Abstract

Purpose of Review

To provide a state-of-the-science review of the literature on secondary prevention of HIV infection, or “prevention for positives” (PfP) interventions.

Recent Findings

Early work on prevention for positives focused on understanding the dynamics of risky behavior among People Living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH) and on designing, implementing, and evaluating a limited number of interventions to promote safer sexual and drug use behavior in this population (i.e., PfP interventions). Previous meta- analyses demonstrated that PfP interventions can effectively promote safer behavior. However, the understanding of risk dynamics among PLWH, and the extant number and breadth of effective PfP interventions, were scant. Recent work has addressed some of these problems, yielding greater understanding of risk dynamics and providing additional, effective, interventions. Still, only a modest number of recent, rigorously evaluated, effective interventions have been identified. New ideas for creating stronger, more integrated, and effective PfP interventions have emerged which will guide future intervention research and practice.

Summary

There remains much to be done to understand why, when, and under what conditions PLWH practice risk. Substantial work also needs to be performed to design, implement, rigorously evaluate, and when effective, to disseminate widely, additional, evidence-based, PfP interventions targeting diverse populations. Directing such interventions to populations of PLWH at greatest risk for transmission of HIV has the potential to yield significant impact on the pandemic.

Keywords: Secondary prevention of HIV, Prevention for Positives interventions, HIV prevention, People Living with HIV (PLWH)

Introduction

Approaches to HIV prevention have typically focused on individuals who are HIV seronegative or whose serostatus is unknown (1). Nevertheless, all HIV infections originate with a seropositive individual, and about one -third of seropositives who know their status continue to practice risky sexual or drug use behavior (2–6). Moreover, since the advent of antiretrovirals (ARVs), seropositives are thankfully living longer, healthier lives. Yet if they practice risky behavior, they have the potential to contract other pathogens and to infect others with HIV, even resistant strains of the virus, over extended periods. In the past ten years, the US CDC and international organizations (e.g., UNAIDS) have stated that a complete approach to HIV prevention must focus on both seronegatives and seropositives (7–9). We review recent research on the dynamics of HIV risk behavior among PLWH, and on interventions that have been specifically designed to lower levels of risk among PLWH.

Overview

At present, there are about 33.2 million PLWH worldwide (8). Sub-Saharan African has been disproportionately impacted by HIV. There, HIV is primarily transmitted through unprotected heterosexual sex in the general population and accounts for 22.5 million of all PLWH worldwide and 1.7 of the 2.5 million new infections in 2007. The epidemic in the rest of the world is concentrated among men who have sex with men (MSM), intravenous drug users (IDU), sex workers, and their partners (8).

Given the large number of PLWH worldwide, PfP, which can target diverse preventive behaviors (e.g., safer sexual behaviors, safer needle drug use behaviors), has great potential to impact the epidemic by leading to behavior change among PLWH who know their serostatus. The percentage of PLWH who know their antibody status varies worldwide, and is greater in developed than undeveloped nations (10,11). Many PLWH respond to the knowledge they are seropositive, gained from HIV testing, by practicing safer behavior. In a meta-analysis, it was concluded that for PLWH who know their serostatus, rates of unprotected sex with partners of negative or unknown status is reduced by sixty-eight percent (12). However, periods during which PLWH abstain from or engage in risk fluctuate over time (13–15). For those who engage in risky behavior, secondary prevention interventions often encourage more traditional prevention strategies (e.g., consistent condom use, reducing partners, abstinence, serostatus disclosure, and clean injection equipment) to reduce transmission. Harm reduction strategies such as negotiating condom use with specific types of partners (e.g., anonymous partners) (16), sexual positioning to reduce the time and area of mucosal membranes exposed to infection (e.g., a male seropositive partner assuming the receptive role in anal intercourse) (17), and serosorting (e.g., limiting sexual intercourse to persons of similar perceived status) (17); are less effective in reducing risk. However, when offered as part of a combination of strategies (e.g., with consistent condom use outside of the primary relationship), they may help PLWH achieve risk reduction when more traditional strategies fail. To be effective, prevention strategies must be targeted toward contexts in which PLWH are less likely to initiate or maintain safer behavior, acknowledging that risk dynamics vary among subpopulations of PLWH (e.g., women, MSM, IDU). Recently, biomedical risk reduction approaches involving adherence to ARVs (to lower viral load) (18, 19) have added a promising HIV prevention component.

Risk Dynamics

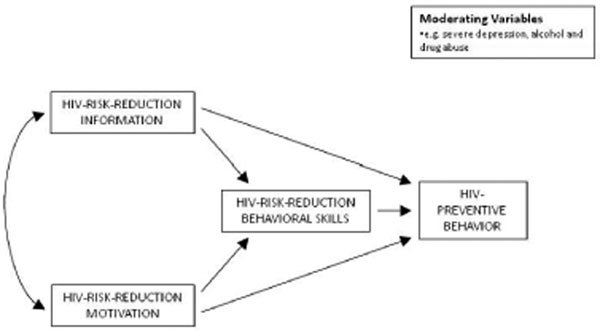

We view the factors which influence risky behavior among PLWH consistent with the well-validated Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) model of HIV preventive behavior (20, 21). In terms of the model (see figure 1), a PLWH's level of HIV prevention-relevant information, motivation, and behavioral skills determine his or her level of risky or safer behavior. Specifically, when an individual is informed about HIV transmission and prevention and motivated to practice preventive behavior, they enact critical skilled behaviors, which result in the practice of HIV preventive behavior per se. Deficits, or weaknesses, in information, motivation and/or behavioral skills result in risky behavior. Interventions targeting PLWH which address deficits in IMB model elements will generally increase levels of safer behavior. The efficacy of such interventions may be affected by moderating variables (e.g., severe depression, alcohol and drug abuse). While the IMB model and model-based interventions are robust with respect to these variables, at extreme levels these conditions must be addressed independently (e.g., through separate interventions to eliminate or reduce alcohol or drug consumption), for IMB model-based HIV prevention interventions to be maximally effective.

