Abstract

Summary: Multi-netclust is a simple tool that allows users to extract connected clusters of data represented by different networks given in the form of matrices. The tool uses user-defined threshold values to combine the matrices, and uses a straightforward, memory-efficient graph algorithm to find clusters that are connected in all or in either of the networks. The tool is written in C/C++ and is available either as a form-based or as a command-line-based program running on Linux platforms. The algorithm is fast, processing a network of > 106 nodes and 108 edges takes only a few minutes on an ordinary computer.

Availability: http://www.bioinformatics.nl/netclust/

Contact: jack.leunissen@wur.nl

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

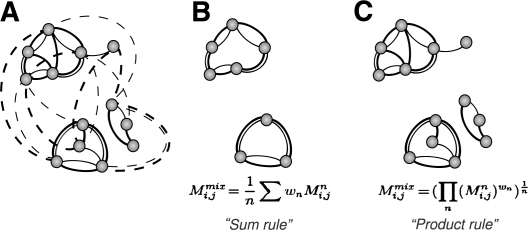

Finding tightly connected clusters in large datasets is a frequent task in many areas of bioinformatics such as the analysis of protein similarity networks, microarray or protein–protein interaction data. Classical clustering algorithms have difficulties in handling large datasets used in bioinformatics owing to high demands on computer resources. Fast heuristic algorithms have been developed for specific tasks, e.g. BLASTClust (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/blast/documents/blastclust.html) from the NCBI–BLAST package (Altschul et al., 1990), Tribe-MCL (Enright et al., 2002) or the CD-HIT (Li and Godzik, 2006) can delineate protein or gene families in a large network of sequence similarities (e.g. BLAST E-values). However, there are no apparent tools that could efficiently handle large multiple networks, such as those necessary to group proteins using more than one similarity criterion (e.g. based on sequence, structure or function) (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

The principle of Multi-netclust is illustrated on a two-parameter network. Thick and thin edges correspond to distinct similarity data (A). Dotted lines denote edges that are below the respective threshold, and hence can be omitted from the networks. Two different aggregation rules are implemented: the weighted arithmetic averaging (‘sum rule’) gives clusters that are connected within either of the two networks (B); the weighted geometric averaging (‘product rule’) gives clusters that are connected within both networks (C). Mij denotes the value assigned to the edges, w is the weighting factor (‘alpha’) of the two matrices (hence n = 2) and Mmix refers to the aggregated matrix.

We developed an efficient, semi-supervised tool that takes the users’ empirical knowledge of cutoff values into account (below which interactions or similarities can be neglected) to combine multiple data networks using an averaging or kernel fusion method (Kittler et al., 1998). The resulting combined network can then be queried for connected components (clusters) using an efficient implementation of the union-find algorithm (Tarjan, 1975). The clusters correspond to groups of nodes that are connected either by any or by all of the constituent networks, depending on the aggregation rule used (Fig. 1B and C, respectively). To adapt this method to large heterogeneous datasets, we combined the thresholding, aggregation as well as the connected component search into a single, memory- and time-efficient tool, Multi-netclust. Multi-netclust is not a new clustering method but an optimized implementation of existing graph algorithms suitable for handling large networks of > 106 nodes and 108 edges.

2 MULTI-NETCLUST INPUT AND OUTPUT

Multi-netclust uses external memory rather than the in-core approach (Chiang, 1995) for matrix manipulations so that the size of the datasets is not a limiting factor. The input to Multi-netclust are networks given in sparse matrix format, as well as the aggregation rule, ‘alpha’ weighting factor, and similarity (or distance) cutoff value(s) associated with a processing step(s). Generally, the product rule results in more reliable connections confirmed by multiple data sources, whereas the sum rule expands the network with new (not necessarily reliable) connections. Setting the ‘alpha’ value for each matrix provides means, e.g. to weight the reliability of different data sources or to decide which dataset is more likely to contribute with new (additional) information. A permissive cutoff value usually results in a few large clusters, while a strict cutoff value tend to produce many small (singleton) clusters. The data can be entered either via a CGI interface, or from the command line. The output of Multi-netclust is a list of the connected clusters given in a structured text format.

Multi-netclust is written in the C/C++ language, and the CGI interface is a Perl script. The source code, sample data, explanations and benchmark results are available on the website http://www.bioinformatics.nl/netclust/. There is also a web-based application suitable to run smaller test-sets.

