Abstract

Purpose

To determine if fibromyalgia or fibromyalgianess is increased in SLE compared with non-SLE patients, whether fibromyalgia or fibromyalgianess (the tendency to respond to illness and psychosocial stress with fatigue, widespread pain, general increase in symptoms and similar factors ) biases the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Activity Questionnaire (SLAQ), and to determine if the SLAQ is overly sensitive to fibromyalgia symptoms.

Method

We developed a 16-item SLE symptom scale (SLESS) modeled on the SLAQ and used that scale to investigate the relation between SLE symptoms and fibromyalgianess in 23,321 rheumatic disease patients. Fibromyalgia was diagnosed by survey fibromyalgia criteria and fibromyalgianess was measured using the Symptom Intensity Scale (SI). As comparison groups, we combined patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and non-inflammatory rheumatic disorders into an “arthritis” group and also utilized a physician-diagnosed group of fibromyalgia patients.

Results

Fibromyalgia was identified in 22.1% of SLE and 17.0% of those with arthritis. The SI scale was minimally increased in SLE. The correlation between SLAQ and SLESS was 0.738. SLESS/SLAQ scale items: Raynaud’s, rash, fever, easy bruising and hair loss were significantly more associated with SLE than fibromyalgia, while the reverse was true for headache, abdominal pain, paresthesias/stroke, fatigue, cognitive problems and muscle pain or weakness. There was no evidence of a disproportionate symptom reporting associated with fibromyalgianess. Self-reported SLE was associated with an increased prevalence of fibromyalgia when unconfirmed by physicians compared to SLE confirmed by physicians.

Conclusions

The prevalence of fibromyalgia in SLE is minimally increased compared with its prevalence in patients with arthritis. Fibromyalgianess does not bias the SLESS and should not bias SLE assessments, including the SLAQ.

Keywords: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Fibromyalgia, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Activity Questionnaire, SLAQ, SLAM

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can be difficult to diagnose with current criteria (1;2) when it is necessary to rely on “soft” findings or difficult to validate signs and symptoms, and it is often the case that a layer of uncertainty lies over SLE diagnosis in some patients . Similarly, assessing SLE activity can also be problematic. One particular problem relating both to diagnosis and activity is the presence of fibromyalgia, either as a separate confounding diagnosis or as a confounder of lupus activity. In particular, uncertainty arises because fatigue, aching and other somatic symptoms can be found in both SLE and fibromyalgia.

The issue of SLE and fibromyalgia has been approached by a number of investigators (3–9). Two approaches to the problem have included trying to distinguish persons with fibromyalgia from those with SLE and identifying persons with SLE who also have fibromyalgia. Implicit in these approaches is the assumption that fibromyalgia is, or can be treated as, a separate entity. As a separate entity fibromyalgia can “cause” or be responsible for some SLE symptoms. For example, under the distinct entity assumption a patient who has fibromyalgia may experience increased fatigue because of fibromyalgia.

Even though fibromyalgia is a diagnostic entity recognized by the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria (10) and may have value in clinical medicine, there are sufficient clinical and epidemiological data to show that fibromyalgia does not exist as a separate entity, but rather represents the end of a pain-distress spectrum (11–14). We have recently shown that the prevalence and intensity of fibromyalgia related symptoms –something that we call “fibromyalgianess” – may be thought of as a latent variable that exists as a continuum across all rheumatic diseases, and that it functions as a response to illness and illness distress (15–17). Fibromyalgianess is the tendency to respond to illness and psychosocial stress with fatigue, widespread pain, general increase in symptoms and similar factors (16), and can be measured on a continuous scale using the Symptom Intensity (SI) Scale. Measurement of fibromyalgianess with the SI scale increases the ability to assess fibromyalgia-like characteristics in SLE and avoids the dichotomizing problem created by fibromyalgia diagnosis and described by Altman and Royston who indicate that when dichotomizing continuous states “Individuals closeto but on opposite sides of the cut point are characterised asbeing very different rather than very similar (18).”

In this study we examined the relation between fibromyalgia diagnosis and fibromyalgianess and SLE in order to address three questions: Is fibromyalgia and fibromyalgianess increased in SLE? To what extent are SLE diagnostic and activity symptoms influenced by fibromyalgia and fibromyalgianess? Are SLE diagnosis and activity assessments biased by fibromyalgia or fibromyalgianess?