Figure 1.

Three fundamental determinant of HIV-risk and preventive behavior among seropositives. After Fisher, J.D. & Fisher, W.A. (1992). Changing AIDS-Rish Behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 111, 455–474.

Information necessary for PLWH to practice prevention involves knowledge about HIV transmission and prevention (e.g., knowing that condoms and abstinence prevent HIV transmission (22), knowledge of contraception and safe reproductive planning (23,24), and not possessing incorrect information (e.g., myths that being on ARVs invariably prevents transmission; believing that how a partner “looks” indicates their serostatus, (25), or that risky behavior with other PLWH is “safe” (26).

Motivation to practice prevention involves having favorable attitudes toward practicing specific PfP behaviors (e.g., condom use, disclosing one’s serostatus, adhering to ARVs, etc.) and perceiving social normative support from important others, such as one's sexual partners or family, for these actions. Behavioral skills for prevention involve the ability to keep condoms on hand and to use them, even in the face of countervailing elements (e.g., partners who do not want to use condoms, being under the influence of drugs or alcohol, etc.). Critical behavioral skills also involve the ability to negotiate safer sex, to leave unsafe situations, to substitute safer for risky behavior, to disclose one's status, and to adhere to ARVs, among others.

Consistent with the IMB model, past work on risk dynamics among PLWH has indeed found that individuals’ levels of HIV prevention information, motivation, and behavioral skills are associated with levels of risky and preventive behavior (4,27,28). For information, recent studies have further demonstrated the importance that knowledge of HIV transmission risk plays in lowering risk-taking behavior across diverse samples of PLWH (23,24,26,29–32).

With respect to motivation, past studies have shown that pro-prevention attitudes and social norms among PLWH are associated with preventive behavior (4,27,33). In more recent work, perceived responsibility and motivation to protect one’s self and one’s partners predict increased safer behavior among PLWH (32,34–36). Further, supportive peer norms facilitate safer injection behaviors among seropositive IDUs (37,38). Fertility desires (23,31,39,40), cultural taboos (30,41), and stigma (29,42*,43) surrounding sexual activity and same-sex behaviors (44,45) decrease risk reduction motivation.

With respect to behavioral skills, skills for consistent condom use, safer sex negotiation, and disclosure help PLWH to reduce risk (4,27,46–48). In our own work with PLWH, we consistently find, across studies, a relation between self-reports of risk reduction behavioral skills and practicing lower levels of risky behavior (Amico, KR, personal communication). Recent work demonstrates that skills for not sharing injection drug paraphernalia lower risk behavior in PLWH who are IDUs (37). Sexual risk reduction among PLWH may also be achieved by increasing skills to reduce alcohol consumed prior to intercourse (49), and enhancing skills that facilitate safer sex discourse and disclosure of antibody status (22,49).

Concerning moderators, or factors that will affect the relationship of PLWH’s levels of information, motivation, and behavioral skills, with their levels of safer or risky behavior, research continues to identify factors such as extreme poverty (50), housing instability (13,51), intimate partner violence (52), mental health concerns (37,38,42*,53,54), and substance use (49,55,56) which may need to be targeted prior to, or concurrent with, addressing risk reduction behavior change in behavioral interventions. By addressing relevant moderating factors, barriers to behavior change can be reduced. Treatment of severe addiction and mental illness may also improve one’s capacity to attend to behavioral interventions.

Early PfP Interventions

For many years, the focus of HIV prevention interventions was those presumed to be seronegative. Beginning with the second decade of the epidemic, this focus was urgently expanded to PLWH (57). The overall goals of PfP interventions are to prevent HIV transmission to others, and to ensure optimal health in PLWH (7). Many PfP interventions focus on safer behavior, which prevents HIV transmission to others and keeps PLWH from acquiring additional pathogens. To date, relatively few PfP interventions have had a joint focus on preventing risk and enhancing ARV adherence. This can affect both infectivity and transmission of resistant HIV strains, and also safeguard health of PLWH. Thus far, very few PfP interventions have focused broadly on improving seropositives’ health.

Initially, two intervention models emerged to reduce HIV transmission by PLWH (47). One employed the same HIV prevention strategies used with populations at-risk for HIV (e.g., HIV testing and counseling). This reduced risk in many PLWH, especially those with serodiscordant partners, but failed to effectively change or maintain safer behavior for others (12,14,27,47). The limitation of this model was likely that it involved a “one time” intervention during a period of acute anxiety and also failed to address relevant information, motivation, or behavioral skills factors specifically relevant to reducing risk in the context of living with HIV (4,6,20,21,47). More recent models for PfP interventions have stressed understanding and addressing the dynamics of risky behavior for PLWH and integrating HIV prevention with other care and support services (4,12).

Despite the relatively recent emphasis on PfP (1), prior to 2006, there were several individual- and group-level PfP interventions which yielded mixed results (57–65). This suggested that successful PfP interventions may demand information, motivation, and behavioral skills content (48) and other elements (e.g., substance abuse and mental health services), to address complex dynamics of living with HIV which were not incorporated in some early interventions. It also indicated a need to expand traditional prevention messages of “consistent condom use with all partners, for all sexual behaviors” (4,6) and explore additional prevention objectives (e.g., concurrent HIV testing, safer sex with secondary partners) which may prove to be more practical, though less effective, intervention strategies for some PLWH (4).

Two meta-analyses (66,67) have emerged which demonstrate the overall potential for efficacy of PfP interventions, including those reviewed above, when taken as a whole. These meta-analyses also highlight the conditions under which PfP interventions are most likely to be effective. Each reviews interventions published primarily through 2004 and while they are very helpful, given the increasing emphasis on PfP interventions, a newer, updated meta-analysis would be welcome as new studies accumulate.

