Abstract

The phenotypic stability of somatic cells is essential for the maintenance of both structural and functional organ integrity of the adult human body. Deregulated cell plasticity could result in the development of debilitating diseases such as cancer, fibrosis, atherosclerosis, obesity, and type 2 diabetes. We have previously demonstrated that a nonsense mutation in the NPC2 gene, which encodes ubiquitous, highly conserved, secretory protein with unknown function, leads to activation of human skin fibroblasts. The activated fibroblasts, also known as myofibroblasts, have the properties of mesenchymal stem cells and are able to differentiate along the mesodermal and endodermal lineages. Here we show that NPC2-null, but not the normal skin fibroblasts, possess characteristics of adipogenic progenitors as demonstrated by their specific gene expression pattern as well as the ability for efficient differentiation into white adipocytes. The presence of NPC2 in mature white adipocytes was also necessary for their maintenance because silencing NPC2 in differentiated cells by siRNA stimulated PPARG expression, which was followed by a shift toward a more favorable, brown adipocyte-like metabolic state characterized by up-regulated lipolysis and increased insulin sensitivity. It appears that NPC2 controls both the adipogenesis and the metabolic state of mature white adipocytes through a common mechanism that is linked to activation of FGFR2 that could be followed by induction of PPARG expression. Altogether, the current study highlights NPC2 as a novel intracrine/autocrine factor that controls adipocyte differentiation and function as well as potential therapeutic target for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and related metabolic disorders.

Keywords: Adipocyte, Cell Differentiation, Cellular Regulation, Fibroblast, Signal Transduction

Introduction

We have reported in our previous communication that the loss of NPC2 protein in human dermal fibroblasts led to their activation.2 Given that activated fibroblasts, also known as myofibroblasts, have a phenotype similar to that of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC)3 as demonstrated by their ability to differentiate along the mesodermal and endodermal lineages (2, 3), we set to explore the NPC2-null fibroblast plasticity by probing their differentiation into adipocytes (mesoderm). It should be noted that although freshly isolated skin fibroblasts have a capacity for mesodermal differentiation (4, 5), they cannot maintain it for more than three passages (4), and as a result, continuously cultured skin fibroblasts are completely devoid of MSC-like properties (6). Activated fibroblasts, on the other hand, are self-sufficient and retain their ability for multi-lineage differentiation even after prolonged cell culture cycles (7, 8). Therefore, these cells could be considered as an important renewable source of autologous progenitors for tissue repair/regeneration.

The decision to focus on the adipogenic potential of NPC2-null fibroblasts was based on the following reasons. First, those cells displayed persistent basal activation of ERK1/2, MAPK, and NF-κB (1), which are known determinants of MSC commitment to adipogenic lineage (9, 10). Second, our DNA microarray screen of NPC2-null human skin fibroblasts revealed significantly up-regulated expression of several additional factors that drive MSC adipogenic differentiation, including master regulator of adipocyte differentiation PPARG (11), TCF21 (12), CREB5 (13), and BMP2 (14). Such apparent transformation of mature skin fibroblasts into adipocyte progenitor-like cells in the setting of NPC2 deficiency had raised a very important question: is the unperturbed function of NPC2 protein necessary for the maintenance of differentiated human adipocytes? The importance of the latter is underscored by a proposed causative link between impaired adipocyte function and development of metabolic syndrome (15). Metabolic syndrome is defined as a cohort of distinctive disorders including obesity, diabetes, and hypertension that underlie atherogenesis independently of hypercholesterolemia (16). Both adipocyte hypertrophy and atrophy, which are respectively linked to obesity and lipodystrophy, were shown to trigger and/or mediate metabolic syndrome (17–19).

In the current study we report that NPC2 protein may have a major role in the maintenance of the identity of somatic cells by restricting their conversion into other lineages. This novel and very important NPC2 function was highlighted by the observed strong commitment of NPC2-null human skin fibroblasts to adipogenic differentiation, which was clearly absent in the normal cells. The above notion was reinforced further by a demonstration that silencing the NPC2 gene by siRNA induces significant phenotypic alterations in mature human adipocytes. These alterations include up-regulated lipolysis, differential expression of genes involved in fatty acid transport and oxidation, suppression of lipogenic program, and increased insulin sensitivity. All of these phenotypic modifications were indicative of the acquired metabolically favorable state by NPC2-deficient adipocytes (20, 21) and were consistent with the observed persistent activation of several receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)/growth factor receptors, particularly that of FGFR2. The latter is known to be activated by and mediate the insulin-sensitizing effect of FGF21, a new promising therapeutic agent for the treatment of type II diabetes (22, 23).

In summary, the current study highlights NPC2 as a novel autocrine/paracrine factor responsible for the maintenance of somatic cell identity. However, the reported novel role for NPC2 in the regulation of adipocyte differentiation and function identifies this protein as a new target for pharmacologic intervention in the treatment of obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

DMEM, FBS, glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin were obtained from Cellgro. Adipocyte differentiation medium DM-2 was purchased from Zen-Bio.

Cell Lines

Normal human skin fibroblasts (CRL-1474) were obtained from ATCC. NPC2-null human skin fibroblasts were described elsewhere (24, 25). Terminally differentiated adipocytes were supplied by Zen-Bio. These cells were derived from subcutaneous primary human preadipocytes isolated from healthy individuals with body mass index levels of ≤25. 3T3-L1 mouse fibroblasts (American Tissue Culture Collection) were plated onto 96-well plates and differentiated into adipocytes as described (26).

