Abstract

Psychological stress is known to attenuate body size and lean body mass. We tested the effects of 1, 3, or 7 days of two different models of psychological stress, 1 h of daily restraint stress (RS) or daily cage-switching stress (CS), on skeletal muscle size and atrophy-associated gene expression in mice. Thymus weights decreased in both RS and CS mice compared with unstressed controls, suggesting that both models activated the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Body mass was significantly decreased at all time points for both models of stress but was greater for RS than CS. Mass of the tibialis anterior (TA) and soleus (SOL) muscles was significantly decreased after 3 and 7 days of RS, but CS only significantly decreased SOL mass after 7 days. TA mRNA levels of the atrophy-associated genes myostatin (MSTN), atrogin-1, and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitory subunit p85α were all significantly increased relative to unstressed mice after 1 and 3 days of RS, and expression of MSTN and p85α mRNA remained elevated after 7 days of RS. Expression of muscle ring finger 1 was increased after 1 day of RS but returned to baseline at 3 and 7 days of RS. MSTN, atrogin-1, and p85α mRNA levels also significantly increased after 1 and 3 days of CS but atrogen-1 mRNA levels had resolved back to normal levels by 3 days and p85α with 7 days of CS. p21CIP mRNA levels were significantly decreased by 3 days of CS or RS. Finally, body mass was minimally affected, and muscle mass was completely unaffected by 3 days of RS in mice null for the MSTN gene, and MSTN inactivation attenuated the increase in atrogin-1 mRNA levels with 4 days of RS compared with wild-type mice. Together these data suggest that acute daily psychological stress induces atrophic gene expression and loss of muscle mass that appears to be MSTN dependent.

Keywords: restraint stress, atrogenes, tibialis anterior, soleus, fast twitch

psychological stress is a common aspect of daily life for many people. Severe or chronic stress has a number of adverse health outcomes, including suppression of the immune system, increased risk for cardiovascular events such as heart attack and stroke, and greater propensity for certain types of cancer and autoimmune diseases (14, 18, 49). In addition, stress can dramatically alter body composition in ways that can exacerbate these negative effects on overall health. Specifically, stress is often associated with an increase in visceral adiposity in both rodents and humans (5, 47, 48), resulting in shifts in circulating cytokine, hormone, fatty acid, and glucose levels that can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease (4).

Stress can also decrease lean body mass in both humans and rodents (6, 12, 20, 25). From a health perspective, stress-induced decreases in lean mass may have two major adverse outcomes. First, a decrease in lean mass may further contribute to the stress-induced adverse metabolic profile by decreasing substrate oxidation due to a reduction in the amount of metabolically active tissue, which may result in even greater energy storage in adipose tissue. Second, chronic psychological stress may increase susceptibility to musculoskeletal injury by creating smaller, weaker muscles less capable of producing and/or sustaining an equivalent level of force as an unstressed muscle, which could result in a muscle more susceptible to mechanical strain-induced damage during normal use (15).

The specific molecular mechanism(s) by which daily psychological stress results in decreased lean body mass remain poorly defined. Stress-induced changes in body composition are thought to be a consequence of both decreased food intake elicited by stress (50) and increases in the secretion of glucocorticoids by the adrenal glands as a result of heightened activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) (5). Food deprivation and glucocorticoid administration are each known to elicit specific changes in skeletal muscle gene expression consistent with muscle atrophy, including increased expression of myostatin (MSTN); of the inhibitory subunit of the progrowth phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase), p85α; and of the so-called “atrogenes,” the ubiquitin ligases muscle ring finger 1 (MuRF1) and atrogin-1 (17, 21, 22, 32, 33, 38, 40, 52). However, the specific effects of psychological stress on skeletal muscle size and gene expression remain unknown.

The aim of the present work was to determine the effects of acute, daily psychological stress on skeletal muscle size and gene expression and, because of its key role in regulating muscle atrophy (19, 36, 37, 43), to examine the effects of MSTN inactivation on the muscle changes due to stress. To this end, we examined the effects of two different models of psychological stress, 1 h of daily restraint stress (RS) and daily cage switching, on muscle mass and proatrophy gene expression in mice across three time points. Our data suggest that acute daily stress is associated with decreases in body mass and muscle mass and increases in expression of MSTN, p85α, MuRF1, and atrogin-1. Moreover, MSTN null mice were much less affected by 3 days of RS, supporting the hypothesis that the muscle atrophy in response to stress is mediated through MSTN-dependent signaling pathways.

METHODS

Experimental animals.

All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Colorado, Boulder, and complied with the guidelines of the American Physiological Society on the use of laboratory animals. Three-month-old male wild-type C57/black6j mice were obtained from our breeding colony in the Department of Integrative Physiology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, or were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Purchased mice were allowed to acclimate to the vivarium environment for 4 wk before the start of the study. MSTN null mice were kindly provided by Dr. Se-Jin Lee.

Experimental manipulations.

All studies were done between routine weekly cage changes so as to minimize the influence of this form of stress on the outcome measures. All studies, including stress manipulations and killings, were completed between 0900 and 1300 to minimize/control for diurnal increases in glucocorticoid release. Mice in each of the groups were placed in individual cages several weeks before the experiments and remained so for the duration of the experiments. For the RS studies, mice (n = 4–5/time point) were lightly anesthetized by placing them in a 1-liter chamber with isofluorane for <15 s and placed in a 50-ml conical tube in which numerous breathing holes had been made in the cone end, with another hole in the screw cap to allow the tail to exit. Anesthetization with inhaled anesthesia for up to 1 min has been shown to have minimal effects on corticosterone and other stress markers in rodents (11); nevertheless, because we did not have a group of mice that only received the anesthesia and not the restraint, it is possible that the brief exposure to anesthesia contributed to the stress response in the RS mice. Mice were placed in the tubes at 0900 for 1 h and then released. RS was carried out daily for 1, 3, or 7 days, and mice were killed 24 h after the last RS bout. For cage-switch stress (CS) (n = 4–5/time point), we used the procedure previously used by Lee et al. (30, 31). Briefly, each morning CS mice were weighed and then placed in a cage previously occupied by another CS mouse. Mice were rotated round-robin through as many other cages of other CS mice as the duration of the experiment (1, 3, or 7 days) and were killed 24 h after the last cage switch. Bedding in cages of CS was not changed during the study in an attempt to maximize the stress-related sensory stimuli (pheromones, urine, etc.) of prior CS mice occupants. Three groups of mice served as controls. First, a group of mice (n = 5) was killed the 1st day of the experiment and served as a baseline control (BC). A second group of mice (n = 4–5/time point) was weighed each morning but was not subjected to RS or cage switching to control for the stress of daily handling (handling control; HC). Finally, a third group (n = 4–5/time point) was placed in individual cages and was not handled for the duration of the experiment but was fed the same amount of food each night as was eaten by the RS group and was the eating control (EC). Food was weighed for the RS mice each morning, and the amount eaten was estimated by subtracting from the prior day's total; the RS group daily mean amount of food was then given to the EC mice the following day. All mice with the exception of the EC group were weighed daily until death.

