Abstract

Regulatory T lymphocytes (Treg) expressing the Forkhead Box Transcription Factor 3 (Foxp3) are critical modulators of autoimmunity. Foxp3+ Treg may develop in the thymus as a population distinct from conventional Foxp3− αβ T cells (Tconv). Alternatively, plasticity in Foxp3 expression may allow for the interconversion of mature Treg and Tconv. We examined >160,000 TCR sequences from Foxp3+ or Foxp3− populations in the spleens or CNS of wild type mice with experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE) to determine their relatedness and identify distinguishing TCR features. Our results indicate that the CNS infiltrating Treg and Tconv arise predominantly from distinct sources. The repertoires of CNS Treg or Tconv TCR showed limited overlap with heterologous populations in either the CNS or spleen, indicating that they are largely unrelated. Indeed, Treg and Tconv TCR in the CNS were significantly less related than those populations in the spleen. In contrast, CNS Treg and Tconv repertoires strongly intersected those of the homologous cell type in the spleen. High frequency sequences more likely to be disease associated showed similar results, and some public TCR demonstrated Treg or Tconv-specific motifs. Different charge characteristics and amino acid use preferences were identified in the CDR3β of Treg and Tconv infiltrating the CNS, further indicating that their repertoires are qualitatively distinct. Therefore discrete populations of Treg and Tconv that do not substantially interconvert respond during EAE. Differences in sequence and physical characteristics distinguish Treg and Tconv TCR and imply dissimilar antigen recognition properties.

Introduction

Regulatory T lymphocytes (Treg) expressing the forkhead box 3 (Foxp3) transcription factor are critical modulators of autoimmune diseases (1, 2). Dysfunctional or absent Foxp3 leads to early onset, rapidly progressive multi-organ autoimmunity. Treg can restrain effector T cell responses through the production of immunomodulatory cytokines such as TGF-β, IL-10, and IL-35, expression of inhibitory ligands such as CTLA-4 and LAG-3, cytokine consumption, and direct cytolysis (3). In the context of autoimmunity, immunomodulatory cytokines appear paramount, and in several autoimmune model systems Treg IL-10 and/or TGF-β was essential for regulatory effect (4–8).

Treg form within the thymus as a distinct TCRαβ+ T cell population (natural Treg, nTreg). Additionally, Foxp3 can be upregulated in peripheral Foxp3− T cells (conventional T cells, Tconv) through a TGF-β and IL-2 dependent mechanism that is augmented by retinoic acid and other signals (9, 10). These induced or adaptive Treg (iTreg) have functional similarities with nTreg, and are able to suppress autoimmunity (4, 11, 12). Treg can also downmodulate Foxp3 and even transform into IFN-γ or IL-17 producing effector-type T cells (Teff)(13–15). These may conceivably support autoimmune pathology. The plasticity of Foxp3 expression and extent of interconversion between Tconv/Teff and Treg during immune responses has not been fully elucidated (16).

Tracking of adoptively transferred CD4+CD25− T cells first demonstrated the potential for the upregulation of Foxp3 in Tconv in vivo (17). Subsequent studies have better assessed the magnitude of this. Lathrop et. al. analyzed adoptively transferred CD4+Foxp3− TCRβ transgenic T cells expressing a GFP-Foxp3 marker gene both through Foxp3 expression and TCR repertoire analysis, and estimated that adaptive upregulation of Foxp3 accounts for ~4–7% of the Treg population (18). However, this was significantly increased in the setting of active immunity, specifically T cell transfer into a lymphopenic host. Upregulation of T cell Foxp3 may potentially protect against autoimmunity. Presentation of CNS antigens by neurons induced T cell Foxp3 expression (21). Likewise ectopic expression of CNS antigens outside of the nervous system supported adaptive regulatory T cell generation (22). In each case, the cells were protective in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE). Interestingly, relatively few regulatory T cells infiltrate the CNS early during the course of EAE, though their numbers increase later as disease peaks and recedes (23). This may reflect differences in the kinetics of Treg expansion or recruitment to the CNS. It may also result from adaptive Treg generation among accumulated self-specific T cells.

Loss of Foxp3 has been similarly observed in Treg after transfer into lymphopenic or wild type hosts (10, 19). In the context of autoimmunity, Treg in Rag−/− recipients of mixed Treg/Tconv populations that were then immunized with a myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) peptide showed partial Th17 conversion. Likewise, downmodulation of Foxp3 expression was seen in islet-infiltrating Treg in NOD mice (20). Hence, a body of evidence supports the possibility of bidirectional interconversion between Treg and Tconv populations during autoimmunity.

In contrast, other data fail to find evidence for interconversion during active immune responses. In one analysis, few Foxp3− T cells transferred into mice in which EAE was induced were observed to upregulate Foxp3 (24). Downregulation of Foxp3 on Treg was not analyzed in that system. Two studies employing TCR transgenic mouse models to compare the TCR repertoires of Treg and Tconv during autoimmunity also concluded that interconversion is limited (25, 26). In one, the non-allelically excluded TCRα in TCRαβ transgenic BDC2.5 T cells was analyzed in a diabetes model. In the second, a retroviral transgenic model with a fixed TCRα was used to study EAE. Limited TCR diversity in these systems was experimentally indicated by the low abundance coverage estimator (ACE) values for the studied populations and whether these restricted populations have the same potential for interconversion as substantially more diverse wild type populations is uncertain. In each of the systems the impact of the TCR transgene on T cell development and subsequent history was also unclear. In the retroviral transgenic model, transplantation and subsequent T cell lymphopenia could have further influenced repertoire dynamics.

To circumvent these potential confounding factors associated with repertoire manipulated systems, provide additional evidence on the magnitude of interconversion between Treg and Tconv during autoimmunity, and better understand the T cell response in EAE, we assessed the Treg and Tconv repertoires both in the periphery and the central nervous system (CNS) of wild type C57BL/6 mice with myelin MOG-induced EAE. TRBV13-2+ T cells are highly enriched among MOG-specific T cells (27–29) and we focused on this population, analyzing more than 160,000 TCR in four experiments. Treg and Tconv repertoires in CNS-infiltrating T cells were distinct and showed minimal overlap. Indeed, TCR sequence overlap between Treg and Tconv in the CNS was significantly less than that observed within the spleen. Further, distinct TCR charge and amino acid preferences were identifiable in the different T cell populations, indicative of specificity differences. The amino acid preferences were positional and dependent on total CDR3β length. They were particularly prominent when comparing Foxp3+ and Foxp3− TCR in the CNS and virtually absent when comparing the same populations in the spleen. Our data indicate at most a limited role for interconversion between wild type Foxp3+ and Foxp3− T cells in the autoimmune response. Rather, ontogenically distinct regulatory and effector T cell populations with distinct sequence features predominate during MOG-EAE.

Materials and Methods

Mice

GFP-Foxp3 gene targeted mice on a C57BL/6 background were provided by A. Rudensky (MSKCC)(30) and housed in specific pathogen-free conditions. Experiments were performed in accordance with institutional animal care and use committee guidelines.

Peptides, Antibodies, and Flow Cytometry

MOG35–55 peptide (MEVGWYRSPFSRVVHLYRNGK) was synthesized by the St. Jude Hartwell Center for Biotechnology and HPLC-purified prior to use. CD4-specific antibody (clone L3T4) was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). Flow cytometric sorting was performed on a MoFlo (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA) or iCyt reflection (iCyt, Chamaign, Ill) cell sorter.

EAE induction and clinical evaluation

EAE was induced in GFP-Foxp3 knock-in mice by subcutaneous immunization of 8–10 week old mice with 100 µg of MOG35–55 peptide in complete Freund's adjuvant containing 0.4 mg Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37RA (Difco, Lawrence, KS). 200 ng pertussis toxin (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, CA) was administered i.v. on days 0 and 2. Clinical scoring was: 1, limp tail; 2, hind limb paresis or partial paralysis; 3, total hind limb paralysis; 4, hind limb paralysis and body/front limb paresis/paralysis; 5, moribund. Mice were sacrificed and analyzed on day 14 or 15 after immunization.

Cell Isolation

Splenic or CNS (combined brain and spinal cord) cells were isolated as described (4) and enriched for CD4+ cells using MACS separation columns per manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi, Auburn, CA). Cells were stained with APC anti-CD4 antibody and the entire cell content obtained from each organ flow cytometrically sorted for CD4 and GFP-Foxp3 positivity (Treg) or negativity (Tconv).

RNA isolation, cDNA transcription and amplification

Sorted cell populations were lysed and total RNA isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA was produced using the Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen) per manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was amplified with Cβ (5’-GGGTGGAGTCACATTTCTCAGATC) and Vβ8.2 (5’-CCCCCTCTCAGACATCAGTGTAC) specific primers using the High Fidelity PCR System (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The ~200 bp PCR product was purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and column purification (Qiaquick gel extraction kit, Qiagen).

