Abstract

Self-assembled rosette nanotubes (RNTs), obtained from a twin G∧C base functionalized with lysine-arginine-serine-arginine (KRSR–(G∧C)2), were designed and investigated as bioactive coatings on titanium. These results were compared to RNTs derived from Lysine G∧C (K G∧C), Arg-Gly-Asp G∧C (RGD G∧C) and aminobutane–(G∧C)2 (AB–(G∧C)2). The results from this study revealed that these materials had excellent cytocompatibility properties as they enhanced osteoblast (bone forming cell) adhesion when coated on titanium. In particular, KRSR and RGD functionalized RNTs coated on titanium promoted the greatest osteoblast densities relative to untreated titanium. Furthermore, KRSR functionalized RNTs selectively improved osteoblast adhesion relative to fibroblast (soft-tissue forming cell) and endothelial cell adhesion. In contrast with these results, RNTs obtained from an unfunctionalized twin base (AB–(G∧C)2), RGD G∧C co-assembled with K G∧C and K-G∧C significantly enhanced endothelial cell attachment, which may find applications in the vascularization of newly formed bone tissue. In summary, these studies suggest that the surface of orthopedic implant materials (such as titanium) could be tailored to promote selective cell adhesion using biologically-inspired nanotubular structures functionalized with osteogenic compounds.

Keywords: rosette nanotubes, nanomaterials, biomimetic, osteogenic peptides, coating, orthopedic implant

INTRODUCTION

Each year, millions of Americans endure intense pain caused by various bone diseases often resulting in costly orthopedic implant surgeries. Specifically, for hip and knee replacements, surgical procedures drastically increased from 258,000 and 299,000 in 2000, respectively, to 482,000 and 542,000 replacements in 2006, respectively [1]. However, due to frequently reported complications (such as inflammation and implant loosening), revision surgeries are required, which add to patient pain as well as health insurance costs. A significant paradigm shift in this field is the design of biologically-inspired coatings that can turn conventional inert metal implant surfaces (such as titanium) into biomimetic nanostructured surfaces that enhance cell adhesion and osseointegration [2].

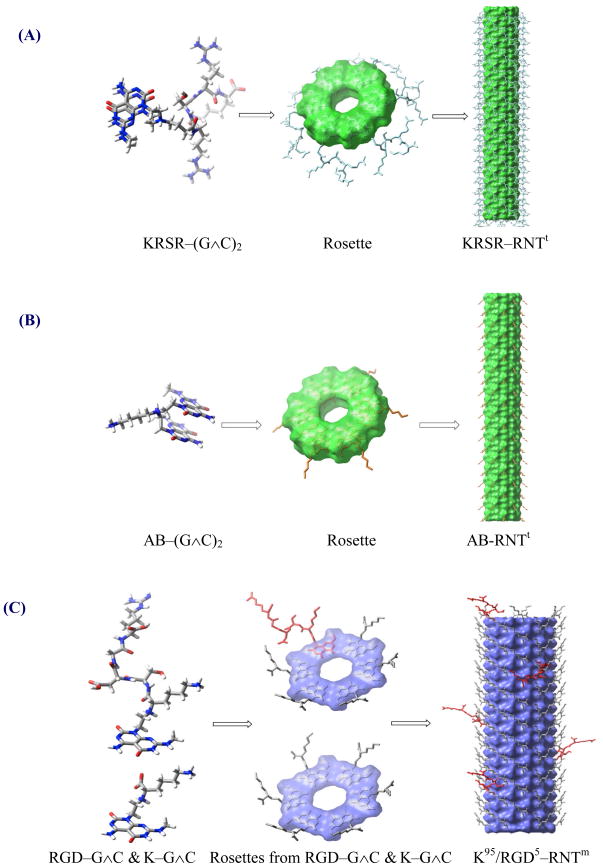

For this purpose, we investigated rosette nanotubes (RNTs) not only as a biomimetic nanostructured material but also as a delivery system for osteogenic peptides. The RNTs are obtained through the self-assembly of low molecular weight synthetic DNA base analogues (G∧C) in aqueous solutions. The G∧C moiety [3] undergoes a self-assembly process, fueled by an array of hydrogen bonds, to produce a six-membered supermacrocycle (rosette). Stacking of these rosettes gives rise to a nanotube with a very high aspect ratio. While in the case of the mono base (e.g. K–G∧C), the rosette is maintained by 18 H-bonds, for the twin base (e.g. KRSR–(G∧C)2), the hexameric twin rosette is held by 36 H-bons (Figure 1) [4]. As such, the resulting RNTs are more stable due to increased H-bonding interactions and reduced steric repulsion and charge density as opposed to RNTs from the mono base system. Unlike carbon nanotubes, the RNTs possess the advantages of being water soluble, less toxic, metal-free, and readily obtained in analytically pure form [3–9].

Figure 1.

Self-assembly of rosette nanotubes from twin and single DNA bases. The models shown are not drawn to scale. (A) Self-assembly of six KRSR–(G∧C)2 twin modules to give a twin rosette, which then stack to give the KRSR RNTt nanotube. (B) Self-assembly of six AB–(G ∧C)2 twin modules to give a twin rosette, which then stack to give the AB-RNTt nanotube. (C) Co-assembly of K–G∧C and RGD–G∧C modules to give a rosette, which then stack to give the K95/RGD5–RNTm nanotube. (D) Self-assembly of six K–G∧C modules to give a rosette, which then stack to give the K–RNTm nanotube.

Previous studies have highlighted the exceptional cytocompatibility properties of RNTs assembled from single G∧C motifs for various tissue engineering applications [5–9]. For example, a composite of these RNTs and nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite in poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) hydrogels enhanced osteoblast adhesion more than two times compared to hydrogel controls [8]. Journeay et al. have also demonstrated that the same RNTs have low acute toxicity in vivo [10]. In summary, RNTs are a promising nano-biomaterial for orthopedic applications because they are biocompatible, architecturally and nano-structurally similar to the extra-cellular matrix of bone [6–8]; they offer a versatile surface chemistry to tailor cell adhesion and subsequent functions [7]; and are an excellent calcification template [8].

Since greater osteoblast activity is crucial at the bone-implant interface where numerous cells are activated after implantation, an implant surface that selectively promotes osteoblast adhesion over other cells holds great potential for orthopedic implants. Osteoblast adhesion on implants can be mediated by the use of various amino acids or peptide sequences (such as RGD), which activate osteoblast membrane integrin receptors. Osteoblast adhesion may also be regulated via cell-membrane heparin sulphate proteoglycans and heparin-binding sites on proteins (i.e., fibronectin and collagen) [11–17]. For example, Dee and co-workers demonstrated for the first time that KRSR peptides immobilized on glass selectively enhanced osteoblast adhesion via heparin sulphate proteoglycan mediated mechanisms, but not endothelial cells or fibroblasts [17]. The latter, in particular, are undesirable cells for orthopedic applications because of their tendency to synthesize fibrous soft tissue around implants.

