Abstract

In the last several years, multiple lines of evidence have suggested that the COP9 signalosome (CSN) plays a significant role in the regulation of multiple cancers and could be an attractive target for therapeutic intervention. First, the CSN plays a key role in the regulation of Cullin-containing ubiquitin E3 ligases that are central mediators of a variety of cellular functions essential during cancer progression. Second, several studies suggest that the individual subunits of the CSN, particularly CSN5, might regulate oncogenic and tumor suppressive functions independently of, or coordinately with, the CSN holocomplex. Thus, deregulation of CSN subunit function can have a dramatic effect on diverse cellular functions, including the maintenance of DNA fidelity, cell cycle control, DNA repair, angiogenesis, and microenvironmental homeostasis that are critical for tumor development. Additionally, clinical studies have suggested that the expression or localization of some CSN subunits correlate to disease progression or clinical outcome in a variety of tumor types. Although the study of CSN function in relation to tumor progression is in its infancy, this review will address current studies in relation to cancer initiation, progression, and potential for therapeutic intervention.

Cullin-Based E3s and Cancer

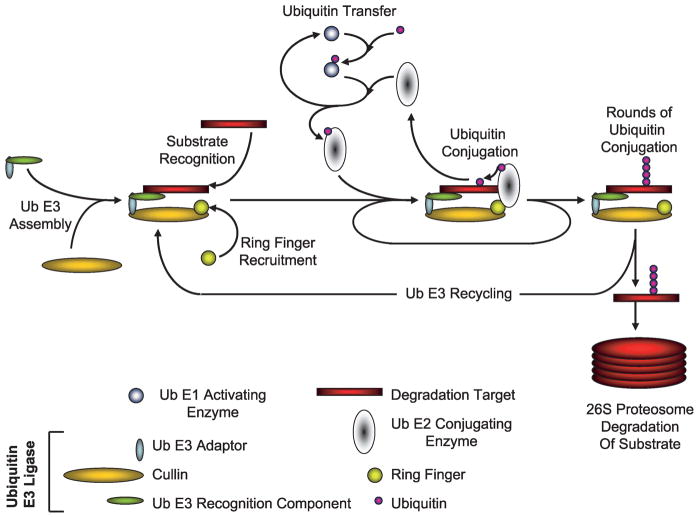

Before one can appreciate the scope in which the COP9 signalosome (CSN) can regulate tumorigenic processes, it is essential to briefly discuss the protein complexes that they regulate. Cullins are scaffold proteins that serve as assembly centers for the recognition components of a large variety of ubiquitin E3 ligases and their cognate ubiquitin E2 enzymes (Fig. 1; reviewed in refs. 1, 2). Cullins can be post-translationally modified on a conserved lysine via an isopeptide bond to the small protein Nedd8 in a manner similar to ubiquitin conjugation. This “neddylation” is thought to be required for the assembly of the ubiquitin E3-substrate complex and the ubiquitin-conjugated E2.

FIGURE 1.

The Cullin-containing ubiquitylation cycle.

Cullins are required for the degradation of key proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressors; therefore, a major goal for cancer biology will be to determine how this regulation becomes altered during tumorigenesis (3). There are seven Cullins expressed in humans that potentially couple to a large number of different E3 recognition components, although only a few of these complexes have been studied in any detail. Indeed, just the recognition components in the F-box, BTB, and SOCS/BC families number ~600 in humans, suggesting that a significant portion of the proteome could be regulated by the CSN. Importantly, several of these Cullin-based E3s (Cul-E3) have major significance in multiple aspects of cancer initiation and progression that include DNA replication fidelity, cell cycle control, apoptosis, immune response, adhesion, motility, and angiogenesis (3). Other factors, such as gene amplification of Cul4A in 16% of primary breast cancers and potentially in several other tumors and evidence that 47% of primary breast cancers overexpress Cul4A, are indications of Cullin significance in oncogenesis (4, 5).

Genetic evidence in lower organisms also suggests that Cullins are major mediators of processes required for oncogenesis. For instance, loss-of-function mutations of Cullin-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans result in a shortened G1 phase and hyperplasia in all tissues (1–3). Cul1 is also required for correct cell cycle exit in the worm. Cul2 positively regulates the cell cycle in C. elegans and is expressed primarily in proliferating cells. Disruption of Cul2 expression induces G1 arrest of germ cells and deregulated mitotic chromosome condensation (1–3). Cul3 depletion in C. elegans results in abnormal microfilament and microtubule organization (1–3). Importantly, Cul4 maintains genomic stability by temporally restricting DNA replication licensing in C. elegans (1–3). Cul4 knockdown results in massive DNA re-replication and S-phase accumulation of the Cdt1 replication licensing factor, which is also a target of Cul1 E3s in mammals.

Multiple Cul-E3s are known to regulate the 26S-dependent destruction of both tumor suppressors and proto-oncogenes (Table 1). The regulation of Cul-E3 recognition of these proteins is predominantly dependent on post-translational modification(s) of the target protein (i.e., phosphorylation and prolyl hydroxylation) or the regulated expression of the Cul-E3 recognition component. As shown in Table 1, many key oncogenic/tumor suppressor pathways are currently known to be regulated by Cul-E3s, such as Rb/E2F, cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinase, Myc, Notch, β-catenin, nuclear factor-κB, transforming growth factor-β, p53, Hedgehog, growth factor receptors, and pVHL. Notably, these Cul-E3 targets are central mediators of cell proliferation, apoptosis, adhesion, DNA repair, and oxygen homeostasis critical for tumor growth. Thus, there is substantial genetic evidence from model organisms and human cell lines that establish the Cullins as key regulators of cellular processes central to tumor development.

Table 1.