Crepaz et al. (66) reviewed twelve pre-2004 PfP intervention trials meeting stringent criteria, many including information, motivation, and behavioral skills (IMB) intervention components, and reported that this body of research, overall, greatly reduced PLWH’s levels of unsafe sex, decreased STIs, and would likely be cost-effective in terms of health outcomes (66). Unfortunately, intervention effects on needle-sharing were non-significant. Over the sample of interventions, those which were most effective had the following characteristics: they used behavioral theory, were targeted to change HIV transmission risk behaviors, were given either by health care providers or counselors, were intensive, and were delivered over a period of more than three months at the individual-level, and at sites where PLWH receive medical care and other services. The most effective interventions also included a skills building component, and addressed one or more issues related to HIV risk behavior, medication adherence, or mental health.

The Johnson et al. (67) meta-analysis revealed similar results. Data from 15 trials meeting stringent criteria were reviewed, and again, PfP interventions reduced risk with respect to unsafe sex, compared to control conditions. Interventions did not reduce reported number of sex partners. In this meta-analysis and in Crepaz et al. (66), the effect sizes for condom use were equal to or stronger than in earlier meta-analyses of HIV prevention interventions for HIV-negative populations. In Johnson et al.’s (67) meta-analysis, interventions were most successful at improving condom use if the sample included lower numbers of MSM, or participants who were younger. Interventions with information, motivation and behavioral skills components were more effective overall. Since none of the interventions included in the meta-analysis targeting seropositive MSM had all the requisite IMB components, future research must ascertain if such interventions would, as expected (68) be effective.

More Recent work on PfP Interventions

An extensive literature review of recent PfP interventions identified a reasonable number of newer studies. Of these, many involved descriptions of interventions that had been designed and implemented but not evaluated for outcomes (69–76). We also found a number of recent PfP interventions which involved rigorous intervention outcome studies. Most were interventions to increase safer sexual and drug use behaviors, which also protect PLWH from other pathogens. A number involved secondary prevention with respect to other health outcomes (e.g., interventions to favorably impact mental health and immune functioning) relevant to PLWH. We will discuss recent interventions to decrease risky sexual and drug use risk behavior in PLWHA below.

Recall that Crepaz et al. (66) suggested that PfP interventions situated in health care settings were especially effective. Two studies published recently by J. Fisher and associates (15,77) focused on linking HIV prevention with clinical care for PLWHA. In work performed in the US (15), researchers taught physicians how to have IMB model-based “conversations about prevention” with seropositive patients, using Motivational Interviewing (MI) for intervention delivery (78). Intervention recipients decreased risk behavior over time; those receiving the standard-of-care with respect to prevention actually increased risk, highlighting the cost of doing nothing. Cornman et al. (77) then adapted these clinic-based procedures to the health care system and the HIV risk dynamics in South Africa, and in an intervention delivered by HIV counselors rather than physicians (due to cost considerations and scarcity of physicians), reported similar outcomes.

Another intervention tested in outpatient clinics (79*) involved “Positive Choice”, an interactive software program designed to perform a risk assessment and provide tailored risk reduction counseling for PLWH, based on MI. It framed behavior change for PLWH more to protect the patient’s own health than to protect others, a strategy suggested in some recent PfP commentaries (80). Patients reporting risk behavior were randomly assigned to the intervention, including a “video doctor,” or to a control condition. The former led to less risk behavior involving illicit drugs and less unprotected sex than the control condition.

In Uganda, Bonell et al. (81) assessed the secondary prevention effects of ARV initiation coupled with a behavioral intervention involving sexual risk behavior counseling and free condoms. Overall, the intervention reduced sexual risk behavior by 70% over six months. While there was no control condition, these findings suggest the potential of linking prevention with African ARV rollouts. Note that intervention participants appear to have decreased risk behavior even though they indicated increasing sexual desire and having more opportunities to meet new partners after initiating ARV s.

Jones et al. (82) randomly assigned seropositive Zambian women attending a hospital clinic to a group- or individually-based intervention; there was no control condition. The group-based condition included 3 sessions with a focus on group cohesion, skills building and practice, and experimentation and feedback on sexual barrier products. The individual-level intervention offered information in a standard health education format, skills training and access to videos and written materials. Sexually active individuals used sexual barriers and male condoms more in the group-than in the individual-condition. There were no between-condition differences for use of female condoms, lubricants alone (to counter dry sex), or lubricants with condoms, all of which increased in both conditions.

Several recent PfP interventions have been performed outside of clinical care settings. For example, Lightfoot et al. (76) adapted a successful community-based PfP intervention initially implemented with US youth to Ugandan youth living with HIV. Participants were randomly assigned to an intervention or control condition. Youth in the intervention used condoms and decreased number of sexual partners more than controls. Based on studies which showed that PLWHA with childhood sexual abuse engage in more risk behavior (28,83,84), Sikkema and colleagues (84)created a coping-based intervention to lower their risk. It involved 15-sessions, and the control condition was a therapeutic support group. Intervention participants reduced unsafe sex more than controls for up to 12 months.

Recent interventions have attempted to lower risk behavior among drug using PLWH. The INSPIRE study (85) recruited seropositive IDU in four cities and randomly assigned them to a ten-session intervention involving peer mentoring, or to a control condition consisting of a video-based discussion intervention. Both conditions reduced injection risk and sexual risk behavior compared to baseline, but the intervention condition was not differentially effective (85,86). The EDGE study (87) randomly assigned PLWH with ongoing methamphetamine use to a safer sex intervention, or to a time- matched diet and exercise intervention. EDGE participants practiced greater safer behavior at 8- and 12-month intervals. Margolin et al. (88) employed more unorthodox intervention methods to reduce impulsivity in drug using PLWH. Individuals were randomly assigned to a “spiritual self-schema therapy” intervention (which integrates cognitive and Buddhist psychologies for increasing safer behaviors) or to a standard-of-care control condition. Those in the intervention decreased impulsivity and drug use, and exhibited more motivation for abstinence, HIV prevention, and medication adherence.