DNA preparation and sequencing

DNA end repair was performed by incubating the purified PCR products with 15 U T4 DNA polymerase (NEB), 50 U T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (NEB), 0.4 mM dNTP, T4 ligase buffer with 10 mM dATP (Promega, Madison, WI), and 5 U Klenow enzyme (Promega) for 30 min. at 20 C. The product was purified using the Qiaquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). To adenosine tag the DNA 3’ ends, purified DNA was incubated with 25 U Klenow fragment (3’ to 5’ exo minus) (NEB, Ipswich, MA), Klenow buffer, and 0.2 mM dATP for 30 min. at 37 C. The product was purified and concentrated to 10 µl using the MinElute Reaction Cleanup Kit (Qiagen). Next, sequencing adapters were ligated onto the PCR products, using 3 µM Index PE adapter Oligo Mix, 5 µl Quick DNA ligase (NEB), and ligase buffer and incubated for 15 min. at 20 C. To remove unligated adapters, the product was purified using the Qiaquick PCR purification Kit (Qiagen) and agarose gel-purified as above. InPE 1.0 and 2.0 and Index primers (Illumina, San Diego, CA) were next linked to the DNA using the Phusion DNA Polymerase Kit (Finnzymes Oy) and the PCR products purified using the Qiaquick kit. Sequencing was performed with an Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx sequencer and 125 bp (plus 6 bp barcode) reads obtained, covering the entire CDR3β region. Vβ, Jβ, and CDR3 were identified per IMGT (Immunogenetics Information System; www.imgt.cines.fr) sequence information. Hydropathy indices were calculated according to Kyte and Doolittle (31). Alignments were performed using Clustal W (ver. 2) software (32).

Statistics

One and two way ANOVA were calculated using Prism software (GraphPad, LaJolla, CA). If the data was not normally distributed, the Mann-Whitney U test (Prism) was used. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant, except for analyses of amino acid preferences in CDR3 where only differences with a p < 0.01 are reported. P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction (Prism). Means ± 1 s.d. are displayed except where indicated. Morisita-Horn indices and abundance coverage estimator (ACE) analyses were calculated with EstimateS software (25, 33, 34). The upper limit of 95% confidence interval (CI) of the maximum frequency (ϕmax) of an unobserved TCR CDR3 transcript in a sample was calculated using the estimation of binomial parameter (StatXact-8 8.0.0, Cytel Studio), and the upper limit of 95% CI of the Blyth-Still-Casella estimation reported.

Results

Isolation of TRBV13-2+ TCR

MOG35–55-specific T cells are biased toward the use of TRBV13-2+ TCRβ (24, 28). In contrast, a comparison of T cell response by splenocytes, draining LN cells, or non-draining LN cells from CFA-immunized or unimmunized mice did not demonstrate this bias either directly ex-vivo or after in vitro re-stimulation with H37Ra-strain M. tuberculosis (data not shown). EAE was induced in GFP-Foxp3 knock-in mice by immunization with MOG35–55 in CFA. In four analyses, CD4+ GFP-Foxp3+ or CD4+ GFP-Foxp3− T lymphocytes were flow cytometrically sorted from the CNS or spleen of individual mice with EAE and disease scores of 2–3 (Table I).

Table I. Characteristics of analyzed T cell populations and TCR sequences.

Disease scores of mice, numbers of cells isolated after flow cytometric sorting, and numbers of TRBV13-2 sequences acquired, both total and unique, for individual populations are listed. The ACE value, an indication of sequence diversity, was calculated based on an n=10 for infrequent sequences. ϕmax indicates the frequency threshold for which analytic coverage is adequate for a 95% confidence of sequence detection.

| Experiment | Disease score |

Cell type | Cells collected (×103) |

Total Sequences |

Unique Sequences |

ACE (n=10) |

ϕmax (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | Spleen Foxp3− | 3600 | 10519 | 7049 | 26814 | 0.049 |

| Spleen Foxp3+ | 200 | 4377 | 1866 | 5031 | 0.19 | ||

| CNS Foxp3− | 92 | 11297 | 1892 | 5112 | 0.18 | ||

| CNS Foxp3+ | 10 | 8376 | 918 | 2650 | 0.38 | ||

| 2 | 2 | Spleen Foxp3− | 2900 | 11103 | 7823 | 38249 | 0.044 |

| Spleen Foxp3+ | 150 | 7629 | 2441 | 5955 | 0.14 | ||

| CNS Foxp3− | 83 | 1709 | 510 | 1450 | 0.68 | ||

| CNS Foxp3+ | 12 | 18620 | 1267 | 3363 | 0.27 | ||

| 3 | 3 | Spleen Foxp3− | 2700 | 10657 | 6457 | 25137 | 0.054 |

| Spleen Foxp3+ | 280 | 7384 | 2159 | 5492 | 0.16 | ||

| CNS Foxp3− | 150 | 13312 | 959 | 2270 | 0.36 | ||

| CNS Foxp3+ | 19 | 13722 | 1817 | 5900 | 0.19 | ||

| 4 | 3 | Spleen Foxp3− | 2800 | 7939 | 5824 | 30352 | 0.060 |

| Spleen Foxp3+ | 210 | 13480 | 4006 | 9357 | 0.086 | ||

| CNS Foxp3− | 77 | 15160 | 1835 | 4406 | 0.19 | ||

| CNS Foxp3+ | 18 | 5471 | 904 | 3109 | 0.38 | ||

| Total sequences acquired | 160,755 | ||||||

| Sum of unique sequences in individual groups | 47,627 | ||||||

| Total unique sequences acquired | 38,723 | ||||||

TRBV13-2+ Vβ-Cβ segments were amplified from cDNA using specific primers and sequenced. In total, 160,755 sequences spanning the Vβ-Cβ were acquired from the four experiments. Amongst these, 38,723 unique sequences were identified in the combined data set. Within an individual experiment and population group, GFP-Foxp3+ or GFP-Foxp3− and splenic or CNS, the average sequence was identified ~3.4 times. 18.7% of unique sequences identified in individual populations were shared, either between population groups in a single experiment or between experiments. TRBV13-2+ sequence numbers collected for the different cell populations varied (Table I; median for all populations: 10,588, mean±1 s.d.: 10,047±4333). The saturation sequencing led to a high level of sequence coverage. ϕmax values indicated a 95% confidence for detecting sequences with representation frequencies ranging from 0.044% – 0.68% for the individual cell populations and experiments (overall mean±1 s.d.: 0.21±0.17%).

ACE analysis indicated substantial repertoire diversity that differed for the individual populations. The largest mean ACE value was for the largest cellular population, splenic CD4+ Foxp3− T cells (30,138±5,827). This was followed by splenic Foxp3+ (6,459±1,969), CNS Foxp3+ (3,756±1,460), and CNS Foxp3− (3,309±1,731) CD4+ T cells. These values contrasted with abundance estimates in the hundreds previously described when repertoire-restricted TCR transgenic and retrogenic mice were analyzed (25, 26, 34, 35), reflecting increased repertoire diversity in wild type mice. The diversity of the Foxp3+ T cell repertoire is noteworthy, as despite a total population size only about that of Tconv, estimated Treg and Tconv repertoire diversities were similar in the CNS and Treg diversity was ¼ – ⅕ that of Tconv in the spleen. Studies of mice with repertoires limited by transgenic expression of one or two TCR chains also identified an enriched Treg repertoire, with Treg repertoires of similar or even increased size compared with Tconv despite smaller overall Treg population sizes (25, 35, 36). This indicates that the Treg repertoire has a greater diversity relative to its population size than Tconv, and implicitly that the clonal population size of individual Treg is smaller than that of Tconv.

