Abstract

Objective

Lumbar triangle hernias are rarely reported causes of low back pain. We describe the symptoms, signs, and anatomical location of 2 possible defects in the posterior abdominal wall where lumbar hernias may appear. The clinical diagnosis was challenging, and advanced imaging failed to initially uncover the conditions.

Clinical Features

We report 4 patients with spontaneous inferior lumbar triangle hernias (Petit triangle hernias) initially presenting to a primary care clinic with the primary complaint of low back pain.

Intervention and Outcomes

Thorough histories and examinations led to successful outcomes. All 4 patients were operated on to correct the defect. No recurrence has occurred.

Conclusions

Anatomical knowledge and clinical acumen led to correct diagnosis of these rare lumbar hernias. This information should help both medical and chiropractic clinicians detect these conditions, and aid in appropriate management.

Key indexing terms: Hernia, Abdominal wall, Low back pain

Introduction

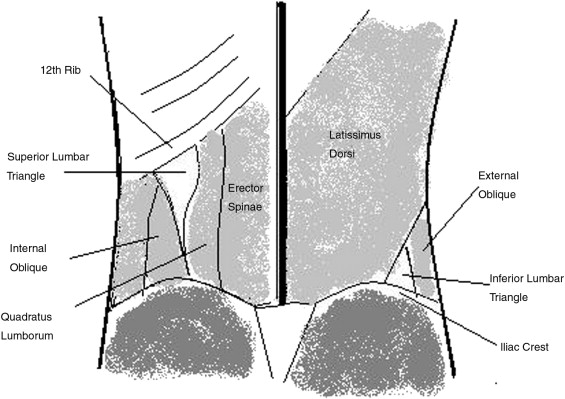

Not to be confused with herniated lumbar disks, lumbar hernias form through defects in the posterior lumbar wall. Such hernias manifest in either of 2 areas of potential weakness found within an area bordered superiorly by the 12th rib, medially by the erector spinae, and laterally by the external oblique muscle. The iliac crest borders the area inferiorly. Within the confines of this space are 2 triangles, one superior and deep, the other inferior and superficial,1 often referred to as the triangles of Grynfeltt and Petit, respectively.

Before 1980, less than 300 cases of lumbar hernias were reported in the literature. Our recent search discovered 10 articles published since 1989, reviewing 82 patients with this condition.2,3 It is important that practitioners become more aware of this condition and consider it as a differential diagnosis in appropriate cases. Timely referral is important, before complications occur.

The purpose of this article is to report on this rarely observed cause of low back pain. We report 4 cases of spontaneous inferior lumbar triangle hernias, each of which had low back pain as their presenting symptom.

Case reports

Signed consents were obtained from the patients, allowing for publication of the following deidentified clinical details.

A 60-year-old man presented with 4 to 6 weeks of left lower back soreness. Trauma was not associated with the onset of symptoms. Physical examination was remarkable for point tenderness and a palpable bulge superior to the left iliac crest. The bulge increased with forceful coughing. Radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine confirmed degenerative disk disease, but were negative for other pathology. Ultrasound was negative for retroperitoneal pathology. Surgical exploration revealed a hernia in the region of Petit triangle on the left, which was subsequently repaired, resulting in resolution of the symptoms.

A 42-year-old woman presented with 2 months of low back pain on her right side when coughing and straining. No history of trauma was recalled. Physical examination revealed significantly decreased active range of motion with flexion and extension. There were tenderness and a palpable defect superior to the right iliac crest. Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed degenerative disk disease, but was negative for other pathology. Surgical exploration revealed a hernia in the region of Petit triangle on the right, which was subsequently surgically repaired, resulting in resolution of symptoms.

A 32-year-old woman presented with a 2-week history of soreness in the right side of her low back that started after putting away boxes of Christmas decorations. No prior history of trauma was recalled. Physical examination was normal except for a tender bulge superior to the right iliac crest. Forceful coughing caused the bulge to increase in size. Lumbar radiographs and an MRI were read as normal. Surgery revealed a hernia in the region of the right Petit triangle, which was subsequently repaired, resulting in resolution of symptoms.

A 52-year-old woman presented with chronic low back pain, described as bothering her for several years but increased in the previous 3 months. No recent trauma was recalled. She had been previously diagnosed with degenerative disk disease. New imaging studies, both plain film and MRI, confirmed degenerative disk disease and several bulging lumbar disks. Recent treatments included a failed course of spinal manipulation and a series of 3 epidural steroid injections, which also failed to provide relief. She was evaluated by a neurosurgeon who recommended that a laminectomy be performed. The patient presented to her primary care physician for preoperative clearance, at which time a palpable bulge and point tenderness were found in the area of complaint. She was referred to a general surgeon who subsequently found a hernia in the region of the left Petit triangle, which was surgically repaired. Spinal surgery was avoided, and the patient remained pain free through a 4-year follow-up period.