While these earlier reports highlight the separate capabilities of RNTs, RGD, and KRSR, the present study addresses the question as to whether osteoblast, fibroblast and endothelial cell adhesion on Ti can be controlled using a combination of the above to create specific osteogenic RNTs. To this end, we investigated the effect of RNTs derived from twin G∧C base [4, 18] functionalized with the osteogenic peptide KRSR (KRSR–(G∧C)2) on cell adhesion and compared them to other RNTs derived from lysine functionalized mono G∧C base (K–G∧C), RGD–G∧C co-assembled with K–G∧C [6, 7], and unfunctionalized aminobutane (AB) twin G∧C (AB–(G∧C)2) (Figure 1).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Synthesis of twin G∧C bases

All the reagents and solvents used in the synthesis of RNTs, were obtained from Aldrich, Novabiochem, BaChem, Fluka, Fisher Scientific or Advanced ChemTech, and were used without further purification. Reagent grade dichloromethane (CH2Cl2), methanol (MeOH) and ether (Et2O) were purified on an MBraun solvent purification system. The KRSR–(G∧C)2 and AB–(G∧C)2 modules were synthesized according to the procedures illustrated in Figure 2.

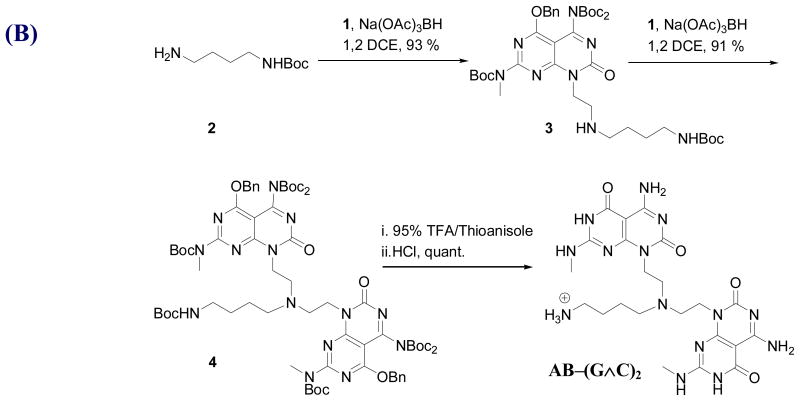

Figure 2.

A synthetic scheme of (A) Wang resin protected KRSR peptide coupling onto the twin G∧C bases (KRSR–(G∧C)2) and (B) AB–(G∧C)2 twin modules.

Standard Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis was used to prepare the Wang resin-supported KRSR peptide. To anchor the first amino acid to the resin, Fmoc-amino acid (4 eq) and p-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) (1 eq) in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 8 mL) were poured into a disposable plastic syringe containing the Wang resin (1 eq). After activating the resin for 20 min, N, N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC, 4 eq) was added to the vessel and the reaction mixture was shaken for 6 h. The resin was then filtered under a vacuum, washed with 10 mL each of CH2Cl2, MeOH, DMF and then treated with 50:50 acetic anhydride/pyridine (5 mL, 1 × 10 min and 2 × 20 min) to cap the unreactive hydroxyl groups. The resin was then filtered and washed with (3 × 10 mL) DMF, CH2Cl2 and MeOH and dried under vacuum. The substitution degree (0.52 mmol/g) was determined by spectroscopic quantification of the fulvene-piperidine adduct at 301 nm on a resin sample.

Subsequent amino acids were coupled as follows: the Fmoc protecting group was removed by incubation of the resin in 20% piperidine/DMF (5 mL, 1 × 5 min, 1 × 30 min). The resulting peptidyl resin was washed with 10 mL each of CH2Cl2, MeOH, and DMF. N-ethyl-N-isopropylpropan-2-amine (DIEA, 8 eq) was added to the mixture of amino acid (4 eq relative to resin loading) and 2-(1H-Benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU, 4 eq) in DMF solution, and the mixture was activated by shaking for 3 min. The resulting mixture was then added to the peptidyl resin and was shaken for 3 h. The peptidyl resin was then drained and washed with 10 mL each of CH2Cl2, MeOH and DMF. The absence of free amino groups was confirmed with the Kaiser test [19]. The Fmoc protecting group was removed by incubation of the resin in 20% piperidine/DMF (5 mL, 1 × 5 min, 1 × 30 min). The resulting peptidyl resin was washed with 10 mL each of CH2Cl2, MeOH, and DMF.

To prepare KRSR–(G∧C)2, the Wang resin-supported KRSR peptide was coupled to the G∧C aldehyde 1 (Figure 2A). The G∧C aldehyde 1 (4 eq relative to resin loading) was added to the peptidyl resin in 1,2-dichloroethane (1,2-DCE, 5 mL), and the mixture was shaken for 4 h. NaBH(OAc)3 (2 eq) and DIEA (4 eq) were then added and the mixture was shaken for 36 h, after which another 2 eq NaBH(OAc)3 and 4 eq of DIEA were added and shaken for an additional 36 h. The resin was drained and the resulting peptidyl-resin was washed with CH2Cl2, MeOH and DMF (4 × 10 mL each), and dried under vacuum. Cleavage from the resin and deprotection was achieved by treating the resin with 95% TFA/water for 2 h. The beads were filtered over celite and the resulting filtrate was concentrated to a viscous liquid (rotavap). Cold Et2O was then added to precipitate crude KRSR–(G∧C)2, which was isolated by centrifugation. The supernatant liquid was removed by decantation. The residual solid was resuspended in Et2O (2 × 15 mL), sonicated, and centrifuged. The precipitate was dried to yield the desired KRSR–(G∧C)2 as an off-white powder.

To prepare AB–(G∧C)2, commercially available amine 2 (1.00 g, 1.57 mmol) was added to a solution of G∧C aldehyde 1 (0.148 g, 0.784 mmol) in 1, 2 DCE (10 mL) at room temperature under N2 and stirred for 30 min. NaBH(OAc)3 (0.395 g, 1.88 mmol) was added and the resulting mixture was stirred for an additional 15 h. The reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (50 mL) and then washed with water (10 mL), brine (15 mL), dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated (rotavap). Compound 3 (1.36 g, 93%) was obtained as a white foam after silica gel flash chromatography (0–10% MeOH/EtOAc). G∧C aldehyde 1 (0.100 g, 0.155 mmol) was then added to a solution of monomer 3 (0.126 g, 0.155 mmol) in 1,2 DCE (10 mL) at room temperature under N2 and stirred for 30 min. NaBH(OAc)3 (0.039 g, 0.186 mmol) was added and the resulting mixture was stirred for an additional 15 h. The reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (50 mL) and washed with water (10 mL), brine (15 mL), dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. Compound 4 (0.204 g, 91%) was obtained as a white foam after silica gel flash chromatography (0–50% EtOAc/Hexanes). Compound 4 (0.106 g, 0.074 mmol) was stirred in 95% TFA/thioanisole (10 mL) for 72 h. Et2O (60 mL) was then added to the reaction mixture and the precipitate formed, was centrifuged. The residual solid was resuspended in Et2O, sonicated and centrifuged. This process was repeated until no UV-active product could bedetected in the Et2O wash (by spotting on a silica plate). The resulting TFA salt of AB–(G∧C)2 was dried and then dissolved in 1M hydrochloric acid (10 mL), followed by removal of the solvent under reduced pressure. This process was repeated twice before the solid was dried under vacuum for 72 h to give the HCl salt of AB–(G∧C)2 as an off-white powder in quantitative yield.