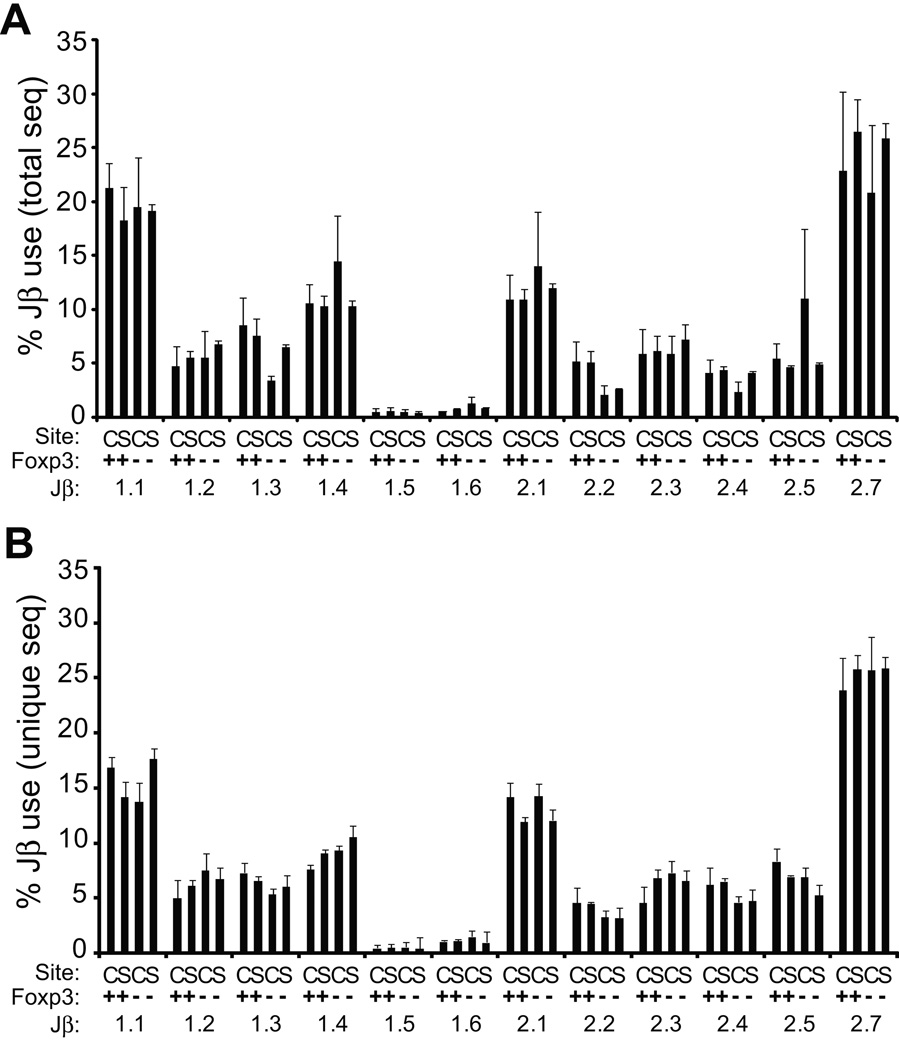

Similar TCR Jβ use in Treg and Tconv during EAE

As a low resolution survey for variation in TCR gene use, we analyzed the distribution of Jβ chains within the TRBV13-2+ Treg and Tconv populations. The overall frequency of the different Jβ showed substantial variability, with Jβ2.7 most and Jβ1.5 least common (Fig. 1a). Although some variation was observed between individual experiments in the use of specific Jβ, use was not significantly different across the population groups (p>0.05). This indicates that the overall frequency of individual Jβ chains is equivalently distributed among regulatory and non-regulatory populations in the CNS and spleen.

Figure 1. TCR Jβ use by TRBV13-2+ T cells in MOG-EAE.

(A) The frequency of Jβ use among total TCR within an individual population, CNS (C) or splenic (S) and Foxp3+ (+) or Foxp3− (−), is tallied. Mean + 1 s.e.m. for results from the four experiments is plotted. (B) Analyses were performed as in (A) except TCR Jβ use was analyzed for unique sequences only. No significant differences were observed in the frequency of any TCR Jβ between splenic or CNS Treg or Tconv populations in either analysis.

Jβ use among total sequences will be influenced by the representation frequency of individual TCR sequences, and thus biased toward dominant TCRs present within each population. An identical analysis was therefore performed in which Jβ use was tallied only for unique TCR sequences (Fig. 1b). Here too, no differences in Jβ use were seen among the population groups. Therefore, Jβ representation among CD4+ T cell populations, Foxp3+ or Foxp3− and CNS or splenic, is similar in C57BL/6 mice with MOG-EAE.

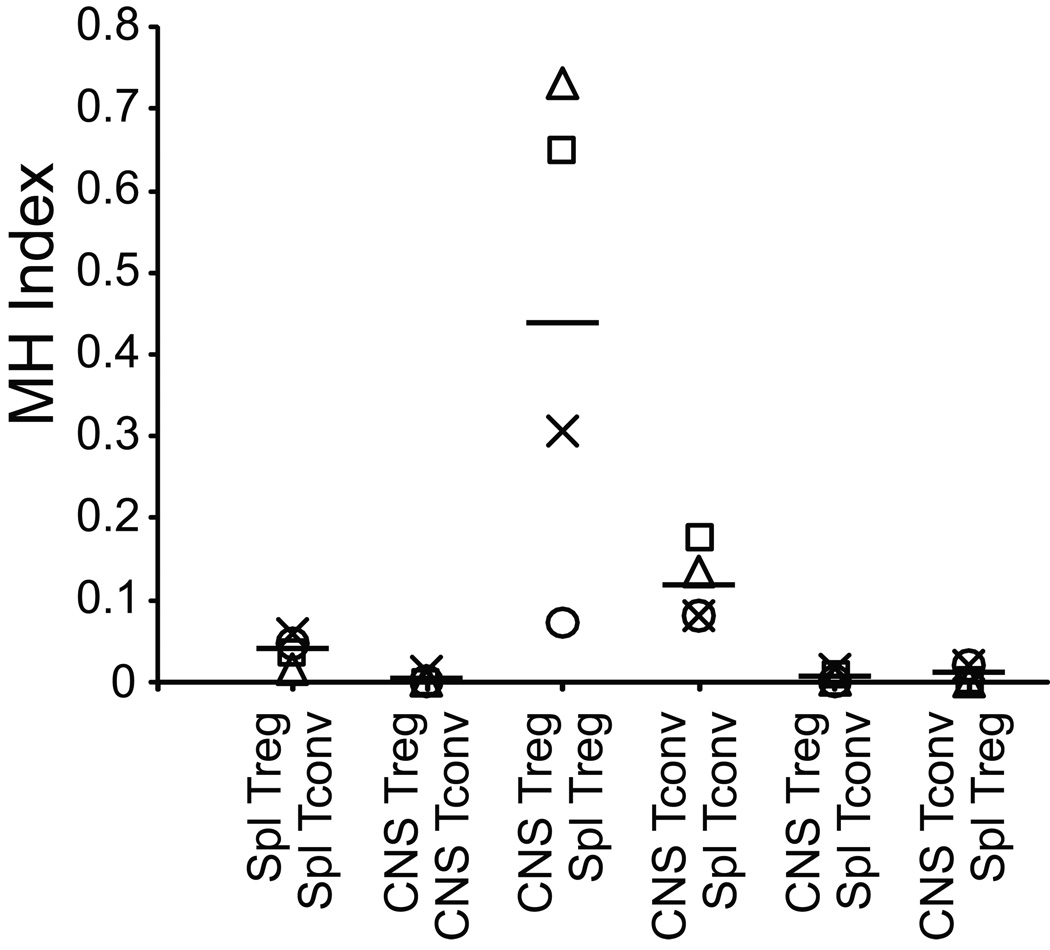

Distinct Treg and Tconv CDR3 use in EAE

To assess the Treg and Tconv TCR repertoires at higher resolution, we next compared the amino acid sequences of their CDR3β. CDR3 representation among populations was assessed using the Morisita Horn (MH) index, a measure of biologic diversity that incorporates differences in both species frequency and richness (Fig. 2). The index varies from 0, indicating absence of overlap, to 1.0, indicating population identity. Consistent with previous reports studying the repertoires of mice transgenic for a single TCR chain, Treg and Tconv in the spleen showed a low level of overlap with MH values ranging from 0.017 to 0.060 (mean±1 s.d.: 0.041±0.018). If TCR use was mirrored in the CNS-infiltrating cell populations, a similar degree of overlap would be expected. However, consistently across the four experiments, CNS infiltrating Treg and Tconv demonstrated diminished MH values compared with the same populations in the spleen (range: 0.001–0.013; mean±1 s.d.: 0.0045±0.0006; Mann Whitney test, p=0.029). Therefore TCR from Treg and Tconv infiltrating the CNS show little similarity, and significantly less overlap than the equivalent populations in the spleen.