Cullin-Regulated Proteins Associated with Cancer

| Cullin type | E3 recognition component (reference) | Relevant target for ubiquitylation during tumor development |

|---|---|---|

| Cullin 1 | Skp2 (14–19, 21–28) | p27KIP1, p57KIP2, p21WAF1, Rb-related p130, Cdt1, c-Myc, Orc1, B-myb, E2F1, cyclin D1, cyclin E, E7 |

| Cullin 1 | Fbw7/hCdc4 (20, 50, 56, 57, 59, 60) | Cyclin E, Notch1, Notch4 |

| Cullin 1 | TrCP (46, 47, 61–70) | IκBα, Cdc25A, SMAD4, β-catenin, Emi1, ATF4/CREB2, nuclear factor-κB/p105, nuclear factor-κB/p100, Discs large tumor suppressor, Wee1, SMAD3, SMAD4 |

| Cullin 1 | NIPA (48) | Cyclin B1 |

| Cullin 2 | pVHL (71–73) | HIF-1α, HIF-2α, Med8, Rpb1 |

| Cullin 2 | SOCS (74, 75, 100) | Tel-Jak2, Vav, IRS-1, IRS-2 |

| Cullin 3 | Keap1 (76) | Nrf2 |

| Cullin 3 | Cdl3Mel-26 (77) | Mei-1/katanin |

| Cullin 3 | Unknown (79, 80) | Cubitus interruptus, RhoBTB2 |

| Cullin 3 | Btb3p/Bpoz2 (78) | Unknown |

| Cullin 4A | DDB1 (81, 82) | DDB2, CSA |

| Cullin 4A | Unknown (83) | Cdt1 |

| Cullin 5 | ASB2 (84) | Unknown |

| Cullin 5 | E4orf6-E1B55k (85) | p53 |

COP9 Signalosome

The CSN was discovered in Arabidopsis over a decade ago and has been shown to comprise eight core subunits in mammals (6–9). These subunits bear remarkable homology to the 19S lid of the 26S proteasome and the translation initiation complex eIF3 and are currently postulated to play a largely undetermined role in protein degradation (reviewed in refs. 10–12). The CSN has been of considerable interest to cancer biologists and oncologists in recent years for several reasons. Perhaps most importantly, the CSN has been found to play a central and necessary role in the degradation of multiple proteins that are known regulators of disease progression in diverse cancers (Table 2). Although most of the proteins shown in Table 2 interact with the CSN5 subunit, it is unclear whether all these proteins are degradation targets or if they play other roles in modulating undetermined CSN subunit functions [i.e., PGP9.5, migration inhibitory factor (MIF), and TRC8]. These data are further supported in knockout/mutational studies in a variety of organisms that suggest that the CSN is involved in pleiotropic functions (including cell cycle progression, radiation sensitivity, genome stability, and cell survival) that largely overlap known Cullin-regulated phenotypes (10–13). Further, several components of the CSN have also been found to be directly associated with proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressors and can regulate their function (Table 2).

Table 2.

CSN5-Interacting Proteins Associated with Cancer

| CSN5-binding proteins | Stability of CN5-binding protein |

Known Cullin target? | Known to be polyubiquitin? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSN5 RNA1 or AS | CSN5 overexpression | |||

| p53 (86) | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | Yes |

| HIF-1α (32, 49) | Degraded | Stabilized | Yes | Yes |

| c-jun (58) | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | Yes |

| JunD (58) | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | Yes |

| SMAD4 (45) | Unknown | Degraded | Yes | Yes |

| SMAD7 (44) | Stabilized | Degraded | Unknown | Yes |

| ID1 (88) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Yes |

| ID3 (88) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Yes |

| Estrogen receptor α (106) | Unknown | Degraded | Unknown | Yes |

| Progesterone receptor (90) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Yes |

| SRC-1 (90) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Yes |

| Bcl-3 (109) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Yes |

| p27 (35) | Unknown | Degraded | Yes | Yes |

| αV Integrin (92) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| β2 Integrin (93) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| rLHR (94) | Unknown | Degraded | Unknown | Yes |

| Thioredoxin (95) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| DNA topoisomerase IIα (96) | Degraded | Stabilized | Unknown | Yes |

| IRE1 (97) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Yes |

| pVHL (32) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Yes |

| TRC8 (98) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| PGP9.5 (99) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| MIF (51) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

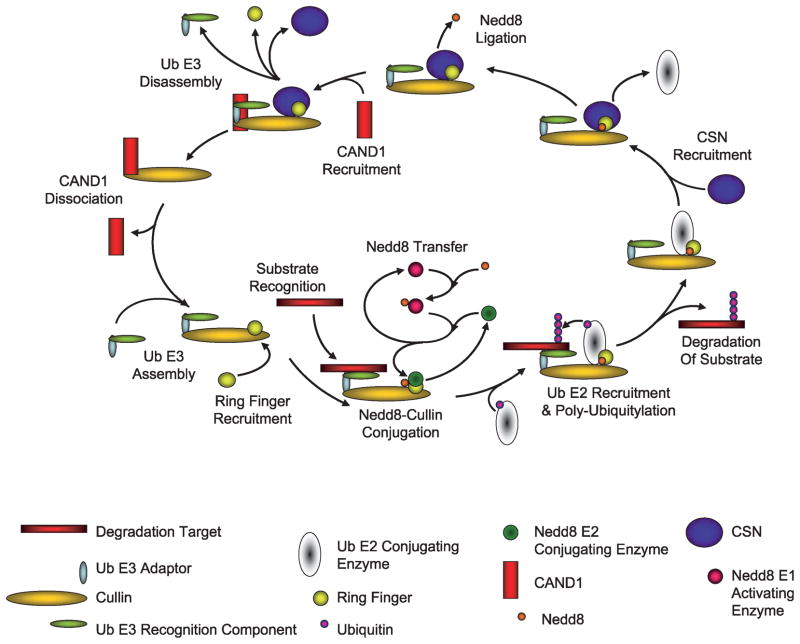

The most thoroughly studied function of the CSN is as a metalloproteinase capable of cleaving the protein Nedd8 covalently bound to the Cullin family of proteins (Fig. 1; refs. 10–12). This function has been proposed to be mediated by the catalytic subunit CSN5 but requires the assembly of the entire CSN holocomplex (10–12, 14–28). The deneddylation of Cullins is required for Cullin-mediated degradation of E3 substrates. Currently, it is thought that neddylation stimulates the assembly of competent E3-substrate complexes with their cognate E2 enzymes and that deneddylation facilitates the turnover of these complexes while maintaining E3 stability, thus recycling the E3s for further rounds of ubiquitylating activity (Figs. 1 and 2; refs. 10–12, 29, 30).