Self-assembly of RNTs in water

Stock solutions (1 mg/mL) of RNTs assembled from functionalized twin bases AB–(G∧C)2 and KRSR–(G∧C)2 (referred to as AB RNTt and KRSR–RNTt, respectively) were prepared by dissolving the corresponding motifs (AB–(G∧C)2 isolated either as a TFA or HCl salt) in deionized water (dH2O). The stock solutions were then diluted to 0.1 mg/mL and 0.01 mg/mL solutions for comparison purposes as required for this study. RGD–G∧C and K–G∧C were prepared as previously reported [3, 7]. K–RNTm refer to RNTs assembled from functionalized mono base K–G∧C. K99/RGD1–RNTm and K95/RGD5–RNTm refer to RNTs co-assembled from mono bases K–G∧C and RGD–G∧C in a molar ratio of 99% and 95%, respectively [7]. All the RNT solutions were filtered through a 0.22 μm syringe filter.

Characterization of KRSR–(G∧C)2 and AB–(G∧C)2

KRSR–(G∧C)2, AB–(G∧C)2 and all intermediate molecules were characterized by 1H/13C NMR spectroscopy, high resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HR EI-MS), and elemental analysis. 1H/13C NMR spectra were recorded with the solvent as an internal reference on Varian Inova NMR spectrometers (500 or 600 MHz) at the National Institute for Nanotechnology or Department of Chemistry, University of Alberta. The NMR data are presented as follows: chemical shift, peak assignment, multiplicity, coupling constant, and integration. The mass spectra were obtained from the Mass Spectrometry Laboratory at the Department of Chemistry, University of Alberta. These data are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

1H NMR, 13C NMR, HR EI-MS and elemental analysis data of KRSR–(G∧C)2

| KRSR–(G∧C)2 Characterization Data | |

|---|---|

| 1H NMR (DMSO; 600 MHz) | 12.34 (bs, 2H), 9.24 (bs, 2H), 9.06 (bs, 2H), 8.97 (m, 1H), 8.26 (m, 2H), 8.13 (m, 2H), 8.08–7.98 (m, 2H), 7.65 (bs, 3H), 7.54–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.39–7.16 (bs, 4H), 7.10–6.65 (bs, 4H), 4.43 (m, 4H), 4.35–4.27 (m, 3H), 4.12 (m, 1H), 3.62 (m, 1H), 3.59–3.47 (m, 4H), 3.33 (m, 1H), 3.08 (bs, 5H), 2.91 (d, 6H, J = 4.2 Hz), 2.74 (m, 4H), 2.34–2.23 (m, 2H), 1.90–1.86 (m, 2H), 1.77–1.64 (m, 2H), 1.60–1.43 (m, 8H), 1.34–1.27 (m, 2H) |

| 13C NMR (DMSO; 150 MHz) | 174.9, 174.1, 173.7, 172.0, 171.9, 170.4, 169.8, 162.6, 161.7, 160.3, 157.2, 156.7, 156.0, 148.6, 128.9, 128.7, 83.0, 82.2, 62.2, 55.4, 52.6, 52.5, 52.2, 52.0, 49.5, 40.9, 39.2, 39.1, 31.0, 30.7, 29.8, 29.5, 28.3, 27.1, 27.0, 25.4, 25.3, 22.9 |

| HR EI-MS | Calculated mass for C43H71N24O11 [M+H]+ 1099.5729; found 1099.5727 |

| Elemental analysis | Calculated for (C43H70N24O11)(TFA)5(H2O)3(H2SO4)1.5(Et2O) = C (35.22), H (4.82), N (17.30), S (2.47); found: C (35.20), H (4.71), N (17.25), S (2.49) |

Table 2.

1H NMR, 13C NMR, HR EI-MS and elemental analysis data of AB (G∧C)2 and intermediates

| AB–(G∧C)2 and intermediate Characterization Data | |

|---|---|

| Compound 3 | Rf = 0.25 (10% MeOH in EtOAc); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) (ppm) 7.44–7.32 (m, 5H), 5.56 (s, 2H), 4.75 (bs, 1H), 4.50 (t, 2H, J = 6.3 Hz), 3.46 (s, 3H), 3.07 (app. t, 4H, J = 6.0 Hz), 2.73 (t, 2H, J = 6.9 Hz), 1.58 (s, 9H), 1.54–1.44 (m, 4H), 1.42 (s, 9H), 1.33 (s, 18H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125, MHz) (ppm) 165.8, 161.2, 160.9, 160.5, 156.0, 155.9, 152.6, 149.3, 134.9, 128.6, 128.5, 128.3, 93.1, 83.8, 83.3, 70.1, 50.0, 47.0, 42.6, 40.2, 34.9, 28.4, 28.1, 27.8, 27.6, 26.3; HR EI-MS + calculated for C40H61N8O10 [M]+ 813.4505, found 813.4507. |

| Compound 4 | Rf = 0.26 (50% EtOAc in hexanes); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) (ppm) 7.46–.33 (m, 10H), 5.57 (s, 4H), 4.87 (bs, 1H), 4.39 (t, 4H, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.48 (s, 6H), 3.06 (m, 2H), 2.90 (t, 4H, J = 7.3 Hz), 2.67 (m, 2H), 1.56 (s, 18H), 1.41 (s, 14H), 1.31 (s, 36H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) (ppm) 165.7, 161.2, 161.1, 160.3, 156.1, 155.6, 152.6, 149.3, 135.0, 128.6, 128.5, 127.8, 114.0, 92.9, 83.7, 82.9, 78.8, 70.1, 53.9, 50.9, 41.3, 40.5, 35.0, 29.7, 28.5, 28.1, 27.9, 25.1; HR EI-MS + calculated for C71H100N14O18Na[M+Na] 1459.72377, found 1459.72376. |

| AB–(G∧C)2 | mp = 296–301 °C (Decomposition); 1H NMR (DMSO, 600 MHz) (ppm) 12.32 (s, 2H), 9.15 (s, 2H), 8.90 (s, 2H), 8.57 (app. q, 2 H, J = 4.8 Hz), 8.11 (bs, 3H), 4.45 (bs, 2H), 3.46 (bs, 3H), 3.30 (bs, 4H), 2.95 (d, 6H, J = 4.7 Hz), 2.81–2.75 (m, 2H), 1.85–1.75 (m, 2H), 1.70–1.58 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO, 100 MHz) (ppm) 160.3, 159.6, 155.9, 155.6, 147.6, 82.4, 51.2, 48.3, 37.8, 36.0, 27.7, 23.8, 19.7; HR EI-MS calculated for C22H33N14O4 [M+H]+ 557.2804, found 557.2803; Elemental analysis calculated for C22H32N14O4(HCl)4(H2O)1.5 C, 36.22, H, 5.39, N, 26.88, found C, 36.31, H, 5.35, N, 26.44. |

