Abstract

We reported that adenosine A1 receptor (A1AR) knockout (KO) mice develop lethal status epilepticus after experimental traumatic brain injury (TBI), which is not seen in wild-type (WT) mice. Studies in epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and neuro-oncology suggest enhanced neuro-inflammation and/or neuronal death in A1AR KO. We hypothesized that A1AR deficiency exacerbates the microglial response and neuronal damage after TBI. A1AR KO and WT littermates were subjected to mild controlled cortical impact (3 m/sec; 0.5 mm depth) to left parietal cortex, an injury level below the acute seizure threshold in the KO. At 24 h or 7 days, mice were sacrificed and serial sections prepared. Iba-1 immunostaining was used to quantify microglia at 7 days. To assess neuronal injury, sections were stained with Fluoro-Jade C (FJC) at 24 h to evaluate neuronal death in the hippocampus and cresyl violet staining at 7 days to analyze cortical lesion volumes. We also studied the effects of adenosine receptor agonists and antagonists on 3H-thymidine uptake (proliferation index) by BV-2 cells (immortalized mouse microglial). There was no neuronal death in CA1 or CA3 quantified by FJC. A1AR KO mice exhibited enhanced microglial response; specifically, Iba-1 + microglia were increased 20–50% more in A1AR KO versus WT in ipsilateral cortex, CA3, and thalamus, and contralateral cortex, CA1, and thalamus (p < 0.05). However, contusion and cortical volumes did not differ between KO and WT. Pharmacological studies in cultured BV-2 cells indicated that A1AR activation inhibits microglial proliferation. A1AR activation is an endogenous inhibitor of the microglial response to TBI, likely via inhibition of proliferation, and this may represent a therapeutic avenue to modulate microglia after TBI.

Key words: adenosine, A1 receptor, BV-2 cells, head injury, Iba-1, knockout, microglia, neurotrauma

Introduction

We previously reported that adenosine A1 receptor (A1AR) knockout (KO) mice develop lethal status epilepticus after experimental traumatic brain injury (TBI), a finding not seen in wild-type (WT) mice (Kochanek et al., 2006). This finding was consistent with the known propensity for post-traumatic seizures after experimental TBI (Golarai et al., 2001) and the purported crucial role of A1AR in keeping an epileptic focus localized (Fedele et al., 2006). Rapid mortality in these mice, however, precluded the ability to study appropriately the neuropathological consequences of this injury.

The role of A1AR in the evolution of neuronal death, as studied with A1AR agonists and antagonists, is complex. After inducing TBI by controlled cortical impact (CCI) in mice, Varma and associates (2002) reported that local injection of the highly selective A1AR agonist 2-chloro-N-cyclopentyladenosine (CCPA) attenuated neuronal loss in CA3, but not CA1. Neither the A1AR agonist CCPA nor the highly selective A1AR antagonist 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (DPCPX), however, affected cortical lesion volume. Use of A1AR KO mice in other brain injury models has yielded conflicting results. Olsson and associates (2004) reported that deletion of the A1AR did not alter neuronal damage in a mouse model of global cerebral ischemia, despite the fact that administration of an A1AR antagonist, 8-cyclopentyltheophylline, in naïve WT mice, exacerbated the damage. In contrast, Fedele and colleagues (2006) reported marked exacerbation of neuronal damage after kainic acid-induced status epilepticus in A1AR KO versus WT mice.

Adenosine is not only an inhibitory neuromodulator, but also an immunomodulator in the brain (reviewed in Daré et al., 2007). Newby (1984) described adenosine as a “retaliatory metabolite” that is released in response to injury and affects immune function so as to protect against excessive inflammation. Adenosine, through effects at A1, A2A, and A3 receptors, can have immunomodulatory effects on microglial proliferation and function in culture (Hammarberg et al., 2003; Si et al., 1996). Si and associates (1996) reported that non-selective and selective A1AR agonists, but not A2AR agonists, attenuated proliferation of rat microglia stimulated by phorbol. Recent studies using A1AR KO mice in experimental allergic encephalitis (EAE) and neuro-oncology models suggested substantively enhanced neuroinflammation in the KO (Tsutsui et al., 2004). Specifically, A1AR KO mice showed increased proinflammatory gene expression, demyelination, and microglial proliferation versus WT. Enhanced microglial proliferation and enhanced tumor growth were also observed in A1AR KO mice versus WT after implantation of experimental glioblastoma cells (Synowitz et al., 2006).

We hypothesized that A1AR deficiency would exacerbate neuronal damage and the microglial response after experimental TBI in mice. To test this hypothesis, we reduced the injury level in the CCI model to a threshold below the acute seizure threshold in A1AR KO mice, and studied neuropathology and Iba-1 immunostaining after the injury. To further explore the role of A1AR in regulating microglial proliferation, we studied the effect of A1AR agonists and antagonists on 3H-thymidine incorporation (an index of cell proliferation) by cultured BV-2 cells (a widely used immortalized mouse microglial cell line).

Methods

Animals

All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, PA). A1AR KO mice were generated as previously described (Kochanek et al., 2006). Heterozygous pairs were bred at our facility and generated homozygous WT, homozygous KO, and heterozygous offspring. Genotypes were determined using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on tail deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). Polymerase chain reaction was performed at cycling temperatures of 94°C, 3 min, 30 cycles of 94°C, 58°C, 72°C each 1 min, and 72°C, 8 min. Primer pairs for genotyping were described previously by Sun and associates (2001). Products were separated on 1% agarose gel with 0.5% ethidium bromide and visualized under ultraviolet light.

