Abstract

This open, randomized phase I study evaluated the safety and reactogenicity of an experimental meningococcal serogroup B (MenB) vaccine obtained from outer membrane vesicle detoxified L3-derived lipooligosaccharide. Healthy young adults (n = 150) were randomized to receive either experimental vaccine (provided in five formulations, n = 25 in each group) or VA-Mengoc-BC (control, n = 25) administered on a 0- to 6-week/6-month schedule. Serum bactericidal assays performed against three MenB wild-type strains assessed the immune response, defined as a 4-fold increase from pre- to postvaccination. No serious adverse events related to vaccination were reported. Pain at the injection site, fatigue, and headache were the most commonly reported adverse events. Solicited adverse events graded level 3 (i.e., preventing daily activity) were pain (up to 17% of the test subjects versus 32% of the controls), fatigue (up to 12% of the test subjects versus 8% of the controls), and headache (up to 4% of any group). Swelling graded level 3 (greater than 50 mm) occurred in up to 4% of the test subjects versus 8% of the controls. The immune responses ranged from 5% to 36% across experimental vaccines for the L3 H44-76 strain (versus 27% for the control), from 0% to 11% for the L3 NZ98/124 strain (versus 23% for the control), and from 0% to 13% for the L2 760676 strain (versus 59% for the control). All geometric mean titers were below those measured with the control vaccine. The five experimental formulations were safe and well tolerated but tended to be less immunogenic than the control vaccine.

Meningococcal diseases caused by Neisseria meningitidis are a significant health burden throughout the world, leading to death and permanent sequelae (15). Whereas polysaccharide or polysaccharide conjugate vaccines are effective against serogroups A, C, Y, and W135, N. meningitidis serogroup B (MenB) remains a major cause of death and morbidity throughout the world, infants less than 1 year of age being affected the most (5, 8). Serogroup B outbreaks were reported in Europe, Latin America, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States (3, 7, 22, 33). Immunization against MenB presents a challenge, as the capsular polysaccharide is poorly immunogenic in humans (4) and shares molecular mimicry with human antigens (11), which guided the search for outer membrane vesicle (OMV) vaccines (16).

Three MenB OMV vaccines with PorA protein as the dominant antigen have been brought to the market (VA-Mengoc-BC [Finlay Institute], MeNZB [Chiron], and MenBvac [Norwegian Institute of Public Health]), but although they have shown protection against PorA-heterologous strains in older children and adults, protection of the youngest is mostly against PorA-homologous MenB strains and their accessibility is geographically limited (7, 9, 18, 21, 25, 26, 31, 34, 36, 37). To be immunogenic in the pediatric and adult populations, a more comprehensive MenB vaccine should include antigens inducing cross-reactive serum bactericidal antibodies (SBA) against a broad spectrum of circulating strains (16, 17, 20, 21, 35). That could best be achieved with non-PorA vaccines (20).

Natural immunity against MenB is also induced by protein and lipooligosaccharide (LOS) antigens (28), but proteins and LOS may vary substantially across meningococcal strains. However, at least 70% of invasive MenB isolates express LOS of immunotype L3,7 (19, 27, 29, 30). Hence, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) Biologicals has developed an experimental vaccine based on the LOS L3 immunotype that was shown to induce bactericidal antibodies in preclinical studies (39). Two detoxified LOS type 3 MenB experimental vaccines differing by the length of the LOS were developed. Such formulations have shown good safety and immunogenicity during preclinical and toxicological studies (39).

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the safety and reactogenicity of several formulations of the experimental vaccines given to healthy young adults. The secondary objective was to assess the immunogenicity of the different formulations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and ethical aspects.

Male and female young adults 18 to 25 years of age were recruited in Argentina (Centro de Educación Médica e Investigaciones Clínicas, Buenos Aires) after giving written informed consent. Subjects had to have completed routine childhood vaccinations (to the best of their knowledge) and to be free from obvious health problems. They were not admitted to the study if they had a history of or known exposure to meningococcal serogroup B disease or were previously immunized with meningococcal serogroup B vaccine. Any abnormal laboratory test value at screening, chronic drug administration, or planned administration of a vaccine not foreseen in the study protocol was a reason for nonenrolment. Acute disease or a temperature of ≥37.5°C at a vaccination visit resulted in postponement of vaccination or withdrawal from the study. Female subjects with childbearing potential had to agree to avoid pregnancy (by adequate contraceptive measures) and to have a negative pregnancy test before each vaccination.