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging

TEM was used to characterize the various single and twin base RNT morphologies. As previously described [20], carbon-coated 400-mesh copper grids (EM Sciences, PA) were floated on a dH2O droplet of each RNT (0.1 mg/mL or 0.01 mg/mL) for 2 min to adsorb the RNTs. The grids were then placed onto a droplet of dH2O for 20 s to remove excess non-adherent RNTs before they were placed on a second droplet of 2% aqueous uranyl acetate for 20 s to negatively stain the RNTs. The grids were then dried with filter paper and imaged on a Philips EM410 under an acceleration voltage of 120 kV. The KRSR peptide (not coupled to G∧C base) was also imaged as a control experiment.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging and atomic force microscopy (AFM) imaging

For SEM imaging, twin bases (0.5 mg/mL) were dissolved in dH2O by sonication at room temperature for ~2 min. The solutions were filtered on 0.25 μm Whatmann filter membranes, heated to boiling (to promote self-assembly), and aged for 1 day. The solutions were diluted to 0.025 mg/mL with dH2O prior to imaging. SEM samples were prepared by floating a carbon-coated 400-mesh copper grid on a droplet of the diluted RNT solution for 10 s. The grid was blotted and floated onto a drop of 2% uranyl acetate for 10 s. The RNT-coated grid was then air-dried and heated on a hot-plate (100 °C) for 15 min before imaging on a high resolution Hitachi S-4800 SEM.

For AFM imaging, one drop of the diluted RNT solution (0.05 mg/mL) was deposited onto a freshly cleaved mica substrate (1 cm2) for 10 s and excess solution was blotted using filter paper. The sample surface was imaged using a Digital Instruments/Veeco Instruments MultiMode Nanoscope IV AFM equipped with an E scanner in tapping mode. Silicon cantilevers (MikroMasch USA, Inc.) with low spring constants of 4.5 N/m, a scan rate of 0.5-1 Hz and amplitude setpoint of 1 V were used.

Cytocompatibility assays of RNT coatings on Ti

Preparation of RNT coatings on Ti

Titanium (1 cm × 1 cm × 0.05 cm) (Alfa Aesar Ti foil) and glass coverslips were soaked in acetone for 15 min, sonicated for 15 min in acetone, and rinsed with dH2O. They were then soaked and sonicated in 70% ethanol and rinsed with dH2O. Lastly, they were soaked and sonicated in dH2O for another 15 min and rinsed. The glass was then etched in 1 M NaOH for 1 h and thoroughly rinsed in dH2O. All of the Ti and glass coverslips were oven-dried overnight and autoclaved for sterilization. The day before cell seeding, the cleaned Ti substrates were coated with the various RNTs (0.01 mg/mL) and KRSR peptide (0.01 mg/mL) solutions for 45 min at room temperature. They were then removed from the solutions and air-dried overnight.

Osteoblast, fibroblast and endothelial cell culture

A human fetal osteoblast cell line (ATCC, CRL-11372, VA) was cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM, Invitrogen Corporation) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone, UT) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S, Hyclone, UT) under standard cell culture conditions (37°C, humidified, 5% CO2 in air). Cells were used up to passage numbers of 8–11 in the experiments without further characterization.

A rat skin fibroblast cell line (FR, ATCC, CRL-1213) was cultured in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM, ATCC, 30–2003) supplemented with 10% FBS under standard cell culture conditions. Rat aortic endothelial cells (RAEC, VEC Technologies) were cultured in MCDB-131 complete medium (VEC Technologies) under standard cell culture conditions. The fibroblasts were used at passage numbers 6–9 and the endothelial cells were used at passage numbers 6–11 during culture. The cell medium was replaced every other day.

Osteoblast, fibroblast and endothelial cell adhesion

Osteoblasts, fibroblasts and endothelial cells were seeded onto the substrates at a density of 3500 cells/cm2 in 24-well cell culture plates and were incubated in 1 mL cell culture medium (specifically, DMEM supplemented with FBS and P/S for osteoblasts, EMEM supplemented with FBS for fibroblasts and MCDB-131 complete medium for endothelial cells) for 4 h. Then, the substrates were rinsed three times with a phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to remove non-adherent cells. The remaining cells were fixed using 10% normal buffered formaldehyde (Fisher Scientific) for 10 min and 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) for 5 min. Cells were then stained with rhodamine-phalloidin (staining F-actin filaments, Molecular Probes) to examine cell spreading and were further stained with DAPI (Invitrogen). The cells were observed using a fluorescent microscope (Axiovert 200M, Zeiss) and five different areas of each sample were imaged. The cell density was then determined by counting cells using Image Pro Analyzer. All cellular experiments were run in triplicate and repeated three times for each substrate.

Statistics

Data are presented as the mean value ± the standard error of the mean and were analyzed with a student’s t-test to make pair-wise comparisons. Statistical significance was considered at p<0.1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis

Two new self-assembling modules KRSR–(G∧C)2 and AB–(G∧C)2 were synthesized according to the synthetic schemes in Figures 2A and 2B, respectively. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the NMR and MS data of KRSR–(G∧C)2 and AB–(G∧C)2 compounds. Standard Fmoc [21, 22] solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) was used to prepare KRSR–(G∧C)2. SPPS [23] is a simple procedure, which allows rapid synthesis of peptides in good yields. This method eliminates solubility, purification and racemization issues, common with solution phase peptide synthesis. The carboxyl groups of the protected amino acid Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-OH was first coupled to the hydroxyl groups on the Wang resin. The Fmoc group of the lysine anchored to the resin was removed under basic conditions, after which it was reacted with the second amino acid Fmoc-Arg(PBf)-OH. The same procedure was repeated for subsequent amino acid couplings with Fmoc-Ser(tBu)-OH, Fmoc-Arg(PBf)-OH and Fmoc-γ-Abu-OH. The terminal Fmoc group on the Wang resin-supported peptide was removed and the resulting free amine was reductively coupled to G∧C aldehyde. The desired motif KRSR–(G∧C)2 was obtained upon deprotection and cleavage from the resin under strongly acidic conditions.

