Abstract

Immediate type allergic reactions to medication are potentially life threatening and can hamper drug therapy of several medical conditions. Exact incidence and prevalence data for these reactions in children are lacking. If no alternative drug treatment is available, a desensitization procedure may secure the continuation of necessary therapy. Desensitization is only appropriate in case of a strong suspicion of an IgE-mediated allergic reaction. It should be performed by trained clinicians (allergy specialists) in a hospital setting where treatment of a potential anaphylactic reaction can be done without any delay. In this article, literature describing desensitization procedures for several antibiotics, antineoplastic agents, and vaccines in children is reviewed. In general, desensitization schemes for children differ only in final dose from schemes for adults. Contradictory data were found regarding the protective effects of premedication with antihistamines and glucocorticoids.

Keywords: Children, Drug allergy, Prevalence, Desensitization, Protocol

Introduction and definitions

A drug allergy is an adverse drug reaction that results from a specific immunologic response to a medication. Allergic drug reactions account for about 6–10% of all adverse drug reactions, but up to 10% of fatal reactions in the adult population [17]. There are no prevalence data or incidence data for children regarding these allergic drug reactions.

The World Allergy Organization (WAO) has recommended dividing immunologic drug reactions into immediate type I reactions (onset within 1 h of exposure) and delayed reactions (onset after 1 h), based upon the timing of the appearance of symptoms [10]. The signs and symptoms of type I reactions are directly attributable to the vasoactive mediators released by mast cells and basophils. The most common signs and symptoms are urticaria, pruritus, flushing, angioedema (sometimes leading to throat tightness with stridor), wheezing, gastrointestinal symptoms, and hypotension. Anaphylaxis is the most severe presentation of an IgE-mediated drug reaction.

The drugs most commonly implicated in type I reactions in children are beta-lactam drugs, i.e., penicillins and cephalosporins.

Diagnostic procedures in drug allergy are confined to a detailed clinical history and confirmation of an IgE-mediated reaction. The ENDA (European Network for Drug Allergy, an interest group of the EAACI) has set up guidelines on how to perform these tests [4]. In drug allergy, skin tests and in vitro laboratory tests are cumbersome, because the test reagents are not standardized and may even be harmful for a patient with a severe drug reaction. For this reason, the guidelines provide practical skin test methods, test concentrations, and selection of patients. The drug provocation test, the controlled administration of the suspected drug is considered to be the gold standard in order to confirm the diagnosis drug allergy [ENDA, 1].

Desensitization can be considered in patients who are proven (by positive skin testing or in vitro tests) or are strongly suspected to have an IgE-mediated drug allergy and for whom there are no acceptable alternate drugs (see “Practical proposal”). In patients with (multi)resistant bacteria or patients with multiple drug allergies the effect of a desensitization procedure (successful treatment) may outweigh the risks. Desensitization is a procedure which alters the immune response to the drug and results in temporary tolerance, allowing the patient with IgE-mediated allergy to receive a subsequent course of the medication safely. Desensitization should not be attempted in patients with histories of non-IgE-mediated reactions such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis because even small doses of the drug may induce severe progressive reactions. Desensitization is also not appropriate for patients with type III (IgG-mediated) hypersensitivity drug reactions like hemolytic anemia or nephritis.

Drug desensitization should only be performed by clinicians trained in the technique (usually allergy specialists), in a hospital setting (or outpatient setting under close observation), with intravenous access and necessary medications and equipment to treat anaphylaxis. Pharmacy staff may be consulted prior to the procedure to assist with preparation of the required drug dilutions. Articles concerning protocols are scarce and involve primarily adult patients. In this review, we summarize the known literature concerning pediatric patients who underwent a desensitization procedure.

