I recently had the privilege to participate in a medical mission trip to Haiti. The experience was both challenging and rewarding. The motivation for this article is to encourage anyone who might consider volunteering for medical mission work. I would like to share a few stories about some of the people I met as a result of this particular trip.

Often others express interest in medical mission work but relate that they do not know where to start or do not have the time to become involved. While preparing for this trip to Haiti, I became aware of a wonderful new resource here at Baylor Health Care System (BHCS) known as the Faith in Action Initiative. Joel Allison, president and chief executive officer of BHCS, having a desire to take the Christian ministry of Baylor to the next level, established this program to organize and direct the charitable donations provided by BHCS when needs arise similar to those of the recent Haitian earthquake. This department matches volunteers with various resources to help fill needs around the world and in the community. The director of the program, Donald Sewell, previously worked for Texas Baptist Missions Foundation for 12 years. He has been asked to formalize the processes and strategy and have his department act as a hub of much of the charitable activity and volunteerism that has previously been less organized. For example, I made several inquiries to various departments about the possibility of obtaining donated medical supplies and medications for the trip to Haiti. I was met with much enthusiasm from everyone, but little progress was made until I was directed to Don Sewell. One of my initial challenges was to fill two large suitcases, the maximum allowed by the Haitian Department of Customs, with the appropriate medical supplies and medications. With very short notice, the Faith in Action Initiative helped fill the suitcases beyond airline weight baggage limits. One of the medications provided, a large supply of albendazole, was particularly helpful in making an impact, successfully treating many of the children who suffered with intestinal worms.

BACKGROUND ON MISSION WORK FOR THE HAITI EARTHQUAKE

Numerous articles and stories have chronicled the heroic activities of medical professionals who volunteered their time and expertise to go to Haiti and assist with the enormous job of medical care for the victims of the January 12, 2010, earthquake. Teams of physicians, nurses, medical therapists, and many other specialists arrived in Haiti to assist with immediate needs, and the effort has continued over the months since, gradually changing as the needs of the people and country have changed. The most fascinating and intense stories obviously surround the initial response effort—which involved hundreds and even thousands of crush injuries, amputations, and other acute trauma cared for in a makeshift setting with tent hospitals or with field surgeries performed with head lamps and without anesthesia.

As the acute care needs tapered down, Haiti has slowly returned to its usual state, which is extreme poverty with little to no access to medical care, poor nutrition, and little community or governmental support. Port au Prince is a city in ruins, with most buildings leveled by the earthquake (Figure 1). People continue to live in tent cities or other crudely constructed shelters, often right outside the front door of the destroyed house or building where they previously lived. The median of the main highway through the middle of the city is home to many of these tents and shacks (Figure 2). Some people are too afraid to sleep indoors, and most simply have nowhere else to live. Streets are crowded with people milling around, most without jobs, many without family.

Figure 1.

A building damaged through the Haitian earthquake of January 2010.

Figure 2.

Tents set up on the highway median in Port au Prince, Haiti.

Immediately following the earthquake, organizations such as International Medical Corps, Doctors Without Borders, Partners in Health, Hope for Haiti, Red Cross, and Cure International provided medical assistance. My flight to Port au Prince was at least 90% filled with volunteers, many of whom worked with the previously mentioned organizations. The others were Haitians returning home or going to see family. In addition to those involved with the relief organizations mentioned above, a large percentage of volunteers are affiliated with various Christian organizations and churches. These volunteers include medical personnel who join with other relief organizations, medical mission teams who bring their own supplies and provide free medical clinics, and many others who are willing and able to help in any way they can. I met several teams intending to help with clean-up efforts and others functioning as construction and building crews.