At each time point, all four groups (RS, CS, HC, EC) were killed by brief (<15 s) exposure to inhaled anesthesia as described by Jones et al. (24) followed by decapitation. Mice from each group were killed in random order, and the tibialis anterior (TA), soleus (SOL), spleen, and thymus were surgically removed, weighed, and frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. The TA and SOL were chosen as representative fast-twitch and slow-twitch muscles from the hindlimb. In addition, trunk blood was collected following decapitation and allowed to sit on ice before centrifugation and collection of the serum, which was also stored at −80°C until use.

For the study on MSTN null mice, wild-type and MSTN null mice were weighed the day before the experiment and then were either left unhandled for the duration of the experiment (n = 4–5/genotype) or were exposed to daily RS for 3 days (n = 5/genotype). Twenty-four hours after the third bout of RS (24 h), mice were exposed to RS for an additional hour and then allowed to recover for 1 h before death. The TA and SOL muscles were dissected, weighed, and frozen, and blood was taken for analysis as described above.

Blood measures.

Serum corticosterone levels were determined by using a commercially available ELISA kit (Assay Designs). In addition, blood glucose levels were quantified from 2 μl of serum using a OneTouch Ultra glucometer (LifeScan).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

RNA was isolated from skeletal muscle samples using the Trizol method as described previously (1–3). The RT reaction was carried out using 0.5 μg of RNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit from Applied Biosystems and RNA-specific probes according to the manufacturer's protocol. Primer and probe sets for MSTN, atrogin-1, MuRF1, p85α, p21CIP, and β-actin were obtained from Applied Biosystems. All real-time PCR procedures were run in triplicate to control for variances in loading. In addition, a standard curve ranging from 10- to 0.001-μg dilutions of mouse TA cDNA was run in duplicate for every assay to produce a standard curve for quantification. All values are expressed as the mean of the triplicate measure for the mRNA species in question divided by the mean of the triplicate measure of β-actin for each sample.

Statistical analysis.

All in vivo studies represent n = 4–5 animals/condition, and all data from these studies are reported as means ± SE. Statistically significant differences in tissue mass, serum measures, or mRNA levels between the different conditions at each time point were determined by ANOVA and Fisher's post hoc test. Differences between wild-type and MSTN null mice were determined by an independent t-test. For all statistical tests, an alpha level of 0.05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

Effects of stress on body mass.

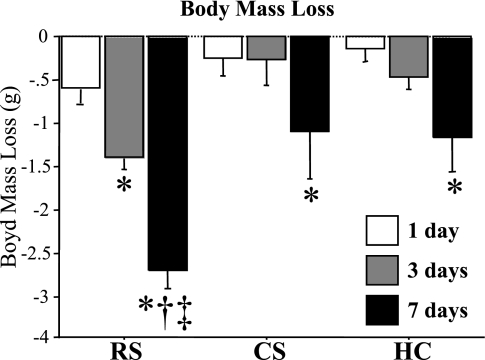

As shown in Fig. 1, the mean body mass lost by mice depended on both the experimental manipulation and its duration. RS mice lost an average of >0.5 g of body mass after 1 day of RS, and this significantly decreased further after both 3 and 7 days of RS (Fig. 1). RS mice lost significantly more mass at the 7-day time point than either CS or HC mice (Fig. 1). In contrast, CS mice lost <0.25 g after 1 day, slightly more after 3 days, and only with 7 days of CS did body mass significantly decrease further. Moreover, the loss in body mass in response to CS was similar to that lost by HC mice that were handled and weighed daily. The EC mice in this study were not weighed before the experiment so as to minimize handling stress, so it is not known to what extent body mass was affected by this manipulation. Moreover, this study did not have a condition where mice were unhandled but allowed ad libitum access to food, but in the subsequent study on wild-type and MSTN null mice described below, unstressed wild-type mice in this condition continued to gain weight over the first 4 days of the experiment (see Fig. 8A).

Fig. 1.

Body mass loss in response to acute daily stress. Body mass loss in grams for restrained (RS), cage-switched (CS), and handled and weighed (HC) mice after 1, 3, and 7 days. Body mass decreased for all 3 groups across the time line of the study, but RS resulted in the greatest decrease in body mass at each time point. Each bar represents the mean ± SE for n = 4–5 mice. P < 0.05, significantly different from 1-day time point (*), significantly different from 3-day time point (†), and significantly different from HC at the same time point (‡).

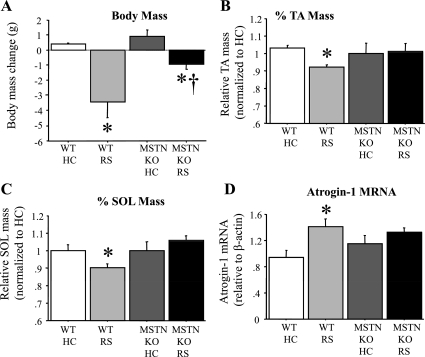

Fig. 8.

MSTN inactivation attenuates the changes with stress. A: body mass loss in grams of wild-type (WT) and MSTN null (MSTN KO) unstressed (HC) and stressed (RS) mice. Stress again resulted in a significant decrease in body mass in WT mice, whereas MSTN null mice loss significantly less mass than WT mice with stress. B: fraction of TA mass for WT and MSTN KO unstressed (HC) and stressed (RS) mice. The mean mass of unstressed WT or MSTN null mice was used to normalize the masses of stressed and unstressed mice so as to express them as a fraction. Stress significantly decreased TA mass relative to unstressed in the WT mice, but this decrease was abolished in the MSTN null mice. C: fraction of SOL mass for WT and MSTN KO unstressed (HC) and stressed (RS) mice. The mean mass of unstressed WT or MSTN null mice was used to normalize the masses of stressed and unstressed mice so as to express them as a fraction. Stress significantly decreased SOL mass relative to unstressed in the WT mice, but this decrease was abolished in the MSTN null mice. D: atrogin-1 mRNA expression relative to β-actin in the TA muscle of WT and MSTN KO unstressed (HC) and stressed (RS) mice. Stress significantly increased atrogin-1 mRNA relative to unstressed in the WT mice, but this increase was attenuated in the MSTN null mice. Bars in each panel represent means ± SE for n = 4–5 animals/group. P < 0.05, statistically significantly different from unstressed HC controls for that genotype (*) and significantly different from WT stressed mice values (†).