DNA Microarray Assay

Total RNA was isolated from the normal and NPC2-null subconfluent (∼90%) cells that were cultured under the normal conditions (24, 25) by using Qiagen RNAeasy kit following the manufacturer's instructions. The samples were hybridized to the human U133A microarray (Affimetrix) by the Alvin Siteman Cancer Center's Multiplexed Gene Analysis Core at Washington University in St. Louis. Signal intensity ratios of >2-fold (up-regulated) or <2-fold (down-regulated) in at least two trials were considered regulated. Expression of the genes that were undetectable in the wild type cells and were only present in NPC2-null fibroblasts was termed “induced.”

Real Time RT-PCR

Cell total RNA was quantitatively converted into single-stranded cDNA by using a high capacity cDNA archive kit (Applied Biosystems). The particular genes were detected using the respective TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) on the 7300 real time RT-PCR system from the same manufacturer by relative quantitation employing β-glucuronidase as the reference gene.

Adipogenic Differentiation of NPC2-null Fibroblasts

Cells were seeded into 6-well culture plates and cultured as described (24, 25). Upon reaching confluence, normal fibroblast growth medium was changed to adipocyte differentiation medium DM-2 (Zen-Bio) containing dexamethasone, isobutylmethylxanthine, and PPARγ agonist. Over the course of differentiation (2 weeks), cell culture medium was refreshed every 4 days by replacing half of its volume in each well with the fresh one.

Adipogenic Differentiation of 3T3-L1 Preadipocytes

Adipogenic differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes was performed as described elsewhere (27).

NPC2 Gene Silencing by siRNA

The NPC2 gene expression was reduced in adipocytes by using siRNA. To that end, complimentary mRNA nucleotides derived from the human NPC2 sequence (Ambion, siRNA identification code 18116) were transfected into human primary adipocytes plated onto 96-well cell culture vessel (body mass index ≤ 25, obtained from Zen-Bio) using jetSI-ENDO (Polyplus Transfection) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The fluorescent derivative of the same transfection reagent, jetSI-ENDO-Fluo (Polyplus Transfection) was used in the parallel experiment to measure cell transfection efficiency. The extent of the gene silencing was assessed by real time RT-PCR as described below. The optimized transfection protocol demonstrated nearly 100% transfection efficiency and 71% reduction in NPC2 gene expression after 24 h. The NPC2 gene suppression after 48 h was at 63%. It should be noted that siRNA transfection caused no detectable effect on adipocyte viability. To evaluate potential adverse affects of the transfection reagent and siRNA introduction into the cells, the Silencer Negative Control 1 siRNA (Ambion) was used. The latter represents validated siRNA that does not target any known gene and, whenever tested in the current experiments, displayed no measurable effect.

Triacylglycerol (TAG) Measurement

The TAG content in differentiated human adipocytes was measured 24 h after transfection with NPC2 siRNA and compared with that of control using AdipoRed assay reagent from Cambrex. The AdipoRed fluorescence was registered on the Tecan GENios automated multimode microplate reader with the excitation set at 485 nm and the emission at 535 nm. The relative fluorescence intensity in the transfected wells was corrected for the background and cell number and normalized to that of control.

Lipolysis Measurement

Lipolysis was measured using an adipolysis assay kit (Chemicon) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To that end, 3T3-L1 mouse fibroblasts were plated onto 6-well plates and differentiated into adipocytes as described (26). Following differentiation, the cells were transfected with NPC2 siRNA as described above. Glycerol released into the medium during 24 h immediately after transfection, and nontransfected control was assayed against cell culture medium containing transfection reagent and quantified using glycerol as a standard by measuring absorption of the colored product at 540 nm on the Tecan GENios automated multi-mode microplate reader.

Glucose Uptake

Glucose uptake in NPC2-deficient human adipocytes was assessed by cell transfection with NPC2 siRNA that was followed by the measurement of 2-(N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino)-2-deoxyglucose, the fluorescent, nonhydrolyzable glucose analog (Molecular Probes) accumulation. 2-(N-(7-Nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino)-2-deoxyglucose incorporates into the cells through glucose transporters and truthfully mimics glucose uptake in specialized cells (28, 29).

Activation Status of the Membrane-bound RTK/Growth Factor Receptors (GFRs)

Activation status of the membrane-bound RTK/GFRs was probed with a human phosphoreceptor tyrosine kinase array kit from R & D Systems. The array is capable of simultaneously identifying the relative phosphorylation levels of 42 different RTKs. The sensitivity of the array is 2–20-fold higher as compared with the immunoprecipitation/Western blot analysis. To that end, wild type and NPC2-deficient adipocytes were cultured under normal conditions and lysed using BioVision nuclear/cytosol fractionation kit supplemented with 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin. Cytosolic fractions of the cell lysates (100 μg) isolated from normal human adipocytes and adipocytes 24 h after their transfection with NPC2 siRNA were simultaneously applied to and incubated with the array nitrocellulose membrane containing capture and control antibodies. After binding the extracellular domains of both phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated RTKs, unbound material was washed away. A pan phosphotyrosine antibody conjugated to HRP was used to detect phosphotyrosines on activated receptors by chemiluminescence. Signals from particular RTKs were identified according to the array map. Semiquantitative analysis of the respective signals was performed following the manufacturer's recommendation with the assistance of Adobe Photoshop CS4 Extended software.

MAPK Phosphorylation

MAPK phosphorylation was assessed using a human phospho-MAPK array kit from R & D Systems. This kit contained a nitrocellulose membrane with the capture and control antibodies against 21 MAPK, and their isoform was spotted in duplicate. Total cell lysates from normal and NPC2-deficient adipocytes were incubated with the membrane, unbound MAPK was washed away, and the mixture of phospho-site specific biotinylated antibodies was then applied to detect phosphorylated kinases using streptavidin-HRP and chemiluminescence. Semiquantitative analysis of the respective signals was performed following the manufacturer's recommendations with the assistance of Adobe Photoshop CS4 Extended software.

