Abstract

Introduction

About 10-30% of people present to primary healthcare services with sore throat each year. The causative organisms of sore throat may be bacteria (most commonly Streptococcus) or viruses (typically rhinovirus), although it is difficult to distinguish bacterial from viral infections clinically.

Methods and outcomes

We conducted a systematic review and aimed to answer the following clinical questions: What are the effects of interventions to reduce symptoms of acute infective sore throat? What are the effects of interventions to prevent complications of acute infective sore throat? We searched: Medline, Embase, The Cochrane Library and other important databases up to May 2006 (BMJ Clinical Evidence reviews are updated periodically, please check our website for the most up-to-date version of this review). We included harms alerts from relevant organisations such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

Results

We found eight systematic reviews, RCTs, or observational studies that met our inclusion criteria. We performed a GRADE evaluation of the quality of evidence for interventions.

Conclusions

In this systematic review we present information relating to the effectiveness and safety of the following interventions: antibiotics, corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, paracetamol, and probiotics.

Key Points

Sore throat is an acute upper respiratory tract infection that affects the respiratory mucosa of the throat.

About 10% of people present to primary healthcare services with sore throat each year.

The causative organisms of sore throat may be bacteria (most commonly Streptococcus) or viruses (typically rhinovirus), but it is difficult to distinguish bacterial from viral infections clinically.

NSAIDs may reduce the pain of sore throat at 24 hours or less, and at 2−5 days.

NSAIDs are associated with gastrointestinal and renal adverse effects.

Paracetamol seems to effectively reduce the pain of acute infective sore throat after a single dose, or regular doses over 2 days.

Antibiotics can reduce the proportion of people with symptoms associated with sore throat at 3 days.

Reduction in symptoms seems greater for people with positive throat swabs for Streptococcus than for people with negative swabs.

Antibiotics are generally associated with adverse effects such as nausea, rash, vaginitis, and headache, and widespread usage may lead to bacterial resistance.

Antibiotics may also reduce suppurative and non-suppurative complications of group A beta haemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis, although non-suppurative complications are rare in industrialised countries.

Corticosteroids added to antibiotics may reduce the severity of pain from sore throat in children and adults compared with antibiotics alone.

Most studies used a single dose of corticosteroid.

However, data from other disorders suggest that long term use of corticosteroids is associated with serious adverse effects.

Super-colonisation with Streptococcus isolated from healthy individuals apparently resistant to infections from Streptococcus may reduce recurrence of sore throat, although there is currently no evidence to suggest it may treat symptoms of acute sore throat.

About this condition

Definition

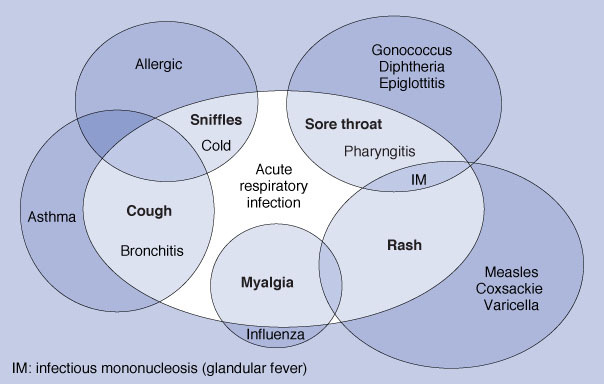

Sore throat is an acute upper respiratory tract infection that affects the respiratory mucosa of the throat. Since infections can affect any part of the mucosa, it is often arbitrary whether an acute upper respiratory tract infection is called "sore throat" ("pharyngitis" or "tonsillitis"), "common cold", "sinusitis", "otitis media", or "bronchitis" (see figure 1 ). Sometimes, all areas are affected (simultaneously or at different times) in one illness. In this review, we aim to cover people whose principal presenting symptom is sore throat. This may be associated with headache, fever, and general malaise. Suppurative complications include acute otitis media (most commonly), acute sinusitis, and peritonsillar abscess (quinsy). Non-suppurative complications include acute rheumatic fever and acute glomerulonephritis.

Figure 1.

Confusion and overlap in the classification of acute respiratory infections. IM, infectious mononucleosis (glandular fever).

Incidence/ Prevalence

There is little seasonal fluctuation in sore throat. About 10% of the Australian population present to primary healthcare services annually with an upper respiratory tract infection consisting predominantly of sore throat. This reflects about a fifth of the overall annual incidence. However, it is difficult to distinguish between the different types of upper respiratory tract infection. A Scottish mail survey found that 31% of adult respondents reported a severe sore throat in the previous year, for which 38% of these people visited a doctor.

