Abstract

Transcription of HIV-1 genes depends on the RNA polymerase II kinase and elongation factor positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb), the complex of cyclin T1 and CDK9. Recent evidence suggests that regulation of transcription by P-TEFb involves chromatin binding and modifying factors. To determine how P-TEFb may connect chromatin remodeling to transcription, we investigated the relationship between P-TEFb and histone H1. We identify histone H1 as a substrate for P-TEFb involved in cellular and HIV-1 transcription. We show that P-TEFb interacts with H1 and that P-TEFb inhibition by RNAi, flavopiridol, or dominant negative CDK9 expression correlates with loss of phosphorylation and mobility of H1 in vivo. Importantly, P-TEFb directs H1 phosphorylation in response to wild-type HIV-1 infection, but not Tat-mutant HIV-1 infection. Our results show that P-TEFb phosphorylates histone H1 at a specific C-terminal phosphorylation site. Expression of a mutant H1.1 that cannot be phosphorylated by P-TEFb also disrupts Tat transactivation in an HIV reporter cell line as well as transcription of the c-fos and hsp70 genes in HeLa cells. We identify histone H1 as a novel P-TEFb substrate, and our results suggest new roles for P-TEFb in both cellular and HIV-1 transcription.

Keywords: Histone Modification, Histones, HIV, RNA Polymerase II, Transcription Regulation

Introduction

The transcription of many viral and eukaryotic genes is controlled at the point of mRNA elongation by positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb),2 the complex of CDK9 and cyclin T1. This P-TEFb control has been shown in the HIV-1 genes encoding proviral peptides (1, 2), oncogenes such as c-fos (3), and inducible genes such as hsp70 (4). The transcription of these genes is initiated by RNA polymerase II (Pol II), but is inhibited shortly thereafter by Pol II pausing (1, 2). This pause is alleviated by P-TEFb, which increases Pol II processivity by hyperphosphorylating the Ser-2 sites of its C-terminal domain, thus promoting the transition from abortive to productive mRNA elongation (1,2). Importantly, HIV-1 transcription can be prevented by inhibiting P-TEFb phosphorylation of Pol II, such as by siRNA-mediated knockdown of CDK9 or by treating infected cells with the potent CDK9 inhibitor, flavopiridol (5, 6).

Active P-TEFb also binds to multiple chromatin-binding and -modifying proteins such as the bromodomain-containing protein Brd4. Brd4 recruits P-TEFb to promoters by binding both acetylated histone proteins and components of the Mediator complex (7–9). P-TEFb not only interacts with Brd4 at cellular promoters, but also binds specific transcription factors such as NFκB during cellular and HIV transcription (10, 11). Thus, P-TEFb may function in coupling chromatin modification to transcription.

Histone H1 is a highly abundant linker histone protein that binds to nucleosomes and the DNA that connects them (12). H1 facilitates the compaction of chromatin, thus maintaining chromatin patterns during differentiation and development (13, 14). In addition to its role in chromatin compaction, H1 exists in equilibrium between chromatin-bound and -free states (13, 15), with the equilibrium shifting to free H1 when it is phosphorylated (15). H1 is phosphorylated by CDK2 during the G1/S phase transition to promote its dissociation from DNA during DNA replication fork progression (16). Besides this general phosphorylation event, histone H1 phosphorylation may be an important step in the transcription of specific genes. For example, H1 is phosphorylated at the MMTV promoter when transcription is activated and then dephosphorylated when transcription is inhibited (17, 18). However, H1 phosphorylation has not been examined during cellular transcription.

To investigate the role of P-TEFb in coupling chromatin remodeling to transcription, we examined the relationship between P-TEFb and histone H1. We found that P-TEFb phosphorylated the C-terminal domain of histone H1 at S/TPXK consensus sequences important in regulating chromatin binding (19). P-TEFb activity in cell-based assays correlated with H1 phosphorylation as well as H1 dissociation from DNA in the ChIP assay. Additionally expression of a mutant histone H1.1 that is not phosphorylated by P-TEFb also inhibits Tat transactivation of the HIV-1 LTR in a reporter cell line. Because P-TEFb phosphorylation of H1 is necessary for both H1 mobility and HIV-1 transcription, we propose a new role for P-TEFb in transcription as a histone H1 kinase.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression and Purification of P-TEFb

Recombinant baculovirus was generated using BaculoGoldTM DNA (BD Pharmingen), and the plasmid pBAC-HuCDK9-T1 was kindly provided by Dr. D. Price (20). Sf9 cells were infected with recombinant baculovirus, incubated for 3 days, and harvested by centrifugation. The cell pellet was lysed in insect cell lysis buffer (BD Pharmingen) supplemented with insect cell protease inhibitor mixture (BD Pharmingen). The cell lysate was centrifuged 20,000 × g for 45 min. Ni-NTA beads (Qiagen) were added to the supernatant and incubated at 4 °C with constant mixing. The beads were centrifuged at 300 × g and 4 °C for 5 min and applied to a small screening column. The beads were washed, and P-TEFb was isolated using the 6-His purification kit (BD Pharmingen).

Expression of H1.1-His Variants

To assay CDK9 and CDK2 phosphorylation of histone H1.1, we subcloned WT, T152A, and S183A H1.1 from the pEGFP-C1 vector (gifts from M. Hendzel (19, 21, 22)) into the pQET-1 vector. The T152A/S183A H1.1 mutant was made using the Quikchange Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Expression of H1.1-His in BL-21 cells was induced at 25 °C for 8 h using 0.5 mm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. Cells were lysed using 50 mm Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 300 mm NaCl, and 1% Triton X-100, sonicated, and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 18 min. Purified H1.1 was subsequently used as substrate for kinase assays.