Reflected Light Differential Interference Contrast Imaging

Reflected light differential interference contrast imaging was carried out on the Leica DMIL microscope equipped with the EC3 digital camera and HI PLAN 10×/0.25, 20×/0.3, and 40×/0.5 objectives.

RESULTS

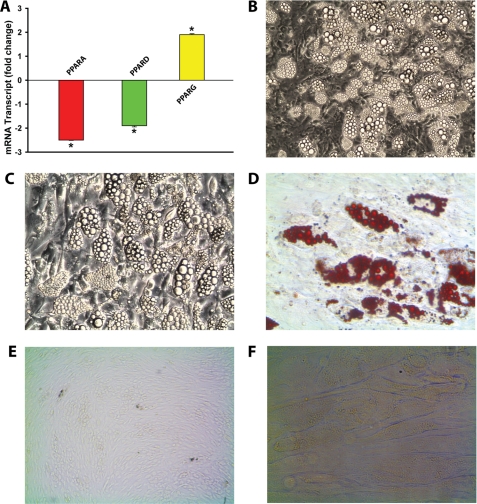

NPC2-null Human Skin Fibroblasts Display Propensity for Adipogenic Differentiation

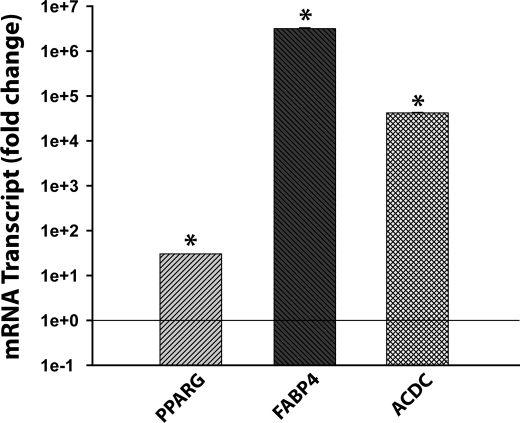

Our analysis of the gene expression pattern in NPC2-null human skin fibroblasts revealed an up-regulated, distinct set of genes that were known to positively regulate MSC commitment to adipogenic lineage (Table 1). Those genes included PPARG, the master regulator of adipocyte differentiation (11), as well as TCF21 (12), CREB5 (13), and BMP2 (14). We confirmed PPARG up-regulation (∼ 2-fold) by real time RT-PCR and also demonstrated its specificity when compared with the other PPAR isoforms, PPARA and PPARD, which displayed down-regulation by ∼2.5- and 2-fold, respectively (Fig. 1A). As expected, stimulation of NPC2-null fibroblasts with the adipogenic differentiation medium containing PPARγ agonist (see “Experimental Procedures”), induced a very strong and efficient differentiation of these cells into adipocytes (Fig. 1B). The latter was evidenced by the appearance of numerous large intracellular vesicles (Fig. 1C) that were positively stained with the lipid droplet-specific marker, Oil Red O (Fig. 1D). When similarly treated, no such effects were observed with normal human skin fibroblasts (Fig. 1, E and F). The adipogenic differentiation of NPC2-null fibroblasts was independently confirmed by a dramatic up-regulation of the specific marker gene expression such as PPARG (PPARγ, ∼30-fold), FABP4 (aP2, ∼3.2 × 106-fold), and ACDC (adiponectin, 4.2 × 104-fold) (Fig. 2). These PPARG and FABP4 values were within the range of that reported for mature human adipocytes differentiated from their progenitors in vitro (30). The relative increase in the ACDC mRNA level (4.2 × 104 ± 1378 (n = 3); Fig. 2) matched almost precisely that measured by us, 3.6 × 104 ± 302 (n = 3), when the mRNAs isolated from human adipogenic progenitors and differentiated adipocytes (Zen-Bio) were used. It should be noted that NPC2-null skin fibroblasts failed to differentiate along the osteogenic lineage when they were placed into human MSC osteogenic differentiation medium obtained from Lonza (data not shown). Altogether, the above data demonstrated clearly both the commitment and ability of NPC2-null skin fibroblasts to adipogenic differentiation in vitro.

TABLE 1.

Transcriptional signature of NPC2-null human fibroblasts as probed by DNA microarray; adipocyte differentiation factors

The term “Induced” identifies genes whose expression was undetectable in the wild type cells and were only present in NPC2-null fibroblasts. See text for experimental details.

| Probe set | Gene name | Symbol | Gene expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| 208510_s_at | Peroxisome proliferative-activated receptor gamma | PPARG | ↑2.3 |

| 204931_at | Transcription factor 21 | TCF21 | Induced |

| 205931_s_at | cAMP responsive element binding protein 5 | CREB5 | Induced |

| 205289_at | Bone morphogenetic protein 2 | BMP2 | Induced |

FIGURE 1.

Adipogenic differentiation of NPC2-null human skin fibroblasts. A, expression of PPAR isoforms as probed by real time RT-PCR. B, reflected light differential interference contrast image of NPC2-null fibroblasts cultured in DM-2 adipocyte differentiation medium for 2 weeks, magnification 10×. C, same as B, magnification 20×. D, Oil Red O staining, magnification 20×. E, normal human skin fibroblasts cultured in DM-2 adipocyte differentiation medium for 2 weeks, magnification 10×. F, same as E, magnification 20×. The data shown in A were normalized to their respective controls and shown as the means ± S.E. *, p ≤ 0.05 as compared with control (n = 3).

FIGURE 2.