CCI model

Mixed gender A1AR KO and WT littermate mice at 12 to 22 weeks of age were subjected to CCI as previously described (Kochanek et al., 2006; Sinz et al., 1999) with important modifications as described below. In brief, mice were anesthetized with 4% isoflurane in N2O/O2 (2:1) by nose cone and placed in a stereotactic frame. Isoflurane was reduced to 2% after positioning. Brain temperature was continuously monitored by a microprobe inserted through a burr hole in the left frontal cortex. Brain temperature and rectal temperature were maintained at 37 ± 0.5°C. A 5 mm craniotomy was performed over the left parietal-temporal cortex and the bone flap was removed. Because our standard injury level in the model produced a high rate of lethal status epilepticus in A1KO mice (Kochanek et al., 2006), the injury level was reduced to a velocity of 3 m/sec at a depth of 0.5 mm. Pilot studies revealed that this was the highest injury level that was below the threshold for inducing acute seizures in the A1AR KO mouse in our laboratory. The bone flap was replaced and sealed with dental cement and the scalp was sutured closed. Anesthesia was discontinued and the mice were placed in an oxygen hood for 30 min before being returned to their cages. Identical protocols were performed on both WT and KO mice. In addition, naïve control A1AR KO and WT mice were also studied to assess baseline immunostaining. In shams, surgery (including craniotomy), anesthesia, and 7 day recovery were identical to injured mice except that CCI was not performed.

Assessment of Iba-1 immunostaining

At 7 days after CCI, mice were anesthetized with 4% isoflurane in N2O/O2 (2:1) and transcardially perfused with 50 mL heparinized saline and 50 mL 10% buffered formalin. Brains were removed and cryoprotected in 15% and 30% sucrose and then frozen in liquid nitrogen. Brain sections (10 μm) were taken through the lesion at the level of the dorsal hippocampus (between 2.5 and 3.0 mm from the occiput) to quantify microglia. Sections were stained with Iba-1 antibody (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA), a microglia-specific antigen (Ito et al., 2001). In brief, sections were washed in 1× PBST for 15 min, blocked with 5% normal goat serum in PBST for 1 h, and then incubated in IBA-1 antibody (1:250) overnight at 4°C. After 3 PBST washes, sections were incubated for 1 h in FITC conjugated goat-anti rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:500). A representative brain section from each mouse was evaluated for Iba-1 staining in the CA1 and CA3 regions of the hippocampus, peri-contusional cortex, and dorsal thalamus, both ipsilateral and contralateral to the injury. Each brain section was photographed at 200 × with an exposure time of 5.7 sec. The number of activated microglia in Iba-1-stained sections was quantified by a blinded observer (MLH) using Image-J (NIH, Bethesda, MD) with a size threshold of 100 pixels, a value previously determined to produce results most consistent with manual cell counting.

Assessment of neuronal injury by Fluoro-Jade C staining in CA1 and CA3 hippocampus

A separate group of mice were sacrificed at 24 h via transcardial perfusion with 50 mL of heparinized saline and 50 mL of 10% buffered formalin. Brains from these mice were removed, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. 5 μm sections were taken through the lesion at the level of the dorsal hippocampus (between −2.30 mm and −1.94 mm from bregma) and stained with Fluoro-Jade C (FJC, Chemicon, Temecula, CA) as previously described (Fink et al., 2004) to probe for acute neuronal degeneration. All sections were assessed qualitatively for FJC-positive neurons in CA1 and CA3 by light microscopy using a Nikon Eclipse E600 (Tokyo, Japan).

Analysis of brain tissue volumes

At 7 days after CCI, mice were anesthetized with 4% isoflurane in N2O/O2 (2:1) and transcardially perfused with 50 mL of heparinized saline and 50 mL of 10% buffered formalin. Brains were removed and cryoprotected in 15% and 30% sucrose and then frozen in liquid nitrogen. Each brain was sectioned in its entirety from caudal to rostral at intervals of 0.5 mm. Four 10 μm sections were obtained at each interval and stained with cresyl violet for lesion volume analysis. Sections were evaluated by a blinded observer (MLH), and grossly intact tissue, quantified as cortical areas in each section, was recorded using the MCID imaging system (MCID Imaging Research, St. Catherines, CA). For each brain interval a mean of all four sections was used to assess both the hemisphere contralateral and ipsilateral to injury for hemispheric and cortical areas. The mean of each interval was summed and multiplied by the interval length (0.5 mm) to calculate a volume for each of the areas listed above. From each of the calculated volumes a percent difference (contralateral minus ipsilateral) was also derived. In addition, the injured cortex was further assessed by taking an additional measurement that excluded those areas containing tissue, but with obvious loss of staining, and considered them part of the lesion. The resultant volumes quantifying tissue with normal staining intensity (reflecting even greater tissue loss in injured cortex) were then calculated using the same method as described above.

