Abstract

Objective

A recently published instrument (PRECIS) was designed to assist investigative teams in understanding the various design decisions that need to be made regarding pragmatic versus explanatory trials. Our team used this instrument during an investigators’ meeting to organize our discussion regarding the design of a planned trial and to determine the extent of consensus among the study investigators.

Study Design and Setting

The study was descriptive in nature and occurred during an investigator meeting. After reading and reviewing the ten PRECIS criteria, the team made quantitative judgments of the planned study regarding each PRECIS criteria to reflect initial, ideal and final study design perceptions.

Results

Data indicated that the final study design was more explanatory in nature than the preliminary plan. Evidence of consensus was obtained.

Conclusion

The investigative team found that applying PRECIS principles were useful for (1) detailing points of discussion related to trial design, (2) making revisions to the design to be consistent with the project goals and (3) achieving consensus. We believe our experiences with PRECIS may prove valuable for trial researchers in much the same way that case reports can provide valuable insights for clinicians.

Keywords: clinical trial, research design, knee, arthroplasty, pain, coping skill

Introduction

Pragmatic (or effectiveness) trials are designed to estimate intervention effects under usual conditions of clinical application while explanatory (or efficacy) trials determine intervention effects under ideal conditions. Pragmatic designs allow for a more seamless application to clinical practice while explanatory trials allow for a better understanding of the mechanism(s) for any treatment effect found. There continues to be discussions in the literature regarding the strengths and weaknesses of clinical trials that are designed to be either more pragmatic or more explanatory in nature.(1–9) A special series of papers was recently published that examined issues related to pragmatic versus explanatory approaches to the design of randomized clinical trials.(2–9) Among these was a paper that proposed the use of an instrument (the PRECIS) that could be used to assist researchers in designing studies and in particular, to clarify and refine the design’s position along the pragmatic-explanatory continuum.(8)

