins in response to a variety of signals including oxidative stress (7, 8), DNA damage (9), retinoic acid (10), UV radiation (11), and FGFα-mediated grow arrest in chondrosarcoma cells (12).

Although cells express a multitude of distinct protein kinases, many of them monomeric, that specialize in targeting selected substrates, the number of cellular proteins with catalytic phosphatase activity is small. Because many of the processes involving kinases also implicate phosphatases, it has been assumed that phosphatases play a passive role with limited specificity in the regulation of protein function. However, recent work has shown that PP2A, despite its ubiquitous nature, exhibits highly regulated substrate selectivity that is determined by association with multiple regulatory subunits (reviewed in Ref. 13). PP2A is a trimeric enzyme that consists of a catalytic subunit (PP2A/C), a scaffold subunit (PP2A/A), and a regulatory subunit (PP2A/B). Two genes for each PP2A/C and PP2A/A encode highly similar isoforms of these subunits. However, there are four families of B subunits (B, B′, B″, and striatins), each with several members encoded by genes with multiple splice variants that mediate substrate specificity and subcellular localization. Moreover, additional proteins can replace B subunits (14). Thus, it appears that in excess of 200 biochemically distinct PP2A holoenzymes can assemble with presumed distinct specificities (reviewed in Ref. 13).

Although we had previously implicated PP2A in modulating the phosphorylation state of pocket proteins as part of a dynamic equilibrium with CDKs throughout the cell cycle, the specific holoenzyme targeting pocket proteins in this scenario is unknown. We have used in vitro and cell-based assays to identify B55α as a regulatory subunit that assembles a PP2A trimeric complex that targets p107 and p130. A purified B55α trimeric holoenzyme specifically dephosphorylates p107 in vitro. Modulation of B55α expression in cells induces prominent changes in the phosphorylation of p107 and, to a lesser extent, p130, indicating that the levels of this subunit determine the overall phosphorylation state of these pocket proteins. Our data also show that different PP2A holoenzymes target particular pocket proteins as pRB appears to associate preferentially with PR70 rather than B55α. Importantly, a relatively small increase in B55α expression is sufficient to activate p107 but fails to induce growth arrest as the other pocket proteins remain mostly hyperphosphorylated. This suggests that multiple distinct PP2A holoenzymes target pocket proteins to coordinately induce their activation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Treatments

Human osteosarcoma U-2 OS cells and human glioblastoma T98G cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagles' medium (DMEM) (Cellgro) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gemini). Cells were grown under standard tissue culture conditions at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. T98G cells were made quiescent by serum starvation. Briefly, confluent T98G cells were reseeded in MCDB medium (Sigma) without FBS (∼2 × 106 cells/10-cm plate). Following 72 h of serum starvation, cells were restimulated with medium containing 10% serum as described previously (15). Cells were collected at the indicated time points and lysed as described below. Cell synchronization was monitored by propidium iodide staining followed by flow cytometric analysis.

Protein Expression and Analysis

All protein assays were conducted on ice or at 4 °C unless otherwise indicated. Protein extracts were prepared by lysing cells in DIP buffer (50 mm HEPES (pH 7.2), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 2.5 mm EGTA, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Tween 20, which was supplemented with freshly added 1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mm NaF, 0.5 mm Na3VO4, 2 mm PMSF, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 4 μg/ml aprotinin, and 4 μg/ml pepstatin) for 30 min and cleared by centrifugation. Western blot analysis and immunoprecipitations were performed essentially as described previously (6). 6% polyacrylamide/SDS gels were used to determine the phosphorylation state of pocket protein analysis, whereas 8–12% gels were used to assess protein expression. For immunoprecipitations, 200–300 μg of whole lysate (300 μl) were incubated overnight while rocking, with specific antibodies. For immunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins, we used ∼1 mg of whole protein lysate per antibody. In vitro binding assays were performed by incubating 2 μg of GST fusion proteins loaded onto glutathione beads with 300 μg of whole lysate or 1 μg of recombinant purified PP2A holoenzyme complexes in complete DIP buffer. Purified trimeric recombinant PP2A complexes containing B55α, PR48, or B56γ2 were prepared as described previously (16). Following incubation, the beads were washed 4–5 times with DIP buffer. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting.

Antibodies

Anti-p107 (sc-318), anti-pRB (sc-50), anti-HA (sc-805), anti-cyclin A (sc-596), anti-E2F4 (sc-512), anti-p27 (sc-528), anti-B55α (sc-33191), anti-CDK2 (sc-163) rabbit polyclonal antibodies; anti-PP2A/A (sc-6113) and anti-PR48 (sc-11801) goat polyclonal antibodies; and anti-HA (sc-7392) and anti-B55α (sc-81606) mouse monoclonal antibody were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-p130 (R27020) and anti-PP2A/C (1D6) and anti-pRB (G3–245) monoclonal antibodies were from BD Transduction Laboratories, Upstate Biotech Millipore, and BD Pharmingen, respectively. Anti-pan-B56 polyclonal antibody was from Stratagene. A monoclonal antibody that recognizes small t antigen (mAb-419) was a gift of Dr. E. Moran.

In Vitro Phosphatase Assays

Soluble histone H1 and GST-p107 loaded on glutathione beads were phosphorylated with purified cyclin A-CDK2 (Millipore) in kinase buffer (50 mm HEPES (pH 7.2), 10 mm MgCl2, 5 mm MnCl2) supplemented with 50 μm ATP and 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP for 1 h at 30 °C. GST-p107-loaded beads were washed four times in buffer containing 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.4) and 10 mm EDTA. Phosphorylated histone H1 was TCA-precipitated and redissolved in phosphatase buffer. Purified PP2A heterotrimers (1.5 μg, see above) were incubated with 3 μg of 32P-labeled GST-p107 or histone H1 substrates in phosphatase buffer (50 mm Tris (pH 7.6), 0.7 mg/ml BSA, 50 mm NaCl, 0.4 mm EDTA) at 30 °C for 30 min. Following incubation, GST-p107 beads were pelleted, and the supernatant was removed. The reaction was stopped by the addition of SDS-PAGE loading buffer and resolved on an 8% gel. Phosphatase reactions with histone H1 substrate were stopped by the direct addition of SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Substrates were detected via Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining, and substrate dephosphorylation was determined by exposure to x-ray film.

