Abstract

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined as any degree of glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy. Women with GDM and their offspring have an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus in the future. The global incidence of GDM is difficult to estimate, due to lack of uniform diagnostic criteria. Various diagnostic criteria have been proposed. The benefit of treating GDM has also been controversial. The clinical significance of treating maternal hyperglycemia was made evident in the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes (HAPO) study. The HAPO study demonstrated that there is a continuous association of maternal glucose levels with adverse pregnancy outcomes and served as the basis for a new set of diagnostic criteria, proposed in 2010 by the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Groups (IADPSG). According to these criteria the diagnosis of GDM is made if there is at least one abnormal value (≥92, 180 and 153 mg/dl for fasting, one-hour and two-hour plasma glucose concentration respectively), after a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT).

Keywords: gestational diabetes mellitus, diagnosis, diagnostic criteria, HAPO study, International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Groups (IADPSG), review

For many years, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) has been defined as "any degree of glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy"1. According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), it complicates approximately 7% of all pregnancies1, whereas its total incidence is estimated up to 17.8%2. Women who have had GDM have at least a seven-fold increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus in the future3. Moreover, the presence of a hyperglycemic intrauterine enviroment due to GDM is associated with the development of type 2 diabetes in the offspring4. Additionally, there is evidence that women with GDM are less likely to breastfeed and that breastfeeding improves the subsequent glucose tolerance of the mother and may reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes in children5. Even though GDM is a common disorder in pregnancy, it has been difficult to compare its frequency among various populations and estimate its global incidence, due to the lack of uniform diagnostic criteria6.

What are the existing diagnostic criteria?

O' Sullivan and Mahan in 1964 proposed the first diagnostic criteria for GDM, assaying whole blood glucose with the Somogyi-Nelson method, during a three-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)7. Glucose levels of 90, 165, 145 and 125 mg/dl (for fasting, one-hour, two-hour and three-hour postglucose load respectively) were proposed as diagnostic thresholds for GDM. More than a decade later, in 1979, the National Diabetes Data Group (NDDG) suggested measuring plasma instead of whole blood glucose and set new threshold values (105, 190, 165 and 145 mg/dl)8. In 1982, Carpenter and Coustan proposed changing the values to 95, 180, 155 and 140 mg/dl9. According to the NDDG and Carpenter and Coustan criteria, the diagnosis of GDM is established if two or more glucose values are higher than the defined cutoffs during a three-hour OGTT. In 1989, Sacks et al proposed the more inclusive criteria of 96, 172, 152 and 131 mg/dl, after calculating glucose concentrations in paired whole blood and plasma specimens of 995 consecutive pregnant women10.

All the aforementioned diagnostic thresholds were based on data from women who were diagnosed with diabetes after gestation and not on any short-term adverse pregnancy outcomes. In 2010, the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Groups (IADPSG) proposed a new set of criteria, based on the incidence of adverse perinatal outcomes, as assessed in the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes (HAPO) study11,12. According to these criteria, the diagnosis of GDM is made if at least one value of plasma glucose concentration is equal to or exceeds the thresholds of 92, 180 and 153 mg/dl (for fasting, one-hour and 2-hour postglucose load glucose values respectively), after performing a 75 g OGTT2.

To treat or not to treat?

The rationale of screening for GDM is based on the assumption that treating the condition leads to a decrease in maternal or fetal complications. The effect of GDM treatment on fetal and maternal outcomes has long been controversial. According to a 2003 Cochrane Collaboration systematic review "there are insufficient data for any reliable conclusions about the effects of treatments for impaired glucose tolerance on perinatal outcome"13. Data from two pilot randomized controlled trials suggested that intensive GDM treatment had no statistically significant effect on various perinatal outcomes14,15. The first study, by Garner et al14, included 300 women between 24 and 32 weeks of gestation, who were diagnosed with GDM according to the Hatem et al criteria16, following a 75 g OGTT. Women were randomized either to strict glycemic control and tertiary care, or to routine obstretic care. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in birth weight or in any of the secondary outcomes, including neonatal hypoglycemia, birth trauma, perinatal mortality and cesarean section rates. In a similar study by Bancroft et al, 68 pregnant women with impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) were randomly assigned15 to either intensified or standard antenatal care. No statistically significant differences were found in any neonatal or maternal outcomes between the groups. However, both pilot trials lacked sufficient power to detect differences in the measured outcomes and they both suffered from ineffective blinding.

