Abstract

The eight-point extended Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOSE) is commonly used as the primary outcome measure in traumatic brain injury (TBI) clinical trials. The outcome is conventionally collected through a structured interview with the patient alone or together with a caretaker. Despite the fact that using the structured interview questionnaires helps reach agreement in GOSE assessment between raters, significant variation remains among different raters. We introduce an alternate GOSE rating system as an aid in determining GOSE scores, with the objective of reducing inter-rater variation in the primary outcome assessment in TBI trials. Forty-five trauma centers were randomly assigned to three groups to assess GOSE scores on sample cases, using the alternative GOSE rating system coupled with central quality control (Group 1), the alternative system alone (Group 2), or conventional structured interviews (Group 3). The inter-rater variation between an expert and untrained raters was assessed for each group and reported through raw agreement and with weighted kappa (κ) statistics. Groups 2 and 3 without central review yielded inter-rater agreements of 83% (weighted κ = 0.81; 95% CI 0.69, 0.92) and 83% (weighted κ = 0.76, 95% CI 0.63, 0.89), respectively, in GOS scores. In GOSE, the groups had an agreement of 76% (weighted κ = 0.79; 95% CI 0.69, 0.89), and 63% (weighted κ = 0.70; 95% CI 0.60, 0.81), respectively. The group using the alternative rating system coupled with central monitoring yielded the highest inter-rater agreement among the three groups in rating GOS (97%; weighted κ = 0.95; 95% CI 0.89, 1.00), and GOSE (97%; weighted κ = 0.97; 95% CI 0.91, 1.00). The alternate system is an improved GOSE rating method that reduces inter-rater variations and provides for the first time, source documentation and structured narratives that allow a thorough central review of information. The data suggest that a collective effort can be made to minimize inter-rater variation.

Key words: clinical trial, extended Glasgow Outcome Scale, inter-rater variation, misclassification, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

The eight-point extended Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOSE) was introduced (Jennett et al., 1981) to increase sensitivity of the primary outcome assessment in traumatic brain injury (TBI) trials. However, its assessment appears to be more complex and susceptible to inter-rater variation, as has been suggested by several sets of authors (Brooks et al., 1986; Maas et al., 1983; Marmarou, 2001), compared to the original version, the five-point Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS; Jennett and Bond, 1975).

Conventionally, eight-point GOSE outcome data are collected through a structured interview with the patient, alone or together with a caretaker (Wilson et al., 1998). The structured interview is designed to reduce inter-rater variation through standardizing the questions relative to assessment, and to assist raters in recording the explicit reasons for classification into each GOSE category. Despite the fact that using the structured interview questionnaires helps reach acceptable agreement in GOSE assessment between raters (Pettigrew et al., 1998; Teasdale et al., 1998; Wilson et al., 1998), significant variation remains among different raters. A recent study using the structured interviews indicated an agreement rate as low as 59% (weighted kappa [κ] = 0.72; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.62, 0.75) for GOSE assessment by untrained investigators (Wilson et al., 2007).

Inter-rater variation in primary outcome rating is a serious concern that may have contributed to the lack of positive results in some TBI trials (Maas et al., 1999; Marmarou, 2001; Narayan et al., 2002). A study by Choi and colleagues (Choi et al., 2002) indicated that the effect of misclassification on GOS may not only decrease the desired power of a trial, but also the size of true benefit. Thus observer variation or outcome misclassification may obscure therapeutic effects by introducing errors into the true study efficacy. We (Lu et al., 2008) recently reported that a 20% random misclassification on a dichotomous GOS outcome could reduce the treatment effect from the expected 10% to 6.8%, while maintaining the statistical power as a fixed factor.

The consistency and reliability of the outcome assessment could be influenced by many factors. Thus a collective effort by all possible means should be made to ensure the quality of the assessment. Here we introduce an alternate GOSE rating system as an aid in determining GOSE scores with the objective of reducing inter-rater variation in the primary outcome assessment in TBI trials.

The method used in this study is based on the concept that the GOSE is an extension of the GOS and as such, effort is focused on obtaining a reliable GOS score, and then limiting the questions asked in order to obtain a reliable GOSE score. More importantly, the method requires the investigator to record pre- and post-injury narratives to establish firm baselines, and source documentation that provides quality assurance through central monitoring to determine a reliable outcome and reduce clerical errors.

Methods

Study participation centers and design

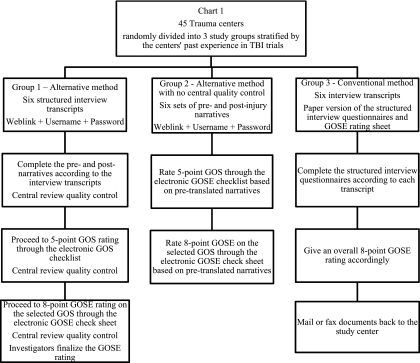

Forty-five trauma centers in the United States were invited to participate in this study. These centers are members of the active American Brain Injury Consortium (ABIC) currently selected to participate in a Phase III TBI trial. The selection was based on the centers' past experience in TBI trials, the existing data regarding the annual volume of TBI patient enrollments, and the level of correspondence with ABIC. The selected centers were randomly divided into three study groups of equal size as balanced by the center's past experiences in TBI trials. These three groups were assigned to use different methods to assess patient 6-month GOSE outcome as described in Figure 1.

