Abstract

Background

Interventions to teach children healthy and effective coping skills could help reduce their risk for overweight. However, few studies have examined whether an intervention that teaches coping strategies in weight management can influence children’s coping behavior and psychosocial well-being.

Objective

To examine the efficacy of an interactive, child-centered, and family-based program in promoting effective coping, behavioral health, and quality of life in Chinese American children.

Method

A randomized, controlled study of behavioral intervention in 67 Chinese American children (ages 8–10 years, normal weight and overweight) and their families. At baseline and 2, 6, and 8 months after baseline, children had anthropometric measurements and completed questionnaires related to coping skills and quality of life, and parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist.

Results

Children in the intervention group reported using more active coping strategies and having a higher quality of life in the physical and emotional health domains than did children in the control group during the 8-month study. Children’s behavioral problems did not differ between the intervention and control groups. Changes in coping and psychosocial well-being were not related to change in body mass index (BMI) in the entire group, except increased BMI is associated with decreased emotional quality of life.

Discussion

This culturally appropriate behavioral intervention was effective in promoting healthy coping and improving quality of life in Chinese American children. Its utility for both optimal weight and overweight children suggests potential application of the intervention in a broad range of populations.

Keywords: childhood obesity, Chinese-Americans, coping, quality of life

Psychological health issues associated with childhood obesity include depression, low self-esteem, social withdrawal, and poor quality of life (Anderson, Cohen, Naumova, Jacques, & Must, 2007; Csabi, Tenyi, & Molnar, 2000; Li et al., 2007). In addition, overweight children are more likely to have behavioral problems than are children of normal weight (Lumeng, Gannon, Cabral, Frank, & Zuckerman, 2003). Although some of the psychosocial problems associated with overweight may occur as a result of the weight problem, a higher level of stress in youth may put them at increased risk for becoming overweight (Nguyen-Rodriguez, Chou, Unger, & Spruijt-Metz, 2008). Thus, teaching children how to cope with stress in a more positive and effective way may lead to reduced risk for overweight.

Coping strategies such as the use of emotional eating and external eating (eating in response to food-related stimuli, regardless of the internal state of hunger and satiety) are associated with increased food intake and occur more frequently in overweight children (Braet & Van Strien, 1997; Nguyen-Michel, Unger, & Spruijt-Metz, 2007; Stauber, Petermann, Korb, Bauer, & Hampel, 2004). These findings indicate the importance of addressing psychological and behavioral outcomes in addition to relative weight change. Results of a number of studies suggest that effective interventions for weight management in children should include content targeted at dietary behavior, physical activity, and television viewing time, and incorporate training in coping skills (Golan, Kaufman, & Shahar, 2006; Stice, Shaw, & Marti, 2006; Young, Northern, Lister, Drummond, & O’Brien, 2007). However, coping strategies have been addressed in few studies having interventions for weight management.

Researchers have also found that overweight in adolescence is linked with poor physical and emotional quality of life and that overweight children report poorer quality of life than children of normal weight (Berry, Savoye, Melkus, & Grey, 2007; Wallander et al., 2009; Wille, Erhart, Petersen, & Ravens-Sieberer, 2008; Williams et al., 2005). Interventions are needed to not only improve healthy weight but also coping skills and quality of life in children. Wille and associates (2008) examined the impact of an outpatient weight management program in children. They found that perceived health, emotional well-being, and generic and disease-specific quality of life improved as a result of their intervention. Berry et al. conducted an overweight management intervention using coping skills training in obese multiethnic parents with overweight children. Results indicated that children in the intervention group (with training in coping skills) demonstrated trends toward decreased BMI, albeit not at a significant level because of the small sample size (Berry et al., 2007). However, to our knowledge no study has examined the impact of a healthy lifestyle and healthy weight program on coping skills and quality of life in Chinese-American children.

Chinese and Chinese American children use eating and watching television as common, though ineffective, coping strategies, with significant implications for weight gain (Chen & Kennedy, 2005). Chinese Americans, particularly children, are experiencing an unprecedented increase in the prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The most recent data indicate that the prevalence of overweight and obesity among Chinese Americans ages 6 to 11 years is 31% (Tarantino, 2002). Because of the difficult nature of weight control and weight management in obese adults, preventing overweight in children is a necessary strategy to combat the obesity epidemic, as studies suggest that overweight in early childhood tends to persist into middle childhood and adulthood (Magarey, Daniels, Boulton, & Cockington, 2003; Whitaker, Wright, Pepe, Seidel, & Dietz, 1997). In addition, because Chinese are the largest and fastest growing Asian subgroup in the United States, it is essential to develop culturally appropriate interventions to promote healthy coping and healthy weight in Chinese American children.

A culturally appropriate, individually tailored, child-centered, and family-focused behavioral program (the Active Balance Childhood [ABC] study) was developed to focus on healthy weight management. In the intervention, healthy lifestyles and effective coping skills were promoted to improve cardiovascular health (weight control and blood pressure) and psychosocial well-being (coping, quality of life, and behavioral health) in Chinese American children, ages 8 to 10 years. The intervention was based on social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) and focused on increasing self-efficacy of children and parents in their setting of realistic and achievable goals, providing necessary skills, and improving self-regulation in maintaining healthy bodies and healthy lifestyles.