Expression of white adipocyte differentiation markers in NPC2-null human skin fibroblasts following their 2-week incubation in adipogenic medium. Relative mRNA content was assessed by real time RT-PCR. The data were normalized to their respective controls and shown as the means ± S.E. *, p ≤ 0.05 as compared with control (n = 3). Note the y axis logarithmic scale.

NPC2 Expression Is Up-Regulated at the Terminal Stage of Adipocyte Differentiation

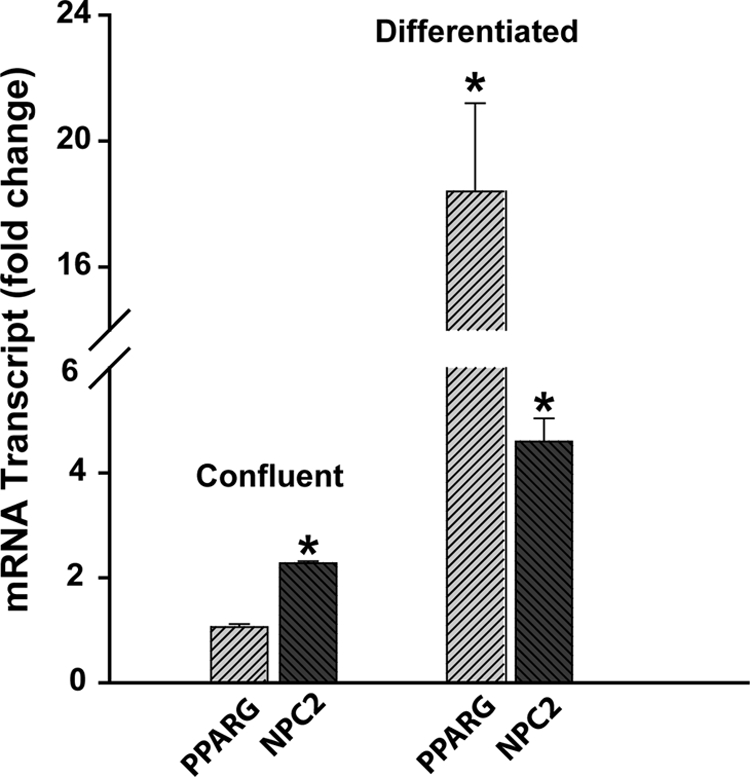

Additional and very important information regarding a putative role for NPC2 in regulation of adipocyte differentiation and function was obtained from the analysis of NPC2 gene expression at two distant stages of adipogenic differentiation: confluent, growth-arrested preadipocytes and terminally differentiated fat cells (Fig. 3). As in this figure, at the onset of differentiation, the level of NPC2 mRNA in the confluent 3T3-L1 preadipocytes was increased by more than 2-fold as compared with that of proliferating cells, whereas the respective PPARG mRNA level remained unchanged (Fig. 3). In terminally differentiated adipocytes, however, the NPC2 mRNA displayed ∼4.6-fold induction, which was accompanied by more than 18-fold stimulation of PPARG expression (Fig. 3). Based on this evidence, we concluded that NPC2 might have a dual role in adipocyte differentiation and function; on the one hand, it may serve as a gate keeper by precluding the lineage-committed preadipocytes from premature differentiation, and on the other hand, it could participate, along with PPARγ, in the maintenance of mature white adipocytes (31–34). The phenotype of the latter appears to be in the equilibrium between the dedifferentiated and brown adipocyte-like states that could be induced through PPARγ loss-of-function (31, 32) and gain-of-function (33, 34), respectively. The white adipocytes with the brown adipocyte-like properties have been recently termed “brite adipocytes” (35) and are characterized by the up-regulated lipolysis, increased insulin sensitivity, and fatty acid oxidation (33–35). Based on the specific induction of PPARG expression in NPC2-null human fibroblasts (1), we hypothesized that NPC2 deficiency in mature white adipocytes would result in the PPARG gain-of-function, which would cause a shift of phenotypic equilibrium toward brown-like adipocytes.

FIGURE 3.

NPC2 and PPARγ gene expression in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes during different stages of adipogenic differentiation. Relative mRNA content was assessed by real time RT-PCR. The data were normalized to their respective controls (proliferating cells, <50% confluency) and shown as the means ± S.E. *, p ≤ 0.05 as compared with control (n = 3).

Silencing NPC2 Gene Expression in Adipocytes Stimulates PPARG Expression, Lipolysis, and Insulin Sensitization