FIG. 1.

Forty-five trauma centers were randomly divided into three study groups balanced by each center's past experience in TBI trials. Group 1 used the alternative GOS/GOSE rating system coupled with central quality control, in which the raters were required to complete six sets of pre- and post-injury narratives according to six sample transcripts prior to outcome assessment. Group 2 used the alternative system with no central quality control, in which the raters used six sets of pre-specified narratives to rate the outcome. These narratives contained information, strictly transferred from the original interview transcripts by an expert, which allowed the validation of GOS/GOSE assessment without errors introduced by incorrect narratives. Group 3 used conventional structured interviews in which the raters were required to fill out the structured GOSE interview questionnaires based on the same six transcripts, and to provide an overall GOSE rating of the case (GOS, Glasgow Outcome Scale; GOSE, extended Glasgow Outcome Scale; TBI, traumatic brain injury).

Group 1 used the alternative GOS/GOSE rating system coupled with central quality control, in which the raters were required to complete six sets of pre- and post-injury narratives according to six sample transcripts prior to the outcome assessment. Group 2 used the alternative system with no central quality control, in which the raters used six sets of pre-specified narratives to rate the outcome. These narratives contained information, strictly transferred from the original interview transcripts by an expert, which allowed the validation of GOS/GOSE assessment without errors introduced by incorrect narratives. Group 3 used conventional structured interviews in which the raters were required to fill out the structured GOSE interview questionnaires based on the same six transcripts, and to provide an overall GOSE score for the case. For each study group, the raters were given brief written instructions as to how to use the alternative system or conventional method to complete the outcome assessment. No additional training was given to the investigators. For study Group 1, the raters were informed that a central reviewer would monitor the rating process.

The alternative method was a web-based GOSE rating system, which required recording the structured pre- and post-injury narratives initially to establish firm baselines and source documentation. Based on the narratives, the system first captured the score on the five-point GOS according to six structured yes/no questionnaires. After the GOS category was defined, the system presented the raters with the criteria (Table 1) for the upper or lower strata of a particular GOS category in order to arrive at the GOSE. As such, only the questions relevant to the patient's GOS category were presented. For example, if the GOS was rated as moderate disability, the electronic system would route the rater to a screen where only questions regarding the upper and lower strata of moderate disability were presented. (A set of the pre- and post-injury narratives and GOS and GOSE checklists is available as an online only supplement at www.liebertonline.com.)

Table 1.

Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) and Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOSE)

|

Five-point GOS |

Eight-point GOSE |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Key definitiona | Key criteriab | Category | Key criteriab |

| Good recovery (GR) | A patient is capable of resuming normal occupational and social activities with or without minor physical or mental deficits | 1. Returns to work at the same level of performance as pre-injury and 2. Resumes at least more than half of the pre-injury level of social and leisure activities |

Upper (GR+) Lower (GR−) |

Returns to normal life with no current problems related to the head injury that affect daily life 1. Returns to pre-injury normal life, but has minor problems that affect daily life and/or 2. Resumes more than half the pre-injury level of social and leisure activities and/or 3. Disruption is infrequent (less than weekly) |

| Moderate disability (MD) | A patient is fully independent but disabled | 1. Work capacity is reduced or unable to work and/or 2. Resumes less than half the pre-injury level of social and leisure activities |

Upper (MD+) | 1. Work capacity is reduced and/or 2. Resumes less than half the pre-injury level of social and leisure activities and/or 3. Disruption is frequent (once a week or more) but tolerable |

| Lower (MD−) | 1. Only able to work in sheltered workshop or unable to work and/or 2. Rarely or unable to participate in social/and leisure activities and/or 3. Disruption is constant (daily) and intolerable |

|||

| Severe disability (SD) | A patient is conscious but needs the assistance of another person for some activities of daily living every day | 1. Requires the help of someone to be around at home with activities of daily living and/or 2. Unable to travel or go shopping without assistance |