Plasmids

pECE-HA-pRB and pCMV-HA-p107 were gifts from Dr. R. Bernards (17). pCMV5 HA-B55α was a kind gift from Dr. X. Liu (18). pGEX-2T-p107 was a kind gift from Dr. Huang (19). pGEX-2T-pRB (1–928), pGEX-2T-p107 deletion constructs (252–1068), and spacer (385–949) were gifts from Dr. Livingston (20). pGEX-2T-p130 was a gift from Dr. DeCaprio (21). pCS2+MT-B55α full length and deletion mutants were gifts from Dr. C. Liu (21). pGEX-2T-p107 deletion constructs p107 (1–1068)1, p107 (254–1068), and p107 pocket (385–949) (pocket) were used as templates to generate additional deletion constructs using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) and the reverse and forward primers listed in supplemental Table 1. The N terminus of the p107 construct (N) was created by digesting pGEX-2T-p107 (1–1068) with DraIII and SmaI and releasing the pocket and C terminus. The construct lacking the N terminus (−N) was generated by digesting the mutant pGEX-2T-p107 (254–1068) and pGEX-2T-p107 pocket (385–949) with EcoRI and inserting the C terminus next to the pocket. Similarly, the mutant lacking the C terminus (−C) was generated by digesting pGEX-2T-p107 (1–1068) and pGEX-2T-p107 pocket (385–949) with DraIII and SmaI and inserting the pocket into the N terminus. Partial B and C terminus (pBC) was created by digesting full-length pGEX-2T-p107 (1–1068) with EcoRI and religating after removing the fragment. Constructs containing the spacer (S) and B and C domain (SBC) and pocket domains were further used along with the above primers to generate SC, AS, and spacer domains. All constructs were further verified by sequencing. FLAG-tagged p107, p130, and pRB. Expression vectors were generated by PCR amplification using pGEX-2T-p107, -p130, and -pRB as templates and the primers listed in supplemental Table 2, which contain BamHI or NotI restriction enzyme sites. pCEP-4HA-B56α, -B56β, -B56γ1, and -B56γ3, were generous gifts from Dr. Virshup (22). The three-HA cassette was released by NotI digestion to generate single HA (pCEP-1HA) derivatives of these constructs. HA-PR70, HA-B55δ, HA-PR48, and HA-PR72 mammalian expression constructs were generated by PCR amplification of pCMV-SPORT-6.1-PR70 (ATCC number 9579873), pcDNA/TO-FLAG-B55δ (a gift from Dr. Wadzinski), pTarget-PR48 (a gift from Dr. Williams), and pRC/CMV-HAPR72 (gift from Dr. Bernards) using primers with restriction site extensions (NotI, XhoI, or BamHI) listed in supplemental Table 3. The amplified products were subcloned in pCEP-1-HA vector and verified by sequencing. B55α point mutants were generated utilizing pCS2+MT-B55α as a template via QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) using primers listed in supplemental Table 4. All constructs were verified by sequencing.

Transient Transfections and Viral Transductions

Transfections were performed using the FuGENE 6 reagent (Roche Applied Science) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection. Recombinant adenoviruses encoding SV40 small t antigen (Ad-st) and enhanced GFP were obtained from B. Thimmapaya and P. Ruiz, respectively, and amplified as described previously in Ref. 6. U-2 OS cells were transduced at a multiplicity of infection of 50 pfu/cell. Cells were harvested 24 h after transduction for analysis.

shRNA Cell Lines

shRNA cell lines were generated by co-transfecting plasmids encoding specific shRNAs with a pBABE puromycin-selectable plasmid at a 1:10 ratio followed by selection in medium containing puromycin (2 μg/ml) for 72 h. pSUPER-B55α and PR48 shRNA constructs were a gift from Dr. Bernards: B55α-PPP2R2A (5′-CAGGAGATAAAGGTGGTAG-3′, 5′-GACCAGAAGGGTATAACTT-3′, and 5′-CATATTTATCTGCAGATGA-3′) and PR48-PPP2R3B (5′-CACGCACCCGGGGCTGTCG-3′ and 5′-CGTCTTCTTCGACACCTTC-3′). Empty pSUPER constructs were used as a negative control. The following retroviral constructs were obtained from Open Biosystems: B55α-PPP2R2A (V2HS_78650); PR48-PPP2R3B (V2HS_71705), and B56α-PPP2R5A (V2HS_57967).

Myc-B55α WT, D197K, and Control Empty Vector Cell Lines

Myc-B55α WT, D197K, and empty vector cell lines were generated via retroviral transduction of U-2 OS cells with constructs containing Myc-tagged B55α WT or D197K cloned from pCS2+MT-B55α into pMSCV-puromycin (Clontech). 293T cells were transfected with equal amounts of the corresponding pMSCV-puromycin vectors and pCL-Ampho (Imgenex) packaging construct DNA using the calcium phosphate method. Supernatants were collected 48 h after transfection and added to the target cells. Medium containing 1 μg/ml puromycin was added 24 h after infection.