Effects of adenosine agonists and antagonists on 3H-thymidine incorporation in cultured BV-2 cells

We employed BV-2 cells, a widely used immortalized mouse microglial cell line. The BV-2 cell line was created from murine primary microglial cultures by transformation with the J2 retrovirus carrying a v-raf/v-myc oncogene (Blasi et al., 1990). BV-2 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Martin Mornsard (University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland). BV-2 cells were grown to subconfluence in DMEM medium in 24-well culture plates. Before treatments, BV-2 cells were growth arrested for 24 h by reducing the concentration of fetal calf serum from 10% to 0.3%, and then proliferation was initiated by treating growth-arrested cells for 20 h with DMEM medium supplemented with fetal calf serum (FCS; 2.5%) and containing or lacking the various treatments (Table 1) or their vehicles. After 20 h of incubation, treatments were repeated with freshly prepared solutions but supplemented with 3H-thymidine (1 μCi/mL) for an additional 4 h. The experiments were terminated by washing the cells twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and twice with ice-cold trichloroacetic acid (TCA, 10%). The precipitate was solubilized in 500 μL of 0.3 N NaOH and 0.1% sodium dodecylsulfate after incubation at 50°C for 2 h. Aliquots from each culture well were added to 10 mL of scintillation fluid and were counted in a liquid scintillation counter.

Table 1.

Adenosine Receptor Agonists and Antagonists Used in BV-2 Cells

| Compound | Abbreviation | Type of pharmacological probe | Receptor selectivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine | CCPA | Agonist | A1AR |

| 2-p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenethylamino-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (aka CGS 21860) | CGS | Agonist | A2AAR |

| 2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide | Cl-IB-MECA | Agonist | A3AR |

| 5′-(N-ethylcarboxamido)adenosine | NECA | Agonist | Non-selective |

| 2-chloroadenosine | 2-CADO | Agonist | Non-selective |

| 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine | DPCPX | Antagonist | A1AR |

| 7-(2-phenylethyl)-5-amino-2-(2-furyl)-pyrazolo-[4,3-e]-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidine (aka SCH 58261) | SCH | Antagonist | A2AAR |

| 8-[4-[((4-cyanophenyl)carbamoylmethyl)oxy]phenyl]-1,3-di(n-propyl)xanthine (aka MRS 1754) | MRS | Antagonist | A2BAR |

| N-(2-Methoxyphenyl)-N′-[2-(3-pyridinyl)-4-quinazolinyl]-urea (aka VUF 5574) | VUF | Antagonist | A3AR |

Quantitative real-time PCR of adenosine receptor mRNA expression in cultured BV-2 cells

Total RNA was isolated from subconfluent BV-2 cells using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was synthesized using iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time PCR assay was performed with the primers (Table 2) by using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in the AB 7300 Real-time PCR System. The threshold cycle (Ct) for target was subtracted from the Ct for β-actin to calculate ΔCt, and relative mRNA levels were expressed as 2ΔCt as recommended by Varma and Cheng (2008).

Table 2.

Primers Used for Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis of Adenosine Receptor mRNA Levels in BV-2 Cells

| Protein | Real-time PCR forward primer sequence (5′-3′) | Real-time PCR reverse primer sequence (5′-3′) | Base pair size of amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | actcttccagccttccttc | atctccttctgcatcctgtc | 171 |

| A1AR | agaaccacctccacccttct | tactctgggtggtggtcaca | 227 |

| A2AAR | tcaacagcaacctgcagaac | ggctgaagatggaactctg | 186 |

| A2BAR | gcgaataaaagctgctgtcc | cctggagtggtccatcagtt | 186 |

| A3AR | gttccgtggtcagtttggat | gcgcaaacaagaagagaacc | 216 |

Statistical analysis

Individual comparisons between A1AR KO and WT groups were made using Student's t test. Multiple comparisons between groups were made using one-way analysis of variance and appropriate post-hoc tests, corrected for multiple comparisons. All values are presented as mean ± standard error.

Results

A total of 51 A1AR KO and 35 WT littermate mice were subjected to mild CCI. Shams (n = 3 per genotype) were also studied. The mortality rate was 31.4% in the KO and 0% in WT. No mice died in the acute post-injury period. Rather, the mice of both genotypes appeared to recover normally from anesthesia. Despite generally vigorous appearance, mortality occurred over several days post-trauma, with some KO mice dying in their cages between 1 and 7 days after injury. Body weight did not differ between A1AR KO and WT (27.10 ± 0.60 vs. 26.80 ± 0.47 g, NS, respectively).