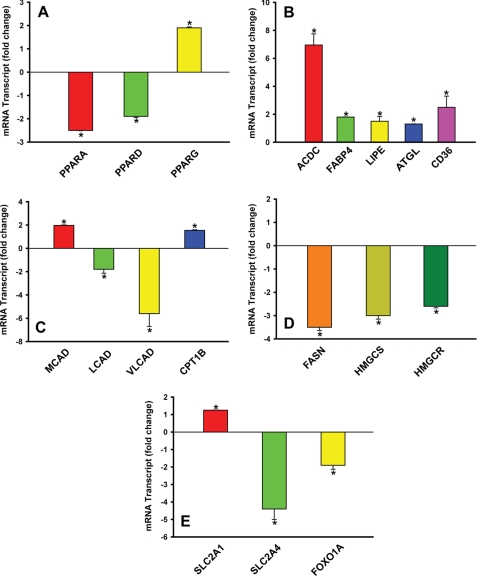

We tested the above hypothesis by silencing NPC2 expression in mature adipocytes through siRNA (Fig. 4). As is seen from this figure, NPC2 deficiency resulted in specific up-regulation of PPARG (∼2-fold) with the concomitant down-regulation of PPARA and PPARD (∼2-fold; Fig. 4A). This PPAR isoform expression pattern was almost identical to that of NPC2-null human skin fibroblasts (Fig. 1A) and thus could be indicative of the bona fide function of NPC2 as a regulator of PPAR-mediated transcriptional programs, yet the observed differential expression of PPAR isoforms in NPC2-deficient mature adipocytes (Fig. 4A) matched precisely their respective target gene expression pattern, which effectively ruled out adipocyte dedifferentiation (ACDC and FABP4, Fig. 4B; FOXO1A, Fig. 4E) and reflected significant genomic modifications in a number of metabolic programs consistent with the stimulated lipolysis (LIPE and ATGL; Fig. 4B), up-regulated fatty acid transport (CD36 and FABP4; Fig. 4B), and mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation (CPT1B; Fig. 4C) through a key β-oxidation enzyme, MCAD (36) (Fig. 4C), suppressed lipogenesis (Fig. 4D), as well as stimulated glucose transport (SLC2A1 and SLC2A4; Fig. 4E) and glucose oxidation (FOXO1A; Fig. 4E). It is noteworthy that FOXO1A, known to be a potent negative regulator of adipocyte differentiation (37) as well as a promoter of insulin resistance (38), was efficiently (∼2-fold) down-regulated in NPC2-deficient adipocytes (Fig. 4E).

FIGURE 4.

Real time RT-PCR screen of human mature adipocytes transfected with NPC2 siRNA. A, differential expression of PPAR isoforms. B–E, expression of specific genes that regulate lipolysis and transport of fatty acids (B), fatty acid oxidation (C), lipogenesis (D), and glucose transport (E). The data were normalized to their respective controls and shown as the means ± S.E. *, p ≤ 0.05 as compared with control (n = 3). Total RNA was collected 24 h after siRNA transfection.

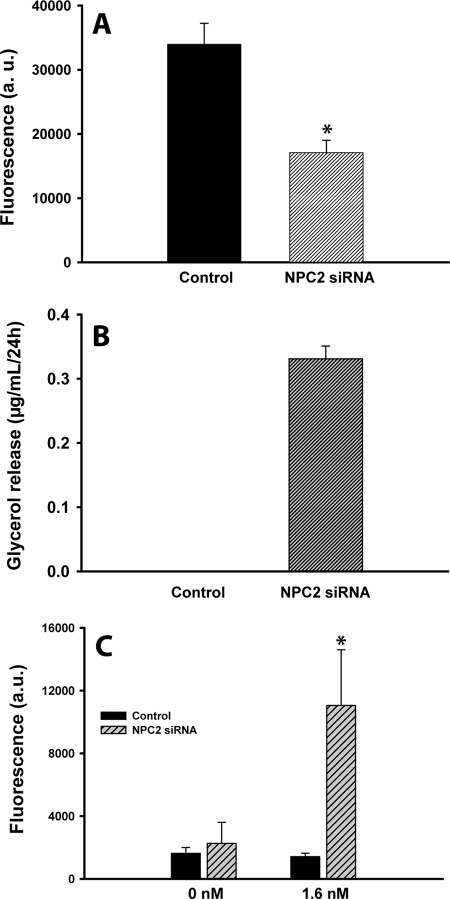

The elevated expression of LIPE (HSL) and ATGL in NPC2-deficient adipocytes (Fig. 4B) was indicative of their up-regulated lipolytic program. The latter was independently confirmed by measuring the adipocyte TAG level and glycerol release into the medium (Fig. 5). As is seen from this figure, the cells under study demonstrated ∼2-fold reduction in their TAG content (Fig. 5A), which was accompanied by glycerol appearance in conditioned medium (Fig. 5B). The latter identifies up-regulated lipolysis as a cause for the observed adipocyte delipidation.

FIGURE 5.

Metabolic shift in NPC2-deficent mature adipocytes. A, TAG depletion in human adipocytes following the NPC2 gene silencing by siRNA. TAG was measured using AdipoRed assay reagent. B, stimulated lipolysis in human adipocytes following the NPC2 gene silencing by siRNA. Lipolysis was probed by measuring glycerol release into the medium. C, basal and insulin-dependent glucose uptake in mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes after their transfection with NPC2 siRNA. All of the measurements were performed at 37 °C and 24 h after siRNA transfection. The results are the means ± S.E. *, p ≤ 0.05 as compared with nontransfected control (n = 3–7).

We next examined whether the observed up-regulation of PPARG would result in the stimulated, insulin-dependent glucose uptake. It should be noted that detected up-regulation of SLC2A1 (GLUT1, ∼1.3-fold) and down-regulation of SLC2A4 (GLUT4, ∼4.5-fold) (Fig. 4E) were consistent with the respective transcriptional regulatory effects of PPARγ (39–41) as well as with the mechanism of insulin-dependent glucose transport stimulated by PPARγ activation in mature adipocytes (40, 42). To that end, we probed both basal and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in differentiated adipocytes transfected with NPC2 siRNA (Fig. 5C). As is seen from this figure, suppression of NPC2 gene expression by 70% resulted in dramatic up-regulation of the insulin-dependent glucose uptake in the setting where the basal glucose uptake was unchanged.

NPC2 Deficiency Renders Activation of RTK/GFR Signaling

To identify a molecular mechanism responsible for the up-regulated expression of PPARγ and respective metabolic changes in NPC2-deficient adipocytes, we turned our attention to the RTK/GFR signaling, particularly that of FGFR. This decision was based on the following reasons. First, it was established that PPARG up-regulation at the onset of adipocyte differentiation was regulated through the FGF-dependent activation of MEK/ERK signaling (43). Second, the observed activation of lipolytic program and enhanced insulin sensitivity in NPC2-deficient mature adipocytes were consistent with the recently reported insulin-sensitizing effect of FGF21, which is considered to be a novel therapeutic agent for the treatment of type 2 diabetes (22, 23). Third, the FGF21 membrane receptor, FGFR2 (40), displayed constitutive activation in NPC2-null skin fibroblasts (1) along with the up-regulated expression of PPARG (Fig. 1A).

