Abstract

Picky eating is a common disorder during childhood often causing considerable parental anxiety. This study examined the incidence, point prevalence, persistence and characteristics of picky eating in a prospective study of 120 children and their parents followed from 2 to 11 years. At any given age between 13% and 22% of the children were reported to be picky eaters. Incidence declined over time whereas point prevalence increased indicating that picky eating is often a chronic problem with 40% having a duration of more than 2-years. Those with longer duration differed from those with short duration having more strong likes and dislikes of food and not accepting new foods. Parents of picky eaters were more likely to report that their children consumed a limited variety of foods, required food prepared in specific ways, expressed stronger likes and dislikes for food, and threw tantrums when denied foods. They were also more likely to report struggles over feeding, preparing special meals, and commenting on their child’s eating. Hence, picky eating is a prevalent concern of parents and may remain so through childhood. It appears to be a relatively stable trait reflecting an individual eating style. However no significant effects on growth were observed.

Keywords: Picky eating, Feeding Behavior, Food Preferences, Longitudinal Study

1. Introduction

Picky eating is a relatively common problem during childhood ranging from 8% to 50% of children in different samples and is characterized by the toddler or child eating a limited amount of food, restricting intake particularly of vegetables, being unwilling to try new foods, and having strong food preferences often leading parents to provide their child a meal different from the rest of the family (Carruth et al., 1998; Carruth et al., 2004; Dubois et al., 2007a; Dubois et al., 2007b; Jacobi et al., 2008; Lewinsohn et al., 2005; Marchi & Cohen, 1990). Picky eating may cause parents considerable concern leading to physician visits and may cause conflict between parents regarding the handling of their child’s eating behavior (Jacobi et al., 2003). One reason for variation in the frequencies of picky eating between studies is that studies differ in the ages of children included and in the duration of picky eating required for a case, with the proportion decreasing the longer the required interval. For example, Dubois et al. (2007a) in a study from the Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development in which 1498 children aged 2.5 to 4 years were assessed at three intervals found that 30% were picky eaters at some time during the 18-months of the study although only 5.5% were picky eaters across all three intervals. A further reason for variation is the somewhat different definitions and assessments of picky eating. As a recent review noted “assessment of picky eating is in its infancy” (Dovey et al., 2008).

Although the long-term health effects of picky eating are unclear there is evidence in early childhood that picky eaters weigh less than non-picky eaters. Dubois found that picky eaters ate fewer calories and were twice as likely to be underweight as non-picky eaters (Dubois et al., 2007a; Dubois et al., 2007b). A previous study of 135 children aged 5 years from the Stanford Infant Growth Study found that picky eaters consumed fewer calories than non-picky children and showed a less vigorous sucking style as an infant, suggesting that picky eating has trait-like characteristics (Jacobi et al., 2003). In a further study of over 800 families interviewed on three occasions from 1–10 years, 9–18 years and 11–21 years picky eating was found to be a risk factor for the development of symptoms of anorexia nervosa (Marchi & Cohen, 1990). Finally, a German study of 426 children 8 to 12 years of age found that picky eaters were more likely to exhibit problem behaviors than non-picky eaters (Jacobi et al., 2008). Hence, there is evidence in childhood that picky eaters are likely to consume fewer calories and to weigh less, and in later childhood to demonstrate behavior problems and in adolescence symptoms of anorexia nervosa.

The longer-term course of picky eating is unclear. During early childhood the rates of picky eating remain stable over a two year period (Dubois et al., 2007a) and picky eating has a similar prevalence of 18% and similar characteristics in later childhood (Jacobi et al., 2008) as compared with studies of early childhood. The only prospective study found fairly high correlations and similar prevalences between childhood and adolescent picky eating (Marchi & Cohen, 1990) although this study did not investigate stability of the syndrome. Hence, the studies to date suggest that a subset of those with picky eating tends to persist over time with similar symptoms, particularly during early and later childhood. To further investigate the course and persistence of picky eating during childhood we prospectively examined a cohort of children assessed from 2 to 11 years of age to determine the incidence, point prevalence, persistence, differences between those who persist and those who do not, differences between early and late onset cases, and characteristics of picky eating over time. Hence, this study extends our previous findings from a similar cohort from the Stanford Infant Growth study in which children were followed from 2 to 5 years of age (Jacobi et al., 2003).