Another large trial, the Healthy Living Project (89) involved recruiting risky PLWH from four groups (IDU, MSM, primarily heterosexual men, and women), in four cities. Fifteen PfP sessions were administered in the intervention group; there was also a wait-list control group. Risky behavior was lowered in the intervention group over intervals from 5 to 20 months, with the largest reduction at 20 months. All of these differences disappeared by the 25 month follow-up, perhaps demonstrating the need for booster sessions.

The future of PfP interventions

Extant PfP interventions have generally been “stand alone” projects in which PLWH have been recruited for interventions that focus on reducing risky practices. Future PfP interventions should be broader in their objectives than a narrow focus on safer behaviors per se, broader in the populations targeted, and substantially more integrated into an array of medical, social, psychological, and other services which PLWH may need. In effect, we need to recognize the role of a spectrum of services in facilitating PfP. Further, we must seriously consider designing and integrating PfP interventions so they have the potential to continue, when needed, at each medical visit, rather than ending precipitously, as most PfP interventions do (for exceptions, see (15,77)). When PfP (and other HIV prevention interventions) end, the effects tend to decay (89), yet PfP must be a lifetime enterprise. Many elaborations on these themes, which follow below, are discussed in detail in excellent papers by Temoshok and Wald (90), Remien et al. (91**), and others (92**).

To cast the widest possible net, future PfP interventions should include early identification of PLWH through broad-based HIV testing initiatives, especially within “high risk” populations (93). Outreach could include targeting individuals who practice high risk behaviors, their social networks, those with diseases with pathways to infection similar to HIV, patients in STI clinics, young women attending antenatal clinics, and others. “Opt out” testing could be incorporated in medical facilities offering routine and emergency care (93). When individuals are tested and have access to treatments earlier, they are prescribed ARVs and have lowered viral loads and decreased infectivity earlier, can be exposed to PfP interventions earlier, and have opportunities to improve their health and protect others (90,91**). The act of being identified as HIV -infected leads to safer behavior (12), safety which is likely augmented biologically by ARVs. When individuals are not identified early, they may practice risk during periods of high infectivity, and opportunities for promoting their own and others’ health are missed (e.g., delivering behavioral and biomedical interventions to reduce horizontal and vertical transmission) (90,91**).

In addition to casting a wider net for targets for intervention, future interventions must address other pressing psychosocial needs of PLWH (e.g., substance use, mental health and reproductive health needs) more aggressively, through referral and vigorous follow-up. For example, PfP programs must be directly linked with alcohol and drug treatment programs, since alcohol and drug use increase risk behavior among PLWH (56,94,95). Pregnancy desires of women and their partners, which are also associated with risky sex among PLWH, contribute to both horizontal and vertical HIV transmission (91**), and have not been well addressed in past PfP interventions, or by some reproductive health service providers (96). Inclusion of relevant content in interventions, as well as referrals to reproductive health professionals can result in relatively safer techniques for achieving pregnancies (e.g., only having unprotected sex at times of highest fertility, adhering to ARVs, cesarean delivery) (96). For PLWH who do not want to become pregnant, barrier methods can prevent pregnancy and HIV transmission. In addition to linking PLWH with care, next generation PfP programs must help keep individuals in care since this enhances general health and PfP-relevant outcomes (97,98). Those who remain in care can access PfP programs, have their ARVs monitored, their adherence enhanced, be checked for viral load and resistance, and be treated for co-morbid conditions.

PfP programs must also provide effective referrals for homelessness and financial emergencies, for gender and other violence, provide access to clean needles (where possible), to male and female condoms, and to other, critical services. For many PLWH, HIV is part of a syndemic (i.e., the interplay of multiple social and health problems that mutually facilitate risk for negative outcomes) (99), which must be addressed using multiple intervention methods. Many of these syndemic conditions (e.g., co-occurring alcohol and drug use, extreme poverty, homelessness, and violence) have been shown, independently, to produce risk behavior. This suggests that for PfP to be optimally effective, we must integrate PfP with care, treatment, and other critical ancillary services in a “treatment cocktail” and must exploit all potential synergies (90,91**). This may involve individuals with different specialties working together, referring to each other, or even cross-training and possessing knowledge of each other’s specialties.

In this vein, consider a nonadherent patient on ARVs who is practicing risky sexual and IDU behavior. An optimally effective PfP intervention for this PLWH—or any PLWH, must address any behavioral (e.g., risky sex, drug use, nonadherence) or biological element (e.g., inadequate ARV regimen, co morbid conditions), or their interaction, which may affect infectivity to others (e.g., viral load and/or viral resistance). Behavior and biology interface in critical ways. For example, often, risky behavior and nonadherence to ARVs, with its biologic consequences, co-occur. Those likely to have resistant virus may be especially apt to practice risky behavior (91**,100). Addressing these issues from only a behavioral or biological perspective is insufficient; a synergistic approach with input across specialties is critical. Such integration may be easier when prevention occurs in a clinical setting. Effective PfP needs to include behavioral approaches to reduce risk, medical approaches to deal with drug resistance and infectivity and, on occasion, mental health, addiction, and other interventions.

To have the most significant effect on the epidemic, future PfP programs need to target populations in greatest need. Since 70 percent of new HIV infections occur in Sub Saharan Africa (91**), this region is a critical focus. The ARV rollout there will reduce stigma, increase HIV testing, and bring people into care where they can be exposed to PfP interventions (15,101). As we noted earlier, special attempts should also be made worldwide to target PfP programs to PLWH with high HIV infectivity (92**). It may also be critical to target PfP to those new to ARVs, who may become more risky as they feel better. Further, PLWH who are refractory to brief interventions, and who have characteristics which make them especially likely to practice risk behavior, should be triaged to more intensive PfP. All such interventions should include behavioral and biomedical components.

