Abstract

Large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels (BK) are expressed in principal cells (PC) and intercalated cells (IC) in mammalian nephrons as BK-α/β1 and BK-α/β4, respectively. IC, which protrude into the lumens of tubules, express substantially more BK than PC despite lacking sufficient Na-K-ATPase to support K secretion. We previously showed in mice that IC exhibit size reduction when experiencing high distal flows induced by a high-K diet. We therefore tested the hypothesis that BK-α/β4 are regulators of IC volume via a shear stress (τ)-induced, calcium-dependent mechanism, resulting in a reduction in intracellular K content. We determined by Western blot and immunocytochemical analysis that C11-Madin-Darby canine kidney cells contained a predominance of BK-α/β4. To determine the role of BK-α/β4 in τ-induced volume reduction, we exposed C11 cells to τ and measured K efflux by flame photometry and cell volume by calcein staining, which changes inversely to cell volume. With 10 dynes/cm2, calcein intensity significantly increased 39% and monovalent cationic content decreased significantly by 37% compared with static conditions. Furthermore, the shear-induced K loss from C11 was abolished by the reduction of extracellular calcium, addition of 5 mM TEA, or BK-β4 small interfering (si) RNA, but not by addition of nontarget siRNA. These results show that BK-α/β4 plays a role in shear-induced K loss from IC, suggesting that BK-α/β4 regulate IC volume during high-flow conditions. Furthermore, these results support the use of C11 cells as in vitro models for studying BK-related functions in IC of the kidney.

Keywords: potassium, volume regulation, mechanotransduction, intercalated cells, parallel plate flow chamber, calcein

in the distal nephron of the kidney, the connecting tubules (CNT) and cortical collecting ducts (CCD) consist of two primary epithelial cell types: the principal cells (PC) and the intercalated cells (IC). The PC mediate potassium (K) secretion as well as sodium (Na) and water reabsorption, while the IC mediate acid/base transport. Under normal conditions, K secretion by the PC is mediated primarily by the ROMK channel (9, 26). However, with high distal flow or K-adapted conditions, K secretion in the distal nephron is mediated by the large conductance, calcium-activated K channels (BK) (1, 33, 38, 46).

BK are composed of both pore-forming α- and accessory β-subunits. Four known β-subunits (β1–β4; gene: Kcnmb1–4) along with several splice variants of the α-subunit give the BK an array of different biophysical and pharmacological properties to fulfill tissue-specific functions (15). It is now evident that BK are in a variety of different renal cells with different subunits that tailor the BK properties to the specific functions and demands of the cell. In K-adapted conditions, BK-α/β1 secrete K in the PC of the connecting tubules (14). In Na-deficient conditions, BK-α/β1 are expressed in the basolateral membrane of CCD PC, where they may increase the driving force for Na reabsorption (13).

IC, which are large, cuboidal cells that protrude farther into the lumen than PC, express substantially more BK than PC (31). This is an interesting observation considering that IC lack sufficient Na-K-ATPase activity to support sustained K secretion, even in K-adapted conditions (20). This protrusion by IC narrows the lumen and could cause disturbances in the flow field of tubule fluid. In ouabain-swollen PC from rabbit cortical collecting tubule (CCT), BK play a role in regulatory volume decrease (40). Under high-flow conditions, activating BK in IC in the absence of K-replenishing Na-K-ATPase could similarly lead to a substantial reduction in IC K content, which would yield a reduction in IC volume, thereby reducing the IC luminal profile and increasing the luminal cross-sectional area of the distal segments.

We recently showed that under K-adapted conditions, high distal flow induced in wild-type mice, but not in Kcnmb4−/−, a reduction in IC size with a concomitant increase in luminal cross-sectional area (20). However, it was not determined whether the BK-β4-dependent reduction in IC size was mediated by shear stress (τ) due to the increased luminal flow induced by K adaptation or by other signaling pathways induced by the high K intake. Furthermore, the quantity of τ necessary to induce BK-β4-dependent K loss is not known.

We hypothesized that under high-flow, high-τ conditions, IC lose intracellular K and volume by BK-α/β4. To address this hypothesis, we employed the previously described C11 subpopulation of Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells. C11 have characteristics similar to IC including low transepithelial resistance an intracellular pH of 7.16, and PNA-positive (β-IC) and -negative (α-IC) populations (10, 49). Furthermore, aldosterone and cAMP both stimulate H secretion in C11 (10).

We found that C7 and C11 contained BK-β1 and BK-β4, respectively, mimicking the BK-β profiles of PC and IC in vivo (15). In response to 10 dynes/cm2, C11 undergo BK-α/β4-mediated K efflux and volume reduction. These results support the hypothesis that BK-α/β4 plays a role in τ-mediated reduction of the volume of intercalated cells lining the distal tubule walls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Experiments in this study employed MDCK cells (passages 53–60 from American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD), C7-MDCK cells (passages 75–80, a generous gift of Dr. Bonnie L. Blazer-Yost of Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, IN), a subclone of MDCK with characteristics of PC (10), and C11-MDCK cells (passages 64–70, a generous gift of Dr. Hans Oberleithner of Münster University). All cells were grown in high-glucose DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 25 μg/ml gentamicin under standard incubation conditions of 37°C, 95% humidity, 5% CO2.

Buffers, chemicals, drugs, and reagents.

The physiological saline solution (PSS) contained 135 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM HEPES, pH to 7.4 with NaOH. The isotonic solution contained 135 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM MgSo4·7H2O, 3.3 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM HEPES, and 5.5 mM glucose, pH to 7.4 with NaOH, with a final osmolality of 286 mosmol/kgH2O. The hypotonic solution was the isotonic solution with only 85 mM NaCl (186 mosmol/kgH2O), and the hypertonic solution was the ISO solution with an additional 100 mM mannitol (336 mosmol/kgH2O). Osmolality was measured by freezing-point depression (model 3250, Advanced Instruments, Norwood, MA). Distal tubule buffer (DTB), which is similar to mammalian distal tubule luminal fluid, contained 65 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 5 mM urea, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.4 mM MgSO4, supplemented with 3.3 mM NaHCO3, 5 mM HEPES, and 2 mM glucose, pH to 6.5 with HCl. Final osmolality was ∼150 mosmol/kgH2O. PBS was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Fura 2-AM (7 μM), calcein-AM (10 μM), and Pluronic F-127 were obtained from Invitrogen (formerly Molecular Probes) and resuspended in DMSO. Unless otherwise denoted, all other chemicals and solutions were obtained from Sigma.

Western blotting.