The synthetic scheme (Figure 2B) was carried out for preparation of module AB–(G∧C)2 from the G∧C aldehyde and t-butyl 4-aminobutylcarbamate via two consecutive reductive amination reactions followed by removal all protecting groups.

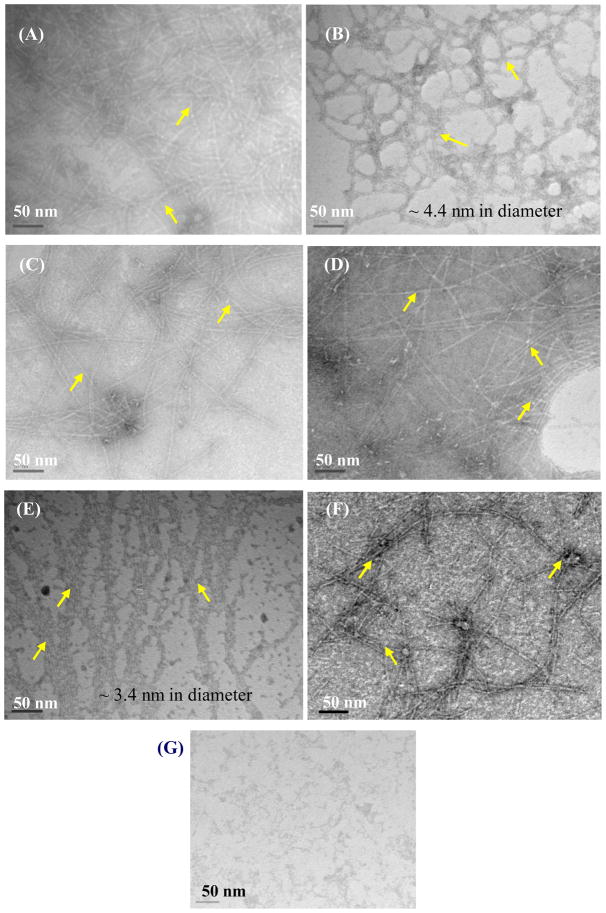

Microscopy studies

Irrespective of the side chains on the G∧C motif, all the resulting RNTs showed nanostructures with high aspect ratios (Figure 3). TEM images revealed a larger diameter (4.4 ± 0.2 nm) for KRSR–RNTt (Figures 3A–B) as compared to AB–RNTt (3.5 ± 0.2 nm) (Figure 3C–D) due to the bulkier KRSR moiety attached on the periphery of the twin base. K–RNTm and K95/RGD5–RNTm (Figure 3E–F) featured a diameter of 3.4 ± 0.3 nm. As expected, the control sample with KRSR peptides only did not show similar morphologies to the RNT molecules (Figure 3G).

Figure 3.

TEM images of RNTs investigated: (A) and (B) 0.1 mg/mL and 0.01 mg/mL KRSR–RNTt; (C) and (D) 0.1 mg/mL AB-RNTt (HCl and TFA salts, respectively); (E) 0.1 mg/mL K–RNTm; (F) 0.1 mg/mL K95/RGD5–RNTm; and (G) 0.1 mg/mL KRSR peptide only. Arrows point at nanotubes.

SEM and AFM images revealed dense nanotubular networks for both KRSR–RNTt and AB–RNTt (Figure 4). It is interesting to note that the average length of KRSR–RNTt was less than that of AB–RNTt, suggesting that the bulkiness of the peptide influences the degree of stacking and hence the length of the RNTs.

Figure 4.

SEM (A, C) and AFM (B, D) images of KRSR–RNTt (A, B); and AB-RNTt (C, D).

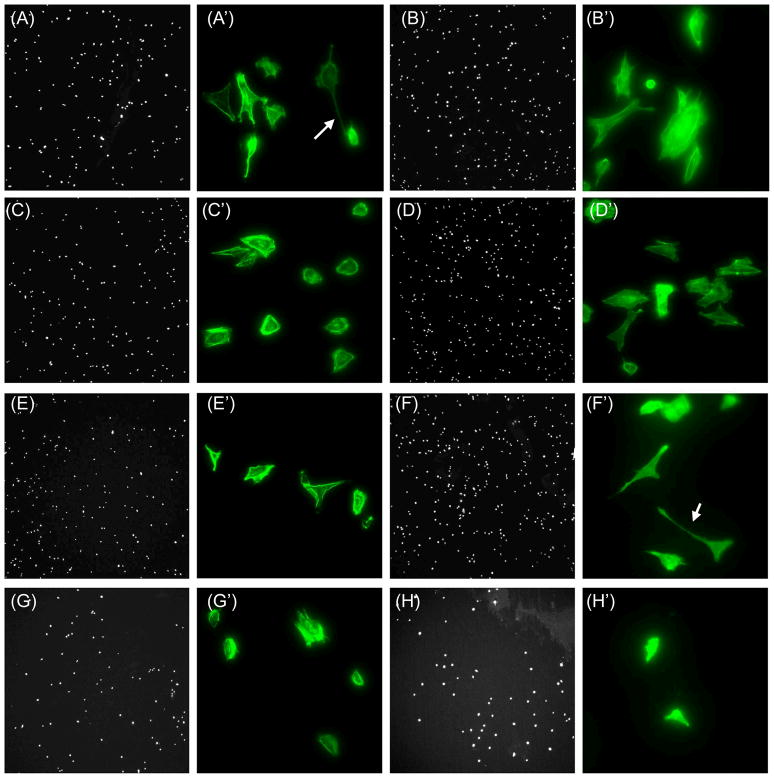

Osteoblast responses to RNT-coated Ti

All of the RNTs coated on Ti significantly enhanced osteoblast adhesion compared to uncoated Ti after 4 h (p<0.01) (Figure 5). Impressively, compared to uncoated Ti, the 0.01 mg/mL KRSR-RNTt and K95/RGD5–RNTm coated Ti improved osteoblast adhesion by 122% and 124%, respectively. In fact, KRSR-RNTt and K95/RGD5–RNTm promoted the greatest osteoblast densities on Ti. In addition, the KRSR peptide alone on Ti promoted more osteoblast cell adhesion relative to uncoated Ti. There was no statistically significant difference among AB-RNTt, K99/RGD1–RNTm, and K–RNTm.

Figure 5.

Osteoblast adhesion on Ti coated with RNTs. Data are mean values ±SEM, N=3. *p<0.01 and &p<0.1 compared to uncoated Ti; **p<0.05 compared to 0.01 mg/mL KRSR coated on Ti; ***p<0.1 compared to 0.01 mg/mL K–RNTm, K99/RGD1–RNTm, AB-RNTt (HCl) coated on Ti; #p<0.05 compared to 0.01 mg/mL K–RNTm coated on Ti; and §p<0.1 compared to K99/RGD1–RNTm, AB-RNTt (HCl or TFA salts) coated on Ti.