Upper (SD+) Lower (SD−) |

Can be left alone at least 8 h during the day, but unable to travel and/or go shopping without assistance Requires frequent help of someone to be around at home most of the time every day |

| Vegetative status (VS) | Patient shows no evidence of meaningful responsiveness | Vegetative status (VS) | ||

| Death (D) | Death (D) | |||

Moreover, a quality control system was built into the rating process that provided quality assurance through the use of a central reviewer. For instance, after the raters in Group 1 completed the pre- and post-injury narratives for each patient case, using information from the sample transcripts, a central reviewer would check whether the transferred narratives reflected accurate and sufficient information for assessing the outcome, compared with the original transcripts. The focus of the central review was to determine if there was sufficient information in all categories of the GOS/GOSE to arrive at an accurate assessment. Feedback from the central reviewer allowed the raters to re-check the narrative information if it was incomplete, or to proceed to the next step. The same quality control was performed after the raters completed each assessment of the five-point GOS and the eight-point GOSE, according to the raters' narratives. The investigators made the final decision based on the overall rating and the comments from the central review. Care was taken not to lead the investigators to a specific rating, but only to ensure that the information in the narrative was sufficient based on classic guidelines for GOS/GOSE assessment. In this way, the narratives served as a verifiable source document for the GOS and GOSE assessments.

Study material and outcome

Six transcripts of structured outcome interviews with patients with head injury or their relatives were used in order to assess the GOSE outcome. These transcripts contained real patient data originating from previous studies, and were also used in the dexanabinol study (Wilson et al., 2007) to assess baseline agreement between raters. The cases selected were not intended to be specifically representative of “easy” or “difficult” cases, but they covered the range of GOSE outcomes, from lower severe disability to lower good recovery, as assigned by an expert according to the criteria for the GOSE categories. The transcripts were distributed electronically to the study participating centers in two formats. For study Groups 1 and 3, the centers received the original interview transcripts; for Group 2, the centers received six sets of pre-specified pre- and post-injury narratives that were transferred from the transcripts as described previously. No additional information regarding the outcome and the severity of injury were provided for these cases.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed the quality and inter-rater variation in GOS/GOSE assessment by the alternative GOSE data collection system (Groups 1 and 2). The results for outcome assessment were then compared against the results obtained using the conventional structured GOSE interviews (Group 3).

To identify whether central quality control played an important role in reducing inter-rater variation in the assessment of GOSE for the alternative method, we first applied the descriptive analyses and listed the discrepancies found in each step of the central quality check-ups for Group 1, including the steps of transferring patient responses from the original transcripts to pre-injury and post-injury narratives, and the assessments of the five-point GOS and the eight-point GOSE. We then compared the agreement rate in outcome ratings between the expert and the raters among all study groups.

Further, to examine whether the two-stage GOSE assessment (i.e., assessing the five-point GOS first, then the eight-point GOSE) by the alternative system was more effective in reducing inter-rater variation, we compared the ratings for both five-point GOS and eight-point GOSE for all three groups through cross-tabulations.

The inter-rater agreement was assessed using weighted kappa (κ) statistics (Cohen, 1968). The weighted κ was developed to give more emphasis to the degree of disagreement. The conventional “weight” used for assessing disagreement in ordered categorical data was a quadratic weight. In general, the strength of agreement could be described by κ statistics as poor (<0.2), fair (>2 to ≤0.4), moderate (>0.4 to ≤0.6), good (>0.6 to ≥0.8), and very good (>0.8 to ≤1; Landis and Koch, 1977). The weighted κ and its 95% confidence interval (CI), as well as the raw agreement rate were reported.

Results

Characteristics of the study centers

A total of 45 trauma centers were invited to participate and 32 centers volunteered to complete the study. The overall participation rate was 71%, and the participation rates for Groups 1, 2, and 3 were 67%, 73%, and 73%, respectively. The characteristics of the study participating centers and the raters' past experience in TBI trials and their current occupation status are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

The Characteristics of the Study Centers by Group

| Characteristic | Alternative system | Alternative system without central monitoring | Conventional structured interview |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participation rate | 67% (10/15) | 73% (11/15) | 73% (11/15) |

| Rater's past experience in TBI trials (n) | 7 (7/10) | 6 (6/11) | 6 (6/11) |

| Rater's occupation status (n) | |||

| Physician | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Neuropsychologist | 2 | ||

| Nurse | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Other | 1 | 1 | 1 |

The alternative GOSE rating system: Observation from central review

The analysis regarding the rule of central quality control for the alternative GOSE rating system was conducted for study Group 1. The raters completed three processes sequentially through the electronic rating system: pre/post narratives, GOS rating, and GOSE rating. Ten raters each completed the three processes, including the transfer of information to the narratives, and rating of GOS followed by rating of GOSE for six cases. Out of 60 sample cases and 180 rating processes, the central reviewer identified 28 (28 out of 180) discrepancies, including 13 (13 out of 60) discrepancies in the process of writing the post narratives, six (6 out of 60) in the five-point GOS assessment, and nine (9 out of 60) in the eight-point GOSE assessment. The investigators made the final decision on the overall rating, and the comments from central review resulted in rectifying 26 of the 28 discrepancies.