Discussion

Description, and subsequent classification, of lumbar hernias has changed over the years. Early categories were based on the contents of the hernia. Most recently, Loukas et al4,5 classified the 2 triangles into 4 types, depending on the surface area. Dividing each triangle into 4 types is rather complex and may be most useful for radiologists and surgeons. For the practitioner of manual medicine, knowledge of general anatomical locations, causes, and relevant clinical findings of lumbar hernias will provide for easier understanding and aid in improved clinical outcomes.

Lumbar hernias may be congenital or acquired. Congenital cases are most rare and are often seen with other anomalies, such as undescended testes, bilateral renal agenesis, and lumbocostovertebral syndrome.6 Acquired lumbar hernias represent 80% of cases and are classified as either primary or secondary. Primary cases are nontraumatic and account for over half of acquired hernias.4 Twenty-five percent of lumbar hernias are considered secondary. These are related to trauma, such as motor vehicle crashes, falls, and blunt trauma, or surgeries such as renal surgery, flank incisions, and iliac bone graft harvesting.7,8 Contents of the hernias may be retroperitoneal fat, colon, small bowel, or kidney.

The superior, or Grynfeltt, triangle (Fig 1) has an inconsistent morphology and, according to Watson,9 may actually have a quadrilateral, deltoid, trapezoid, or polyhedral shape. The most consistent description in the literature is an inverted triangle, apex caudal, below the 12th rib. The medial border is the erector spinae muscle, and the internal oblique muscle forms the lateral border. Primary lesions in the superior triangle are seen more frequently than those in the lower triangle. This may be due to larger size and inherent weakness when compared with the lower triangle.10

Fig 1.

Diagram of the superior and inferior lumbar triangles.

The inferior, or Petit, triangle is smaller than the superior and is positioned apex cephalic (Fig 1). The iliac crest forms the base, with the external oblique muscle forming the lateral border and the latissimus dorsi the medial. Secondary traumatic hernias are most often found in the inferior triangle.11

Clinical findings are not always clear, but good palpation skills and a complete history will aid the clinician in making the correct diagnosis. Back and abdominal pain is common to many patients with lumbar hernias.12 It will typically be a vague soreness, with varying levels of intensity, but may be described by the patient as a specific site of tenderness. Palpation will help confirm one common clinical finding, a bulge, also often discovered by the patient, over either triangle.10,13 The bulge may become more noticeable when coughing or straining, sometimes receding when lying prone. As with the cases described above, palpation helps distinguish defects in the triangles. Challenges to accurate diagnosis include individuals who have recently lost a considerable amount of weight or the obese patient, especially if the hernia is small. Common conditions that may cause the clinician to overlook a lumbar hernia may be lumbago, lumbar radicular syndrome, or lumbar somatic dysfunction. This problem will not have radicular signs or symptoms; and the area of complaint will be lateral to the spine, sometimes a specific point of pain. A lumbar hernia may be confused with a lipoma; tumor; chronic abscess; fibroma; or, if trauma has been involved, a flank hematoma, making advanced imaging a necessity.14 Complications of lumbar hernias include incarceration, bowel obstruction, strangulation, and volvulus.15,16 Surgery is the only treatment.1 It is beyond the scope of this article to go into surgical procedures used to repair these defects.

Computerized tomography (CT) is a useful tool in differentiating lumbar hernias from other conditions. The literature is weighted toward the use of CT in the diagnosis of abdominal wall hernias. Although some authors reference the use of MRI, our literature search failed to identify any specific studies on the use of MR in diagnosing abdominal, in particular lumbar, hernias. One case report was found that supported the consideration of ultrasound in the diagnosis of lumbar hernias, due primarily to the portability of the modality, making it more accessible in some localities.17 The ability to detect defects between muscular and fascial layers, visualize herniated viscera, and differentiate a hernia from renal and other soft-tissue tumors is one of the advantages described by several authors of CT over other imaging modalities.11,15,16,18-20 Aguirre et al20 express, among other justifications, the multiplanar capabilities of multi–detector row CT as being particularly useful because of the exceptional anatomical depiction.