It is well-known that surface chemistry of implant materials plays an important role in mediating cell adhesion, proliferation and differentiation [2, 24]. Thus, one of the objectives of this study was to investigate the influence of different surface chemistry (particularly RNTs functionalized with KRSR peptides) on osteoblast adhesion. Balasundaram et al. immobilized KRSR peptides on commercially available nanophase and conventional Ti surfaces and measured improved osteoblast adhesion relative to bare Ti [25]. They found that not only did the KRSR-functionalized Ti have improved osteoblast adhesion relative to uncoated Ti, but that there were more osteoblasts on uncoated nanophase Ti relative to conventional KRSR functionalized Ti. The latter observation underscores the importance of nanostructured biomaterials in improving osteoblast adhesion. In this report, the osteoblast-adhesive KRSR peptide was conjugated with RNTs to provide an improved orthopedic material. The resulting osteogenic RNTs offered a biomimetic nanostructured biomaterial displaying osteogenic peptides that could be readily distributed on the Ti surface to potentially enhance the efficiency of traditional implants. In effect, our results demonstrated that the novel nanotube KRSR-RNTt greatly improved osteoblast adhesion relative to K–RNTm, AB-RNTt, and uncoated Ti, thus, confirming the important role of the osteogenic peptide display function of the RNTs on osteoblast adhesion.

It is also important to note that more osteoblasts adhered to Ti when the latter was coated with KRSR–RNTt versus KRSR. Specifically, osteoblast adhesion on Ti coated with KRSR–RNTt was 84.4% higher than Ti coated with the peptide KRSR alone, which is consistent with earlier results obtained with hydrogels coated with K–RNTm versus poly L-lysine [7]. Additionally, osteoblasts were better spread with more extended filopodia on RNT–coated Ti than on uncoated Ti (Figure 6). Such trends highlight the importance of the unique nano-biomimetic features of RNTs for promoting osteoblast functions.

Figure 6.

Fluorescence microscopy images of osteoblast adhesion on 0.01mg/mL RNT-coated Ti at low magnification (50×, DAPI stained nuclei, A–F) and high magnifications (400×, rhodamine-phalloidin stained F-actin filaments, A′–F′). K–RNTm (A, A′); AB-RNTt (HCl) (B, B′); AB-RNTt (TFA) (C, C′); KRSR–RNTt (D, D′); K99/RGD1–RNTm (E, E′); K95/RGD5–RNTm (F, F′); and KRSR(G, G′). Uncoated Ti at low (H) and high (H′) magnifications. Arrows point to long filopodia.

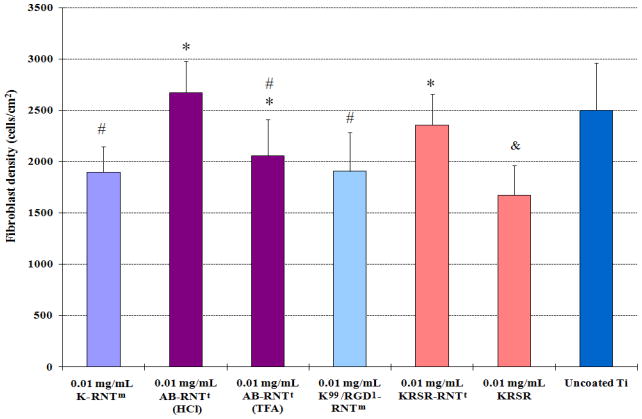

Fibroblast responses to RNT coated Ti

Compared to uncoated Ti, results from the present study provided evidence that KRSR-RNTt, K99/RGD1–RNTm, K–RNTm, and AB-RNTt did not alter fibroblast adhesion after 4 h (Figure 7). Fibroblast attachment on Ti coated with 0.01 mg/mL KRSR-RNTt was slightly greater than the KRSR–coated Ti. Considering a similar surface chemistry but a greatly different supramolecular organization between KRSR-RNTt and the KRSR peptide, this result suggests that the nanostructure of RNTs plays a role in augmenting fibroblast adhesion.

Figure 7.

Fibroblast adhesion on RNT-coated Ti. Data are mean values ±SEM, N=3. *p<0.05 compared to 0.01 mg/mL KRSR coated on Ti; #p<0.05 compared to 0.01 mg/mL AB-RNTt (HCl) coated on Ti; and &p<0.05 compared to uncoated Ti.

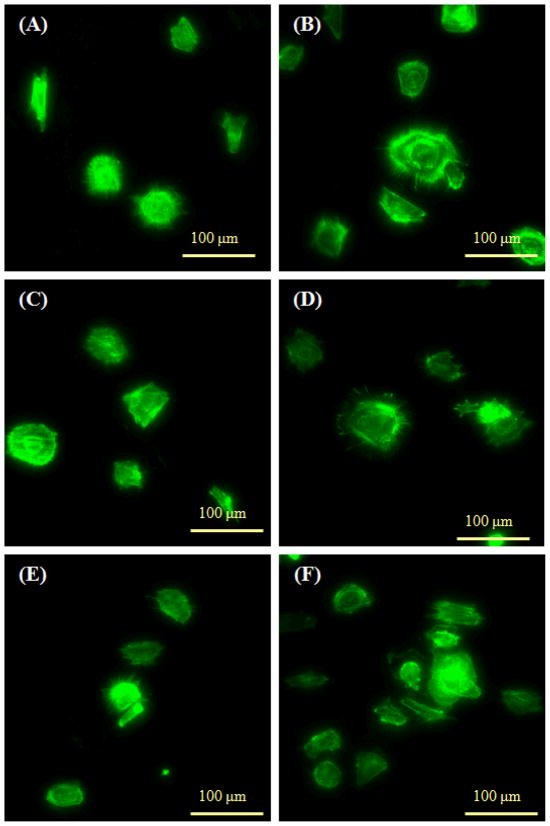

AB-RNTt was assembled from the HCl and TFA salts of AB–(G∧C)2. The differences in fibroblast attachment with these two types of RNTs may be associated with their different counter ions. In contrast with its effect on osteoblast adhesion, the KRSR peptide did not enhance fibroblast adhesion on Ti, thus providing for cell selectivity and a potential for orthopedic applications. Finally, many small filopodia extensions from rounded fibroblasts were visible on all substrates, indicating that fibroblasts attached similarly regardless of the Ti coatings (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Fluorescence microscopy images of fibroblast spreading. (A) K–RNTm coated on Ti; (B) AB-RNTt (HCl) coated on Ti; (C) K99/RGD1–RNTm coated on Ti; (D) KRSR–RNTt coated on Ti; (E) KRSR coated Ti; and (F) uncoated Ti. F-actin filaments were stained by rhodamine-phalloidin.