MY TRIP

I joined a medical team from Tennessee that was affiliated with Baptist Global Response of the International Mission Board division of the Southern Baptist Convention. The medical mission trip needed to be fully equipped by those participating, since nearly no supplies and support were available in Haiti. The team from Tennessee had no difficulty filling their suitcases with generous donations from friends, family, and church members. I also received a surplus from numerous sources, including a children's mission class from First Baptist Church in Wills Point, Texas. Most medications were generously donated by Baylor University Medical Center at Dallas with the help of Faith in Action Director Don Sewell. Contributions in the form of supplies and medications were given by several other BHCS physicians and staff, including Dr. Louis Sloan, Dr. Amy Anderson, Dr. Paul Neubach, Dr. Katherine Little, Dena and Dr. Charlie Risinger and the staff of Baylor Family Medical Center at Terrell, and Ronnie Rose from Baylor Ellis County, just to name a few. Additionally, my partners in American Radiology Associates were very helpful, providing the necessary work coverage on short notice.

On the plane ride over from Miami, I sat with a man named Stephen from central Kansas. His church has had a decade-long relationship with several churches in Haiti. He was currently going to Haiti with a large team of other church members to help rebuild their sister church, which was destroyed in the earthquake. He had been to Haiti several times before the earthquake but had not been since.

On the flight, we were talking about the various needs of the people, mostly about their needs for shelter, nutrition, and medical care. He told me about an orthopedic surgeon friend of his who had served in the first few weeks following the earthquake. One particular patient was a 12-year-old girl who had been badly burned over her entire right arm. The surgeon had seen her in the field hospital a few days after the earthquake and had thoroughly cleaned and bandaged her wounds. The girl had stayed in the hospital for a few days to be stabilized. When the orthopedic surgeon returned to Haiti 2 weeks later, this same young girl came to the hospital for treatment, except this time she had a serious systemic infection originating from her initial burn wound. Her family had been convinced by the local voodoo “doctor” or “priest” that the foreign doctors were trying to harm her. The voodoo doctor had removed all the bandages and in some bizarre ritual had smeared goat dung over the burn wounds. The orthopedic surgeon had left the girl 2 weeks earlier, no doubt joyful that he had participated in helping this young girl, only to return and find her septic and near death because of her environment. Often the local obstacles are passively related to a lack of resources and access to medical care; at other times missionaries are fighting against local customs, religions or belief systems that actively work against their best efforts.

Stephen and I talked for most of the flight about what each of us would be doing over the next week. I saw him and his family again as I was leaving the country a week later and we shared stories and photos. He and his team from Kansas had rebuilt the church from the ground up in 1 week and had a church service that Sunday before leaving.

ASSOCIATES AND TEAM MEMBERS

I was picked up from the airport by Sam and Delores York and Parker Hall. Very quickly in our initial introductions (as we had never communicated, even by e-mail), we realized that we were all Texans. Sam and Delores York, from San Angelo, are career missionaries who have been stationed in Haiti for 8 years. They have lived most of the time in the mountains ministering to the locals in various ways. Since the earthquake, they have moved into Port au Prince into the Haitian Baptist Convention property. The property has a two-bedroom shack with occasional running water and electricity powered by a gasoline generator right outside the kitchen window. The rest of the half-acre cinderblock–walled-in property has seven heavy-duty tents erected for the teams of volunteers who rotate through. The move to downtown Port au Prince from the countryside has allowed them to help with the relief effort personally as well as host the many teams of volunteers that have come into the country in affiliation with Baptist Global Response. In the brief amount of time that I got to spend with this wonderful couple, I was able to see their gentleness of spirit and the toughness that allows them to serve in this way.

Parker Hall, originally from Mesquite, Texas, is a recent graduate of the University of Texas at Austin. Immediately following graduation, he joined the Journeyman program, a group of young college graduates who serve as Baptist missionaries for 2 years in remote locations around the globe. Parker's first assignment was in urban Lima, Peru, ministering to the city's large population of prostitutes. After 9 months in that setting, and as a direct result of the need created by the earthquake, he was asked to consider relocating to Haiti. Parker's enthusiasm for the language and culture and his constant smile and laughter make him a magnet for both children and adults.