Self-efficacy refers to people’s beliefs about their capabilities to exercise control over events that affect their lives (Bandura, 1986). It functions as an essential component in determining human affect, motivation, and action. Self-efficacy beliefs affect thought patterns that may be self-aiding or self-hindering. The major purpose of thought is to help people create the means for exercising control over time and to predict the incidence of events. To improve self-efficacy, children in the intervention program learned various skills for promoting their health and were taught to set realistic and achievable goals toward healthy lifestyles (such as to increase physical activity level by 10 minutes per day and practice relaxation techniques once a day). To improve children’s ability to self-regulate, children learned to listen to their bodies, recognize signs of hunger, and how to handle boredom and stress. Parents were taught how to provide a healthy environment and be a good role model for their child by providing healthy snacks and encouraging active family lifestyles. Positive reinforcements for improvement of the child’s behaviors were encouraged.

Only efficacy of the ABC intervention on psychosocial well-being is reported here. The effects on physical health are described elsewhere (Chen, Weiss, Heyman, & Lustig, 2009). In summary, results indicated a significant effect of the intervention in decreasing BMI, diastolic blood pressure and fat intake while increasing vegetable and fruit intake, actual physical activity, and knowledge about physical activity. The hypotheses for the psychosocial outcomes were (a) that children in the intervention group would have more effective coping strategies, better quality of life, and fewer behavioral problems than children in the control group at 2, 6, and 8 months after their baseline assessment and (b) that improvements in coping, quality of life, and behavioral health would be associated with reductions in body mass.

Method

A randomized, controlled study design was used to examine the efficacy of the ABC intervention. Children in the study completed questionnaires about coping strategies used and quality of life at baseline (T0) and 2 months (T1), 6 months (T2), and 8 months (T3) after baseline assessment. The primary caregiver completed questionnaires about parents’ demographic information, their levels of acculturation, and their child’s behavioral problems. Included were 8- to 10-year-old Chinese American children who were normal weight or overweight. Adults and children self-identified ethnicity to be Chinese or of Chinese origin, and resided in the same household. A dyad of one adult and one child was the minimum necessary for a household to participate; two adults per child were encouraged to participate. Although the two adults were encouraged to participate, only mothers in the study participated in the parent’s workshops and one child per family was enrolled in the study. Therefore, intra-family dependency on the analysis is not a concern.

The children were able to speak and read English. The children were in good health, defined as free of an acute or life-threatening disease and able to attend to activities of daily living such as going to school. Children with chronic health problems that included any dietary modifications or activity limitations (e.g., diabetes, exercise-induced asthma) were excluded. Parents were able to speak English, Mandarin, or Cantonese, and were able to read in English or Chinese and to complete questionnaires. The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco.

Study Procedure and Intervention

Participants were recruited from Chinese language programs in the San Francisco Bay area of California. Bilingual and bicultural research assistants described the study to potential children and gave them an introduction letter and a research consent form to take home to their parents. Parents who were interested in the study signed and returned the consent form, providing their names and contact information to the research team. Children and parents were informed that they could refuse to participate or withdraw from the study at any time.

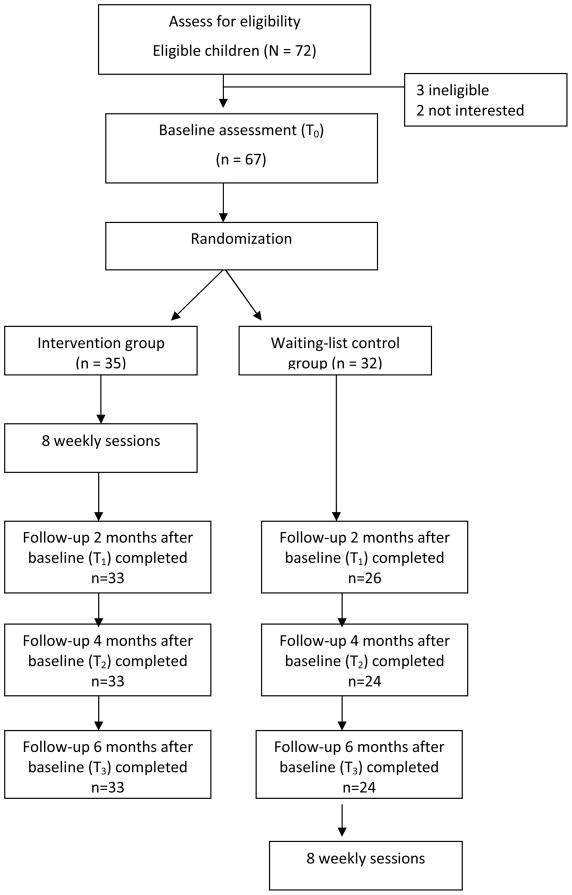

After informed consent had been obtained from parents and verbal assent obtained from children, baseline data were collected. The children and parents were assigned randomly to the intervention group or the waiting-list control group by means of a computer-generated random number assignment (Figure 1). Research assistants went to the study site and administered all of the questionnaires for children to complete. Parents completed questionnaires at home and mailed them back to the research team within 2 weeks of receiving them. Children assigned to the intervention group participated in weekly small-group sessions for 8 weeks; parents in the intervention group participated in 2 small-group workshops during that 8 weeks.

Figure 1.

Study procedure

Children and families in the control group participated in data collection activities in the same sequences as used in the intervention group. After they had completed the final follow-up assessment, children and families in the waiting-list control group also received the ABC study intervention (Figure 1).