Standard Western blotting was performed as previously described (15) following the manufacturer's protocol (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) using 20 μg of sample protein. Primary antibodies included anti-BK-α (rabbit polyclonal, diluted 1:1,000, Alomone Labs), anti-BK-β4 (rabbit polyclonal, diluted 1:1,000, Alomone Labs), and anti-actin (rabbit polyclonal, 1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) with either donkey (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or goat (Pierce Biotechnology) anti-rabbit IgG-conjugated horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody diluted 1:20,000–1:40,000. Expression of primary antibodies was quantified by densitometry.

Small interfering RNA.

Knockdown of the BK-β4 subunit in C11 cells was achieved by transfection with 3 μg small interfering RNA (siRNA) using the siGENOME SMART pool (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO). The siGENOME SMART pool consists of four nucleotide oligos specifically designed for human BK-β4 (Kcnmb4, NM_014505) with the following target sequences (CAACAGUGGAAAGAUG, GUACUGGAAAGAUGAGAUU, GAGAUUGUCCUCCUGCAUU, and GCGUCCAGGUCUACGUGAA). The human BK-β4 siRNA oligos all had 100% homology with the predicted canine BK-β4 (XM_531677). Additionally, two custom siRNA oligos were designed specifically for the canine with the following target sequences (AAGCAGAAGCCAUGAAGAA and CCUCCCUGUAAGAGAGAA). Optimal silencing occurred when all six targeting oligos were used in combination. A second pool of four nontargeting siRNA oligos were used for negative-control experiments (Dharmacon nontargeting siGENOME SMART pool 2). C11 were transfected by electroporation according to the manufacturer's instructions as previously described (52).

Parallel-plate flow system.

Cells were grown to confluence on glass parallel plates (3–4 days) and incubated for another 3–4 days. Cells were exposed to 0 (static), 1, 2.5, 5, or 10 dynes/cm2 τ in a parallel-plate flow chamber (PPFC; C&L Instruments, Hershey, PA) at 37°C for either 30 min or 5 h. The PPFC consists of a 24 × 40-mm rectangular flow chamber with a chamber height of 100 μm. Perfusate (DTB) was pumped through the PPFC by a peristaltic pump (Masterflex Easy load model 7518–10, Cole-Palmer, Vernon Hills, IL). Each glass parallel plate was held in place by vacuum suction and sealed by dual O-rings with a solid structure behind the plate. Neither changes in flow rates nor peristaltic flow conditions moved the plates; therefore, any membrane stretch due to distention was eliminated. After exposure to τ, cells were lysed with 2 ml ice-cold distilled H2O, scraped, vortexed, and centrifuged at 10,000 RCF for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected, and K and Na levels were measured by flame photometry (model PFP7/C, Jenway, Barloworld Scientific, Essex, UK). The cell pellet was resuspended in PBS with 2 mg/ml RNase A for 2 min at room temperature. Cellular DNA was isolated by a DNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer's procedures. Resuspended DNA was heated to 55–60°C for 10 min and then measured with a spectrophotometer (Genesys 5, Spectronic Instruments) at 260 and 280 nm. Monovalent cation content was normalized by DNA to adjust for cells lost during flow or variances in cell number between samples.

Immunocytochemical staining.

For immunocytochemical staining, cells were stained as previously described (45). Primary antibodies (anti-BK-α, mouse monoclonal, NeuroMab, Univ. of California, Davis, CA; anti-BK-β1, rabbit polyclonal, Affinity BioReagents, Golden, CO; anti-BK-β4, rabbit polyclonal, Alomone Labs; all were diluted 1:50) or antibody species-specific IgG (negative control) at equal concentrations were incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing, cells were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in the dark with the secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse IgG-conjugated Alexa Fluor 488 or donkey anti-rabbit IgG-conjugated Alexa Fluor 594, diluted 1:200 in blocking buffer) followed by nuclear staining with 0.25 μg/ml Hoechst 33258 for 10 min in the dark at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted onto microscope slides with Prolong Gold (Invitrogen), sealed with nail polish, and viewed on a confocal microscopy; slides were viewed on a Zeiss LSM 510 META Confocal microscope with a ×63/1.4-numerical aperture Plan-Apochromat objective. Vertical plane images were acquired at 0.5- or 1-μm optical slices. Captured images were analyzed with ImageJ software (version 1.42, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Calcein imaging.

A confluent monolayer of C11-MDCK cells were loaded with the volume-sensing dye calcein-AM in PSS for 10 min in a cell culture incubator, then rinsed once with PSS and placed in the PPFC. Calcein fluorescence intensity was measured on an Olympus X71 inverted fluorescent microscope using a ×20/0.4-numerical aperture Fluor objective and a QImaging QICAM CCD camera (model QIC-F-M-12, Surrey, BC) and analyzed with ImageJ software. Fluorescence was measured at an emission wavelength of 525 nm in response to an excitation wavelength of 495 nm.

For calcein intensity to be proportional to the cell volume, the optical section height must be thinner than the cell height at all cell volumes. Therefore, calcein cell volume measurements are typically made using either confocal optical sectioning or a high numerical objective. For widefield microscopy, the optical section is approximately the depth of field, which is the sum of the wave and geometrical optical depths of fields

where df is the total depth of field, λo is the fluorescent wavelength of light (525 nm), n is the refractive index (1 for air), NA is the numerical aperture (0.4), M is the objective magnification (20), and e is the smallest resolution distance for the given objective in the image plane (15). The depth of field is 5.15 μm, which is approximately one-half of the C11-MDCK cell height (see Fig. 2) and thinner than the cell height at all cell volumes.

Fig. 2.

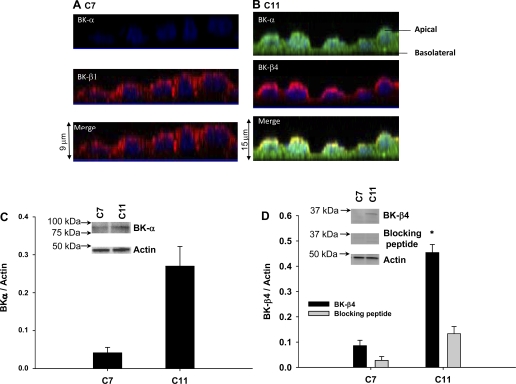

Expression of calcium-activated potassium channel BK-α and -β subunits in C7 and C11 cells by immunocytochemistry. A: yz-plane stacked view of multiple 1-μm slices of cells where C7 stained with rabbit IgG control or BK-α (green) and BK-β1 (red) antibodies. B: C11 stained with rabbit IgG control or BK-α (green) and BK-β4 (red) antibodies. C: Western blot of BK-α, BK-β4, BK-β4 with blocking peptide, and actin. D: Western blot band density was normalized to actin. All symbols are same as in Fig. 1 (n = 3).

In each experiment, calcein intensity was measured from six cells at baseline and again at 5 and 30 min after exposure to either static or flow conditions. After background correction, calcein fluorescence intensity was averaged from the six cells for either static or flow conditions and normalized to the average baseline intensity. Experiments were repeated five times.