2. Method

2.1 Participants

Two hundred and sixteen newborns and their parents were recruited from three hospitals in the San Francisco Bay area to participate in the Stanford Infant Growth Study. Recruitment began in 1/1990 and ended in 3/1991 and the study was completed in 12/2002. This study was approved by the Stanford University Committee for the protection of human subjects. Recruitment of the original cohort was described in detail in previous publications (Agras et al., 2007; Agras et al., 2004). Potential participants were identified and assessed for eligibility shortly after birth from hospital records. Infants born >37 weeks gestational age, with Apgar scores of at least 7 at both 1 and 5 minutes after delivery, with no congenital abnormalities, who had not experienced illness during their newborn hospitalization were considered eligible to enroll. Of the 216 infants and their parents initially enrolled in the study, 120 (61 males and 59 females) who completed all assessments from 2 to 11 years participated in this study. Assessments were at yearly intervals from 2–7 years and then at 9.5 and 11.0 years.

2.2 Measures

In addition to demographic information obtained from a parent the following measures were obtained:

2.2.1 Picky eating

At each assessment a parent (usually mother) was asked “ Is your child a picky eater?” with 5 response choices of (1) Never, (2) Rarely, (3) Sometimes (4) Often, (5) Always. To be considered as a picky eater at a given age, a score of at least “often” had to be endorsed. This single question was chosen based on observations from two previous studies (Carruth et al., 2004; Jacobi et al., 2003). The first study (Carruth et al., 2004) used a random National sample of 3022 children aged 4–24 months in the Feeding Infants and Toddler Study (FITS). Participant parents were asked “ Do you consider your child to be a picky eater?” in several response categories from “very picky” to “not picky”. Those characterized as “very picky” and “somewhat picky” formed the study group of picky eaters. This categorization was compared with a 24-hour dietary recall that demonstrated differences in dietary intake between picky and non-picky eaters. Picky eaters consumed significantly fewer calories than non-picky eaters at 11-months of age. The second study involved 135 children 2 to 5 years of age (Jacobi et al., 2003). Picky eating was defined in a similar manner to the FITS study, i.e. “Is your child a picky eater” with several response categories. Those responding “often” and “always” were categorized as picky eaters and compared with non-picky eaters in a laboratory meal and a standardized home feeding. Picky eaters ate significantly fewer foods/day than non-picky eaters and picky girls significantly decreased their caloric intake between 3.5 and 5.5 years of age on the home feeding. No differences were found for eating style on the laboratory meal.

To evaluate incidence, cases that had not previously been defined as picky were included as new cases at each assessment. Duration was measured as the number of years where picky eating was endorsed with 1 or 2 years defined as short duration and 3 or more years as long duration. Early onset of picky eating was defined as onset before 4 years of age, later onset was from 4 years on.

2.2.2 Anthropometrics

Children’s height and weight for this study were assessed annually using a balance beam scale from 2–7 years, and at 9.5 and 11-years.

2.2.3 Child and parent feeding behaviors

Stanford Feeding Questionnaire. This instrument was used at each assessment. These questions assessed behaviors such as eating a limited variety of foods, having foods prepared in specific ways, etc., on a 5 point Likert scale (See Table 2). The higher three points “more than half the time” to “always” were combined in the “Yes” category to facilitate comparison with the previous study from 3 to 5 years of age. The same questionnaire assessed various parent feeding behaviors likely to be associated with picky eating such as struggles with their child over eating too little, arguing with spouse about their child’s eating, etc. (See Table 3).

Table 2.

Parent reported child behaviors related to picky eating at age 11

| MALES | FEMALES | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Not Picky n=45 |

Picky n=16 |

Not Picky n=49 |

Picky n=10 |

Not Picky n=94 |

Picky N=26 |

|

| Limited variety of foods ^^^ |

14% | 94% | 14% | 90% | 14% | 92% |

| Food prepared in specific ways ^^^ |

13% | 63% | 18% | 67% | 16% | 64% |

| Accepts new foods readily^^^ |

60% | 0% | 65% | 0% | 63% | 0% |

| Has strong likes^^ | 62% | 94% | 67% | 90% | 65% | 92% |

| Has strong dislikes ^^^ | 44% | 100% | 49% | 100% | 47% | 100% |

| Is a slow eater * | 20% | 33% | 14% | 0% | 17% | 20% |

| Is a fast eater | 11% | 20% | 16% | 0% | 14% | 12% |

| Child has tantrums when parents Say no to food ^ # |

4% | 37% | 8% | 11% | 6% | 28% |

Gender *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001

Pickiness ^p<.05, ^^p<.01, ^^^p<.001

Interaction #p<.05, ##p<.01, ###p<.001

Table 3.