I stayed with the Yorks and Parker and accompanied them to church on Sunday morning. Their current church is an open-air temporary structure standing next door to the original church building that was leveled in the earthquake (Figure 3). The temporary church was constructed using cinderblocks, tarps, and anything else that helped provide structure and cover. The church pastor is an older gentleman, who, along with his three sons and their families, also operates an orphanage. The pastor and his family have taken in at least 12 earthquake orphans and personally assumed responsibility for their care and education (Figure 4). Currently, many of the earthquake orphans live in tents that were donated and erected at the pastor's home. Sam York built a water well for the family in their yard and taught them how to dig and construct the well, so they could help their neighbors do the same (Figure 5). That Sunday morning at church, the orphans sang several of the worship songs, which were usually about Bible stories and were sung in Creole French with typical Creole melodies and rhythms. Watching these men and their families care for, mentor, instruct, and educate these young children was one of the highlights of my trip and gave me a glimpse of the future of Haiti.

Figure 3.

The temporary church associated with the Haitian Baptist Convention in Port au Prince. The original church was destroyed by the earthquake.

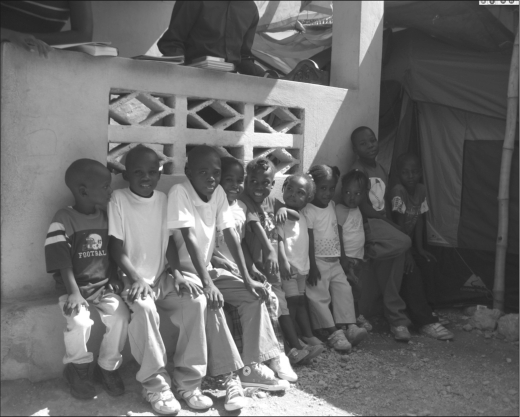

Figure 4.

These children were all orphaned by the earthquake. Notice their tents in the background. They are currently being cared for by the church pastor.

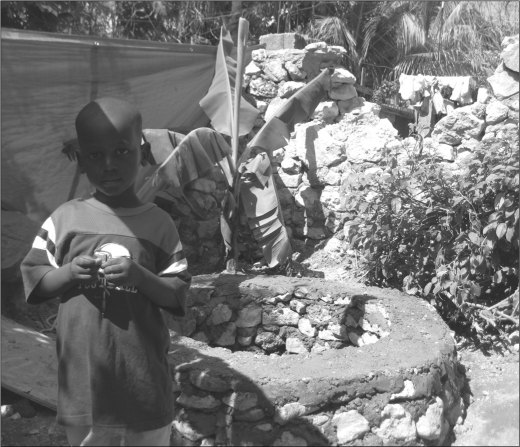

Figure 5.

An orphan boy standing in front of a well that was dug by Sam York for the orphanage.

Paul Scott was the mission team leader and only nonmedical member. He was a career missionary in Venezuela for about 8 years in his 20s and 30s. He is now the community impact pastor for Hilldale Baptist Church in Clarksville, Tennessee. Paul served not only as the spiritual leader of the group but also as pharmacist and patient counselor. His sense of humor and upbeat attitude were invaluable to the team. We began each morning with breakfast and a “word” from Paul to start the day off with the right perspective. He began by acknowledging that we probably all felt unprepared and maybe even inadequate for the task and that we might question what we were doing there. In fact, few were completely prepared for this type of service. When out of our comfort zone, he said, rather than shrink back we should rely on God and lean forward into whatever we are asked to do that day. His morning devotionals were inspirational to energize us to give our very best to each individual that we encountered.

Lisa Becker, a nurse anesthetist, acted as our pharmacist. She was always the first one in the clinic each morning, organizing and getting ready. The two nurse practitioners, Phyllis Egbert and Lori Treanton, saw patients, performing the function of doctors. Although out of their comfort zones, they stepped up and met the need. Garrett Hogan, an emergency medical technician, and Susan Johnson, a nurse, took histories and measured vital signs on every patient. Each of these individuals expressed that their lives were touched and forever changed by at least one and often several of the patients and other Haitians that we interacted with over the week.