Methods

Patient population

We studied participants in the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases (NDB) longitudinal study of rheumatic disease outcomes. NDB participants are diagnosed by United States rheumatologists and are recruited from their practices. Patients are followed prospectively with semi-annual, detailed, 28-page questionnaires, as previously described (19;20). SLE patients were enrolled largely by rheumatologist referral, but also by self- referral. After enrollment of self-referred SLE patients, we sought to obtain each patient’s consent to verify the diagnosis with the patient’s physician. SLE patients with a non-verified or pending verification of diagnosis were excluded from the main study. Rheumatologists were the physicians who referred or confirmed the diagnosis in 96.3% of cases. However, we also determined the prevalence of fibromyalgia in diagnosis-verified SLE patients (N=834) as well as in all SLE enrolled patients in a separate analysis. All patients diagnosed as having SLE completed the common set of NDB assessments in addition to specific SLE assessments. Enrollment of patients into the NDB was begun in 1998 and was continued on an ongoing basis. When patients completed more than one semi-annual survey questionnaire, we selected the last survey questionnaire for analysis.

This report examined data from 23,231 adult rheumatic disease patients after excluding 221 with non-verified self-reported SLE. Of diagnoses, 834 had physician-verified SLE, 2,307 had fibromyalgia 16,884 had rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and 3,206 had a non-inflammatory rheumatic disorder that was not fibromyalgia.

To determine the prevalence of fibromyalgia in SLE we used fibromyalgia survey criteria (15;16;21). By these criteria, person with scores ≥ 8 on the Regional Pain Scale (RPS) (17) and ≥ 6 on the visual analog fatigue scale (22) are classified as having fibromyalgia. The RPS is a self-report count of non-articular regions (17;21). The Symptom Intensity (SI) scale measures fibromyalgianess. Derived from the fatigue and RPS scales, the SI scale combines these two measures in continuous form according to the following formula: (VAS fatigue + (RPS/2))/2 (16). This yields a scale with a 0 to 9.75 range. For the comparison of SLE symptoms in SLE and fibromyalgia patients, we used diagnoses of fibromyalgia supplied at the time patients enrolled into the NDB. Patients with fibromyalgia did not have a simultaneous diagnosis of SLE or a non-inflammatory rheumatic disorder.

In addition to the SI scale, 458 SLE patients participating in the NDB in January 2007 completed the Systemic Lupus Activity Questionnaire (SLAQ) (23). The SLAQ is a validated (24) 24-item questionnaire that reduces to 17 items for scoring and has a range of 0–44. In addition, the SLAQ contains a single item 0–10 rating scale for lupus activity and a rating scale for lupus flare (no flare, mild flare, moderate flare, severe flare). The SLAQ is a patient reported version of the physician-reported Systemic Lupus Activity Measure (SLAM) (25). However, the SLAQ is a new questionnaire and has only been reported on twice (23)(24).

To assess a similar lupus measure in non-SLE patients we constructed the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Symptom Scale (SLESS) based on symptoms occurring in the previous six month reported by patients on the NDB semi-annual questionnaire that was developed in 1998. Using scoring rules similar to those used for the SLAQ, we constructed a 16-item count of symptoms. We had 16 items rather than 17 because we did not have data on adenopathy. Additionally, data for the SLESS were dichotomous rather than scaled, and the SLESS time frame was six month instead of the 3 months used in the SLAQ. The range of values for the SLESS was 0–16. The items of the SLESS are shown in Table 1 and Figures 1 and 2. The specific question used to elicit responses was “During the past 6 months have you had any of the following symptoms? Then the checklist 56 symptoms were listed. In this scale the following items were endorsed by patients: mouth sores, headache; chest pain; shortness of breath; loss of appetite; pain or discomfort in upper abdomen (stomach); pain or cramps in lower abdomen (colon); joint pain; joint swelling; muscle pain; weakness of muscles; depression; seizures or convulsions; tiredness (fatigue); trouble thinking or remembering; hives or welts; rash; loss of hair; red, white and blue skin color changes in fingers on exposure to cold or with emotional upset; sun sensitivity (unusual skin reaction, not sunburn); fluid-filled blisters. Stroke information was obtained from a specific stroke question. Mouth sores, rash, and sun sensitivity (unusual skin reaction, not sunburn) were combined into a single variable, as were chest pain and dyspnea, stroke and paresthesias, hives or welts and fluid filled blisters, numbness/tingling/burning and stroke, depression and trouble thinking or remembering, muscle pain and weakness, joint swelling and joint pain, pain or discomfort in upper abdomen (stomach)and pain or cramps in lower abdomen (colon). The full questionnaire is available at http://www.arthritis-research.org/documents/Ph50RAFIB.pdf

Table 1.