Review of the literature

For studies describing desensitization procedures in children, PubMed was searched using the combination of keywords “desensitization”, “drug hypersensitivity or drug allergy”, and “child”. The articles found were reviewed for relevance and references were searched where appropriate. Most articles are case reports. Some studies describe case series of adult patients and include one or more children. Very few studies confined to children only were found. This review is limited to desensitization procedures with antibiotics, beta-lactam drugs [8, 22, 23], co-trimoxazole [12, 13, 20], ciprofloxacin [2, 9, 15], cytostatics, carboplatin [5, 14, 18, 19], l-asparaginase [21], and MMR-vaccine [16] in children only.

Procedures

In general, protocols for children differ from those for adults only in the final dose, which should be the daily dose used for adequate therapy.

General principles of desensitization in adult protocols are:

Starting doses range from 10% to 0.00001% of the therapeutic dose (mean 0.001%)

Administration route orally or intravenously

Time interval between two gifts range from 15 to 120 min (mean 30 min)

Total duration of desensitization range from 2 h to 21 days (mean 6 h)

Increment step range from two times to ten times (mean three times)

Whether premedication with corticosteroids and antihistamines reduces the risk of a desensitization procedure is not known.

Antibiotics

Desensitization procedures are reported to be successful in children with symptoms of an IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reaction like urticaria, angioedema, itch, or anaphylaxis. If reliable skin test procedures are available, such as for beta-lactam antibiotics, these should be performed first. Negative results to intradermal tests with penicilloyl-poly-l-lysine and minor determinant mixture reduce the risk of hypersensitivity symptoms upon re-exposure to less than 5%. In these patients, incremental dosing may be chosen, however, studies comparing this strategy to desensitization with regard to safety and efficacy have not been published.

The starting dose for intravenous procedures is generally 1/1,000,000–1/1,000 of full therapeutic dose, but may be higher (1/100) in oral desensitization [2, 8, 9, 12, 13, 15, 20, 22, 23]. During intravenous desensitization the doses are infused continuously over 15–30 min intervals, followed by intravenous administration of the full therapeutic doses. In the oral procedure, dose intervals described range from 15 min (for ciprofloxacin [15]) to 12 h (for co-trimoxazole [12]). Slow or incomplete absorption from the gastrointestinal tract should be taken into account when choosing this dose interval.

Cytostatics

As cytostatics are usually dosed per square meter, the full therapeutic dose is different for every child. Intravenous desensitization with carboplatin starts at a dose of 0.01–1 mg, infused over 1 min (0.01–1 mg/min). Dose increments are made every 15 min by prolonging the infusion time holding the infusion rate constant. When 15–22.5 mg in 15–22.5 min is well tolerated, the infusion rate is increased to 100 mg/h for 1 h followed by 200 mg/h for the remainder of the dose [5, 18, 19].

l-Asparaginase is administered intramuscularly, but intravenous desensitization had been described starting at a 1 IU dose, doubled every 10 min [21].

Intravenous desensitization for methrotrexate is started at 1/1,000 of the full dose in 1.5 h followed by 1/100 in 1.5 h, 1/10 in 6 h and the remaining dose in 24 h every therapeutic cycle [3, 7]. This procedure may necessitate a dose reduction due to increased toxicity as a result of prolonged exposure to methotrexate [3].

Vaccines

Desensitization to MMR-vaccine is performed by subsequent sc administration of 0.05 ml of a 1/100 dilution, 0.05 ml of a 1/10 dilution, and 0.05 ml of the full strength vaccine up to the 0.5-ml dose [16].

Premedication

Premedication can be done with (methyl)prednisolone, antihistamine, and ranitidine with or without montelukast 13, 7, and 1 h, respectively, before start of the desensitization procedure [18, 19, 21] but the protective effects have not been systematically studied. Administration of a full therapeutic dose in combination with premedication, as an alternative to desensitization, resulted in severe hypersensitivity reactions in three of eight patients reacting to E. coli asparaginase [21]. A recent study in children with carboplatin hypersensitivity reactions suggests that administrating a full dose in combination with premedication may be as effective as desensitization without premedication [14]. However, due to its retrospective nature, it cannot be ruled out that desensitization was preferably initiated in children with more severe hypersensitivity reactions.