Effects of stress on spleen mass, thymus mass, and corticosterone levels.

Mean spleen mass after 1 day was significantly higher in the EC group than in the BC, HC, CS, and RS groups, although this likely reflected greater starting spleen mass in this group. Mean spleen mass did not significantly differ between any of the stressed groups and the BC group at 1 day but was significantly lower in the RS mice compared with the BC and EC mice after 3 days of daily RS (Table 1). At 7 days, there was again no significant difference between any of the groups in mean spleen mass (Table 1).

Table 1.

Spleen mass, thymus mass, and corticosterone levels for the stressed and unstressed mice

| BC | EC | HC | CS | RS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spleen mass, mg | |||||

| 1 Day | 69.4 ± 3.2† | 80.1 ± 4.0* | 66.4 ± 6.4† | 68.4 ± 2.3† | 69.5 ± 1.8† |

| 3 Days | 69.4 ± 3.2 | 70.5 ± 1.0 | 66.8 ± 1.3 | 67.7 ± 0.7 | 59.8 ± 2.0*† |

| 7 Days | 69.4 ± 3.2 | 71.3 ± 3.5 | 66.0 ± 3.9 | 66.5 ± 2.4 | 64.3 ± 2.3 |

| Thymus mass, mg | |||||

| 1 Day | 53.9 ± 3.2 | 37.5 ± 2.1* | 47.5 ± 1.6† | 42.4 ± 1.4* | 45.6 ± 0.8* |

| 3 Days | 53.9 ± 3.2 | 44.6 ± 4.6 | 38.4 ± 4.0* | 40.5 ± 4.5* | 35.8 ± 3.7* |

| 7 Days | 53.9 ± 3.2 | 37.6 ± 2.0* | 42.1 ± 3.2* | 36.6 ± 3.5* | 36.3 ± 4.4* |

| Plasma corticosterone, ng/ml | |||||

| 1 Day | 30.3 ± 4.0 | 30.3 ± 2.0 | 30.8 ± 2.0 | 31.1 ± 7.0 | 31.1 ± 4.0 |

| 3 Days | 30.3 ± 4.0 | 26.5 ± 7.0 | 43.6 ± 8.4 | 37.2 ± 4.8 | 36.2 ± 13.3 |

| 7 Days | 30.3 ± 4.0 | 35.2 ± 9.1 | 34.7 ± 4.1 | 26.1 ± 9.2 | 24.6 ± 6.5 |

Values shown are means ± SE BC, baseline control; EC, eating control; HC, handling control; CS, cage-switching stress; RS, restraint stress. The BC group was killed before the 1st day of the experiment and was the same for all time points. P < 0.05, significantly different from baseline (*) and significantly different from EC (†).

Mean thymus mass was significantly lower for the EC, RS, and CS mice compared with the BC mice after 1 day and remained lower for the CS and RS groups compared with the BC mice at 3 and 7 days (Table 1). In addition, thymus mass was also significantly lower for the HC group at the 3- and 7-day time points and for the EC mice at the 7-day time point (Table 1). There was no significant increase in serum corticosterone levels 24 h after the last stress bout in any group at any of the three time points, suggesting that the stress was an acute one not associated with sustained elevations in stress hormone levels (Table 1).

Effects of stress on muscle mass.

After a single bout of RS (1 day), TA mass was significantly different from BC, HC, and EC, but SOL mass was not significantly different from any other condition (Fig. 2, A and B). After 3 days of RS, mean TA and SOL mass were both significantly lower than that of BC, EC, HC, and CS mice (Fig. 2, C and D). Mean TA and SOL mass remained significantly lower for RS mice after 7 days relative to BC mice (Fig. 2, E and F). In contrast, TA mass was not affected by CS at any time point, and mean SOL mass was significantly lower in the CS group only at the 7-day time point compared with the BC group (Fig. 2F). Neither TA nor SOL mass was significantly different in the EC or HC groups compared with the BC group (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Tibialis anterior (TA) and soleus (SOL) mass are decreased by acute daily stress. Mean TA (A, C, and E) and SOL (B, D, and F) mass after 1 (A and B), 3 (C and D), or 7 (E and F) days. As described in methods, the conditions are baseline control (BC); eating control (EC), which was fed the same amount eaten as the RS mice; HC, which was handled and weighed each day like the RS and CS mice; RS; and CS. RS resulted in a significant decrease in TA at 1, 3, and 7 days and in SOL mass at 3 and 7 days, and CS resulted in a significant decrease in SOL mass at 7 days. Bars represent means ± SE for n = 4–5 mice/group. P < 0.05, significantly different from BC (*), significantly different from EC at the same time point (†), significantly different from HC at the same time point (‡), and significantly different from CS at the same time point (¥).

Atrophic gene expression is increased by stress.

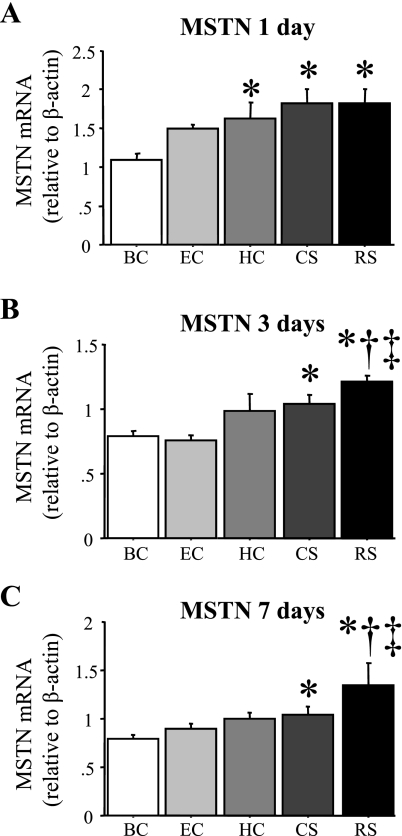

Expression of several proatrophy genes in the TA muscle showed small but significant increases 24 h after a single bout of acute stress relative to the BC group. MSTN mRNA levels were significantly increased by ∼75% over that of the BC group after 1 day of RS or CS (Fig. 3A) and remained modestly but significantly elevated after 3 and 7 days of RS or CS (Fig. 3, B and C). MSTN mRNA levels were also significantly increased after 1 day in the HC mice and tended to be higher after 3 days of daily handling and weighing though this was not significant (P = 0.0574) and were similar to BC after 7 days of daily handling (Fig. 3, A–C). Pair feeding also tended to elevate MSTN mRNA after 1 day (P = 0.0506), but MSTN mRNA levels from the EC mice were not significantly different from that of BC mice at 1, 3, or 7 days. MSTN mRNA levels were also significantly increased in the RS group at 1 and 3 days in the SOL muscle as well (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Myostatin (MSTN) mRNA levels are increased by acute daily stress. MSTN mRNA levels relative to β-actin in the TA muscle of the various groups after 1 (A), 3 (B), or 7 (C) days. MSTN mRNA levels significantly increased in the HC, CS, and RS groups after 1 day and in the CS and RS groups after 3 and 7 days. Bars in each panel represent means ± SE for n = 4–5 animals/group. P < 0.05, statistically significantly different from BC at the same time point (*), significantly different from EC at the same time point (†), and significantly different from HC at the same time point (‡).