RESULTS

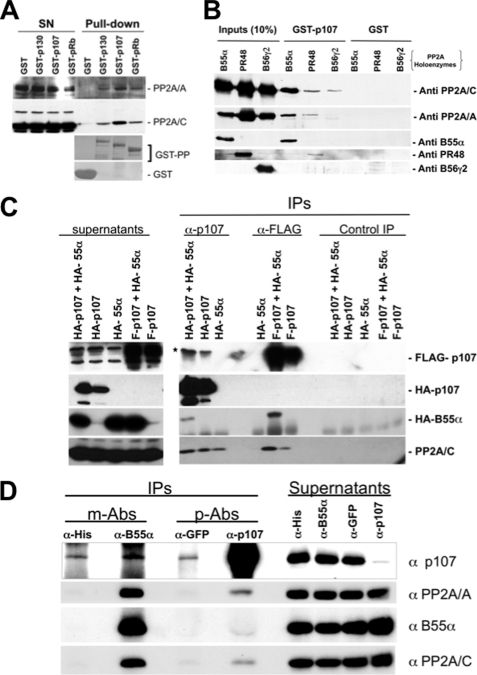

We have previously proposed that PP2A plays a direct role in restricting the phosphorylation of pocket proteins through the cell cycle (6). Although we have detected endogenous interactions between p130 and p107 with the catalytic subunit of PP2A and implicated an SV40 st-sensitive holoenzyme in counteracting CDK-mediated phosphorylation of pocket proteins, the nature of the PP2A/B subunit(s) is not known. To determine whether affinity-purified pocket proteins form complexes with subunits of the PP2A holoenzyme, we first determined whether recombinant GST-tagged pocket proteins pull down PP2A/A and PP2A/C from lysates of human cells. Comparable amounts of full-length GST-p130, GST-p107, GST-pRB, or an excess amount of GST loaded on glutathione beads were incubated with whole cell lysates of exponentially growing U-2 OS cells and extensively washed. Complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and specific biding of endogenous PP2A/A and PP2A/C was determined by Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. Fig. 1A shows that GST-p107 pulls significantly more PP2A/A and PP2A/C than p130 or pRB. This effect was independent of the batch of GST fusion preparation (data not shown). We next determined whether this binding was dose-dependent using increasing amounts of GST-p107 or an excess of control GST loaded onto glutathione beads (supplemental Fig. 1A). Of note, concentrations of GST-p107 that were not detectable by Coomassie Blue staining were sufficient for robust binding to PP2A/A and PP2A/C subunits, but we did not observe any binding of PP2A subunits to GST beads even when the amount of GST loaded was more that 2 orders of magnitude higher than the amount of GST-p107. We also determined whether this interaction could occur in lysates of human T98G cells that had been serum-starved and restimulated with serum for different periods of time. Supplemental Fig. 1B shows that bacterially expressed GST-p107 that is unphosphorylated can effectively form complexes with PP2A subunits present in the lysates of quiescent cells, as well as cells enriched at different points of the cell cycle. This finding is in agreement with our previous observation that endogenous PP2A/C interacts with p107/p130 through the cell cycle (6).

FIGURE 1.

p107 preferentially interacts with human trimeric PP2A complexes assembled with B55α and to a lesser extent PR48 (truncated form of PR70) in vitro and in cells. A, GST-pocket proteins pull down PP2A complexes from whole cell lysates of exponentially growing U-2 OS cells. 300 μg of whole cell lysate were incubated with comparable amounts of affinity-purified fusion GST-pocket proteins or an excess of GST protein loaded with glutathione beads. Supernatants (SN) and bound proteins (Pull-down) were resolved via SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot with antibodies specific for the proteins indicated. GST protein levels were detected via Coomassie Blue staining. B, PP2A/A and PP2A/C were coexpressed with a member of each B subunit family (B55α, B56γ2, and PR48) in insect cells and trimeric complexes purified as described previously (16). Comparable amounts of the three trimeric complexes normalized by the amount of PP2A/C in the complex were incubated with glutathione beads loaded with GST-p107 or GST and thoroughly washed. Complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected by Western blot analysis. C, B55α and p107 interact in U-2 OS cells. HA-p107 or FLAG-p107 (F-p107) were cotransfected with HA-B55α in U-2 OS cells. Complexes were immunoprecipitated with α-p107, α-FLAG, or control antibodies. Complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were detected with specific antibodies. The star marks two HA-p107 bands detected with α-p107 antibodies that were resistant to blotting membrane stripping previous to the α-FLAG blot. Relevant proteins are indicated. IPs, immunoprecipitations. D, low levels of endogenous B55α and p107 are detected in U-2 OS cells. Complexes were immunoprecipitated with α-p107, α-B55α, or control antibodies after overnight preclearing of cell lysates (1 mg) with control antibodies. Complexes were resolved via SDS-PAGE, and proteins were detected with α-p107, α-B55α, α-PP2A/A, and α-PP2A/C antibodies. m-Abs and p-Abs indicate monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies, respectively.

As the binding of GST-p107 with both PP2A/A and PP2A/C suggested that p107 was capturing PP2A holoenzymes, we set out to determine whether p107 had a preference for holoenzymes with particular B subunits. We arbitrarily selected B55α, B56γ, and PR48, which are members of the B, B′, and B″ families, respectively. The subunits of trimeric complexes that differed in their B subunit were coexpressed in insect cells. Affinity purification was performed with nickel columns, which bound His-tagged PP2A/A. The eluted complexes were further purified as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Trimeric complexes were normalized by the amount of PP2A/C as we observed an excess of free His-tagged PP2A in some preparations (Fig. 1B). GST pulldown assays were performed, and complex formation was monitored by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis. Fig. 1B shows that trimeric complexes containing the B55α subunit were preferentially pulled down by GST-p107. The amount of both PP2A/C and PP2A/A was much higher that the amount pulled down by complexes containing either PR48 or B56γ2. Additionally, the relative amount of B subunit pulled down from each complex as compared with the inputs was dramatically different. Considering the inputs, GST-p107 captured close to 10% of the B55α trimeric complex. However, under the same conditions, the amount of PR48 trimeric complex captured was much lower, and B56γ2 was undetectable. Thus, the selectivity of p107 for the B subunit correlates with the amounts of PP2A/A and PP2A/C pulled down, suggesting that the B subunit is the determinant mediating PP2A binding to p107 and that B55α is the preferred B subunit. To determine whether this in vitro selectivity could be recapitulated in cells, we transfected U-2 OS cells with the tagged constructs indicated in Fig. 1C and performed immunoprecipitations from whole cell lysates followed by Western blot analysis. As expected, anti-FLAG antibodies immunoprecipitated p107. HA-B55α was co-precipitated only when FLAG-p107 was coexpressed. Similarly, anti-p107 antibodies immunoprecipitated HA-p107, but HA-B55α was co-immunoprecipitated only when co-expressed with HA-p107. Endogenous PP2A/C was co-precipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies in amounts correlating with FLAG-p107 expression. Anti-p107 antibodies co-immunoprecipitated PP2A in the absence of HA-p107 overexpression because endogenous p107 co-immunoprecipitates with PP2A. We also determined whether endogenous p107-B55α complexes could be detected in U-2 OS cells. Anti-p107 antibodies efficiently co-immunoprecipitated PP2A/A and PP2A/C, whereas B55α was co-precipitated to a lower extent. B55α antibodies, which could not preclear B55α from the lysates, immunoprecipitated low levels of p107 that were above background detection (Fig. 1D). These data indicate low abundance of endogenous complexes, which may be due to the instability of the enzyme-substrate interaction. Therefore, B55α mediates an interaction between p107 and PP2A both in vitro and in cells.