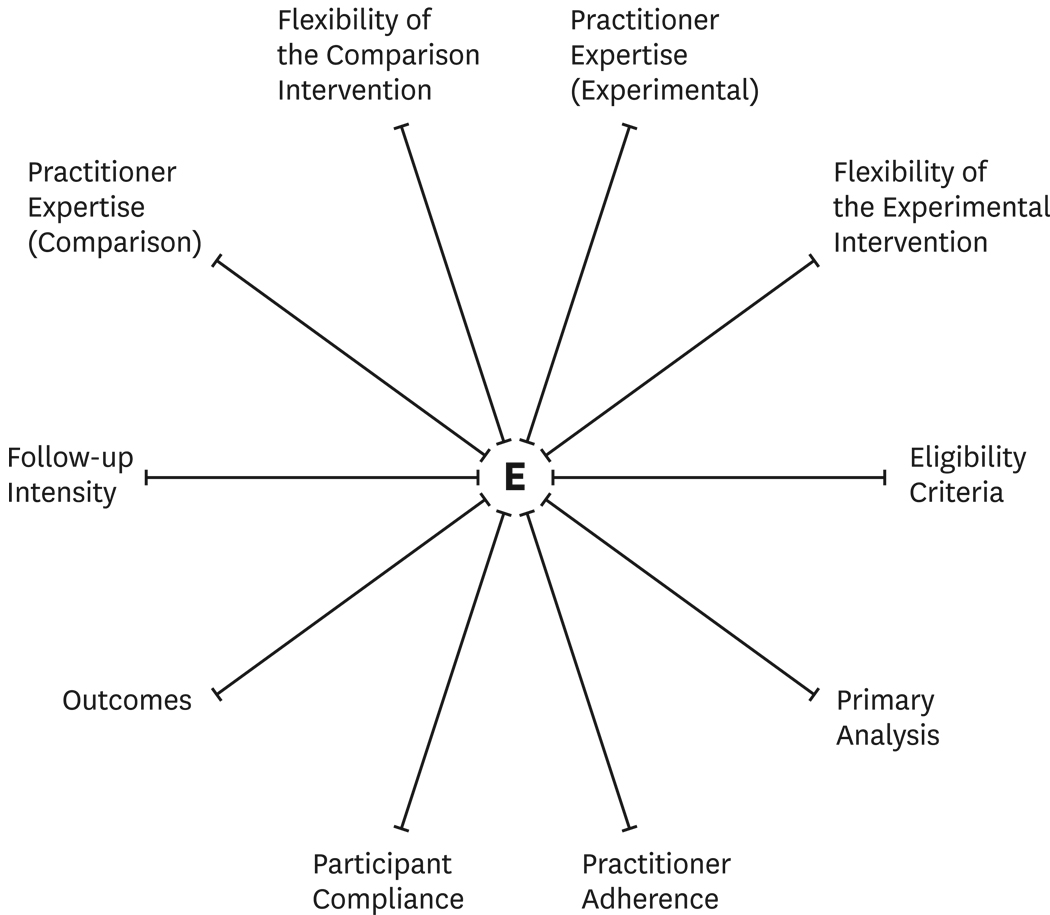

Thorpe and colleagues used an informal consensus-based approach to identify and define 10 key domains (see Table 1) that were judged to be most important in distinguishing pragmatic from explanatory trials. Briefly, the 10 domains address eligibility criteria, practitioner expertise, flexibility in the application of the experimental and control interventions, nature of the primary outcome and intensity of follow-up, intensity of measuring participant and practitioner compliance, and finally, the scope of the analysis. In addition to proposing the 10 domains, the authors recommended use of a PRECIS “wheel graph” or spider plot to quantify where along the pragmatic-explanatory continuum each domain is located for a particular study (see Figure 1). For each study domain, a mark that is placed nearer the hub (see E on Figure 1) is considered to reflect the study’s reliance on an explanatory approach while a mark at or near the rim reflects the study’s reliance on a pragmatic approach.

Table 1.

Summary of the ten PRECIS domains

| Domain | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Eligibility criteria for trial participants |

| 2 | Extent of flexibility in application of the experimental intervention |

| 3 | Degree of practitioner expertise in applying and monitoring the experimental intervention |

| 4 | Extent of flexibility in application of the comparison intervention(s) |

| 5 | Degree of practitioner expertise in applying and monitoring the comparison intervention(s) |

| 6 | Intensity of follow-up of trial participants |

| 7 | Nature of the primary outcome |

| 8 | Intensity of measurements of participants’ compliance to study protocol and whether compliance improving strategies are used |

| 9 | Intensity of measurements of practitioners’ adherence to study protocol and whether adherence improving strategies are used. |

| 10 | Specification and scope of analysis of primary outcome |

Figure 1.

The blank PRECIS wheel or spider graph indicating the pragmatic-explanatory continuum. Marks closer to the hub of the wheel indicate more explanatory characteristics while marks closer to the rim of the wheel indicate more pragmatic characteristics. (Reprinted with permission from the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology)

Our research team recently received a National Institutes of Health (NIH) clinical trial planning grant to plan a randomized clinical trial of a pain coping skills training intervention for patients scheduled for knee arthroplasty. The research team is multidisciplinary and includes investigators from Biostatistics, Internal Medicine, Orthopaedic Surgery, Physical Therapy, Psychology and Rheumatology. In addition, some investigators had a history of designing and completing trials that tended toward more pragmatic approaches, while others had a history of conducting trials using an explanatory approach. Given the diversity of backgrounds and training in our group, we saw a need for an instrument that would assist us in developing consensus when designing the trial. We decided to use the PRECIS during our investigator meeting to assist us in confronting this pragmatic-explanatory continuum and in developing consensus for the planned trial. The purpose of this brief report is to describe how use of PRECIS facilitated discussion and decisions regarding the pragmatic-explanatory continuum and to illustrate how other teams of researchers could potentially benefit from using PRECIS while planning clinical trials.

Methods

The trial being planned is a 3-arm multicenter randomized trial of a pain coping skills training intervention for patients who are scheduled for total knee replacement surgery. Patients will be randomized to either a pain coping skills training condition, an educational control condition or a usual care condition. The investigative team had received funding to plan the RCT from the National Institute of Arthritis Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (1R34AR056727-01). The purpose of the funding was to finalize plans for the clinical trial, develop a Manual of Procedures for the trial and to recruit clinic sites. We had a 1-day in person meeting to plan the study design which was attended by seven study investigators (authors of this paper).