FIGURE 2.

Regulation of Cul-E3s by the CSN.

Function of CSN Subcomplexes

One of earliest observations of the CSN was that various CSN-subunit-containing complexes migrate differentially during native size fractionation chromatography or electrophoresis (31). Commonly, there is a 550- to 450-kDa band corresponding to the CSN holocomplex, but invariably there are multiple smaller complexes containing some but not all CSN subunits. There are also several supercomplexes thought to contain assembled CSN-Cul-E3 complexes and perhaps other 26S-associated proteins. The smaller complexes are of particular interest, as recent evidence has associated these complexes with deregulated function and oncogenic transformation (32, 33).

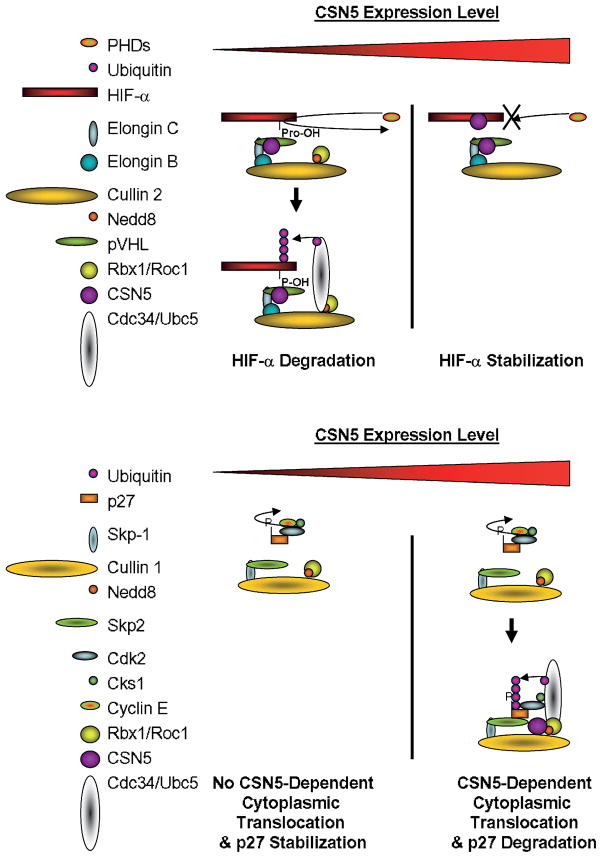

CSN5 is a common component of many of the small CSN complexes and can also exist in a monomeric form (reviewed by ref. 34). CSN5 proteolytic activity is required for the CSN-directed deneddylating of the Cullins. Its overexpression, which seems to be common in a variety of tumors (Table 3), has been noted to increase the small CSN5 complexes without affecting CSN5 association with the CSN holocomplex. Other CSN subunits also form smaller complexes as well, but the function of these subcomplexes remains virtually unstudied. Importantly, CSN5 is found in both the cytosol and the nucleus of mammalian cells, whereas the CSN holocomplex has been reported to be predominantly perinuclear/nuclear and perhaps associated with the nucleolus. One of the key studies suggesting that CSN5-containing small complexes might regulate oncogenic processes was the observation that CSN5 sequestered the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 in the cytosol, preventing nuclear accumulation and cell cycle arrest (Fig. 3; ref. 35). CSN5 overexpression can also lead to the deregulation of a variety of oncogenic processes leading to the hypothesis that CSN5 can constrain the degradation of target proteins in cells when its expression level, or perhaps undetermined forms of regulation, permit it to form non-CSN-associated holocomplexes. How CSN5 can interact with such a large number of proteins is currently undetermined. There seems to be no common domains within these proteins, suggesting that perhaps a common post-translational modification may occur or that a common structural feature is present that is not easily deduced by comparing secondary structure. One other possibility could be a redox-induced protein modification or stimulation of the unfolded protein response, as many of the proteins that interact with CSN5 are redox-responsive proteins.

Table 3.

CSN5 Overexpression Correlating Tumor Progression or Clinical Outcome

| Prognostic indicator | Cancer (reference) | Increased expression associated with poor clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|

| CSN5 | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (101) | Not evaluated |

| CSN5 | Hepatocellular carcinoma (53) | Gene amplification (76%) |

| CSN5 | Hepatocellular carcinoma (102) | Not evaluated |

| CSN5 | Laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (87) | Indicator of disease-free and overall survival |

| CSN5 | Oral squamous cell carcinoma (103) | Indicator of lymph node metastasis and poor prognosis |

| CSN5 | Lung adenocarcinoma (104) | Indicator of disease state but not clinical outcome |

| CSN5 | Breast ductal carcinoma in situ (105) | Expression is higher in lesions with necrosis |

| CSN5 | Node-negative breast cancer (89) | Associated with tumor size but not disease-free survival |

| CSN5 | Invasive breast carcinoma (107) | Indicator of disease progression and relapse |

| CSN5 | Melanoma (108) | Not evaluated |

| CSN5 | Rhabdomyosarcoma (91) | Not evaluated |

| CSN5 | Pituitary carcinomas (110) | Not evaluated |

| CSN5 | Neuroblastoma (111) | Localization associated with tumor differentiation |

| CSN5 | B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (112) | Not evaluated |

| CSN5 | Malignant lymphoma (thyroid; ref. 113) | Predictor of tumor grade and proliferative index |

FIGURE 3.