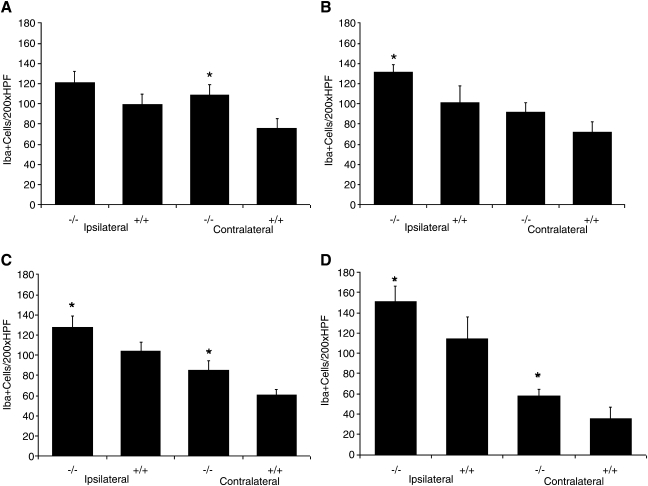

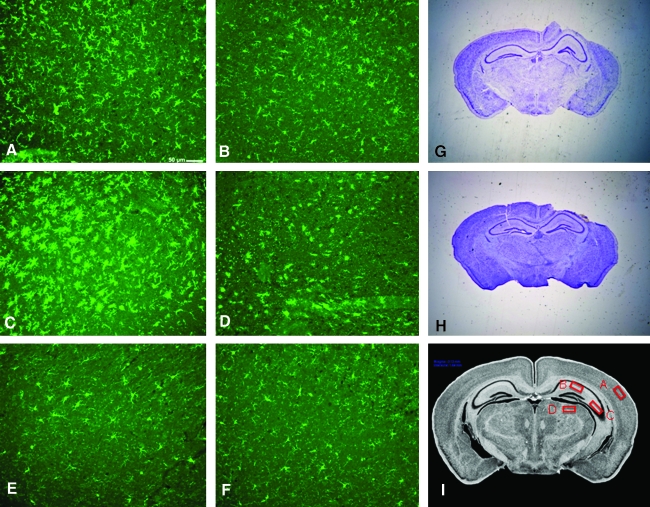

Iba-1 staining in A1AR KO was significantly greater than in WT in six of the eight brain regions examined including ipsilateral CA3, cortex, and thalamus, and contralateral CA1, cortex, and thalamus (all p < 0.05, Fig. 1). Even in those regions not reaching significance in KO versus WT, trends toward greater Iba-1 immunostaining were observed in KO (Fig. 1). Representative examples of Iba-1 immunostaining in A1AR KO and WT are shown in Figure 2A–D. TBI induced a marked microglial response as reflected by the clear difference between respective sections from the hemispheres ipsilateral and contralateral to injury and when compared to naïve animals. Iba-1 immunostaining in brain sections from naïve A1AR KO and WT revealed low levels of staining in all brain regions in the absence of injury. Representative examples are shown in Figure 2E,F. There was no significant difference (p < 0.05) in Iba-1 immunostaining (number of Iba-1 positive cells per 200× high-power field) in sham A1AR KO versus WT in any region (Table 3). In addition, Iba-1 levels were 3- to 10-fold higher in injured mice than in corresponding shams, in every brain region, which reflected the anticipated low baseline level of Iba-1 immunoreactivity (Ito et al., 2001).

FIG. 1.

Iba-1 positive cell counts per 200 × HPF across multiple brain regions at 7 days after experimental traumatic brain injury. (A) CA1 hippocampus, adenosine A1-receptor (A1AR) knockout (KO) (−/−, n = 13; 8 male, 5 female) versus wild-type (WT) (+/+, n = 8; 4 male, 4 female), (B) CA3 hippocampus, (C) cortex, (D) thalamus. Iba-1 staining identified activated microglia in A1AR KO that was robust and significantly greater than in WT in six of the eight brain regions examined including ipsilateral CA3, cortex, and thalamus, and contralateral CA1, cortex, and thalamus. Even in those regions not reaching significance in A1AR KO versus WT, trends toward greater Iba-1 immunostaining were observed in A1AR KO. *p < 0.05.

FIG. 2.

Representative images of Iba-1 and cresyl violet stained brain sections. (A) A1-receptor (A1AR) knockout (KO) ipsilateral cortex—Iba-1, post-traumatic brain injury (TBI). (B) Wild-type (WT) ipsilateral cortex—Iba-1, post-TBI. (C) A1AR KO ipsilateral thalamus—Iba-1, post-TBI. (D) WT ipsilateral thalamus—Iba-1, post-TBI. (E) A1AR KO ipsilateral cortex—Iba-1, naïve. (F) WT ipsilateral cortex—Iba-1, naïve. (G) A1AR KO—cresyl violet, post-TBI. (H) WT—cresyl violet, post-TBI. Iba-1 staining demonstrates a significant and diffuse increase in the microglial response to TBI in A1AR KO versus WT mice (A–F). In contrast, no obvious difference in lesion volume is appreciated between A1AR KO and WT mice (G, H). (I) Sampling for quantification of Iba-1 immunostaining.

Table 3.

Microglia as Assessed by Iba-1 Immunostaining in Sham A1AR KO and WT Mice

| Brain structure | A1AR KO | WT | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA1 | 29.00 ± 6.66a | 24.67 ± 4.06 | 0.61 |

| CA3 | 24.00 ± 9.64 | 14.67 ± 3.84 | 0.42 |

| Cortex | 37.67 ± 10.37 | 21.00 ± 3.51 | 0.20 |

| Thalamus | 23.33 ± 10.84 | 12.00 ± 4.04 | 0.38 |

A1AR, adenosine A1 receptor; KO, knockout; WT, wild type.

Mean ± SEM.

Comparison between genotypes by two-tailed t-test; n = 3 per genotype.

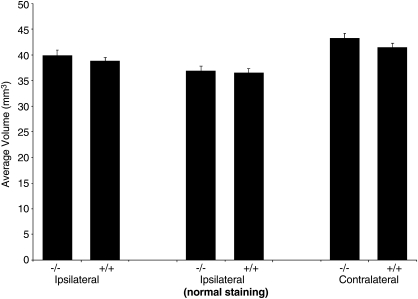

Fluoro-Jade C positive neurons were not detected in any brain section in either CA1 or CA3 hippocampus at this mild injury level at 24 h after CCI in either A1AR KO or WT mice (data not shown). Cortical volumes at 7 days after injury did not differ between A1AR KO and WT in either the injured or contralateral hemispheres (Fig. 3), a finding that was observed regardless of whether the analysis was based on overt tissue loss or abnormal tissue staining (see Methods section). Comparison of percent differences between contralateral and ipsilateral cortical volumes indicated that this mild injury level resulted in loss of ∼7% of the cortex in the hemisphere ipsilateral to injury. Percent differences between contralateral and ipsilateral cortical volumes also did not differ between KO and WT. Representative examples of cresyl violet staining of brain sections in A1AR KO and WT are shown in Figure 2G, H.