Applying PRECIS to the Design of the Trial

Prior to the meeting, the paper by Thorpe and colleagues was distributed and all investigators were asked to read the paper.(8) The team began the meeting by discussing the importance of clarifying whether the trial should be more heavily oriented toward a pragmatic or an explanatory approach. Prior to the study design phase of the meeting, the team reviewed and discussed each of the 10 PRECIS criteria (see Table 1). Because the team had already developed a tentative design for the NIH submission, each member was asked to reflect on that tentative design and complete a PRECIS design wheel by placing a mark along each of the ten lines on the wheel. Each arm of the PRECIS wheel was four centimeters in length with the zero point at the hub of the wheel and four centimeters on the rim of the wheel. This “initial” scoring represented where along the continuum each team member believed the tentative study design features were located prior to any formal in-person discussion. Each investigator was given approximately 5 minutes to complete the wheel and all marks were made while blinded to the scores of other team members.

Immediately following the first completion of the PRECIS wheel, the investigators were asked to complete the wheel for what they believed was their “ideal” version of the study, based on their own experience and opinions. Investigators represented a variety of specialties with some more inclined toward explanatory trials while others preferred a pragmatic approach. We wanted to capture each investigator’s “ideal” design features to determine the extent of variation if each investigator was designing the study himself. Team members were again blinded to scores of others and were not shown their own scores from the first administration of the PRECIS wheel. The “ideal” versus “initial” scores were compared using simple visual comparisons of group mean scores for each item. We also were interested in determining how closely the design as it was rated based on the first application approximated each investigator’s views of what they perceived to be the ideal design. We believed that this approach would facilitate discussion during the remainder of the meeting.

Following this second application of the wheel, the investigators discussed details of the study. As part of this discussion, each item from the PRECIS was reviewed and revisions were made to the original design. For example, in regard to practitioner expertise, the team agreed that practitioners providing the pain coping skills intervention should be as skilled as possible, preferably PhD trained psychologists with experience in dealing with patients with persistent disease-related pain. Our original plan did not specify the extent of training required for the psychologists. For practitioner adherence to the study protocol, the team agreed that rigorous ongoing assessment would be needed to assure that the intervention was provided as intended. Prior to the meeting we had not achieved consensus on the need for practitioner adherence assessment.

At the end of the 1-day meeting, a third application of the study wheel was completed by the team. The purpose of this “final” scoring of the wheel was to determine the extent to which there was consensus among the team on the final design.

To score the marks on the PRECIS wheels, the distance from the hub to each mark was measured with a centimeter ruler and recorded. Smaller numbers reflect scores that are closer to an explanatory trial while larger scores are indicative of more pragmatic trials. To describe the scores and the extent of variation in investigators’ scores for each of the three scorings on the PRECIS wheel, we calculated the mean and standard deviation across the 10 categories of items on the PRECIS wheel. No statistical significance comparisons were made because of the small number of observations and because the purpose of the exercise was descriptive in nature.