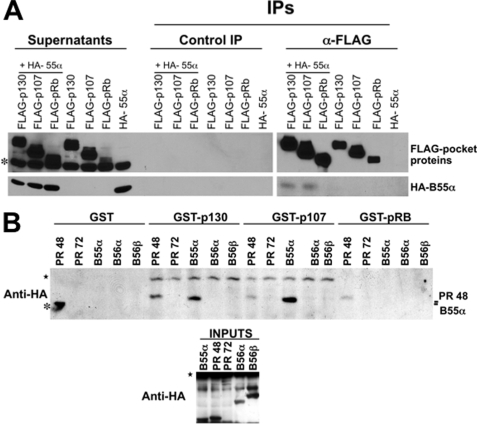

Next we determined whether other pocket proteins also interact with B55α under similar conditions. Fig. 2A shows that FLAG-p130 and FLAG-p107, but not FLAG-pRB, interact comparably with HA-B55α when pocket proteins are expressed with the same tag and at similar levels. A similar specificity was also noticed in in vitro pulldown assays using lysates of U-2 OS cells transfected with the HA-tagged B subunits indicated in Fig. 2B. GST-p107 preferentially associated with B55α and to a lesser extent with PR48, GST-p130 interacted with both B55α and PR48 at comparable levels, whereas GST-pRB associated with PR48 but not B55α. Altogether this suggests that pocket proteins are selectively targeted by distinct PP2A holoenzymes with B subunits belonging to at least two different families.

FIGURE 2.

Members of distinct B subunit family target particular pocket proteins. A, B55α interacts with p107 and p130 but not pRB in U-2 OS cells ectopically expressing tagged proteins. This analysis was carried out as in panel B. A cross-reacting band is indicated by an asterisk. IPs, immunoprecipitations. B, U-2 OS cells were transfected with HA-tagged subunits at comparable levels. Pulldown assays were performed with equivalent amounts of the indicated GST proteins. Bound B subunits and their input levels were detected via Western blot analysis. Cross-reacting bands are indicated by stars. The asterisk indicates a molecular mass marker co-run in the first well.

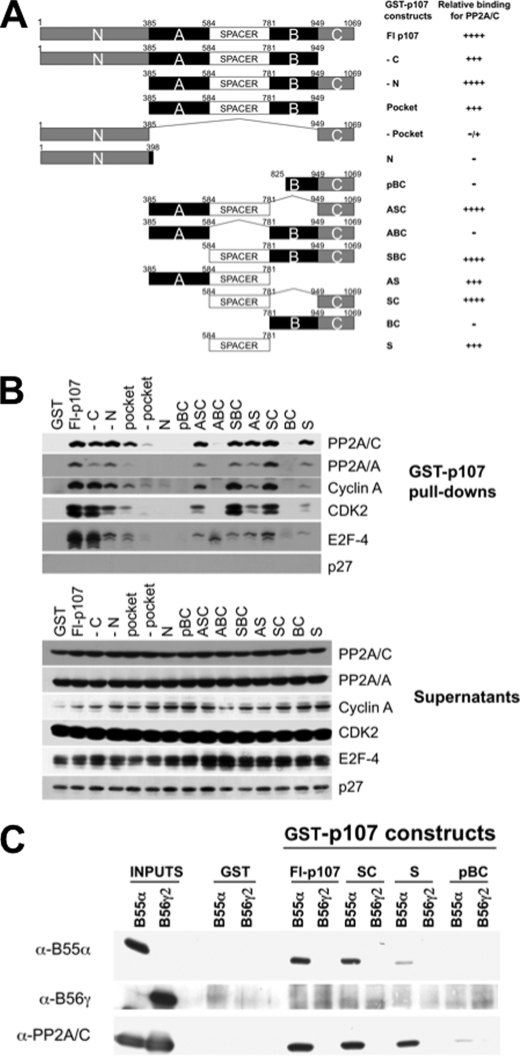

A preference for p107/p130 may have structural basis as there are regions in the pocket proteins that are more closely related in p107/p130 than in pRB, and these regions mediate pocket protein-specific interactions. Therefore, we utilized a series of p107 mutants to determine the domains in p107 that mediate the interaction with the PP2A holoenzyme. Deletion mutants that eliminate well defined domains on p107 were generated via PCR and are depicted in Fig. 3A. GST pulldown assays using these mutants revealed that the spacer region of p107 is essential for binding to PP2A/A and PP2A/C, as well the cyclin A-CDK2 complex, which is known to interact with the spacer region of p107/p130 (Fig. 3B). In contrast, E2F-4 could still form a complex in the absence of the spacer. In multiple experiments, we also observed that although the C terminus was not sufficient to form a complex with PP2A subunits, it enhanced the binding when connected to the spacer, and the absence of the C terminus in the context of an otherwise full-length protein reduced binding (Fig. 3B). This is even more obvious when the pulldown assays were performed using purified trimeric complexes. Fig. 3C shows that the spacer of p107 but not the C terminus domain interacts with B55α, but when the C terminus is fused to the spacer, the interaction of this deletion mutant is comparable with that of the full-length protein. As expected, no interactions were detected with B56γ2.

FIGURE 3.

The spacer region of p107 mediates the interaction with the PP2A-B55α complex, and the C terminus enhances the interaction. A, conserved p107 domains and summarized relative binding activity with PP2A (domain designations are defined under “Experimental Procedures”). B, the spacer domain of p107 is sufficient to interact with PP2A/A and PP2A/C, and the C terminus domain of p107 enhances this interaction but fails to interact with PP2A. Glutathione beads loaded with equivalent molar amounts of wild type and mutant GST-p107 fusion proteins or GST were incubated with lysates of exponentially growing U-2 OS cells. Complexes were analyzed by Western blot. C, purified PP2A-B55α but not PP2A-B56γ2 holoenzymes interact with the spacer of p107. Pulldown assays were performed with the indicated GST proteins and purified holoenzymes as in Fig. 2A.