One of the team members, Nathalie Parent, a French Canadian, is fluent in the Creole language. She came as one of our interpreters and was arguably our most valuable player. She truly loved what she was doing, and it showed in her interaction with the Haitians. One moment she would be strictly maintaining order in the waiting area, aggressively telling patients where to sit and wait their turn to be seen, and the next moment she would be in patients' personal space, intensely focused, listening to their needs, hugging them and expressing genuine concern.

Wadley St. Hilaire was my Creole translator at the clinic. Wadley not only allowed me to communicate with the people, but also provided me a glimpse of the personal tragedy associated with the earthquake. Wadley lost his best friend and a first cousin in the earthquake and knew many others who lost their lives or were injured. He had recently graduated from secondary school but was not able to attend university due to limited personal resources and limited opportunity nationally. The day after the earthquake, Wadley and a friend walked to downtown Port au Prince and created a personal video story of the earthquake tragedy and its chaos. The video is unedited and difficult to watch but gave me a more detailed look into the tremendous pain and suffering that this earthquake caused. Despite his meager upbringing, daily hardships, and seemingly dim future, Wadley maintains an infectiously positive attitude. Like many other 20-year-olds, he has dreams of what he would like to become. He spoke of a desire to become a surgeon, likely inspired by the great need that this earthquake caused. The future of Haiti almost certainly rests in the hands of young men like Wadley, and I believe the only thing that he and many other young Haitians lack is the opportunity to better themselves and therefore positively impact their country.

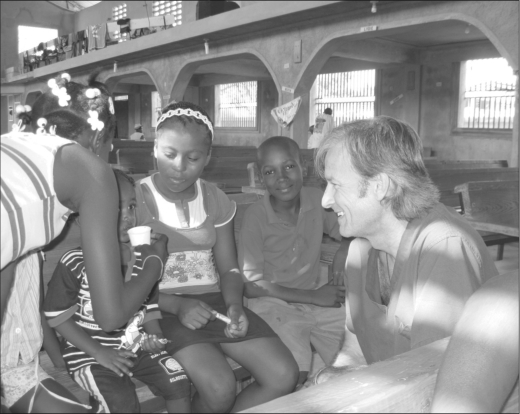

I thoroughly enjoyed the time that I got to spend with the amazing group of people who made up the clinical team (Figure 6). What I will remember most is the sense of humor that we shared. We laughed a lot. The sleeping environment was, for all practical purposes, camping. We had no running water and no electricity, and the “facilities” and showers were the subject of many of our funniest stories. The experience brings a new depth to appreciating what we realize each day here at home.

Figure 6.

The missionary team (left to right): Lori Treanton, Paul Scott, Phyllis Egbert, Nathalie Parent, Lisa Becker, Susan Johnson, Garrett Hogan, and Greg Schucany.

THE CLINIC AND MEMORABLE PATIENTS

Our free medical clinics were conducted in a section of Port au Prince called Carrefour. The medical clinic was organized by Baptist Global Response and Carrefour First Baptist Church, using the church building as the actual clinic. The church is made out of cinderblocks and concrete and fortunately has a steel beam and tin roof. Although the church is much closer to the epicenter of the earthquake than downtown Port au Prince is, this building survived, probably because of superior construction techniques and the tin roof. Most of the damage affected buildings with heavy concrete and cinderblock ceilings and roofs, which did not allow for the building to sway instead of crumble. The church advertised the free medical clinic for several weeks before our arrival. By about 6:00 am each day, people were lined up waiting to be seen.