In Vitro Kinase Assays

To measure the phosphorylation activity of P-TEFb in vitro, kinase assays were performed with purified P-TEFb and purified histone H1 (Upstate Biotechnologies, Lake Placid, NY) or His-H1.1 fusion proteins. For commercial histone H1 assays, P-TEFb (10 ng) was incubated for 0 to 120 min at 30 °C with 1 μg of histone H1 in P-TEFb kinase buffer (described above) containing a mix of 50 μCi of γ32P-labeled ATP in 3.5 μm cold ATP. For His-H1.1 assays, 50 ng P-TEFb or CDK2/cyclin A (Calbiochem) was incubated with 2 μg of H1.1 for 30 min. Reactions were stopped using Laemmli buffer and run on 4–20% gradient SDS-PAGE. Gels were exposed to phosphor-storage screens, which were scanned using a Fujifilm phosphorimager. Quantitation was performed using ImageGauge software (FujiFilm).

Cell Culture

HeLa cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cell growth was slowed by incubation in serum-starvation medium, DMEM supplemented with 0.5% FBS and 20 mm HEPES pH 7.9, for at least 16 h before lysis. H9 cells were maintained in RPMI medium 1640 (Invitrogen) containing 25 mm HEPES pH 7.9 and l-glutamine with 10% FBS and 100 μg/ml penicillin and streptomycin.

siRNA Transfections

To knock down CDK9, cells were transfected with a custom-designed siRNA (Dharmacon) perfectly matched (5′-UGACGUCCAUGUUCGAGUA-3′) to CDK9 mRNA. CDK2 was targeted using a previously designed and characterized siRNA (5′-AGUUGUACCUCCCCUGGAU-3′) (23). siRNAs (100 nm) were transfected into 4 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates using Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen) in Opti-mem (Invitrogen). Transfection mixes were replaced after 4–6 h with serum-starvation medium, and nuclear extracts were prepared 48 h later.

Transient Plasmid Transfections

For inhibition of P-TEFb in cell culture, we used pCMV-WT and D167N CDK9-HA expression constructs, obtained from Dr. X. Grana (24). Each construct was transfected into HeLa cells using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen), transfection mixes were replaced with serum-starvation medium, and nuclear extracts were prepared 48 h after transfection. For Tat transactivation experiments in MAGI, pCMV-WT, T152A, S183A, S183E, and T152A/S183A GFP-H1.1 or GFP alone were cotransfected with WT or C22G Tat-RFP plasmid into MAGI cells using Lipofectamine.

Drug and UV Treatment

To inhibit CDK9 in vivo, serum-starved HeLa cells were treated with 1–25 nm flavopiridol or vehicle (DMSO) at a final concentration of 0.1% DMSO and incubated overnight. For UV treatment, cells were serum-starved 24–48 h and irradiated as described previously (25). Cells were allowed to recover for 3 h, and nuclear extracts were prepared.

Nuclear Lysates

Nuclear lysates were prepared from cells by washing culture dishes twice with cold PBS, scraping cells from dishes, and lysing with Buffer A (10 mm HEPES pH 7.9, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm KCl, 0.5 mm DTT, and 0.1% Triton X-100) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). Lysates were spun 5 min at 3700 × g and 4 °C in a microfuge. and nuclear pellets were resuspended in Buffer C (30 mm HEPES pH 7.9, 25% glycerol, 0.42 m NaCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm EDTA, and 0.5 mm DTT), incubated for 30 min with mixing at 4 °C, and spun again at 3700 × g for 10 min.

Coimmunoprecipitation

To determine interactions among proteins, nuclei were extracted from treated cells, and target proteins were coimmunoprecipitated using a cyclin T1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Proteins from nuclear extracts (250 μg) were brought to a total volume of 500 μl with PBS. Samples were then incubated with protein A/G beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 30 min after incubation with 2 μg of anti-goat polyclonal cyclin T1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies). Protein A/G beads were washed three times with PBS and boiled in Laemmli buffer.

HIV-1 Infection

To prepare virions, 293T cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) with the pNL-Luc-E−R− strain. At 48 h post-transfection, supernatants were collected, clarified by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min, and filtered through 0.2 μm filters (Pall Corporation). Virus titer was determined using a p24 capsid ELISA kit (Zeptomatrix). For infection of H9 cells, 0.5 μg of pNL4–3-Luc virus or DMEM (mock infection) was incubated with 8 × 105 cells/well of a 12-well plate. Cell suspensions were centrifuged at low speed for 90 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed once with PBS and transferred to H9 medium. Infected cells were incubated at 37 °C for 16–24 h and lysed with M-PER lysis buffer (Pierce Biotechnology). H9 cells infected with the rtTA viral strain were also treated with 5 μg/ml doxycycline (Sigma) to activate transcription.

Western Blotting

Aliquots of total lysate protein (1–10 μg) were separated by 4–12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane using a semidry transfer apparatus (Bio-Rad), and blocked with 5% milk in TBS-T. Membranes were blotted with anti-rabbit cyclin T1, anti-rabbit CDK9, anti-mouse histone H1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), anti-mouse IgM phospho-H1 (Upstate Biotechnologies), anti-mouse RFP (BD Pharmingen), or anti-mouse p24 (AIDS Vaccine Program). Membranes were then washed and incubated with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG-HRP secondary antibody (GE Healthcare) or anti-mouse IgM-HRP secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). SuperSignal West DuraTM HRP Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology) was used for detection. Chemiluminescence images were taken using an Imagereader LAS-3000 LCD camera (FujiFilm).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

ChIP was performed as by the Imbalzano laboratory (26) with the following modifications. HeLa or MAGI cells were crosslinked with 37% formaldehyde for 5 min at room temperature before lysis. Fifty micrograms of lysate were used per immunoprecipitation and were precleared for at least 2 h with protein G-agarose/BSA and salmon sperm DNA (Millipore). Immunoprecipitations were then performed 1 h to overnight with 3 μg of anti-histone H1, clone AE-4 (Millipore), anti-rabbit pH1 (Millipore), anti-histone H3 (Abcam), anti-GAPDH (Novex), or no antibody (mock sample) and collected using protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen). After washing and reversing the crosslinks, DNA was isolated by phenol/chloroform extraction. HIV-1 LTR, β-galactosidase, c-fos, actin, and 18 S binding was determined by qPCR using Absolute Blue qPCR reaction mix (Abgene). Fifty nanograms of purified DNA and a primer concentration of 100 nm was used for each qPCR reaction. Quantitation was performed by a ΔΔCt method: ΔΔCt = Ct sample − Ct Input − Ct mock IP, and H1 enrichment = 2−ΔΔCt.