Intervention Overview

A group of 4 to 6 families participated in a small-group session. The parents and children met separately. Children participated in a 45-minute session each week for 8 weeks, and parents participated in two 2-hour sessions facilitated by a bicultural, bilingual research assistant. The intervention program consisted of activities based on educational play to increase children’s self-efficacy in terms of diet and physical activity and to facilitate their understanding of feelings. They also received training in coping skills to improve their use of critical thinking and effective coping. Coping skills training included assertiveness, stress reduction, and problem solving strategies. Children were taught a set of skills that are important for effective coping and problem solving, including (a) identifying feelings and thoughts in response to problematic situations, (b) thinking about multiple alternative solutions to a problem, (c) evaluating the options, (d) considering the consequences of possible solutions, and (e) implementing a chosen solution to reach a specific goal (Table 1).

Table 1.

Children’s Program

| Week | Focus | Topics |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Understand how the body works and how to recognize and cope with feelings |

|

| 2 | Ability to utilize adequate problem-solving techniques and coping skills |

|

| 3 | Ability to utilize adequate relaxation techniques and develop healthy coping |

|

| 4 | Understand food and health |

|

| 5 | Ability to be make smart food choices |

|

| 6 | Ability to be improve activity level |

|

| 7 | Understand various fun activities for children and families |

|

| 8 | Understand key concepts about a healthy and happy childhood |

|

From “Efficacy of a child-centered and family-based program in promoting health weight and health behaviors in Chinese American children: A randomized controlled study,” by J. L. Chen, S. Weiss, M. B. Heyman, and R. H. Lustig, 2009, Journal of Public Health, Volume __, p. __. Reprinted with permission.

A family component (two 2-hour sessions) was incorporated into this study to provide reinforcement and social support at home for the education received during the study. The group workshops (8–10 parents) included sets of exercises to increase parents’ knowledge and skills regarding healthy food preparation, discussion of issues related to dealing with children’s eating habits and problems, and brainstorming about specific family or children’s activities to improve dietary intake, physical activity, and coping skills. Additional description of the intervention has been published elsewhere (Chen et al., 2009).

Parental Measures

Family information

The 12-item parent questionnaire includes parents’ and children’s ages, parents’ weights and heights, parents’ occupations, family income, and parents’ levels of education. The questionnaire was written at a third-grade reading level and took approximately 5 minutes to complete. The primary caregiver completed this questionnaire at baseline.

Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale (SL-ASIA)

The SL-ASIA scale, a 21-item multiple-choice questionnaire covering language (4 items), identity (4 items), friendships (4 items), behaviors (5 items), general and geographic background (3 items), and attitudes (1 item), was used to examine levels of maternal acculturation (Suinn, 1998; Suinn, Khoo, & Ahuna, 1995). Scores could range from 1.00, indicative of low acculturation or higher Asian identity, to 5.00, indicative of high acculturation or higher Western identity. Validity and a moderate to good reliability have been reported with a Cronbach’s alpha for the SL-ASIA of 0.79 to 0.91 for Chinese Americans (Suinn, 1998; Suinn et al., 1995).

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)

The CBCL, a survey including a broad range of emotional and behavior problems of children and identifying 2 major groupings of behavior problems--internalizing (fearful, inhibited, and overcontrolled behavior) and externalizing (aggressiveness, antisocial, and undercontrolled behavior)--provides a standardized measure of the behavioral problems and social competencies of children aged 2 through 18 years, as reported by their parents or others who know the child well (Achenbach, 1991). The CBCL has been the most commonly used tool in research on behavior of Chinese children and has adequate reliability and validity (Crijnen, Achenbach, & Verhulst, 1999; Liu et al., 2000; Liu et al., 1999). Test-retest reliability of 0.90, an interrater correlation of 0.89, internal consistency of 0.93 (Cronbach’s alpha) for the total scale, sensitivity of 86%, and specificity of 89% were reported for community and psychiatric samples in China (Liu et al., 1999). Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .78 to .83 in this study.

Children’s Measures

Body Mass Index (BMI)

Children’s weight and height were measured using the 214 Road Rod portable stadiometer (seca, Hamburg, Germany), which has graduations of 1/8 inch (0.1 cm), and the 840 Bella Digital Scale (seca, Hamburg, Germany), which has a gradation of 0.2 lbs (100 grams). The BMI was calculated by dividing body mass in kilograms by height in meters squared (kg/m2). The BMI was used as a measure of overweight. It has a well-established association with stature and age among children and adolescents, with validity reported in several studies (Freedman & Perry, 2000; Goran, 1998). Results indicate wide ranges of sensitivity, specificity, and misclassification. Sensitivity ranged from 29% to 88%, specificity from 94% to 100%, and predictive value from 90% to 100% (Freedman & Perry, 2000; Goran, 1998).