FIG. 3.

Cortical volume at 7 days after traumatic brain injury (TBI) did not differ significantly between A1-receptor (A1AR) knockout (KO) (−/−, n = 18; 9 male, 9 female) versus wild-type (WT) (+/+, n = 17; 9 male, 8 female) mice in either the injured or contralateral hemispheres, regardless of quantification method used (see Methods section).

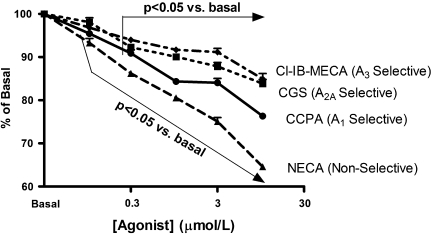

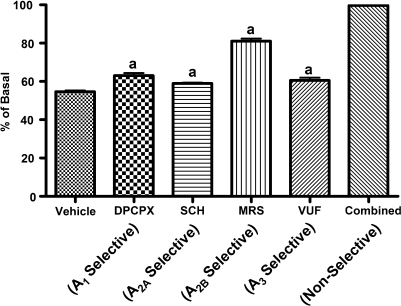

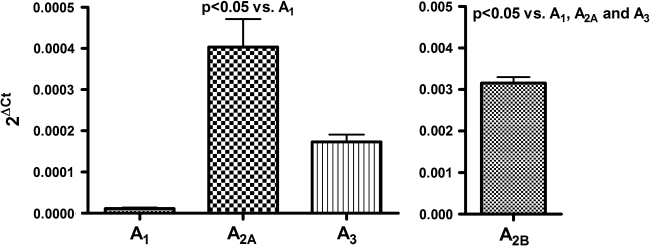

In BV-2 cells the highly selective A1AR agonist CCPA inhibited 3H-thymidine incorporation in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4). Although the highly selective A2AAR agonist CGS and the highly selective A3AR agonist Cl-IB-MECA also caused concentration-related decreases in 3H-thymidine incorporation by BV-2 cells, these compounds were less potent in this regard compared with CCPA (Fig. 4). NECA, a compound that activates A1ARs, A2AARs, A2BArs, and A3ARs, was even more potent as an inhibitor of BV-2 proliferation than was CCPA, CGS, or CL-IB-MECA (Fig. 4). 2-CADO (1 μM), a non-selective activator of A1ARs, A2AARs, A2BArs, and A3ARs, also profoundly inhibited 3H-thymidine incorporation by BV-2 cells (Fig. 5), and this response was reversed partially by DPCPX (100 nM; A1AR selective antagonist), SCH (100 nM; A2AAR selective antagonist), MRS (100 nM; A2BAR selective antagonist), and VUF (100 nM; A3AR selective antagonist) (Fig. 5). Combined, the antagonists completely reversed the inhibitory effects of 2-chloroadenosine (Fig. 5). As shown in Figure 6, mRNA for all four adenosine receptors was detected in BV-2 cells in the following order of abundance: A2BARs > A2AARs ≈ A3ARs > A1ARs.

FIG. 4.

The effects of adenosine receptor agonists on 3H-thymidine incorporation in BV-2 cells. BV-2 cells were treated for 24 h with the indicated concentrations of one of four different agonists and pulsed with 3H-thymidine during the last 4 h of incubation. The graph shows 3H-thymidine incorporation normalized to a well (basal) on the same culture plate that received no treatment. Statistical analyses were performed on absolute 3H-thymidine incorporation. The overall p value for the effect of each agonist by analysis of variance was p < 0.000001. P values are for multiple comparisons tests compared with basal. Values are means and SEMs for n = 6.

FIG. 5.

The effects of the non-selective adenosine receptor agonist 2-CADO (1 μM) on 3H-thymidine incorporation in BV-2 cells in the absence (vehicle) and presence of selective adenosine receptor antagonists (either DPCPX, SCH, MRS, or VUF; all at 0.1 μM). BV-2 cells were treated for 24 h without or with 2-CADO and without or with the indicated antagonists and pulsed with 3H-thymidine during the last 4 h of incubation. The graph shows the effects of 2-CADO on 3H-thymidine incorporation normalized to a well (basal) on the same culture plate that was not treated with 2-CADO but did receive either the vehicle for the antagonists or one of the antagonists. The antagonists per se did not alter basal 3H-thymidine incorporation. Statistical analyses were performed on percent of basal, and the overall p value for the effect of the antagonists by analysis of variance was p < 0.000001. ap < 0.05 compared with vehicle (multiple comparisons tests). Values are means and SEMs for n = 6.

FIG. 6.

mRNA expression for adenosine receptor subtypes using quantitative real-time PCR. Left panel is for A1, A2A, and A3 receptor mRNA (scale 0–0.0005) and right panel is for A2B receptor mRNA (scale 0–0.005). Threshold cycle (Ct) for target mRNA was subtracted from the Ct for β-actin mRNA to calculate ΔCt, and relative mRNA levels were expressed as 2ΔCt as recommended by Varma and Cheng (2008). The overall p value from analysis of variance was p < 0.000001. P values in graph are for multiple comparisons tests. Values are means and SEMs for n = 9.