Calcium imaging.

Intracellular calcium concentrations ([Ca2+]i) were measured as previously described (5, 27). Cells were placed in the PPFC and perfused with DTB at 37°C and 10 dynes/cm2 using a syringe pump (model 100, Kd Scientific Holliston, MA). Cells were excited at 340 and 380 nm (±3-nm bandwidths) by a DeltaScan dual monochromator system (Photon Technology International, Birmingham, NJ). Fura 2 emission was detected by a photon-counting photomultiplier at 510-nm emission ( ±20-nm bandwidth, Photon Technology International) from a single cell. Background corrected data were collected, and calibration of fura 2 was performed according to established methods (16). Data were collected at 10 Hz, stored, and processed with the FeliX software package (version 1.1, Photon Technology International).

Statistical methods.

Data shown in figures represent means ± SE. Unless otherwise denoted, data were analyzed by a paired t-test with the static controls, which were run simultaneously using the same batch of cells, buffers, reagents, and incubation time. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be significant. We performed data management and statistical analyses using Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) unless denoted.

RESULTS

τ-Induced cationic efflux.

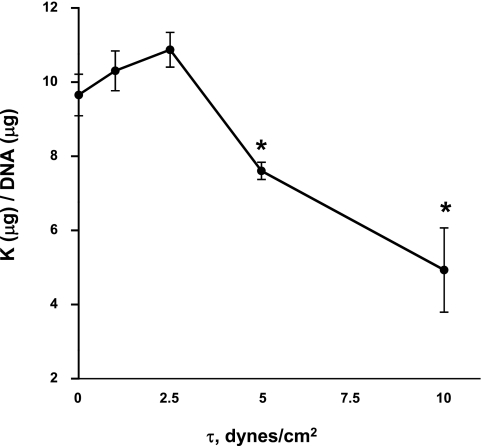

To determine whether MDCK cells possess a τ-dependent volume-regulatory mechanism, we exposed MDCK cells to 0, 1, 2.5, 5, and 10 dynes/cm2 and measured intracellular K efflux (Fig. 1). Changes in cellular K content would reflect changes in cell volume, thus a measure of relative cell volume. Compared with static conditions (0 dynes/cm2), 1 and 2.5 dynes/cm2 did not produce significant changes in intracellular K in MDCK cells; however, in response to 5 dynes/cm2, the intracellular K content of MDCK cells significantly decreased by 21% compared with static (Fig. 1, P < 0.05). In addition, 10 dynes/cm2 caused a decrease in intracellular K by 48% compared with static conditions (P < 0.02). We chose 10 dynes/cm2 for further experimentation because 10 dynes/cm2 was effective and is well within the range of normal τ (0.37–23.8 dynes/cm2) experienced in the mouse CCD (48).

Fig. 1.

Potassium efflux from Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells exposed to variable shear stresses (τ). MDCK cells were exposed to either 0 (static), 1, 2.5, 5, or 10 dynes/cm2 in a parallel-plate flow chamber (PPFC). Compared with the static condition, 5 and 10 dynes/cm2 produced K efflux. Values are means ± SE (n = 5). *Significant difference (P < 0.05).

Expression of BK channels in C7 and C11 cells.

Figure 2 shows the expression of BK-α and β-subunits of C7-MDCK (Fig. 2A) and C11-MDCK (Fig. 2B) by immunocytochemistry using line-scanning confocal microscopy. C7 expressed very low levels of BK-α, but did express BK-β1 at the apical membrane (Fig. 2A). However, C11 expressed BK-α throughout the cell, particularly at the apical membrane where it colocalized with the BK-β4 subunit (Fig. 2B). Similar to the BK-β1 subunit in C7, the BK-β4 subunit was almost exclusively expressed in the apical membrane of C11.

Previous studies have shown low levels of BK-α expression in PC in mice (15) and rats (31). Therefore, we further investigated BK channel expression in C7 and C11 cells by Western blot analysis, which is typically more sensitive than immunocytochemistry. Western blot analysis showed mild BK-α expression in C7 (Fig. 2C) and abundant BK-α and BK-β4 expression in C11 (Fig. 2, C and D). Band density of BK-β4 in C11 was diminished by 70% by the addition of a blocking peptide, demonstrating the specificity of this antibody (Fig. 2D). C7 did not express BK-β4 (Fig. 2D). These results demonstrate that C7 and C11 have the same BK component expression as PC and IC in vivo (15). Furthermore, as we have previously shown in vivo using Kcnmb4−/− mice (20), BK-β4 is not required for apical expression of BK-α in IC.

τ-Induced volume regulation in C11 cells.

To better determine the role of τ-induced volume regulation, we exposed calcein-AM-loaded C11 cells to either static conditions or 10 dynes/cm2 for 30 min with DTB buffer and measured calcein fluorescent intensity. We chose 10 dynes/cm2 because 10 dynes/cm2 is well within the range of normal τ (0.37–23.8 dynes/cm2) experienced in the mouse CCD (48). Calcein-AM is a dye retained in cells upon cleavage of the methyl ester and is not sensitive to changes in intracellular ionic composition (22). Calcein fluorescent intensity is inversely related to cell volume; i.e., calcein fluorescent intensity increases during cell shrinkage as the calcein dye becomes more concentrated and decreases during cell swelling.