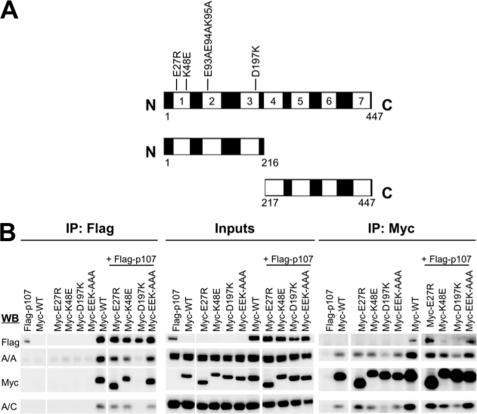

B55α consists of seven WD40 domains that form the blades of a β-propeller and a β-hairpin arm (Fig. 4A). p107 interacted both with the amino-terminal 1–216-amino acid fragment that contains the first three WD40 domains and the 217–447-amino acid C terminus fragment that contains the last four WD40 domains in cotransfection assays in U-2 OS cells (supplemental Fig. 2). However, these deletion forms of B55α poorly interacted with PP2A/C (Fig. 4A and supplemental Fig. 2) and PP2A/A (not shown). It has been recently reported that β-catenin, a substrate of B55α, also interacts with both domains (23). These results suggest that B55α substrates may make multiple contacts with the β-propeller structure. We also generated a series of point mutants targeting amino acids in the acidic top face of the β-propeller that have been previously found to be important for dephosphorylation of Tau by B55α (24). Fig. 4B shows that only residue Asp-197 was essential for binding to p107 in reciprocal immunoprecipitation assays from lysates of transfected cells with the indicated constructs. This residue was also clearly key for binding of B55α to PP2A/A and PP2A/C. Therefore, Asp-197 is critical for both formation of an holoenzyme and p107 recruitment. It also appeared that substitution of residue Lys-48 reduced binding to p107 despite efficient binding to PP2A/A and PP2A/C (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

B55α domains and residues required for binding to p107. A, structure of B55α and residues in its top acidic face that are important for dephosphorylation of the B55α substrate Tau. B, B55α Asp-197 is essential for the binding of p107. U-2 OS cells were co-transfected with FLAG-p107 and the indicated Myc-B55α constructs. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with α-FLAG and α-Myc antibodies and resolved via SDS-PAGE. Proteins were detected using α-FLAG, α-Myc, α-PP2A/A, and α-PP2A/C antibodies. IP, immunoprecipitates; WB, Western blots.

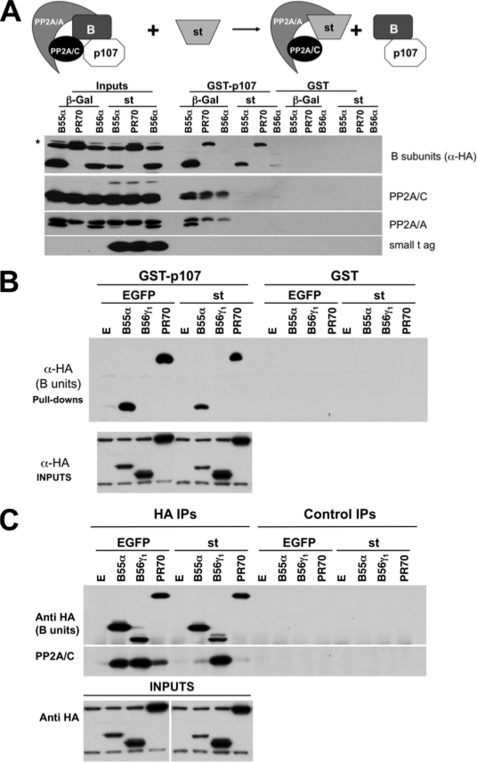

The preference of p107 for trimeric holoenzymes containing B55α and the binding of p107 to B55α deletion mutants that do not bind PP2A/C and PP2A/A strongly suggests that B55α mediates the interaction. As we have shown that expression of SV40 st in exponentially growing U-2 OS cells delays dephosphorylation of pocket proteins when CDK activity is compromised (6), it would be expected that st would prevent formation of trimeric PP2A complexes with p107. Therefore, U-2 OS cells were transfected with vectors encoding HA-tagged B55α, B56α, and PR70 subunits and subsequently transduced with recombinant adenoviruses expressing st or control β-galactosidase (Fig. 5A). Expression of st decreased the expression of B55α noticeably but not the expression of the other B subunits. GST-p107 specifically interacted with B55α and PR70 but not with B56α. Importantly, expression of st completely prevented the interaction of PP2A/A and PP2A/C with GST-p107 but not with the B subunits B55α and PR70. A similar experiment using cells transfected with HA-tagged B55α, B56γ1, and PR70 exhibited comparable results (Fig. 5B). Moreover, we did not detect an interaction between B56β and GST-p107 (data not shown). We next determined whether expression of st efficiently disrupted trimeric complexes by measuring dissociation of the PP2A/C subunit from HA-tagged B subunits in α-HA immunoprecipitates. Interestingly, st expression disrupted the interaction between PP2A/C and B55α or PR70 but not B56γ1 (Fig. 5C). Therefore, B55α and PR70 interact with p107 independently of the other subunits of the PP2A holoenzyme. Thus, disruption of B55α and/or PR70 PP2A holoenzymes by st could explain the effects of st in preventing dephosphorylation of pocket proteins when the activity of CDKs is compromised (6) (see below).

FIGURE 5.

B55α and PR70 mediate an st-sensitive interaction between the PP2A/C-PP2A/A dimer and p107. A and B, SV40 st antigen (small t ag) expression in U-2 OS cells prevents pulldown of PP2A subunits A and C, but not binding to select B subunits (B55α and PR70), by GST-p107. U-2 OS cells were transfected with vectors encoding HA-tagged B subunits (B55α, B56α, B56γ1, and PR70) and subsequently transduced with adenoviruses encoding st or β-galactosidase. GST pulldown assays were performed, and complexes were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis with antibodies raised against the indicated proteins. The effects of st on PP2A complexes are represented schematically. EGFP, enhanced GFP. C, lysates of cells described as in B were immunoprecipitated with α-HA antibodies, and the association of B subunits with PP2A/C in the presence or absence of st was determined via Western blot analysis. IP, immunoprecipitates.