Coping Strategies: The Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist, Revision 1 (CCSC-R1)

This measure is a 52-item self-report inventory in which children describe their coping efforts and how they usually cope with problems. The 52 items are classified into 11 conceptually distinct coping subgroups that form four dimensions of children’s coping strategies: active coping, distraction, avoidance, and support seeking. Active coping consists of using cognitive decision making, direct problem solving, seeking understanding, and use of positive cognitive restructuring. Distraction coping consists of physical release of emotions and use of distracting actions. Avoidance coping consists of avoidant actions and cognitive avoidance. Support seeking coping includes problem-focused support and emotion-focused support. Children are asked to describe how often they usually use each behavior when they have a problem (never, sometimes, often, and most of the time). Some examples of the 52-item self-reported checklist are: you watched TV, you did some exercise, you thought about what you could do before you did something, you did something to solve the problem, and you thought about why it happened. Adequate reliability and validity have been documented (Ayers, Sandler, West, & Roosa, 1996; Sandler, Tein, & West, 1994). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .71 to .86.

Pediatric Quality of Life

This 23-item scale encompasses physical, emotional, social, and school functioning. The tool uses either a child self-report (ages 5 to 18 years) or a parallel parent proxy-report format. The child self-report form was used here; it has a 5-point response scale (0 = never a problem, 1 = almost never a problem, 2 = sometimes a problem, 3 = often a problem, 4 = almost always a problem). Examples of the 23-item scale are: it is hard for me to run, I have low energy, I feel sad or blue, and other kids tease me. A high score refers to better health-related quality of life. Reliability has ranged from 0.80 to 0.88 for child’s self-report and validity has been established (Schwimmer, Burwinkle, & Varni, 2003; Varni, Seid, & Kurtin, 2001). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .70 to .85.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated initially for demographic characteristics and all major study variables. T tests were used to assess differences in variables between intervention and control groups at baseline and between participants who completed the study and those who were lost to follow-up. Bonferroni corrections were utilized to reduce the type 1 error for multiple comparisons. The significant level for multiple t tests were set at p < .004 (.05/14). Because the intervention was delivered to small groups of 4 to 6 families, the intraclass correlation (ICC) was used to assess the magnitude of the intragroup dependency effect in the intervention group.

Multilevel regression analysis was used to test the difference in the mean change trajectories (slopes) of the intervention compared to the control groups. A significant interaction means that the linear change trajectories differ conditioned on (as a function of) group membership. When the cross-level interaction for time-by-group is significant, some authors recommend that a test of simple slopes be conducted to probe the change trajectories for each group (Bauer & Curran, 2005; Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). When a cross-level interaction is significant for a time by group longitudinal analysis, it is possible that only one group has a significant slope, that both have significant slopes either in the same or different directions (ordinal or disordinal), or that neither group has a significant slope.

To assess the efficacy of the intervention, mixed-effect models were used to estimate changes in coping strategies, quality of life, and children’s behavioral problems. An intention-to-treat strategy was utilized. Linear mixed-effects models that included functions of time and group effects were fitted to the repeated child data. With a continuous outcome, the mixed model approach to analyzing longitudinal data is a method of modeling population parameters as fixed effects while modeling an individual subject’s parameters as random effects. The modeling of individual subjects was obtained as random deviations about the population model.

Pearson correlation coefficients were used to explore how change scores for coping, quality of life, and behavioral problems might be associated with changes in BMI for the children. All analyses were performed in SPSS 17.0, with .05 set as the required level of significance.

Results

Descriptive Data

Sixty-seven children and their parents met the eligibility criteria and enrolled in the study. Thirty-five children and their families were randomized to the intervention group and 32 children and their families were in the control group. The mean age of children was 8.9 years (SD = 0.89). Twenty-nine of the children were girls, and 31 were at risk for overweight or obesity; approximately 51% of children in the intervention group and 41% of children in the control group were overweight. The mean maternal age was 41.4 years (SD = 4.37), and the mean number of years of education was 14 years (SD = 4.55). The mean paternal age was 44.25 years (SD = 5.28), and the mean number of years of education was 15.59 years (SD = 3.69). The mean acculturation was 2.38 (SD = 0.69), suggesting low acculturation. The intervention and control group did not differ significantly in baseline variables. Baseline and follow-up data are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Data

| Intervention group | Control group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 |

| Body mass index | 19.74 (3.58) | 19.48 (3.48) | 19.29 (3.45) | 19.32 (3.38) | 18.65 (2.63) | 18.14 (2.60) | 18.42 (2.69) | 18.42 (2.56) |

| Child’s Behavior Checklist | 5.21 (4.92) | 4.78 (5.00) | 3.81 (4.02) | 4.06 (4.04) | 2.22 (3.94) | 2.45 (4.08) | 1.56 (2.13) | 1.30 (2.03) |

| Internal | ||||||||

| External | 6.77 (6.12) | 6.12 (6.16) | 5.14 (5.31) | 5.45 (5.71) | 3.79 (5.10) | 4.33 (5.52) | 3.00 (3.86) | 2.71 (3.95) |

| Total | 21.47 (17.76) | 19.23 (17.84) | 16.96 (16.71) | 17.91 (16.73) | 11.84 (16.35) | 13.15 (17.31) | 8.06 (9.85) | 6.60 (9.53) |

| Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist | ||||||||

| Active coping | 2.19 (0.44) | 2.34 (0.46) | 2.40 (0.45) | 2.41 (0.79) | 2.39 (0.51) | 2.24 (0.49) | 2.29 (0.47) | 2.30 (0.53) |

| Distraction strategies coping | 2.33 (0.61) | 2.08 (0.62) | 2.08 (0.69) | 2.17 (0.64) | 2.30 (0.69) | 2.28 (0.64) | 2.34 (0.67) | 2.37 (0.57) |