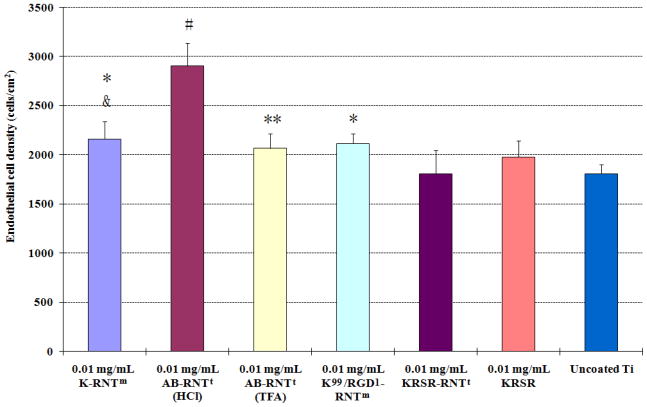

Endothelial cell responses to RNT–coated Ti

Results from this study showed a significantly higher endothelial density on the Ti coated with RNTs (except for KRSR-RNTt) compared to uncoated Ti after 4 h (Figure 9). This result is consistent with a previous report wherein different K–RNT concentrations enhanced endothelial cell adhesion and proliferation on Ti compared to uncoated Ti [26]. In addition, AB–RNTt (HCl) coated Ti promoted the greatest endothelial cell adhesion compared to all other substrates. Furthermore, more endothelial cells attached on Ti coated with K–RNTm and AB–RNTt (HCl) than on Ti coated with KRSR–RNTt. KRSR–RNTt and KRSR peptide coated Ti did not enhance endothelial cell adhesion here, confirming that KRSR selectively promoted osteoblast adhesion as previously described [17]. Endothelial cell morphologies are shown in Figure 10. These results suggested excellent cytocompatibility properties of K–RNTm and RGD–RNTm for endothelial cell adhesion and the selectivity of KRSR–RNTt only for osteoblast adhesion.

Figure 9.

Endothelial cell adhesion on RNT coated on Ti. Data are mean values ±SEM, N=3. *p<0.05 and **p<0.1 compared to uncoated Ti. #p<0.05 compared to all other substrates. &p<0.1 compared to 0.01 mg/mL KRSR–RNTt coated on Ti.

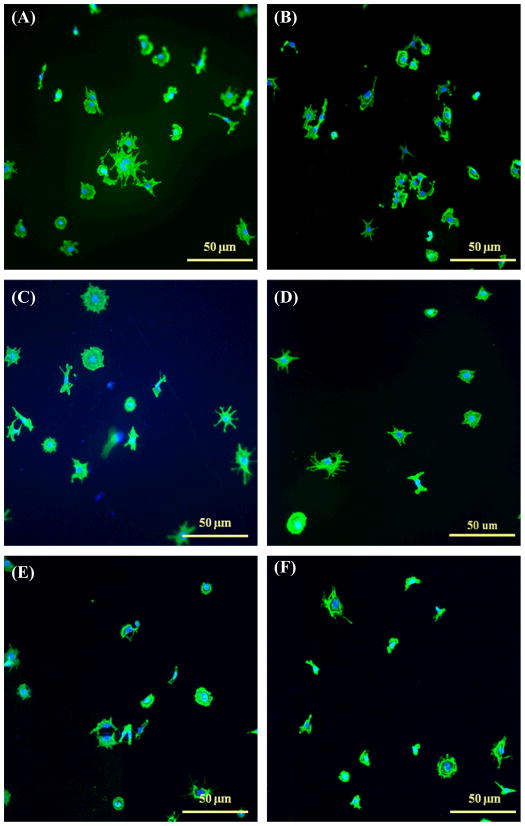

Figure 10.

Fluorescence microscopy images of endothelial cell spreading on various coatings after 4 h. (A) K–RNTm coated on Ti; (B) AB-RNTt (HCl) coated on Ti; (C) K99/RGD1–RNTm coated on Ti; (D) KRSR–RNTt coated on Ti; (E) KRSR coated Ti; and (F) uncoated Ti. F-actin filaments were stained by rhodamine-phalloidin (green color) and cell nuclei were stained by DAPI (blue color).

Enhanced endothelial cell adhesion on RNT coated Ti may be closely related to the nanotubular structure and surface chemistry of RNTs. In fact, other nanomaterials such as polymers and metals improved vascular cell (endothelial and smooth muscle cells) functions compared to conventional (nano-smooth) materials [27]. For example, Choudhary et al. reported greatly improved vascular cell adhesion and proliferation on nanostructured commercially pure Ti particle compacts compared to conventional micron Ti particle compacts [28]. It was speculated in that study that the increased nanoscale roughness and particle boundaries on nanostructured Ti favored endothelial cell functions.

From the surface chemistry point of view, it was reported that poly L–lysine coated vascular stents significantly improved endothelial cell adhesion compared to uncoated controls, perhaps due to the electrostatic or optimal initial protein interactions between poly L–lysine and endothelial cells [29]. In addition, it is well-known that RGD is a cell adhesive domain in many proteins which interacts specifically with integrin receptors of cell membrane receptors to improve the adhesion of a variety of cells [30, 32]. Thus, as supported in this study, a thin film of nanostructured RNTs with numerous K or RGD side chains may alter the surface chemistry and surface roughness of conventional Ti to provide a favorable environment for enhancing endothelial cell adhesion. Due to the advantages of growing new blood vessels in bone formed around an orthopedic implant, the increased endothelial cell functions on RNTs may be an added value for orthopedic applications.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, a KRSR peptide was successfully coupled onto RNTs to serve as a potentially improved orthopedic implant material. Improved cytocompatibility properties of unfunctionalized or functionalized RNTs with KRSR, K, or RGD on conventional Ti were observed. It was found that osteoblast, fibroblast and endothelial cells responded differently on RNTs with different amino acid or peptide side chains. Specifically, greater osteoblast adhesion occurred on KRSR–RNTt and K95/RGD5–RNTm coated Ti than on uncoated Ti, K–RNTm and AB-RNTt coated Ti. In contrast, fibroblast adhesion was similar on the various RNTs compared to uncoated Ti. Furthermore, the various RNTs (except KRSR–RNTt) coated on Ti greatly enhanced endothelial cell densities after 4 h. KRSR–RNTt coated on Ti selectively enhanced the adhesion of bone cells after 4 h. RGD RNTm, K–RNTm and AB-RNTt enhanced both osteoblast and endothelial cell adhesion. In summary, results of this study demonstrated that nanostructured RNTs with diverse amino acid and peptide side chains possess excellent cytocompatibility properties and favorable surface chemistry for selectively enhancing bone cell attachment. While further studies are needed, the ease of chemical modification and presence of a biologically-inspired nanostructured geometry, make RNTs promising materials for improved orthopedic implant applications.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH (Grant #1R21AG027521), the National Research Council of Canada, the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and the University of Alberta. The authors would like to thank Dr Takeshi Yamazaki for generating the molecular models. Dr. Lijie Zhang would like to thank Dr. Kyriacos A. Athanasiou’s for support during manuscript preparation.