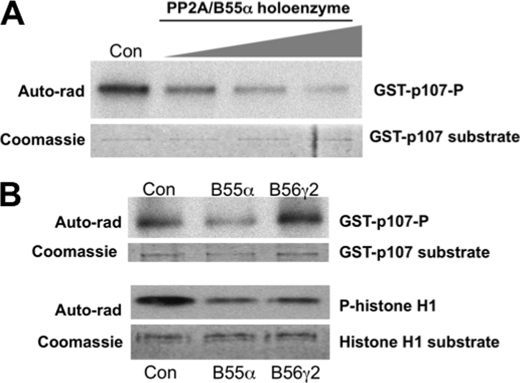

A stable interaction between the PP2A-B55α holoenzyme and p107 could facilitate and enzyme-substrate interaction if p107 is a bona fide substrate of this holoenzyme. Alternatively, p107 may be a modulator of PP2A function. To determine whether p107 is a specific substrate of the PP2A-B55α holoenzyme, p107 was phosphorylated in vitro with purified cyclin A-CDK2 complexes and [γ-32P]ATP and subsequently incubated with purified PP2A-B55α complexes in vitro. The reaction products were resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected by autoradiography. Fig. 6A shows dose-dependent dephosphorylation of CDK phosphorylated p107. To determine whether the observed dephosphorylation is specific, we sought to compare the activity of PP2A-B55α and PP2A-B56γ2 toward phosphorylated p107. To this end, we first determined the amount of holoenzyme required to obtain similar dephosphorylation of histone H1, a substrate that can be dephosphorylated by both holoenzymes (data not shown). Fig. 6B shows that at comparable levels, PP2A-B55α, but not B56γ2, dephosphorylates p107. In contrast, both holoenzymes dephosphorylate histone H1. These results show that the B subunit of the holoenzyme is critical for recognition of p107 as a substrate in vitro.

FIGURE 6.

Recombinant purified B55α trimeric PP2A complexes dephosphorylate phosphorylated p107 in vitro. A, increasing concentrations of purified PP2A-B55α complexes were incubated with GST-p107 previously phosphorylated (P) in vitro with purified cyclin A-CDK2 complexes. Con, control. Auto-rad, autoradiography. B, comparable amounts of PP2A-B55α and PP2A-B56γ2 purified holoenzymes were incubated with GST-p107 or histone H1 previously phosphorylated with cyclin A-CDK2 complexes.

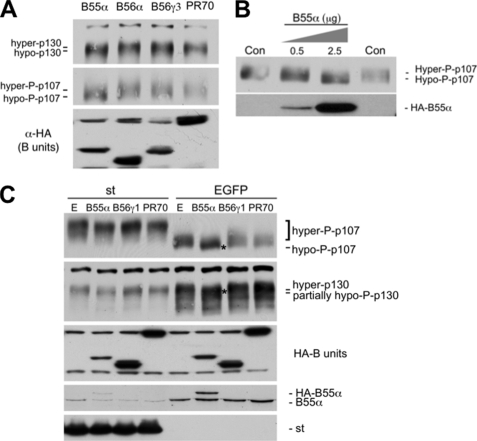

If p107 is a substrate of PP2A-B55α holoenzymes in vitro, modulation of its activity in cells could potentially affect the phosphorylation status of p107. To determine whether this is the case, we determined the comparative effects of ectopically expressing various HA-tagged B subunits. Fig. 7A shows that expression of B55α at levels comparable with other B subunits results in a shift in the phosphorylation status of p107, suggesting its dephosphorylation. A less pronounced shift is also observed for p130, which appears only partially dephosphorylated. No relative changes in mobility were noticed when the other B subunits were expressed. A dose-dependent increase in B55α expression shows a clearer shift on p107 migration (Fig. 7B). If ectopic expression of B55α induces p107/p130 dephosphorylation, the levels of B55α that target p107 in the cell must be limiting. We also rationalized that if st disrupts these complexes, B55α-induced dephosphorylation would be prevented. As expected, expression of B55α leads to a clear shift on p107 mobility, which was prevented by expression of st. Indeed, st expression leads to potent hyperphosphorylation of p107, suggesting that intact st-sensitive PP2A holoenzymes are required to maintain the phosphorylation state that is typical from proliferating cells. Noticeable, but less pronounced, dephosphorylation of p130 was observed, and st expression led to a decrease in the expression of p130, which could conceivably result from SCFSKP2-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of the unstable hyperphosphorylated forms of p130 (25, 26). Importantly, we measured the levels of endogenous and exogenous B55α using a specific antibody. This revealed that ectopic expression of B55α leads to an increase in total B55α expression that is less than double its levels in control mock-transfected cells. Altogether these data suggest that the levels of B55α in the cells are critical to maintain the phosphorylation state of p107.

FIGURE 7.

Ectopic expression of B55α, but not other subunits, results in st-sensitive dephosphorylation of p107 and p130. A, U-2 OS cells were transfected with the indicated B subunits at comparable levels, and their effect on the phosphorylation of endogenous p107 and p130 was determined via Western blot analysis. Hyper- and hypophosphorylated forms are indicated by hyper-P and hypo-P. B, dose-dependent increase in B55α expression leads to dose-dependent p107 dephosphorylation. U-2 OS cells were transfected as in A with the indicated amounts of plasmid encoding B55α. Dephosphorylation was assessed as in A. B55α expression was determined with α-HA antibodies. C, U-2 OS cells were transfected as in A and subsequently transduced with either st-expressing or enhanced GFP (EGFP)-expressing adenoviruses. Changes in phosphorylation status were assessed by Western blot analysis. Note that st expression leads to potent hyperphosphorylation of p107. Levels of B55α and st were determined with specific antibodies. Expression of B subunits was determined with α-HA antibodies. Hypophosphorylated p107 and partially hypophosphorylated p130 are marked by an asterisk.

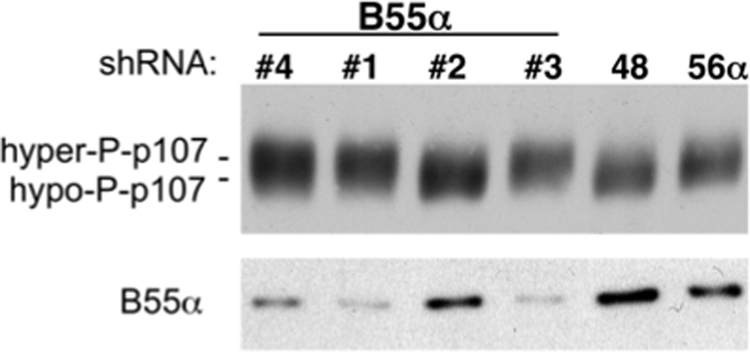

If the cellular levels of B55α are important to maintain the phosphorylation state of p107, specific knockdown of B55α should result in p107 hyperphosphorylation. U-2 OS cells were transfected with shRNA constructs targeting B55α. shRNA constructs targeting other B subunits were used as control. Fig. 8 shows that depletion of B55α correlated with the slower migration of p107. Maximum knockdown was obtained with shRNA 3, which also resulted in the most prominent shift followed by shRNA 1 and shRNA 4. Thus, the effects of st and B55α knockdown demonstrate that cellular B55α levels are important to restrict CDK-mediated hyperphosphorylation of p107.