| Avoidance strategies coping | 2.31 (0.45) | 2.20 (0.49) | 2.25 (0.55) | 2.30 (0.54) | 2.23 (0.52) | 2.29 (0.58) | 2.39 (0.63) | 2.45 (0.56) |

| Support seeking | 2.19 (0.69) | 2.00 (0.60) | 2.06 (0.58) | 2.12 (0.68) | 2.17 (0.54) | 2.03 (0.54) | 2.17 (0.61) | 2.16 (0.70) |

| Quality of Life | ||||||||

| Physical | 82.21 (12.90) | 85.97 (11.48) | 86.78 (11.42) | 86.50 (10.66) | 80.81 (13.67) | 80.85 (12.29) | 80.31 (11.72) | 80.74 (12.34) |

| Emotional | 64.14 (17.72) | 74.45 (18.55) | 76.97 (14.79) | 78.09 (14.51) | 71.61 (15.57) | 67.08 (17.32) | 72.55 (18.09) | 66.00 (17.06) |

| Social | 79.52 (20.10) | 79.30 (15.32) | 81.52 (15.23) | 77.94 (16.57) | 82.70 (17.67) | 81.67 (15.01) | 83.41 (15.46) | 84.25 (15.58) |

| School | 78.71 (16.38) | 80.15 (14.22) | 76.52 (18.35) | 75.44 (16.02) | 81.94 (14.06) | 78.54 (15.50) | 82.50 (16.46) | 80.75 (14.26) |

| Total | 304.59 (55.20) | 319.87 (43.96) | 321.78 (49.87) | 317.97 (48.65) | 317.06 (40.99) | 308.14 (36.44) | 318.77 (41.48) | 311.74 (36.40) |

| Psychological | 222.38 (47.83) | 233.90 (38.13) | 235.00 (41.44) | 231.47 (41.08) | 236.25 (33.19) | 227.29 (28.78) | 238.45 (33.18) | 231.00 (29.58) |

Notes. T0 = baseline, T1 = 2 months after baseline, T2 = 6 months after baseline, T3 = 8 months after baseline

Fifty-seven children and their families (85%) completed baseline and follow-up measures; 94.3% of children in the intervention group and 75% of children in the control group. No significant differences were found in baseline variables between children who provided follow-up data and children who were lost to follow-up.

The CBCL data reported in this study were within normal range and not different than normative data reported for Chinese children (Yang, Soong, Chiang, & Chen, 2000). This result suggests that the children in this study did not have significant behavioral problems based on CBCL data reported by their parents. The children in this study reported using all the coping strategies only some of the time, similar to the results of De Boo and Spiering’s (2009) study. Children also reported a similar level of quality of life compared to other studies (Pinhas-Hamiel, et al., 2006; Williams, Wake, Hesketh, Maher, & Waters, 2005), except for a lower emotional quality of life.

Intraclass Correlation

The intervention group consisted of eight small groups. As children in the intervention groups were divided into eight small groups, ICCs were calculated for each variable for the children in the intervention group. However, since the children in the control group did not have an additional grouping level, the dependency analysis is confounded by the fact that no intercept variance was found in a level 3 analysis (time by group by small groups). To describe intragroup dependency for the intervention group, ICCs were computed for each variable (Table 3). The ICCs range from 0% to 20%, indicating no correlation to a moderate level of correlation. As expected, variances were contributed mostly to between-individual differences while within-group differences account for small to moderate amount of variance.

Table 3.

Summary of Intraclass Correlations

| Variable | Parameter | Variance | ICC | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBCL Internal | Small group | 2.35 | 11.62% | .478 |

| Individual | 14.79 | 73.15% | .001 | |

| CBCL External | Small group | 2.49 | 7.5% | .618 |

| Individual | 27.07 | 81.96% | <.001 | |

| CBCL Total | Small group | 28.21 | 9.77% | .548 |

| Individual | 237 | 82.1% | < .001 | |

| CCSC: Active coping | Small group | 0 | 0% | |

| Individual | .152 | 75.2% | < .001 | |

| CCSC: Distraction strategies | Small group | .035 | 8.52% | .582 |

| Individual | .233 | 56.7% | .001 | |

| CCSC: Avoidance strategies | Small group | 0 | 0 | |

| Individual | .129 | 49.8% | .001 | |

| CCSC: Support seeking | Small group | .008 | 1.9% | .85 |

| Individual | .259 | 62.3% | .001 | |

| QOL Physical | Small group | 0 | 0 | |

| Individual | 113.171 | 82.45% | < .001 | |

| QOL Emotional | Small group | 0 | 0 | |

| Individual | 167.42 | 55.17% | .001 | |

| QOL Social | Small group | 59.48 | 20% | .225 |

| Individual | 97.947 | 33.69% | .007 | |

| QOL School | Small group | 52.865 | 19.57% | .256 |

| Individual | 116.722 | 42.21 | .003 | |

| QOL Total | Small group | 43.435 | 1.75% | .87 |

| Individual | 1742.68 | 70.15% | .001 |

Notes. ICC = intraclass correlation, CBCL = Children’s Behavior Checklist, CCSC = Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist, QOL = Pediatric Quality of Life