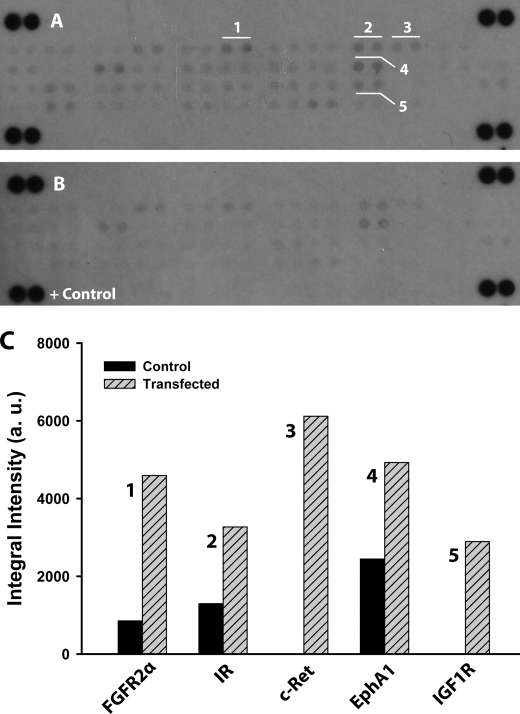

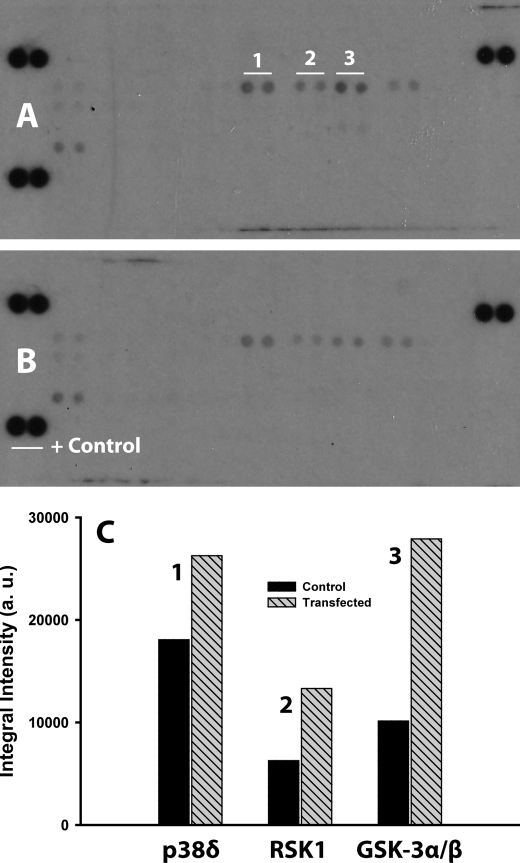

To that end, we probed the activation status of the membrane-bound and soluble RTK/GFR in unstimulated control and NPC2-deficient human adipocytes by differential display using human phospho-RTK array (see “Experimental Procedures”). The respective data are presented in the Fig. 6. As in this figure, several RTK/GFR demonstrated up-regulated activity, notably FGFR2α (FGFR2 IIIc), insulin receptor, and insulin-like growth factor-I receptor. All three of these receptors are well known mediators of the insulin action in adipocytes, and their activation status was independently confirmed by the stimulated phosphorylation of their downstream targets, p38δ, ribosomal S6 kinase 1, and glycogen synthase kinase 3α/β MAPKs (Fig. 7). Therefore, the above data may provide a molecular basis for the increased insulin sensitivity in NPC2-deficient mature adipocytes. In summary, the NPC2 protein could regulate both the adipogenic lineage commitment of human skin fibroblasts and the maintenance of mature adipocytes through a common mechanism that controls FGFR2 activation.

FIGURE 6.

Sustained RTK/GFR activation in NPC2-deficient human adipocytes. A and B, the RTK/GFR activation was probed by phospho-RTK antibody array using total cell lysates that were collected from mature human adipocytes 24 after their transfection with NPC2 siRNA (A) and nontransfected cells (B). Signals from particular RTK/GFR are shown in duplicate and numerically labeled as: FGFR2α (FGFR2 IIIc) (1); insulin receptor (IR) (2); c-Ret; 4-EphA1, and 5-insulin-like growth factor-I receptor (3). C, semiquantitative analysis of the duplicative signals shown in A and their respective counterparts in B. The images of A and B were inverted, and the intensities of particular GFR/RTKs were measured and corrected for the background using Adobe Photoshop CS4 Extended software. The data shown are the averages (n = 2).

FIGURE 7.

Analysis of MAPK activation in NPC2-deficient human adipocytes. The MAPK activation was probed by a human phospho-MAPK array kit. Cell lysates were collected from mature human adipocytes 24 h after their transfection with NPC2 siRNA as well as from nontransfected cells. The array membranes were simultaneously treated with the respective lysates and processed, and specific MAPKs were identified as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, membrane incubated with the lysate from siRNA transfected cells. Signals from particular MAPK are shown in duplicate and numerically labeled as: p38δ (MAPK13) (1); ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (MAPKAPK1α) (2), and glycogen synthase kinase (GSK) 3α/β (3). B, membrane incubated with the lysate from control cells. C, semiquantitative analysis of the duplicative signals shown in A. The data shown are averages (n = 2).