FIGURE 8.

shRNA-mediated knockdown of B55α, but not other B subunits, results in hyperphosphorylation of p107. U-2 OS cells were transfected with the indicated shRNA constructs to B55α, B56α, and PR70. p107 phosphorylation status and B55α expression were assessed via Western blot analysis. Hyper- and hypophosphorylated forms are indicated by hyper-P and hypo-P.

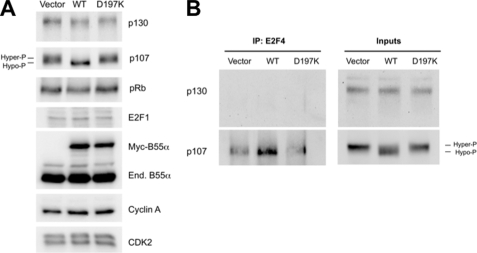

Because Asp-197 is essential for the B55α-p107 interaction, we next transduced U-2 OS cells with retroviruses encoding WT or D197K B55α. As expected, B55α, but not D197K, induced clear p107 dephosphorylation (Fig. 9A). These results further confirm that dephosphorylation of p107 is dependent on the p107-B55α interaction and/or the integrity of the holoenzyme. Interestingly, these cells proliferate despite prominent dephosphorylation of p107, indicating that selective dephosphorylation of p107 in U-2 OS cells is not sufficient for growth arrest. This likely occurs because p130 and pRB remain at least partially hyperphosphorylated and thus unable to cooperate in repressing E2F-depedent genes. Consistent with this idea, the levels of cyclin A, E2F-1, and p107, all E2F-depedent gene products, are not down-regulated with ectopic expression of B55α (Fig. 9A). Moreover, B55α-dependent dephosphorylation of p107 leads to formation of p107-E2F4 complexes, indicating that p107 is activated but unable to silence E2F-dependent gene expression in the absence of cooperating activation of p130 and pRB. In agreement with this idea, B55α expression did not accelerate cell cycle exit induced by contact inhibition in U-2 OS cells (supplemental Fig. 3).

FIGURE 9.

Ectopic expression of WT, but not a B55α-mutant defective in p107 binding, induces p107 activation. A, ectopic expression of WT, but not a p107-defective B55α-mutant, induces p107 dephosphorylation without altering the expression of E2F-dependent gene products. U-2 OS cells were transduced with retroviruses expressing B55α, B55αD197K, or no transgene and selected. Whole protein lysates were analyzed by Western blot with specific antibodies. Note that in this particular blot, p130 forms have not been resolved sufficiently to appreciate the relatively less marked dephosphorylation effects (Fig. 7, A and C). Hyper- and hypophosphorylated forms are indicated by Hyper-P and Hypo-P. B, 250 μg of whole protein lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-E2F4 antibodies, and complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis with antibodies to p107 and p130.

Altogether these results suggest that B55α is a key component of a regulatory buffer that restricts hyperphosphorylation of pocket proteins with a clear preference for p107. Nonetheless, distinct PP2A holoenzymes are required in addition to B55α to simultaneously reverse CDK action toward the three pocket proteins.

DISCUSSION

PP2A was previously implicated as the phosphatase that resets pocket proteins to an active state when the activity of CDKs is compromised (6). However, PP2A is a family of trimeric enzymes each containing one of many variable B subunits that confer substrate specificity and/or mediate subcellular localization. Therefore, the particular PP2A holoenzymes that target pocket proteins as part of the dynamic equilibrium with CDKs that determines the phosphorylation state of pocket proteins throughout the cell cycle are not known. Here we have identified a trimeric complex that contains the catalytic and scaffold subunits of PP2A and B55α, a member of the B family. This trimeric enzyme specifically associates with p107 and p130 in vitro and in cells. This interaction is direct and mediated by the B subunit, which targets the spacer region of p107. Our data show that the interaction with B55α is restricted to p107/p130 as pRB prefers PR70. Our results also show that the cellular levels of B55α are critical to maintain the levels of p107 phosphorylation that are seen in unperturbed cells; these results suggest that PP2A-B55α holoenzymes play an active role in determining the phosphorylation levels of p107 and its activation state rather than just catalyzing the dephosphorylation of p107, and to a lesser extent p130, when the activity of CDKs is compromised. Consistently with the requirement of activation of both p107 and p130 for growth arrest by CDK inhibitors (27), the selective activation of p107 by B55α is not sufficient to induce or accelerate growth arrest (Fig. 9 and supplemental Fig. 3). This highlights that, as is the case with CDKs, multiple PP2A holoenzymes are required to simultaneously activate pocket proteins.

Recent studies have implicated PP2A as a key regulator of pocket protein phosphorylation and function. The role of PP2A in controlling pocket protein function can be classified by two types of mechanisms, one that is constitutive in nature and one that is inducible. In terms of the former, PP2A keeps CDK-dependent and -independent phosphorylation of pocket proteins in check throughout the cell cycle and in quiescent cells (6). As for the latter mechanism, PP2A is induced in response to a variety of signals to activate pocket proteins (7–12). The B subunits that activate PP2A to target pocket proteins in response to a variety of signals are just beginning to be identified. Oxidative stress induced PR70, a B subunit from the B″ family, to associate with pRB catalyzing its dephosphorylation (7, 8). A recent study has shown that rapid dephosphorylation of p107 in response to FGFα signaling in a chondrosarcoma cell line is mediated by a PP2A complex containing a B subunit from either the B or the B′ family as dephosphorylation is sensitive to E4orf4, an adenoviral protein that inhibits these B subunits (12). However, the B subunits directing PP2A to pocket proteins in response to other signals remain to be identified.

We have previously proposed that PP2A resets phosphorylation of pocket proteins when the activity of CDKs is compromised (6). In this report, we show that limited overexpression of B55α results in marked dephosphorylation of p107, whereas B55α knockdown results in hyperphosphorylation. Dephosphorylation of p107 in cells ectopically expressing low levels of B55α is dependent on B55α being able to form a complex with p107. These data show that the PP2A-B55α holoenzyme is present in cells at levels that restrict hyperphosphorylation of pocket proteins. Indeed, transduction of U-2 OS cells with st results in hyperphosphorylation of p107 to levels beyond those observed in exponentially growing cells (Fig. 7C) or at any point of the cell cycle (data not shown). Therefore, either st is a more potent inhibitor of PP2A-B55α holoenzymes than the shRNAs targeting B55α or st targets other PP2A holoenzymes in addition to PP2A-B55α complexes that cooperate to restrict pocket protein phosphorylation. Likely candidates are PP2A-PR70 complexes as we have shown that they are also sensitive to st expression. Thus, it is conceivable that basal levels of PP2A-B55α and PP2A-PR70 complexes act coordinately to challenge CDK-mediated phosphorylation of pocket proteins in the absence of signal-specific stimuli that can lead to activation of particular PP2A complexes including PP2A-PR70.