This research was approved by the study center ethics committee and performed in compliance with the October 2000 version of the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use—Good Clinical Practice, and relevant institutional policies regarding the protection of human subjects. The clinical phase was carried out between April 2006 and June 2007.

Vaccine composition.

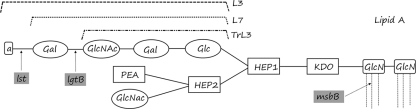

To increase the yield of the LOS present in the OMVs during the extraction phase, an optimized process was developed using 0.1% Na-deoxycholate. However, high levels of LOS are not acceptable for human vaccination due to the toxicity of the lipid A moiety. To circumvent that toxicity, we developed recombinant N. meningitidis strains harboring a detoxified lipid A by inactivating the msbB gene (Fig. 1) (39, 40).

FIG. 1.

Schematic structure of the LOS of N. meningitidis. L7 and TrL3 are both truncated forms of the L3 LOS; lst and lgtB are mutations of the LOS used to prepare the L7 and TrL3 epitopes; msbB is a mutation developed to detoxify the lipid A moiety; the tetrasaccharidic chain (lacto-N-neotetraose) is in bold (Gal-GlcNAc-Gal-Glc). a, sialic acid; Gal, galactose; Glc, glucose; GlcNac, N-acetylglucosamine; Hep, heptose; KDO, 2-keto-3-deoxyoctulosonic acid; PEA, phosphoethanolamine. Modified from reference 39.

Two genes, coding for the immunodominant and variable PorA and FrpB proteins, have been deleted to improve cross-protective immunogenicity induced by minor outer membrane proteins (39, 40). We overexpressed the minor proteins Hsf and TbpA by genetic manipulation (40, 41) and addition of an iron chelator to the culture medium.

Furthermore, to avoid the theoretical risk of autoimmunity, as human red blood cells and wild-type MenB LOS have the same lacto-N-neotetraose [LNnT] epitope (23), the tetrasaccharidic chain of the LOS has been genetically modified. Two different L3-derived immunogens were prepared, i.e., TrL3 and L7, differing by the saccharidic chain composition of the LOS. TrL3 is a truncated form of LOS missing the terminal sialic acid and galactose in the sugar structure, while L7 only lacks the terminal sialic acid (Fig. 1). TrL3 and L7 LOS were obtained by inactivation of the lst and lgtB genes (lst mutation and lgtB knockout), respectively (39, 40).

Vaccine formulation.

One dose (0.5 ml) of the experimental OMV vaccines contained (i) 4 μg of the truncated version of L3 (TrL3), for a protein content of about 25 μg, adsorbed to 50 μg of Al(OH)3, (ii) 8 μg of TrL3, for a protein content of about 50 μg, adsorbed (TrL3-8a) or not adsorbed (TrL3-8n) to 100 μg Al(OH)3, or (iii) 8 μg of L7, for a protein content of about 50 μg, adsorbed (L7-8a) or not adsorbed (L7-8n) to 100 μg Al(OH)3. The control vaccine was the Finlay Institute's VA-Mengoc-BC [50 μg OMV B:4:P1.15,19 with 50 μg meningococcal polysaccharide of serogroup C and 690 μg Al(OH)3].

Study design.

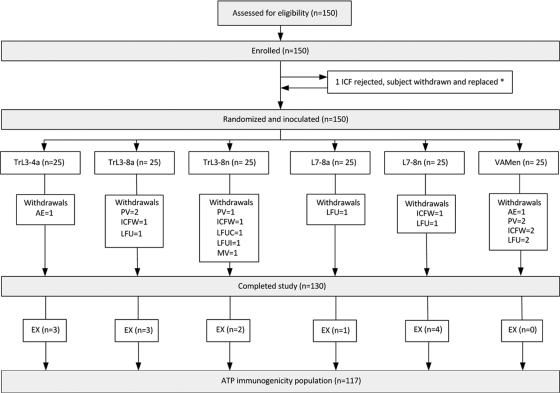

The study was randomized, open, and controlled with six study groups of 25 subjects each (Fig. 2). All subjects received three doses of vaccine on a 0- to 6-week/6-month schedule. The first five subjects of each group were enrolled and vaccinated stepwise with a safety review between steps; thereafter, full enrolment was pursued up to a total of 150 subjects. The randomization scheme was based on a minimization algorithm delivered through a central randomization system on the Internet.