Severity, SLE symptoms and fibromyalgia-related scales

| Variables | Fibromyalgia | SLE | RA + NIRD (Arthritis) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Participants | 2,397 | 834 | 20,096 |

| SLE symptom scale (SLESS) (0–16) | 7.3 (3.0) | 7.2 (3.7)* | 4.5 (3.0) |

| Symptom intensity (SI) Scale (0–9.75) | 5.8 2.3) | 4.0 (2.5)*† | 3.6 (2.3) |

| Regional pain scale (RPS) (0–19) | 10.7 (5.6) | 6.8 (5.6)*† | 5.6 (5.1) |

| Fatigue Scale (0–10) | 6.3 (2.7) | 4.6 (3.0)† | 4.5 (3.0) |

| Patient Global (0–10) | 5.0 (2.5) | 3.6 (2.6)† | 3.7 (2.5) |

NIRD: Non-inflammatory rheumatic disorders

P<0.05 compared with arthritis.

P<0.05 compared with fibromyalgia.

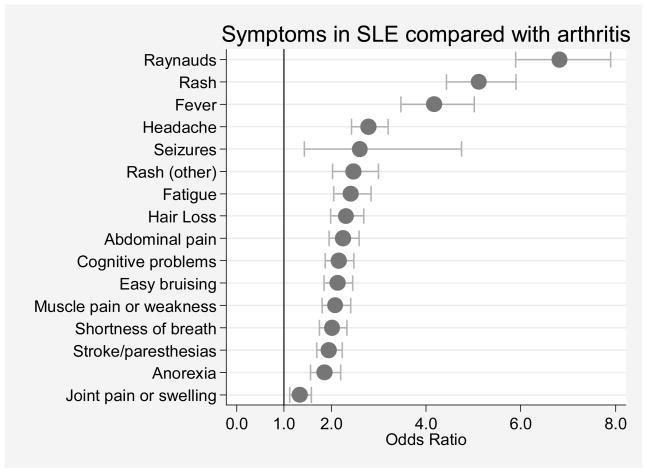

Figure 1.

SLE symptom scale (SLESS) items in 20,141 patients with arthritis compared with 961 with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis is defined as rheumatoid arthritis (N=16,910) or non-inflammatory rheumatic disorders (N=3,231). Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are represented by dots and their corresponding bracketed horizontal lines.

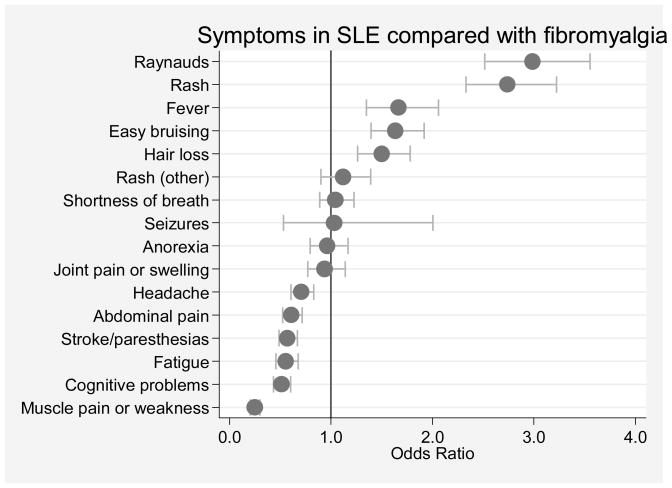

Figure 2.

SLE symptom scale items in 2,409 patients with fibromyalgia compared with 961 with systemic lupus erythematosus. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are represented by dots and their corresponding bracketed horizontal lines.