Finally, few extant PfP interventions have been widely disseminated, without which it is impossible for them to impact the epidemic (102). It is unclear whether interventions developed and tested predominantly in resource-rich environments with particular HIV risk dynamics and health care systems, will work in different contexts (91**). Note however, that several PfP interventions developed in the U.S. were modified, tested, and found to work in Africa (76,77). One of these involved using lower cost intervention personnel (e.g., HIV counselors, rather than physicians [76]), an adaptation needed when disseminating interventions to resource poor settings. Kalichman et al. (103) showed that other significant changes may be made in PfP intervention protocols, possibly without affecting outcomes. Note also that widespread dissemination of PfP will necessitate critical organizational-level interventions (e.g., to counteract negative attitudes toward PfP interventions, or staff feelings of inefficacy to change behavior of PLWH) (104), and will also need to promote integration of PfP across levels of health care organizations in order to integrate PfP and medical services (90,91**).

Conclusion

Extant work on PfP has addressed both the dynamics of risk and the reduction of risk-related behaviors among PLWH. In light of this review, future PfP work that aims to integrate both behaviorally and biologically based prevention is likely to yield a more substantial impact on the current pandemic. As life circumstances and subsequent risk dynamics evolve throughout an individual life span, PfP messages and support must be adapted to meet this variation in context within resource constrained settings and across different sub-populations of PLWH. Thus, future work on PfP must consider systematically performing positive prevention across a continuum of social and care services in order to improve both the overall health of PLWH and help to address other risk-related factors (e.g., fertility desires, mental illness, substance use).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank William Fisher for his comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. We also wish to acknowledge the support of NIMH grant RO1 MH077524, which facilitated work on this manuscript

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey D. Fisher, University of Connecticut, Director, Center for Health, Intervention, and Prevention (CHIP), Professor, Department of Psychology, 2006 Hillside Road, Unit 1248, Storrs, CT 06269-1248, Phone: 860-208-4393, Jeffrey.fisher@uconn.edu.

Laramie Smith, University of Connecticut, Graduate Student, Department of Psychology, Center for Health, Intervention, and Prevention, 2006 Hillside Road, Unit 1248, Storrs, CT 06269-1248, Phone: 860-486-2313, laramie.smith@uconn.edu.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Fisher WA, Kohut T, Fisher JD. AIDS Exceptionalism? On the Social Psychology of HIV Prevention Research. Social Issues and Policy Review. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2409.2009.01010.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marks G, Burris S, Peterman TA. Reducing sexual transmission of HIV from those who know they are infected: the need for personal and collective responsibility. AIDS. 1999;13(3):297–306. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199902250-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metsch LR, McCoy CB, Lai S, Miles C. Continuing risk behaviors among HIV-seropositive chronic drug users in Miami, Florida. AIDS and Behavior. 1998;2:161–169. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crepaz N, Marks G. Towards an understanding of sexual risk behavior in people living with HIV: a review of social, psychological, and medical findings. AIDS. 2002;16:135–149. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalichman SC.Psychological and social correlates of high-risk sexual behaviour among men and women living with HIV/AIDS AIDS Care 199908;114415–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly JA, Kalichman SC. Behavioral research in HIV/AIDS primary and secondary prevention: Recent advances and future directions. J.Consult.Clin.Psychol. 2002;70(3):626–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janssen RS, Holtgrave DR, Valdiserri RO, Shepherd M, Gayle HD, De Cock KM. The Serostatus Approach to Fighting the HIV Epidemic: Prevention Strategies for Infected Individuals. Am.J.Public Health. 2001;91(7; 7):1019–1024. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UNAIDS. [Accessed 01/19, 2009];AIDS epidemic update: December 2007. 2007 Available at: http://data.unaids.org/pub/EPISlides/2007/2007_epiupdate_en.pdf.

- 9.UNAIDS. [Accessed 01/19, 2009];Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly. 2006 Available at: http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2006/20060615_HLM_PoliticalDeclaration_ARES60262_en.pdf.

- 10.Marks G, Crepaz N, Janssen RS. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. AIDS. 2006;20(10):1447–1450. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000233579.79714.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF. [Accessed March 28, 2009];Towards Universal Access: Scaling-up Priority HIV/AIDS Interventions in Health Sector Progress Report. 2008 Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/towards_universal_access_report_2008.pdf.