FIG. 2.

Study flow chart. One hundred fifty subjects were randomized among five experimental formulations and a placebo. Group TrL3-4a (n = 25), TrL3 with 4 μg LOS (∼25 μg protein), adsorbed formulation; group TrL3-8a (n = 25), TrL3 with 8 μg LOS (∼50 μg protein), adsorbed formulation; group TrL3-8n (n = 25), TrL3 with 8 μg LOS (∼50 μg protein), nonadsorbed formulation; group L7-8a (n = 25), L7 with 8 μg LOS (∼50 μg protein), adsorbed formulation; group L7-8n (n = 25), L7 with 8 μg LOS (∼50 μg protein), nonadsorbed formulation; control group VAMen (n = 25), licensed VA-Mengoc-BC. AE, adverse event; EX, excluded from the analysis; ICFW, informed consent form withdrawn; LFUC, lost to follow-up with complete vaccination; LFUI, lost to follow-up with incomplete vaccination; MV, moved; PV, protocol violation. *, one informed consent form, signed by the subject's sister instead of the mother, led to the subject's withdrawal from the study, and the subject was replaced.

All vaccines were administered intramuscularly in the nondominant deltoid. Blood samples were collected from each subject before vaccination and 1 month after the second and third vaccinations for bactericidal assays, at screening and prior to and 2 and 7 days after each vaccine dose for safety tests (routine biochemistry and hematology), and at screening and prior to and 2 weeks after each vaccine dose for direct and indirect Coombs tests (Coombs tests were run on gel and, if positive, repeated and confirmed by the classical tube method). A urine sample was collected at screening and prior to and 2, 7, and 14 days after each vaccine dose for routine testing. Sera were stored at −20°C (or −70°C) until shipment to GSK Biologicals (Rixensart, Belgium) for serological assays; the other laboratory tests were performed at the study site laboratory. All study data were recorded via electronic case report forms.

Immunogenicity.

The immunogenicity of the study formulations was evaluated in the GSK Biologicals laboratory by standard methods with bactericidal antibody assays (SBA-MenB assays) using human complement. Serum samples were tested against three wild-type MenB strains (H44-76, B:15:P1.7,16:L3 [isolated in 1976 in Norway]; NZ98/124, B:4:P1.7,4:L3 [isolated in 1998 in New Zealand]; and 760676, B:2a:P1.5,2:L2 [isolated in 1976 in Netherlands]).

Safety monitoring.

All subjects were closely observed for at least 60 min after each vaccination. Reactogenicity data were collected from diary cards completed by the subjects during the 15 days following each vaccination (days 0 to 14). Solicited signs and symptoms included pain, redness, and swelling at the injection site, fatigue, fever, gastrointestinal symptoms, headache, and rash. Other (unsolicited) symptoms were recorded during the first 30 days after each vaccine dose. Abnormal biochemistry or hematology values were also recorded. All injection site reactions were considered related to vaccination; the causal relationship of other adverse events was assessed by the investigators according to clinical judgment. Adverse events were scored on a three-grade intensity scale. Grade 3 was assigned to symptoms preventing normal activity, to redness/swelling at the injection site >50 mm in diameter, and to a fever of >39.5°C (axillary route). All serious adverse events (SAEs; defined as hospitalization, disability, death, a life-threatening congenital anomaly, or an important medical condition) occurring from the first vaccine dose up to 1 month after the full vaccination course were also recorded. Pregnancies were recorded as SAEs and followed up to delivery.

Statistical analysis.

This phase I study was set up to get a preliminary safety assessment of a new MenB vaccine. A sample size of 25 subjects per group was selected to detect an increase in the percentage of subjects with grade 3 symptoms (solicited or unsolicited) following vaccination from 20% in the control group to 61% in a MenB group with 80% power (two-sided alpha = 5% unadjusted for multiple comparison). The safety and reactogenicity analyses were performed for the total vaccinated cohort. The incidence of solicited (local and general) symptoms within 4 and 14 days after each vaccination and unsolicited symptoms within 30 days after each vaccination was calculated along with the 95% confidence interval (CI). The occurrence of grade 3 symptoms within 4 and 14 days postvaccination was also calculated for each vaccine group along with the 95% CI.