Statistical methods

Differences in group means for diagnostic groups were tested using linear regression (Table 1). Differences between groups for SLESS items were analyzed by logistic regression and reported on Figures 1 and 2 as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Data analysis included logistic regression in univariable and multivariable analyses as described in the results section. We also used fractional polynomial regression to test whether a non-linear model of the regression of SLESS on the SI scale was superior to a linear model. We combined the RA and NIRD into a single group, “arthritis” for most analyses, as results were similar in these groups. Data were analyzed using Stata (College Station, TX) version 10.0. Statistical significance was set at the 0.05 level, confidence intervals were established at 95%, and all tests were two-tailed.

Results

Demographic, severity and treatment characteristics

The mean (SD) age of the 458 SLE participants completing the SLAQ was 50.4 (12.3) years, and 95.3% were women. Current therapies included hydroxychloroquine (64.1%), prednisone (49.4%), methotrexate (12.3%), rituximab (0.8%), mycophenolate mofetil (11.8%), azathioprine (11.0%), cyclophosphamide (11.2%) and leflunomide (1.9%).

The mean composite SLAQ score and the single item SLAQ activity score was 12.1 (7.6) and 3.8 (2.8), respectively. A mild, moderate and severe SLE flare was reported by 34.1%, 22.0% and 9.1% during the preceding 3 months. Alpha reliability of SLAQ score items was 82.5. The SLESS score was 7.5 (3.6), range 0–15, and its alpha reliability in the same SLE group was 83.9. The SLAQ score and SLESS were correlated at r=0.738, and the strength of association was not improved by non-linear transformations.

As the SLESS and SLAQ scores were highly correlated, we next undertook a series of analyses using the SLESS to evaluate the relation of SLE symptoms and fibromyalgia in patients with SLE, arthritis and fibromyalgia. The mean age and percent males for the three diagnostic groups were as follows: SLE 50.3 (13.6) years, 6.2%; fibromyalgia 56.8 (12.9) years, 4.7% male; and arthritis 57.9 (10.3) years, 22.8% male.

SLESS levels in SLE, fibromyalgia and arthritis

As a preliminary to evaluating the relationship between SLE and fibromyalgia, we first examined the level of SLE symptoms and other symptoms in SLE and arthritis patients (Table 1). Not surprisingly, as the SLESS was designed to evaluate SLE symptoms, the SLESS score was considerably greater in SLE patients compared with those with arthritis, 7.2 (3.7) vs. 4.5 (3.1), p <0.001 (Table 1). However, there was no difference in SLESS scores in patients with SLE compared with fibromyalgia (7.2 (3.7) vs. 7.3 (3.0).

Analysis of SLE symptoms across diagnostic groups

We examined the prevalence of SLESS items in the diagnostic groups (Table 2 and Figures 1 and 2). For ease of understanding the arthritis group contribution, we show the group split into its constituent components (RA and non-inflammatory rheumatic disorders) in the table. Table 2 provides descriptive data and Figures 1 and 2 provide odds ratios and confidence intervals. Comparing SLESS items in SLE and arthritis patients, Figure 1 and Table 2 show that all symptoms were more common in SLE than in RA and non-inflammatory rheumatic disorders, but Raynaud’s, rash and fever were particularly increased.

Table 2.

Percent of patients positive for SLE Symptom Scale (SLESS) by Diagnostic Category

| SLE % (N= 834) | FS % (N=2,397) | RA % (N=16,884) | NIRD % (N=3,206 ) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More common in SLE than FS (p<0.05) | Raynaud's (%) | 39.5 | 18.2 | 9.2 | 6.0 |

| Rash (%) | 62.6 | 37.9 | 25.4 | 20.0 | |

| Fever (%) | 18.6 | 12.3 | 5.4 | 4.0 | |

| Easy bruising (%) | 60.0 | 47.7 | 42.0 | 37.2 | |

| Hair Loss (%) | 31.7 | 23.8 | 17.4 | 13.0 | |

| Equally common in SLE & FS (p>0.05) | Rash (other) (%) | 15.4 | 14.2 | 7.0 | 5.7 |

| Shortness of breath (%) | 39.3 | 38.1 | 24.0 | 24.4 | |

| Seizures (%) | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | |

| Anorexia (%) | 20.6 | 21.4 | 12.8 | 9.7 | |

| Joint pain or swelling (%) | 79.9 | 81.0 | 74.8 | 76.6 | |

| More common in FS than SLE (p<0.05) | Headache (%) | 53.4 | 62.1 | 29.2 | 28.6 |