Symptoms

In almost 50% of the procedures reviewed in this article, symptoms did occur during the procedure. In general, the symptoms could be treated by antihistamines and dose reduction or postponing dose increase [5, 12, 22, 23].

Effectivity

Success rates in the reports described (mostly IgE-mediated allergy) range from 50% to 100% (see Table 1 for details). However, due to the low number of cases reported and lack of comparative prospective studies, success rate may be either lower or higher in reality. Larger case series in adult patients report a success rate of more than 90% in both allergy to antibiotics and to cytostatics.

Table 1.

Summary of published desensitization protocols in children

| Reference | Children (sexe, age, disease) | Drug(s) | Drug allergic symptoms | Result of skin tests | Desensitization protocol | Successful |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown [6] | ♂, 11, CF | Ticarcillin | Burning throat, periorbital edema, pruritus | Positive (penicilline) | IV | Yes |

| Start 1:10E6 of dose, in 50 ml/45 min. Tenfold increases | ||||||

| Stark [22] | ♀, 15, CF | Phenoxymethyl-penicillin | Anaphylaxis | PPL positive | Oral | No (procedure stopped due to bronchospasm) |

| ♂, 8, hyper IgE syndrome | Urticaria | Penicillin G and penicilloic acid positive | Start at dose positive skin test. Doubling every 15 min | Yes | ||

| Turvey [23] | 8 children, 13 adults (1–44) | Multiple antibiotics (51/59 beta-lactam antibiotics) | IgE-mediated reactions | 31/59 with positive skin test | IV | 75% of desensitizations successful. No individual data. No differences between adults and children reported |

| (15 ♀, 6 ♂; 19 CF) | Starting dose 2 micrograms or 1/10E6 of full therapeutic dose infused in 30 min. Followed by tenfold increases | |||||

| De Maria [8] | ♀, 16, CF | Aztreonam, ceftazidime | NR | Positive | IV | Yes |

| ♂, 10, chondritis | Meropenem | NR | Positive | Starting dose 1/10E5 of full therapeutic dose infused in 20 min. Doubling every 20 min | Yes | |

| Soffritti [20] | ♂, 7, allogenic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation after refractory anemia | Co-trimoxazole | Itching rash | Negative | NR (probably oral) | Yes |

| Starting dose 0.000004 mg/0.0002 mg bid, 10-fold increases up to 0.04 mg/0.2 mg, followed by dose doubling | ||||||

| Kletzel [12] | ♂, 7, 3 ♂, 15, 3 adults, | Co-trimoxazole | Rash, dyspnea, swelling | NR | Oral | Yes (except in one child (♂, 15) due to noncompliance) |

| All hemophiliac, HIV+ | Starting dose 1/10,000 of full dose tid, followed by 1/5,000, 1/1,000, 1/500, 1/100, 1/50, 1/10. Then therapeutic dose bid | |||||

| Kreuz [13] | 3 children (3–4y), HIV+ | Co-trimoxazole | Exanthema, fever | NR | Oral | Yes |

| 0.2–0.4–1.6–3.2–4.8–9.2–20–40–80 mg. Dose increased every 3 days, 40 mg/day for 1 week | ||||||

| Erdem [9] | ♀, 2.5, chronic osteomyelitis | Ciprofloxacine | Trembling, tachycardia, flushing, fever, vomiting, headache at first dose | Positive | IV | Yes |

| Starting dose 0.00001 mg in 15 min, tenfold increases. From 0.01 mg twofold increases every 15 min | ||||||

| Kim [11] | ♀, 7, tuberculosis | Rifampicin and isoniazide | Dyspnea, rash, pruritus | Positive | Oral | Yes |

| Starting dose 0.1 mg, twofold increase every 15 min | ||||||

| Morgan [18] | ♀, 4, astrocytoma | Carboplatin | Flushing, urticaria, facial edema, cough | ND | IV | Yes |

| 1–2.5–5–7.5–10–10–25–50-remaining mg. Dose repeated if symptoms occurred | ||||||