Results

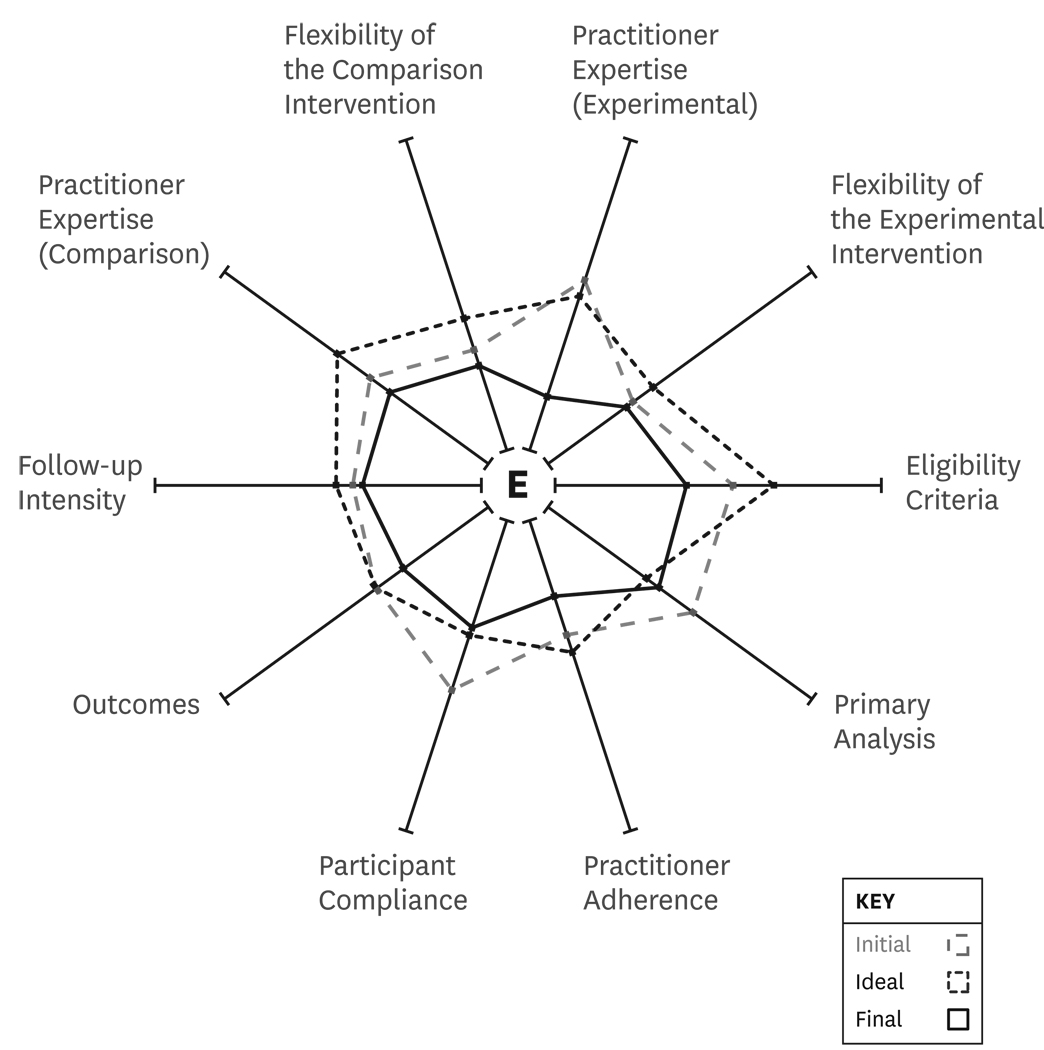

The scores for the three completed versions of the PRECIS wheel are listed in Table 2. Figure 2 illustrates the mean PRECIS wheel scores for the “initial”, “ideal” and “final” applications. Figure 2 indicates that, prior to the in-person meeting, the study schematic depicted a trial that was approximately mid-way along the pragmatic-explanatory continuum. When the meeting was completed (final scores on Table 1 and Figure 2) the study design looked more like an explanatory study with several items moving closer to the hub of the PRECIS wheel as compared to the “initial” or “ideal” scores. In addition, the standard deviations for most of the “final” items were smaller, which suggested reduced variation (i.e., greater consensus) among investigators. The variation of the scores on the 10 PRECIS items for the “initial” assessment, as reflected by the average standard deviation for the ten PRECIS items was 0.83. For the “ideal” assessment the average standard deviation was 1.16 while the average standard deviation for the “final” assessment was 0.61.

Table 2.

Mean scores and variation in scores across three applications of the instrument for each item in PRECIS*

| PRECIS Category | Application #1 (initial) |

Application #2 (ideal) |

Application #3 (final) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Eligibility criteria for participant | 2.2 | 0.64 | 2.7 | 0.74 | 1.6 | 0.48 |

| Experimental intervention flexibility | 1.3 | 0.70 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.65 |

| Comparison intervention flexibility | 1.3 | 0.58 | 1.7 | 1.20 | 1.1 | 0.47 |

| Experimental intervention practitioner expertise | 2.2 | 1.15 | 2.0 | 1.45 | 0.7 | 0.40 |

| Comparison Intervention practitioner expertise | 1.8 | 1.26 | 2.3 | 1.38 | 1.5 | 0.91 |

| Follow-up intensity | 1.6 | 0.65 | 1.8 | 1.27 | 1.5 | 0.50 |

| Nature of primary trial outcome | 1.7 | 1.06 | 1.7 | 1.43 | 1.3 | 0.53 |

| Participant compliance with prescribed intervention | 2.2 | 0.69 | 1.5 | 0.80 | 1.4 | 0.53 |

| Practitioner adherence to study protocol | 1.5 | 0.68 | 1.7 | 1.01 | 1.0 | 0.34 |

| Analysis of primary outcome | 2.2 | 0.92 | 1.5 | 1.34 | 1.7 | 1.26 |

Marks for each category of the PRECIS wheel were scored from 0 to 4 with 0 indicating a score for a mark placed at the hub of the wheel (indicating an explanatory trial)while a score of 4 would be given for a mark placed at the rim of the wheel(indicating a pragmatic trial).