The clinical significance of treating GDM with respect to various adverse perinatal outcomes has been demonstrated by Langer et al in an observational case-control study of 2775 pregnant women17- 555 with untreated GDM, 1110 with treated GDM and 1110 non-diabetic controls. Diagnosis of GDM was based on the criteria by Carpenter-Coustan9. Rates of a composite adverse outcome (stillbirth, neonatal macrosomia/large-for-gestational- age (LGA), neonatal hypoglycemia, erythrocytosis and hyperbilirubinemia) in the three groups were 59%, 18% and 11%, respectively. More robust evidence concerning the reduction of risk of perinatal complications following treatment of GDM was provided by the Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study in Pregnant Women (ACHOIS)18 and a trial conducted by Landon et al19. In each of these randomized controlled trials, approximately 1000 women with GDM were assigned either to prenatal dietary advice, blood glucose monitoring and insulin therapy (treatment group), or to routine care (control group). The incidence of various predefined perinatal outcomes, including LGA births and preeclampsia, was significantly reduced in the treatment group in both trials18,19. However, there were differences in the GDM diagnostic criteria used in each of the studies, hence the study population, was not identical in the two trials. The first study to provide solid evidence of a direct association between maternal glucose levels and pregnancy outcome, irrespective of the diagnosis of GDM, was the HAPO study11,12.

The HAPO study

The HAPO study was a large multinational prospective study that included 25505 women in the third trimester of gestation11. The participants underwent a two-hour OGTT with 75 g of glucose between 24 and 32 weeks of gestation and their glycemic levels were investigated in relation to predefined adverse pregnancy outcomes. The four predifined primary outcomes were primary cesarean delivery, clinical neonatal hypoglycemia, and birth weight and cord serum C-peptide above the 90th percentile. Premature delivery, shoulder dystocia or birth injury, intensive neonatal care, hyperbilirubinemia, and preeclampsia were chosen as secondary outcomes. In respect to secondary outcomes, glucose levels were analyzed only as a continuous variable. For the primary outcomes, glucose concentration was also analyzed as a categorical variable, after stratifying the women into seven categories according to the glucose values obtained during the two-hour OGTT.

The frequency of the primary outcomes increased in parallel with increasing maternal glucose levels and odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for all seven glycemic categories, using as reference (OR=1) the category with the lowest glucose concentration ranges. The ORs increased across the categories of maternal glycemia and these results were statistically significant for all primary outcomes, with the exception of neonatal hypoglycemia. Similarly, when glucose concentration was analyzed as a continuous variable, a continuous association of maternal glucose with primary and secondary outcomes was observed. Notably, these associations were detected even for low glucose levels and did not differ among the 15 centers in nine countries that participated in the study11.

Even though the HAPO study indicated the need to revise the diagnostic criteria of GDM, it did not deduce any threshold glucose values that can be used in clinical practice. Therefore, even after completion of the study, screening and diagnostic methods of GDM still differ among various associations and organizations.

ADA, ACOG, WHO and IDF recommendations

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) in its more recent position statement suggests that all pregnant women should be screened for GDM between the 24th and 28th week of gestation, unless they are of low risk status1. Women of low risk are defined as those that fulfill all of the following characteristics: age below 25 years, normal pregestational weight, member of an ethnic group with low prevalence of diabetes, no history of glucose intolerance and poor obstetrical outcome, and no known diabetes in first degree relatives. Two approaches are suggested for screening for GDM (at 24-28 weeks). In the two-step approach, women are initially screened by measuring plasma glucose 1 hour after a 50 g glucose load; women with glucose concentration ≥130 or ≥140 mg/dl (depending on the diagnostic sensitivity we wish to achieve) undergo an 100 g OGTT on a separate day. In the one-step approach, the 100 g OGTT is performed directly without any initial screening. In both occasions, the diagnosis of GDM is established by the Carpenter and Coustan criteria.

