Abstract

L-Selectride reduction of a chiral or achiral enone followed by reaction of the resulting enolate with optically active α-alkoxy aldehydes proceeded with excellent diastereoselectivity. The resulting α,α-dimethyl-β-hydroxy ketones are inherent to a variety of biologically active natural products.

L-Selectride reduction of a chiral or achiral enone followed by reaction of the resulting enolate with optically active α-alkoxy aldehydes proceeded with excellent diastereoselectivity. The resulting α,α-dimethyl-β-hydroxy ketones are inherent to a variety of biologically active natural products.

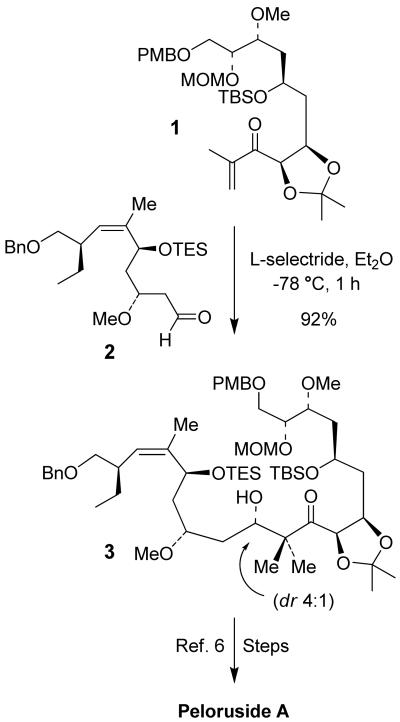

Asymmetric aldol reactions leading to the stereocontrolled generation of β-hydroxy carbonyl derivatives are among the most important reactions in organic synthesis.1 Consequently, a number of effective methodologies have been developed over the years. In a series of elegant studies, Stork and co-workers have shown that lithium-ammonia reduction of enones leads to stoichiometric generation of enolates.2 Since then, reductive aldol reactions in which conjugate reduction followed by aldol reaction of the resulting enolates led to the development of a wide variety of methodologies for the synthesis of β-hydroxy carbonyl derivatives.3 In recent years, impressive progress has been made in both catalytic4 and enantioselective5 reductive aldol processes. In the context of our enantioselective synthesis of (+)-peloruside A, we recently carried out a L-selectride mediated reductive aldol coupling of enone 1 and aldehyde 2 to provide aldol product 3 and its diastereomer as a 4:1 mixture in 92% yield at −78 °C for 1 h.6,7 The major aldolate 3 was subsequently converted to peloruside A. The overall process is quite practical and offers significant improvement over the direct aldol reaction of related ketone enolate and aldehyde reported recently.8 Of particular importance, these α,α-dimethyl β-hydroxy carbonyl derivatives are structural features of numerous bioactive natural products like epothilones,9 mycalamide A10 and peloruside A.6 Encouraged by the reasonable diastereoselectivity of the L-selectride mediated reductive aldol process, we have now examined the stereochemical outcome with a variety of chiral and achiral enones and aldehydes bearing an α- β- alkoxy stereocenter. Herein, we report the results of our investigations. Excellent levels of diastereoselectivity are attainable when the enolate from L-selectride reduction is reacted with aldehydes containing an α-chiral center.