DISCUSSION

The proper function of the adult human body depends upon the integrity of its organs, which in turn relies heavily on the phenotypic stability of the specialized cells. Deregulated somatic cell plasticity could result in the aberrant cell differentiation, dedifferentiation, or trans-differentiation leading to the development of debilitating diseases such as cancer, fibrosis, atherosclerosis, obesity, and diabetes. The present report provides several important insights into the molecular mechanism underlying the regulation of somatic cell plasticity.

First, we have demonstrated that primary human skin fibroblasts bearing NPC2-null mutation possess characteristics of adipogenic lineage committed MSC. Such unique properties of NPC2-null fibroblasts were highlighted by the up-regulated expression of PPARG, the master regulator of adipogenesis (11), as well as several other genes linked to the adipogenic program, namely TCF21 (12), CREB5 (13), and BMP2 (14). In addition, these cells displayed constitutive activation of ERK1/2 MAPK and NF-κB (1), two other well known positive factors of adipogenic differentiation (9, 10). As a result, NPC2-null skin fibroblasts efficiently differentiated into mature adipocytes when they were placed into adipogenic medium but displayed no ability for osteogenic differentiation under the respective stimuli. Therefore, the loss of NPC2 protein in human skin fibroblasts produces a phenotype with a strong resemblance to adipogenically committed MSC. This discovery is of high importance, because despite our vast knowledge regarding the mechanisms of adipocyte differentiation from their progenitor cells, very little is known about the mechanism(s) regulating adipogenic lineage commitment (44).

Second, we report here that NPC2 not only regulates selection of adipogenic progenitor cells but is also responsible for the maintenance of mature adipocytes. The latter was demonstrated by a dramatic phenotypic shift of differentiated white adipocytes transfected with NPC2 siRNA toward brown-like adipocytes with the metabolically favorable profile that includes stimulated lipolysis and increased insulin sensitivity (33–35). This metabolic shift was associated with the significantly up-regulated expression of adipogenic markers, particularly that of adiponectin (ACDC, 7-fold), in mature adipocytes following their transfection with NPC2 siRNA. Importantly, a similar metabolic profile of white adipose tissue has been recently reported in mice with an elevated level of adiponectin (45).

Third, it appears that NPC2 controls both the adipocyte differentiation and maintenance through a common mechanism that is linked to selective PPARγ activation. Indeed, both the human skin fibroblasts bearing natural NPC2 nonsense mutation and terminally differentiated white adipocytes with the siRNA-silenced NPC2 gene are characterized by the same differential PPAR isoform expression pattern: significant PPARG up-regulation with the almost mirrored concomitant down-regulation of PPARA and PPARD. The mechanism for such differential PPAR expression in the setting of NPC2 deficiency is unknown but could be linked to the constitutive activation of FGFR2 observed in both NPC2-null skin fibroblasts (1) and NPC2-deficient mature adipocytes (current study). This receptor as well as its ligands, FGF-1 and FGF-2 (46), are known potent adipogenic stimuli (43, 47, 48) that trigger PPARG up-regulation through C/EBP induction (43). The latter, in turn, could also lead to suppression of PPARA and PPARD (49, 50). Given that FGFR2 activation in mature adipocytes is also responsible for their switch to a metabolically favorable state (33–35), one could place FGFR2 activation upstream of the respective differential expression of PPAR isoforms in both of the above processes.

In addition, it has been recently reported that FGFR2 serves as a receptor for FGF21 (40), the novel therapeutic agent for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and related metabolic disorders (22, 23). Intriguingly, both FGF21 and NPC2 are highly expressed in the liver, and their expression was regulated positively by PPARα (1, 51, 52). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that NPC2 might contribute to FGF → FGFR2 signaling by creating a negative feedback loop in response to PPARα activation by metabolic factors.

Altogether, the current study identifies NPC2 as a novel intracrine/autocrine factor that negatively regulates development of adipogenic progenitors and their subsequent differentiation into mature adipocytes. In addition, NPC2 may serve as an essential factor for the maintenance of differentiated white adipocytes by preventing their switch to a metabolically active state similar to that of brown adipocytes. Therefore, NPC2 may represent a novel target for the pharmacologic treatment of obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dan Ory (Washington University in St. Louis) for providing us with the NPC2-null human fibroblasts.

This work was supported by an American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant and the University of Cincinnati Millennium Fund and the Dept. of Internal Medicine Start-Up Fund (to A. F.).