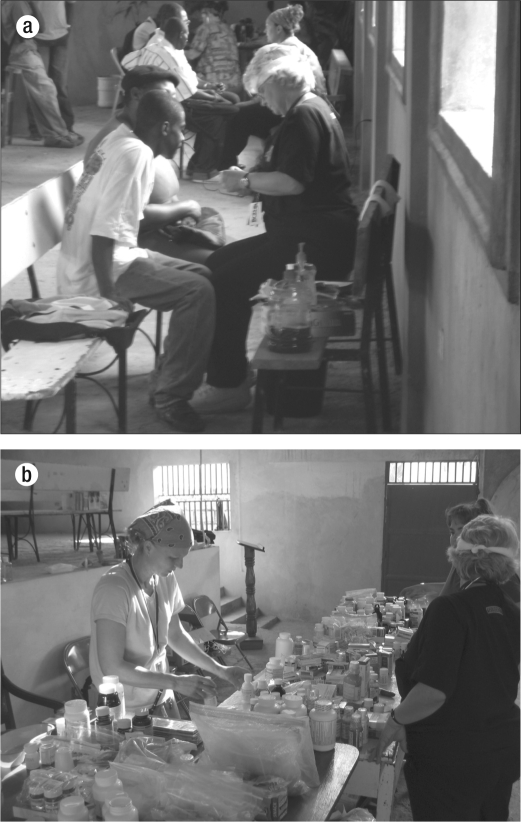

The patients entered from the street, and we saw patients in the main sanctuary. Patients sat in the pews, and stations were set up for vitals and history taking, nurse and physician consultation, a single small private examination room, and our fairly extensive pharmacy and supplies at the front of the church (Figure 7). Church members and many local young men helped organize, set up, and provide support for the clinic.

Figure 7.

The clinic held in Carrefour Baptist Church about 12 miles from the earthquake epicenter: (a) consultation area and (b) pharmacy.

In the span of a week, our team saw over 500 patients with medical conditions of all levels of severity. Patients came in for symptoms suggesting the common cold to those associated with gastrointestinal worms, typhoid, and malaria. The medical need is overwhelming, much of it the result of the recent earthquake. However, similar to other Third World countries, most of the need is related to poverty and the poor condition of Haiti in general. Even prior to the earthquake, the United States and other countries have sent in many volunteers providing medical and humanitarian relief.

Our team was challenged in new ways, stretched beyond what we were used to and in situations and circumstances that we in America seldom encounter. We often found ourselves without the simple things that we take for granted.

On our fourth evening, Nathalie Parent offered antimalaria medication from her personal luggage, so we could include it in our pharmacy. We didn't have a supply of antimalarials with us, and her pills would be enough to treat one person if we did encounter a case. The next day, we had closed our clinic late in the day, as usual, when a woman and her granddaughter came to the back door requesting to be seen. The young girl, about 12 years old, had brought a plastic bottle filled with her urine, which was dark brown (Figure 8). She appeared lethargic. Her mucosal membranes and palpebral conjunctiva were pale, and she had a faint yellow tint to her conjunctiva. Her vital signs demonstrated signs of hypovolemia with tachycardia and mild hypotension. My Haitian translator relayed the other symptoms including “back and belly pain” and fevers. The presumed diagnosis was malaria. We were able to hydrate and treat her with the antimalarials that Nathalie provided.

Figure 8.

A young girl with malaria. The urine specimen in the bottle is dark brown, related to hemoglobinuria.

An example of the improvisation often necessary in medical mission trips also involved one of our favorite patients. A young boy, about 4 years old, was brought to the clinic by his four sisters, the oldest of whom was 11. Two of his fingers had been crushed by a falling cinderblock; both were swollen and red, and one was partially amputated. He had no father, and his mother could not take a day off from work to attend our clinic. The boy would not allow anyone within 10 feet of his hand to adequately evaluate the injury. We had no sedatives to use before examining him. Paul Scott called the Tennessee Baptist Disaster Relief folks who were working across town in Port au Prince. They had a small supply of chloral hydrate and were willing to let us have some. With the help of the translator, it was determined that the children lived nearby and could return the next day.