| Abdominal pain (%) | 41.1 | 53.8 | 23.7 | 24.9 | |

| Stroke/paresthesias (%) | 54.0 | 67.4 | 37.1 | 40.4 | |

| Fatigue (%) | 77.2 | 86.0 | 59.4 | 55.0 | |

| Cognitive problems (%) | 57.4 | 72.6 | 38.3 | 39.3 | |

| Muscle pain or weakness (%) | 65.5 | 88.5 | 47.5 | 48.6 | |

SLE: Systemic lupus erythematosus

FS: Fibromyalgia

RA: Rheumatoid arthritis

NIRD: Non-inflammatory rheumatic disorders

We next compared the relative association of SLESS items with the diagnosis of SLE and fibromyalgia. As shown in Figure 2, headache, abdominal pain, stroke or paresthesias, fatigue, cognitive problems and muscle pain/weakness are more common in fibromyalgia than SLE and Raynaud’s, rash, fever, easy bruising and hair loss are more common in SLE.. The horizontal lines in Table 2 separate the variables that are more or less common in SLE compared with fibromyalgia. Overall, these analyses define sets of variables found in the SLESS and the SLAQ that are more and less associated with fibromyalgia in patients with SLE.

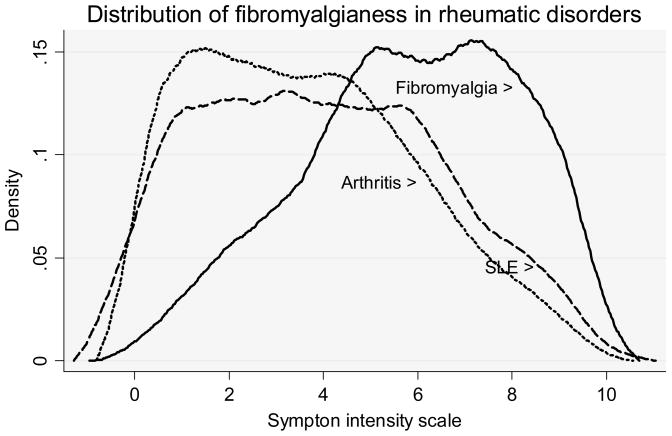

Fibromyalgianess & fibromyalgia in SLE

We used the Symptom Intensity (SI) scale to measure the extent of fibromyalgia symptoms in patients in the different diagnostic groups (Table 1). The SI score was minimally, but significantly, increased (0.4 units) in SLE compared with arthritis, but substantially increased in fibromyalgia (2.2 units) compared with arthritis. The distribution of fibromyalgianess among the 3 diagnostic groups can also be seen in Figure 3 where the distributions can be seen to be similar in SLE and arthritis, but shifted to the right in fibromyalgia. In addition, using the suggested cutoff for diagnosis of survey fibromyalgia of ≥ 8 for the RPS and ≥ 6 for VAS fatigue, 22.1% of SLE patients and 17.0% of arthritis patients would satisfy those criteria. When only data from women were analyzed, the respective proportions were 22.0% and 18.3%. These data indicate a small increase in the prevalence of survey fibromyalgia in SLE compared to arthritis and a minimal increase in fibromyalgianess.

Figure 3.

The distribution of Symptom Intensity Scale scores, a measure for fibromyalgianess, in 961 patients with SLE, 2,409 with fibromyalgia, and 20,141 with “arthritis.” In this figure, arthritis represents rheumatoid arthritis (N=16,910) or non-inflammatory rheumatic disorders (N=3,231). Plots are kernel density estimates.

Are SLE symptom scales biased by fibromyalgia content?