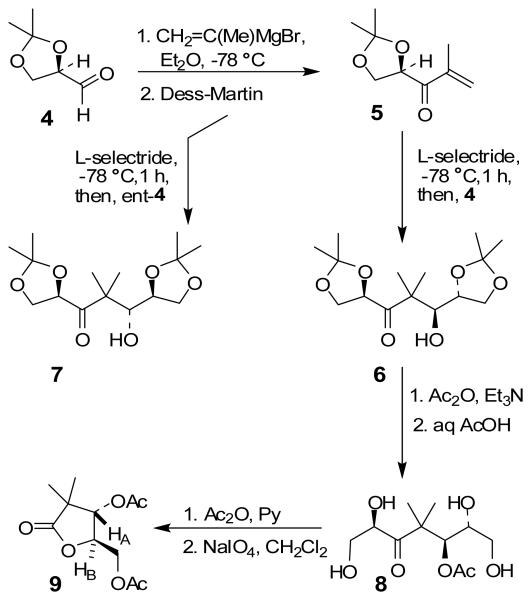

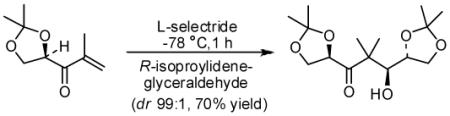

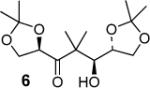

Our preliminary investigations focused on reactions with model 5 and optically active isopropylidene glyceraldehyde 4. As shown in Scheme 1, enone 5 was prepared in a two step-sequence involving: (1) reaction of isopropenyl magnesium bromide in diethyl ether followed by Dess-Martin oxidation11 of the resulting diastereomeric alcohols to enone 5 in 63% yield in 2-steps. Enone 5 was treated with 1·1 equiv of L-selectride at −78 °C for 10 min to form the corresponding lithium enolate. To the resulting enolate, 2 equiv of isopropylidene-D-glyceraldehyde in diethyl ether was added via cannula. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at −78 °C for 1 h. After this period, the reaction was quenched at −78 °C with aqueous NH4Cl solution and warmed to 23 °C. Standard workup and flash chromatography afforded aldol product 6 in 70% yield as a single anti-diastereomer (by 1H- and 13C-NMR and HPLC analysis). Since enone 5 contains a chiral center, we then examined a stereodifferentiating experiment with L-glyceraldehyde ent-4. As shown in Table 1, reaction with ent-4 also proceeded with excellent diastereoselectivity, indicating that the presence of enone chirality has no effect on antidiastereoselectivity.

Scheme 1.

Asymmetric reductive aldol reaction with chiral enone and chiral aldehydes

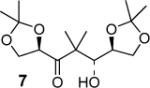

Table 1.

Reductive aldol reactions of a variety of enones and aldehydes

| enone | aldehyde | aldol product | dra(yield %)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 4 |

|

99:1 (70) |

| 5 | ent-4 |

|

99:1 (67) |

| 5 | 15 |

|

42:58 (84) |

| 5 | 16 |

|

58:42 (63) |

| 5 | 17 |

|

1:1 (50) |

| 11 | 4 |

|

99:1 (74) |

| 11 | 18 |

|

4:1c (64) |

| 11 | 17 |

|

62:38 (50) |

| 13 | 4 |

|

99:1d (72) |

| 13 | 18 |

|

99:1 (65) |

Ratios were determined by 1H and 13C-NMR analysis

Yields are after silica gel chromatography.

Ratios are from isolated yields.

HPLC analysis corresponds to 1H and 13C-NMR ratio.

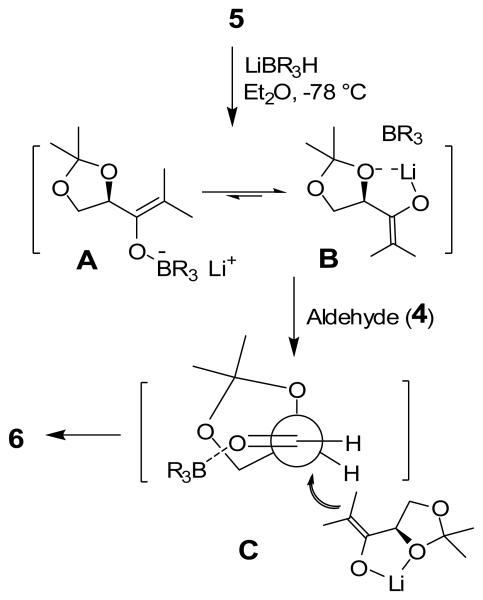

To determine the stereochemical course of the reductive aldol reaction, aldol product 6 was converted to known 3,5-diacetoxy γ-lactone 9 as follows. Protection of the hydroxyl group as an acetate followed by removal of isopropylidene groups by exposure to 40% aqueous acetic acid at 80 °C provided the corresponding tetrol 8 in 76% yield over 2 steps. Reaction of alcohol 8 with 2 equiv of acetic anhydride in pyridine provided α-hydroxy ketone 8 in 45% yield. Reaction of 8 with sodium periodate afforded γ-lactone 9 in 45% yield. The 1H NMR coupling constant (J = 5.7 Hz) between HA and HB as well as their chemical shifts were found to be consistent with an anti-isomer.12 Similarly, aldol product 7 was converted to ent-9 lactone to confirm the assignment of stereochemistry for 7. The stereochemical course of the aldol process can be explained by using a related model described by Mukaiyama and coworkers.13 As shown in Figure 2, L-selectride reduction of 5 may lead to the formation of intermediate enolates A and B and equilibrium may favor enolate B because of metal chelation. Enolate addition to aldehyde 4 may proceed through C and provide anti-alcohol 6 selectively.14

Figure 2.

Stereochemical model for aldol reactions

We have investigated diastereoselectivity associated with an aldol reaction containing a β-alkoxy stereocenter on the aldehyde component. As shown, reaction with 4 and isopropylidene butyraldehyde 15 proceeded with limited diastereoselectivity. We have further examined aldol reaction of enone 4 with aldehyde 16. Limited diastereoselectivity was observed for the β-methoxy aldehyde substrate as well. Similarly, reaction with isovaleraldehyde 17 proceeded with limited diastereoselectivity.