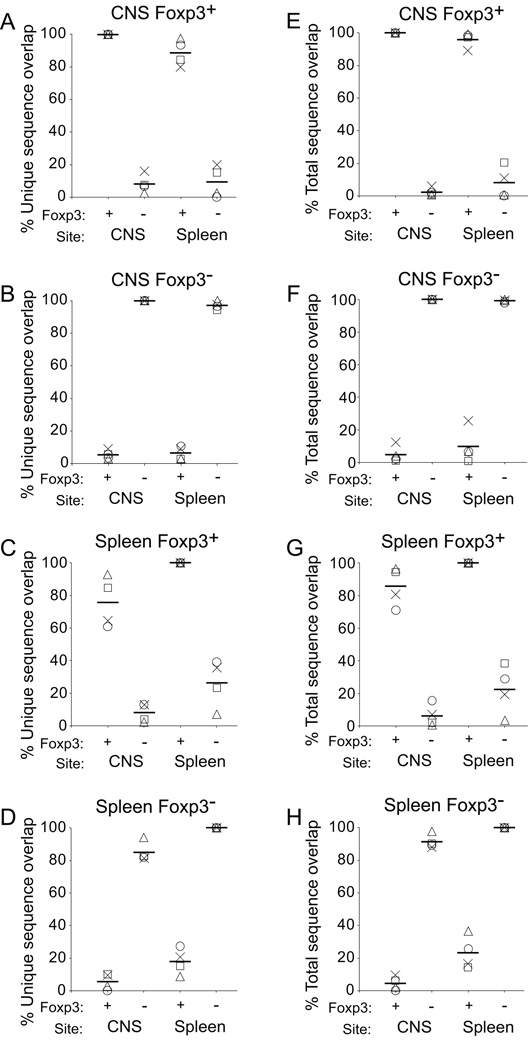

Figure 2. Relatedness of TCR population groups.

Relatedness of pairs of population groups was assessed using the Morisita Horn Index. Results from individual experiments are indicated by distinct symbols (○, ∆, X, □). Means are indicated by the horizontal bar. Index values range from 0, wholly unrelated, to 1, identical.

The non-overlapping Treg and Tconv TCR repertoires in the CNS indicated that the Foxp3+ and Foxp3− populations were not substantially interconverting at this site. In the most simple scenario, a subset of T cell clones present in the spleen that discriminately express Foxp3 migrate into the CNS. Foxp3 expression among these cells remains stable there. Alternatively, interconversion between Treg and Tconv may be occurring in the periphery. Differential migration of Foxp3+ and Foxp3− cells among a clone occurs, and the phenotype of those cells remains stable in the CNS. Finally, rapid interconversion may occur with cell entry into the CNS. In this circumstance, the CNS microenvironment would have to enforce a particular Foxp3 expression profile based on T cell specificity. In all scenarios, Foxp3 expression would need to remain fixed in individual expanding clones within the CNS to explain the highly discrete populations observed there.

In the first model, interconversion is not substantial in the spleen or CNS, and CNS Treg TCR sequences should strongly overlap with those of splenic Treg but not splenic Tconv. Likewise, CNS Tconv TCR should overlap with splenic Tconv but not Treg TCR. In the latter models interconversion occurs in the periphery or rapidly upon CNS migration, and a greater degree of overlap would therefore be anticipated between CNS Treg and splenic Tconv, or between CNS Tconv and splenic Treg.

Comparison of CDR3s expressed by the CNS populations of Treg or Tconv, with the same or alternate populations in the spleen supported only the first model (Fig. 2). CNS Treg TCR were highly related to splenic Treg TCR. MH indices comparing these groups ranged from 0.074–0.731 (mean±1 s.d.: 0.44±0.31). This differed from the minimal relationship between CNS Treg and splenic Tconv (range: 0.001–0.017, mean±1 s.d.: 0.0080±0.0007, p=0.029). Similarly, CNS Tconv TCR showed strong overlap with splenic Tconv TCR (range: 0.081–0.178; mean±1 s.d.: 0.12±0.05) but little with Treg TCR (range: 0.002–0.021, mean±1 s.d.: 0.011±0.01, p=0.029). Therefore, CNS-infiltrating Treg and Tconv populations are distinct. Further, these populations show strong resemblance exclusively to the corresponding population in the spleen.

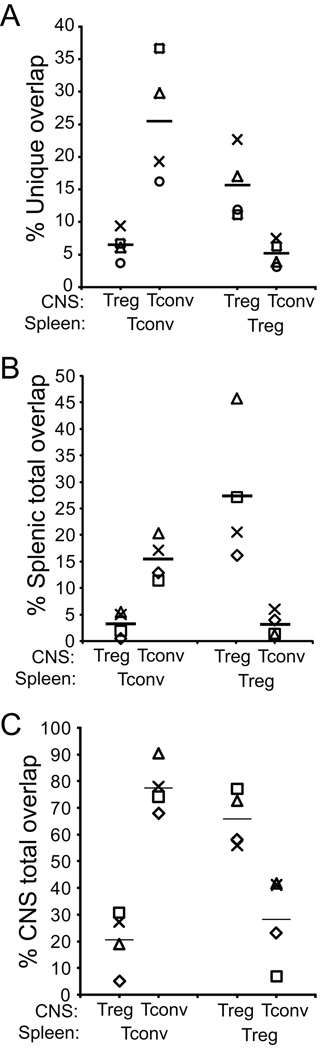

Overlap of CDR3 sequences

The MH statistic explores concordance of both species and frequency in populations. We also examined the overlaps of sequences acquired without regard to the relative frequencies of individual sequences in the comparison groups. In this analysis a sequence present at high frequency in one population and even once in the comparison group is counted equivalently to sequences present at high frequency in both groups. To examine species overlap alone, we calculated the percent of unique TCR sequences within a cohort that were shared by alternative populations. Numbers of unique sequences differed between population groups and experiments (Table I), with the splenic Foxp3− population showing the greatest number followed by splenic Treg and the CNS populations. This complicates comparisons, as the total potential for shared sequences increases as the diversity of the comparison population grows. Nevertheless, the mean number of unique CNS Tconv and CNS Treg sequences were similar (mean±1 s.d.: 1299±677 and 1227±428), and therefore comparison of these CNS infiltrating cells with single splenic populations was possible. Paralleling the MH index findings, unique CNS Tconv sequences showed greater overlap with the splenic Tconv sequences than did the CNS Treg sequences (Fig. 3a; mean±1 s.d.: 25.5±9.5% of CNS Tconv vs 6.5±2.3% of CNS Treg, Mann Whitney p=0.029). Likewise, unique CNS Treg sequences showed greater overlap with splenic Treg sequences than did CNS Tconv sequences (15.7±5.3% of CNS Treg vs 5.2±2.0 of Tconv; p=0.029).

Figure 3. Overlap frequency of unique TCR sequences among population groups.

(A) The percent of unique TCR sequences identified among CNS Treg or Tconv that were also identified in the comparison population in the spleen is plotted. Results from individual experiments are identified by distinct symbols and means by horizontal bars as in Fig. 2. (B) Analysis was performed as in (A) except total numbers of sequences identified in the splenic population that are also present at any frequency in the indicated CNS population is plotted. (C) Analysis as in (A, B) except total numbers of sequences identified in the CNS population that are also present at any frequency in the indicated splenic population is plotted.

Similar findings were obtained when total sequence events were compared (Fig. 3b, c). Total splenic Tconv sequences showed greater overlap with sequences present at any frequency among CNS Tconv compared with CNS Treg (15.4±4.1% vs 3.2±2.4%; p=0.029). Splenic Treg sequences also showed more overlap with CNS Treg than CNS Tconv sequences (27.5±13.0% vs 3.1±2.2%, p=0.029). In a similar manner, the total percent of CNS Tconv sequences overlapping with splenic Tconv was greater than that of CNS Treg (77.7±9.5% vs 20.6±11.4%; p=0.029), and CNS Treg overlapped at a higher frequency with splenic Treg than did CNS Tconv (66.0±10.5% vs 28.3±16.6%; p=0.029). Hence TCR sequences, tallied either as total events or unique species and assessed without regard to the relative frequency of identification in the comparison group, showed significantly greater overlap within a cell type across organs, Foxp3+ or Foxp3−, than across cell types.

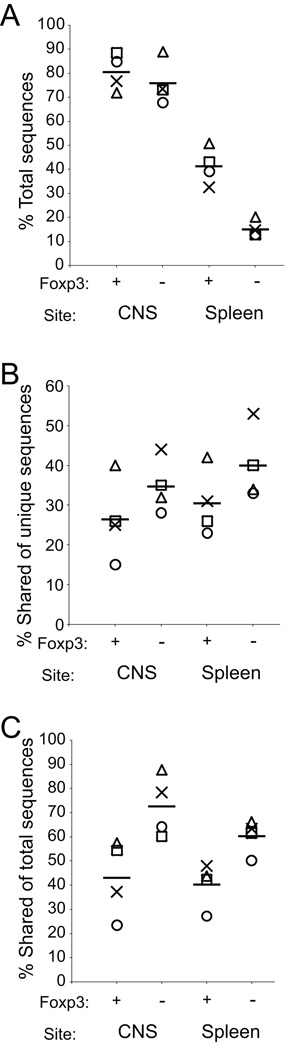

Analysis of high frequency sequences

TCR expanded during the autoimmune response will be present at increased frequency. To focus on these TCR, we additionally analyzed the ~100 most common TCR in each population group from each experiment. These high frequency cohorts, though incorporating only a small fraction of the unique sequences, comprised a disproportionately large proportion of the total sequences identified in each population group. This varied for the different populations, with the “top 100” unique sequences accounting for a mean of 15.1% of total sequences acquired among splenic Foxp3− TCR up to 80.4% among CNS Foxp3+ cells (Fig. 4a). These wide ranging values mirrored the differences in the total diversity of the cell populations. Population diversity, as indicated by numbers of unique sequences, ranked as splenic Tconv>splenic Treg>CNS Tconv~CNS Treg (Table I). The percent of total sequences included within the “top 100” cohorts ranked in the opposite direction with CNS Treg~CNS Tconv>splenic Treg>splenic Tconv. Indeed, the mean frequencies for splenic Tconv, splenic Treg, CNS Tconv, and CNS Treg among the “top 100” sequences were respectively 9.1, 9.6, 7.1, and 8.9 fold greater than would be expected had the frequency of all sequences within each cohort been equal. Therefore these sequence cohorts are enriched in very high frequency sequences, and the magnitude of this enrichment is similar in the different population groups.