Discussion

Our results provide three lines of evidence that A1AR activation serves as an important brake on the microglial response to TBI: (1) at 7 days after CCI, Iba-1 immunostaining is enhanced in the A1AR KO in most brain regions; (2) in mouse microglial culture, proliferation, as assessed by 3H-thymidine incorporation, is inhibited by CCPA, a highly-selective A1AR agonist; and (3) in mouse microglial culture, inhibition of proliferation by the non-selective adenosine receptor agonist 2-CADO is partially reversed by DPCPX, a highly-selective A1AR antagonist.

Two prior studies in CNS inflammation models have shown increases in microglial proliferation in A1AR KO versus WT mice (Synowitz et al., 2006; Tsutsui et al., 2004). In EAE, A1AR KO mice have enhanced microglial proliferation that is accompanied by increased damage and proinflammatory gene expression in spinal cord. Synowitz and associates (2006) report increased microglial proliferation after implantation of glioblastoma tumor cells in A1AR KO vs WT. Thus, A1AR activation may attenuate the microglial response across insults. Tsutsui and colleagues (2004) also report that bone marrow-derived macrophages from A1AR KO mice show enhanced proinflammatory gene expression after LPS stimulation. Macrophages also accumulate in brain after CCI (Bayir et al., 2005; Foley et al., 2009; Tong et al., 2002). The role of the A1AR in regulating the microglial versus macrophage response in TBI remains to be defined.

Si and associates (1996) report inhibition of phorbol-stimulated proliferation of rat microglia by nonselective and A1AR-specific agonists. However, the effects of A1AR activation on microglial proliferation in culture are complex. Gebicke-Haerter and associates (1996) report that simultaneous administration of A1AR and A2AR agonists elicited microglial proliferation rather than its inhibition in unstimulated rat microglia while Wollmer and associates (2001) report no effect of the A1AR agonist CPA on proliferation of unstimulated rat microglia. It is likely necessary to stimulate proliferation in order to observe inhibition of proliferation with AR agonists.

Our cell culture findings suggest that A1ARs inhibit microglial proliferation, as indicated by the potent effects of CCPA and DPCPX. Nonetheless, other adenosine receptor subtypes also inhibit proliferation. Although the effects of the A2AAR and A3AR are modest, the A2BAR potently inhibits growth as indicated by (1) large effects of the non-selective adenosine receptor agonist NECA and (2) reversal of the effects of 2-CADO by the selective A2BAR antagonist MRS. Thus, it would be of interest to study microglial proliferation after TBI in A2BAR KO mice.

The roles of the various adenosine receptor subtypes likely depend on their relative expression. In BV-2 cells, despite the fact that the expression of A1AR mRNA is ∼1/10th that of the A2AAR and A3AR and 1/100th that of the A2BAR, the A1AR makes a major contribution to the inhibitory effects of 2-CADO. A1ARs are thus potent inhibitors of microglial proliferation because of their high affinity. It is conceivable that immortalization of microglia to generate the BV-2 cell line suppresses A1AR expression. It would be important to determine the relative roles of adenosine receptors in cell proliferation of primary microglia.

We are surprised to observe that the enhanced microglial response is seen in brain structures ipsilateral and contralateral to the injury, although the response is greater ipsilateral to the injury. This supports the work of Hall and associates (2005, 2008) who report bilateral fiber degeneration after CCI in mice. The global microglial response in A1AR KO mice suggests that even after a mild CCI with no hippocampal neuronal death, a low level of diffuse fiber degeneration may represent the stimulus for this response; further studies are needed.

Given the exacerbation of damage observed by Fedele and co-workers (2006) in A1AR KO mice treated with kainate, it is surprising that we do not observe greater neuropathological injury in KO versus WT mice. However, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that A1AR KO mice could have increased damage after CCI. Varma and associates (2002), using a much more severe injury level than in the current study, showed that parenchymal injection of the selective A1AR agonist CCPA after CCI in mice reduced neuronal death, but only in CA3. The important role of A1AR in hippocampus may make that region more amenable to A1AR agonist or antagonist treatment than the cortex (Gimémez-Llort et al., 2005; Gundlfinger et al., 2007). Fedele and associates (2006) noted exacerbation of damage after kainate injection in A1AR KO mice in hippocampus. Since seizures and hippocampal excitation are linked after TBI (Golarai et al., 2001), and that seizures exacerbate anoxia-induced neuronal death in hippocampus (Dzhala et al., 2000), it may be difficult to establish an injury level producing sufficient vulnerability in CA1 or CA3 without precipitating status epileptics and death in the A1AR KO. Even using this very mild CCI, 31% delayed mortality is seen in A1AR KO versus 0% in WT. Nevertheless, we do not detect FJC + neurons. Another strategy to define the role of A1ARs in CCI would be to use a more severe injury and treat mice with an anti-convulsant. We cannot rule out a compensatory effect of A1AR deficiency, as suggested by Olsson and colleagues (2004), who report that CA1 neuronal death after brain ischemia is not increased in the A1AR KO.

Although there is a body of support for a deleterious role of microglia in brain injury (Lai and Todd, 2006), a beneficial role is also possible and may depend on the insult, timing, and other factors. Lalancette-Hébert and colleagues (2007) showed the neuroprotective potential of microglia in focal cerebral ischemia. It is tempting to speculate that the enhanced microglial proliferation in A1AR KO is neuroprotective and accounts for the lack of increased neuronal damage versus WT.