Aetiology/ Risk factors

The causative organisms of sore throat may be bacteria (Streptococcus, most commonly group A beta haemolytic, but sometimes Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and others) or viruses (typically rhinovirus, but also coronavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, metapneumovirus, Epstein-Barr, and others). It is difficult to distinguish bacterial from viral infections clinically. Features thought to indicate Streptococcus infection are: fever greater than 38.5 °C; exudate on the tonsils; anterior neck lymphadenopathy; and absence of cough. Sore throat can be caused by processes other than primary infections, including GORD, physical or chemical irritation (e.g. from nasogastric tubes, or smoke), and occasionally hay fever. However, we consider only primary infections in this review.

Prognosis

The untreated symptoms of sore throat disappear by 3 days in about 40% of people, and untreated fevers in about 85%. By 1 week, 85% of people are symptom free. This natural history is similar in Streptococcus-positive, -negative, and untested people,

Aims of intervention

To relieve symptoms and to prevent suppurative and non-suppurative complications of sore throat.

Outcomes

Reduction in severity and duration of symptoms (sore throat pain, general malaise, headache, and fever); reduction in suppurative complications (acute otitis media, acute sinusitis, and quinsy) and non-suppurative complications (acute rheumatic fever, and acute glomerulonephritis); time off work or school; patient satisfaction; healthcare utilisation; adverse effects of treatments.

Methods

BMJ Clinical Evidence search and appraisal May 2007. The following databases were used to identify studies for this systematic review: Medline 1966 to May 2007, Embase 1980 to May 2007, and The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Clinical Trials 2007, Issue 2. Additional searches were carried out using these websites: NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) — for Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and Health Technology Assessment (HTA), Turning Research into Practice (TRIP), and National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). We also searched for retractions of studies included in the review. Abstracts of the studies retrieved from the initial search were assessed by an information specialist. Selected studies were then sent to the author for additional assessment, using pre-determined criteria to identify relevant studies. Study design criteria included: systematic reviews and RCTs. Open trials were included if the outcomes were objective (otherwise all studies described as "open", "open label", or "non-blinded" were excluded). The minimum number of individuals in each trial was 20. Size of follow-up was 80% or more. There was no minimum length of follow-up. In addition, we use a regular surveillance protocol to capture harms alerts from organisations such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), which are added to the reviews as required. We excluded RCTs that only provided data about bacteriological studies of the throat, because bacteriological cure is not a clinically useful outcome for spontaneously remitting illness. We have performed a GRADE evaluation of the quality of evidence for interventions included in this review (see table ).

Table.

GRADE evaluation of interventions for sore throat

| Important outcomes | Symptom severity, recurrence, adverse effects | ||||||||

| Number of studies (participants) | Outcome | Comparison | Type of evidence | Quality | Consistency | Directness | Effect size | GRADE | Comment |

| What are the effects of interventions to reduce symptoms of acute infective sore throat? | |||||||||

| 4 (553) | Symptom severity | Analgesics v placebo | 4 | –1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Moderate | Quality point deducted for incomplete reporting of results |

| 13 (1189) | Symptom severity | NSAIDs v placebo | 4 | –1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Moderate | Quality point deducted for incomplete reporting of results |

| 27 (12,835) | Symptom severity | Antibiotics v placebo | 4 | 0 | 0 | –1 | 0 | Moderate | Directness point deducted for narrow inclusion criteria |

| 1 (55) | Symptom severity | Corticosteroids v placebo | 4 | –1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Moderate | Quality point deducted for sparse data |

| 5 (421) | Symptom severity | Corticosteroids plus antibiotics v antibiotics | 4 | –1 | –1 | –1 | 0 | Very low | Quality point deducted for incomplete reporting of results. Consistency point deducted for conflicting results. Directness point deducted for inclusion of other drug interventions |

| 3 (448) | Recurrence rates | Probiotics v placebo | 4 | 0 | –1 | 0 | 0 | Moderate | Consistency point deducted for conflicting results |

| What are the effects of interventions to prevent complications of acute infective sore throat? | |||||||||

| 11 (3760) | Prevention of complications (AOM) | Antibiotics v placebo | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | +1 | High | Effect size point added for RR less than 0.5 |

| 16 (10,101) | Prevention of complications (acute rheumatic fever) | Antibiotics v placebo | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | +1 | High | Effect size point added for RR less than 0.5 |

| 10 (5147) | Prevention of complications (glomerulonephritis) | Antibiotics v placebo | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | High | |

| 8 (2387) | Prevention of complications (acute sinusitis) | Antibiotics v placebo | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | High | |

| 8 (2433) | Prevention of complications (peritonsillar abscess) | Antibiotics v placebo | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | +1 | High | Effect size point added for RR less than 0.5 |