Figure 4. Analysis of high frequency TCR sequences.

Sequences were sorted based on frequency within a population group and experiment and the ~100 most frequent sequences for each cohort analyzed. If >1 sequence shared the cutoff “100th most common” frequency, they were included in the high frequency cohort. (A) Frequency representation of the “top 100” sequences among the total sequences within a cohort is shown. (B) The number of unique “top 100” sequences within an individual experiment that were shared with sequences present in other “top 100” cohorts, CNS or splenic and Foxp3+ or Foxp3−, is plotted. (C) The percent of the total sequences included in the “top 100” groups that were shared with sequences present at any frequency in other cohorts is shown. Individual experiments are indicated by distinct symbols and means among the experiments by horizontal bars.

Among the high frequency sequences, many were shared among other high frequency cohorts within an experiment; means of 40±9%, 30±8%, 35±7%, and 26±10% of unique sequences from the “top 100” splenic Foxp3−, splenic Foxp3+, CNS Foxp3−, and CNS Foxp3+ T cells respectively were shared with at least one other TCR population (Fig. 4b). An even greater degree of sharing was observed when the frequency of total, rather than unique, sequences among the “top 100” cohorts was surveyed (Fig. 4c). Therefore, TCR subsets that include the highest frequency sequences within an experimental population also show substantial overlap with high frequency sequences in other population groups.

More interestingly, analyses of these overlap sequences demonstrated strong concordance between cells of a single phenotype, Foxp3+ or Foxp3−, present in spleen and CNS. This was true both for the numbers of unique sequences that overlapped and for the overall frequency of these populations (Fig. 5a–h). A much lower degree of overlap among the “top 100” cohorts was seen when sequences were compared across cell types, regardless of their location. For example, 89±8% of the unique “top 100” CNS Foxp3+ sequences that were shared by any other high frequency cohort were present in the splenic Foxp3+ cohort (Fig. 5a). This also comprised 96±5% of the total number of shared sequences within that cohort (Fig. 5e). In contrast, only 8±6% and 9±10% of these same unique sequences were observed in the CNS Foxp3− and splenic Foxp3− groups respectively, reflecting 2±2% and 8±10% of the total shared CNS Foxp3+ sequences. Therefore, consistent with the MH analyses on total populations (Fig. 2), the population overlap of high frequency sequences is substantially greater between a single cell class, Foxp3+ or Foxp3−, across organs than between different cell classes. This affirms the close relationship between cells of a single type, Foxp3+ or Foxp3−, present at different locations, and further supports the conclusion that interconversion between the Treg and Tconv populations plays a limited role in supplying the respective populations.

Figure 5. Analysis of shared high frequency TCR sequences.

The intersection between shared high frequency sequences from CNS or splenic and Foxp3+ or Foxp3− populations within individual experiments was analyzed. The ordinate indicates the percent of unique (A–D) or total (E–H) shared TCR sequences within the “top 100” cohorts listed on the subfigure titles that were also identified in the “top 100” populations indicated on the abscissa. The cohorts will always have 100% overlap with the identical TCR cohort, and this is apparent in the individual plots. Individual experiments are indicated by distinct symbols and means by horizontal bars.

Public TCR sequences

The conserved preference for TRBV13-2 in MOG-EAE indicates that this Vβ is itself pathologically relevant. Although in our analysis the TCRα partners are unknown for the individual sequences and may vary between experiments, the saturation sequencing performed here provides the opportunity to assess for the presence of public TCRβ sequences at high resolution.

A prior study examined TCRβ repertoire using immunoscope analysis in Tconv from mice with MOG-EAE and, though sequence numbers were small, several shared and private TRBV13-2+ CDR3β sequences were identified (37). A single CDR3β sequence was seen in all mice analyzed, ASGETGGNYAEQ. This proved to be overall the fourth most common public sequence in our pooled TCR data set, was primarily present in CNS-infiltrating T cells, and though predominantly Foxp3− was shared by Foxp3+ and Foxp3− populations (Suppl. Table I). Two additional shared though not ubiquitously observed TCR in that study were ASGETGGVYAEQ and ASGDVLGGGAEQ. The former was observed in 3 of the 4 mice we analyzed and, in the CNS, present only in the Foxp3− populations. The latter was observed at high frequency in the Foxp3− CNS population only of experiment 1. Of an additional 8 private TCR they identified, 4 were present in our analyses, each in a single experiment. Further, of 2 additional Tconv sequences we have previously validated (38), 1 was present in 2 of the 4 experiments, exclusively in the Foxp3− subsets. Hence, our data contains a substantial number of TRBV13-2+ sequences previously identified in association with EAE, including 3/3 sequences identified as public or shared and 5/10 previously considered private. This implies a common association of these TCR with EAE and validates the more general representation of the sequences we observed in EAE.

A total of 38,723 unique sequences were identified within the four experiments. Of these 3874 or 10.0% were shared between experiments. Most of these sequences, 2682 (6.9%), were shared between two experiments, 784 (2.0%) were seen in 3, and 408 (1.1%) were present in all 4 experiments. TCR seen primarily in the CNS are more likely than primarily splenic TCR to be disease relevant. Among CNS dominant sequences, roughly half were primarily Foxp3+, specifically 50% of private sequences, 41% of sequences shared in 2 experiments, 38% shared in 3, and 47% shared in 4. Overall, this indicates that public sequences in the CNS are not associated with a particular cellular lineage, Foxp3+ or Foxp3−.

We next assessed the relatedness of the public sequences. Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis of CNS infiltrating T cell TCR shared in all 4 experiments demonstrated considerable overlap between predominantly Foxp3− and Foxp3+ sequences, though also clustering of some Foxp3+ and Foxp3− sequences into distinct groups (Suppl. Fig. 1). For example, 6/43 of the primarily Foxp3− sequences were 13 residues long and shared a common ASGETGGX(Y/F)(A/S)(E/G)QF motif. Similarly, 5/38 of the CNS Foxp3+ sequences were 8 residues long and shared an ASGX(D/Y)E(Q/K)Y motif. The presence of discernible and distinct Foxp3+ and Foxp3− sequence motifs implies that conserved sequences are important in defining the public TCR repertoires in MOG-EAE for these different populations.

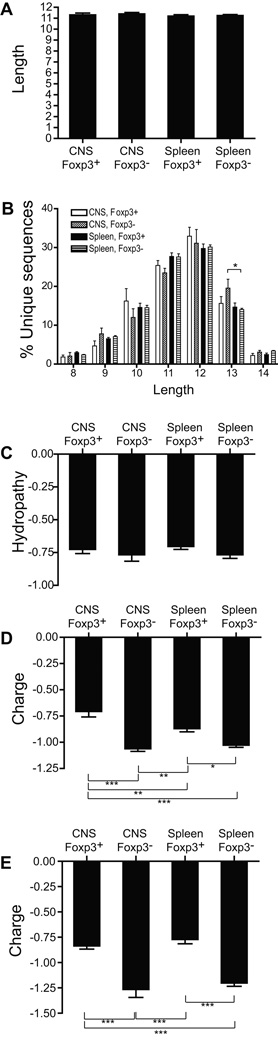

Structural features of TCR

To determine if structural features of CDR3β correlated either with cell type or localization, we analyzed their lengths, hydopathy indices, and charge. Mean length did not significantly differ among the sequences within the different cohorts (Fig. 6a). Likewise, the distribution of lengths used was largely similar (Fig. 6b). Average hydropathy also did not significantly differ among the cohorts (Fig. 6c). Interestingly, mean charge did vary (Fig. 6d). TCR from the CNS Foxp3+ cohort had significantly diminished negative charge when compared with all other cohorts. The splenic Foxp3+ cohort also had a decreased negative charge compared with the CNS and splenic Foxp3− cohorts, though to a lesser extent than the CNS Foxp3+ TCR. Therefore, the Treg and Tconv TCR display distinct charge characteristics, with more substantial differences in the CNS than in the splenic populations.