Detection of mRNAs by qPCR

After treatment of WT, T152A, S183A, S183E, or T152A/S183A GFP-H1.1-expressing HeLa cells with DMSO or flavopiridol, RNA was collected by extraction with Trizol (Invitrogen). Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) was used to generate cDNA from these RNA samples. QPCR was then performed using Absolute Blue qPCR reaction mix (Abgene) using primers to recognize GAPDH, c-Fos, and hsp70 cDNAs. Quantitation was performed using a ΔΔCt method, normalizing to GAPDH signal and WT DMSO-treated samples.

β-Galactosidase Assays

HeLa-MAGI cells were transfected with WT or C22G Tat-RFP and WT, T152A, S183A, S183E, or T152A/S183A GFP-H1.1 plasmids. Cells were then lysed 48 h later using reporter lysis buffer (Promega). Lysates (10 μg) were then incubated overnight with All-in-One β-galactosidase substrate (Pierce). β-Galactosidase activity was measured after incubation by reading absorbance at 405 nm.

RESULTS

P-TEFb Phosphorylates H1 in Vitro and Interacts with H1 in Vivo

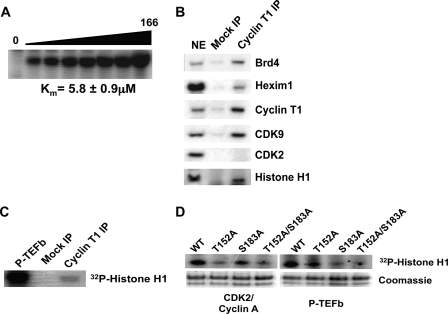

To explore the relationship between P-TEFb and histone H1, we first investigated potential substrates of P-TEFb by performing kinase microarray experiments containing known protein phosphorylation sites. Four separate array experiments showed that P-TEFb phosphorylated H1 isoforms at S/TPXK consensus phosphorylation sites (data not shown). These C-terminal S/TPXK sites, which are normally phosphorylated by CDK2 during the cell cycle, are thought to be important for both C-terminal domain folding and chromatin binding (19, 27). Because of the role of histone H1 binding in chromatin compaction (13) and the necessity of chromatin remodeling for transcription, we examined whether P-TEFb phosphorylates S/TPXK sites in full-length H1 protein. Using in vitro kinase assays, we found that P-TEFb did indeed phosphorylate full-length H1 (Fig. 1A). The Km for this phosphorylation was 5.8 ± 0.9 μm, slightly more than the calculated Km for CDK2 in vitro phosphorylation of H1, 3.4 μm (28).

FIGURE 1.

P-TEFb phosphorylates histone H1 in vitro and interacts with H1 in vivo. A, P-TEFb phosphorylates H1 in vitro. The in vitro kinase activity of purified P-TEFb was assayed with varying concentrations of histone H1. Bands on gel correspond to phosphorylated H1. B, P-TEFb interacts with H1 in vivo. Cyclin T1 was immunoprecipitated from nuclear extracts of HeLa cells, and interaction with CDK9, Brd4, HEXIM1, CDK2, and histone H1 was assessed by Western blot. C, immunoprecipitated P-TEFb phosphorylates H1 in vitro. P-TEFb was immunoprecipitated using a cyclin T1 antibody, and mock IP was performed using anti-goat IgG antibody. IPs were then used in a kinase assay with purified H1. D, CDK2 preferentially phosphorylates Thr-152 of H1.1 in vitro, while P-TEFb preferentially phosphorylates Ser-183 of H1.1 in vitro. Recombinant P-TEFb and CDK2/cyclin A were incubated in a kinase assay with WT, T152A, S183A, and T152A/S183A His-H1.1. Quantification of these results is shown in supplemental Fig. S1.

Next, we examined whether P-TEFb also interacted with H1 in human cells. To that end, endogenous cyclin T1 was immunoprecipitated from nuclear extracts of HeLa cells. We found that endogenous histone H1 as well as CDK9, Brd4, and HEXIM1 coimmunoprecipitated with cyclin T1 (Fig. 1B). Importantly, cyclin T1 did not coimmunoprecipiate CDK2. We then tested the activity of immunoprecipitated P-TEFb on H1 in a kinase assay. P-TEFb immunoprecipitated using a cyclin T1 antibody did phosphorylate H1 in vitro whereas beads from a goat IgG mock IP sample did not (Fig. 1C).

P-TEFb Preferentially Phosphorylates the Ser-183 Phosphorylation Site of Histone H1.1

Because the above experiments showed that P-TEFb interacted with histone H1 in cells and phosphorylated H1 in vitro, we asked whether P-TEFb phosphorylated specific sites on histone H1. To that end, we examined P-TEFb phosphorylation of the H1.1 isoform of histone H1, whose C terminus contains only two (S/T)PXK phosphorylation sites: Thr-152 and Ser-183. Thus, P-TEFb activity at one site could be examined in H1.1 mutated at the other site.

To examine which H1.1 sites P-TEFb and CDK2 preferentially phosphorylate, we purified WT, T152A, S183A, and T152A/S183A mutant His-tagged H1.1 protein and performed in vitro kinase assays. Purified histone H1.1 was incubated with either P-TEFb or CDK2/cyclin A and a mix of unlabeled and γ-32P-labeled ATP, samples were run on SDS-PAGE, and phosphorylation was determined by autoradiography. P-TEFb did indeed phosphorylate T152A H1.1 but phosphorylated S183A less, whereas CDK2 phosphorylated S183A more than T152A H1.1 (Fig. 1D, supplemental Fig. S1). The T152A/S183A double mutant exhibited background phosphorylation for both CDK9 and CDK2. Thus both CDK9 and CDK2 exhibited specificity for different H1.1 sites in vitro.