The immunogenicity analysis was performed for the according-to-protocol (ATP) cohort (defined as all eligible subjects who received all three doses of vaccine according to their random assignments and in compliance with the protocol and for whom pre- and postvaccination results of at least one bactericidal assay were available) and for the total vaccinated cohort, as more than 5% of the subjects in most of the groups were eliminated from the ATP cohort for immunogenicity. The percentages of subjects with SBA-MenB titers of ≥1:2 and ≥1:4 and geometric mean titers (GMTs) of three antibodies (L3 H44-76, L3 NZ98/124, and L2 760676) were determined for each vaccine group along with the 95% CIs. The percentage of SBA-MenB responders in each vaccine group was also computed; vaccine response was defined as a postvaccination titer of ≥1:8 for subjects with a prevaccination titer of <1:2 and as a ≥4-fold increase over the prevaccination titer for initially seropositive subjects.

Antibody titers below the assay cutoff were given an arbitrary value of half the cutoff for the purpose of GMT calculation. Calculation of GMTs was performed by taking the antilog10 of the mean of the log10 concentration or titer transformations. Data analysis was performed at GSK Biologicals using SAS software (version 8.2) and StatXact (version 5.0); all analyses were descriptive only.

RESULTS

A total of 150 subjects 18 to 26 years old were enrolled and vaccinated with either the experimental or the control vaccine. Twenty subjects withdrew from the study for the reasons provided in Fig. 2, and 13 additional subjects were also excluded from the ATP analysis of immunogenicity. The demographic profiles of all of the groups were similar (Table 1). As the immunogenicity results obtained from the ATP cohort were consistent with those from the total vaccinated cohort, only data from the ATP cohort are presented here.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of vaccinated subjects in this studya

| Characteristic | TrL3-4a | TrL3-8a | TrL-8n | L7-8a | L7-8n | VAMen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. vaccinated | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| Mean age, yr (SD) | 21.6 (2.3) | 22.5 (2.0) | 21.8 (2.3) | 21.1 (2.6) | 22.2 (2.5) | 21.9 (2.2) |

| Female-to-male ratio | 19:6 | 12:13 | 7:18 | 15:10 | 11:14 | 13:12 |

TrL3-4a, TrL3 with 4 μg LOS, adsorbed formulation; TrL3-8a, TrL3 with 8 μg LOS, adsorbed formulation; TrL3-8n, TrL3 with 8 μg LOS, nonadsorbed formulation; L7-8a, L7 with 8 μg LOS, adsorbed formulation; L7-8n, L7 with 8 μg LOS, nonadsorbed formulation; VAMen, licensed VA-Mengoc-BC (control group).

Safety and reactogenicity.

A total of six SAEs were reported (one in each study group), none of them considered by the investigator to be related to vaccination; all except one (pregnancy leading to stillbirth) were resolved without sequelae. The administration of each formulation was comparable with regard to local and general solicited symptoms (Table 2). The vast majority of symptoms occurred in the first 4 days of the follow-up period. Pain at the injection site, fatigue, and headache were the most commonly reported solicited symptoms. Rash occurred, at most, after 3 (4%) doses of the experimental vaccine formulations (in three subjects) and after 3 (5%) doses of the control vaccine (in 3 subjects); there were no reports of petechiae or purpura.

TABLE 2.