Figure 6. Physical properties of TCR sequences.

(A) The average CDR3 length, corresponding to the number of amino acids exclusive of the C and F border residues, for unique TCR from the indicated population groups was calculated. Mean values from the 4 experiments are plotted. (B) To better identify differences in the distribution of CDR3 lengths in each population, mean percentages of unique TCR from the indicated population groups that contain a CDR3β of the indicated length is plotted. Average Kyte Doolittle hydropathy (C) and charge (D) of unique sequences, and charge of “top 100” high frequency sequences (E) is plotted as in (A). Mean + 1 s.e.m. of values from the 4 independent experiments are plotted. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

The decreased negative CDR3 charge among Foxp3+ sequences was also apparent when only the most common sequences in each cohort were analyzed (Fig. 6e). In contrast to the larger sequence populations, these more circumscribed cohorts no longer showed a significant charge difference between the Foxp3+ TCR present in the spleen and CNS, as both showed similar decreases in negative charge compared with the Foxp3− populations. As with total TCR populations (Fig. 6a, c), no differences in length or hydropathy were seen in these high frequency sequence cohorts (not shown). Therefore CDR3β charge characteristics distinguish the Foxp3+ and Foxp3− T cell populations in EAE.

Sequence variations distinguish T cell cohorts

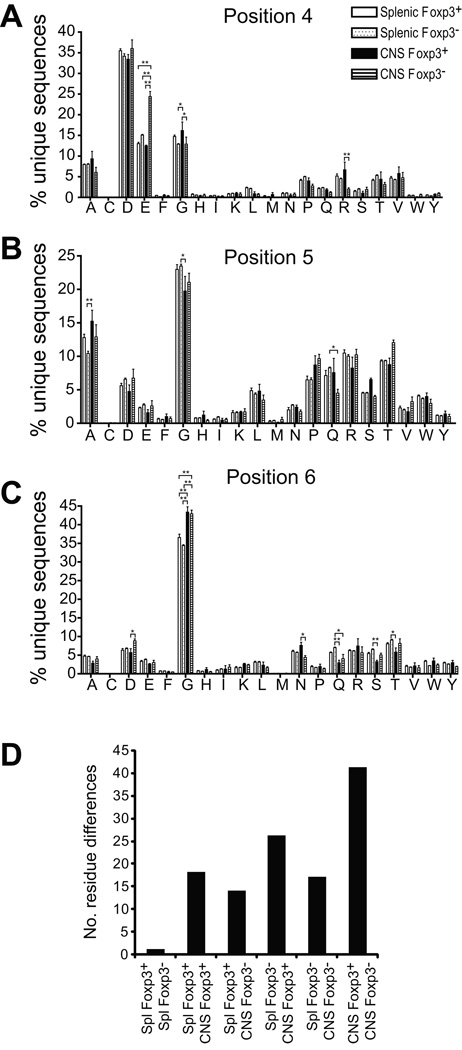

To further probe the differences in TCRβ used by the different T cell cohorts, we assessed the amino acid composition of their CDR3β. The first and last 3 residues of the CDR3 are buried and not directly engaged in antigen binding. We thus focused on the amino acid composition of residues 4–6, all of which will be within the surface exposed loop for CDR3β of lengths >8, which comprised the large majority of the TCR we identified (Fig. 6b). Preferential amino acid use was apparent. For example, analysis of CDR3β position 4 demonstrated an increased use of E in CNS Foxp3− T cells; 13.0±0.7%, 15.1±0.3%, and 12.5±0.3% of CDR3β incorporated an E at this position in splenic Foxp3+, splenic Foxp3− and CNS Foxp3+ populations versus 24.4±2.4% of CNS Foxp3− CDR3 (Fig. 7a). A more modest increase in the use of R at the same position in CNS Foxp3− cells and of G in CNS Foxp3+ cells was also seen. Likewise, significantly increased use of G was observed at position 6 in both CNS infiltrating Foxp3+ and Foxp3− populations when compared with the respective splenic populations (Fig. 7c). This indicates that sequence variations at specific CDR3β residues are present and consistently identifiable among populations of T lymphocytes.

Figure 7. Positional amino acid use in CDR3β.

(A–C) The distribution of amino acids incorporated at the indicated residue (no. 4–6) of the unique CDR3β sequences identified in the indicated populations is plotted. Mean + 1 s.e.m. of values from the 4 independent experiments is shown. *, p<0.01; **, p<0.001. (D) Analyses as in (A–C) were performed for CDR3β amino acids at least 4 residues from the terminal C and F, and therefore anticipated to engage pMHC. Assessments were performed for each population group segregated by length (Suppl. Fig. 2). A total of 700 comparisons were made between the population groups, CNS or splenic and Foxp3+ or Foxp3−, (20 amino acids x 35 independent comparisons of individual residues for CDR3 8–14 amino acids long) by 2-way ANOVA. Numbers of statistically significant differences with a p<0.01 between the indicated comparison groups is plotted.

The relative position of amino acids within a CDR3β will vary with the total length of the CDR3 loop. We therefore performed more extensive analyses using CDR3 sequences segregated by length (Suppl. Fig. 2a–h). This verified the results with pooled sequences (Fig. 7), and delineated additional length-constrained variations. For example, significantly increased E incorporation at position 4 in CNS Foxp3− TCR was seen in 8, 9, 12, and 13 amino acid long CDR3β, and trended higher in 11 amino acid CDR3β, but was not evident in 10 or 14 amino acid long sequences. Therefore, amino acid composition in Treg or Tconv and splenic or CNS CDR3β varies in a CDR3 length dependent manner.

The propensity to differentially incorporate CDR3β amino acids was not uniform across population cohorts. In the analyses of fixed length CDR3β (Suppl. Fig. 2; a total of 700 positions/amino acids compared for the 4 population groups) only a single significant difference was observed between a splenic Foxp3+ and splenic Foxp3− population, a variation in the use of N at position 8 in 12 amino acid long CDR3 (Suppl. Fig. 2e). In contrast, 41 significant differences were seen when comparing CNS Foxp3+ and CNS Foxp3− CDR3β sequences (Suppl. Fig. 2 and Fig. 7d). Intermediate numbers of differences were observed when CNS populations were compared with splenic populations. Therefore, specific amino acids preferentially incorporate at specific positions. These amino acid preferences are particularly prevalent in the CDR3β of Foxp3+ and Foxp3− CNS infiltrating T cells. Interestingly, some sequence variations, such as the use of E at position 4, distinguish the CNS Foxp3+ or Foxp3− cohorts from each other, whereas others, such as the G at position 6, more broadly distinguish CNS infiltrating cells from splenic T lymphocytes.

Discussion

Information on the repertoires of T cells responding during autoimmunity is limited. Using MOG-EAE as a model system, we evaluated the Treg and Tconv repertoires both in the CNS, the site of autoimmune inflammation, and in the periphery. To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive repertoire evaluation that has been performed in an autoimmune model, with >160,000 sequences assessed. The depth of the sequencing was reflected in the low ϕmax values acquired for individual samples. Our results provide new insights into the nature of the Treg and Tconv responses during EAE.

Treg are critical modulators of autoimmune inflammation in EAE (39), and IL-10 is essential for their effectiveness. Blockade of IL-10 or IL-10 deficiency in either nTreg or iTreg inhibits their regulatory capacity in EAE (4, 6, 40). Only a small subset of Treg express IL-10 after direct isolation from peripheral lymphoid organs, but IL-10+ Treg are highly enriched within the CNS of mice with MOG-EAE and appear to comprise the primary T cell source of this cytokine (23, 24). Other Treg cytokines, particularly TGF-β, and functions may further support IL-10 induced disease suppression (41).

In actively induced EAE, T cells are stimulated in the periphery, then migrate to the CNS where they are restimulated with antigen and further expand (42). Increasing numbers of Foxp3+ Treg are observed as disease progresses (23). One possibility is that the initial T cell response is comprised predominantly of effector T cells, and some of these convert into Treg which then form a protective response. Alternatively, Treg and Teff may arise from different pre-immune populations and the kinetics of their expansion may differ. Indeed, one study demonstrated a proliferative burst among TRBV13+ Treg selectively in the CNS of mice with MOG-EAE (29).