Histone H1 Phosphorylation in Serum-starved Cells Depends on P-TEFb Activity

Because P-TEFb interacted in vitro with histone H1, we investigated the role of P-TEFb in H1 phosphorylation in vivo. Because histone H1 is predominantly phosphorylated by CDK2 during the G1/S and G2/M phase transitions of the cell cycle (16, 27), we studied CDK9 activity during serum starvation, when CDK2 is likely to be inactive (29). HeLa cells were therefore serum-starved to slow their growth when examining the effect of P-TEFb activity on H1 phosphorylation.

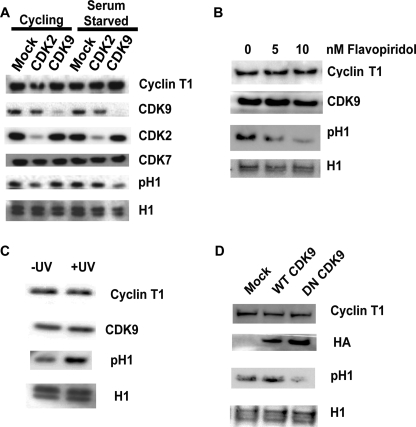

P-TEFb and CDK2 activity is effectively inhibited by siRNA-mediated knockdown (5, 23). To block the expression of CDK9 and CDK2, custom siRNAs were used to target CDK9 or CDK2 mRNA, and we examined H1 phosphorylation in cells grown in medium supplemented with 10% or 0.5% FBS (Fig. 2A, supplemental Fig. S2A). In cells grown in medium containing 10% serum, H1 phosphorylation was reduced in CDK2 knockdown samples but not in mock or CDK9 knockdown cells. However, in serum-starved cells, phosphorylation of H1 was lower in cells transfected with siRNA perfectly matched to CDK9 mRNA than in CDK2 knockdown or mock-transfected cells. Notably, serum-starved cells transfected with CDK2 siRNA had H1 phosphorylation levels comparable to mock-transfected cells. To determine if other CDKs were affected by these siRNAs, we examined the expression of CDK7, a kinase that participates in transcription initiation, whose protein levels remained unchanged. Thus CDK9 knockdown decreased phosphorylation of histone H1 independently of CDK2 in serum-starved cells.

FIGURE 2.

Histone H1 phosphorylation in serum-starved cells depends on the activity of P-TEFb, which interacts with a specific site on histone H1.1. H1 phosphorylation was evaluated in nuclear extracts from cycling or serum-starved HeLa cells by Western blot for cyclin T1, CDK9, phosphorylated H1 (pH1), and total histone H1. A, CDK9 silencing decreases H1 phosphorylation in serum-starved cells independently of CDK2. Cycling and serum-starved HeLa cells were transfected with siRNAs directed against CDK2 or CDK9 mRNA or were mock-transfected, and nuclear extracts were prepared 48 h later. B, CDK9 inhibition blocks H1 phosphorylation. Serum-starved HeLa cells were incubated overnight with 0–10 nm flavopiridol, a potent CDK9 inhibitor, or vehicle (DMSO), and nuclear extracts were prepared 48 h later. C, UV irradiation increases H1 phosphorylation. HeLa cells were serum-starved overnight and then UV treated the following day. Nuclear extracts were prepared 3 h after irradiation. D, expression of enzymatically inactive CDK9 inhibits H1 phosphorylation. HeLa cells were transfected with WT or D167N CDK9-HA, and nuclear extracts were prepared 48 h later. Quantification of these results is presented in supplemental Fig. S2.

To further study the role of P-TEFb activity in H1 phosphorylation, we inhibited CDK9 with flavopiridol, a highly specific CDK inhibitor with IC50 values of 9 nm for CDK9 and greater than 100 nm for CDK2 and other CDKs (6). Therefore, by using low concentrations of flavopiridol, we inhibited CDK9 without affecting other CDKs. Treating serum-starved HeLa cells with 5–10 nm flavopiridol decreased H1 phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2B, supplemental Fig. S2B).

Similarly, we examined H1 phosphorylation after increasing P-TEFb activity in vivo. UV irradiation of cells, performed as previously described (30), releases P-TEFb from the 7SK complex, thus increasing active P-TEFb (31). UV-irradiated cells showed higher levels of H1 phosphorylation than untreated cells (Fig. 2C, supplemental Fig. S2C).

The role of P-TEFb in H1 phosphorylation was also evaluated by overexpressing WT and dominant-negative HA-tagged CDK9. Dominant-negative CDK9, which can still bind cyclin T1, contains a D167N mutation at its catalytic aspartic acid that negates its kinase activity (32). Overexpressing this inactive CDK9 mutant decreased H1 phosphorylation, while WT CDK9 overexpression was comparable to mock-transfected cells (Fig. 2D, supplemental Fig. S2D).

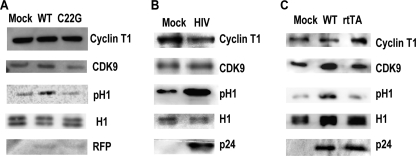

P-TEFb Phosphorylates Host Cell Histone H1 during HIV-1 Infection

Given our results connecting P-TEFb activity with histone H1 phosphorylation in vivo, we examined this interaction in HIV-1-infected cells. P-TEFb is activated in infected cells by HIV-1 Tat, which displaces HEXIM1 from cyclin T1, thus shifting the equilibrium to active P-TEFb (33, 34). To determine whether Tat-mediated activation of P-TEFb induces histone H1 phosphorylation, we first examined H1 phosphorylation in serum-starved HeLa cells in the presence of RFP-tagged wild-type Tat or C22G Tat, which does not bind cyclin T1 (35). In cells expressing WT Tat-RFP, but not C22G Tat-RFP, H1 phosphorylation increased (Fig. 3A, supplemental Fig. S3A). Because expression of Tat on its own activated P-TEFb-mediated H1 phosphorylation, we then evaluated H1 phosphorylation in H9 T cells infected with the pNL4–3 HIV-1 strain. We found much higher levels of phosphorylated H1 in HIV-1-infected cells than in mock-infected cells (Fig. 3B, supplemental Fig. S3B).

FIGURE 3.