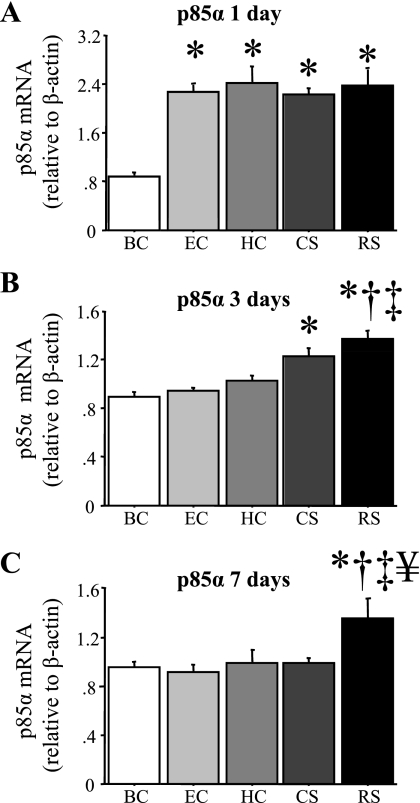

Expression of the PI 3-kinase inhibitory subunit p85α showed a similar pattern to MSTN but was even more robust. p85α mRNA levels significantly increased in all groups ∼2.5-fold after 1 day compared with the BC group, and remained elevated after 3 and 7 days of RS and after 3 days of CS relative to the BC group (Fig. 4, A–C). p85α mRNA levels were significantly greater in the RS group after 3 days than the EC, HC, and BC groups and were significantly greater in the RS group after 7 days than the CS, EC, HC, and BC groups (Fig. 4, B and C).

Fig. 4.

p85α mRNA levels are increased by acute daily stress. p85α mRNA levels relative to β-actin in the TA muscle of the various groups after 1 (A), 3 (B), or 7 (C) days. p85α mRNA levels significantly increased in the EC, HC, CS, and RS groups after 1 day, in the CS and RS groups after 3 days, and in the RS group after 7 days. Bars in each panel represent means ± SE for n = 4–5 animals/group. P < 0.05, statistically significantly different from BC at the same time point (*), significantly different from EC at the same time point (†), significantly different from HC at the same time point (‡), and significantly different from CS at the same time point (¥).

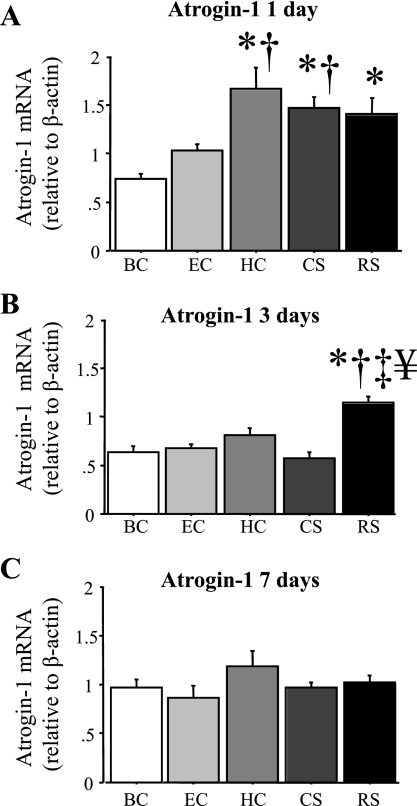

Atrogin-1 mRNA levels were also significantly elevated in response to various forms of stress. At 1 day, atrogin-1 mRNA levels were significantly increased by RS and CS and were also significantly increased in the HC mice relative to the BC mice at this time point (Fig. 5A). Atrogin-1 mRNA levels remained significantly elevated in the RS group after 3 days relative to the four other groups, but had returned to BC levels for all groups after 7 days (Fig. 5, B and C).

Fig. 5.

Atrogin-1 mRNA levels are increased by acute daily stress. Atrogin-1 mRNA levels relative to β-actin in the TA muscle of the various groups after 1 (A), 3 (B), or 7 (C) days. Atrogin-1 mRNA levels significantly increased in the HC, CS, and RS groups after 1 day and in the RS groups after 3 days but were not significantly different for any group after 7 days. Bars in each panel represent means ± SE for n = 4–5 animals/group. P < 0.05, statistically significantly different from BC at the same time point (*), significantly different from EC at the same time point (†), significantly different from HC at the same time point (‡), and significantly different from CS at the same time point (¥).

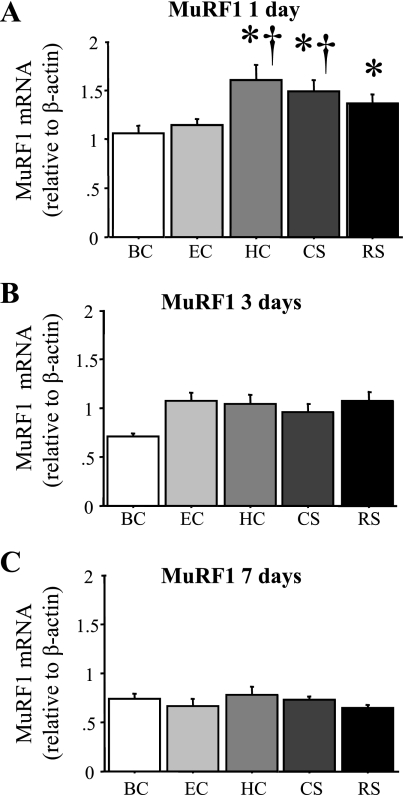

MuRF1 mRNA levels were significantly elevated 30–60% relative to the BC mice after 1 day of RS or CS and in the HC but not the EC mice (Fig. 6A) and were similar to the other conditions at the 3- or 7-day time points (Fig. 6, B and C).

Fig. 6.

Muscle ring finger 1 (MuRF1) mRNA levels are increased by acute daily stress. MuRF1 mRNA levels relative to β-actin in the TA muscle of the various groups after 1 (A), 3 (B), or 7 (C) days. MuRF1 mRNA levels significantly were increased in the HC, CS, and RS groups after 1 day but were not significantly different for any group after 3 or 7 days. Bars in each panel represent means ± SE for n = 4–5 animals/group. P < 0.05, statistically significantly different from BC at the same time point (*) and significantly different from EC at the same time point (†).