Tsutsui and co-workers (2004) show that chronic treatment with the non-selective A1AR antagonist caffeine upregulates A1AR on microglia and abrogates damage in EAE. Li and colleagues (2008) report that chronic, but not acute, treatment with caffeine attenuates brain edema and leukocyte influx in mice after TBI. These findings take on greater significance given the recent report of an association between increased levels of caffeine in cerebrospinal fluid and favorable outcomes in humans after TBI (Sachse et al., 2008). Thus, the potential benefit of caffeine in TBI may be mediated by anti-inflammatory effects of A1AR upregulation. Given the ubiquitous nature of caffeine use (Strong et al., 2000), further study is warranted.

There are several limitations of this work. Microglial proliferation, activation, and migration are regulated differentially (Hanisch and Kettenmann, 2007), and we did not distinguish between them in our in vivo work. Upregulation of Iba-1 could contribute to our in vivo findings. Also, we did not define the contributions of microglia versus macrophages. We did not characterize a complete time course, although 7 days after TBI is a good target for proof-of-concept. Iba-1 is only one of many microglial markers that could be used. Finally, we cannot rule out a possible role for non-convulsive seizures or status epilepticus in mediating both the microgial response (Avignone et al., 2008) and mortality after mild CCI. Lai and Todd (2006) report that glutamate can stimulate microglial proliferation, and we cannot rule out glutamate release in mediating this process.

We conclude A1AR KO mice exhibit an enhanced microglial response after CCI, although neuronal damage was not increased. A1AR activation may represent an endogenous inhibitor of microglial proliferation and possibly a new therapeutic avenue to manipulate this aspect of neuro-inflammation in TBI.