Histone H1 is phosphorylated during HIV infection in a Tat-dependent manner. A, H1 phosphorylation is elevated in HeLa cells expressing Tat. HeLa cells were transfected with WT and C22G Tat-RFP expression constructs and serum-starved for 48 h. Nuclear extracts were prepared and evaluated by Western blot analysis for cyclin T1, CDK9, phosphorylated H1 (pH1), total histone H1, and RFP. B, H1 is phosphorylated in T lymphocytes infected with HIV-1. H9 cells were infected with pNL4–3 HIV-1, and lysates were prepared 24 h later. p24 capsid protein was used as a marker for HIV. C, H1 is not phosphorylated in T cells infected with Tat-mutant HIV-1. H9 T cells were infected with WT and Tat rtTA viral constructs, and lysates were prepared 48 h later. Quantitated results are found in supplemental Fig. S3.

Although H1 phosphorylation could be explained by Tat enhancement of P-TEFb activity and activation of HIV-1 transcription, we wanted to ensure that this increase was not due a cellular stress response or viral integration events, as with histone H2AX phosphorylation (36). To address this issue, we used a doxycycline-inducible rtTA strain of HIV-1, which encodes a Y26A mutant Tat that cannot interact with cyclin T1, and an inactive TAR RNA with stem-loop mutations that prevent Tat and cyclin T1 binding (37). H9 cells were infected with either WT pNL4–3 or rtTA HIV-1, and H1 phosphorylation was evaluated. Again, H1 phosphorylation increased in cells infected with WT HIV-1, but not in rtTA-infected or mock-infected cells (Fig. 3C, supplemental Fig. S3C).

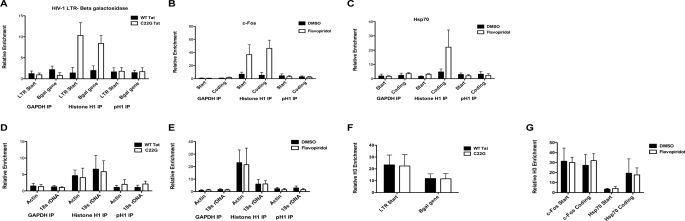

WT Tat Expression in MAGI Cells Causes a Loss of H1 from DNA, and Flavopiridol Treatment of HeLa Cells Results in Increased H1 Binding to the c-Fos and Hsp70 Genes

Because P-TEFb activity correlated with H1 phosphorylation, we wanted to discern whether phosphorylation of histone H1 by P-TEFb released H1 from chromatin. Initial fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments using DMSO or flavopiridol-treated serum-starved cells had shown that P-TEFb inhibition slows GFP-H1.1 recovery and movement in the cell (supplemental Fig. S5A). To that end, we performed ChIP of H1 using MAGI cells transfected with WT or C22G Tat. Binding of H1 to the HIV-1 LTR and β-galactosidase gene was quantitated by qPCR of ChIP DNA fragments. In cells transfected with WT Tat, we observed less amplification of LTR and β-gal fragments relative to cells transfected with C22G Tat, which do not express β-galactosidase (Fig. 4A, supplemental Fig. S6A). However, there was no change in H1 enrichment at the β-actin or 18 S rDNA genes (Fig. 4D). We also did not see a difference in histone H3 binding to the LTR and β-gal gene when we performed ChIP with an antibody to histone H3 (Fig. 4F). ChIP with an antibody directed to phosphorylated H1, which does not bind DNA with high affinity, did not show significant binding either. Therefore, in MAGI cells expressing WT Tat, P-TEFb is recruited to the LTR, and less histone H1 remains bound to DNA.

FIGURE 4.

Active transcription of HIV-1, c-fos, and hsp70 genes causes loss of H1 from DNA. A, P-TEFb-activated transcription from the HIV-1 LTR results in histone H1 dissociation from the HIV-1 LTR and β-galactosidase coding region. MAGI cells were transfected with WT or C22G Tat-RFP and chromatin immunoprecipitation of histone H1, GAPDH, or pH1 was performed 24 h later. To detect regions of DNA bound by H1, qPCR was performed using primers to detect the transcriptional start site of the LTR and the coding region of the βgal gene. Data are reported as fold enrichment above mock IP sample, normalized to input DNA. GAPDH IP was used as a negative control. B and C, inhibition of P-TEFb by flavopiridol causes an accumulation of histone H1 at c-fos and hsp70 coding region. HeLa cells were treated overnight with 25 nm flavopiridol, and chromatin immuoprecipitation of histone H1 or GAPDH was performed the following day. qPCR was performed using DNA isolated from the immunoprecipitations. D, Tat expression in MAGI does not cause a release of H1 from the β-actin and 18 S genes. H1 and GAPDH ChIP and qPCR were performed as described above. E, inhibition of P-TEFb by flavopiridol does not cause an enrichment of H1 from the β-actin and 18 S genes. H1 and GAPDH ChIP was performed after HeLa cells were treated overnight with flavopiridol. F, histone H3 binding at the HIV-1 LTR start site and β-galactosidase coding region does not change during transcription from the LTR in MAGI cells. MAGI cells were transfected with either WT or C22G Tat-RFP and chromatin IP of histone H3 was performed 24 h later. G, histone H3 binding to the c-fos or hsp70 start site and coding region does not change when P-TEFb is inhibited. HeLa cells were treated overnight with DMSO or 25 nm flavopiridol and histone H3 chromatin IP was performed the following day.

In addition to H1 binding at the HIV-1 LTR, we wanted to assess H1 binding at cellular genes that require P-TEFb for transcription. By performing H1 ChIP on cells treated overnight with DMSO or flavopiridol, we could then directly determine H1 binding during active and inactive transcription. For these experiments, we chose to examine c-fos and hsp70, immediate early genes that are sensitive to P-TEFb activity (3) (supplemental Fig. S6B). We therefore immunoprecipitated histone H1 from HeLa treated with DMSO or 25 nm flavopiridol, and examined binding to the c-fos and hsp70 transcription start sites and coding regions. When P-TEFb is inhibited using flavopiridol, there is more H1 bound at both the c-fos start region and downstream coding region compared with DMSO-treated samples (Fig. 4B). Likewise, more H1 is bound to the hsp70 coding region when P-TEFb is inhibited. Because of the low levels of H1 bound to the hsp70 start site we were not able to detect a significant difference in the presence of flavopiridol. Notably, H1 enrichment does not decrease at the β-actin or 18 S genes when P-TEFb was inhibited (Fig. 4D). While there was a change in H1 enrichment at the c-fos and hsp70 genes, we saw no difference in histone H3 binding (Fig. 4F). Again, pH1 ChIP did not show significant enrichment in either gene.