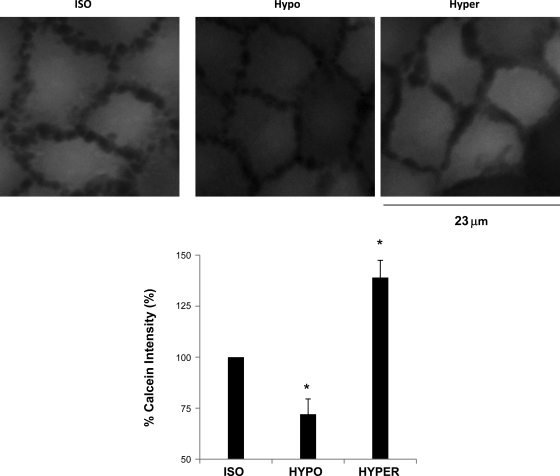

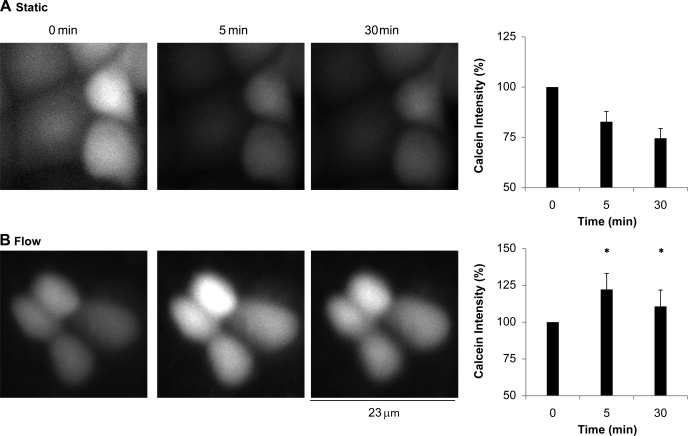

To test our experimental conditions, calcein-loaded C11 cells were exposed to isotonic buffer for 5 min and to either hypotonic or hypertonic buffers for 30 min. The results are shown in Fig. 3. Compared with isotonic conditions, calcein intensity of C11 cells in hypotonic buffer decreased by 27% (P < 0.01, n = 5). However, calcein intensity of C11 cells in hypertonic buffer increased by 39% (P < 0.01, n = 5) compared with isotonic conditions. These results verified our calcein assay. We then exposed calcein-loaded C11 cells to static conditions or 10 dynes/cm2. The results are shown in Fig. 4A. After 5 min in static conditions, the calcein intensity of C11 cells decreased compared with baseline (0 min) by 17%. After 30 min, calcein intensity decreased by 25% compared with baseline. However, C11 cells exposed to 10 dynes/cm2 for 5 min experienced an increase in calcein intensity of 26% compared with baseline (Fig. 4B). This increase in calcein intensity was significantly different than in static conditions (P < 0.02, n = 6). After 30 min of 10 dynes/cm2, calcein intensity was still greater than baseline by an average of 14% and statistically greater than static conditions (Fig. 4B, P < 0.03, n = 6). The slight decline in calcein intensity after 30 min for both the static and flow conditions suggests some quenching or sequestering of calcein over time. We then examined whether BK-α/β4 played a role in τ-induced volume reduction through cellular K efflux.

Fig. 3.

Calcein responses to hypotonic (HYPO) and hypertonic (HYPER) conditions. Calcein assay was verified by exposing C11 cells to isotonic (ISO), HPO, or HYPER solutions for 30 min. Calcein fluorescent intensity was plot for each buffer and normalized to ISO conditions. All symbols are same as in Fig. 1 (n = 5).

Fig. 4.

Volume status measured by calcein intensity of C11 cells exposed to either static (A) or flow (10 dynes/cm2; B) in a PPFC for 5 and 30 min. Compared with baseline, calcein intensity in static conditions decreased after 5 and 30 min by 17 and 25%, respectively; however, with shear stress, calcein intensity increased after 5 (25%) and 30 min (14%). *Significant difference (P < 0.05) from corresponding static condition (n = 6).

τ-Induced cationic efflux.

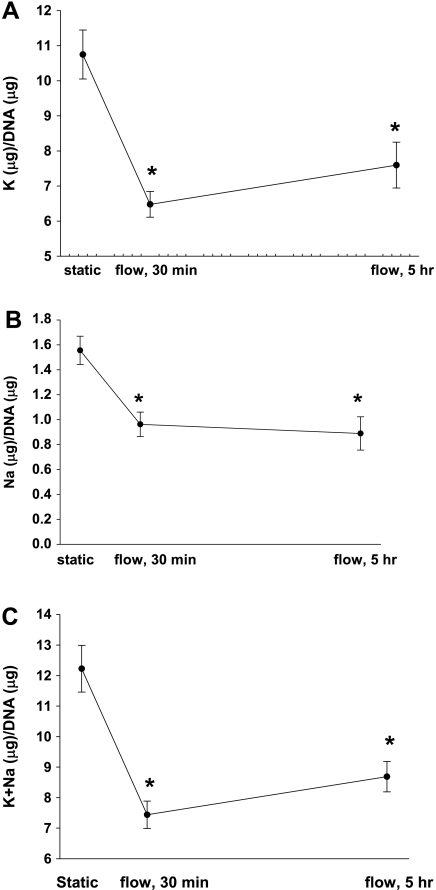

We exposed C11 cells to static and 10 dynes/cm2 for 30 min and measured intracellular K and Na content (Fig. 5A). A K efflux of 39% (P < 0.02, n = 6) was produced at 10 dynes/cm2 as well as a total monovalent cation efflux of 40% (P < 0.03, n = 6) compared with static conditions. To determine whether the K efflux would be maintained for prolonged periods of time similar to in vivo, we exposed C11 cells to 10 dynes/cm2 for 5 h and again measured intracellular K and Na content (Fig. 5). C11, which express BK-α and BK-β4, possessed a τ-induced K efflux of 27% (Fig. 5A, P < 0.02, n = 6). Furthermore, C11 cells also exhibited a Na efflux of 42% (Fig. 5B, P < 0.02, n = 6) and a total monovalent cation efflux of 28% (Fig. 5C, P < 0.02, n = 6). Because the majority (88%) of the τ-induced monovalent cation efflux in C11 cells was K (Fig. 5C) for both 30 min and 5 h, we examined the role of the BK in K efflux in C11 cells.

Fig. 5.

Potassium (n = 6, A), Na (n = 6; B), and K+Na efflux (C) from C11 exposed to 10 dynes/cm2 compared with static in a PPFC at 30 min and 5 h. All symbols are same as in Fig. 1.

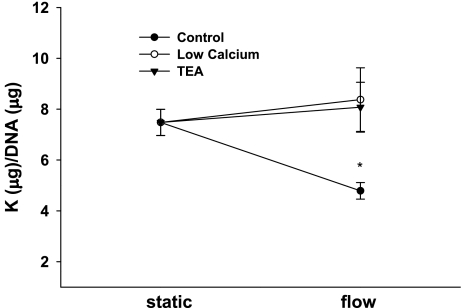

For C11, the τ-induced decrease in intracellular K was attenuated by reducing luminal Ca2+ from 1 mM to 45 μM (Fig. 6, n = 6). The τ-induced cation efflux was also inhibited by 5 mM tetraethylammonium (TEA), a fairly selective BK blocker (Fig. 5, n = 7). These results strongly suggest a role for BK in the K efflux from C11.

Fig. 6.

Potassium efflux from C11 cells exposed to static or 10 dynes/cm2 in a PPFC for 5 h. Compared with static, flow-induced K efflux in control (n = 6), but not with reduced (45 μM) extracellular calcium (n = 6) or 5 mM tetraethylammonium (TEA; n = 7). All symbols are same as in Fig. 1.

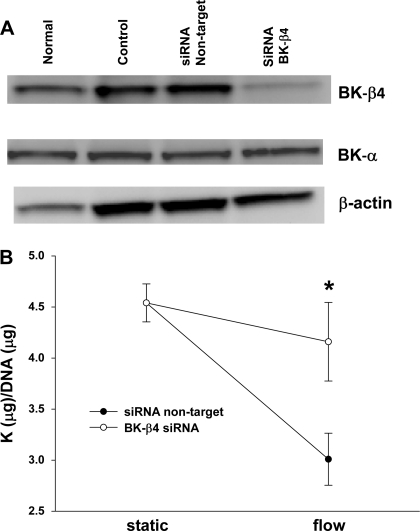

Effects of siRNA BK-β4 on flow-induced K efflux in C11.