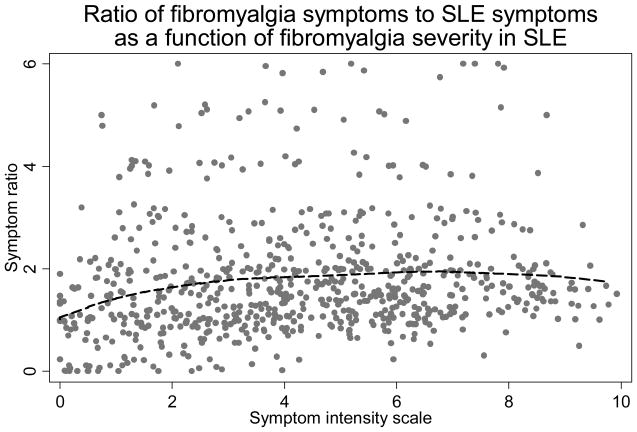

As shown above, the SLAQ and SLESS scales are mixtures of symptom items, some of which are more likely to be endorsed by patients with fibromyalgia and some by patients with SLE. We studied the ratio of the fibromyalgia items (headache, abdominal pain, paresthesias/stroke, fatigue, cognitive problems and muscle pain or weakness) to the SLE items (Raynaud’s, rash, fever, easy bruising and hair loss) at different levels of the SI scale to determine if the ratio was constant over different levels of fibromyalgianess in patients with SLE. As shown in Figure 4, the ratio was constant over the range of SI scores and there was no evidence of a disproportionate fibromyalgia symptom reporting associated with increasing fibromyalgianess. In addition, we examined the relation between the SLESS and the SI scale in a fractional polynomial regression of SLESS on the SI scale. The non-linear model was not significantly better (p=0.087). These data indicate that SLE symptoms scales and the SLESS scores are not biased by the degree of fibromyalgianess in patients with SLE.

Figure 4.

Ratio of the count of fibromyalgia symptoms to SLE symptoms from the SLESS as function of fibromyalgianess (SI scale) in SLE displayed using Lowess regression. Fibromyalgia symptoms from the SLE symptom scale are headache, abdominal pain, paresthesias/stroke, fatigue, cognitive problems and muscle pain or weakness, and SLE symptoms are Raynaud’s, rash, fever, easy bruising and hair loss. This figures shows that the ratio is constant over the range of the SI scale.

Fibromyalgia in self-reported, but unconfirmed diagnoses of SLE

Although patients with unconfirmed SLE were excluded from the above analyses, there is a general interest in whether patients reporting to physicians that they have been diagnosed with SLE might have a high prevalence of fibromyalgia. We found that self-reported SLE was associated with an increased prevalence of fibromyalgia when unconfirmed by physicians compared to confirmed SLE. Survey fibromyalgia was found in 22.1% of confirmed SLE and 33.4% not confirmed or not yet confirmed.

Discussion

We have shown elsewhere that the latent concept of fibromyalgia, here measured by the SI scale, represents a general human response to illness and stress, and, as such, is influenced by illness severity and socio-demographic characteristics (16). Therefore, we should expect to find a proportion of patients with high levels of fibromyalgianess in all rheumatic diseases. Using survey fibromyalgia criteria, 22.1% of SLE patients and 17.0% of arthritis patients could be diagnosed as having fibromyalgia.

A better sense of fibromyalgianess in SLE that does not rely on arbitrary cut points can be seen in Figure 3 in which patients with SLE differ from those with arthritis by a slight shifting of the distribution curves to the right. Based on these data it appears that arthritis and SLE are similar with respect to fibromyalgia prevalence and fibromyalgianess; however, prevalence is increased slightly in SLE compared to arthritis. This difference could represent a real difference based on the nature of SLE or could represent diagnostic differences among physicians, a sampling effect.

The issue of fibromyalgia and fibromyalgianess intrudes into diagnosis when SLE “soft” criteria items are used to satisfy classification criteria, and fibromyalgia patients report more symptoms than those without fibromyalgia (Tables 1 and 2). The ACR SLE criteria (1;2), which require at least four positive items and which may be obtained historically, include photosensitivity, oral or nasopharyngeal ulcers, pleuritis or pericarditis, and seizures. In the presence of a positive anti-nuclear antibody, only three of the above items are required. As shown in Table 2 and described in the results, persons with fibromyalgia report these finding more frequently than those with RA and non-inflammatory rheumatic disorders. The symptom increase in fibromyalgia appears to be important: we noted that survey fibromyalgia prevalence in self-referred patients with SLE was 33.4% compared with 22.1% for self-referred patients with physician confirmed diagnosis. This reinforces the need for skilled professional diagnosis in SLE. The SLE criteria are currently being revised and elimination of some of the softer items is a distinct possibility.