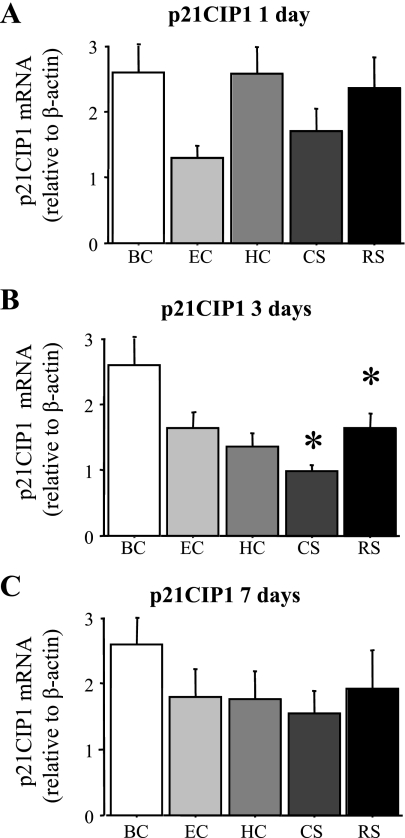

p21CIP1 mRNA levels were highly variable even in the BC mice and significantly decreased in the RS and CS groups at the 3-day time point but were similar among the other conditions and time points (Fig. 7, A–C).

Fig. 7.

p21CIP1 mRNA levels are increased by acute daily stress. p21CIP1 mRNA levels relative to β-actin in the TA muscle of the various groups after 1 (A), 3 (B), or 7 (C) days. p21CIP1 mRNA levels were not significantly different for any group after 1 or 7 days but significantly decreased in the CS and RS groups after 3 days relative to the BC. Bars in each panel represent means ± SE for n = 4–5 animals/group. *P < 0.05, statistically significantly different from BC at the same time point.

MSTN inactivation attenuates the changes with stress.

We then examined the role of MSTN in the stress-mediated changes observed above. Three days of RS again resulted in a significant decrease in body mass (Fig. 8A) and a small but significant decrease in TA (Fig. 8B) and SOL (Fig. 8C) mass in wild-type mice. However, in MSTN null mice, the decrease in body mass was significantly lower than that of wild-type mice, and the decreases in TA and SOL mass were completely abrogated (Fig. 8, A–C). Similarly, wild-type mice again showed a modest but significant increase in atrogin-1 mRNA levels with 3 days of RS, and this increase was attenuated in MSTN null mice such that atrogin-1 mRNA levels were not significantly different between the stressed and unstressed MSTN null mice (Fig. 8D).

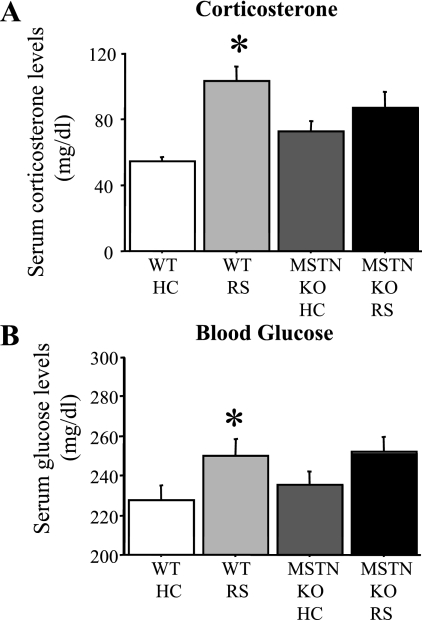

After a fourth and final bout of RS (1 h), we observed a significant two- to threefold increase in corticosterone levels in wild-type mice. However, MSTN null mice showed an attenuation in the increase in corticosterone levels with RS (Fig. 9A). In addition, stress is typically accompanied by an increase in blood glucose levels secondary to the increase in glucocorticoid secretion (33). Wild-type mice showed a small but significant hyperglycemia 1 h after a fourth and final daily bout of RS bout relative to unstressed mice, but MSTN mice showed a blunted hyperglycemic response in response to RS (Fig. 9B).

Fig. 9.

Corticosterone and blood glucose changes with stress are blunted in MSTN null mice. A: serum corticosterone levels of WT and MSTN KO unstressed (HC) and stressed (RS) mice. Serum corticosterone levels significantly increased 2- to 3-fold 1 h after the fourth of four daily RS bouts in WT mice relative to unstressed mice, but were not significantly different in stressed MSTN null mice compared with unstressed MSTN null mice. B: plasma glucose levels of WT and MSTN null (MSTN KO) unstressed (HS) and stressed (RS) mice. Plasma glucose levels significantly increased 1 h after the final four daily RS bouts in WT mice relative to unstressed mice, but were not significantly different in stressed MSTN null mice compared with unstressed MSTN null mice. Bars in each panel represent means ± SE for n = 4–5 animals/group. *P < 0.05, statistically significantly different from unstressed HC controls for that genotype.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we examined the effects of two different, previously characterized models of daily psychological stress, RS and CS, on muscle size and gene expression in mice. RS is a frequently used and well-characterized model for producing acute stress in rodents (7). This model causes a large transient increase in HPA axis activity and corticosterone release that has made it an excellent model for studying the consequences of elevated HPA activation on various output measures (7, 28, 29, 46). We observed significant decreases in spleen and thymus weights with RS at various time points throughout the study, two tissues known to be affected by stress and corticosterone levels (9, 24). We also observed no change in serum corticosterone levels 24 h after 1, 3, or 7 daily bouts of RS (Table 1), consistent with previous data demonstrating that the increase in HPA activation is transient and resolves within 1 day (29). Thus the RS regimen used in the present study appeared to result in a transient increase in glucocorticoid release consistent with acute HPA activation.

CS has also been used to elicit a stress response in rodents, but is not as well characterized as RS. Switching animals to a new unoccupied cage results in a two- to threefold increase in corticosterone levels within 15 min of the cage switch (54) and cardiovascular changes consistent with increased sympathetic activation (53). Switching to a cage previously occupied by another male mouse also produces cardiovascular changes consistent with increased sympathetic drive (10, 30, 31). In the present study, we were unable to measure serum corticosterone levels in the CS after cage switching since this would likely have caused as much as if not more stress than CS alone, but thymus mass was significantly lower in the CS mice than in the BCs at all time points, suggesting that these mice experienced some level of increased stress/corticosterone levels.

We chose CS as a second stress intervention because we felt it might provide a lower level and/or different temporal pattern of stress than that produced by RS. Some evidence suggests that this was the case, since the CS mice tended to have lower overall effects than RS mice on some of the outcome measures. For example, the loss in body mass in response to RS was significantly greater than that for CS at all time points (Fig. 1). Similarly, TA mass was unaffected by CS at any time point, and SOL mass was only affected after 7 days of daily CS (Fig. 2), whereas expression of p85α mRNA remained elevated at the 7-day time point for RS but not CS mice (Figs. 3 and 4). Together these data are consistent with the interpretation that CS produced lower overall effects on muscle than RS.