Multilevel Regression Analysis

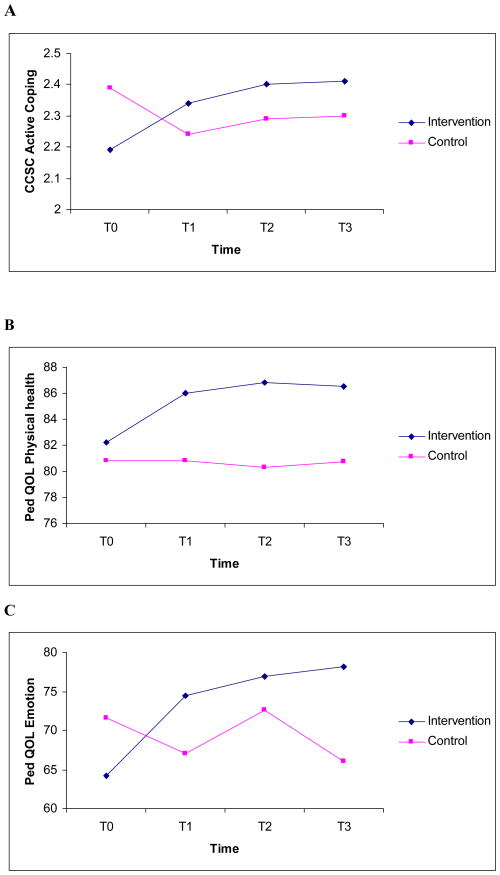

Three cross-level interactions were found to be significant for the analyses conducted for the CBCL, Coping, and Pediatric Quality of Life measures. The slopes differed between the control and intervention groups for the Active Coping scale for the CCSC, and for the Physical and Emotional scales for the Pediatric Quality of Life measure. There were no significant cross-level interactions for the CBCL subscale or total scale scores.

The cross-level interaction for the CCSC Active Coping scale was significant, indicating that the linear change trajectories differed for the two groups (t = 5.081, p < .0005). Simple linear slopes analysis revealed that there was no significant change for the control group (simple slope = −.008, t = −.496, not significant), but the change trajectory for the intervention group was significant (simple slope = −.096, t = 7.45, p < .0005). A plot of the estimated slopes showed that active coping was predicted to increase significantly for the intervention group, but slightly decreased for the control group (Figure 2). The same pattern of change was observed for the Physical and Emotional scales for the Pediatric Quality of Life measure. In both cases, the interaction was significant (Physical, t = 3.545, p = .001; Emotional, t = 3.859, p < .0005), and the simple slopes for the intervention group were significant and positive (Physical, t = 4.605, p < .0005; Emotional, t = 5.715, p < .0005), while the slopes for the control group were not significant (Physical, t = −.835, not significant; Emotional, t = −.361, not significant).

Figure 2.

Scores for (A) Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist, active coping; (B) Pediatric Quality of Life, physical health; and (C) Pediatric Quality of Life, emotional health

Hypothesis Testing

Results of the mixed model analysis indicate that, in contrast to the control group, children in the intervention group increased their use of active coping strategies and developed a better quality of life related to their physical and emotional health over the course of the 8-month study. No difference was found in children’s behavioral problems between the intervention group and the control group (Table 4 and Figure 2). Changes in coping and psychosocial well-being were not related to any change in BMI in children, except for emotional quality of life where increased BMI is associated with decreased emotional quality of life over the course of the 8-month study (r = −.35, p = .012).

Table 4.

Summary of Mixed-Model Analysis

| Outcomes | Parameter | Effect estimate | 95% confidence interval | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children’s Behavior Checklist | Healthy Weight and Healthy Lifestyle Program 36 | |||