Major reasons for the discrepancies identified by the central reviewer for Group 1 are summarized in Table 3. Out of 13 discrepancies that occurred in the process of writing the post narratives, nine of those were because the raters did not respond to the specific questions that were required by the post narratives, while four cases were attributable to the raters' misinterpretation of the original information from the transcripts. For the six and nine discrepancies that were identified for the GOS and GOSE ratings, respectively, almost all discrepancies occurred because of incorrect outcome ratings based on the narratives. Namely, the narratives were correct, but the outcome rating was not in agreement with the narratives.

Table 3.

Discrepancies Identified by the Central Reviewer during the Outcome Rating Process for Group 1

| Overall discrepancies n = 180 | Pre/post narrative set n = 60 | Five-point GOS n = 60 | Eight-point GOSE n = 60 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) of discrepancies | 28 (16) | 13 (22) | 6 (10) | 9 (15) |

| Reasons for discrepancies | ||||

| Incorrect transfer of information from the transcripts (e.g., patient able to work, narrative says no) | 4 cases | |||

| The key criteria for GOSE assessment was missing in the narratives (e.g., more/less than half social activity) | 9 cases | |||

| Incorrect GOS/GOSE ratings based on the Narrative information | 5 cases | 9 cases | ||

| Other | 1 case | |||

| Number (%) of discrepancies corrected | 26 (26/28) | 12 (12/13) | 6 (5/6) | 9 (9/9) |

GOS, Glasgow Outcome Scale; GOSE, extended Glasgow Outcome Scale.

Observer variation in assessment of the eight-point GOSE

The evaluation of consistency in eight-point GOSE assessment was conducted for all study groups as shown in Table 4a. For study Group 1, which was assigned to use the alternative GOSE rating system, the overall agreement in GOSE assessment between a central reviewer and the raters was 97% (weighted κ = 0.97; 95% CI 0.91, 1.00). This agreement rate was based on both investigators' overall rating and the central reviewer's comments. On two occasions the investigator disagreed with the comments from the central reviewer.

Table 4a.

Comparison between the Alternative Eight-point GOSE Data Collection Method and the Conventional Structured Interviews: Agreement between a Central Reviewer and the Investigators on Rating Six Sample Case Transcripts

| |

|

|

Investigator rating |

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOSE collection method | Transcript | Expert | VS | SD− | SD+ | MD− | MD+ | GR− | GR+ | Agreement |

| Alternative system (n = 60) | A | SD− | 10 | 100% | ||||||

| B | SD+ | 10 | 100% | |||||||

| C | MD− | 10 | 100% | |||||||

| D | MD+ | 10 | 100% | |||||||

| E | MD+ | 1 | 9 | 90% | ||||||

| F | GR− | 1 | 9 | 90% | ||||||

| Overall agreement 97% (weighted κ = 0.97 and 95% confidence interval 0.91, 1.00) | ||||||||||

| Alternative system without central monitoring (n = 66) | A | SD− | 10 | 1 | 92% | |||||

| B | SD+ | 11 | 100% | |||||||

| C | MD− | 1 | 5 | 5 | 45% | |||||

| D | MD+ | 2 | 9 | 82% | ||||||

| E | MD+ | 2 | 9 | 82% | ||||||

| F | GR− | 4 | 6 | 1 | 55% | |||||

| Overall agreement 76% (weighted κ = 0.79 and 95% confidence interval 0.69, 0.89) | ||||||||||

| Conventional structured interview (n = 66) | A | SD− | 6 | 5 | 55% | |||||

| B | SD+ | 9 | 2 | 82% | ||||||

| C | MD− | 1 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 55% | ||||

| D | MD+ | 1 | 7 | 3 | 64% | |||||

| E | MD+ | 1 | 4 | 6 | 55% | |||||

| F | GR− | 2 | 7 | 2 | 64% | |||||

Overall agreement 63% (weighted κ = 0.70 and 95% confidence interval 0.60, 0.81).

GR, good recovery; MD, moderate disability; SD, severe disability; VS, vegetative status; GOSE, extended Glasgow Outcome Scale.

Group 2 utilized the alternative rating system as well, but with no central quality control. The overall agreement rate in GOSE assessments between an expert and untrained raters was 76% (weighted κ = 0.79; 95% CI 0.69, 0.89). In general, the raters did well in assessing the categories of lower and upper severe disabilities, for which the agreement rate between the central reviewer and raters reached 92% and 100%, respectively. However, the raters seemed to have more problems when assessing the sample cases of moderate disability and good recovery. The agreement rates in assessing the lower moderate GOSE equaled 45%, upper moderate GOSE 82%, and lower good GOSE 55%.

For the six lower moderate disability cases that an expert and the raters disagreed upon, five were due to the judgment of the patient's current occupational status and/or the degree of the social and leisure activities resumed. In four disputed upper moderate disability cases, three were related to the inquiry as to whether the patients' current ability to drive or use public transportation was due to head injury or for some other reason. Finally, for five lower good recovery cases, four were not agreed upon as to whether the patient was able to return to their prior injury social and leisure activities by at least 50%.