Parent reports of their behaviors relevant to their child’s eating at 11 years

| MALES | FEMALES | TOTAL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Picky n=45 |

Picky n=16 |

Not Picky N=49 |

Picky n=10 |

Not Picky n=94 |

Picky n=26 |

|

| Frequent struggles over food^^^ |

11% | 56% | 12% | 70% | 12% | 62% |

| Struggle because child eats too little |

2% | 13% | 4% | 10% | 3% | 12% |

| Struggle because s/he eats too much |

2% | 6% | 4% | 10% | 3% | 8% |

| Struggle over the types of food s/he prefers^^^ |

7% | 56% | 8% | 80% | 7% | 65% |

| Argue with spouse about child’s eating |

16% | 44% | 19% | 50% | 17% | 46% |

| Limit sweets | 82% | 88% | 88% | 70% | 85% | 81% |

| Limit non-sweets^ | 35% | 18% | 30% | 10% | 33% | 15% |

| Verbally encourage if child doesn’t eat |

62% | 81% | 80% | 80% | 71% | 81% |

| Offer reward if child doesn’t eat |

0% | 19% | 4% | 0% | 2% | 12% |

| Threaten if child doesn’t eat |

4% | 6% | 2% | 10% | 3% | 8% |

| Do nothing if child doesn’t eat * |

44% | 31% | 41% | 30% | 43% | 31% |

| Prepare separate meal for child ^^^ |

11% | 56% | 24% | 60% | 18% | 58% |

Gender *p<.05 **p<.01 *** p<.001

Pickiness^p<.05 ^^p<.01 ^^^p<.001

Interaction #p<.05 ##p<.01 ### p<.001

Child Feeding Questionnaire. This questionnaire was developed to assess parental perceptions and concerns about obesity, and parental use of child feeding practices. Parent food restriction and pressure to eat were used in the present study (Birch et al., 2001).

Parental Authority Questionnaire. This questionnaire assesses parental disciplinary practices with three scales: Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive (Buri, 1989).

2.2.4 Statistical analysis

Cross-sectional analysis

Two-way ANOVA were used to ascertain differences between picky and non-picky eaters at age 11 years with gender, picky eating status at 11 years and the interaction as independent variables. Specific child behaviors and parental responses were used as dependent measures.

Longitudinal analysis

Two way ANOVA were used to compare early and late onset and short and long duration with gender as the independent measure. The same 11 year old child behaviors and parental responses were used as dependent measures.

3. Results

There were no significant differences between the 120 participants included in this sample and the original cohort on any of the demographic variables listed in Table 1. Of the 120 participants, 20 (17%) were minorities: 12 Asian, 5 Hispanic, 2 African Americans, and 1 American Indian. The majority had completed college or graduate school. Twenty-three percent of fathers and 16% of mothers had been born outside the United States.

Table 1.

Demographics of the sample at entry to the study (N = 120)