| Internal | Time* | −0.45 | −0.84 – −0.05 | .03 |

| Group* | 2.74 | 0.77 – 4.72 | .01 | |

| Time x Group | 0.02 | −0.47 – 0.52 | .93 | |

| External | Time* | −0.74 | −1.14 – −0.35 | .01 |

| Group | 2.54 | −0.11 – 5.18 | .06 | |

| Time x Group | 0.22 | −0.27 – 0.71 | .37 | |

| Total | Time* | −2.45 | −3.65 – −1.24 | .01 |

| Group | 8.02 | 0.03 – 16.01 | .05 | |

| Time x Group | 1.07 | −0.43 – 2.58 | .16 | |

| Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist | ||||

| Active copinga | Time | −0.01 | −0.03 – 0.01 | .64 |

| Group | −0.13 | −0.44 – 0.09 | .25 | |

| Time x Group* | 0.10 | 0.06 – 0.14 | .01 | |

| Distraction strategies coping | Time | 0.02 | −0.05 – 0.09 | .67 |

| Group | −0.08 | −0.38 – 0.22 | .59 | |

| Time x Group | −0.06 | −0.15 – 0.03 | .19 | |

| Avoidance strategies coping | Time* | 0.07 | 0.01 – 0.14 | .02 |

| Group | 0.03 | −0.22 – 0.28 | .80 | |

| Time x Group | −0.08 | −0.16 – 0.01 | .06 | |

| Support-seeking strategies | Time* | 0.08 | 0.01 – 0.14 | .02 |

| Group | 0.01 | −0.29 – 0.31 | .95 | |

| Time x Group | −0.08 | −0.19 – 0.02 | .07 | |

| Pediatric Quality of Life | ||||

| Physicala | Time | −0.35 | −1.10 – 0.40 | .36 |

| Group | 2.09 | −3.90 – 8.08 | .49 | |

| Time x Group* | 1.82 | 0.87 – 2.77 | .01 | |

| Emotionala | Time | −0.36 | −2.33 – 1.61 | .72 |

| Group | −4.78 | −12.60 – 3.03 | .23 | |

| Time x Group* | 4.94 | 2.41 – 7.46 | .01 | |

| Social | Time | 1.22 | −0.85 – 3.29 | .25 |

| Group | −2.46 | −10.03 – 5.11 | .52 | |

| Time x Group | −1.35 | −4.01 – 1.31 | .32 | |

| School | Time | 0.27 | −1.50 – 2.05 | .76 |

| Group | −1.42 | −8.63 – 5.79 | .70 | |

| Time x Group | −1.46 | −3.73 – 0.82 | .21 | |

| Total | Time | 0.07 | −6.02 – 6.16 | .98 |

| Group | −14.56 | −38.73 – 9.61 | .24 | |

| Time x Group | 2.00 | −5.81 – 9.81 | .61 | |

Notes.

p < .05

Significant difference between the intervention and control group over the study time

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the efficacy of a culturally appropriate, child-based, and family-centered intervention to incorporate training in coping skills to improve healthy weight and psychosocial well-being in Chinese American children. Compared with children randomly assigned to the control group, children in the intervention group used significantly more active coping strategies and reported higher physical and emotional quality of life.

The results suggest that incorporating coping skills training in healthy weight management can be successful in improving active coping in children. Based on previous research in which it was found that Chinese and Chinese American children use eating and watching television as common, but ineffective, coping strategies (Chen & Kennedy, 2005), it seems advisable to include coping skills for overweight prevention and management. This could involve assessing how each child copes with stress, identifying healthy coping strategies, and teaching children more effective problem-solving and coping skills.

In addition to improved coping, children in the intervention group reported higher levels of quality of life in the physical and emotional health domains. It is possible that as children improve their coping and their relative weight, they feel healthier and better about themselves. The study intervention and coping skills training emphasized the importance of recognizing one’s own feelings and identified effective healthy coping strategies that the child can use to deal with stress (such as being active through dance or listening to music). Children learned to cope with stress by using more problem-focused coping, identifying solutions to problems, and doing something to change the situation. As children are able to master these coping skills, they are more likely to feel better about themselves both physically and psychologically, thus improving their quality of life.

The results suggest that increased BMI is associated with decreased emotional quality of life in Chinese-American children. Thus, including coping skills training in a weight management program can improve quality of life in children. Changes were not found in coping or other domains of psychosocial well-being associated with reduced body mass. This could be related to the short period of time over which we assessed these potential changes. It may take longer for weight to be influenced by new coping skills, improved physical quality of life, or more optimal behavioral health. In addition, a larger sample and a more sophisticated analytic technique (e.g., path analysis) may be needed to demonstrate any link between these variables.

The data (from the CBCL, CCSC, and QOL) are similar to what is found in existing literature, suggesting that Chinese American children have a lower level of behavioral problems, used various types of coping strategies, and reported similar levels of quality of life. In addition, a small to moderate degree of ICC was found in the intervention groups. Despite the small to moderate ICC, most of the study outcome variances were explained by the within-individual changes. Similar to the ICC results, the multilevel regression analysis suggests that children in the intervention group improved their use of active coping strategies and level of quality of life in physical and emotional domains while levels children in the control group did not change. However, children in both groups decreased their internal and external behavioral problems as reported by their parents. In future research, the mechanism related to the decrease in behavioral problems in this population can be explored.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has declared obesity prevention to be a top research priority. Identifying culturally appropriate and effective interventions to promote healthy behaviors and healthy weight in children is critical. This intervention study provides a first insight into an intervention to promote healthy coping and healthy weight management in Chinese American children.

Since a convenience sample was used, generalizability of the results may be limited, and it is possible that the children and families who participated in this study were more aware of health issues related to obesity and had healthier coping than did those who declined to participate. Further, in this study, only the short-term efficacy of the intervention was assessed. Future studies would have wider applicability if more diverse and larger samples were included to examine the impact of this type of intervention over longer periods. In addition, future research needs to examine the mechanism in which positive coping strategies influence children’s health, health behaviors, and types of strategies and interventions to improve their overweight-related coping strategies.

Despite the study’s limitations, the results provide new information on the use of coping skills training in improving coping and psychosocial well-being as related to the prevention of childhood obesity in this fast-growing minority population in the US. This culturally appropriate intervention is feasible and effective for improving coping and quality of life in Chinese American children.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: This publication was made possible by grant number KL2 RR024130 to Jyu-Lin Chen from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, Chinese Community Health Care Association community grants, and in part by NIH grant DK060617 to Melvin B. Heyman.

Contributor Information

Jyu-Lin Chen, Department of Family Health Care Nursing, School of Nursing, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California.

Sandra J. Weiss, Department of Community Health Systems, School of Nursing, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California.

Melvin B. Heyman, Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California.

Bruce Cooper, School of Nursing, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California.

Robert H. Lustig, Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California.