We examined the potential role of BK-β in the τ-induced K efflux by transfecting C11 with either green fluorescent protein (control), four nontarget siRNA oligos (siRNA nontarget), or six siRNA oligos for BK-β4 (siRNA BK-β4). The efficiency of knockdown was assessed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 7A). siRNA silenced ∼80% of BK-β4 compared with normal conditions. However, these samples still expressed BK-α (Fig. 7A). BK-β4 siRNA blocked τ-induced K efflux in C11 (Fig. 7B), while the nontarget controls still maintained a τ-induced K efflux (Fig. 7B, P < 0.03).

Fig. 7.

Effects of BK-β4 small interfering (si) RNA on shear-stress (10 dynes/cm2)-induced K efflux from C11. A: C11 were untreated (normal), transfected with green fluorescent protein (control), 4 nontarget siRNA oligos (siRNA nontarget), or 6 siRNA oligos for the BK-β4 subunit (siRNA BK-β4). As assessed by Western blot analysis, BK-β4 siRNA silenced ∼80% of BK-β4 compared with control. There was no effect of siRNA on BK-α expression. B: flow-induced K efflux at 5 h was blocked by BK-β4 siRNA (n = 4), but not by nontarget siRNA (n = 4). All symbols are same as in Fig. 1.

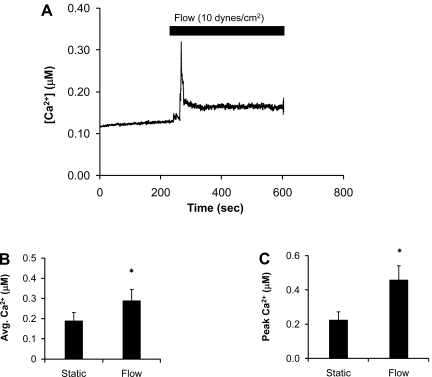

Flow-induced calcium increase in C11.

To examine the effects of flow on [Ca2+]i, we exposed C11 cells to 10 dynes/cm2 and measured [Ca2+]i with fura 2. As previously reported (35), exposure of C11 to 10 dynes/cm2 at 37°C resulted in a transient increase in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 8A), which dissipated over time. Interestingly, this increase in [Ca2+]i was not observed unless the perfusate was at or near physiological temperature, suggesting that the increase in [Ca2+]i occurred through a temperature- and flow-sensitive mechanism (23, 48). Compared with static conditions, exposure of C11 to 10 dynes/cm2 resulted in a significant increase in peak and average steady state [Ca2+]i (Fig. 8, B and C). The average steady-state calcium value (Fig. 8B) was defined as the average fura 2 value for all time points under either static or flow conditions for each experiment including the peak values. However, the peak values had little effect on the overall flow average because there were many more time points in the flow plateau (∼2,000–3,000 time points) following the peak than for the peak itself (∼100 time points).

Fig. 8.

Shear stress (10 dynes/cm2)-dependent, transient calcium increases in C11. A: shear stress transiently increased intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), which returned to near baseline levels. B and C: bar plots summarizing shear stress-induced average (B) and peak [Ca2+]i (C). All symbols are same as in Fig. 1.

DISCUSSION

Several studies have now identified a role for the BK channel in flow-induced K secretion (FIKS) by measuring flow rate-dependent K flux (Jk) in rat and rabbit isolated, perfused distal tubules (24, 29, 41, 46). Clearance studies revealed that FIKS was eliminated in BK-α (38) and BK-β1 (33) knockout mice. Micropuncture showed that iberiotoxin, a BK-inhibitory compound, eliminated FIKS in the late distal tubule of K-adapted mice (1). However, these findings have been complicated by patch-clamp (31) and immunohistochemical studies (15) showing that BK are predominantly expressed in IC, which were not thought to be involved in Na and K transport.

A potential role for IC in K transport has emerged with the finding that K-adapted BK-β4−/− had blunted K secretion and increased Na and water reabsorption (20). Furthermore, we now understand that in K-adapted conditions K is eliminated by a Na-independent pathway not involving the epithelial Na channel (ENaC) and Na-K-ATPase of PCs (8). These findings suggest that BK-α/β4 in the IC either directly or indirectly mediate FIKS.

A previous study from our laboratory showed that PC, but not IC, exhibited increased expression of Na-K-ATPase in K-adapted mice (20). A lack of Na-K-ATPase suggested a nontransport role for the BK-α/β4, which resides in all IC of the CNTs and CCDs. The present study examined the role of BK-α/β4 in C11 in response to τ. We hypothesized and discovered that BK-α/β4 plays a role in C11 volume reduction in a shear-dependent manner. By decreasing IC cell volume and profile under high fluid-flow (i.e., high τ) conditions, tubular resistance will decrease, allowing a more streamlined, rather than constricted and turbulent, distal flow.

We previously showed that a high distal flow reduces IC size in wild-type, but not Kcnmb4−/−, allowing the CNT and CCD to accommodate larger volumes of fluid flow (20). A τ-induced K efflux via BK-α/β4 without a sustained Na-K-ATPase-mediated K entry could account for the net cation efflux and the IC volume decrease observed both in vivo and in vitro (Figs. 2–7). Therefore, this study establishes a distal nephron epithelial-specific cell culture system for examining the role of BK in the distal nephron and indicates that the reduction in IC size observed in vivo is a τ-induced BK-α/β4-mediated K efflux at τ at or above 5 dynes/cm2 (Fig. 1).

Due to the large variations in geometry and fluid flow rates, the distal nephron is exposed to a wide range of τ. Although no in vivo data exist, shear rates in the mouse CCD have been estimated to range from 0.37 to 23.8 dynes/cm2 (48). Other studies have estimated τ as low as 0.52 dynes/cm2 (25) to as high as 30 (4) or 35 dynes/cm2 (50, 51). In our previous study, IC size reduction only occurred in K-adapted mice with high distal tubule-flow conditions, where τ of 5–10 dynes/cm2 is clearly within the physiological range. Furthermore, high τ can induce membrane stretch, which also activates the BK channel (18). Pacha et al. (31) have shown stretch activation of the BK channel that was calcium independent in 38 of 42 cell-attached patches on rabbit IC. Decoupling τ from τ-induced membrane stretch is challenging and would be an interesting future study.

Expression of BK components in C7 and C11.