Frequencies of local and systemic solicited symptoms over the three-dose vaccination coursea

| Symptom, typeb | No. (%) of subjects [95% CI] |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TrL3-4a (73 injected doses)e | TrL3-8a (69 injected doses) | TrL-8n (67 injected doses) | L7-8a (71 injected doses) | L7-8n (72 injected doses) | VAMen (63 injected doses) | |

| Pain | ||||||

| Any | 54 (75) [63-85] | 44 (64) [51-75] | 48 (72) [59-82] | 56 (79) [68-88] | 46 (64) [52-75] | 54 (86) [75-93] |

| Grade 3 | 1 (1) [0-8] | 1 (1) [0-8] | 1 (2) [0-8] | 4 (6) [2-14] | 4 (6) [2-14] | 13 (21) [12-33] |

| Redness | ||||||

| Any | 4 (6) [2-14] | 2 (3) [0-10] | 6 (9) [3-19] | 3 (4) [1-12] | 3 (4) [1-12] | 8 (13) [6-24] |

| >50 mm | 0 (0) [0-5] | 0 (0) [0-5] | 0 (0) [0-5] | 0 (0) [0-5] | 0 (0) [0-5] | 0 (0) [0-6] |

| Swelling | ||||||

| Any | 2 (3) [0-10] | 3 (4) [1-12] | 7 (10) [4-20] | 7 (10) [4-19] | 5 (7) [2-16] | 12 (19) [10-31] |

| >50 mm | 0 (0) [0-5] | 0 (0) [0-5] | 1 (2) [0-8] | 1 (1) [0-8] | 0 (0) [0-5] | 3 (5) [1-13] |

| Fatigue | ||||||

| Any | 26 (36) [25-48] | 23 (33) [22-46] | 21 (31) [21-44] | 26 (37) [26-49] | 26 (36) [25-48] | 26 (41) [29-54] |

| Grade 3 | 5 (7) [2-15] | 0 (0) [0-5] | 1 (2) [0-8] | 2 (3) [0-10] | 1 (1) [0-8] | 4 (6) [2-16] |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||||

| Any | 15 (21) [12-32] | 7 (10) [4-20] | 9 (13) [6-24] | 16 (23) [14-34] | 9 (13) [6-22] | 12 (19) [10-31] |

| Grade 3 | 1 (1) [0-7] | 0 (0) [0-5] | 0 (0) [0-5] | 1 (1) [0-8] | 0 (0) [0-5] | 0 (0) [0-6] |

| Headache | ||||||

| Any | 28 (38) [27-51] | 17 (25) [15-37] | 22 (33) [22-45] | 29 (41) [29-53] | 23 (32) [21-44] | 28 (44) [32-58] |

| Grade 3 | 2 (3) [0-10] | 0 (0) [0-5] | 1 (2) [0-8] | 1 (1) [0-8] | 1 (1) [0-8] | 3 (5) [1-13] |

| Feverc | ||||||

| Any | 6 (8) [3-17] | 9 (13) [6-23] | 3 (5) [1-13] | 9 (13) [6-23] | 7 (10) [4-19] | 9 (14) [7-25] |

| >39.5°C | 0 (0) [0-5] | 0 (0) [0-5] | 0 (0) [0-5] | 0 (0) [0-5] | 0 (0) [0-5] | 2 (3) [0-11] |

| Rash | ||||||

| Anyd | 3 (4) [1-12] | 2 (3) [0-10] | 0 (0) [0-5] | 2 (3) [0-10] | 1 (1) [0-8] | 3 (5) [1-13] |

| Grade 3 | 0 (0) [0-0] | 0 (0) [0-0] | 0 (0) [0-0] | 0 (0) [0-0] | 0 (0) [0-0] | 0 (0) [0-0] |

Symptoms were recorded during the 15-day period (days 0 to 14) following each vaccination. For study group compositions, see Table 1.

Symptoms were graded on a three-level intensity scale, grade 3 symptoms being defined as those preventing normal activity, redness/swelling >50 mm diameter, and a fever of >39.5°C.

Axillary temperature; fever was defined as a temperature of ≥37.5°C.

No petechiae or purpura reported.

n = 72 for pain, redness, and swelling in the TrL3-4a group.

Grade 3 solicited adverse events reported during the 14-day follow-up period were uncommon and within the same range across all of the groups, except for pain, which tended to occur less frequently after the experimental formulations (after 1 to 2% of the TrL3 doses [in one subject] and after 6% of the L7 doses [in up to four subjects]) than after the control vaccine doses (after 21% of the doses [in eight subjects]) (Table 2). A fever of ≥39.5°C was only observed in one subject after two of the three doses of VA-Mengoc-BC in the control group.