Conclusions

Lumbar triangle hernias are rarely reported, possibly because of a lack of clinical awareness. They may occur through defects in the inferior or superior triangles of the posterior abdominal wall. Accurate diagnosis may be a challenge. Improved understanding of the anatomy and associated clinical findings will help the practitioner of manual medicine place a timely referral if indicated. Advanced imaging, specifically MRI, failed to reveal lumbar hernias in the cases described in this report. The literature leans toward the use of CT to detect the defects associated with these conditions. The information from this case series suggests that it is important for the clinician to rely on a thorough history and physical examination, then order the appropriate diagnostic studies.

Funding sources and potential conflicts of interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

References

- 1.Armstrong O., Hamel A., Grignon B., NDoye J.M., Hamel O., Robert R. Lumbar hernia: anatomical basis and clinical aspects. Surg Radiol Anat. 2008;30:533–537. doi: 10.1007/s00276-008-0361-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavallaro G., Sadighi A., Miceli M., Burza A., Carbone G., Cavallaro A. Primary lumbar hernia repair: the open approach. Eur Surg Res. 2007;39:88–92. doi: 10.1159/000099155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu S.D., Shen K.L., Liu H.D., Chen T.W., Yu J.C. Lumbar hernia: clinical analysis of cases and review of the literature. Chir Gastroenterol. 2008;24:221–224. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loukas M., Tubbs R., El-Sedfy A., Jester A., Polepalli S., Kinsela C. The clinical anatomy of the triangle of petit. Hernia. 2007;11:441–444. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loukas M., El-Zammar D., Shoja M.M., Tubbs R.S., Zhan L., Protyniak B. The clinical anatomy of the triangle of Grynfeltt. Hernia. 2008;12:227–231. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0354-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parihar S., Bali G., Sharma S., Koul N. Congenital lumbar hernia. JK Science. 2008;10(3):144–145. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loukas M., Tubbs R.S., Shoja M. Lumbar hernia, anatomical basis and clinical aspects. Letter to the editor; Surg Radiol Anat. 2008;30:609–610. doi: 10.1007/s00276-008-0396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naidoo M., Singh B., Ramsaroop L., Satyapal K.S. Inferior lumbar triangle hernia: a case report. East Afr Med J. 2003;80(5):277–280. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v80i5.8700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson L. Hernia. 3rd ed. CV Mosby; St Louis: 1948. Lumbar hernia; p. 446. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou X., Nve J.O., Chen G. Lumbar hernia: clinical analysis of 11 cases. Hernia. 2004;8:260–263. doi: 10.1007/s10029-004-0230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hickey N.A., Ryan M.F., Hamilton P.A., Bloom C., Murphy H.P., Brenneman F. Computed tomography of traumatic abdominal wall hernia and associated deceleration injuries. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2002;53(3):153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carbonell A.M., Kercher K.W., Sigmon L., Matthews B.D., Sing R.F., Kneisl J.S. A novel technique of lumbar hernia repair using bone anchor fixation. Hernia. 2005;9:22–26. doi: 10.1007/s10029-004-0276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grauls A., Lallemand B., Krick M. The retroperitoneoscopic repair of a lumbar hernia of petit: case report and review of literature. Acta Chir Belg. 2004;104:330–334. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2004.11679566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarela A.I., Mavanur A.A., Bhaskar A.A., Soonawala Z.F., Devnani G.G., Shah H.K. Post traumatic lumbar hernia. J Postgrad Med. 1996;42:78–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aguirre D.A., Casola G., Sirlin C. Abdominal wall hernias: MDCT findings. AJR. 2004;183:681–690. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.3.1830681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker M.E., Weinerth J.L., Andriani R.T., Cohan R.H., Dunnick N.R. Lumbar hernia: diagnosis by CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:565–567. doi: 10.2214/ajr.148.3.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siffring P.A., Forrest T.S., Frick M.P. Hernias of the inferior lumbar space: diagnosis with US. Radiology. 1989;170:190. doi: 10.1148/radiology.170.1.2642342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Killeen K.L., Girard S., DeMeo J.H., Shanmuganathan K., Mirvis S.E. Using CT to diagnose traumatic lumbar hernia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:1413–1415. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.5.1741413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng S.S., Ng N.C., Liu S.Y., Lee J.F. Radiology for the surgeon: soft-tissue case 58. Can J Surg. 2006;49(2):129–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aguirre D.A., Santosa A.C., Casola G., Sirlin C.B. Abdominal wall hernias: imaging features, complications, and diagnostic pitfalls at multi-detector row CT. Radiographics. 2005;25:1501–1520. doi: 10.1148/rg.256055018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]