Interestingly, daily handling tended to increase proatrophy gene expression at the 1-day time point. However, handling stress alone was insufficient to induce changes in atrogene expression after 3 or 7 days while CS continued to produce significant effects after 3 days and RS continued to produce significant effects after 7 days. Nevertheless, these results underscore the sensitivity of mice to even mild stressors and emphasize the need to keep handling to a minimum before evaluation of atrogene expression and/or other markers sensitive to stress-induced activation of the HPA axis.

Our results are also consistent with the hypothesis that mice acclimate to daily stressors, particularly mild ones such as routine handling. The HC mice showed significantly higher levels of MSTN, p85α, atrogin-1, and MuRF1 1 day after a single bout of daily handling, but these were not significantly different at the 3- or 7-day time points. Moreover, even the RS mice showed some attenuation in the magnitude of atrogene expression across the time course of the study. Our data suggest that repeated exposure to the same stressor on multiple days does result in acclimation to the stressor, but they also suggest that the magnitude of the effect is gene-dependent, since the different atrophy-associated genes showed different temporal patterns of attenuation.

The results of the present study suggest that the effects of RS on the skeletal muscle parameters analyzed could not be explained by altered food/caloric intake alone. Food intake was significantly decreased in the HC, CS, and RS groups for the first 3 days of the study but were not significantly different from those of unstressed mice for days 4–6 [Supplemental Fig. 1 (Supplemental data for this article may be found on the American Journal of Physiology: Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology website.)]. Thus stress did result in a significant decrease in food intake during the earliest time points of the present study. However, food restriction alone had no significant effect on muscle mass or on atrogene mRNA levels at any time point and significantly increased MSTN and p85α mRNA levels at the 1-day time point only. In contrast, TA and SOL mass was significantly decreased after 3 and 7 days of RS, MSTN and p85α mRNA levels were significantly increased across all time points, and atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNA levels were elevated at several time points with RS. Thus RS produced much more robust effects on both gene expression and muscle mass than food restriction alone.

The exact stimuli eliciting the increase in atrophic gene expression were not identified in the present study. However, it is likely that most, if not all, of the changes observed with RS or CS were a consequence of the heightened activation of the HPA and/or sympathetic systems. Expression of MSTN, p85α, atrogin-1, and MuRF1 is directly regulated by glucocorticoids (17, 32, 33, 38, 40, 52), supporting the hypothesis that the elevation in the expression of these genes in response to RS or CS in the present study was a consequence of increased HPA activity resulting in increased systemic glucocorticoid levels. At present, there are no data supporting a link between increased sympathetic activity or blood catecholamine levels and proatrophy gene expression in skeletal muscle, although this does not preclude a contribution of this pathway to the increase in atrogene expression observed in the present study. Moreover, acute daily stress also causes disruption of other endocrine systems, and decreases both insulin and IGF-I secretion (26, 28), and these too may have contributed to the changes in atrogene expression reported here.

Because elevated glucocorticoids seemed to be a likely candidate for the increase in atrogene expression and decrease in muscle and body mass observed in the present study, and since a recent study suggested that MSTN expression is necessary for glucocorticoid-mediated muscle atrophy (16), we sought to determine whether MSTN was necessary for the stress-induced changes in muscle mass and atrogin-1 expression observed in the present study. Indeed, in the MSTN null mice subjected to RS, we found the increase in atrogin-1 mRNA was blunted, less body mass was lost, and muscle mass loss was completely abrogated (Fig. 8). At present, it is not clear whether the relative resistance of MSTN null mice to stress-induced changes in body mass, muscle mass, and gene expression is due to a direct role for MSTN in the skeletal muscle stress response or whether MSTN null mice are refractory due to developmental or other indirect compensatory consequences of MSTN inactivation. Arguing for the former is the fact that MSTN expression is increased by glucocorticoids (32, 33), and the fact that the increase in MSTN expression in another glucocorticoid-dependent model is attenuated by inhibition of glucocorticoid signaling with RU-486 (27). We recently demonstrated that MSTN null mice are similarly refractory to another model of glucocorticoid-mediated muscle atrophy, food deprivation (Allen DL, unpublished observations). Moreover, the fact that MSTN null mice are also resistant to glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy (16) is consistent with MSTN playing an intermediary role between HPA activation and muscle atrophy during daily stress.

One surprising finding of the present work was the fact that MSTN null mice appeared to experience an attenuated corticosterone response to stress. The reasons for this are unclear, but unstressed MSTN null mice tended to have higher serum corticosterone levels than unstressed wild type, although this was not significantly different from that of wild type. This modest elevation certainly contributed to the smaller difference in corticosterone levels between unstressed and stressed MSTN null mice. This may reflect a slightly greater need for glucocorticoid signaling in the basal, unstressed state of MSTN null mice, possibly as a compensatory mechanism for the loss in MSTN signaling to attenuate muscle size. Alternatively, the difference in unstressed corticosterone levels might simply be a methodological artifact: for reasons we were unable to determine, MSTN null mice experienced a much greater response to the light anesthesia required to incapacitate them for decapitation and typically required longer anesthesia times than wild-type mice, and this may have triggered a greater immediate HPA response before decapitation, which resulted in greater corticosterone levels in the “unstressed” state. Thus, at the present time, it is not clear whether a blunted corticosterone response to stress might have contributed to the attenuation in muscle atrophy with stress demonstrated by the MSTN null mice.

Both MSTN (23, 35, 39, 51) and p85α (17) are inhibitors of the PI 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) prohypertrophy cascade, and expression of both is increased by other modes of muscle atrophy, such as spaceflight unloading (3). Thus the increased expression of these genes in response to stress may result in reduced signaling flux through this critical growth-promoting pathway. Consistent with this, mRNA levels of atrogin-1 and MuRF1, genes whose expression is typically repressed by the PI 3-kinase/Akt cascade, were significantly increased in response to chronic acute psychological stress in the present study. This conclusion is also consistent with the results of Engelbrecht et al. (13) who demonstrated reduced Akt and forkhead box-O1 phosphorylation in the rat gastrocnemius muscle in response to 28 days of daily RS.