We showed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2C) that C7 and C11 express BK-α. However, C11 expressed substantially more BK-α than C7 (Fig. 2C) as the BK-α in C7 was only detectable by Western blotting. Although C7 cells have minimal BK-α, they expressed the BK-β1 subunit at the apical membrane. Why C7 expressed apical BK-β1 with little expression of the pore-forming BK-α is not understood. It is possible that C7 cells express a splice variant of BK-α that was not detectable by our antibodies.

Similarly, C11 expressed BK-β4 at the apical membrane, where it colocalized with BK-α. These results match our previous findings for IC and PC in murine CNT and CCD (15) and are consistent with patch-clamp experiments describing a higher frequency of functional BK in IC than PC of rat CCD (32). Therefore, C7 and C11 cells may be good in vitro models for studying the respective physiological roles of the BK-α/β1 in PC and the BK-α/β4 in IC. However, because of the difficulty in patch clamping MDCK cells, few single-channel BK recordings have been documented in these cells (2). Furthermore, the use of a PPFC, which creates a laminar, well-define flow field, prevents the ability to perform single-channel patch-clamp recordings using micropipettes. Furthermore, the validity of C11 cells as in vitro models for acid and base transport was not determined in this study.

Role of the BK channel in flow-mediated K secretion.

Previously, antibodies have recognized Na-K-ATPase proteins on PC but not IC in the distal segments (17, 19, 37). More recently, antigen retrieval and methods for quantifying fluorescent staining have demonstrated the presence of Na-K-ATPase in IC, but the amount was <10% of that found in PC of rats or mice on either a regular diet or a high-K diet for several days (20, 39). A paucity of Na-K-ATPase in IC that does not increase with K adaption suggests “housekeeping” or volume-regulatory roles rather than transporting roles for the basolateral Na-K-ATPase and apical K channels. Moreover, an absence of ENaC (21) is consistent with a non-Na transporting role for Na-K-ATPase in IC.

A “housekeeping” role for Na-K-ATPase in IC was evident by the τ-induced reduction in intracellular Na content. As the IC shrink in response to τ-induced K efflux, the cellular Na will concentrate and stimulate the small amount of Na-K-ATPase, causing Na extrusion, potentially leading to the observed Na efflux in response to τ in C11 cells (Fig. 5). Furthermore, upon the removal of τ-induced K efflux, the Na-K-ATPase is necessary for IC to return to normal K, Na, and water content (28).

The present data show a significant loss of monovalent cation content from C11 in response to τ. This τ-induced K efflux from C11 was attenuated by low Ca2+ and TEA, suggesting a role for the BK channel. This is not surprising considering BK channels are highly expressed in IC and were previously shown to mediate flow-induced K secretion in the isolated rabbit CCD (24, 46). However, our results support an indirect role for BK in IC to increase K secretion. Rather than flow stimulating transepithelial K secretion via IC, which would require basolateral Na-K-ATPase, these data suggest that τ stimulates an IC loss of intracellular K via BK, resulting in volume reduction, which is maintained as long as τ of high flow is maintained (Figs. 4 and 5).

As we have shown previously, the high distal flows of the K-adapted mouse cause a reduction in IC size and increase in the tubule lumen (20). Thus flow-mediated K secretion is BK-α/β4 dependent at least partly because the increased luminal diameter allows for an increased concentration gradient and enhanced K secretion through ROMK or BK in the PC. However, IC still may have a role to secrete K during high distal flows created by a high-K diet. It is known that mammals eliminate as much as 50% of a high-K load by a Na-independent mechanism. Experiments with K-adapted rats show that amiloride (8) only eliminates half of the high-K load, suggesting that the driving force supplied by ENaC and Na-K-ATPase may not be necessary to eliminate K via BK-α/β4 in IC cells. It is not understood how K would be secreted by IC during the K-adapted condition. An active transport mechanism, other than the Na-K-ATPase, which delivers K into the cell, would be necessary. K could be delivered into the cell by the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter; however, for steady-state K entry, the Na would have to be continuously actively extruded.

BK are also located in IC of the CNT, where they serve to reduce cell size. This role for BK is consistent with in vivo studies with BK-α−/− and ROMK−/−, illustrating the dependency of BK on flow-mediated K secretion (1). Rieg et al. (38) showed that flow-mediated K secretion was reduced in BK-α−/−. Genetically deleting BK-β1 (Kcnmb1−/−), normally located in the apical membrane of CNT cells, resulted in a reduction of K excretion induced by volume expansion with the accompanying high Na delivery (33). That the CNT (late distal tubule) was a site of BK-mediated K secretion is supported by a micropuncture study of ROMK−/− (1). Despite lacking K-secretory ROMK channels, ROMK−/− maintained normal K secretion in the late distal tubule by an iberiotoxin-sensitive (BK-mediated) process (1).

With τ, an anionic cell exit pathway must be activated at the same time as BK to preserve electroneutrality with the loss of K. Electrophysiological studies showed that IC have a more predominant basolateral Cl conductance than PC (30, 32). Furthermore, C11 have a Cl conductance pathway involved in a volume-regulatory decrease (43). The predominant Cl conductance is the reason that IC possess a higher cell potential compared with PC (−36 mV basolateral side for the IC vs. −82 mV for the PC) (12, 30). Moreover, in high dietary K conditions, aldosterone increases substantially the lumen negative potential. The depolarized apical membrane potential of the IC leads to an increased electrochemical gradient for K exit and a higher open probability for BK, thereby decreasing the need for elevated [Ca2+]i (12).

The Na-sensitive intermediate potassium channel (IK) has been previously described in MDCK cells and found to activate after bending of the primary cilium (34). mRNA analysis showed that C11 also contains IK (Holtzclaw JD, unpublished observations). Thus a role for the IK in flow-induced K efflux in IC cannot be excluded. However, TEA is a weak inhibitor of IK, only showing complete inhibition at 25 mM (11). Furthermore, the inhibition of K efflux by BK-β4 siRNA strongly suggests a role for BK-αβ4.

Role of BK-β4 and Ca2+.

Silencing of BK-β4 in C11 by siRNA was never greater than 80%, with typical silencing in the 60–70% range. Nevertheless, BK-β4 siRNA clearly eliminated the τ-induced K loss. Time course studies showed that after transfection by siRNA, BK-β4 quickly recovered to near normal levels within 48–72 h (data not shown). The transient knockdown suggests that BK-β4 is actively recycled, can be quickly replenished, and infers that BK-β4 plays an active role in the physiology of C11.