Examples of how normal Cul-E3s can become deregulated by high CSN5 protein expression.

Paradoxically, both Ras and FOXO4 activation results in the down-regulation of CSN5 (36, 37). Whether these are feedback mechanisms that result in cellular attempts to regulate cell cycle or other CSN5-mediated processes is not known. Hypoxia also results in the CSN5 transcript inhibition, suggesting that CSN5 is an important modulator of environmental homeostasis (38).

Chromosome Instability, DNA Damage, and Repair

Multiple subunits in the CSN are implicated in the DNA damage sensitivity and repair (39, 40). Chromosome instability has been linked with the rapid degradation of the DNA damage–binding protein (DDB2) through the proteasome pathway. Following irradiation, DDB2 binds damaged DNA and thus facilitates nucleotide excision repair of DNA lesions (41). DDB2 degradation is regulated by Cul-E3s and is thus implicated as a target of the CSN. The CSN complex negatively regulates the ubiquitin ligase activity in DDB2 and CSA complexes, potentially compromising their stability. Importantly, this regulation by CSN was dependent on CSN5, with knockdown of CSN5 reducing its repair activity by ~50% (41). Thus, deregulated Cullin activation by aberrant CSN function could compromise DDB2 protein levels, thus contributing to DNA damage–induced mutagenesis.

Another factor potentially affected by CSN misregulation is Cdt1 (21, 42), a replication initiator protein, regulated by the CSN following irradiation damage. Cdt1 interacts with the origin recognition complex, facilitating loading of the replication helicases called minichromosome maintenance complex to chromatin. Assembly of the pre-replicative complex occurs during G1 phase of the cell cycle. Once initiation of DNA synthesis occurs, reinitiation is prevented until the next G1 phase. Therefore, regulation of Cdt1 is important for maintaining genomic integrity. Altered CSN function would potentially result in overexpressed Cdt1 levels and genomic instability. Further, elevated Cdt1 levels have been shown to correlate with increased DNA damage and re-replication leading to activation of ATM/ATR, Chk2 kinases, and p53. Activation of these cell cycle checkpoints would induce p21 and arrest re-replication. However, continued Cdt1 elevation would continue to promote cell cycle progression leading to further genomic instability.

Interestingly, CSN interaction with p53 has been shown to target this tumor suppressor for degradation, greatly affecting the ability of the cells to respond to DNA damage and proceed through cell cycle or signal for apoptosis. Therefore, Cullin inactivation, due to altered CSN function, would most likely compromise p53 function leading to altered cell cycle and apoptotic functions.

Cell Cycle

Several studies have implicated the CSN in the regulation of proteins critical for the regulation of cellular proliferation. In one example, p27KIP1 was shown by Tomoda et al. (35, 43) to interact with CSN5, promoting the degradation of p27. Overexpression of CSN5 as well as other CSN components also facilitated p27 nuclear export and degradation. Cullin recognition and regulation is another potential mechanism of altering cellular proliferation by the CSN. Inhibition of Cullin regulation, through either improper activation or cycling of the Nedd8 modification, can have a dramatic effect in response to cancer cell growth and progression. A few interesting associations that could become altered via altered CSN function are the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p27 (35, 43), p57 (18), and p21 (14) and their transcriptional regulators (i.e., SMAD4 and SMAD7; refs. 44–47) as well as several cyclins (cyclin D1, cyclin E, and cyclin B1; refs. 17, 20, 24, 28). Theoretically, inhibition of Cullin activity would promote accumulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, restoring control to cell cycle and inhibiting cell proliferation. At least for p27, this does not occur, as CSN5 overexpression mislocalizes p27 to the cytosol and facilitates its degradation (Fig. 3). This highlights a key point in studying the CSN in oncogenesis in that deregulation of the CSN particularly by subunit overexpression can have varied results depending on specific E3 ligase and substrate mechanisms on protein degratory regulation.

Microenvironment Homeostasis and Angiogenesis

Several factors that regulate microenvironmental homeostasis associate with the CSN and are specifically bound by CSN5, becoming either degraded or stabilized as a result. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), in particular, has been shown by several groups to interact directly with CSN5 (32, 49). Subsequent CSN5 binding to HIF-1α interferes with hydroxylation via the prolyl hydroxylases leading to stabilization in the cell (Fig. 3). Overexpression of this CSN component leads to enhanced stabilization, with knockdown resulting in normal regulation of HIF-1α and subsequent degradation (32). Interestingly, endogenous CSN5 is also constitutively bound to the recognition component of the ubiquitin E3 ligase, the pVHL tumor suppressor that regulates HIF-1α degradation. Because pVHL is postulated to control other undetermined regulators of oxygen homeostasis independently of HIF, CSN5 deregulation could also affect these processes.

Other potential factors regulated by altered CSN function include Notch1 and Notch4 (50) that maintain cell-cell interaction while also promoting cell growth and progression and serving as critical mediators of angiogenic processes. Notch regulation is primarily controlled by TrCP association and Cul1; therefore, misregulated Notch degradation could be altered by deregulated CSN function.

Finally, CSN5 also interacts with MIF (51, 52). Several studies have indicated increased MIF expression in precancerous, cancerous, and metastatic tumors with increased expression correlating with tumor aggressiveness and contributing to tumor neovascularization. Hypoxic and hypoglycemic stresses have also been shown to strongly induce MIF expression and are key indicators of initiation of angiogenesis and correlate with vascular endothelial growth factor expression. Interestingly, Kleemann et al. (51) described how the association between MIF and CSN5 allows MIF to enter the cell, where it then negatively regulates CSN5 function. Thus, in this case, MIF is a potential regulator of CSN function and not the reverse, suggesting that microenvironmental stresses could possess feedback mechanisms that potentially regulate CSN function and, by extension, facilitate adaptive growth.