| Gender | |

| Male | 61 (51%) |

| Female | 59 (49%) |

| BMI- 1 month | 14.4 (1.3) |

| Minority | 20 (17%) |

| Father’s BMI | 25.5 (3.4) |

| Mother’s BMI | 24.1 (4.4) |

| Father’s Age | 35.4 (4.5) |

| Mother’s Age | 33.0 (4.0) |

| Father’s education | |

| High school | 7 (6%) |

| College | 56 (47%) |

| Graduate school | 57 (47%) |

| Mother’s education | |

| High school | 3 (3%) |

| College | 65 (54%) |

| Graduate school | 52 (43%) |

| Father born outside USA | 28 (23%) |

| Mother born outside USA | 19 (16%) |

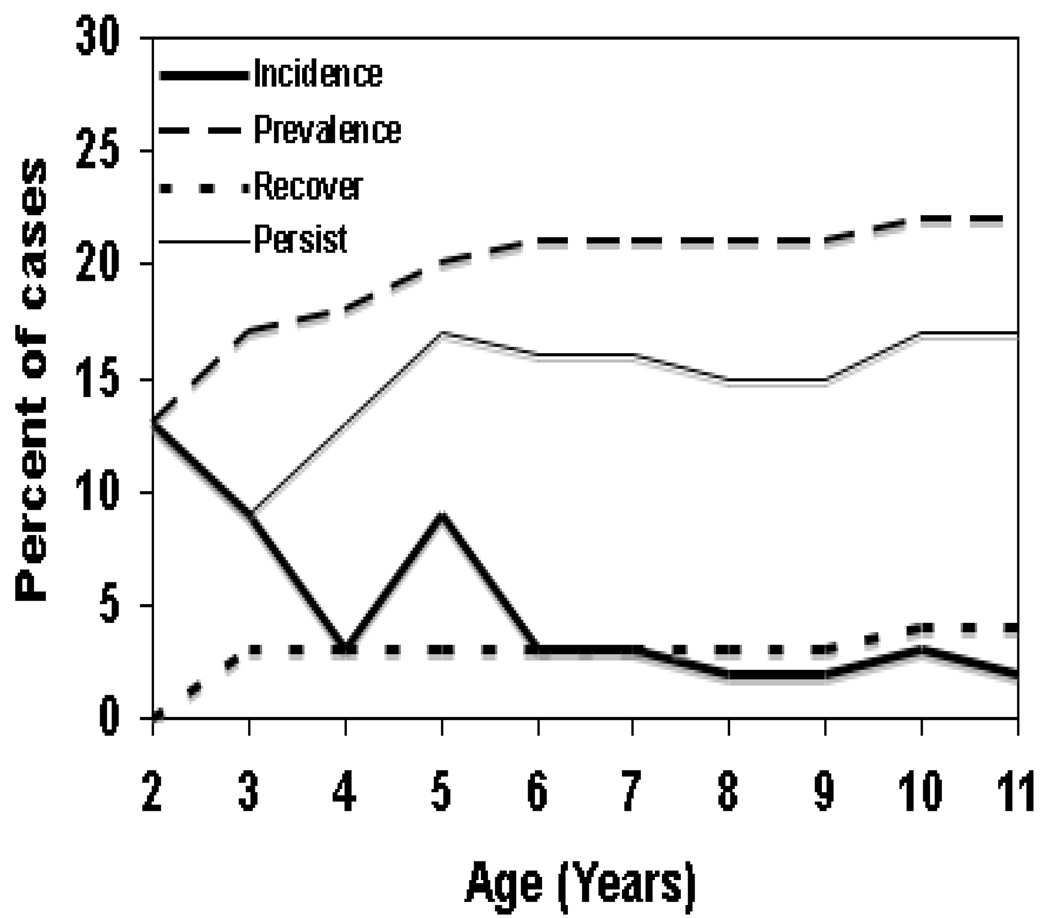

At any given age from 3 to 11 years between 13% and 22% of the children were reported to be picky eaters. Overall, 39% of children were identified as picky eaters at some point during the study. There were no gender differences in the incidence or point prevalence of picky eating hence the combined data are shown by age in Figure 1. As shown the incidence of picky eating declines from 13% to 2% of the sample between 2 and 11 years essentially leveling off at about 3% after 6 years of age. In contrast, point prevalence increases over the same time period. The widening gap between incidence and point prevalence indicates that picky eating tends to persist throughout childhood, hence persistence of picky eating at each age as shown in Figure 1 increasing to age 5 and remaining stable thereafter. However, 58% of picky eaters will recover after 2 years.

Figure 1.

Point prevalence and incidence of picky eating from 3 to 11 years of age expressed as percentages, i.e. rates per 100 children.

Picky eaters comprised 22% (n=26) of the sample at age 11 with 26% (n=16) of the boys and 17% (n=10) of the girls identified as being picky. Parent’s descriptions of these children’s eating behaviors differed significantly from parents of children who did not identify their children as picky eaters (Table 2). Picky eaters were reported to eat a limited variety of foods F(1,115)=104.3 p=.001; required food be prepared in specific ways F(1,115)=27.6 p=.001; were less likely to accept new foods F(1,115)=40.5 p=.001; had strong likes F(1,116)=7.2.3 p=.009; and dislikes of food F(1,116)=27.5 p=.001; and were more likely to have tantrums when parents limited foods F(1,115)=6.7 p=.01. There was a also a gender interaction F(1,115)=4.7 p=.03 for tantrums: boys identified as picky eaters were more likely to exhibit tantrums than both picky girls and non-picky children. There were no differences between the two groups in the distributions of BMI.