Weight loss is a well-documented consequence of acute daily psychological stress in mice and humans (6, 12, 20, 25), and studies have shown that lean carcass mass is also decremented by stress in rodents (12, 20). Consistent with our findings on muscle mass changes with acute stress are recent results by Engelbrecht et al. (13) who demonstrated that muscle fiber size in the gastrocnemius muscle was significantly decreased by 2 h of daily RS for 28 straight days. The decrease in muscle mass in the present study was not large; TA mass decreased ∼8–10% and SOL mass decreased ∼12% after 3 days of daily RS (Fig. 2). However, mass of the gastrocnemius/plantaris decreased ∼11% and mass of the SOL decreased ∼16% following 3 days of hindlimb suspension in mice (8), and thus the loss in mass in response to acute RS is actually similar in magnitude to the level of muscle mass lost with more traditional models of muscle atrophy such as hindlimb suspension.

Similarly, with the exception of the changes in p85α mRNA levels at the 1-day time point in the stressed mice, many of the changes in gene expression observed in the present study were fairly small, on the order of 1.3- to 2-fold changes. It is possible that some of these changes, although statistically significant, were not of sufficient magnitude to produce biologically meaningful changes in protein levels and thus muscle mass. This is certainly likely in the case of CS, in which we observed only modest effects on muscle mass. However, RS was associated with significant decreases in TA and SOL mass, which suggest that the modest changes in expression of these (and likely in other gene products not measured in this study) had a physiological effect on muscle size. This is further supported by the fact that MSTN inactivation attenuated the loss in muscle mass with RS even though MSTN mRNA levels increased at most less than twofold at any time point examined. It is also possible that changes in p85α and MSTN, as well as in other genes not analyzed, while small, may have additive effects on the signaling pathways regulating muscle growth and size. Future studies will need to evaluate the acute effects of daily stress on flux through pathways such as the PI 3-kinase/Akt/mTOR pathway to elucidate whether stress-induced gene expression changes affect growth signals within muscle.

The present study demonstrates that acute daily psychological stress is associated with muscle atrophy. Decreases in lean muscle mass may contribute to two adverse muscle-associated health outcomes of chronic stress in humans. First, decreases in lean muscle mass may contribute to a shift in body composition that can promote obesity. A loss in lean muscle mass decreases the amount of metabolically active tissue available for oxidative breakdown of energy substrate and decreases the primary platform for glucose uptake and thus may further contribute to the increased propensity of diabetes in stressed individuals (44, 45). In addition, a decrease in skeletal muscle mass in response to psychological stress may also predispose skeletal muscle to greater likelihood or severity of injury. Decreases in muscle mass and changes in fiber type (34) with stress result in a smaller, more fatigable muscle that could experience greater strain for a given level of contractile force, possibly increasing the likelihood of muscle damage (41, 42).