- 12.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;39(4):446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aidala AA, Lee G, Garbers S, Chiasson MA. Sexual behaviors and sexual risk in a prospective cohort of HIV-positive men and women in New York City, 1994–2002: Implications for prevention. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(1):12–32. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinhardt L. HIV Diagnosis and Risk Behavior. In: Kalichman SC, editor. Positive Prevention: Reducing HIV Transmission among People Living with HIV/AIDS. New York: Kluwer Acidemic/Plenum Publishers; 2005. pp. 29–63. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Cornman DH, Amico RK, Bryan A, Friedland GH. Clinician-delivered intervention during routine clinical care reduces unprotected sexual behavior among HIV-infected patients. JAIDS. 2006;41(1):44–52. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000192000.15777.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. Partner type and sexual risk behavior among HIV positive gay and bisexual men: social cognitive correlates. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12(4):340–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parsons JT, Schrimshaw EW, Wolitski RJ, Halkitis PN, Purcell DW, Hoff CC, Gómez CA. Sexual harm reduction practices of HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men: serosorting, strategic positioning, and withdrawal before ejaculation. AIDS. 2005;19 Suppl 1:S13–S25. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000167348.15750.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porco TC, Martin JN, Page-Shafer KA, Cheng A, Charlebois E, Grant RM, Osmond DH. Decline in HIV infectivity following the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2004;18(1):81–88. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000096872.36052.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flaks RC, Burman WJ, Gourley PJ, Rietmeijer CA, Cohn DL. HIV transmission risk behavior and its relation to antiretroviral treatment adherence. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2003;30(5):399–404. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200305000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychol.Bull. 1992;111(3):455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Theoretical approaches to individual-level change. In: Peterson J, DiClemente R, editors. HIV Prevention Handbook. New York: Kluwer Acidemic/Plenum Publishers; 2000. pp. 3–55. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dave SS, Stephenson J, Mercey DE, Panahmand N, Jungmann E. Sexual behaviour, condom use, and disclosure of HIV status in HIV infected heterosexual individuals attending an inner London HIV clinic. Sex.Transm.Infect. 2006 April 1;82(2):117–119. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.015396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bakeera-Kitaka S, Nabukeera-Barungi N, Nöstlinger C, Addy K, Colebunders R. Sexual risk reduction needs of adolescents living with HIV in a clinical care setting. AIDS Care. 2008;20(4):426–433. doi: 10.1080/09540120701867099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castro A, Khawja Y, González-Núñez I. Sexuality, reproduction, and HIV in women: the impact of antiretroviral therapy in elective pregnancies in Cuba. AIDS. 2007;21 Suppl 5:S49–S54. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000298103.02356.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong DS, Goldstein RB, Borus MJ, Wong FL, Gore-Felton C. Perceived partner serostatus, attribution of responsibility for prevention of HIV transmission, and sexual risk behavior with "MAIN" partner among adults living with HIV. AIDS Educ.Prev. 2006;18(2):150–162. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poudel KC, Nakahara S, Poudel-Tandukar K, Jimba M. Perceptions towards preventive behaviours against HIV transmission among people living with HIV/AIDS in Kathmandu, Nepal. Public Health. 2007;121(12):958–961. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reilly T, Woo G. Predictors of high-risk sexual behavior among People Living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2001;5(3):205–217. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalichman SC, Sikkema KJ, DiFonzo K, Luke W, Austin J. Emotional Adjustment in Survivors of Sexual Assault Living with HIV-AIDS. J.Trauma.Stress. 2002;15(4; 4):289. doi: 10.1023/A:1016247727498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernet M, Proulx-Boucher K, Richard M, Lévy JJ, Otis J, Samson J, et al. Issues of sexuality and prevention among adolescents living with HIV/AIDS since birth. Can.J.Hum.Sex. 2007;16(3):101–111. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chakrapani V, Newman PA, Shunmugam M. Secondary HIV prevention among kothi-identified MSM in Chennai, India. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2008;10(4):313–327. doi: 10.1080/13691050701816714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakayiwa S, Abang B, Packel L, Lifshay J, Purcell DW, King R, et al. Desire for children and pregnancy risk behavior among HIV-infected men and women in Uganda. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10:S95–s104. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Latka MH, Mizuno Y, Wu Y, Tobin KE, Metsch LR, Frye V, et al. Are feelings of responsibility to limit the sexual transmission of HIV associated with safer sex among HIV-positive injection drug users? JAIDS. 2007;46(2):S88–s95. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815767b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly JA, Hoffman RG, Rompa D, Gray M. Protease inhibitor combination therapies and perceptions of gay men regarding AIDS severity and the need to maintain safer sex. AIDS. 1998;12(10):F91–F95. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199810000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inoue Y, Yamazaki Y, Kihara M, Wakabayashi C, Seki Y, Ichikawa S. The Intent and Practice of Condom Use Among HIV-Positive Men Who Have Sex with Men in Japan. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20(11):792–802. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sri Krishnan AK, Hendriksen E, Vallabhaneni S, Johnson SL, Raminani S, Kumarasamy N, et al. Sexual behaviors of individuals with HIV living in South India: A qualitative study. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2007;19(4):334–345. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fisher HH, Purcell DW, Hoff CC, Parsons JT, O'Leary A. Recruitment Source and Behavioral Risk Patterns of HIV-Positive Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(5):553–561. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Metsch LR, Pereyra M, Purcell DW, Latkin CA, Malow R, Gómez CA, et al. Correlates of lending needles/syringes among HIV-seropositive injection drug users. JAIDS. 2007;46 Suppl 2:572–579. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181576818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Latkin CA, Buchanan AS, Metsch LR, Knight K, Latka MH, Mizuno Y, et al. Predictors of Sharing Injection Equipment by HIV-Seropositive Injection Drug Users. JAIDS. 2008;49(4):447–450. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e31818a6546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanniappan S, Jeyapaul MJ, Kalyanwala S. Desire for motherhood: Exploring HIV-positive women's desires, intentions and decision-making in attaining motherhood. AIDS Care. 2008;20(6):625–630. doi: 10.1080/09540120701660361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore AR, Oppong J. Sexual risk behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS in Togo. Soc.Sci.Med. 2007;64(5):1057–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Venkatesh KK, Prasad L, Mayer KH, Kumarasamy N. HIV transmission transcends three generations: can we prevent secondary transmission in India? International journal of STD & AIDS. 2008;19:418–420. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Whetten K, Reif S, Whetten R, Murphy-McMillan LK. Trauma, Mental Health, Distrust, and Stigma Among HIV-Positive Persons: Implications for Effective Care. Psychosom.Med. 2008 June 1;70(5):531–538. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817749dc. *This report reviews the prevalence of poorer mental health status, stigma and limited trust in the health care system across PLWH both globally and domestically; their impact on HIV-related risk and adherence behaviors and need for co-occurring intervention work.