The evaluation of SLE activity is also complex. Of the five SLE-specific items we identified, only one is represented as an ACR SLE criteria item, and only two are part of the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) (26). Among the concerns associated with the SLAQ and SLAM is that the items of the SLAQ score, and some in the underlying Systemic Lupus Activity Measure, are self-reported and therefore may be distorted by the symptoms that common in fibromyalgia. However, when we examined fibromyalgia from the point of view of fibromyalgianess (SI scores), we did not find a disproportionate increase in SLESS or SLAQ scores in patients with SLE nor in the ratio of SLE to fibromyalgia variables (Figure 4). Instead we found smooth increase in both SLAQ and SI scale scores (r=0.676) and between SLESS and SI scale (r=0.623). Figure 3 offers further insight into this issue, for it can be seen that there is little difference between the distributions in the SI scale in arthritis and SLE patients while the scale is shifted to the right in patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia.

The prevalence of fibromyalgia in SLE has been the subject of a number of investigations. Middleton et al. studied 102 patients from a public hospital SLE clinic; 22 (22%) met the American College of Rheumatology criteria for fibromyalgia (10), and another 24 (23%) had clinical fibromyalgia but did not meet the classification criteria (3). Gladman et al. found a prevalence of 22% in 119 clinic SLE patients (4). In the John Hopkins Lupus Cohort, 17.3% of 173 SLE patients had ≥11 tender points (5). In an Indian tertiary referral center cohort, Handa et al found fibromyalgia in 8.2% of 158 patients (6). In a Mexican clinic, Valencia-Flores et al. reported 9.5% of 106 SLE patients satisfied ACR criteria (7). In the LUMINA (lupus in Minorities) study, Friedman et al. reported a prevalence of fibromyalgia of 5% in 266 SLE patients (8). Finally, Neumann and Buskila reported that up 65% of patients with SLE have fibromyalgia (9).

The accuracy of the ACR fibromyalgia criteria depends on the pressure and technique of the examiner during the tender point examination, which in turn depends on the training of the examiner. Data from the original ACR criteria study showed considerable inter-examiner variability, even with training. It seems likely that the very wide differences in prevalence among clinics is a function of the examiner rather than SLE itself. The advantage of removing the examiner from the diagnostic equation by using the SI scale and survey fibromyalgia criteria is to remove such bias. In addition, this method allows large groups of patients to be studied and reduces costs. Using survey criteria, we noted that 22.1% of SLE patients satisfied these criteria. Even so, criteria are inherently flawed because the use of a cut point, whether in survey criteria or through the use of the tender point count in the ACR fibromyalgia criteria, result in an artificial separation of patients with very similar characteristics (18), for example those fibromyalgia (+) patients with 11 tender points and those fibromyalgia (−) patients with 10 tender points.

A better approach, we believe, is to use the SI scale as a continuous scale, as it eliminates all of the problems noted above. The SI scale is the most sensitive and best correlated available index for fibromyalgia-associated variables (16). One would expect, given the fibromyalgia prevalence of 22.1% in SLE and 17.0% in arthritis, that the SLE patients would score slightly higher for the SI scale compared with arthritis patients, but that fibromyalgia patients would have still higher scores, and that is what we found.

The SI scale also allows us to test the association between fibromyalgianess and SLE activity rather than dichotomizing SLE patients into fibromyalgia (+) and fibromyalgia (−) subjects. The correlation between fibromyalgianess (SI scale) and SLE activity (SLAQ) was 0.676. This finding of the association between an activity scale and the SI scale is constant across many rheumatic conditions.

Among the limitations of this study is that the SLESS and the SLAQ are not the same scale, and it is possible that study results might have been somewhat different if the SLAQ had been administered to all patients. In addition, the SLESS, unlike the SLAQ, cannot be considered an activity scale. However, within the context of fibromyalgia associations both scales function similarly.

pIn summary, fibromyalgia and fibromyalgianess are slightly increased in SLE compared with arthritis patients. SLE activity scales are strongly correlated with measures of fibromyalgianess. However, there is no evidence that fibromyalgia or increased levels of fibromyalgianess disproportionately distort the SLE activity scales studied.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Frederick Wolfe, National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases, Wichita, Kansas, University of Kansas School of Medicine, Wichita, Kansas

Michelle Petri, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland

Graciela S. Alarcón, University of Alabama – Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama.