Compared with the groups using the alternative rating system, the overall agreement between an expert and raters in Group 3 was lower. The overall agreement for Group 3 only reached 63% (weighted κ = 0.70; 95% CI 0.60, 0.81). The agreement rates between an expert and the raters in assessing the categories were as follows: lower and upper severe disabilities (55% and 82%), lower and upper moderate disabilities (55% and 60%), and lower good recovery (64%). Moreover, the observed assessment disparity among the outcome categories was wider, especially in the assessment of moderate disabilities.

For the severe disability cases, except for one case of misunderstanding, six mistakes were due to algorithm issues. For the moderate disability categories, the majority of errors were in the area of social and leisure activities and/or current occupational status, for which the raters were required to exercise their own judgment in assessing if the social and leisure activities were more or less than 50%. Finally, the errors in rating the good recovery category were also seen mostly in the area of social and leisure activities.

Observer variation in assessment of the five-point GOS

The observer variation in the assessment of the five-point GOS is summarized in Table 4b. The performance on the five-point GOS rating scale was generally better among all study groups compared to the eight-point GOSE assessment. For Groups 1 and 2, that used the alternative approach to rate the outcome, the overall agreement between an expert and the raters were 97% (weighted κ = 0.95; 95% CI 0.89, 1.00), and 83% (weighted κ = 0.81; 95% CI 0.69, 0.92), respectively. For Group 3, that used the conventional method, the overall agreement reached 83% (weighted κ = 0.76; 95% CI 0.63, 0.89).

Table 4b.

Comparison between the Alternative Five-Point GOS Data Collection Method and the Conventional Structured Interviews: Agreement between a Central Reviewer and Investigators on Rating of Six Sample Case Transcripts

| |

|

Investigator rating |

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert | VS | SD | MD | GR | Agreement | |

| Alternative method (n = 60) | SD | 20 | 100% | |||

| MD | 1 | 29 | 97% | |||

| GR | 1 | 9 | 90% | |||

| Overall agreement 97% (weighted κ = 0.95 and 95% confidence interval 0.89, 1.00) | ||||||

| Alternative method without central monitoring (n = 66) | SD | 22 | 100% | |||

| MD | 5 | 28 | 85% | |||

| GR | 4 | 7 | 64% | |||

| Overall agreement 83% (weighted κ = 0.81 and 95% confidence interval 0.69, 0.92) | ||||||

| Conventional structured interview (n = 66) | SD | 20 | 2 | 91% | ||

| MD | 3 | 25 | 5 | 76% | ||

| GR | 2 | 9 | 82% | |||

Overall agreement 83% (weighted κ = 0.76 and 95% confidence interval 0.63, 0.89).

GR, good recovery; MD, moderate disability; SD, severe disability; VS, vegetative status; GOS, Glasgow Outcome Scale.

In accordance with the assessment of the eight-point GOSE, the raters did well on rating severe disability. The agreement rate between an expert and the raters for Groups 1 and 2 reached 100% and 100%, respectively, and the rate for Group 3 was 91%. However, the raters were less in agreement with the expert in the assessment of better GOS outcome categories. For Groups 1, 2, and 3, the agreement rates were 97%, 85%, and 76%, in the assessment of moderate disabilities, and 90%, 64%, and 82% in the assessment of good recovery, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we used an alternative GOSE rating system to aid the assignment of outcome scores with the objective of reducing the inter-rater variation in the primary outcome assessment in TBI trials. The proposed system is an extension of the existing ABIC five-point GOS checklist, which was developed for the purpose of reducing inter-rater variation in GOS assessment in TBI trials (Wilson et al., 1998). The GOS checklist has been shown to decrease interobserver variability in a pilot trial (Marmarou, 2001), and was used in two TBI clinical trials (Marmarou et al., 1999, 2005). The current system adds additional criteria, while maintaining the five-point GOS rating criteria, to assess the use of the eight-point GOSE system, as directed by the guidelines (Wilson et al., 1998). In addition, the alternative system takes advantage of electronic data capture to (1) integrate a quality-control system into the rating process, which provides improved quality assurance through use of a central reviewer, (2) utilize an algorithm to arrive at the GOS score, and (3) to only present the questions separating the upper and lower categories of a specific GOS rating to arrive at the GOSE score.