After we closed the clinic that evening, the pastor of the church phoned for a “tap-tap,” a colorful, small pickup truck with bench seating in the back for passengers. These cabs are individually owned, heavily used jalopies that are patched together. They routinely break down in the middle of the road (if you can even call it a road, but that's another story), and all repairs are made where the car is stranded. During the week we saw multiple tap-taps in the middle of the highway, in the midst of everything from a tire change to a transmission repair. Paul had to travel across Port au Prince, about a 2-hour round trip, to borrow the chloral hydrate. The rest of the team from Tennessee wanted to go along and left the church about an hour before dusk. The US State Department had in March issued an official travel warning to US citizens to avoid Haiti because of the dangers involved. Kidnappings and murders were at a new high in the aftermath of the earthquake. The Port au Prince prison had been damaged in the earthquake, and most prisoners had escaped and reformed dangerous gangs that roamed the streets, mostly at night. Despite the risk involved, the team was intent on getting the needed supplies. This little boy did not have other options for medical care. About an hour into the trip, which was already complicated by bad directions and the driver not knowing exactly where he was going, the tap-tap broke down in the middle of a very chaotic road. Luckily, Paul's cellphone worked, and he called for help. After a slight though nerve-wracking delay, the Tennessee Disaster Relief volunteers sent a truck to pick them up. They continued on to their destination to retrieve the needed supplies and then traveled back across Port au Prince at night, this time accompanied by two armed Haitian guards. The next day we were able to sedate the young boy (which, incidentally, highly amused his sisters) and adequately evaluate, clean, and bandage his fingers (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

A 4-year-old boy receiving sedation in order to evaluate and treat the crush injury of his fingers.

REFLECTIONS

One of the troubling components of a medical mission trip is the feeling that the need is overwhelming and anything accomplished is just a “drop in the bucket.” Yet, the question about making a difference depends on your perspective. Short-term medical mission trips are by definition a temporary solution to a chronic problem and therefore might be viewed as not making a lasting difference in the health care of a group of people. A global solution to the health care of Haiti or any other poor Third World country is another issue altogether. At the same time, it is good to remember that each patient that comes to one of these free medical clinics has a present need, whether acute or chronic, and does not personify the problem as a whole.

There is a parable about a young boy walking along the beach who happens upon hundreds of starfish that have been washed up and are in danger of dying if left on the sand. He begins to take one starfish at a time and throw it back in the ocean. A man walks by and suggests that the boy is wasting his time because there are too many starfish to save; with all the other starfish in the world, he asks if what the boy is doing “really matters.” The young boy holds up one of the starfish and says, “It matters to this one.”

Jesus came to save the world, but he did not physically heal everyone he encountered. I once heard a pastor address this issue with an analogy from the Gospel of Luke where Jesus is with a large crowd, many of whom specifically came to see him to be healed from some affliction. He was with this crowd on one side of the Sea of Galilee and asked his disciples to take him to the other side, apparently with the intent of healing one man there. This biblical illustration parallels that of the starfish, in that the care given to that one individual does make a difference. We are asked only to deal with this individual at this moment, and it does make a difference to that person.

Seeing the devastation and general desperation of an entire country was difficult to witness, and the ongoing support provided by the rest of the world will be a necessity for the foreseeable future if Haiti has any chance of recovery. Having the opportunity to become involved in the relief effort was a blessing and was rewarding in more ways than I can express. One of the blessings that I have experienced with this medical mission trip is the relationships and new friendships that I have made in preparation for and then during the trips. These are people that I will never forget. Although I may never cross paths again with all of the people that I encountered on the trip, we will always be linked by this one brief experience. Throughout the week we talked, shared stories, and laughed, and by the end we felt like we knew one another. These new friends have their own story of what led them to this point in their lives, but the common link was their desire to serve others in love. You will often hear people who have been on medical mission trips say that they went in order to “give back” or to serve those who are less fortunate. They will also tell you that they have received something even more valuable, this intangible something that leaves you feeling more satisfied, blessed, and thankful.