Acknowledgments

We thank NIH NS 38087 (PMK), NS 30318 (PMK), DK 068575 (EKJ), Swiss National Science Foundation #32-64040.00 (RKD), 320000-117998 (RKD), and Oncosuisse OCS-01551-08-2004 (RKD) for support. We thank Marci Provins and Cara Mulhollen for assisting with manuscript preparation.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Avignone E. Ulmann L. Levavasseur F. Rassendren F. Audinat E. Status epilepticus induces a particular microglial activation state characterized by enhanced purinergic signaling. J. Neuroscience. 2008;28:9133–9144. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1820-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayır H. Kagan V.E. Borisenko G.G. Tyurina Y.Y. Janesko K.L. Vagni V.A. Billiar T.R. Williams D.L. Kochanek P.M. Enhanced oxidative stress in iNOS-deficient mice after traumatic brain injury: support for a neuroprotective role of iNOS. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:673–684. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi E. Barluzzi R. Bocchini V. Mazzolla R. Bistoni F. Immortalization of murine microglial cells by a v-raf/v-myc carrying retrovirus. J. Neuroimmunol. 1990;27:229–237. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(90)90073-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daré E. Schulte G. Karovic O. Hammarberg C. Fredholm B.B. Modulation of glial cell functions by adenosine receptors. Physiol. Behav. 2007;92:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzhala V. Ben-Ari Y. Khazipov R. Seizures accelerate anoxia-induced neuronal death in the neonatal rat hippocampus. Ann. Neurol. 2000;48:632–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele D.E. Li T. Lan J.Q. Fredholm B.B. Boison D. Adenosine A1 receptors are crucial in keeping an epileptic focus localized. Exp. Neurol. 2006;200:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.02.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink E.L. Alexander H. Marco C.D. Dixon C.E. Kochanek P.M. Jenkins L.W. Lai Y. Donovan H.A. Hickey R.W. Clark R.S. Experimental model of pediatric asphyxial cardiopulmonary arrest in rats. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2004;5:139–144. doi: 10.1097/01.pcc.0000112376.29903.8f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley L.M. Hitchens T.K. Ho C. Janesko-Feldman K.L. Melick J.A. Bayır H. Kochanek P.M. Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of macrophage accumulation in mouse brain after experimental traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1509–1519. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebicke-Haerter P.J. Christoffel F. Timmer J. Northoff H. Berger M. Van Calker D. Both adenosine A1- and A2-receptors are required to stimulate microglial proliferation. Neurochem. Int. 1996;29:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giménez-Llort L. Masino S.A. Diao L. Fernández-Teruel A. Tobeña A. Halldner L. Fredholm B.B. Mice lacking the adenosine A1 receptor have normal spatial learning and plasticity in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, but they habituate more slowly. Synapse. 2005;57:8–16. doi: 10.1002/syn.20146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golarai G. Greenwood A.C. Feeney D.M. Connor J.A. Physiological and structural evidence for hippocampal involvement in persistent seizure susceptibility after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:8523–8537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08523.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundlfinger A. Bischofberger J. Johenning F.W. Torvinen M. Schmitz D. Breustedt J. Adenosine modulates transmission at the hippocampal mossy fibre synapse via direct inhibition of presynaptic calcium channels. J. Physiol. 2007;582:263–277. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.132613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall E.D. Bryant Y.D. Cho W. Sullivan P.G. Evolution of post-traumatic neurodegeneration after controlled cortical impact traumatic brain injury in mice and rats as assessed by the de Olmos silver and fluorojade staining methods. J. Neurotrauma. 2008;25:235–247. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall E.D. Sullivan P.G. Gibson T.R. Pavel K.M. Thompson B.M. Scheff S.W. Spatial and temporal characteristics of neurodegeneration after controlled cortical impact in mice: more than a focal brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2005;22:252–265. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarberg C. Schulte G. Fredholm B.B. Evidence for functional adenosine A3 receptors in microglia cells. J. Neurochem. 2003;86:1051–1054. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch U.K. Kettenmann H. Microglia: active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:1387–1394. doi: 10.1038/nn1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito D. Tanaka K. Suzuki S. Dembo T. Fukuuchi Y. Enhanced expression of lba1, ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1, after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rat brain. Stroke. 2001;32:1208–1215. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.5.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson K.A. Knutsen L.J.S. P1 and P2 purine and pyrimidine receptor ligands. In: Abbracchio M.P., editor; Williams M M., editor. Purinergic and Pyrmidinergic Signalling I. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2001. pp. 129–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanek P.M. Vagni V.A. Janesko K.L. Washington C.B. Crumrine P.K. Garman R.H. Jenkins L.W. Clark R.S. Homanics G.E. Dixon C.E. Schnermann J. Jackson E.K. Adenosine A1 receptor knockout mice develop lethal status epilepticus after experimental traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:565–575. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai A.Y. Todd K.G. Microglia in cerebral ischemia: molecular actions and interaction. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2006;84:49–59. doi: 10.1139/Y05-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalancette-Hébert M. Gowing G. Simard A. Weng Y.C. Kriz J. Selective ablation of proliferating microglial cells exacerbates ischemic injury in the brain. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:2596–2605. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5360-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. Dai S. An J. Li P. Chen X. Xiong R. Liu P. Wang H. Zhao Y. Zhu M. Liu X. Zhu P. Chen J.F. Zhou Y. Chronic but not acute treatment with caffeine attenuates traumatic brain injury in the mouse cortical impact model. Neuroscience. 2008;151:1198–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newby A.C. Adenosine and the concept of retaliatory metabolites. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1984;9:42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson T. Cronberg T. Rytter A. Asztély F. Fredholm B.B. Smith M.L. Wieloch T. Deletion of the adenosine A1 receptor gene does not alter neuronal damage following ischaemia in vivo or in vitro. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;20:1197–1204. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachse K.T. Jackson E.K. Wisniewski S.R. Gillespie D.G. Puccio A.M. Clark R.S. Dixon C.E. Kochanek P.M. Increases in cerebrospinal fluid caffeine concentration are associated with favorable outcome after severe traumatic brain injury in humans. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:395–401. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si Q.S. Nakamura Y. Schubert P. Rudolphi K. Kataoka K. Adenosine and propentofylline inhibit the proliferation of cultured microglial cells. Exp. Neurol. 1996;137:345–349. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinz E.H. Kochanek P.M. Dixon C.E. Clark R.S. Carcillo J.A. Schiding J.K. Inducible nitric oxide synthase is an endogenous neuroprotectant after traumatic brain injury in rats and mice. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:647–656. doi: 10.1172/JCI6670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong R. Grotta J.C. Aronowski J. Combination of low dose ethanol and caffeine protects brain from damage produced by focal ischemia in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:515–522. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D. Samuelson L.C. Yang T. Huang Y. Paliege A. Saunders T. Briggs J. Schnermann J. Mediation of tubuloglomerular feedback by adenosine-evidence from mice lacking adenosine 1 receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:9983–9988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171317998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synowitz M. Glass R. Färber K. Markovic D. Kronenberg G. Herrmann K. Schnermann J. Nolte C. van Rooijen N. Kiwit J. Kettenmann H. A1 adenosine receptors in microglia control glioblastoma-host interaction. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8550–8557. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong W. Igarashi T. Ferriero D.M. Noble L.J. Traumatic brain injury in the immature mouse brain: characterization of regional vulnerability. Exp. Neurol. 2002;176:105–116. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui S. Schnermann J. Noorbakhsh F. Henry S. Yong V.W. Winston B.W. Warren K. Power C. A1 adenosine receptor upregulation and activation attenuates neuroinflammation and demyelination in a model of multiple sclerosis. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:1521–1529. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4271-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Muijlwijk-Koezen J.E. Timmerman H. van der Goot H. Menge W.M. Frijtag Von Drabbe Künzel J. de Groote M. Jizerman A.P. Isoquinoline and quinazoline urea analogues as antagonists for the human adenosine A3 receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:2227–2238. doi: 10.1021/jm000002u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma M.R. Dixon C.E. Jackson E.K. Peters G.W. Melick J.A. Griffith R.P. Vagni V.A. Clark R.S. Jenkins L.W. Kochanek P.M. Administration of adenosine receptor agonists or antagonists after controlled cortical impact in mice: effects on function and histopathology. Brain Res. 2002;951:191–201. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03161-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vespa P.M. Miller C. McArthur D. Eliseo M. Etchepare M. Hirt D. Glenn T.C. Martin N. Hovda D. Nonconvulsive electrographic seizures after traumatic brain injury result in a delayed, prolonged increase in intracranial pressure and metabolic crisis. Crit. Care Med. 2007;35:2830–2836. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollmer M.A. Lucius R. Wilms H. Held-Feindt J. Sievers J. Mentlein R. ATP and adenosine induce ramification of microglia in vitro. J. Neuroimmunol. 2001;115:19–27. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]