Importantly, we failed to identify substantial interconversion between Treg and Tconv in diseased mice. The MH indices of Treg and Tconv in the CNS or compared between the CNS and spleen were close to zero. This did not result from different Jβ use in Treg and Tconv as there was no difference in Jβ representation between any of the TCR cohorts. Further, considering that small amounts of cross-contamination may occur with flow cytometric sorting, even the limited intersection between Treg and Tconv must be considered an overestimate of the true level of overlap.

In contrast to the CNS, a low but significantly increased overlap between Treg and Tconv was apparent in the spleen. Prior repertoire studies of healthy mice have shown similar low degrees of concordance between splenic Treg and Tconv repertoires (33, 35, 43). Why the Treg and Tconv repertoires are more polarized in the CNS than the spleen is unclear. One possibility is that shared TCR sequences are expressed by a distinct subset of cells more prone to interconversion, and these cells are relatively unimportant for the EAE response. The T cells recognizing CNS antigens may consist of a repertoire segment in which the Foxp3 expression pattern is more durable. For instance, T cell clones that recognize antigens presented by the mucosal immune system, where abundant tolerogenic APCs can promote iTreg induction, may have increased representation among overlapping sequences. Indeed, increased adaptive Treg generation is seen when Foxp3− T cells are transferred into lymphopenic compared with wild type hosts (18), a situation also associated with the activation of gut-specific T lymphocytes (8).

As MOG-specific T cells concentrate in the CNS during EAE (24), high frequency sequences should have an increased association with T cells engaged in the autoimmune response. As with the total T cell repertoires, the high frequency repertoires showed a greater intersection between Foxp3 homologous than heterologous cells in the CNS and spleen. Therefore, different analyses of the TCR repertoire in MOG-EAE lead to the same conclusion, that the Treg and Tconv repertoires are largely distinct and interconversion between Foxp3+ Treg and Tconv does not play a prominent role in EAE immunopathology.

Prior studies of Treg and Tconv TCR repertoires have not identified discriminatory structural properties with one exception. We previously showed in an analysis TRBV13-2+TRBJ2-7+ TCR of mice bearing a fixed TCRα an increase in CDR3β negative charge in CNS infiltrating Tconv relative to Treg (26). Notably, a similar charge bias was observed in wild type mice here. The MOG35–55 epitope possesses 3 R residues, two of which are anticipated to lie in the MHC binding groove with their guanidinium moieties pointing toward the TCR (44). Though speculative, it is possible that differential recognition of these basic residues by complementary acidic residues in the TCR is at least partially responsible for this increased negative charge.

This possibility is supported by our identification of specific amino acid preferences at discrete locations within the CDR3β. One particularly prominent preference was the increased use of an acidic residue, E, at position 4 (5th residue from the conserved CDR3 C) of CNS Tconv CDR3β. This residue falls at the site of V-D joining. A D at this location would be predicted for TRBV13-2+ TCR in the absence of N-region additions or deletions, and is indeed the most common residue present (Fig. 7a). However, minimal substitutions may lead to an E. It is intriguing that in a prior analysis by us of 18 TRBV13-2+TRBJ2-7+ MOG35–55-specific TCR with a fixed TCRα, 11 Tconv TCR and 7 Treg TCR, D or E residues were uniformly present at the same location only in Tconv receptors (26). These results suggest that an acidic residue in Tconv at position 4 is associated with and potentially important for Teff responsiveness.

Another preference was for a G at position 6. Though G was the most common residue for all TCR studied at the site, its use was equivalently increased in the CNS infiltrating Tconv and Treg populations. Interestingly, 16/18 of the MOG-specific TCR with a fixed TCRα mentioned above also bore a G at this location, associating use of this residue with disease. Multiple additional significant differences in amino acid usage were evident when comparing populations. Of relevance, only a single difference was observed when comparing the splenic Treg and Tconv TCR, whereas larger numbers segregated splenic and CNS populations or CNS Treg and Tconv. The consistent observation of amino acid preferences across individual experiments indicates that sequence preferences among CNS TCR are relevant to the EAE response. In contrast, the absence of sequence preferences when comparing splenic Tconv and Treg repertoires suggests that, although their repertoires are distinct, their TCR are derived from a more random pool with an amino acid composition that lacks any specific imprint.

Theoretically, >106 unique TRBV13-2+ sequences can form through V-D-J recombination. The presence of public sequences is therefore surprising, though has been observed in numerous other immune responses and likely reflects preferential products of V-D-J recombination that survive repertoire restrictions associated with thymic selection (45). We were able to validate our data set compared with smaller numbers of TRBV13-2+ TCR that have been described in the literature. All of the previously described public sequences and half of private TCR were identified, implying that a greater proportion of the autoimmune repertoire is public than previously appreciated. Importantly, phylogenetic analysis clustered some of the public CNS sequences into groups with similar motifs that segregated Treg and Tconv sequences. This implies that these TCR are not a result of chance associations with disease in multiple animals, and that the TCR structural motifs, and presumably affiliated ligand recognition properties, are associated with regulatory or conventional lineage identification. The fact that these TCR groups were observed in multiple mice suggests that they likely associate with different TCRα and emphasizes the importance of the TCRβ chain in MOG-EAE.

Our analyses studied an unbiased repertoire, and did not use MOG-tetramers to preselect antigen-specific cells. There were several reasons for this choice. First, a prior study of ours analyzing TCR repertoires in MOG-EAE in mice with a fixed TCRα found that 100% of high frequency TRBV13-2+ Teff TCR in the CNS were MOG-specific, but this was true for only 50% of high frequency Treg TCR. The non-specific yet high frequency Treg may have been bystanders. However, it would seem more likely that such non-specific Treg were disease-relevant but not MOG-specific. TCR specific for alternative antigens would be excluded by studying a tetramer-selected repertoire. Second, our assessment of MOG tetramer has identified limitations in its use (R. Alli, T. Geiger, data not published). We observed that the tetramer does not stain the MOG-specific 2D2 transgenic TCR, a finding replicated by the NIH tetramer core facility (www.yerkes.emory.edu). We also tested this tetramer against 2 different TRBV13-2+ TCR we previously isolated, 1MOG9 and 1MOG244.2 (38), and failed to obtain staining with either. It therefore seems likely that MOG-tetramer only stains a subset of MOG-specific TCR, perhaps due to avidity limitations or the presence of multiple peptide binding registers, and the proportion of reactive TCR is not established. Further, we cannot determine whether interconversion of T cells between Foxp3+ and Foxp3− subsets alters tetramer recognition of individual TCR, which if present would skew analyses and interpretations. Finally, a study using MOG-tetramer found that fewer than 10% of Treg bind tetramer at disease peak (24). Considering the small number of CNS-infiltrating Treg that can be isolated by flow cytometric sorting, obtaining optimal cell numbers form CNS tetramer sorted populations for sequencing would represent significant challenges. Nevertheless, the data we have obtained can be used as a basis for future studies with cell populations sorted based on specificity.

The use of high throughput sequencing to assess the TCR repertoire in EAE has the potential to assist in resolving additional features of the T cell response during autoimmunity. For example, Krishnamoorthy and colleagues have demonstrated that a subset of T cells specific for MOG35–55 are cross reactive for a second neuroantigen, NF-M18–30 (46). A high resolution assessment of the dynamics of NF-M response development during EAE and the repertoire correspondence between MOG and NF-M-specific T cells is possible using this approach and would help define the relationship between T cells specific for the inducing antigen, MOG, and NF-M.

In summary, large scale sequencing of the TRBV13-2 repertoire in EAE indicates that Treg and Tconv T cells form discrete populations with highly distinct repertoires. Interconversion between Treg and Tconv in either direction is not substantive and does not appear to play a significant role in forming the T cell response. We further demonstrate that high resolution repertoire analysis is able to define primary structural features of CDR3 that distinguish Treg from Tconv and CNS infiltrating from splenic T cell repertoires in mice with active disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Richard Cross, Greig Lennon, Stephanie Morgan and the Immunology Core Flow Cytometry facility for assistance with flow cytometric sorting, and Caroline Obert and Dana Roeber for assistance with Illumina sequencing.

Supported by NIH grant 2R01 AI056153 (to TLG and CC) and by the American Lebanese Syrian Affiliated Charities/St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (to all authors).