| Broome [5] | ♂, 3, astrocytoma | Carboplatin | Cough, congestion, flushing, | Negative | IV | Yes |

| ♂, 7, astrocytoma | Abdominal pain, erythema | Negative | 1–2.5–5–10–25 mg iv push q15 min followed by 25–50 mg infusion q15 min, followed by 331 mg 200 mg/hr continuous infusion | |||

| Ogle [19] | ♀, 3, neurofibromatosis | Carboplatin | Abdominal discomfort, flushing, increased respiratory effort | NR | IV | Yes |

| 0.01–0.1–0.5–1.0–2.5–5–10–22.5 mg push q15 min followed by 66 mg over 44 min. | ||||||

| Soyer [21] | 8, ALL | E. coli l-asparaginase | Anaphylaxis | NR | IV | Yes in 3 cases |

| Starting dose 1 IU, dose doubling every 10 min dose | Five uneventful (3 due to anaphylactic reaction during desensitization) | |||||

| Bouchireb [3] | ♀, 9, astrocytoma | Methotrexate | Urticaria | ND | IV | Yes |

| 1/1,000 of full dose in 1.5 h followed by 1/100 in 1.5 h, 1/10 in 6 h and the remaining dose in 24 h | ||||||

| Caldeira [7] | ♂, 9, ALL | Methotrexate | Urticaria | ND | IV | Yes |

| 1/1,000 of full dose in 1.5 h followed by 1/100 in 1.5 h, 1/10 in 6 h and the remaining dose in 24 h |

CF cystic fibrosis, ALL acute lymphatic leukemia, PPL penicilloyl-poly-l-lysine, NR not reported, ND not done

Setting

Desensitization in a child with drug allergy should be done by experienced staff with all facilities to treat medical emergencies.