The American Council of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) also suggests screening of all women except for those of low risk status20. It supports the use of the 100 g OGTT and application of either NDDG or Carpenter and Coustan criteria. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends using the 75 g two-hour OGTT and the diagnostic thresholds of 126 mg/dl and 140 mg/dl for fasting and 2-hour glucose concentrations, respectively21. Finally, according to the 2009 International Diabetes Federation (IDF) recommendations, women who are at high risk (history of previous GDM) should undergo an OGTT as soon as possible22. For all other women the OGTT should be performed between the 26th and 28th week of gestation. In both cases, a one-stage procedure with the 75 g OGTT is preferred.

Due to the lack of uniform diagnostic criteria for more than 40 years, there has been no global consensus about the appropriate screening/diagnostic test, whether it should be applied selectively or to all pregnant women and about the diagnostic thresholds of each test. ADA1, IDF22 and other organizations are expected to consider adopting the recently proposed IADPSG diagnostic criteria2.

IADPSG recommendations

The IADPSG was formed "as an umbrella organization to facilitate collaboration between the various regional and national groups that have a primary or significant focus on diabetes and pregnancy"2. In 2010, the IADPSG proposed a new set of diagnostic criteria for GDM, based on the results of the HAPO study11,12, thus association of maternal glucose concentration with the risks for birth weight, cord C-peptide and % neonatal body fat to be above the 90th percentile. Mean values for fasting, one-hour, and two-hour OGTT plasma glucose of the entire study population were used as reference for calculation of ORs. An OR of 1.75 was prespecified by the IADPSG consensus panel as a threshold to define the diagnostic criteria. The values that correspond to this OR are 92, 180, and 153 mg/dl for fasting, one-hour, and two-hour OGTT plasma glucose concentrations, respectively. These cutoff points represent the glucose concentrations at which odds for birth weight, cord C-peptide and % neonatal body fat to be above the 90th percentile are 1.75 times the odds of these outcomes at reference glucose values (mean glucose values)2. The diagnosis of GDM is made if one or more glucose values during a 75 g OGTT meet or exceed the above thresholds. According to these criteria, the incidence of GDM in the overall population in the HAPO study was 17.8%. When ORs of 1.5 and 2.0 were used as thresholds, the percentage of women that met the diagnostic criteria was 25% and 8.8%, respectively2.

For the identification of overt diabetes during pregnancy and its distinction from GDM, the IADPSG recommends that fasting plasma glucose (FPG) or glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C) should be measured at the first prenatal visit on all or only high-risk women (depending on the frequency of diabetes in the background population and on local cicrumstances)2. Values equal to or above 126 mg/dl and 6.5% (for FPG and A1C, respectively) establish the diagnosis of overt diabetes. Women with 92≤ FPG <126 mg/dl are diagnosed with GDM, while those with FPG<92 mg/dl should undergo a 75 g OGTT at 24 to 28 weeks of gestation. Finally, the diagnosis of GDM by means of the 75 g OGTT is based on the aforementioned criteria (92, 180, and 153 mg/dl for fasting, one-hour, and two-hour OGTT glucose concentrations, respectively)2.