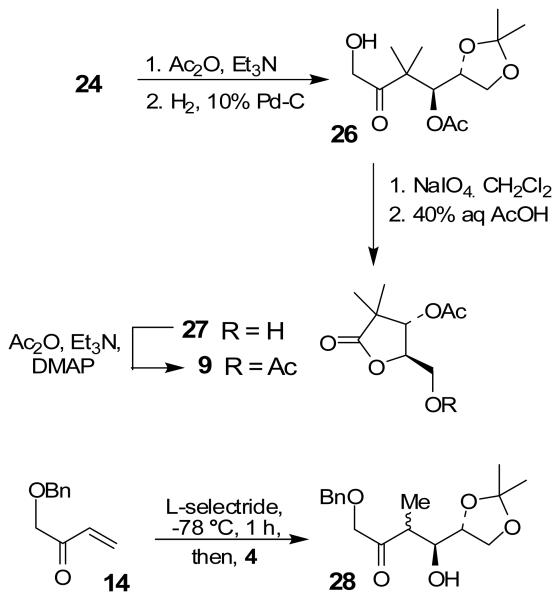

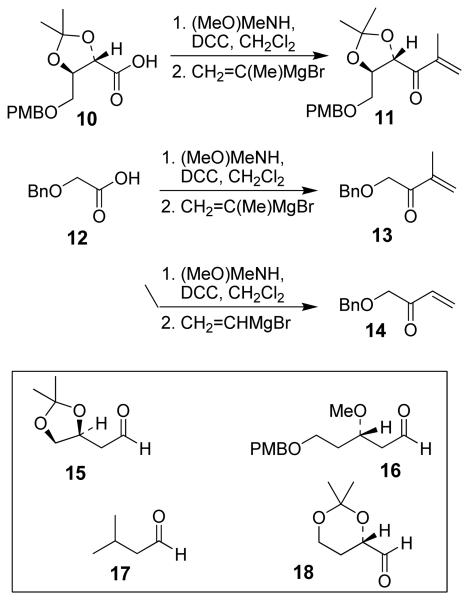

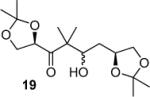

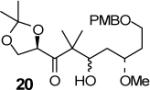

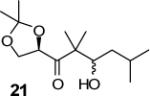

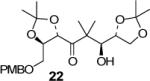

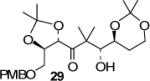

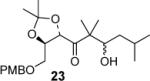

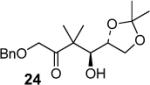

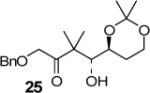

We have prepared chiral enone 11 and achiral enone 13 and examined reductive aldol reactions with aldehydes containing α-chiral centers. Enone 11 was synthesized by conversion of known15 carboxylic acid 10 to its corresponding Weinreb amide16 followed by reaction with isopropenyl Grignard reagent. Similarly, enone 13 and 14 were prepared from benzyloxyacetic acid 12. Aldol reaction of 11 with R-glyceraldehyde (4) again proceeded with excellent diastereoselectivity. As an orthogonal measure of the diastereoselectivity of this reaction, we utilized HPLC to follow this reductive aldol reaction. HPLC was able to indirectly follow the conversion of the enone to the enolate. Analysis of the crude reaction mixture after quenching with sat. NH4Cl revealed a single major peak. In order to ensure that the other diastereomer was indeed being separated by our chromatographic conditions we repeated the reaction at a higher temperature in hopes of generating the other diastereomer. After forming the enolate in > 98% yield at −78 °C, we allowed the addition of aldehyde 4 to occur at 23 °C. HPLC analysis of the crude reaction showed elevated levels of impurities. Purification of the material allowed the isolation of the diastereomer and subsequent HPLC analysis confirmed its retention time. To our delight the diastereomers of 22 were adequately resolved. Furthermore, the diastereoselectivity of the reaction was confirmed to be 99:1 at −78 °C and 92:8 at 23 °C. Interestingly, the reaction of 11 with isovaleraldehyde 17 provided a 60:40 mixture of diastereomers, indicating that the β-chiral center on the enone may be responsible for a weak directing effect. Since the α-chiral center of the aldehyde is directly responsible for the excellent observed diastereoselectivity, we have then examined an aldol reaction with an enolate derived from achiral enone 13. As can be seen, reactions with both isopropylidene glyceraldehyde 4 and isopropylidene butyraldehyde 18 provided respective anti-diastereomer 24 and 25 as a single product in very good yields.