Clinical Studies Relevant to CSN

Several studies that are summarized in Table 3 have correlatively associated either CSN5 overexpression or cytosolic CSN5 expression to disease progression or clinical outcome. CSN5 is located on human chromosome 8q, which is frequently amplified in a large variety of cancers. CSN5 amplification has been identified in one study in hepatocellular carcinomas, with knockdown of CSN5 resulting in impaired ability of these cells to proliferate (53). To date, no published reports on CSN subunit amplification or deregulation of expression other than those described for CSN5 have been reported.

Conclusion and Perspectives

Current genetic studies from model organisms and molecular biology of the CSN clearly support the role of this complex in many functions important for tumor initiation and progression. The exact nature of how the CSN affects such a multitude of oncogenic processes, however, is only just beginning to be understood. For example, a paradox is evident in multiple published works in which the CSN is critical for degradation, yet overexpression of certain subunits yields loss-of-function phenotypes. CSN5, in particular, seems to function as a dominant negative of CSN function either by interacting with ubiquitin E3 substrates or the ubiquitin E3 ligases independent of the CSN holocomplex. These promiscuous interactions are thought to sterically alter E3 recognition, facilitate target mislocation, or alter CSN holocomplex recognition preventing Cullin turnover. These observations are pertinent to clinical oncology, as many cancers exhibit CSN5 overexpression. Further, the misregulation of specific CSN subunits could have diverse effects on different Cul-E3s and their substrates leading to the stability of some proteins and the degradation of others. How this complex regulatory network is selected for and adapted during oncogenesis will be a challenge for future studies.

The fact that the targets of the CSN, the Cullin complexes and their E3 substrates, are frequently deregulated during tumorigenesis strongly suggests that the CSN itself might become deregulated during tumor progression. Initial studies in human cancers have largely supported this hypothesis, although much work remains to be done. Whether the CSN is a good therapeutic target remains controversial. Proponents argue that the pleiotropic functions that such inhibitors could affect in cancers are sufficient to pursue drug studies; opponents, however, suggest that inhibition could result in further genomic instability resulting in more aggressive cancers and might have large toxic effects on normal tissues (3, 54). Knockdown of CSN5 in murine xenografts does significantly affect tumor growth, however, suggesting that this therapeutic paradigm may be worth pursuing (55).

Acknowledgments

Grant support: Pfizer Pharmaceuticals and National Cancer Institute grant R01-CA102301.