Concluding remarks

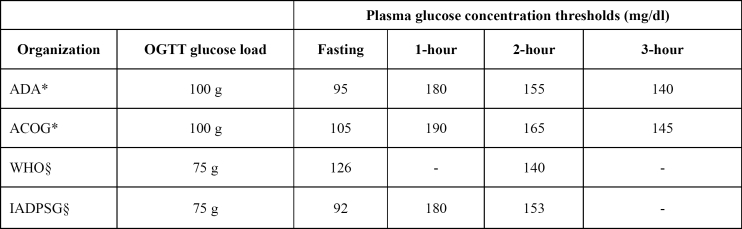

Lack of uniform diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus has often led to misconceptions and undertreatment of GDM. The diagnostic threshold values of various organizations are summarized in Table 1. The recently proposed IADPSG criteria are based on the results of the HAPO study, which demonstrated a continuous association of maternal glycemia with adverse pregnancy outcomes. The IADPSG consensus panel consisted of leading experts in the field of GDM from a variety of countries, hence their recommendations are expected to "serve as the basis for internationally endorsed criteria for the diagnosis and classification of diabetes in pregnancy" 2, as stated in its 2010 report. The IADPSG suggests screening in all women at the first prenatal visit and a 75 g OGTT between the 24th and 28th week of gestation in those not already diagnosed with overt diabetes or GDM by early testing. One or more abnormal value (≥ 92, 180 or 153 mg/dl for fasting, 1-hour and 2-hour plasma glucose, respectively) after a 75 g OGTT is diagnostic of GDM. However, as a result of using these criteria, the total incidence of GDM, hence its total therapeutic costs will increase. Thus, additional randomized clinical trials are required in order to determine the cost-effectiveness of the IADPSG criteria and their association with longterm development of diabetes mellitus and metabolic disorders in the mother and the offspring2.

Table 1. GDM diagnostic threshold values from various organizations.

*Diagnosis of GDM if two or more glucose values equal to or exceeding the threshold values §Diagnosis of GDM if one or more glucose values equal to or exceeding the threshold values GDM: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus, OGTT: Oral Glucose Tolerance Test, ADA: American Diabetes Association, ACOG: American Council of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, WHO: World Health Organization, IADPSG: International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Groups

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes - 2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:S11–S16. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:676–682. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:1773–1779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clausen TD, Mathiesen ER, Hansen T, Pedersen O, Jensen DM, Lauenborg J. High prevalence of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes in adult offspring of women with gestational diabetes mellitus or type 1 diabetes: the role of intrauterine hyperglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:340–346. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor JS, Kacmar JE, Nothnagle M, Lawrence RA. A systematic review of the literature associating breastfeeding with type 2 diabetes and gestational diabetes. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005;24:320–326. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2005.10719480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-Haroush A, Yogev Y, Hod M. Epidemiology of gestational diabetes mellitus and its association with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2004;21:103–113. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.OSullivan JB, Mahan CM. Criteria for the Oral Glucose Tolerance Test in Pregnancy. Diabetes. 1964;13:278–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Diabetes Data Group. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. Diabetes. 1979;28:1039–1057. doi: 10.2337/diab.28.12.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpenter MW, Coustan DR. Criteria for screening tests for gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;144:768–773. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sacks DA, Abu-Fadil S, Greenspoon JS, Fotheringham N. Do the current standards for glucose tolerance testing in pregnancy represent a valid conversion of OSullivans original criteria? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:638–641. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90369-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Dyer AR, Trimble ER, Chaovarindr U, Coustan DR, et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1991–2002. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study: associations with neonatal anthropometrics. Diabetes. 2009;58:453–459. doi: 10.2337/db08-1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuffnell DJ, West J, Walkinshaw SA. Treatments for gestational diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003395. CD003395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garner P, Okun N, Keely E, Wells G, Perkins S, Sylvain J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of strict glycemic control and tertiary level obstetric care versus routine obstetric care in the management of gestational diabetes: a pilot study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:190–195. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bancroft K, Tuffnell DJ, Mason GC, Rogerson LJ, Mansfield M. A randomised controlled pilot study of the management of gestational impaired glucose tolerance. BJOG. 2000;107:959–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb10396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatem M, Anthony F, Hogston P, Rowe DJ, Dennis KJ. Reference values for 75 g oral glucose tolerance test in pregnancy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988;296:676–678. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6623.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langer O, Yogev Y, Most O, Xenakis EM. Gestational diabetes: the consequences of not treating. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:989–997. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, McPhee AJ, Jeffries WS, Robinson JS. Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2477–2486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landon MB, Spong CY, Thom E, Carpenter MW, Ramin SM, Casey B, et al. A multicenter, randomized trial of treatment for mild gestational diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1339–1348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 30, September 2001 (replaces Technical Bulletin Number 200, December 1994). Gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:525–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539–553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.IDF Clinical Guidelines Task Force. Global Guideline on Pregnancy and Diabetes. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2009. Available from: http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/Pregnancy_EN_RTP.pdf. [Google Scholar]