The results of this study indicate that inter-rater variations in the outcome assessment can be reduced through the improved outcome data collection system. For study Group 1, which utilized the complete alternative system in which a central quality-control system was built into the rating process, the overall agreement rate between an expert and the raters in the assessment of the five-point GOS (weighted κ = 0.95; 95% CI 0.89, 1.00), and the eight-point GOSE (weighted κ = 0.97; 95% CI 0.91, 1.00), reached 97%. These results are superior to those of previous studies (Brooks et al., 1986; Maas et al., 1983; Marmarou, 2001; Wilson et al., 1998, 2007), as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Agreement and Kappa in Previously Reported GOS/GOSE Assessments

| |

|

Overall agreement rate |

Weighted kappa statistics (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Methods | GOS | GOSE | GOS | GOSE | |

| Maas et al.,1983 | 1. Patient interview and sample cases 2. Agreement between physicians |

Structured questionnaires Patient interview: Sample cases: |

86% 81% |

60% 62% |

0.77 (0.55, 0.99)a 0.71 (0.54, 0.88)a |

0.48 (0.28, 0.68)a 0.52 (0.34, 0.70)a |

| Brooks et al.,1986 | 1. Patient cases 2. Agreement between two experienced raters |

70% | 46% | – | – | |

| Wilson et al., 1998 | 1. Patient interview 2. Agreement between investigators |

Structured interview: | 92% | 78% | 0.89 (−) | 0.85 (−) |

| Marmarou, 2001 | 1. Sample cases 2. Agreement between experts and investigators |

GOS checklist | 82% | – | ||

| Wilson et al., 2007 | 1. Sample cases 2. Agreement between experts and untrained investigators |

Structured interviews: | 59% | – | 0.72 (0.68, 0.75) | |

| Lu et al., 2008 | 1. Sample cases 2. Agreement between experts and untrained investigators |

Alternative system with central review: Structured interview: |

97% 83% |

97% 63% |

0.95 (0.89, 1.00) 0.76 (0.63, 0.89) |

0.97 (0.91, 1.00) 0.70 (0.60, 0.81) |

Unweighted kappa statistics.

GOS, Glasgow Outcome Scale; GOSE, extended Glasgow Outcome Scale; CI, confidence interval.

Furthermore, the use of the alternative system alone (Group 2), without central monitoring, also demonstrated strength in lessening the variation in the eight-point GOSE assessment among untrained raters, especially in the assessment of lower and upper severe disability categories (Table 4a). The overall agreement, weighted κ, and CI [GOS 83%, 0.81, and (0.69, 0.92), GOSE 76%, 0.79, and (0.69, 0.89)] in the outcome assessment were better than the results reported earlier, and consistent with more recent results (Marmarou, 2001; Wilson et al., 1998, 2007). The results from Group 3, that used the conventional structured interviews, are in close agreement with the baseline variability found in the dexanabinol trial. (Wilson et al., 2007).

Moreover, this study provided valuable insights into (1) potential causes of inter-rater variations during the outcome assessment process, and (2) the impact of an improved outcome rating system on constraining such variations in the course of assessment. The proposed system may help reduce the variation in the assessment of the eight-point GOSE through the following approaches.

Pre-injury narratives

The first step in this alterative system was to collect a pre-injury narrative within 2 weeks post-injury. This helped in determining the true impact of head injury on an individual's daily functioning, by taking into consideration the pre-injury status for each of the areas included in the GOS and GOSE assessment scales. Given the performance of Group 1 raters, the description and format of the pre-injury narrative appeared to be sufficient to serve as an important baseline reference. In comparison with sample cases, no disagreement with the narratives was shown between the central reviewer and raters. Thus it appears that these narratives in the module are user-friendly and self-exploratory for future use in TBI trials.

Three- and 6-month post-injury narratives

Since this alternative system requires an investigator responsible for the outcome assessment to collect the data for the 3- and 6-month post-injury narratives after documenting patient function as described above for the pre-injury narratives, this indicates that each patient serves as their own control. As such, a reduction in GOS score will more clearly reflect the result of the patient's head injury. These narratives provide not only the necessary information for the outcome rating, but also critical source documentation for the purpose of quality control.

In this study, we found that most raters were able to properly record the post-injury information according to the descriptions of the post-injury narratives. Out of 13 post-injury narratives that the central reviewer had to query, nine cases were due to the raters' failure to respond to the questions required, and four were caused by the raters' misinterpretation of sample cases. At least two main reasons may explain these errors. For instance, the raters' prior knowledge and experience in utilizing a rating instrument may be an important factor. In the absence of knowledge of the basic concepts and understanding of the outcome and rating process, a rater does not possess the information necessary to assess the outcome, even when the information is available, as suggested by the results of several previous studies. In this regard, Clifton and colleagues (2001) demonstrated that higher-enrollment centers were superior in data completion, outcome assessment, and overall patient management, compared to lower-enrollment centers. Wilson and associates (2007) also showed that the central review identified a relatively large number of discrepancies (29–37%) during the early stages of a trial, but the number declined as the trial progressed, which coincided with more extensive investigator training and feedback from the central review.