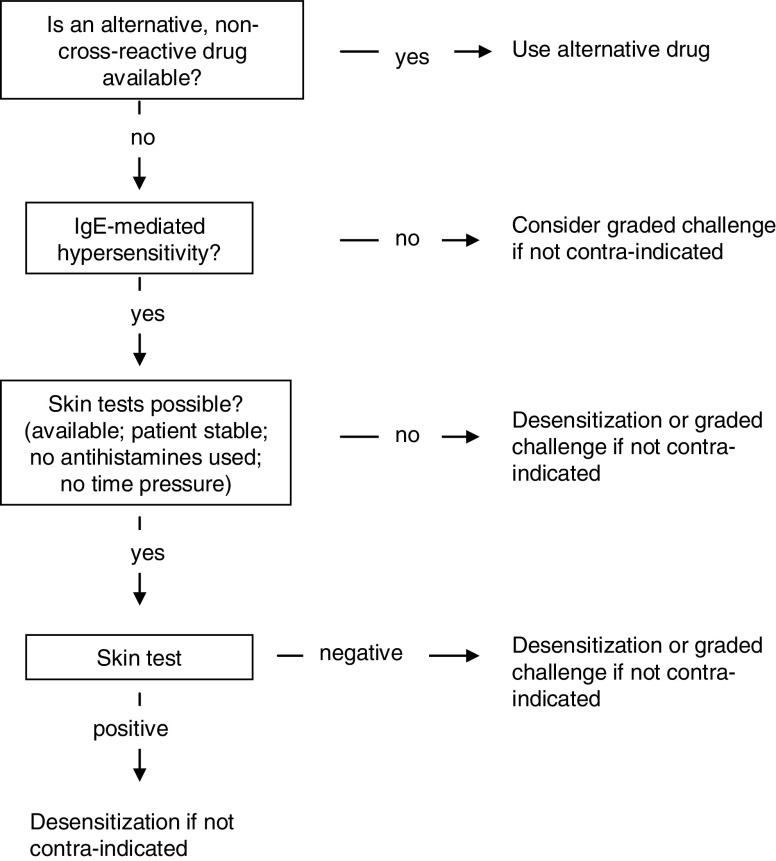

Practical proposal

This flowchart is used to decide if desensitization or graded challenge (adapted from Turvey et al. [23]) should be employed.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no financial relationship with a pharmaceutical company or organization that sponsored the research.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Aberer W, Bircher A, Romano A, et al. Drug provocation testing in the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity reactions: general considerations. Allergy. 2003;58:854–863. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bircher AJ, Ritishauser M. Oral desensitization of maculopapular exanthema from ciprofloxacin. Allergy. 1997;52:1246–1248. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1997.tb02534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouchireb K, Dodille A, Ponvert C, et al. Management and successful desensitization in methotrexate-induced anaphylaxis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52:295–297. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brockow K, Romano A, Blanca M, et al. General considerations for skin test procedures in the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity. Allergy. 2002;57:45–51. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.13027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broome CB, Schiff RI, Friedman HS. Successful desensitization to carboplatin in patients with systemic hypersensitivity reactions. Med Ped Oncol. 1996;26:105–110. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199602)26:2<105::AID-MPO7>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown LA, Goldberg ND, Shearer WT. Long-term ticarcillin desensitization by the continuous oral administration of penicillin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1982;69:51–54. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(82)90087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caldeira T, Costa V, Silva I, et al. Anaphylactoid reaction to high-dose methotrexate and re-administration after a successful desensitization. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;25:131–134. doi: 10.1080/08880010701885268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Maria C, Lebel D, Desroches A, Gauvin F. Simple intravenous antimicrobial desensitization method for pediatric patients. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2002;59:1532–1536. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/59.16.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erdem G, Staat MA, Connelly BL, Assa’ad A. Anaphylactic reaction to ciprofloxacin in a toddler: successful desensitization. Ped Inf Dis J. 1999;18:563–564. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199906000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson SGO, Bieber T, Dahl R, et al. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:832–836. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.12.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JH, Kim HB, Kim BS, Hong SJ. Rapid oral desensitization to isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol. Allergy. 2003;58:540–541. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kletzel M, Beck S, Elser J, et al. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole oral desensitization in hemophiliacs infected with human immunodeficiency virus with a history of hypersensitivity reactions. AJDC. 1991;145:1428–1429. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1991.02160120096026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreuz W, Güngör T, Lotz C, et al. “Treating through” hypersensitivity to co-trimoxazole in children with HIV infection. Lancet. 1990;336:508–509. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92059-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lafay-Cousin L, Sung L, Carret AS, et al. Carboplatin hypersensitivity reaction in pediatric patients with low-grade glioma: a Canadian Pediatric Brain Tumor consortium experience. Cancer. 2007;112:892–899. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lantner RR. Ciprofloxacin desensitization in a patient with cystic fibrosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;96:1001–1002. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(95)70240-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lavi S, Zimmerman B, Koren G, Gold R. Administration of measles, mumps and rubella virus vaccine (live) to egg-allergic children. JAMA. 1990;263:269–271. doi: 10.1001/jama.263.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA. 1998;279:1200–1205. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan M, Bowers DC, Gruchalla RS, Khan DA. Safety and efficacy of repeated monthly carboplatin desensitization. J Allerg Clin Immunol. 2004;114:974–975. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogle S, Rose MM, Tate Wildes C. Development and implementation of a carboplatin desensitization protocol for children with neurofibromatosis, type 1 and hypersensitivity reactions in an outpatient oncology clinic. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2002;19:122–126. doi: 10.1053/jpon.2002.126056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soffritti S, Ricci G, Prete A, et al. Successful desensitization to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: preliminary observations. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;40:271–272. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soyer OU, Aytac S, Tuncer A, et al. Alternative algorithm for l-asparaginase allergy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:895–899. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stark BJ, Earl HS, Gross GN, et al. Acute and chronic desensitization of penicillin-allergic patients using oral penicillin. J Allerg Clin Immunol. 1987;79:523–532. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(87)90371-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turvey SE, Cronin B, Arnold AD, Dioun AF. Antibiotic desensitization for the allergic patient: 5 years of experience and practice. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;92:426–432. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61778-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]