Abstract

Motivation: Organic enzyme cofactors are involved in many enzyme reactions. Therefore, the analysis of cofactors is crucial to gain a better understanding of enzyme catalysis. To aid this, we have created the CoFactor database.

Results: CoFactor provides a web interface to access hand-curated data extracted from the literature on organic enzyme cofactors in biocatalysis, as well as automatically collected information. CoFactor includes information on the conformational and solvent accessibility variation of the enzyme-bound cofactors, as well as mechanistic and structural information about the hosting enzymes.

Availability: The database is publicly available and can be accessed at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/databases/CoFactor

Contact: julia.fischer@ebi.ac.uk

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Enzymes are proteins that catalyze the repertoire of chemical reactions found in nature, and as such are vitally important molecules. They are generally composed of the 20 common amino acid residues, but many also require small molecules in addition for the catalysis to occur. In some cases, these molecules are involved in regulation or in ensuring the correct folding remote from the active site. However, many are termed cofactors, as they are required in the active site and are directly involved in catalysis. These cofactors may be either metal ions, whose involvement in catalysis we handle in Metal-MACiE (Andreini et al., 2009), or small organic molecules, which are described here. In both cases, these cofactors extend and enhance the basic catalytic toolkit of enzymes.

To date, there has been little collation of information on organic cofactors and their functions outside of the primary literature. CoFactor has been designed to remedy this, as MACiE (Holliday et al., 2007) and Metal-MACiE were designed to collate data on enzyme mechanisms and metal ions in catalysis, respectively.

2 DATA CONTENT

The CoFactor database contains 27 entries for organic enzyme cofactors (see Supplementary Table S1). On the index page, the user can choose which cofactor entry to view. The left-hand navigation contains links to all the pages described, as well as to the home page, a glossary page, a contact form and a database statistics page. For each cofactor, the web site provides:

Overview page—hand-curated information, mostly from primary literature. This includes general information about the molecule, its chemical properties, and about pathways where appropriate.

Mechanism (if available in MACiE)—in the standard curly arrow representation of organic chemistry and an optional textual description.

Enzymes and domains—enzyme information is integrated with associated 3D structures from PDBe, PDBsum, (Laskowski, 2009), CATH domains (Orengo et al., 1997), MACiE enzyme mechanism, proteins that have been assigned this E.C. number according to Uniprot (Consortium, 2008), as well as a reference that documents the provenance of the information.

- Enzymes that use this cofactor—including visual representations of the cofactor's distribution over enzyme reaction space and its chemical profile, based on the enzyme classification (NC-IUBMB and Webb, 1992).

- Enzymes that synthesize this cofactor.

- Enzymes that recycle this cofactor (if known and applicable).

- Domains that bind this cofactor, taken from PROCOGNATE (Bashton et al., 2006).

- Compound—names and identifiers of the same molecule in ChEBI (Degtyarenko et al., 2008), KEGG COMPOUND (Kanehisa and Goto, 2000), PDBeChem (Boutselakis et al., 2003) and PROCOGNATE (Bashton et al., 2006). For each PDB HET code, the web site provides:

- Conformation of the cofactor—shows the superimposed molecules, as described in Section 3, in a three-dimensional molecule viewer.

- Solvent accessibility—displays the average atomic solvent accessibility and its standard deviation for each HET code (PDB identifier for non-amino acid molecules) associated with this cofactor.

3 METHODS

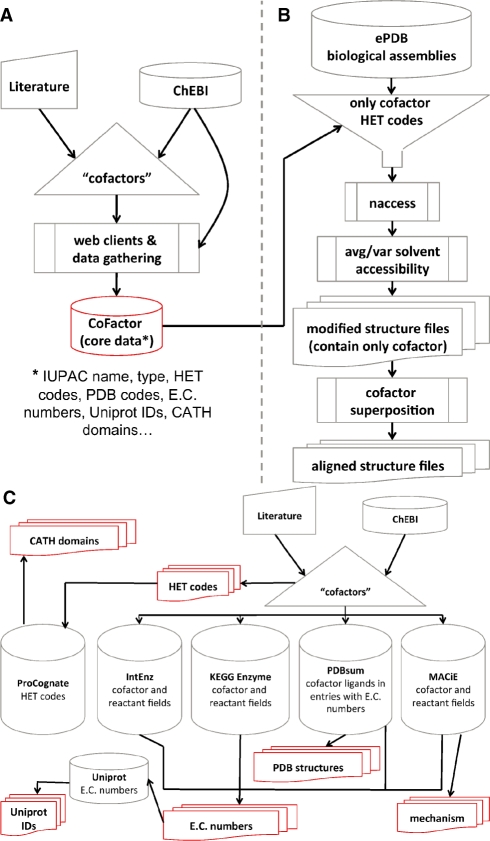

The data collection process used to populate the database is summarized in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of data collection for the CoFactor database. CoFactor core data is shown in red. (A) Overview. (B) pipeline for solvent accessibility and 3D superposition calculations. (C) detailed view of the automated data collection.

All X-ray and NMR structures in the PDBe biological assemblies database (Boutselakis et al., 2003), which contain a HET group assigned to a cofactor, have been used for the superposition and solvent accessibility calculations. All instances of one cofactor HET group have been superimposed on a rigid part of the molecule. NACCESS (Hubbard and Thornton, 1993) was applied to compute the solvent accessibility of each atom a in each cofactor twice: first for the biological assembly (SAbiolAssembly(a)) and second for the cofactor alone SAcofactorAlone(a). The relative solvent accessibility of each atom a RSA(a) has been calculated as shown in below.

| (1) |

The mechanisms are based on all the information on a cofactor molecule in MACiE. All mechanisms have been visually inspected and all substrates and products have been abstracted to be reduced to the essential bonds that are involved in the reaction mechanism catalyzed by this cofactor.

4 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The CoFactor database provides an overview for each organic enzyme cofactor. It integrates information on the organic compounds with protein structures, domains, sequences, enzyme reactions and mechanisms. These data can be used to learn about the tasks of cofactors in biocatalysis and an analysis of cofactor properties, structure and function is in progress (Fischer, J.D. et al., submitted for publication). Most of the cofactors have been known for many years, with very few recent discoveries. Therefore, we do not expect that this data resource will require major changes in the future.

Funding: European Molecular Biology Laboratory.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Andreini C, et al. Metal-MACiE: a database of metals involved in biological catalysis. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2088–2089. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashton M, et al. Cognate ligand domain mapping for enzymes. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;364:836–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutselakis H, et al. E-MSD: the European Bioinformatics Institute Macromolecular Structure Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:458–462. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degtyarenko K, et al. ChEBI: a database and ontology for chemical entities of biological interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D344–D350. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday GL, et al. MACiE (mechanism, annotation and classification in enzymes): novel tools for searching catalytic mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D515–D520. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard SJ, Thornton JM. NACCESS. Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. University College London; 1993. Available at http://www.bioinf.manchester.ac.uk/naccess/(last accessed date July 28, 2008) [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA. Pdbsum new things. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D355–D359. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NC-IUBMB , Webb EC. Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (NC-IUBMB). Enzyme nomenclature. Recommendations 1992. San Diego, California: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Orengo CA, et al. CATH–a hierarchic classification of protein domain structures. Structure. 1997;5:1093–1108. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uniprot Consortium. The universal protein resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D190–D195. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.