References

- Achenbach T. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4 – 18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SE, Cohen P, Naumova EN, Jacques PF, Must A. Adolescent obesity and risk for subsequent major depressive disorder and anxiety disorder: Prospective evidence. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69(8):740–747. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815580b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers TS, Sandler IN, West SG, Roosa MW. A dispositional and situational assessment of children’s coping: Testing alternative models of coping. Journal of Personality. 1996;64(4):923–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Curran PJ. Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: Inferential and graphical techniques. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2005;40(3):373–400. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4003_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry D, Savoye M, Melkus G, Grey M. An intervention for multiethnic obese parents and overweight children. Applied Nursing Research. 2007;20(2):63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braet C, Van Strien T. Assessment of emotional, externally induced and restrained eating behaviour in nine to twelve-year-old obese and non-obese children. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35(9):863–873. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JL, Kennedy C. Cultural variations in children’s coping behaviour, TV viewing time, and family functioning. International Nursing Review. 2005;52(3):186–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2005.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JL, Weiss S, Heyman MB, Lustig RH. Efficacy of a child-centred and family-based program in promoting healthy weight and healthy behaviors in Chinese American children: A randomized controlled study. Journal of Public Health. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp105. in press. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crijnen AA, Achenbach TM, Verhulst FC. Problems reported by parents of children in multiple cultures: The Child Behavior Checklist syndrome constructs. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(4):569–574. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csabi G, Tenyi T, Molnar D. Depressive symptoms among obese children. Eating and Weight Disorders. 2000;5(1):43–45. doi: 10.1007/BF03353437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boo GM, Spiering M. Pre-adolescent gender differences in associations between temperament, coping, and mood. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2009 doi: 10.1002/cpp.664. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman DS, Perry G. Body composition and health status among children and adolescents. Preventive Medicine. 2000;31(2):S34–S53. [Google Scholar]

- Golan M, Kaufman V, Shahar DR. Childhood obesity treatment: Targeting parents exclusively v. parents and children. The British Journal of Nutrition. 2006;95(5):1008–1015. doi: 10.1079/bjn20061757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goran MI. Measurement issues related to studies of childhood obesity: Assessment of body composition, body fat distribution, physical activity, and food intake. Pediatrics. 1998;101(3 Pt 2):505–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YP, Ma GS, Schouten EG, Hu XQ, Cui ZH, Wang D, et al. Report on childhood obesity in China (5) body weight, body dissatisfaction, and depression symptoms of Chinese children aged 9–10 years. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences. 2007;20(1):11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Guo C, Okawa M, Zhai J, Li Y, Uchiyama M, et al. Behavioral and emotional problems in Chinese children of divorced parents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(7):896–903. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200007000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Kurita H, Guo C, Miyake Y, Ze J, Cao H. Prevalence and risk factors of behavioral and emotional problems among Chinese children aged 6 through 11 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(6):708–715. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumeng JC, Gannon K, Cabral HJ, Frank DA, Zuckerman B. Association between clinically meaningful behavior problems and overweight in children. Pediatrics. 2003;112(5):1138–1145. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magarey AM, Daniels LA, Boulton TJ, Cockington RA. Predicting obesity in early adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 2003;27(4):505–513. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Michel ST, Unger JB, Spruijt-Metz D. Dietary correlates of emotional eating in adolescence. Appetite. 2007;49(2):494–499. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Rodriguez ST, Chou CP, Unger JB, Spruijt-Metz D. BMI as a moderator of perceived stress and emotional eating in adolescents. Eating Behaviors. 2008;9(2):238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinhas-Hamiel O, Singer S, Pilpel N, Fradkin A, Modan D, Reichman B. Health-related quality of life among children and adolescents: Associations with obesity. International Journal of Obesity. 2006;30(2):267–272. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31(4):437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Tein JY, West SG. Coping, stress, and the psychological symptoms of children of divorce: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Child Development. 1994;65(6):1744–1763. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwimmer JB, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life of severely obese children and adolescents. JAMA. 2003;289(14):1813–1819. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauber T, Petermann F, Korb U, Bauer A, Hampel P. Adipositas und Stressverarbeitung im Kindesalter [Obesity and coping in childhood] Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie. 2004;53(3):182–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Shaw H, Marti CN. A meta-analytic review of obesity prevention programs for children and adolescents: The skinny on interventions that work. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(5):667–691. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suinn RM. Measurement of Acculturation of Asian Americans. Asian American and Pacific Islander Journal of Health. 1998;6(1):7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suinn RM, Khoo G, Ahuna C. The Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity acculturation scale: Cross-cultural information. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 1995;23(3):139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Tarantino R. Addressing childhood and adolescent overweight. Paper presented at the NICOS meeting of the Chinese Health Coalition; San Francisco, CA. 2002. Sep, [Google Scholar]

- Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Medical Care. 2001;39(8):800–812. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallander JL, Taylor WC, Grunbaum JA, Franklin FA, Harrison GG, Kelder SH, et al. Weight status, quality of life, and self-concept in African American, Hispanic, and White fifth-grade children. Obesity. 2009;17(7):1363–1368. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337(13):869–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wille N, Erhart M, Petersen C, Ravens-Sieberer U. The impact of overweight and obesity on health-related quality of life in childhood--results from an intervention study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Wake M, Hesketh K, Maher E, Waters E. Health-related quality of life of overweight and obese children. JAMA. 2005;293(1):70–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HJ, Soong WT, Chiang CN, Chen WJ. Competence and behavioral/emotional problems among Taiwanese adolescents as reported by parents and teachers. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(2):232–239. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200002000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young KM, Northern JJ, Lister KM, Drummond JA, O’Brien WH. A meta-analysis of family-behavioral weight-loss treatments for children. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27(2):240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]