The assignment of stereochemistry for 24 was made after its conversion to diacetoxy γ-lactone 9 as shown in Scheme 3. The free hydroxyl group in 24 was protected as its acetate. Catalytic hydrogenation over 10% Pd-C provided the hydroxyl ketone 26. Sodium periodate cleavage followed by removal of the isopropylidene group by exposure to 40% aqueous acetic acid at 80 °C afforded γ-lactone 27. It was then protected as its acetate to give γ-lactone 9. The stereochemical outcome of this aldol addition, thus indicates anti addition of the enolate to the isopropylidene glyceraldehyde. We have also investigated syn/anti aldol diastereoselectivity by reductive aldol reaction of enone 14 and aldehyde 4. However, generation of enolate and its subsequent addition to aldehyde provided a complex mixture of products. Further optimization of conditions is being investigated.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 9 and aldol reaction of 14

In conclusion, we have developed highly diastereoselective asymmetric reductive aldol methodology. Reactions involved an L-selectride reduction of chiral or achiral isopropenyl ketone followed by reaction of the resulting enolate to aldehyde containing an alkoxy stereocenter. The stereochemical course of reaction can be rationalized using a transition state model proposed by Mukaiyama and co-workers. Further exploration of this methodology is currently ongoing in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Reductive aldol reaction of 1 and 2

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of enones 10, 12 and 13

Acknowledgment

Financial support by the National Institute of Health (GM 53386) is gratefully acknowledged. We also thank Professor Mark Lipton (Purdue University) for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Mahrwald R. Modern Aldol Reactions. 1-2. Wiley-VCH; Germany: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Stork G, Darling SD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960;82:1512. [Google Scholar]; (b) Stork G, Rosen P, Golman NL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961;83:2965. [Google Scholar]; (c) Stork G, Rosen P, Goldman N, Coobms RV, Tsuji J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965;87:275. [Google Scholar]

- 3.For recent reviews on reductive aldol reactions, see: Han SB, Hassan A, Krische MJ. Synthesis. 2008;17:2669. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1067220. Garner S, Krische JJ. In: Modern Reductions. Andersson P, Munslow I, editors. Vol. 387. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2008. Nishiyama H, Shiomi T. Top. Curr. Chem. 2007;279:105.

- 4.For recent metal catalyzed reductive aldol reactions see: Shiomi T, Nishiyama H. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1651. doi: 10.1021/ol070251d. Han SB, Krische MJ. Org. Lett. 2006;8:5657. doi: 10.1021/ol0624023. Jung CK, Krische M,J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:17051. doi: 10.1021/ja066198q. Baik TG, Luis AL, Wang LC, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5112. doi: 10.1021/ja0040971. Lam HW, Joensuu PM, Murray GJ, Fordyce EAF, Prieto O, Luebbers T. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3729. doi: 10.1021/ol061329d. Doi T, Fukuyama T, Minamino S, Ryu I. Synlett. 2006;18:3013. Deschamp J, Chuzel O, Hannedouche J, Riant O. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:1292. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503791. Welle A, Diez-Gonzalez S, Tinant B, Nolan SP, Riant O. Org. Lett. 2006;8:6059. doi: 10.1021/ol062495o. Chrovian CC, Montgomery J. Org. Lett. 2007;9:537. doi: 10.1021/ol063028+. Nickel: and references cited therein.

- 5.Bee C, Han SH, Hassan A, Lida H, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:2746. doi: 10.1021/ja710862u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.West LM, Northcote PT, Battershill CN. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:445. doi: 10.1021/jo991296y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghosh A, Xu X, Kim J-H, Xu C-X. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1001. doi: 10.1021/ol703091b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu B, Zhou W-S. Org. Lett. 2004;6:71. doi: 10.1021/ol036058a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Höfle G, Bedorf N, Steinmetz H, Schomburg D, Gerth K, Reichenbach H. Angew. Chem. 1996;108:1671. [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. lnt. Ed Engl. 1996;35:1567. [Google Scholar]; Gerth K, Bedorf N, Höfle G, Irschik H, Reichenbach H. J. Antibiot. 1996;49:560. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West LM, Northcote PT, Battershill CN. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:445. doi: 10.1021/jo991296y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dess DB, Marin JC. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:4155. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dess DB, Martin JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:7277. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kita Y, Tamura O, Itoh F, Yasuda H, Kishino H, Ke YH, Tamura Y. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:554. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki K, Yuki Y, Mukaiyama T. Chem. Lett. 1981:1531. [Google Scholar]

- 14.The coordination by trialkylborane with carbonyl oxygen is presumably weak.

- 15.(a) Kigoshi H, Kita M, Ogawa S, Masahiro I, Vemura D. Org. Lett. 2003;5:957. doi: 10.1021/ol0341804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Saito S, Ishikawa T, Moriwake T. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:4375. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nahm S, Weinreb SM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:3815. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.