Reference List

- 1.Fontenot JD, Rudensky AY. A well adapted regulatory contrivance: regulatory T cell development and the forkhead family transcription factor Foxp3. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:331–337. doi: 10.1038/ni1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang Q, Bluestone JA. The Foxp3+ regulatory T cell: a jack of all trades, master of regulation. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:239–244. doi: 10.1038/ni1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vignali DA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:523–532. doi: 10.1038/nri2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selvaraj RK, Geiger TL. Mitigation of Experimental Allergic Encephalomyelitis by TGF-{beta} Induced Foxp3+ Regulatory T Lymphocytes through the Induction of Anergy and Infectious Tolerance. J Immunol. 2008;180:2830–2838. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mekala DJ, Alli RS, Geiger TL. IL-10-dependent infectious tolerance after the treatment of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis with redirected CD4+CD25+ T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:11817–11822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505445102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X, Koldzic DN, Izikson L, Reddy J, Nazareno RF, Sakaguchi S, Kuchroo VK, Weiner HL. IL-10 is involved in the suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells. Int. Immunol. 2004;16:249–256. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyara M, Sakaguchi S. Natural regulatory T cells: mechanisms of suppression. Trends Mol. Med. 2007;13:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powrie F. Immune regulation in the intestine: a balancing act between effector and regulatory T cell responses. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1029:132–141. doi: 10.1196/annals.1309.030. 132–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curotto de Lafaille MA, Lafaille JJ. Natural and adaptive foxp3+ regulatory T cells: more of the same or a division of labor? Immunity. 2009;30:626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selvaraj RK, Geiger TL. A kinetic and dynamic analysis of Foxp3 induced in T cells by TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2007;178:7667–7677. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng SG, Meng L, Wang JH, Watanabe M, Barr ML, Cramer DV, Gray JD, Horwitz DA. Transfer of regulatory T cells generated ex vivo modifies graft rejection through induction of tolerogenic CD4+CD25+ cells in the recipient. Int. Immunol. 2006;18:279–289. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huter EN, Stummvoll GH, Dipaolo RJ, Glass DD, Shevach EM. Cutting edge: antigen-specific TGF beta-induced regulatory T cells suppress Th17-mediated autoimmune disease. J. Immunol. 2008;181:8209–8213. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang XO, Nurieva R, Martinez GJ, Kang HS, Chung Y, Pappu BP, Shah B, Chang SH, Schluns KS, Watowich SS, et al. Molecular antagonism and plasticity of regulatory and inflammatory T cell programs. Immunity. 2008;29:44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuji M, Komatsu N, Kawamoto S, Suzuki K, Kanagawa O, Honjo T, Hori S, Fagarasan S. Preferential generation of follicular B helper T cells from Foxp3+ T cells in gut Peyer's patches. Science. 2009;323:1488–1492. doi: 10.1126/science.1169152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Komatsu N, Mariotti-Ferrandiz ME, Wang Y, Malissen B, Waldmann H, Hori S. Heterogeneity of natural Foxp3+ T cells: a committed regulatory T-cell lineage and an uncommitted minor population retaining plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:1903–1908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811556106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou X, Bailey-Bucktrout S, Jeker LT, Bluestone JA. Plasticity of CD4(+) FoxP3(+) T cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2009;21:281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang S, Alard P, Zhao Y, Parnell S, Clark SL, Kosiewicz MM. Conversion of CD4+CD25- cells into CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in vivo requires B7 costimulation, but not the thymus. J Exp. Med. 2005;201:127–137. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lathrop SK, Santacruz NA, Pham D, Luo J, Hsieh CS. Antigen-specific peripheral shaping of the natural regulatory T cell population. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:3105–3117. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gavin MA, Rasmussen JP, Fontenot JD, Vasta V, Manganiello VC, Beavo JA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3-dependent programme of regulatory T-cell differentiation. Nature. 2007;445:771–775. doi: 10.1038/nature05543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wan YY, Flavell RA. Regulatory T-cell functions are subverted and converted owing to attenuated Foxp3 expression. Nature. 2007;445:766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature05479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y, Teige I, Birnir B, Issazadeh-Navikas S. Neuron-mediated generation of regulatory T cells from encephalitogenic T cells suppresses EAE. Nat. Med. 2006;12:518–525. doi: 10.1038/nm1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luth S, Huber S, Schramm C, Buch T, Zander S, Stadelmann C, Bruck W, Wraith DC, Herkel J, Lohse AW. Ectopic expression of neural autoantigen in mouse liver suppresses experimental autoimmune neuroinflammation by inducing antigen-specific Tregs. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3403–3410. doi: 10.1172/JCI32132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGeachy MJ, Stephens LA, Anderton SM. Natural recovery and protection from autoimmune encephalomyelitis: contribution of CD4+CD25+ regulatory cells within the central nervous system. J Immunol. 2005;175:3025–3032. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korn T, Reddy J, Gao W, Bettelli E, Awasthi A, Petersen TR, Backstrom BT, Sobel RA, Wucherpfennig KW, Strom TB, et al. Myelin-specific regulatory T cells accumulate in the CNS but fail to control autoimmune inflammation. Nat. Med. 2007;13:423–431. doi: 10.1038/nm1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong J, Mathis D, Benoist C. TCR-based lineage tracing: no evidence for conversion of conventional into regulatory T cells in response to a natural self-antigen in pancreatic islets. J Exp. Med. 2007;204:2039–2045. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Nguyen P, Liu W, Cheng C, Steeves M, Obenauer JC, Ma J, Geiger TL. T cell receptor CDR3 sequence but not recognition characteristics distinguish autoreactive effector and Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2009;31:909–920. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendel I, Kerlero dR, Ben Nun A. A myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide induces typical chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in H-2b mice: fine specificity and T cell receptor V beta expression of encephalitogenic T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 1995;25:1951–1959. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendel Kerlero de RN, Ben-Nun A. Delineation of the minimal encephalitogenic epitope within the immunodominant region of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein: diverse V beta gene usage by T cells recognizing the core epitope encephalitogenic for T cell receptor V beta b and T cell receptor V beta a H-2b mice. Eur. J Immunol. 1996;26:2470–2479. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'connor RA, Malpass KH, Anderton SM. The inflamed central nervous system drives the activation and rapid proliferation of foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:958–966. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Williams LM, Dooley JL, Farr AG, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity. 2005;22:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsieh CS, Zheng Y, Liang Y, Fontenot JD, Rudensky AY. An intersection between the self-reactive regulatory and nonregulatory T cell receptor repertoires. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:401–410. doi: 10.1038/ni1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong J, Obst R, Correia-Neves M, Losyev G, Mathis D, Benoist C. Adaptation of TCR repertoires to self-peptides in regulatory and nonregulatory CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:7032–7041. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsieh CS, Liang Y, Tyznik AJ, Self SG, Liggitt D, Rudensky AY. Recognition of the peripheral self by naturally arising CD25+ CD4+ T cell receptors. Immunity. 2004;21:267–277. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pacholczyk R, Ignatowicz H, Kraj P, Ignatowicz L. Origin and T cell receptor diversity of Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ T cells. Immunity. 2006;25:249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fazilleau N, Delarasse C, Sweenie CH, Anderton SM, Fillatreau S, Lemonnier FA, Pham-Dinh D, Kanellopoulos JM. Persistence of autoreactive myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)-specific T cell repertoires in MOG-expressing mice. Eur. J Immunol. 2006;36:533–543. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alli R, Nguyen P, Geiger TL. Retrogenic modeling of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis associates T cell frequency but not TCR functional affinity with pathogenicity. J Immunol. 2008;181:136–145. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'connor RA, Anderton SM. Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in the control of experimental CNS autoimmune disease. J. Neuroimmunol. 2008;193:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mekala DJ, Alli RS, Geiger TL. IL-10-dependent suppression of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by Th2-differentiated, anti-TCR redirected T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 2005;174:3789–3797. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang X, Reddy J, Ochi H, Frenkel D, Kuchroo VK, Weiner HL. Recovery from experimental allergic encephalomyelitis is TGF-beta dependent and associated with increases in CD4+LAP+ and CD4+CD25+ T cells. Int. Immunol. 2006;18:495–503. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bailey SL, Schreiner B, McMahon EJ, Miller SD. CNS myeloid DCs presenting endogenous myelin peptides 'preferentially' polarize CD4+ T(H)-17 cells in relapsing EAE. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:172–180. doi: 10.1038/ni1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pacholczyk R, Ignatowicz H, Kraj P, Ignatowicz L. Origin and T cell receptor diversity of Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ T cells. Immunity. 2006;25:249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ben-Nun A, Kerlero de RN, Kaushansky N, Eisenstein M, Cohen L, Kaye JF, Mendel I. Anatomy of T cell autoimmunity to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG): prime role of MOG44F in selection and control of MOG-reactive T cells in H-2b mice. Eur. J Immunol. 2006;36:478–493. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Venturi V, Price DA, Douek DC, Davenport MP. The molecular basis for public T-cell responses? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:231–238. doi: 10.1038/nri2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krishnamoorthy G, Saxena A, Mars LT, Domingues HS, Mentele R, Ben-Nun A, Lassmann H, Dornmair K, Kurschus FC, Liblau RS, et al. Myelin-specific T cells also recognize neuronal autoantigen in a transgenic mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Med. 2009;15:626–632. doi: 10.1038/nm.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.