3 PERFORMANCE

The run-time of Multi-netclust subsumes: (i) the time needed for reading-in the data, thresholding and aggregation (>99.9%); and (ii) finding the connected components and writing the results (<0.1%). A benchmark dataset of 1357 proteins, taken from the Protein Classification Benchmark database (Sonego et al., 2007) was used to combine sequence similarities calculated by the BLAST and Smith–Waterman (Smith and Waterman, 1981) algorithms, and DALI 3D structure similarities (Holm and Sander, 1995). The analysis took 4 s on a 2 GHz processor, the influence of parameter settings on the purity of connected clusters is apparent from the results (Table 1). An interesting example is the immunoglobulin superfamily (SCOP b.1.1), which has 125 members in the benchmark dataset. Using DALI alone, the b.1.1 proteins clustered together with the ‘E set domains’ (SCOP b.1.18), grouping proteins related to immunoglobulin and/or fibronectin Type III superfamilies. Using BLAST alone, the b.1.1. proteins clustered together with a number of other superfamilies. Surprisingly, the combination of both DALI and BLAST datasets made 94% of the group b.1.1 cluster correctly.

Table 1.

Protein classification results obtained for the individual and combined similarity networks

| Dataset | Correct | Incorrect | Singletons |

|---|---|---|---|

| SW × DALI1 (251) | 910 | 0 | 447 |

| BLAST (0.1) × DALI2 (0.4) | 888 | 0 | 469 |

| BLAST (0.4) + DALI2 (0.4) | 803 | 469 | 85 |

| SW (251) | 316 | 0 | 1041 |

| DALI1 (251) | 56 | 1266 | 35 |

| DALI2 (0.4) | 790 | 475 | 92 |

| BLAST (0.4) | 36 | 0 | 1321 |

| BLAST (0.1) | 66 | 1101 | 190 |

Numbers in parentheses denote the threshold used. Symbols ‘×’ and ‘+’ refer to the product and sum aggregation rules, respectively. The results were obtained for ‘alpha’ weighting factor 0.5.

DALI1, matrix of raw scores; DALI2, matrix of diagonally normalized scores; correct, proteins connected only to members of the same SCOP superfamily; incorrect, proteins connected to members of other SCOP superfamilies.

The external memory-based, connected component search algorithm is fast and memory-efficient compared to single-linkage-based clustering methods and in-memory graph algorithms used for similar purposes within the bioinformatics community (see Supplementary Material). The strength of Multi-netclust becomes more apparent when we deal with large datasets that cannot be handled with other algorithms. For example, a network of 2 713 908 nodes and 781 328 458 edges took <5 min on an ordinary computer. Of the other algorithms tested (see case studies on the website), only BLASTClust was able to handle a dataset of similar size; however, its use is limited to BLAST similarity networks (and at greater expense of CPU time and memory required), whereas Multi-netclust is generally applicable. To conclude, Multi-netclust is an efficient tool that can aid exploratory analyzes of large biological networks using an ordinary computer. Specifically, the potential applications include any task where network data of heterogeneous sources, such as sequence and structure similarities, gene expression or protein–protein interaction data, are to be combined together, resulting in new and/or improved biologically relevant predictions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Pieter van Beek (SARA Computing and Networking Services) for help in providing additional BLAST data, Anand Gavai for preparing binaries for Mac OS X, Stijn van Dongen for the help with the MCL utilities and the NBIC initiative for using the Dutch Life Science Grid platform.

Funding: Graduate School Experimental Plant Sciences (to A.K.); BioAssist programme of the Netherlands Bioinformatics Centre (to H.N.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Altschul SF, et al. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang YJ, et al. Proceedings of the 6th Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (SODA'95). San Francisco, CA, USA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics; 1995. External-Memory Graph Algorithms; pp. 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Enright AJ, et al. An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1575–1584. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, Sander C. Dali: a network tool for protein structure comparison. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995;20:478–480. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittler J, et al. On combining classifiers. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1998;20:226–239. [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonego P, et al. A Protein Classification Benchmark collection for machine learning. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D232–D236. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TF, Waterman MS. Identification of common molecular subsequences. J. Mol. Biol. 1981;141:195–197. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarjan RE. Efficiency of a Good But Not Linear Set Union Algorithm. J. ACM. 1975;22:215–225. [Google Scholar]