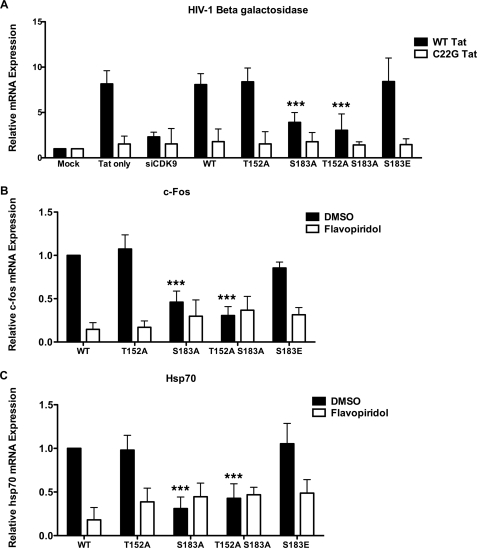

Phosphorylation of Histone H1.1 Ser-183 Is Necessary for Both Transcription from the HIV-1 LTR and Transcription of the c-Fos and Hsp70 Genes

In vitro kinase assays indicated that Ser-183 is important for P-TEFb phosphorylation. FRAP studies using GFP-histone H1.1 taught us that P-TEFb activity in serum-starved cells can control the rate of exchange of histone H1 on chromatin, and mutation of the Ser-183 site to alanine decreased its recovery time (supplemental Fig. S5B). Taking these data together with our ChIP data, which showed a release of H1 from sites of P-TEFb-dependent transcription, we hypothesized that S183A H1.1 expression would have a negative effect on transcription. To examine whether H1 phosphorylation plays a role in HIV transcription, we expressed WT, T152A, S183A, or S183E GFP-H1.1 and WT or C22G Tat-RFP in MAGI cells. To quantify HIV transcription, we measured β-galactosidase activity 48 h post-transfection. While expression of WT and T152A H1.1 had no effect on Tat transactivation, expression of the S183A mutant caused a decrease in β-galactosidase expression (Fig. 5A). The S183E mutant, which mimics phosphorylation of Ser-183 with negative charge, also had no negative effect on β-galactosidase expression. In the presence of C22G Tat and S183E H1.1, there was little β-galactosidase expression, presumably because P-TEFb could not be recruited to Pol II by the Tat/TAR complex.

FIGURE 5.

S183A GFP-histone H1 expression inhibits P-TEFb activation of HIV-1, c-fos, and Hsp70 transcription. A, S183A GFP-H1.1 expression in MAGI cells reduces Tat-activated HIV transcription. MAGI cells were transfected with WT or C22G Tat-RFP and WT, T152A, S183A, T152A/S183A, or S183E GFP-H1.1. Cell lysates were taken and β-galactosidase activity was measured 48 h post-transfection. B and C, S183A GFP-H1.1 expression in HeLa cells results in reduced c-Fos (B) and Hsp70 (C) mRNA expression and insensitivity to flavopiridol. WT, T152A, S183A, S183E, or T152A/S183A GFP-H1.1 HeLa cells were treated with DMSO or 25 nm flavopiridol overnight, and mRNAs were isolated the following day. qPCR was performed to detect c-Fos and Hsp70 normalized to GAPDH message. *** signifies a p-value of <0.001.

Because expression of the S183A H1.1 mutant had a negative effect on HIV-1 transcription, we wanted to assess the effect this mutant H1 isoform had on endogenous transcription controlled by P-TEFb. To that end, we isolated RNA from cells transfected with GFP-tagged WT, T152A, S183A, or T152A/S183A H1.1, and performed qPCR with primer sets to detect GAPDH and c-Fos, or Hsp70, two genes whose transcription is dependent upon P-TEFb (3, 38). After normalizing the data to GAPDH signal, we found that both c-Fos and Hsp70 transcription is lower in S183A H1.1 cells relative to WT, T152A, or S183E cells (Fig. 5, B and C). The double mutant T152A/S183A did not demonstrate a greater reduction in c-Fos and Hsp70 transcription than the S183A mutant. Moreover, when these cells were treated with 25 nm flavopiridol, the levels of c-Fos and Hsp70 transcripts in the S183A and T152A/S183A H1.1 cells did not change, while GFP-WT, T152A, and S183E H1.1 cells were sensitive to flavopiridol. Elimination of the Ser-183 phosphorylation site of histone H1.1 therefore diminishes P-TEFb-regulated transcription of c-Fos and Hsp70 mRNAs.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that the activity of P-TEFb correlates with in vivo phosphorylation of histone H1 and its dissociation from DNA. P-TEFb mediated H1 phosphorylation in a Tat-specific manner in both HeLa cells transfected with Tat and in HIV-1 infected H9 cells. Furthermore, P-TEFb phosphorylated the H1.1 isoform at a specific C-terminal phosphorylation site to enhance histone mobility and transcription from the HIV-1 LTR and the c-fos and hsp70 genes. As determined by ChIP, active transcription from the HIV-1 LTR in MAGI cells and the c-fos and hsp70 genes in HeLa cells resulted in a release of H1 from their respective transcriptional start sites and downstream coding regions. Taken together, our results imply histone H1 is a novel substrate for P-TEFb, suggesting a new role for this elongation factor in RNA Pol II transcription.

In this study, we have identified histone H1 as a potential substrate of P-TEFb both in vitro and in cell culture. Inhibiting P-TEFb activity by specific knockdown with siRNA, chemical inhibition by flavopiridol, or overexpression of dominant-negative CDK9 all decreased H1 phosphorylation. Conversely, releasing P-TEFb from its inactive complex with 7SK and HEXIM1/2, e.g. by UV irradiation or Tat expression, increased levels of phosphorylated H1. These experiments were performed in serum-starved cells to slow their growth, ensuring that CDK9 was active while CDK2 was inactive (29). In sum, these data imply that P-TEFb phosphorylates H1 in the cell.