- 43.Illa L, Brickman A, Saint-Jean G, Echenique M, Metsch L, Eisdorfer C, et al. Sexual risk behaviors in late middle age and older HIV seropositive adults. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12(6):935–942. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Leary A, Fisher HH, Purcell DW, Spikes PS, Gomez CA. Correlates of risk patterns and race/ethnicity among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11(5):706–715. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson MO, Carrico AW, Chesney MA, Morin SF. Internalized heterosexism among HIV-positive, gay-identified men: Implications for HIV prevention and care. J.Consult.Clin.Psychol. 2008;76(5):829–839. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.5.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chesney MA, Folkman S, Chambers D. Coping effectiveness training for men living with HIV: preliminary findings. International journal of STD & AIDS. 1996;7 Suppl 2:75–82. doi: 10.1258/0956462961917690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalichman SC. HIV Transmission Risk Behaviors of Men and Women Living With HIV-AIDS: Prevalence, predictors, and emerging clinical interventions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Preactice. 2000;7(1):32–47. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carey MP, Lewis BP. Motivational Strategies Can Augment HIV-Risk Reduction Programs. AIDS and Behavior. 1999;3(4):269–276. doi: 10.1023/a:1025429216459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.King R, Katuntu D, Lifshay J, Packel L, Batamwita R, Nakayiwa S, et al. Processes and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among people living with HIV in Uganda. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12(2):232–243. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9307-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fawzi MCS, Jagannathan P, Cabral J, Banares R, Salazar J, Farmer P, et al. Limitations in knowledge of HIV transmission among HIV-positive patients accessing case management services in a resource-poor setting. AIDS Care. 2006;18(7):764–771. doi: 10.1080/09540120500373844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leaver CA, Bargh G, Dunn JR, Hwang SW. The effects of housing status on health-related outcomes in people living with HIV: A systematic review of the literature. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:S85–s100. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9246-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Henny KD, Kidder DP, Stall R, Wolitski RJ. Physical and sexual abuse among homeless and unstably housed adults living with HIV: prevalence and associated risks. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11(6):842–853. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9251-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bouhnik A, Préau M, Schiltz M, Peretti-Watel P, Obadia Y, Lert F, et al. Unsafe Sex With Casual Partners and Quality of Life Among HIV-Infected Gay Men: Evidence From a Large Representative Sample of Outpatients Attending French Hospitals (ANRS-EN12-VESPA) JAIDS J.Acquired Immune Defic.Syndromes. 2006;42(5):597–603. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000221674.76327.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schackman BR, Dastur Z, Ni Q, Callahan MA, Berger J, Rubin DS. Sexually active HIV-positive patients frequently report never using condoms in audio computer-assisted self-interviews conducted at routine clinical visits. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(2):123–129. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barta WD, Portnoy DB, Kiene SM, Tennen H, Abu-Hasaballah KS, Ferrer R. A daily process investigation of alcohol-involved sexual risk behavior among economically disadvantaged problem drinkers living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12(5):729–740. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9342-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bryant KJ. Expanding Research on the Role of Alcohol Consumption and Related Risks in the Prevention and Treatment of HIV/AIDS; Subst. Use Misuse. 2006;41:1465–1507. doi: 10.1080/10826080600846250. 10–12; 10–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wolitski RJ, Gómez CA, Parsons JT. Effects of a peer-led behavioral intervention to reduce HIV transmission and promote serostatus disclosure among HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men. AIDS. 2005;19 Suppl 1:S99–S109. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000167356.94664.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cleary PD, Van Devanter N, Steilen M, Stuart A, Shipton-Levy R, McMullen W, et al. A randomized trial of an education and support program for HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 1995;9(11):1271–1278. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199511000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grinstead O, Zack B, Faigeles B. Reducing postrelease risk behavior among HIV seropositive prison inmates: the health promotion program. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2001;13(2):109–119. doi: 10.1521/aeap.13.2.109.19737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M, DiFonzo K, Simpson D, Austin J, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce HIV transmission risks in HIV-positive people. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;21(2):84–92. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Bahr GR, Kalichman SC, Morgan MG, Stevenson LY, et al. Outcome of cognitive-behavioral and support group brief therapies for depressed, HIV-infected persons. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150(11):1679–1686. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.11.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Patterson TL, Shaw WS, Semple SJ. Reducing the Sexual Risk Behavior of HIV+ Individuals: Outcome of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;25(2; 2):137. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2502_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Richardson JL, Milam J, McCutchan A, Stoyanoff S, Bolan R, Weiss J, et al. Effect of brief safer-sex counseling by medical providers to HIV-1 seropositive patients: a multi-clinic assessment. AIDS. 2004;18(8):1179–1186. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200405210-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lee MB, Murphy DA, Futterman D, Duan N, Birnbaum JM, et al. Efficacy of a Preventive Intervention for Youths Living With HIV. Am.J.Public Health. 2001;91(3; 3):400–405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Comulada WS, Weiss RE, Lee M, Lightfoot M. Prevention for substance-using HIV-positive young people: telephone and in-person delivery. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;37 Suppl 2:S68–S77. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140604.57478.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Wolitski RJ, Passin WF, Rama SM, Herbst JH, et al. Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviours among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trials. AIDS. 2006;20(2):143–157. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196166.48518.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Johnson BT, Carey MP, Chaudoir SR, Reid AE. Sexual risk reduction for persons living with HIV: research synthesis of randomized controlled trials, 1993 to 2004. JAIDS. 2006;41(5):642–650. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000194495.15309.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Shuper PA. The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model of HIV Preventive Behavior. In: DiClemente R, Crosby R, Kegler M, editors. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Publishers; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Estrada BD, Trujillo S, Estrada AL. Supporting healthy alternatives through patient education: A theoretically driven HIV prevention intervention for persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:S95–s105. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen FH. On the transmission of HIV with self-protective behavior and preferred mixing. Mathematical Biosciences. 2006;199(2):141–159. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Golin CE, Patel S, Tiller K, Quinlivan EB, Grodensky CA, Boland M. Start talking about risks: Development of a motivational interviewing-based safer sex program for people living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:S72–s83. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9256-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grimley DM, Bachmann LH, Jenckes MW, Erbelding EJ. Provider-delivered, theory-based, individualized prevention interventions for HIV positive adults receiving HIV comprehensive care. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:S39–s47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Raja S, McKirnan D, Glick N. The treatment advocacy program-Sinai: A peer-based HIV prevention intervention for working with African American HIV-infected persons. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:S127–s137. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Teti M, Rubinstein S, Lloyd L, Aaron E, Merron-Brainerd J, Spencer S, et al. The protect and respect program: A sexual risk reduction intervention for women living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:S106–s116. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9275-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Knauz RO, Safren SA, O'Cleirigh C, Capistrant BD, Driskell JR, Aguilar D, et al. Developing an HIV-prevention intervention for HIV-infected men who have sex with men in HIV care: Project enhance. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:S117–s126. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lightfoot M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Tevendale H. An HIV-preventive intervention for youth living with HIV. Behav.Modif. 2007;31(3):345–363. doi: 10.1177/0145445506293787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cornman DH, Kiene SM, Christie S, Fisher WA, Shuper PA, Pillay S, et al. Clinic-based intervention reduces unprotected sexual behavior among HIV-infected patients in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: results of a pilot study. JAIDS. 2008;48(5):553–560. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31817bebd7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. New York: Guilford Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Gilbert P, Ciccarone D, Gansky SA, Bangsberg DR, Clanon K, McPhee SJ, et al. Interactive “Video Doctor” Counseling Reduces Drug and Sexual Risk Behaviors among HIV-Positive Patients in Diverse Outpatient Settings. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(4):1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001988. e1988. *This report describes a novel, software- based PfP intervention for PLWH which is implemented in health care settings, and which has been found to be effective, which could also be cost-effective.