Moreover, a loosely-structured question format leads to an open-ended answer and flexibility for the raters to provide their answers. As such, using a mixture of open-ended and pre-categorized answers would be expected to improve data collection. For example, loosely-structured more open-ended answers allows raters to better document an individual's post-injury condition, while the fixed pre-categorized answers facilitates a standardized outcome rating among the patient population. This may be particularly meaningful with regard to the key concepts that differentiate the GOS and GOSE categories, as shown in Table 1.

It should be pointed out that in this study, the raters were able to obtain feedback from a central reviewer and had the opportunity to correct an error in narrative writing before the rating process. Thus, we recommend (1) acquiring the necessary knowledge about the outcome and its assessment instrument prior to a trial, (2) practicing on sample cases before the actual assessment is carried out, (3) collecting complete information in accordance with the requirements outlined in the narratives, and (4) checking the consistency of their own narratives.

A two-stage GOS and GOSE rating system

The alternative GOSE rating system requires the investigators to rate the less complicated five-point GOS first, followed by rating the eight-point GOSE category, by subdividing the selected GOS category into a “lower” or “upper” category. The rating on the five-point GOS is based on a checklist that contains the same category and layout of the source documentation (i.e., the pre- and post-injury narratives). But the eight-point GOSE rating is based on a compilation sheet in which the information is extracted from the pre-categorized answers of the post-injury narrative sheet. Thus, this system provides a two-stage rating process, thereby minimizing potential observer variations across the five-point GOS outcome categories, and simplifies the assessment of the eight-point GOSE.

To date, this system has been used to collect 6-month GOSE data for an observational study, including both U.S and European centers. In this validation study, we found that a two-stage outcome rating system was, in general, an improvement over the conventional approach in the eight-point GOSE assessment. The improvement was particularly noticeable in the assessment of severe disability. For instance, of 22 lower and upper severe disability sample cases, the expert had only one disagreement with the ratings obtained from Group 2, in which the two-stage system was used, whereas the expert had seven disagreements (7/22) from Group 3, in which the conventional method was applied. It seems that the more reliable rating outcome for Group 2 was directly related to the use of the two-stage system, which simplified the rating process and automated the rating algorithms. This is especially evident in light of the fact that neither group received feedback from the central quality control, and both used the same sample cases.

Study limitations

Although studies of inter-rater variations using central reviews or ratings from sample cases can reveal inconsistencies in outcome assessment, they are unlikely to capture every potential type of variation. In practice, the outcome assessment may be more complex, and the results may be further influenced by how the questions are asked and responses are solicited. Thus, the inter-observer agreements obtained in this study, based on sample transcripts, cannot be directly extrapolated to the clinical situation when assessing actual patients. Also, the results of this study were obtained from a relatively small group of investigators. Further study with larger groups of investigators in actual interview situations are needed to further confirm the results of this study. Moreover, the method of using case histories does not allow further information to be gathered over what has already been collected in the sample cases.

Nevertheless, since the sample cases used in this study were originally obtained through the structured interviews, and used in a large Phase III head injury trial GOSE inter-observer variation study (Wilson et al., 2007), it was reasonable to believe that the information obtained from these cases included sufficient information to assess patient outcome. Therefore, we believe that these sample cases are useful to validate whether (1) the criteria described in the narratives provide sufficient information for outcome assessment, and (2) the alternative GOSE rating system itself is better at reducing variations in GOSE assessment than conventional structured interviews.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that the alternative method for GOSE assessment has several advantages over current techniques. First, a narrative provides source documentation about the pre-injury status, and the status at 3 and 6 months post-injury, thus allowing for a more thorough central review. Second, a GOS-structured checklist provides an easy and practical method for GOS assessment. Third, an electronic system that directs the investigator to focus on an upper or lower classification of the GOSE criteria provides an easy and practical method for GOSE assessment. Taken together these elements, coupled with the central review, allow a more reliable GOSE rating system, thus reducing inter-rater variation and misclassification. The results of this study emphasize the importance of combining all efforts to reduce outcome misclassification, including the use of a reliable outcome rating system, collection of sufficient standardized information, proper rater training, and central quality control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Support for this work was provided by National Institutes of Health grant NS 42691.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Participating Study Centers

Allegheny General Hospital, Christiana Care Health Services, Froedtert Memorial Lutheran Hospital/MCW, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Hennepin County Medical Center, John Peter Smith Hospital, Legacy Health System, Loyola University Medical Center, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-Shreveport, Maricopa Integrated Health System, Miami Valley Hospital, Mount Sinai Hospital Medical Center-Chicago, St. Louis University Hospital, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Springfield Neurological and Spine Institute, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey University Hospital, University of California-Davis Medical Center, University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics, University of Cincinnati Medical Center, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, University of Miami, University of Mississippi Medical Center, University of New Mexico, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center at Memphis, University of Utah Health Sciences Center, University of Virginia Health System, Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, West Virginia University Hospitals, Wishard Memorial Hospital.