References

- 1.Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. Function and regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willems AR, Schwab M, Tyers M. A hitchhiker’s guide to the cullin ubiquitin ligases: SCF and its kin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1695:133–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guardavaccaro D, Pagano M. Oncogenic aberrations of cullin-dependent ubiquitin ligases. Oncogene. 2004;23:2037–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen LC, Manjeshwar S, Lu Y, et al. The human homologue for the Caenorhabditis elegans cul-4 gene is amplified and overexpressed in primary breast cancers. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3677–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yasui K, Arii S, Zhao C, et al. TFDP1, CUL4A, and CDC16 identified as targets for amplification at 13q34 in hepatocellular carcinomas. Hepatology. 2002;35:1476–84. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei N, Chamovitz DA, Deng XW. Arabidopsis COP9 is a component of a novel signaling complex mediating light control of development. Cell. 1994;78:117–24. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90578-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chamovitz DA, Deng XW. The novel components of the Arabidopsis light signaling pathway may define a group of general developmental regulators shared by both animal and plant kingdoms. Cell. 1995;82:353–4. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei N, Tsuge T, Serino G, et al. The COP9 complex is conserved between plants and mammals and is related to the 26S proteasome regulatory complex. Curr Biol. 1998;8:919–22. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seeger M, Kraft R, Ferrell K, et al. A novel protein complex involved in signal transduction possessing similarities to 26S proteasome subunits. FASEB J. 1998;12:469–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mikus P, Zundel W. COPing with hypoxia. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:462–73. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwechheimer C. The COP9 signalosome (CSN): an evolutionary conserved proteolysis regulator in eukaryotic development. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1695:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei N, Deng XW. The COP9 signalosome. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:261–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.112449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wee S, Geyer RK, Toda T, Wolf DA. CSN facilitates Cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase function by counteracting autocatalytic adapter instability. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:387–91. doi: 10.1038/ncb1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bornstein G, Bloom J, Sitry-Shevah D, et al. Role of the SCFSkp2 ubiquitin ligase in the degradation of p21Cip1 in S phase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25752–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301774200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carrano AC, Eytan E, Hershko A, Pagano M. SKP2 is required for ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the CDK inhibitor p27. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:193–9. doi: 10.1038/12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charrasse S, Carena I, Brondani V, Klempnauer KH, Ferrari S. Degradation of B-Myb by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis: involvement of the Cdc34-SCF(p45Skp2) pathway. Oncogene. 2000;19:2986–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganiatsas S, Dow R, Thompson A, Schulman B, Germain D. A splice variant of Skp2 is retained in the cytoplasm and fails to direct cyclin D1 ubiquitination in the uterine cancer cell line SK-UT. Oncogene. 2001;20:3641–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamura T, Hara T, Kotoshiba S, et al. Degradation of p57Kip2 mediated by SCFSkp2-dependent ubiquitylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10231–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1831009100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SY, Herbst A, Tworkowski KA, Salghetti SE, Tansey WP. Skp2 regulates Myc protein stability and activity. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1177–88. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koepp DM, Schaefer LK, Ye X, et al. Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination of cyclin E by the SCFFbw7 ubiquitin ligase. Science. 2001;294:173–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1065203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Zhao Q, Liao R, Sun P, Wu X. The SCF(Skp2) ubiquitin ligase complex interacts with the human replication licensing factor Cdt1 and regulates Cdt1 degradation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30854–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300251200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marti A, Wirbelauer C, Scheffner M, Krek W. Interaction between ubiquitin-protein ligase SCFSKP2 and E2F-1 underlies the regulation of E2F-1 degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:14–9. doi: 10.1038/8984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendez J, Zou-Yang XH, Kim SY, et al. Human origin recognition complex large subunit is degraded by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis after initiation of DNA replication. Mol Cell. 2002;9:481–91. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00467-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakayama K, Nagahama H, Minamishima YA, et al. Targeted disruption of Skp2 results in accumulation of cyclin E and p27(Kip1), polyploidy and centrosome overduplication. EMBO J. 2000;19:2069–81. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.9.2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oh KJ, Kalinina A, Wang J, et al. The papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein is ubiquitinated by UbcH7 and Cullin 1- and Skp2-containing E3 ligase. J Virol. 2004;78:5338–46. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5338-5346.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tedesco D, Lukas J, Reed SI. The pRb-related protein p130 is regulated by phosphorylation-dependent proteolysis via the protein-ubiquitin ligase SCF(Skp2) Genes Dev. 2002;16:2946–57. doi: 10.1101/gad.1011202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von der Lehr N, Johansson S, Wu S, et al. The F-box protein Skp2 participates in c-Myc proteosomal degradation and acts as a cofactor for c-Myc-regulated transcription. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1189–200. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu ZK, Gervais JL, Zhang H. Human CUL-1 associates with the SKP1/SKP2 complex and regulates p21(CIP1/WAF1) and cyclin D proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11324–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holmberg C, Fleck O, Hansen HA, et al. Ddb1 controls genome stability and meiosis in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 2005;19:853–62. doi: 10.1101/gad.329905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu JT, Lin HC, Hu YC, Chien CT. Neddylation and deneddylation regulate Cul1 and Cul3 protein accumulation. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1014–20. doi: 10.1038/ncb1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwok SF, Solano R, Tsuge T, et al. Arabidopsis homologs of a c-Jun coactivator are present both in monomeric form and in the COP9 complex, and their abundance is differentially affected by the pleiotropic cop/det/fus mutations. Plant Cell. 1998;10:1779–90. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.11.1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bemis L, Chan DA, Finkielstein CV, et al. Distinct aerobic and hypoxic mechanisms of HIF-α regulation by CSN5. Genes Dev. 2004;18:739–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.1180104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang HY, Zhou BP, Hung MC, Lee MH. Oncogenic signals of HER-2/neu in regulating the stability of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:24735–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chamovitz DA, Segal D. JAB1/CSN5 and the COP9 signalosome. A complex situation. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:96–101. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomoda K, Kubota Y, Arata Y, et al. The cytoplasmic shuttling and subsequent degradation of p27Kip1 mediated by Jab1/CSN5 and the COP9 signalosome complex. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2302–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104431200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukumoto A, Tomoda K, Kubota M, Kato JY, Yoneda-Kato N. Small Jab1-containing subcomplex is regulated in an anchorage- and cell cycle-dependent manner, which is abrogated by ras transformation. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1047–54. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang H, Zhao R, Yang HY, Lee MH. Constitutively active FOXO4 inhibits Akt activity, regulates p27Kip1 stability, and suppresses HER2-mediated tumorigenicity. Oncogene. 2005;24:1924–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denko NC, Fontana LA, Hudson KM, et al. Investigating hypoxic tumor physiology through gene expression patterns. Oncogene. 2003;22:5907–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mundt KE, Liu C, Carr AM. Deletion mutants in COP9/signalosome subunits in fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe display distinct phenotypes. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:493–502. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-10-0521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oron E, Mannervik M, Rencus S, et al. COP9 signalosome subunits 4 and 5 regulate multiple pleiotropic pathways in Drosophila melanogaster. Development. 2002;129:4399–409. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wittschieben BB, Wood RD. DDB complexities. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003;2:1065–9. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(03)00113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saxena S, Dutta A. Geminin-Cdt1 balance is critical for genetic stability. Mutat Res. 2005;569:111–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tomoda K, Kubota Y, Kato J. Degradation of the cyclin-dependent-kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 is instigated by Jab1. Nature. 1999;398:160–5. doi: 10.1038/18230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim BC, Lee HJ, Park SH, et al. Jab1/CSN5, a component of the COP9 signalosome, regulates transforming growth factor β signaling by binding to Smad7 and promoting its degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2251–62. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.6.2251-2262.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wan M, Cao X, Wu Y, et al. Jab1 antagonizes TGF-β signaling by inducing Smad4 degradation. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:171–6. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wan M, Huang J, Jhala NC, et al. SCF(β-TrCP1) controls Smad4 protein stability in pancreatic cancer cells. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1379–92. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62356-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wan M, Tang Y, Tytler EM, et al. Smad4 protein stability is regulated by ubiquitin ligase SCF β-TrCP1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14484–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bassermann F, von Klitzing C, Munch S, et al. NIPA defines an SCF-type mammalian E3 ligase that regulates mitotic entry. Cell. 2005;122:45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bae MK, Ahn MY, Jeong JW, et al. Jab1 interacts directly with HIF-1α and regulates its stability. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100442200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu G, Lyapina S, Das I, et al. SEL-10 is an inhibitor of notch signaling that targets notch for ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7403–15. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7403-7415.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kleemann R, Hausser A, Geiger G, et al. Intracellular action of the cytokine MIF to modulate AP-1 activity and the cell cycle through Jab1. Nature. 2000;408:211–6. doi: 10.1038/35041591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mitchell RA. Mechanisms and effectors of MIF-dependent promotion of tumourigenesis. Cell Signal. 2004;16:13–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patil MA, Gutgemann I, Zhang J, et al. Array-based comparative genomic hybridization reveals recurrent chromosomal aberrations and Jab1 as a potential target for 8q gain in hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:2050–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nalepa G, Wade Harper J. Therapeutic anti-cancer targets upstream of the proteasome. Cancer Treat Rev. 2003;29 (Suppl 1):49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(03)00083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Supriatno, Harada K, Yoshida H, Sato M. Basic investigation on the development of molecular targeting therapy against cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 in head and neck cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2005;27:627–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wei W, Jin J, Schlisio S, Harper JW, Kaelin WG., Jr The v-Jun point mutation allows c-Jun to escape GSK3-dependent recognition and destruction by the Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Welcker M, Orian A, Grim JA, Eisenman RN, Clurman BE. A nucleolar isoform of the Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase regulates c-Myc and cell size. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1852–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Claret FX, Hibi M, Dhut S, Toda T, Karin M. A new group of conserved coactivators that increase the specificity of AP-1 transcription factors. Nature. 1996;383:453–7. doi: 10.1038/383453a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Welcker M, Orian A, Jin J, et al. The Fbw7 tumor suppressor regulates glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylation-dependent c-Myc protein degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9085–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402770101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yada M, Hatakeyama S, Kamura T, et al. Phosphorylation-dependent degradation of c-Myc is mediated by the F-box protein Fbw7. EMBO J. 2004;23:2116–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Busino L, Donzelli M, Chiesa M, et al. Degradation of Cdc25A by β-TrCP during S phase and in response to DNA damage. Nature. 2003;426:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature02082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fong A, Sun SC. Genetic evidence for the essential role of β-transducin repeat-containing protein in the inducible processing of NF-κB2/p100. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22111–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200151200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fukuchi M, Imamura T, Chiba T, et al. Ligand-dependent degradation of Smad3 by a ubiquitin ligase complex of ROC1 and associated proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1431–43. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.5.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guardavaccaro D, Kudo Y, Boulaire J, et al. Control of meiotic and mitotic progression by the F box protein β-Trcp1 in vivo. Dev Cell. 2003;4:799–812. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lassot I, Segeral E, Berlioz-Torrent C, et al. ATF4 degradation relies on a phosphorylation-dependent interaction with the SCF(βTrCP) ubiquitin ligase. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2192–202. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.6.2192-2202.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maniatis T. A ubiquitin ligase complex essential for the NF-κB, Wnt/Wingless, and Hedgehog signaling pathways. Genes Dev. 1999;13:505–10. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.5.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mantovani F, Banks L. Regulation of the discs large tumor suppressor by a phosphorylation-dependent interaction with the β-TrCP ubiquitin ligase receptor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42477–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302799200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Margottin-Goguet F, Hsu JY, Loktev A, et al. Prophase destruction of Emi1 by the SCF(βTrCP/Slimb) ubiquitin ligase activates the anaphase promoting complex to allow progression beyond prometaphase. Dev Cell. 2003;4:813–26. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Orian A, Gonen H, Bercovich B, et al. SCF(β)(-TrCP) ubiquitin ligase-mediated processing of NF-κB p105 requires phosphorylation of its C-terminus by IκB kinase. EMBO J. 2000;19:2580–91. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Watanabe N, Arai H, Nishihara Y, et al. M-phase kinases induce phospho-dependent ubiquitination of somatic Wee1 by SCFβ-TrCP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4419–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brower CS, Sato S, Tomomori-Sato C, et al. Mammalian mediator subunit mMED8 is an Elongin BC-interacting protein that can assemble with Cul2 and Rbx1 to reconstitute a ubiquitin ligase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10353–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162424199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kuznetsova AV, Meller J, Schnell PO, et al. von Hippel-Lindau protein binds hyperphosphorylated large subunit of RNA polymerase II through a proline hydroxylation motif and targets it for ubiquitination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2706–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0436037100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang H, Ivan M, Min JH, Kim WY, Kaelin WG., Jr Analysis of von Hippel-Lindau hereditary cancer syndrome: implications of oxygen sensing. Methods Enzymol. 2004;381:320–35. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)81022-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kamizono S, Hanada T, Yasukawa H, et al. The SOCS box of SOCS-1 accelerates ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of TEL-JAK2. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12530–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010074200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rui L, Yuan M, Frantz D, Shoelson S, White MF. SOCS-1 and SOCS-3 block insulin signaling by ubiquitin-mediated degradation of IRS1 and IRS2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42394–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200444200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang DD, Lo SC, Cross JV, Templeton DJ, Hannink M. Keap1 is a redox-regulated substrate adaptor protein for a Cul3-dependent ubiquitin ligase complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:10941–53. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.24.10941-10953.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kurz T, Pintard L, Willis JH, et al. Cytoskeletal regulation by the Nedd8 ubiquitin-like protein modification pathway. Science. 2002;295:1294–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1067765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Geyer R, Wee S, Anderson S, Yates J, Wolf DA. BTB/POZ domain proteins are putative substrate adaptors for cullin 3 ubiquitin ligases. Mol Cell. 2003;12:783–90. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ou CY, Lin YF, Chen YJ, Chien CT. Distinct protein degradation mechanisms mediated by Cul1 and Cul3 controlling Ci stability in Drosophila eye development. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2403–14. doi: 10.1101/gad.1011402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wilkins A, Ping Q, Carpenter CL. RhoBTB2 is a substrate of the mammalian Cul3 ubiquitin ligase complex. Genes Dev. 2004;18:856–61. doi: 10.1101/gad.1177904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen X, Zhang Y, Douglas L, Zhou P. UV-damaged DNA-binding proteins are targets of CUL-4A-mediated ubiquitination and degradation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48175–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106808200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nag A, Bondar T, Shiv S, Raychaudhuri P. The xeroderma pigmentosum group E gene product DDB2 is a specific target of cullin 4A in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6738–47. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.6738-6747.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhong W, Feng H, Santiago FE, Kipreos ET. CUL-4 ubiquitin ligase maintains genome stability by restraining DNA-replication licensing. Nature. 2003;423:885–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Heuze ML, Guibal FC, Banks CA, et al. ASB2 is an Elongin BC-interacting protein that can assemble with Cullin 5 and Rbx1 to reconstitute an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5468–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Querido E, Morrison MR, Chu-Pham-Dang H, et al. Identification of three functions of the adenovirus e4orf6 protein that mediate p53 degradation by the E4orf6-E1B55K complex. J Virol. 2001;75:699–709. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.2.699-709.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bech-Otschir D, Kraft R, Huang X, et al. COP9 signalosome-specific phosphorylation targets p53 to degradation by the ubiquitin system. EMBO J. 2001;20:1630–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dong Y, Sui L, Watanabe Y, et al. Prognostic significance of Jab1 expression in laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:259–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Berse M, Bounpheng M, Huang X, et al. Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of Id1 and Id3 is mediated by the COP9 signalosome. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:361–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Esteva FJ, Sahin AA, Rassidakis GZ, et al. Jun activation domain binding protein 1 expression is associated with low p27(Kip1) levels in node-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5652–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chauchereau A, Georgiakaki M, Perrin-Wolff M, Milgrom E, Loosfelt H. JAB1 interacts with both the progesterone receptor and SRC-1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8540–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tsuchida R, Miyauchi J, Shen L, et al. Expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27/Kip1 and AP-1 coactivator p38/Jab1 correlates with differentiation of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2002;93:1000–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2002.tb02476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Levinson H, Sil AK, Conwell JE, Hopper JE, Ehrlich HP. αV Integrin prolongs collagenase production through Jun activation binding protein 1. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;53:155–61. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000112281.97409.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bianchi E, Denti S, Granata A, et al. Integrin LFA-1 interacts with the transcriptional co-activator JAB1 to modulate AP-1 activity. Nature. 2000;404:617–21. doi: 10.1038/35007098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li S, Liu X, Ascoli M. p38JAB1 binds to the intracellular precursor of the lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor and promotes its degradation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13386–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hwang CY, Ryu YS, Chung MS, et al. Thioredoxin modulates activator protein 1 (AP-1) activity and p27Kip1 degradation through direct interaction with Jab1. Oncogene. 2004;23:8868–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yun J, Tomida A, Andoh T, Tsuruo T. Interaction between glucose-regulated destruction domain of DNA topoisomerase IIα and MPN domain of Jab1/CSN5. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31296–303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401411200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Oono K, Yoneda T, Manabe T, et al. JAB1 participates in unfolded protein responses by association and dissociation with IRE1. Neurochem Int. 2004;45:765–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gemmill RM, Bemis LT, Lee JP, et al. The TRC8 hereditary kidney cancer gene suppresses growth and functions with VHL in a common pathway. Oncogene. 2002;21:3507–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Caballero OL, Resto V, Patturajan M, et al. Interaction and colocalization of PGP9.5 with JAB1 and p27(Kip1) Oncogene. 2002;21:3003–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.De Sepulveda P, Ilangumaran S, Rottapel R. Suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 inhibits VAV function through protein degradation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14005–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.c000106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fukumoto A, Ikeda N, Sho M, et al. Prognostic significance of localized p27Kip1 and potential role of Jab1/CSN5 in pancreatic cancer. Oncol Rep. 2004;11:277–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Takami T, Terai S, Yokoyama Y, et al. Human homologue of maid is a useful marker protein in hepatocarcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1369–80. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shintani S, Li C, Mihara M, et al. Skp2 and Jab1 expression are associated with inverse expression of p27(KIP1) and poor prognosis in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Oncology. 2003;65:355–62. doi: 10.1159/000074649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Goto A, Niki T, Moriyama S, et al. Immunohistochemical study of Skp2 and Jab1, two key molecules in the degradation of p27, in lung adenocarcinoma. Pathol Int. 2004;54:675–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2004.01679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Emberley ED, Alowami S, Snell L, Murphy LC, Watson PH. S100A7 (psoriasin) expression is associated with aggressive features and alteration of Jab1 in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Breast Cancer Res. 2003;6:R308–15. doi: 10.1186/bcr791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Callige M, Kieffer I, Richard-Foy H. CSN5/Jab1 is involved in ligand-dependent degradation of estrogen receptor α by the proteasome. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4349–58. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4349-4358.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kouvaraki MA, Rassidakis GZ, Tian L, et al. Jun activation domain-binding protein 1 expression in breast cancer inversely correlates with the cell cycle inhibitor p27(Kip1) Cancer Res. 2003;63:2977–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ivan D, Diwan AH, Esteva FJ, Prieto VG. Expression of cell cycle inhibitor p27Kip1 and its inactivator Jab1 in melanocytic lesions. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:811–8. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dechend R, Hirano F, Lehmann K, et al. The Bcl-3 oncoprotein acts as a bridging factor between NF-κB/Rel and nuclear co-regulators. Oncogene. 1999;18:3316–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Korbonits M, Chahal HS, Kaltsas G, et al. Expression of phosphorylated p27(Kip1) protein and Jun activation domain-binding protein 1 in human pituitary tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2635–43. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.6.8517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Shen L, Tsuchida R, Miyauchi J, et al. Differentiation-associated expression and intracellular localization of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27KIP1 and c-Jun co-activator JAB1 in neuroblastoma. Int J Oncol. 2000;17:749–54. doi: 10.3892/ijo.17.4.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Qi CF, Xiang S, Shin MS, et al. Expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 and its deregulation in mouse B cell lymphomas. Leuk Res. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ito Y, Yoshida H, Matsuzuka F, et al. Jun activation domain-binding protein 1 expression in malignant lymphoma of the thyroid: its linkage to degree of malignancy and p27 expression. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:4121–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]