Significant differences were also observed across the two groups in the interactions that occurred during feeding (Table 3). Parents who identified their children as picky eaters were more likely to report frequent struggles with their child over food (62%) F(1,116)=38.0, p= .000 than non-picky eaters (12%). The type of food the child preferred rather than the amount was more likely to be the focus of the struggle F(1, 116)=69.4, p=.000. Parents in families with a picky eater were more likely to argue about their child’s eating habits F(1, 116)=8.8, p=.004, than families without a picky eater. Parents of picky eaters were more likely (58%) to prepare a separate meal for their child than parents of non-picky eaters (18%), F(1,116)=18.5, p=.000. Parents of picky eaters were also more likely to comment on their child’s eating habits F(1, 107)=9.9, p=.002 (Table 4) but did not differ between groups in parental pressure to eat or restriction of their child’s eating. Finally, parents of picky boys were more likely to offer a reward to encourage eating (19%) than parents of picky girls (4%) or non-picky eaters (0%) F (1,116)=6.8, p=.01.

Table 4.

Parental restriction and pressure on their child’s eating behavior, parent comments (Child Feeding Questionnaire) and Authoritarian Parenting Style (Parent Authority Questionnaire) mean (SD).

| MALES | FEMALES | TOTAL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Picky n=45 |

Picky n=16 |

Not Picky N=49 |

Picky n=10 |

Not Picky n=94 |

Picky n=26 |

|

| Parental restriction of eating |

3.3(1.2) | 3.4(.9) | 3.3(1.1) | 3.3(1.0) | 3.3(1.1) | 3.4(.9) |

| Parental pressure to eat |

2.7(1.0) | 3.2(1.0) | 2.7(1.0) | 3.0(1.1) | 2.7(1.0) | 3.2(1.0) |

| I usually comment on my child’s eating habits^^ |

1.7(.6) | 2.6(1.0) | 2.0(.8) | 2.4(1.1) | 1.9(.8) | 2.5(1.0) |

| Authoritarian parenting style |

2.6 (.5) | 2.4(.8) | 2.6(.5) | 2.3(.7) | 2.6(.5) | 2.4(.7) |

Pickiness^p<.05 ^ ^p<.01 ^ ^ ^p<.001

Picky eaters of short duration (1 or 2 years) differed from those with a longer duration on several of the child behavior variables listed in Table 2. There was a significant difference in acceptance of new foods with 32% of short duration accepting foods compared with 0% of those with longer duration F(1,45)=10.3, p=.003. Strong likes and dislikes for food also differed. For strong likes (short 64% vs long 100%) F(1,45)=4.8, p=.03 and for strong dislikes (y% 46% vs long 100%) F(1,45)=12.2, p=.001.

Of the parent behaviors listed in Tables 3 and 4 struggles over food differed between the two groups (short 24%, long 62%) F(1,45)=7.7, p=.008 and struggles over particular type of food preferred by the child (short 20% long 62%) F(1,45)=10.0, p=.003. No other variables were significantly different between the groups. Finally, there were no differences on any variables for those with onsets before and after 4-years of age.

4. Discussion

This study assessed the course of picky eating from 2 to 11 years. Previous studies have shown that the prevalence of picky eating was relatively stable during early childhood from 2.5 to 4.5 years (Dubois et al., 2007a) although our findings suggest that prevalence increases during this period. Picky eating showed statistically significant stability when assessed twice over a 10-year span with correlations ranging from 0.12 to 0.63 (Marchi & Cohen, 1990). Moreover a cross-sectional study from Germany of picky eaters later in childhood (8–12 years) exhibited similar characteristics to those described in earlier samples (Jacobi et al., 2008) suggesting that the syndrome is similar from early to late childhood. The present study extends these findings by examining the same cohort of children over a longer time span. The incidence of picky eating was highest in early childhood declining to very low levels by 6 years of age. The percentage of those whose picky eating persisted at each time peaked at age 6 and remained high thereafter suggesting that early onset cases recover more quickly. Over half of all picky eaters recover over a 2-year period irrespective of age of onset. These data suggest that picky eating mainly onsets during early childhood, that the majority of cases are of short duration and may represent various degrees of difficulty in the child fully accepting a wider range of foods. However, a smaller number of picky eaters continue to be a problem for some parents for many years with 47% having a duration longer than 2-years. Picky eaters of longer duration differed from those of short duration in being less likely to accept new foods and showing strong likes and dislikes of food that presumably led to the finding that parents of children with longer duration reported significantly higher rates of struggles over food with their child.