The inhibition of the flow-induced K efflux by BK-β4 siRNA suggests a specific regulatory role for BK-β4 in C11, potentially enhancing the sensitivity of BK to τ. It is not understood how BK-β modulates the effects of τ on BK. However, it is somewhat surprising that τ-induced K efflux is dependent on BK-α/β4 because BK-β4 decreases the Ca2+ sensitivity of the BK-α pore at low to moderate [Ca2+]i and increases its Ca2+ sensitivity at [Ca2+]i levels >1 μM (44). Since one of the main responses of C11 to flow is a transient increase in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 8) (35), one would expect the BK-β4 to enhance the Ca2+ sensitivity in the <1 μM range of Ca2+. However, the BK-β4-subunit could be playing a protective role, requiring either sustained increases in [Ca2+]i and/or depolarization of the apical membrane potential as previously discussed before undergoing volume-regulatory K efflux. Indeed, BK-α/β has such a role in presynaptic termini, where it acts to dampen the action potential only after the large depolarizations and increases in [Ca2+]i that are required for transmitter exocytosis (3). Alternatively, BK-β could be the shear stress sensor, promoting the activation of BK in response to either τ or membrane stretch independently of Ca2+. Supporting this notion is the finding that stretch alone, in the absence of Ca2+, can activate the BK of ICs; therefore, the Ca2+ sensitivity of BK-α/β4 may not be an issue regarding the response of BK to τ (31).

C11 as sensors of shear stress.

The mechanism by which IC sense flow remains uncertain. However, the protrusion of IC into the lumen will position the IC to act as shear stress sensors. Bending of apical microplicae on IC have been postulated as potential mechanisms for sensing flow (7). Moreover, MDCK cells can produce a transient increase in [Ca2+]i in response to pressure pulses that are ATP dependent and independent of the primary cilia (36). TRPV4, a Ca2+ permeable channel, is a potential sensor for both flow and osmolar changes in mouse CCD (48) and is expressed in IC and C11 (personal observations). Furthermore, TRPV4 can form a local Ca2+ signaling complex with BK (6), and TRPV4 knockout mice have attenuated flow-induced K secretion (42).

Our data show that C11 cells respond to 10 dynes/cm2 with a transient increase in [Ca2+]i. The depolarized apical membrane potential of IC under high-flow conditions could lower the Ca activation threshold for BK-α/β4 to near peak [Ca2+]i levels. Studies with rabbit split-open or occluded CCD have shown an increase in [Ca2+]i in both PC and IC in response to flow (25, 47), which required external Ca and Ca from inositol trisphosphate-sensitive internal stores (25). The fast and transient increase in intracellular Ca in IC indicates that K loss via BK-α/β4 is fast after increases in tubular flow. We suspect that BK-α/β4 closes after the reduction of cell Ca to prevent additional K loss and volume reduction until the flow is reduced to a lower rate.

Summary.

The C11 clones of MDCK cells exhibit the specific BK-α/β4 formation as described for IC in vivo. As our previous observations for IC in vivo, the τ of high flow caused a reduction in C11 size that was blocked by low Ca, and pharmacological or molecular inhibitors of BK-α/β4. The BK-α/β4-mediated volume reduction of IC would be critical for increasing luminal diameter and lowering the resistance to high flow. The increased luminal diameter would result in enhanced K secretion by increasing the chemical gradient for K secretion via PC K channels. However, it remains to be determined whether a non-Na-K-ATPase active transporter resides in IC to drive sustained K secretion via BK-α/β4.

GRANTS

This project was funded by National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants RO1 DK071014 and RO1 DK73070 (to S. C. Sansom), a fellowship (0610059Z) from the American Heart Association-Heartland Affiliate (P. R. Grimm), and American Recovery and Reinvestment Act Grant 3R01 DK071014-03S1 (L. Liu).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Janice A. Taylor and James R. Talaska of the Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope Core Facility at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