The participation of PP2A complexes in addition to PP2A-B55α in maintaining an equilibrium with CDKs is obvious from our previous and current data as compromising CDK function results in coordinated dephosphorylation of the three pocket proteins (6), but PP2A-B55α complexes prefer p107 and p130 over pRB (Fig. 2A). As we have found that B55α directly associates with the spacer region of p107 that is conserved on p130, but more divergent in pRB, there is a structural basis for the selectivity of these interactions. In contrast, PR70 stably interacts with both the C terminus and the pocket of pRB (8), indicating a different mechanism of interaction that may facilitate association with the three pocket proteins albeit with clear different affinity. It remains to be elucidated whether both PP2A holoenzymes target different CDK sites or whether they exhibit specificity for distinct subsets of sites. The importance of a phosphatase other than PP1 in the activation of pocket proteins has been demonstrated genetically in Drosophila, where PP1 is not required for inhibition of E2f1 and the expression of E2f1-dependent genes in tissues where pRB is required, indicating that another phosphatase alone or redundantly with PP1 is responsible for pRB activation (28).

Another interesting observation made here is the effects of st in the phosphorylation of p107 and p130 in exponentially growing cells. The shift in p107 migration induced by st is very dramatic as it leads to complete disappearance of active p107 forms, which are responsible for restricting E2F-dependent transcription. A decrease in p130 expression is also clear, which may result from increased phosphorylation of the CDK sites that mediate p130 ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome (25, 26). Thus, it is conceivable that the effects of st on pocket protein phosphorylation enhance inactivation of pocket proteins, contributing to stimulation of cell proliferation by st. However, the effects of st in exponentially growing cells, which exhibit CDK activity, are in contrast with the effects of st in quiescent cells, where st does not seem to affect the phosphorylation of pocket proteins, likely as a result of the absence of CDK activity (29). Moreover, given the sensitivity of p107 phosphorylation to the levels of B55α, future analyses should ascertain whether abnormal hyperphosphorylation of pocket proteins is linked to deregulation of B55α and/or other B subunits that direct PP2A to pocket proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank many colleagues who have provided reagents as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant CA095569 (to X. G., J. G., and D. S. H.) and a National Institutes of Health Career Development Award (K02 AI01823) (to X. G.). This work was also supported by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Health (to X. G.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables 1–4 and Figs. 1–3.

- CDK

- cyclin-dependent kinase

- pRB

- retinoblastoma protein

- st

- small t antigen.

REFERENCES

- 1.Graña X., Garriga J., Mayol X. (1998) Oncogene 17, 3365–3383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sotillo E., Graña X. (2010) in Cell Cycle Deregulation in Cancer (Enders G. ed) pp. 3–22, Springer Publishing, New York [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graña X. (2008) Cancer Biol. Ther. 7, 842–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowland B. D., Bernards R. (2006) Cell 127, 871–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamrakar S., Rubin E., Ludlow J. W. (2000) Front Biosci. 5, D121–D137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garriga J., Jayaraman A. L., Limón A., Jayadeva G., Sotillo E., Truongcao M., Patsialou A., Wadzinski B. E., Graña X. (2004) Cell Cycle 3, 1320–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cicchillitti L., Fasanaro P., Biglioli P., Capogrossi M. C., Martelli F. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 19509–19517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magenta A., Fasanaro P., Romani S., Di Stefano V., Capogrossi M. C., Martelli F. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 873–882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avni D., Yang H., Martelli F., Hofmann F., ElShamy W. M., Ganesan S., Scully R., Livingston D. M. (2003) Mol. Cell 12, 735–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vuocolo S., Purev E., Zhang D., Bartek J., Hansen K., Soprano D. R., Soprano K. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41881–41889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voorhoeve P. M., Watson R. J., Farlie P. G., Bernards R., Lam E. W. (1999) Oncogene 18, 679–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolupaeva V., Laplantine E., Basilico C. (2008) PLoS One 3, e3447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Virshup D. M., Shenolikar S. (2009) Mol. Cell 33, 537–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goudreault M., D'Ambrosio L. M., Kean M. J., Mullin M. J., Larsen B. G., Sanchez A., Chaudhry S., Chen G. I., Sicheri F., Nesvizhskii A. I., Aebersold R., Raught B., Gingras A. C. (2009) Mol. Cell Proteomics 8, 157–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayol X., Garriga J., Graña X. (1995) Oncogene 11, 801–808 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan Z., Fedorov S. A., Mumby M. C., Williams R. S. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 1021–1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voorhoeve P. M., Hijmans E. M., Bernards R. (1999) Oncogene 18, 515–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H. H., Cai X., Shouse G. P., Piluso L. G., Liu X. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 402–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Z., Huong S. M., Wang X., Huang D. Y., Huang E. S. (2003) J. Virol. 77, 12660–12670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ewen M. E., Faha B., Harlow E., Livingston D. M. (1992) Science 255, 85–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Litovchick L., Chestukhin A., DeCaprio J. A. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 8970–8980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCright B., Rivers A. M., Audlin S., Virshup D. M. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 22081–22089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang W., Yang J., Liu Y., Chen X., Yu T., Jia J., Liu C. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 22649–22656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu Y., Chen Y., Zhang P., Jeffrey P. D., Shi Y. (2008) Mol. Cell 31, 873–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tedesco D., Lukas J., Reed S. I. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 2946–2957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhattacharya S., Garriga J., Calbó J., Yong T., Haines D. S., Graña X. (2003) Oncogene 22, 2443–2451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruce J. L., Hurford R. K., Jr., Classon M., Koh J., Dyson N. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 737–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swanhart L. M., Sanders A. N., Duronio R. J. (2007) Dev. Dyn. 236, 2567–2577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sotillo E., Garriga J., Kurimchak A., Graña X. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 11280–11292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.