Figure 2.

A completed PRECIS wheel indicating investigator ratings during the “initial,” “ideal” and “final” assessments.

Changes from “initial” to “final” were fairly consistent with five of seven investigators moving closer to the hub of the wheel for 70% or more of the 10 PRECIS categories. The other two investigators moved closer to the hub on 40% and 20% of the items, respectively. For changes that occurred from the “ideal” to the “final” PRECIS wheel, three investigators lowered their scores (closer to the hub) for 100% of the PRECIS items while the remainder of investigators lowered their scores for between 20% and 50% of the items.

Discussion

Investigators need to make a number of important decisions during the early stages of trial planning, so as to optimally design a trial that is either more pragmatic or more explanatory. When designing a trial one must consider the current state of science, among other factors, when deciding where along the pragmatic-explanatory continuum the study will be positioned.(1) Because we will be examining the effect of an intervention on post-surgical patients, a sample for which the intervention has not been studied, our team ultimately decided on a study design that is more heavily weighted toward an explanatory study. Guidelines provided by PRECIS assisted us in discussing and ultimately making decisions on the various issues related to a study’s tendency toward being more pragmatic or explanatory.

When using the PRECIS criteria, our “initial” design and our "ideal" design both were generally found to be more pragmatic than our “final” design (see Figure 2). We found that PRECIS was helpful in identifying the design elements that investigative team members differed on in regard to the pragmatic-explanatory continuum. The team articulated these differences and discussed the potential benefits of more explanatory approaches over pragmatic approaches given the state of the science. In the end, the team came to a stronger consensus on study design as compared to earlier PRECIS scores.

We found that by explicitly deliberating about the PRECIS design features and by scoring our trial using the PRECIS wheel, we were able to quantify the extent of variation among the investigators and to address these differences during our face-to-face meeting. Our findings suggested that we were able to reduce variation and achieve stronger consensus after discussing principles described in PRECIS.

In conclusion, all members of the investigative team agreed that PRECIS was a useful method for exploring the design of our study and examining the extent to which our study should be designed as either a pragmatic or an explanatory trial. The team indicated that this visual approach to describing trial characteristics was particularly helpful in raising the investigative teams’ awareness of key domains to consider with regard to the pragmatic –explanatory continuum. Investigators were able to label and discuss in detail specific issues related to the trial in a way that appeared to facilitate discussion and allowed for consensus to be reached.

We used a defined approach to applying PRECIS to aid in planning for our study. Other investigative teams may choose a different application of PRECIS which is efficient and effective for them. We applied PRECIS principles to a single trial and shared our experiences. These experiences may prove useful to other trialists during trial planning.

What is new?

The PRECIS instrument can be used to facilitate discussion, make revisions and achieve consensus when designing a randomized trial.

PRECIS seems to be particularly assistive during face-to-face meetings.

This paper outlines an approach other investigator teams can use when designing a trial.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sackett DL. The principles behind the tactics of performing therapeutic trials. In: Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P, editors. Clinical Epidemiology: How to do Clinical Practice Research. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2006. pp. 173–244. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karanicolas PJ, Montori VM, Devereaux PJ, Schunemann H, Guyatt GH. The practicalists' response. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):489–494. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karanicolas PJ, Montori VM, Devereaux PJ, Schunemann H, Guyatt GH. A new 'mechanisticpractical" framework for designing and interpreting randomized trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):479–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maclure M. Explaining pragmatic trials to pragmatic policymakers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):476–478. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oxman AD, Lombard C, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Maclure M, Zwarenstein M. Why we will remain pragmatists: four problems with the impractical mechanistic framework and a better solution. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):485–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oxman AD, Lombard C, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Maclure M, Zwarenstein M. A pragmatic resolution. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):495–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz D, Lellouch J. Explanatory and pragmatic attitudes in therapeutical trials. J Chronic Dis. 1967;20(8):637–648. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(67)90041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M, Oxman AD, Treweek S, Furberg CD, Altman DG, et al. A pragmatic-explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS): a tool to help trial designers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):464–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zwarenstein M, Treweek S. What kind of randomized trials do we need? J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):461–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]