References

- 1.American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) online: http://www.aaos.org/Research/stats/patientstats.asp.

- 2.Zhang L, Sirivisoot S, Balasundaram G, Webster TJ. Nanoengineering for bone tissue engineering. In: Khademhosseini A, Borenstein J, Toner M, Takayama S, editors. Micro and nanoengineering of the cell microenvironment: technologies and applications. Norwood: Artech House; 2008. pp. 431–460. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fenniri H, Mathivanan P, Vidale KL, Sherman DM, Hallenga K, Wood KV, Stowell JG. Helical rosette nanotubes: design, self-assembly and characterization. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3854–3855. doi: 10.1021/ja005886l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moralez JG, Raez J, Yamazaki T, Motkuri RK, Kovalenko A, Fenniri H. Helical rosette nanotubes with tunable stability and hierarchy. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:8307–8309. doi: 10.1021/ja051496t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chun AL, Moralez JG, Fenniri H, Webster TJ. Helical rosette nanotubes: a more effective orthopaedic implant material. Nanotechnology. 2004;15:S234–239. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun AL. PhD thesis. Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, Purdue University; West Lafayette, IN: 2006. Helical rosette nanotubes: an investigation towards its application in orthopedics. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang L, Rakotondradany F, Myles AJ, Fenniri H, Webster TJ. Arginine-glycine-aspartic acid modified rosette nanotube-hydrogel composites for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2009;30(7):1309–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L, Rodriguez J, Raez J, Myles AJ, Fenniri H, Webster TJ. Biologically inspired rosette nanotubes and nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite hydrogel nanocomposites as improved bone substitutes. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:17510. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/17/175101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L, Chen Y, Rodriguez J, Fenniri H, Webster TJ. Biomimetic helical rosette nanotubes and nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium for improving orthopedic implants. Int J Nanomedicine. 2008;3(3):323–333. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Journeay WS, Suri SS, Moralez JG, Fenniri H, Singh B. Rosette nanotubes show low acute pulmonary toxicity in vivo. Int J Nanomed. 2008;3:373–383. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalton BA, McFarland CD, Underwood PA, Steele JG. Role of the heparin-binding domain of fibronectin in attachment and spreading of human bone-derived cells. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:2083–2092. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.5.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura H, Ozawa H. Immunohistochemical localization of heparan sulfate proteoglycan in rat tibiae. J Bone Min Res. 1994;9:1289–1299. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650090819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puleo DA, Bizios R. Mechanisms of fibronectin mediated attachment of osteoblasts to substrates in vitro. Bone Miner. 1992;18:215–226. doi: 10.1016/0169-6009(92)90808-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasenbein ME, Andersen TT, Bizios R. Micropatterned surfaces modified with select peptides promote exclusive interactions with osteoblasts. Biomaterials. 2002;19:3937–3942. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webster TJ, Schadler LS, Siegel RW, Bizios R. Mechanisms of enhanced osteoblast adhesion on nanophase alumina involve vitronectin. Tissue Eng. 2001;7(3):291–301. doi: 10.1089/10763270152044152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson M, Balasundaram G, Webster TJ. Increased osteoblast adhesion on nanoparticulate crystalline hydroxyapatite functionalized with KRSR. Int J Nanomed. 2006;1:339–349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dee KC, Andersen TT, Bizios R. Design and function of novel osteoblast-adhesive peptides for chemical modification of biomaterials. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;40:371–377. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19980605)40:3<371::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hemraz U, Fenniri H. Rosette nanotubes: factors affecting the self-assembly of the monobases versus the twin base system. Mater Res Soc Symp Proc. 2008:1057-II05–37. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaiser E, Colescott RL, Bossinger CD, Cook PI. Color test for detection of free terminal amino groups in the solid-phase synthesis of peptides. Anal Biochem. 1970;24:595–598. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, Ramsaywack S, Fenniri H, Webster TJ. Enhanced osteoblast adhesion on self-assembled nanostructured hydrogel scaffolds. Tissue Eng. 2008;14(8):1353–1364. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2006.0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carpino LA, Han GY. The 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl amino-protecting group. J Org Chem. 1972;37(22):3404–3409. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atherton E, Fox H, Harkiss D, Logan CJ, Sheppard RC, Williams BJ. A mild procedure for solid phase peptide synthesis: use of fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl amino acids. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1978:537–539. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merrifield RB. Solid phase peptide synthesis. I. The synthesis of a tetrapeptide. J Am Chem Soc. 1963;85(14):2149–2154. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webster TJ. Nanophase ceramics: the future orthopedic and dental implant material. In: Ying JY, editor. Advances in chemical engineering. New York: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 125–166. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balasundaram G, Webster TJ. Increased osteoblast adhesion on nanograined Ti modified with KRSR. J Biomed Mater Res. 2007;80A:602–611. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fine E, Zhang L, Fenniri H, Webster TJ. Enhanced endothelial cell functions on rosette nanotubes coated titanium vascular stents. Int J Nanomedicine. 2009;4:91–97. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s5589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang L, Webster TJ. Nanotechnology and nanomaterials: promises for improved tissue regeneration. Nanotoday. 2009;4(1):66–80. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choudhary S, Haberstroh KM, Webster TJ. Enhanced functions of vascular cells on nanostructured Ti for improved stent applications. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:1421–1430. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang GX, Deng XY, Tang CJ, Liu LS, Xiao L, Xiang LH, Quan XJ, Legrand AP, Guidoin R. The adhesive properties of endothelial cells on endovascular stent coated by substrates of poly l lysine and fibronectin. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 2006;34(1):11–25. doi: 10.1080/10731190500428283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elmengaard B, Bechtold JE, Soballe K. In vivo study of the effect of RGD treatment on bone ongrowth on press fit titanium alloy implants. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3521–3526. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chua PH, Neoh KG, Kang ET, Wang W. Surface functionalization of titanium with hyaluronic acid/chitosan polyelectrolyte multilayers and RGD for promoting osteoblast functions and inhibiting bacterial adhesion. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1412–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schussler O, Coirault C, Louis-Tisserand M, Al-Chare W, Oliviero P, Menard C, Michelot R, Bochet P, Salomon DR, Chachques JC, Carpentier A, Lecarpentier Y. Use of arginine-glycine-aspartic acid adhesion peptides coupled with a new collagen scaffold to engineer a myocardium-like tissue graft. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2009;6(3):240–249. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]