- 80.Gerbert B, Danley DW, Herzig K, Clanon K, Ciccarone D, Gilbert P, et al. Refraining 'Prevention with Positives': Incorporating Counseling Techniques That Improve the Health of HIV-Positive Patients. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20(1):19–29. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bonell C, Hargreaves J, Strange V, Pronyk P, Porter J. Should structural interventions be evaluated using RCTs? The case of HIV prevention. Soc.Sci.Med. 2006;63(5):1135–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jones DL, Weiss SM, Bhat GJ, Bwalya V. Influencing sexual behavior among HIV-positive Zambian women. AIDS Care. 2006;18:629–634. doi: 10.1080/09540120500415371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schiff M, El-Bassel N, Engstrom M, Gilbert L. Psychological Distress and Intimate Physical and Sexual Abuse among Women in Methadone Maintenance Treatment Programs. Soc.Serv.Rev. 2002;76(2):302–320. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sikkema KJ, Wilson PA, Hansen NB, et al. Effects of a coping intervention on transmission risk behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS and a history of childhood sexual abuse. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:506–513. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318160d727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jones TS, Vlahov D. What we can learn from the INSPIRE study about improving prevention and clinical care for injection drug users living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:S31–S34. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318157892d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Purcell DW, Latka MH, Metsch LR, et al. for the INSPIRE Study Team. Results from a randomized controlled trial of a peer-mentoring intervention to reduce HIV transmission and increase access to care and adherence to HIV medications among HIV-seropositive injection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46 Suppl 1:S35–S47. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815767c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mausbach BT, Semple SJ, Strathdee SA, et al. Efficacy of a behavioral intervention for increasing safer sex behaviors in HIV-positive MSM methamphetamine users: results from the EDGE study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Margolin A, Schuman-Olivier Z, Beitel M, et al. A preliminary study of spiritual self-schema (3-S+) therapy for reducing impulsivity in HIV-positive drug users. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63:979–999. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Healthy Living Team. Effects of a behavioral intervention to reduce risk of transmission among people living with HIV: the healthy living project randomized controlled study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:213–221. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802c0cae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Temoshok LR, Wald RL. Integrating multidimensional HIV prevention programs into healthcare settings. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:612–619. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817739b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Remien RH, Berkman A, Myer L, et al. Integrating HIV care and HIV prevention: legal, policy and programmatic recommendations. AIDS. 2008;22 Suppl 2:S57–S65. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327437.13291.86. **This report describes some interesting and important critiques of PfP interventions to date, and some very useful strategies to utilize in order to ensure that future PfP interventions are more effective.

- 92. West GR, Corneli AL, Best K, et al. Focusing HIV prevention on those most likely to transmit the virus. AIDS Educ Prev. 2007;19:275–288. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.4.275. **This report describes populations for which it is especially important to develop, implement, document efficacy, and disseminate PfP interventions.

- 93.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kiene SM, Simbayi LC, Abrams A, et al. High rates of unprotected sex occurring among HIV-positive individuals in a daily diary study in South Africa: the role of alcohol use. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:219–226. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318184559f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Altice FL, Sullivan LE, Smith-Rohrberg D, et al. The potential role of buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid dependence in HIV-infected individuals and in HIV infection prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:S178–S183. doi: 10.1086/508181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ogilvie GS, Palepu A, Remple VP, et al. Fertility intentions of women of reproductive age living with HIV in British Columbia, Canada. AIDS. 2007;21:S83–S88. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000255090.51921.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC, Jr, et al. Retention in care: a challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1493–1499. doi: 10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Park WB, Choe PG, Kim S-, et al. One-year adherence to clinic visits after highly active antiretroviral therapy: a predictor of clinical progress in HIV patients. J Intern Med. 2007;261:268–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Singer M. Introduction to syndemics: a systems approach to public health and community health. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kalichman S. Co-occurrence of treatment nonadherence and continued HIV transmission risk behaviors: implications for positive prevention interventions. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:593–597. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181773bce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fisher JD. Integrating HIV prevention into clinical care for PLWHA in South Africa. 2007 R01 MH077524-01. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Norton WE, Fisher WA, Fisher JD. Achieving the potential of HIV prevention Interventions: critical global need for collaborative dissemination efforts. AIDS. 2008;22:1–3. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328312c76a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kalichman SC, Cherry C, White D, et al. Altering key characteristics of a disseminated effective intervention for HIV positive adults: The ‘Healthy Relationships’ experience. J Prim Prev. 2007;32:259–267. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0083-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Koester KA, Maiorana A, Vernon K, et al. Implementation of HIV prevention interventions with people living with HIV/AIDS in clinical settings: challenges and lessons learned. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:S17–S29. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]