In addition to the dependence of histone H1 phosphorylation on P-TEFb activity, our data also indicate that H1 is phosphorylated in a Tat-dependent manner during HIV-1 infection. Because Tat is necessary to increase H1 phosphorylation during HIV-1 infection, this phosphorylation may be important in activating HIV-1 transcription. Moreover, H1 phosphorylation did not increase in cells infected with a Tat-mutant viral strain, ruling out the possibility that H1 was phosphorylated simply as part of a cellular stress response induced by the virus during integration. Since this mutant virus transcribes host DNA independently of Tat and P-TEFb, H1 phosphorylation during HIV-1 infection may be specific to Tat- and P-TEFb-mediated transcription. Because Tat activates the transcription of cellular genes in addition to viral genes (39–41), Tat and P-TEFb may also have synergistic effects on H1 phosphorylation at both cellular and HIV genes.

It is important to note that while we characterize H1 phosphorylation as a function of P-TEFb activity, there is a possibility that this effect is indirect. However, the methods used here specifically inhibit or activate P-TEFb independently of other kinases.

Having shown that P-TEFb phosphorylates histone H1 in vitro, we asked whether a specific site on histone H1 was phosphorylated. Although P-TEFb could phosphorylate multiple H1 isoforms, we used the H1.1 isoform because its two phosphorylation sites can be studied independently. Using histone H1.1 phosphorylation site mutants, we found that P-TEFb preferentially phosphorylates WT and T152A H1.1 in vitro. Additionally, S183A H1.1 expression in MAGI cells prevented full transactivation of the HIV-1 LTR, while WT, T152A, and the phosphorylation mimic S183E did not affect β-galactosidase expression. Importantly, the S183E mutant was sensitive to C22G Tat expression because the P-TEFb complex is not recruited to the LTR to phosphorylate Pol II. HeLa cells expressing GFP-S183A H1.1 also expressed lower levels of c-Fos and Hsp70 mRNA and were insensitive to flavopiridol treatment. The S183E phosphorylation mimic, however, did not reduce c-Fos and Hsp70 transcription and was sensitive to flavopiridol treatment because the prior step of Pol II phosphorylation is inhibited.

Taken together, we surmise that P-TEFb preferentially phosphorylates Ser-183 in vivo. This specificity of P-TEFb for Ser-183 contrasts with previous results, suggesting that in actively dividing cells Thr-152 is preferentially phosphorylated by other CDKs (19). We also found that CDK2 preferentially phosphorylates WT and S183A H1.1 in vitro. Each H1.1 site could therefore be phosphorylated under different cellular conditions and during different processes, i.e. cellular replication or transcription. Whereas H1 is phosphorylated by CDK2 on a global scale at all genes (16), we observed changes in H1 enrichment at P-TEFb-specific genes but not β-actin or 18 S, which are constitutively expressed.

Our results also show the potential function of P-TEFb phosphorylation of H1, namely, to increase H1 dissociation from actively transcribed DNA. The movement of histone H1 is inversely proportional to the stability of H1-chromatin binding (21, 22). Likewise, GFP-H1.1 recovered more slowly in serum-starved cells treated with flavopiridol than in DMSO-treated control cells (supplemental Fig. 5A). Because decreased mobility of H1 has been correlated with its increased binding to DNA (21, 22), P-TEFb inhibition likely stabilized H1 binding to chromatin. To test this hypothesis, we performed histone H1 ChIP assays. In WT Tat-transfected MAGI cells, we observed a loss of H1 at both the LTR transcription start site and a downstream coding region of the β-galactosidase gene compared with C22G Tat-transfected cells. Likewise, when flavopiridol was used to inhibit P-TEFb in HeLa cells, more H1 was bound to the transcription start site and downstream coding region of the c-Fos gene than when cells were treated with DMSO alone. The loss of H1 at these sites of active P-TEFb-mediated transcription supports the mechanism suggested by the H1 FRAP data, namely, that P-TEFb phosphorylation of H1 leads to its dissociation from DNA.

Upon seeing the effect of WT Tat and P-TEFb together on H1 phosphorylation, and knowing the effect of P-TEFb activity on H1 mobility and DNA binding, we wanted to ascertain the importance of H1 phosphorylation for P-TEFb-mediated transcription. We found that S183A H1.1 expression suppresses WT Tat transactivation, c-Fos and Hsp70 transcription compared with cells expressing WT, T152A, or the phosphorylation mimic S183E H1.1. From these data, we can deduce that P-TEFb phosphorylation of histone H1 might be a necessary step in the transcription of HIV genes as well as cellular genes that need active P-TEFb to be expressed.

The control of gene expression via H1 phosphorylation has been noted, and regulation of the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter is the most well-studied example (18). Here we show the effect of P-TEFb-mediated phosphorylation of H1 on gene expression.

Additionally, P-TEFb is known to interact with proteins that bind and modify chromatin, and we report a specific and functionally relevant interaction between P-TEFb and histone H1. P-TEFb is recruited to cellular promoters by the bromodomain-containing protein Brd4 (8,9), and phosphorylation of the Pol II C-terminal domain by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homolog of CDK9 recruits the Set2 histone methyltransferase (42, 43). This recruitment results in H3K36 methylation, marking chromatin at sites of Pol II elongation. Taking our data into account, H1 phosphorylation could potentially aid in chromatin remodeling by allowing chromatin modifying machinery to access nucleosomes. This increased accessibility would allow Pol II to transcribe through chromatin more efficiently.

Based on our results, we propose a model in which P-TEFb phosphorylates histone H1 during Pol II transcription. When activated from the 7SK/HEXIM complex, P-TEFb would be recruited to phosphorylate Pol II complexes thereby promoting elongation. P-TEFb would also phosphorylate H1 concomitantly with Pol II transcription, increasing the processivity of the polymerase.