C. Csepeggi, M. Jiang, F. Kojima, L. J. Crofford, and A. Frolov, manuscript submitted.

- MSC

- mesenchymal stem cells

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- GFR

- growth factor receptor

- RTK

- receptor tyrosine kinase

- FGFR

- FGF receptor

- TAG

- triacylglycerol.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chinetti-Gbaguidi G., Rigamonti E., Helin L., Mutka A. L., Lepore M., Fruchart J. C., Clavey V., Ikonen E., Lestavel S., Staels B. (2005) J. Lipid Res. 46, 2717–2725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sen M., Lauterbach K., El-Gabalawy H., Firestein G. S., Corr M., Carson D. A. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 2791–2796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li X., Makarov S. S. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 17432–17437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lysy P. A., Smets F., Sibille C., Najimi M., Sokal E. M. (2007) Hepatology 46, 1574–1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Junker J. P., Sommar P., Skog M., Johnson H., Kratz G. (2010) Cells Tissues Organs 191, 105–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pittenger M. F., Mackay A. M., Beck S. C., Jaiswal R. K., Douglas R., Mosca J. D., Moorman M. A., Simonetti D. W., Craig S., Marshak D. R. (1999) Science 284, 143–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamasaki S., Nakashima T., Kawakami A., Miyashita T., Ida H., Migita K., Nakata K., Eguchi K. (2002) Clin. Exp. Immunol. 129, 379–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamasaki S., Nakashima T., Kawakami A., Miyashita T., Tanaka F., Ida H., Migita K., Origuchi T., Eguchi K. (2004) Rheumatology 43, 448–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bost F., Aouadi M., Caron L., Binétruy B. (2005) Biochimie 87, 51–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berg A. H., Lin Y., Lisanti M. P., Scherer P. E. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 287, E1178–E1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen E. D., Spiegelman B. M. (2000) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 145–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Timmons J. A., Wennmalm K., Larsson O., Walden T. B., Lassmann T., Petrovic N., Hamilton D. L., Gimeno R. E., Wahlestedt C., Baar K., Nedergaard J., Cannon B. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 4401–4406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reusch J. E., Colton L. A., Klemm D. J. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 1008–1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang H., Song T. J., Li X., Hu L., He Q., Liu M., Lane M. D., Tang Q. Q. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12670–12675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laclaustra M., Corella D., Ordovas J. M. (2007) Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 17, 125–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuzawa Y. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580, 2917–2921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chehab F. F. (2008) Endocrinology 149, 925–934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berg A. H., Scherer P. E. (2005) Circ. Res. 96, 939–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maury E., Brichard S. M. (2010) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 314, 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burgermeister E., Schnoebelen A., Flament A., Benz J., Stihle M., Gsell B., Rufer A., Ruf A., Kuhn B., Märki H. P., Mizrahi J., Sebokova E., Niesor E., Meyer M. (2006) Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 809–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tuncman G., Erbay E., Hom X., De, Vivo I., Campos H., Rimm E. B., Hotamisligil G. S. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6970–6975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kharitonenkov A., Shanafelt A. B. (2008) BioDrugs. 22, 37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kliewer S. A., Mangelsdorf D. J. (2010) Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 91, 254S–257S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frolov A., Srivastava K., Daphna-Iken D., Traub L. M., Schaffer J. E., Ory D. S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 46414–46421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frolov A., Zielinski S. E., Crowley J. R., Dudley-Rucker N., Schaffer J. E., Ory D. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25517–25525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frost S. C., Lane M. D. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260, 2646–2652 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim Y. B., Uotani S., Pierroz D. D., Flier J. S., Kahn B. B. (2000) Endocrinology 141, 2328–2339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamada K., Nakata M., Horimoto N., Saito M., Matsuoka H., Inagaki N. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 22278–22283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamada K., Saito M., Matsuoka H., Inagaki N. (2007) Nat. Prot. 2, 753–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urs S., Smith C., Campbell B., Saxton A. M., Taylor J., Zhang B., Snoddy J., Jones Voy B., Moustaid-Moussa N. (2004) J. Nutr. 134, 762–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamori Y., Masugi J., Nishino N., Kasuga M. (2002) Diabetes 51, 2045–2055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schupp M., Cristancho A. G., Lefterova M. I., Hanniman E. A., Briggs E. R., Steger D. J., Qatanani M., Curtin J. C., Schug J., Ochsner S. A., McKenna N. J., Lazar M. A. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 9458–9464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammarstedt A., Sopasakis V. R., Gogg S., Jansson P. A., Smith U. (2005) Diabetologia 48, 96–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Festuccia W. T., Laplante M., Berthiaume M., Gélinas Y., Deshaies Y. (2006) Diabetologia 49, 2427–2436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrovic N., Walden T. B., Shabalina I. G., Timmons J. A., Cannon B., Nedergaard J. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 7153–7164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vega R. B., Kelly D. P. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 31693–31699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakae J., Kitamura T., Kitamura Y., Biggs W. H., 3rd, Arden K. C., Accili D. (2003) Dev. Cell 4, 119–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakae J., Biggs W. H., 3rd, Kitamura T., Cavenee W. K., Wright C. V., Arden K. C., Accili D. (2002) Nat. Genet. 32, 245–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tafuri S. R. (1996) Endocrinology 137, 4706–4712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moyers J. S., Shiyanova T. L., Mehrbod F., Dunbar J. D., Noblitt T. W., Otto K. A., Reifel-Miller A., Kharitonenkov A. (2007) J. Cell. Physiol. 210, 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Armoni M., Kritz N., Harel C., Bar-Yoseph F., Chen H., Quon M. J., Karnieli E. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 30614–30623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nugent C., Prins J. B., Whitehead J. P., Savage D., Wentworth J. M., Chatterjee V. K., O'Rahilly S. (2001) Mol. Endocrinol. 15, 1729–1738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prusty D., Park B. H., Davis K. E., Farmer S. R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 46226–46232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta R. K., Arany Z., Seale P., Mepani R. J., Ye L., Conroe H. M., Roby Y. A., Kulaga H., Reed R. R., Spiegelman B. M. (2010) Nature 464, 619–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Asterholm I. W., Scherer P. E. (2010) Am. J. Pathol. 176, 1364–1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turner N., Grose R. (2010) Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 116–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hutley L., Shurety W., Newell F., McGeary R., Pelton N., Grant J., Herington A., Cameron D., Whitehead J., Prins J. (2004) Diabetes 53, 3097–3106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newell F. S., Su H., Tornqvist H., Whitehead J. P., Prins J. B., Hutley L. J. (2006) FASEB J. 20, 2615–2617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chew C. H., Chew G. S., Najimudin N., Tengku-Muhammad T. S. (2007) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39, 1975–1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Di-Poï N., Desvergne B., Michalik L., Wahli W. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38700–38710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hondares E., Rosell M., Gonzalez F. J., Giralt M., Iglesias R., Villarroya F. (2010) Cell Metab. 11, 206–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adams A. C., Astapova I., Fisher F. M., Badman M. K., Kurgansky K. E., Flier J. S., Hollenberg A. N., Maratos-Flier E. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 14078–14082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]