References

- Brooks D.N. Hosie J. Bond M.R. Jennett B. Aughton M. Cognitive sequelae of severe head injury in relation to the Glasgow Outcome Scale. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1986;49:549–553. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.49.5.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.C. Clifton G.L. Marmarou A. Miller E.R. Misclassification and treatment effect on primary outcome measures in clinical trials of severe neurotrauma. J. Neurotrauma. 2002;19:17–22. doi: 10.1089/089771502753460204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton G.L. Choi S.C. Miller E.R. Levin H.S. Smith K.R., Jr. Muizelaar J.P. Wagner F.C., Jr. Marion D.W. Luerssen T.G. Intercenter variance in clinical trials of head trauma—experience of the National Acute Brain Injury Study: Hypothermia. J. Neurosurg. 2001;95:751–755. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.95.5.0751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol. Bull. 1968;70:213–220. doi: 10.1037/h0026256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennett B. Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet. 1975;1:480–484. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92830-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennett B. Snoek J. Bond M.R. Brooks N. Disability after severe head injury: observations on the use of the Glasgow Outcome Scale. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1981;44:285–293. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.44.4.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis J.R. Koch G.G. An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics. 1977;33:363–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J. Murray G.D. Steyerberg E.W. Butcher I. McHugh G.S. Lingsma H. Mushkudiani N. Choi S. Maas A.I. Marmarou A. Effects of Glasgow Outcome Scale misclassification on traumatic brain injury clinical trials. J. Neurotrauma. 2008;25:641–651. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas A.I. Braakman R. Schouten H.J. Minderhoud J.M. van Zomeren A.H. Agreement between physicians on assessment of outcome following severe head injury. J. Neurosurg. 1983;58:321–325. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.58.3.0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas A.I. Murray G. Henney H., 3rd Kassem N. Legrand V. Mangelus M. Muizelaar J.P. Stocchetti N. Knoller N. Pharmos TBI investigators. Efficacy and safety of dexanabinol in severe traumatic brain injury: results of a phase III randomised, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:38–45. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas A.I. Steyerberg E.W. Murray G.D. Bullock R. Baethmann A. Marshall L.F. Teasdale G.M. Why have recent trials of neuroprotective agents in head injury failed to show convincing efficacy? A pragmatic analysis and theoretical considerations. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:1286–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmarou A. Guy M. Murphey L. Roy F. Layani L. Combal J.P. Marquer C. American Brain Injury Consortium. A single dose, three-arm, placebo-controlled, phase I study of the bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist Anatibant (LF16-0687Ms) in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2005;22:1444–1455. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmarou A. Head Trauma: Basic, Preclinical, Clinical Direction. 1st. Wiley; New York: 2001. p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Marmarou A. Nichols J. Burgess J. Newell D. Troha J. Burnham D. Pitts L. Effects of the bradykinin antagonist Bradycor (deltibant, CP-1027) in severe traumatic brain injury: results of a multi-center, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. American Brain Injury Consortium Study Group. J. Neurotrauma. 1999;16:431–444. doi: 10.1089/neu.1999.16.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan R.K. Michel M.E. Ansell B. Baethmann A. Biegon A. Bracken M.B. Bullock M.R. Choi S.C. Clifton G.L. Contant C.F. Coplin W.M. Dietrich W.D. Ghajar J. Grady S.M. Grossman R.G. Hall E.D. Heetderks W. Hovda D.A. Jallo J. Katz R.L. Knoller N. Kochanek P.M. Maas A.I. Majde J. Marion D.W. Marmarou A. Marshall L.F. McIntosh T.K. Miller E. Mohberg N. Muizelaar J.P. Pitts L.H. Quinn P. Riesenfeld G. Robertson C.S. Strauss K.I. Teasdale G. Temkin N. Tuma R. Wade C. Walker M.D. Weinrich M. Whyte J. Wilberger J. Young A.B. Yurkewicz L. Clinical trials in head injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2002;19:503–557. doi: 10.1089/089771502753754037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew L.E. Wilson J.T. Teasdale G.M. Assessing disability after head injury: improved use of the Glasgow Outcome Scale. J. Neurosurg. 1998;89:939–943. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.6.0939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale G.M. Pettigrew L.E. Wilson J.T. Murray G. Jennett B. Analyzing outcome of treatment of severe head injury: a review and update on advancing the use of the Glasgow Outcome Scale. J. Neurotrauma. 1998;15:587–597. doi: 10.1089/neu.1998.15.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J.T. Pettigrew L.E. Teasdale G.M. Structured interviews for the Glasgow Outcome Scale and the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale: guidelines for their use. J. Neurotrauma. 1998;15:573–585. doi: 10.1089/neu.1998.15.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J.T. Slieker F.J. Legrand V. Murray G. Stocchetti N. Maas A.I. Observer variation in the assessment of outcome in traumatic brain injury: experience from a multicenter, international randomized clinical trial. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:123–128. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000279732.21145.9e. discussion 128–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.