In summary, here we identify histone H1 as a substrate of P-TEFb and suggest a novel role for P-TEFb during elongation. Because P-TEFb phosphorylation of H1 could destabilize the interaction of H1 with chromatin, transcribed genes may be more readily remodeled. Our results describe a new mechanism of P-TEFb function in regulating the expression of both cellular and HIV-1 genes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Ben Berkhout, Xavier Graña, Michael Hendzel, David Price, and Qiang Zhou for kindly providing reagents. We thank members of the Rana and Knight laboratories for helpful discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6.

- P-TEFb

- positive transcription elongation factor b

- CDK

- cyclin-dependent kinase

- FRAP

- fluorescence recovery after photobleaching.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhou Q., Yik J. H. (2006) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70, 646–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peterlin B. M., Price D. H. (2006) Mol. Cell 23, 297–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryser S., Fujita T., Tortola S., Piuz I., Schlegel W. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5075–5084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ni Z., Schwartz B. E., Werner J., Suarez J. R., Lis J. T. (2004) Mol. Cell 13, 55–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiu Y. L., Cao H., Jacque J. M., Stevenson M., Rana T. M. (2004) J. Virol. 78, 2517–2529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chao S. H., Fujinaga K., Marion J. E., Taube R., Sausville E. A., Senderowicz A. M., Peterlin B. M., Price D. H. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 28345–28348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu S. Y., Chiang C. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 13141–13145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jang M. K., Mochizuki K., Zhou M., Jeong H. S., Brady J. N., Ozato K. (2005) Mol. Cell 19, 523–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Z., Yik J. H., Chen R., He N., Jang M. K., Ozato K., Zhou Q. (2005) Mol. Cell 19, 535–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amini S., Clavo A., Nadraga Y., Giordano A., Khalili K., Sawaya B. E. (2002) Oncogene 21, 5797–5803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barboric M., Nissen R. M., Kanazawa S., Jabrane-Ferrat N., Peterlin B. M. (2001) Mol. Cell 8, 327–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodcock C. L., Skoultchi A. I., Fan Y. (2006) Chromosome Res. 14, 17–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bustin M., Catez F., Lim J. H. (2005) Mol. Cell 17, 617–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan Y., Nikitina T., Zhao J., Fleury T. J., Bhattacharyya R., Bouhassira E. E., Stein A., Woodcock C. L., Skoultchi A. I. (2005) Cell 123, 1199–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Catez F., Ueda T., Bustin M. (2006) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 305–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexandrow M. G., Hamlin J. L. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 168, 875–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhattacharjee R. N., Archer T. K. (2006) Virology 346, 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee H. L., Archer T. K. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 1454–1466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hendzel M. J., Lever M. A., Crawford E., Th'ng J. P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 20028–20034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng J., Marshall N. F., Price D. H. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 13855–13860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lever M. A., Th'ng J. P., Sun X., Hendzel M. J. (2000) Nature 408, 873–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Misteli T., Gunjan A., Hock R., Bustin M., Brown D. T. (2000) Nature 408, 877–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du J., Widlund H. R., Horstmann M. A., Ramaswamy S., Ross K., Huber W. E., Nishimura E. K., Golub T. R., Fisher D. E. (2004) Cancer Cell 6, 565–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garriga J., Mayol X., Grana X. (1996) Biochem. J. 319, 293–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yik J. H., Chen R., Nishimura R., Jennings J. L., Link A. J., Zhou Q. (2003) Mol. Cell 12, 971–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salma N., Xiao H., Mueller E., Imbalzano A. N. (2004) Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 4651–4663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Contreras A., Hale T. K., Stenoien D. L., Rosen J. M., Mancini M. A., Herrera R. E. (2003) Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 8626–8636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gondeau C., Gerbal-Chaloin S., Bello P., Aldrian-Herrada G., Morris M. C., Divita G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 13793–13800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garriga J., Bhattacharya S., Calbó J., Marshall R. M., Truongcao M., Haines D. S., Graña X. (2003) Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 5165–5173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen V. T., Kiss T., Michels A. A., Bensaude O. (2001) Nature 414, 322–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michels A. A., Fraldi A., Li Q., Adamson T. E., Bonnet F., Nguyen V. T., Sedore S. C., Price J. P., Price D. H., Lania L., Bensaude O. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 2608–2619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garriga J., Segura E., Mayol X., Grubmeyer C., Graña X. (1996) Biochem. J. 320, 983–989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sedore S. C., Byers S. A., Biglione S., Price J. P., Maury W. J., Price D. H. (2007) Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 4347–4358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barboric M., Yik J. H., Czudnochowski N., Yang Z., Chen R., Contreras X., Geyer M., Matija Peterlin B., Zhou Q. (2007) Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 2003–2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garber M. E., Wei P., KewalRamani V. N., Mayall T. P., Herrmann C. H., Rice A. P., Littman D. R., Jones K. A. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 3512–3527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie A., Scully R. (2007) Mol. Cell 27, 178–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verhoef K., Marzio G., Hillen W., Bujard H., Berkhout B. (2001) J. Virol. 75, 979–987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lis J. T., Mason P., Peng J., Price D. H., Werner J. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 792–803 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de la Fuente C., Santiago F., Deng L., Eadie C., Zilberman I., Kehn K., Maddukuri A., Baylor S., Wu K., Lee C. G., Pumfery A., Kashanchi F. (2002) BMC Biochemistry 3, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Izmailova E., Bertley F. M., Huang Q., Makori N., Miller C. J., Young R. A., Aldovini A. (2003) Nat. Med. 9, 191–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romani B., Engelbrecht S., Glashoff R. H. (2010) J. Gen. Virol. 91, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keogh M. C., Kurdistani S. K., Morris S. A., Ahn S. H., Podolny V., Collins S. R., Schuldiner M., Chin K., Punna T., Thompson N. J., Boone C., Emili A., Weissman J. S., Hughes T. R., Strahl B. D., Grunstein M., Greenblatt J. F., Buratowski S., Krogan N. J. (2005) Cell 123, 593–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krogan N. J., Baetz K., Keogh M. C., Datta N., Sawa C., Kwok T. C., Thompson N. J., Davey M. G., Pootoolal J., Hughes T. R., Emili A., Buratowski S., Hieter P., Greenblatt J. F. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 13513–13518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.