Type of evidence: 4 = RCT; 2 = Observational; 1 = Non-analytical/expert opinion. Consistency: similarity of results across studies Directness: generalisability of population or outcomes Effect size: based on relative risk or odds ratio

Glossary

- High-quality evidence

Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect

- Moderate-quality evidence

Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

- Very low-quality evidence

Any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

Acute bronchitis

Acute otitis media

Acute sinusitis

Common cold

Tonsillitis

Disclaimer

The information contained in this publication is intended for medical professionals. Categories presented in Clinical Evidence indicate a judgement about the strength of the evidence available to our contributors prior to publication and the relevant importance of benefit and harms. We rely on our contributors to confirm the accuracy of the information presented and to adhere to describe accepted practices. Readers should be aware that professionals in the field may have different opinions. Because of this and regular advances in medical research we strongly recommend that readers' independently verify specified treatments and drugs including manufacturers' guidance. Also, the categories do not indicate whether a particular treatment is generally appropriate or whether it is suitable for a particular individual. Ultimately it is the readers' responsibility to make their own professional judgements, so to appropriately advise and treat their patients.To the fullest extent permitted by law, BMJ Publishing Group Limited and its editors are not responsible for any losses, injury or damage caused to any person or property (including under contract, by negligence, products liability or otherwise) whether they be direct or indirect, special, incidental or consequential, resulting from the application of the information in this publication.

References

- 1.Del Mar C, Pincus D. Incidence patterns of respiratory illness in Queensland estimated from sentinel general practice. Aust Fam Physician 1995;24:625–9,32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benediktsdottir B. Upper airway infections in preschool children – frequency and risk factors. Scand J Prim Health Care 1993;11:197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannaford PC, Simpson JA, Bisset AF, et al. The prevalence of ear, nose and throat problems in the community: results from a national cross-sectional postal survey in Scotland. Fam Pract 2005;22:227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dagnelie CF, Bartelink ML, van der Graaf Y, et al. Towards a better diagnosis of throat infections (with group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus) in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1998;48:59–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Mar CB, Glasziou PP, Spinks AB. Antibiotics for sore throat. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2007. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Search date 2006; primary sources Medline, The Cochrane Library, and hand searches of reference lists of relevant articles. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas M, Del Mar C, Glaziou P. How effective are treatments other than antibiotics for acute sore throat? Br J Gen Pract 2000;50:817–820. Search date 1999; primary sources Medline and Cochrane Controlled Trials Registry. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnett I, Schachtel B, Sanner K, et al. Onset of analgesia of a paracetamol tablet containing sodium bicarbonate: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study in adult patients with acute sore throat. Clin Ther 2006;28:1273–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francis D, Del Mar C, Thomas M, et al. Non-antibiotic treatments for sore throat (Protocol for a Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2007. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olympia RP, Khine H, Avner JR. Effectiveness of oral dexamethasone in the treatment of moderate to severe pharyngitis in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marvez-Valls EG, Ernst AA, Gray J, et al. The role of betamethasone in the treatment of acute exudative pharyngitis. Acad Emerg Med 1998;5:567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei JL, Kasperbauer JL, Weaver AL, et al. Efficacy of single-dose dexamethasone as adjuvant therapy for acute pharyngitis. Laryngoscope 2002;112:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niland ML, Bonsu BK, Nuss KE, et al. A pilot study of 1 versus 3 days of dexamethasone as add-on therapy in children with streptococcal pharyngitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2006;25:477–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Brien JF, Meade JL, Falk JL. Dexamethasone as adjuvant therapy for severe acute pharyngitis. Ann Emerg Med 1993;22:212–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roos K, Holm SE, Grahn E, et al. Alpha-streptococci as supplementary treatment of recurrent streptococcal tonsillitis: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Scand J Infect Dis 1993;25:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roos K, Holm SE, Grahn-Hakansson E, et al. Recolonization with selected alpha-streptococci for prophylaxis of recurrent streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis – a randomized placebo-controlled multicentre study. Scand J Infect Dis 1996;28:459–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falck G, Grahn-Hakansson E, Holm SE, et al. Tolerance and efficacy of interfering alpha streptococci in recurrence of streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis: a placebo-controlled study. Acta Otolaryngol 1999;119:944–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald M, Currie BJ, Carapetis JR. Acute rheumatic fever: a chink in the chain that links the heart to the throat? Lancet Infect Dis 2004;4:240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]