The monoclonal antibody against BK-α was developed by and/or obtained from the University of California-Davis/National Institutes of Health (NIH) NeuroMab Facility, supported by NIH Grant U24-NS-050606 and maintained by the Department of Neurobiology, Physiology, and Behavior, College of Biological Sciences, University of California, Davis, CA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailey MA, Cantone A, Yan Q, MacGregor GG, Leng Q, Amorim JB, Wang T, Hebert SC, Giebisch G, Malnic G. Maxi-K channels contribute to urinary potassium excretion in the ROMK-deficient mouse model of type II Bartter's syndrome and in adaptation to a high-K diet. Kidney Int 70: 51–59, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolivar JJ, Cereijido M. Voltage and Ca2+-activated K+ channel in cultured epithelial cells (MDCK). J Membr Biol 97: 43–51, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner R, Chen QH, Vilaythong A, Toney GM, Noebels JL, Aldrich RW. BK channel [beta]4 subunit reduces dentate gyrus excitability and protects against temporal lobe seizures. Nat Neurosci 8: 1752–1759, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cai Z, Xin J, Pollock DM, Pollock JS. Shear stress-mediated NO production in inner medullary collecting duct cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F270–F274, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmines PK, Fowler BC, Bell PD. Segmentally distinct effects of depolarization on intracellular [Ca2+] in renal arterioles. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 265: F677–F685, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Earley S, Heppner TJ, Nelson MT, Brayden JE. TRPV4 forms a novel Ca2+ signaling complex with ryanodine receptors and BKCa channels. Circ Res 97: 1270–1279, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evan AP, Satlin LM, Gattone VH, Connors B, Schwartz GJ. Postnatal maturation of rabbit renal collecting duct. II. Morphological observations. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 261: F91–F107, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frindt G, Palmer LG. K+ secretion in the rat kidney: Na+ channel-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F389–F396, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frindt G, Palmer LG. Low-conductance K channels in apical membrane of rat cortical collecting tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 256: F143–F151, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gekle M, Wunsch S, Oberleithner H, Silbernagl S. Characterization of two MDCK-cell subtypes as a model system to study principal cell and intercalated cell properties. Pflügers Arch 428: 157–162, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghanshani S, Wulff H, Miller MJ, Rohm H, Neben A, Gutman GA, Cahalan MD, Chandy KG. Up-regulation of the IKCa1 potassium channel during T-cell activation. Molecular mechanism and functional consequences. J Biol Chem 275: 37137–37149, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray DA, Frindt G, Palmer LG. Quantification of K+ secretion through apical low-conductance K channels in the CCD. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F117–F126, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimm PR, Irsik DL, Liu L, Holtzclaw JD, Sansom SC. Role of BK-β1 in Na+ reabsorption by cortical collecting ducts of Na+-deprived mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F420–F428, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimm PR, Irsik DL, Settles DC, Holtzclaw JD, Sansom SC. Hypertension of Kcnmb1−/− is linked to deficient K secretion and aldosteronism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 11800–11805, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grimm PR, Foutz RM, Brenner R, Sansom SC. Identification and localization of BK-β subunits in the distal nephron of the mouse kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F350–F359, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 260: 3440–3450, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guan Z, Buckman SY, Baier LD, Morrison AR. IGF-I and insulin amplify IL-1β-induced nitric oxide and prostaglandin biosynthesis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 274: F673–F679, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammami S, Willumsen NJ, Olsen HL, Morera FJ, Latorre Rn, Klaerke DA. Cell volume and membrane stretch independently control K+ channel activity. J Physiol 587: 2225–2231, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holthofer H, Schulte BA, Pasternack G, Siegel GJ, Spicer SS. Three distinct cell populations in rat kidney collecting duct. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 253: C323–C328, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holtzclaw JD, Grimm PR, Sansom SC. Intercalated cell BK-alpha/beta4 channels modulate sodium and potassium handling during potassium adaptation. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 634–645, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SW, Wang W, Nielsen J, Praetorius J, Kwon TH, Knepper MA, Frøkiær J, Nielsen S. Increased expression and apical targeting of renal ENaC subunits in puromycin aminonucleoside-induced nephrotic syndrome in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F922–F935, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komlosi P, Fintha A, Bell PD. Unraveling the relationship between macula densa cell volume and luminal solute concentration/osmolality. Kidney Int 70: 865–871, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kottgen M, Buchholz B, Garcia-Gonzalez MA, Kotsis F, Fu X, Doerken M, Boehlke C, Steffl D, Tauber R, Wegierski T, Nitschke R, Suzuki M, Kramer-Zucker A, Germino GG, Watnick T, Prenen J, Nilius B, Kuehn EW, Walz G. TRPP2 and TRPV4 form a polymodal sensory channel complex. J Cell Biol 182: 437–447, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu W, Morimoto T, Woda C, Kleyman TR, Satlin LM. Ca2+ dependence of flow-stimulated K secretion in the mammalian cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F227–F235, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu W, Xu S, Woda C, Kim P, Weinbaum S, Satlin LM. Effect of flow and stretch on the [Ca2+]i response of principal and intercalated cells in cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F998–F1012, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu M, Wang T, Yan Q, Yang X, Dong K, Knepper MA, Wang W, Giebisch G, Shull GE, Hebert SC. Absence of small conductance K+ channel (SK) activity in apical membranes of thick ascending limb and cortical collecting duct in ROMK (Bartter's) knockout mice. J Biol Chem 277: 37881–37887, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma R, Smith S, Child A, Carmines PK, Sansom SC. Store-operated Ca2+ channels in human glomerular mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F954–F961, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macknight AD, Leaf A. Regulation of cellular volume. Physiol Rev 57: 510–573, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malnic G, Berliner RW, Giebisch G. Flow dependence of K+ secretion in cortical distal tubules of the rat. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 256: F932–F941, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muto S, Giebisch G, Sansom S. Effects of adrenalectomy on CCD: evidence for differential response of two cell types. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 253: F742–F752, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pacha J, Frindt G, Sackin H, Palmer LG. Apical maxi K channels in intercalated cells of CCT. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 261: F696–F705, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmer LG, Frindt G. High-conductance K channels in intercalated cells of the rat distal nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F966–F973, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pluznick JL, Wei P, Grimm PR, Sansom SC. BK-β1 subunit: immunolocalization in the mammalian connecting tubule and its role in the kaliuretic response to volume expansion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F846–F854, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Praetorius HA, Frokiaer J, Nielsen S, Spring KR. Bending the primary cilium opens Ca2+-sensitive intermediate-conductance K+ channels in MDCK cells. J Membr Biol 191: 193–200, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Praetorius HA, Spring KR. Bending the MDCK cell primary cilium increases intracellular calcium. J Membr Biol 184: 71–79, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Praetorius HA, Spring KR. A physiological view of the primary cilium. Annu Rev Physiol 67: 515–529, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ridderstrale Y, Kashgarian M, Koeppen B, Giebisch G, Stetson D, Ardito T, Stanton B. Morphological heterogeneity of the rabbit collecting duct. Kidney Int 34: 655–670, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rieg T, Vallon V, Sausbier M, Sausbier U, Kaissling B, Ruth P, Osswald H. The role of the BK channel in potassium homeostasis and flow-induced renal potassium excretion. Kidney Int 72: 566–573, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sabolic I, Herak-Kramberger CM, Breton S, Brown D. Na/K-ATPase in intercalated cells along the rat nephron revealed by antigen retrieval. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 913–922, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strange K. Volume regulation following Na+ pump inhibition in CCT principal cells: apical K+ loss. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 258: F732–F740, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taniguchi J, Imai M. Flow-dependent activation of maxi K+ channels in apical membrane of rabbit connecting tubule. J Membr Biol 164: 35–45, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taniguchi J, Tsuruoka S, Mizuno A, Sato J, Fujimura A, Suzuki M. TRPV4 as a flow sensor in flow-dependent K+ secretion from the cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F667–F673, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tararthuch AL, Fernandez R, Ramirez MA, Malnic G. Factors affecting ammonium uptake by C11 clone of MDCK cells. Pflügers Arch 445: 194–201, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang B, Rothberg BS, Brenner R. Mechanism of beta4 subunit modulation of BK channels. J Gen Physiol 127: 449–465, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X, Pluznick JL, Settles DC, Sansom SC. Association of VASP with TRPC4 in PKG-mediated inhibition of the store-operated calcium response in mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1768–F1776, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woda CB, Bragin A, Kleyman TR, Satlin LM. Flow-dependent K+ secretion in the cortical collecting duct is mediated by a maxi-K channel. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F786–F793, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woda CB, Leite M, Jr, Rohatgi R, Satlin LM. Effects of luminal flow and nucleotides on [Ca2+]i in rabbit cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F437–F446, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu L, Gao X, Brown RC, Heller S, O'Neil RG. Dual role of the TRPV4 channel as a sensor of flow and osmolality in renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1699–F1713, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wunsch S, Gekle M, Kersting U, Schuricht B, Oberleithner H. Phenotypically and karyotypically distinct Madin-Darby canine kidney cell clones respond differently to alkaline stress. J Cell Physiol 164: 164–171, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu C, Rossetti S, Jiang L, Harris PC, Brown-Glaberman U, Wandinger-Ness A, Bacallao R, Alper SL. Human ADPKD primary cyst epithelial cells with a novel, single codon deletion in the PKD1 gene exhibit defective ciliary polycystin localization and loss of flow-induced Ca2+ signaling. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F930–F945, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu C, Shmukler BE, Nishimura K, Kaczmarek E, Rossetti S, Harris PC, Wandinger-Ness A, Bacallao RL, Alper SL. Attenuated, flow-induced ATP release contributes to absence of flow-sensitive, purinergic Cai2+ signaling in human ADPKD cyst epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F1464–F1476, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu Q, Norman JT, Shrivastav S, Lucio-Cazana J, Kopp JB. In vitro models of TGF-β-induced fibrosis suitable for high-throughput screening of antifibrotic agents. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F631–F640, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]