The behaviors comprising picky eating were similar to those of previous studies (Carruth et al., 1998; Dubois et al., 2007a; Jacobi et al., 2008) with children eating a limited variety of foods, often eating only specific foods, and having strong dislikes of certain foods. As noted earlier, rates of picky eating vary considerably between studies. Given the variation in ascertaining picky eating and the varying prevalence across the ages examined in this study, the variation noted across studies is not surprising.

The parental responses to picky eating at 11 years were also similar to those previously reported from the same cohort at 5-years of age (Jacobi et al., 2003) with parents describing frequent struggles with the child over eating, particularly struggles over the type of food, often preparing special meals for the child, and commenting on their child’s eating. However, there were no differences in parental restriction of their child’s eating or in pressure to eat among the parents of picky and non-picky eaters.

The previous findings from the Stanford Feeding Study had shown that picky eaters had a lower sucking frequency in infancy, ate more slowly, and ate fewer calories at 4–5 years of age in a laboratory meal than non-picky eaters. In the present study picky eaters were reported to eat more slowly than non-picky children and to eat less varied foods, but not to eat less than non-picky eaters. This was reflected in the lack of difference in BMI distributions between the two groups. These findings from infancy to late childhood suggest that there may be an inherent tendency for the picky eater to exhibit a less avid eating style. It is likely, at least as determined from animal models (Reed, 2008), that food intake is in part genetically determined possibly explaining the variation in intake observed between picky and non-picky eaters (Dubois et al., 2007a; Jacobi et al., 2003).

Although this study has a number of strengths including frequent assessments between 2 and 11 years on the same cohort of participants and the use of a previously validated measure of picky eating there are some limitations to be considered. First, the sample size is relatively small (N=120). Second, the sample was predominately Caucasian and well educated. Hence the findings may not generalize to other populations. Third, the assessment of picky eating using one question despite initial validation might be improved.

From a clinical viewpoint although picky eating is more likely to develop before age 5, new cases emerge later and there is no difference in child behaviors or parental reactions between cases beginning in early or late childhood. There were, however, differences between those who recovered within 2 years and those with a longer duration of picky eating. The latter children were more likely to have strong likes and dislikes of food and were not likely to accept new foods. Parents of these children were more likely to report struggles with their child over food. Hence, children with these features might merit extra attention from clinicians.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agras WS, Bryson S, Hammer LD, Kraemer HC. Childhood risk factors for thin body preoccupation and social pressure to be thin. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:171–178. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31802bd997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agras WS, Hammer LD, McNicholas F, Kraemer HC. Risk factors for childhood overweight: A prospective study from birth to 9.5 years. Journal of Pediatrics. 2004;145:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, Grimm-Thomas K, Markey CN, Sawyer R, Johnson MB. Confirmatory factor analysis of the child feeding questionnaire: A measure of parental attitudes, beliefs, and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite. 2001;36:201–210. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buri JR. Parental authority questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1989;57:110–119. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruth BR, Skinner J, Houck K, Moran J, Coletta F, Ott D. The phenomenon of “picky eater”: A behavioral marker in eating patterns of toddlers. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 1998;17:180–186. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1998.10718744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruth BR, Ziegler PJ, Gordon A, Barr SI. Prevalence of picky eaters among infants and toddlers and their caregiver’s decsions about offering a new food. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104:S57–S64. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovey TM, Staples PA, Gibson EL, Halfod JCG. Food neophobia and ‘picky/fussy’ eating in children: A review. Appetite. 2008;50:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois L, Farmer A, Girard M, Peterson K, Tatone-Tokuda F. Problem eating behaviors related to social factors and body weight in preschool children: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2007a;4:9. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois L, Farmer AP, Girard M, Peterson K. Preschool children’s eating behaviors are related to dietary adequacy and body weight. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007b;61:846–855. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi C, Agras WS, Bryson S, Hammer LD. Behavioral validation, precursors, and concomitants of picky eating in chldhood. journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:76–84. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200301000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi C, Schmitz G, Agras WS. Is picky eating an eating disorder? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41:626–634. doi: 10.1002/eat.20545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Holm-Denoma JM, Gau JM, Joiner TE, Striegel-Moore RH. Problematic eating and feeding behaviors of 36-month-old children. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;38:208–219. doi: 10.1002/eat.20175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchi M, Cohen P. Early childhood eating behaviors and adolescent eating disorders. journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29:112–117. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199001000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed DR. Animal models of gene-nutrient interactions. Obesity. 2008:S23–S27. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]