John Goldman, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia

Eliza F. Chakravarty, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California

Robert S. Katz, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois.

Elizabeth W. Karlson, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Kaleb Michaud, University of Nebraska and National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases, Omaha, NE and Wichita, KS.

Reference List

- 1.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(9):1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Middleton GD, Mcfarlin JE, Lipsky PE. The prevalence and clinical impact of fibromyalgia in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37(8):1181–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Gough J, MacKinnon A. Fibromyalgia is a major contributor to quality of life in lupus. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(11):2145–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akkasilpa S, Goldman D, Magder LS, Petri M. Number of fibromyalgia tender points is associated with health status in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(1):48–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handa R, Aggarwal P, Wali JP, Wig N, Dwivedi SN. Fibromyalgia in Indian patients with SLE. Lupus. 1998;7(7):475–8. doi: 10.1191/096120398678920497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valencia-Flores M, Cardiel MH, Santiago V, Resendiz M, Castano VA, Negrete O, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with fibromyalgia in Mexican patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2004;13(1):4–10. doi: 10.1191/0961203304lu480oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman AW, Tewi MB, Ahn C, McGwin G, Jr, Fessler BJ, Bastian HM, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups: XV. Prevalence and correlates of fibromyalgia. Lupus. 2003;12(4):274–9. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu330oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neumann L, Buskila D. Epidemiology of fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2003;7(5):362–8. doi: 10.1007/s11916-003-0035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia: Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160–72. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Croft P, Schollum J, Silman A. Population study of tender point counts and pain as evidence of fibromyalgia. Br Med J. 1994;309:696–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6956.696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croft P, Burt J, Schollum J, Thomas E, Macfarlane G, Silman A. More pain, more tender points: is fibromyalgia just one end of a continuous spectrum? Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55(7):482–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.7.482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wessely S, Hotopf M. Is fibromyalgia a distinct clinical entity? Historical and epidemiological evidence. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 1999;13(3):427–36. doi: 10.1053/berh.1999.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolfe F. The relation between tender points and fibromyalgia symptom variables: evidence that fibromyalgia is not a discrete disorder in the clinic. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(4):268–71. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.4.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz RS, Wolfe F, Michaud K. Fibromyalgia diagnosis: A comparison of clinical, survey, and American College of Rheumatology criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):169–76. doi: 10.1002/art.21533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfe F, Rasker JJ. The Symptom Intensity Scale, fibromyalgia, and the meaning of fibromyalgia-like symptoms. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(11):2291–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolfe F. Pain extent and diagnosis: development and validation of the regional pain scale in 12,799 patients with rheumatic disease. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(2):369–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altman DG, Royston P. The cost of dichotomising continuous variables. BMJ. 2006;332(7549):1080. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7549.1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolfe F, Michaud K. The effect of methotrexate and anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy on the risk of lymphoma in rheumatoid arthritis in 19,562 patients during 89,710 PERSON-YEARS of observation. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(5):1433–9. doi: 10.1002/art.22579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolfe F, Caplan L, Michaud K. Treatment for rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of hospitalization for pneumonia: Associations with prednisone, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(2):628–34. doi: 10.1002/art.21568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolfe F, Michaud K. Severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA), worse outcomes, comorbid illness, and sociodemographic disadvantage characterize RA patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(4):695–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfe F. Fatigue assessments in rheumatoid arthritis: comparative performance of visual analog scales and longer fatigue questionnaires in 7760 patients. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(10):1896–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karlson EW, Daltroy LH, Rivest C, Ramsey-Goldman R, Wright EA, Partridge AJ, et al. Validation of a Systemic Lupus Activity Questionnaire (SLAQ) for population studies. Lupus. 2003;12(4):280–6. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu332oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yazdany J, Yelin EH, Panopalis P, Trupin L, Julian L, Katz PP. Validation of the systemic lupus erythematosus activity questionnaire in a large observational cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(1):136–43. doi: 10.1002/art.23238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bae SC, Koh HK, Chang DK, Kim MH, Park JK, Kim SY. Reliability and validity of systemic lupus activity measure-revised (SLAM-R) for measuring clinical disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2001;10(6):405–9. doi: 10.1191/096120301678646146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Caron D, Chang CH. Derivation of the SLEDAI - A Disease Activity Index for Lupus Patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:630–40. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]