GRANTS

D. L. Allen was supported by National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Grant K01 AR-050505-01 for part of this work. In addition, this work was supported by an Innovative Seed Grant from the University of Colorado, Boulder. G. E. McCall was supported by a Mellon sabbatical grant from the University of Puget Sound.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen DL, Unterman TG. Regulation of myostatin expression and myoblast differentiation by FoxO and SMAD transcription factors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C188–C199, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen DL, Cleary AS, Speaker KJ, Lindsay SF, Uyenishi J, Reed JM, Madden MC, Mehan RS. Myostatin, activin receptor IIb, and follistatin-like-3 gene expression are altered in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle of obese mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 294: E918–E927, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen DL, Bandstra ER, Harrison BC, Thorng S, Stodieck LS, Kostenuik PJ, Morony S, Lacey DL, Hammond TG, Leinwand LL, Argraves WS, Bateman TA, Barth JL. Effects of spaceflight on murine skeletal muscle gene expression. J Appl Physiol 106: 582–595, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Björntorp P. Visceral fat accumulation: the missing link between psychosocial factors and cardiovascular disease? J Intern Med 230: 195–201, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bose M, Oliván B, Laferrère B. Stress and obesity: the role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in metabolic disease. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 16: 340–346, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branth S, Ronquist G, Stridsberg M, Hambraeus L, Kindgren E, Olsson R, Carlander D, Arnetz B. Development of abdominal fat and incipient metabolic syndrome in young healthy men exposed to long-term stress. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 17: 427–435, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buynitsky T, Mostofsky DI. Restraint stress in biobehavioral research: Recent developments. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 33: 1089–1098, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlson CJ, Booth FW, Gordon SE. Skeletal muscle myostatin mRNA expression is fiber-type specific and increases during hindlimb unloading. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 277: R601–R606, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chauhan PS, Satti NK, Suri KA, Amina M, Bani S. Stimulatory effects of cuminum cyminum and flavonoid glycoside on cyclosporine-A and restraint stress induced immune-suppression in Swiss albino mice. Chem Biol Interact 185: 66–72, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davern PJ, Chen D, Head GA, Chavez CA, Walther T, Mayorov DN. Role of angiotensin II Type 1A receptors in cardiovascular reactivity and neuronal activation after aversive stress in mice. Hypertension 54: 1262–1268, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Haan M, van Herck H, Tolboom JB, Beynen AC, Remie R. Endocrine stress response in jugular-vein cannulated rats upon multiple exposure to either diethyl-ether, halothane/O2/N2O or sham anaesthesia. Lab Anim 36: 105–114, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Depke M, Fusch G, Domanska G, Geffers R, Völker U, Schuett C, Kiank C. Hypermetabolic syndrome as a consequence of repeated psychological stress in mice. Endocrinology 149: 2714–2723, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engelbrecht AM, Smith C, Neethling I, Thomas M, Ellis B, Mattheyse M, Myburgh KH. Daily brief restraint stress alters signaling pathways and induces atrophy and apoptosis in rat skeletal muscle. Stress 13: 132–141, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Figueredo VM. The time has come for physicians to take notice: the impact of psychosocial stressors on the heart. Am J Med 122: 704–712, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finestone HM, Alfeeli A, Fisher WA. Stress-induced physiologic changes as a basis for the biopsychosocial model of chronic musculoskeletal pain: a new theory? Clin J Pain 24: 767–775, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilson H, Schakman O, Combaret L, Lause P, Grobet L, Attaix D, Ketelslegers JM, Thissen JP. Myostatin gene deletion prevents glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy. Endocrinology 148: 452–460, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giorgino F, Pedrini MT, Matera L, Smith RJ. Specific increase in p85alpha expression in response to dexamethasone is associated with inhibition of insulin-like growth factor-I stimulated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in cultured muscle cells. J Biol Chem 272: 7455–7463, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godbout JP, Glaser R. Stress-induced immune dysregulation: implications for wound healing, infectious disease and cancer. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 1: 421–427, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grobet L, Martin LJ, Poncelet D, Pirottin D, Brouwers B, Riquet J, Schoeberlein A, Dunner S, Menissier F, Massabanda J, Fries R, Hanset R, Georges M. A deletion in the bovine myostatin gene causes the double-muscled phenotype in cattle. Nat Genet 17: 71–74, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris RB, Zhou J, Youngblood BD, Rybkin II, Smagin GN, Ryan DH. Effect of repeated stress on body weight and body composition of rats fed low- and high-fat diets. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 275: R1928–R1938, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jagoe RT, Lecker SH, Gomes M, Goldberg AL. Patterns of gene expression in atrophying skeletal muscles: response to food deprivation. FASEB J 16: 1697–1712, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeanplong F, Bass JJ, Smith HK, Kirk SP, Kambadur R, Sharma M, Oldham JM. Prolonged underfeeding of sheep increases myostatin and myogenic regulatory factor Myf-5 in skeletal muscle while IGF-I and myogenin are repressed. J Endocrinol 176: 425–437, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ji M, Zhang Q, Ye J, Wang X, Yang W, Zhu D. Myostatin induces p300 degradation to silence cyclin D1 expression through the PI3K/PTEN/Akt pathway. Cell Signal 20: 1452–1458, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones BC, Sarrieau A, Reed CL, Azar MR, Mormède P. Contribution of sex and genetics to neuroendocrine adaptation to stress in mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology 23: 505–517, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kivimäki M, Head J, Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Brunner E, Vahtera J, Marmot MG. Work stress, weight gain and weight loss: evidence for bidirectional effects of job strain on body mass index in the Whitehall II study. Int J Obes (Lond) 30: 982–987, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohno H, Ohkubo Y. Comparative glucoregulatory responses of mice to restraint and footshock stress stimuli. Biol Pharm Bull 21: 113–116, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lang CH, Silvis C, Nystrom G, Frost RA. Regulation of myostatin by glucocorticoids after thermal injury. FASEB J 15: 1807–1809, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laugero KD, Moberg GP. Energetic response to repeated restraint stress in rapidly growing mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 279: E33–E43, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laugero KD, Moberg GP. Effects of acute behavioral stress and LPS-induced cytokine release on growth and energetics in mice. Physiol Behav 68: 415–422, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee DL, Webb RC, Brands MW. Sympathetic and angiotensin-dependent hypertension during cage-switch stress in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R1394–R1398, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee DL, Leite R, Fleming C, Pollock JS, Webb RC, Brands MW. Hypertensive response to acute stress is attenuated in interleukin-6 knockout mice. Hypertension 44: 259–263, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma K, Mallidis C, Artaza J, Taylor W, Gonzalez-Cadavid N, Bhasin S. Characterization of 5′-regulatory region of human myostatin gene: regulation by dexamethasone in vitro. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 281: E1128–E1136, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma K, Mallidis C, Bhasin S, Mahabadi V, Artaza J, Gonzalez-Cadavid N, Arias J, Salehian B. Glucocorticoid-induced skeletal muscle atrophy is associated with upregulation of myostatin gene expression. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 285: E363–E371, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martrette JM, Hartmann N, Westphal A, Favot L. Effect of glucocorticoid receptor ligands on myosin heavy chains expression in rat skeletal muscles during controllable stress. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 25: 297–302, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McFarlane C, Plummer E, Thomas M, Hennebry A, Ashby M, Ling N, Smith H, Sharma M, Kambadur R. Myostatin induces cachexia by activating the ubiquitin proteolytic system through an NF-kappaB-independent, FoxO1-dependent mechanism. J Cell Physiol 209: 501–514, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McPherron AC, Lee SJ. Double muscling in cattle due to mutations in the myostatin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 12457–12461, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McPherron AC, Lawler AM, Lee SJ. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta superfamily member. Nature 387: 83–90, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menconi M, Gonnella P, Petkova V, Lecker S, Hasselgren PO. Dexamethasone and corticosterone induce similar, but not identical, muscle wasting responses in cultured L6 and C2C12 myotubes. J Cell Biochem 105: 353–364, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morissette MR, Cook SA, Buranasombati C, Rosenberg MA, Rosenzweig A. Myostatin inhibits IGF-I-induced myotube hypertrophy through Akt. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 297: C1124–C1132, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishimura M, Mikura M, Hirasaka K, Okumura Y, Nikawa T, Kawano Y, Nakayama M, Ikeda M. Effects of dimethyl sulphoxide and dexamethasone on mRNA expression of myogenesis- and muscle proteolytic system-related genes in mouse myoblastic C2C12 cells. J Biochem 144: 717–724, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ploutz-Snyder LL, Tesch PA, Hather BM, Dudley GA. Vulnerability to dysfunction and muscle injury after unloading. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 77: 773–777, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riley DA, Thompson JL, Krippendorf BB, Slocum GR. Review of spaceflight and hindlimb suspension unloading induced sarcomere damage and repair. Basic Appl Myol 5: 139–145, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schuelke M, Wagner KR, Stolz LE, Hubner C, Riebel T, Komen W, Braun T, Tobin JF, Lee SJ. Myostatin mutation associated with gross muscle hypertrophy in a child. N Engl J Med 350: 2682–2688, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Surwit RS, Schneider MS, Feinglos MN. Stress and diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 15: 1413–1422, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Surwit RS, Schneider MS. Role of stress in the etiology and treatment of diabetes mellitus. Psychosom Med 55: 380–393, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swiergiel AH, Leskov IL, Dunn AJ. Effects of chronic and acute stressors and CRF on depression-like behavior in mice. Behav Brain Res 186: 32–40, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamashiro KL, Hegeman MA, Sakai RR. Chronic social stress in a changing dietary environment. Physiol Behav 89: 536–542, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamashiro KL, Hegeman MA, Nguyen MM, Melhorn SJ, Ma LY, Woods SC, Sakai RR. Dynamic body weight and body composition changes in response to subordination stress. Physiol Behav 91: 440–448, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thaker PH, Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK. The neuroendocrine impact of chronic stress on cancer. Cell Cycle 6: 430–433, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Torres SJ, Nowson CA. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition 23: 887–894, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trendelenburg AU, Meyer A, Rohner D, Boyle J, Hatakeyama S, Glass DJ. Myostatin reduces Akt/TORC1/p70S6K signaling, inhibiting myoblast differentiation and myotube size. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C1258–C1270, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waddell DS, Baehr LM, van den Brandt J, Johnsen SA, Reichardt HM, Furlow JD, Bodine SC. The glucocorticoid receptor and FOXO1 synergistically activate the skeletal muscle atrophy-associated MuRF1 gene. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E785–E797, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watanabe T, Hashimoto M, Okuyama S, Inagami T, Nakamura S. Effects of targeted disruption of the mouse angiotensin II type 2 receptor gene on stress-induced hyperthermia. J Physiol 515: 881–885, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wernstedt I, Edgley A, Berndtsson A, Fäldt J, Bergström G, Wallenius V, Jansson JO. Reduced stress- and cold-induced increase in energy expenditure in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R551–R557, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.