Laboratory test values were within the acceptable clinical range for all subjects. Direct Coombs tests were positive (1+ over a 3+ scale) for three subjects (by gel test, but results were negative when the classical tube method was used for confirmation). Those positive gel test results were considered probably false positive for one subject in the control group, as a repeat test done on the same day was negative. The two other subjects were in the TrL3-8n group. One subject turned positive on the basis of the blood sample collected the day of the second vaccine dose (i.e., 6 weeks after the first dose) and returned to normal on the basis of a subsequent blood sample collected 30 days later; a full investigation could not identify any etiology. The second subject presented a positive direct Coombs test that was considered probably related to antibiotics received to treat an earlier SAE (pneumonia). Both subjects were withdrawn from further vaccination.

Immunogenicity.

Prior to vaccination, the percentages of subjects with SBA-MenB titers of ≥1:4 against the three target strains were high: 94 to 100% for L3 H44-76, 100% for L3 NZ98/124, and 31 to 61% for L2 760676. One month after the third vaccine dose, all subjects had titers of ≥1:4 against L3 H44-76 and L3 NZ98/124. Approximately half of the subjects in the experimental groups and all except one subject in the control group had a titer of at least 1:4 against the L2 760676 strain. However, none of the five experimental formulations showed acceptable immunogenicity against any of the three strains tested, as GMTs did not increase significantly from pre- to postvaccination and all GMTs were below those obtained with the control vaccine (Table 3). Notably, we observed substantial immunogenicity against the L2 760676 strain with the control vaccine.

TABLE 3.

SBA GMTs by target straina

| Strain and timec | TrL3-4a |

TrL3-8a |

TrL-8n |

L7-8a |

L7-8n |

VAMen |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nb | GMT (95% CI) | n | GMT (95% CI) | n | GMT (95% CI) | n | GMT (95% CI) | n | GMT (95% CI) | n | GMT (95% CI) | |

| H44-76 | ||||||||||||

| Pre | 20 | 12.4 (7.8-19.7) | 17 | 11.6 (6.8-19.9) | 15 | 15.8 (9.2-26.9) | 23 | 14.9 (9.9-22.4) | 19 | 17.5 (9.5-32.3) | 18 | 18.4 (10.1-33.5) |

| Post II | 21 | 18.2 (13.1-25.3) | 18 | 17.8 (12.8-24.8) | 18 | 26.3 (17.0-40.8) | 23 | 27.4 (17.7-42.4) | 19 | 34.6 (18.6-64.3) | 17 | 49.1 (24.7-97.7) |

| Post III | 21 | 23.6 (15.6-35.8) | 18 | 22.7 (16.1-32.0) | 16 | 35.6 (19.9-63.8) | 22 | 37.9 (23.9-60.1) | 19 | 52.9 (27.5-101.6) | 15 | 92.7 (37.8-227.6) |

| NZ98/124 | ||||||||||||

| Pre | 20 | 46.1 (30.4-69.9) | 16 | 71.6 (45.2-113.2) | 18 | 59.6 (39.6-89.6) | 22 | 47.2 (30.1-74.0) | 18 | 60.3 (35.6-102.0) | 17 | 79.7 (46.8-135.9) |

| Post II | 20 | 61.0 (40.8-91.2) | 18 | 78.2 (54.1-113.1) | 18 | 66.2 (47.1-93.1) | 23 | 54.3 (39.9-73.9) | 19 | 61.3 (42.0-89.6) | 16 | 113.9 (67.0-193.6) |

| Post III | 21 | 53.2 (35.9-78.9) | 17 | 95.9 (69.3-132.6) | 16 | 67.1 (42.8-105.2) | 23 | 88.7 (60.7-129.6) | 19 | 83.0 (51.3-134.2) | 14 | 140.7 (62.4-317.3) |

| 760676 | ||||||||||||

| Pre | 20 | 3.5 (1.9-6.4) | 18 | 7.8 (3.2-19.2) | 16 | 2.9 (1.2-6.6) | 22 | 4.8 (2.5-9.4) | 18 | 2.8 (1.4-5.6) | 18 | 5.1 (2.4-10.8) |

| Post II | 20 | 3.1 (1.8-5.5) | 18 | 6.2 (2.5-15.1) | 17 | 1.5 (0.9-2.5) | 23 | 5.2 (2.4-11.2) | 19 | 3.9 (1.9-8.0) | 18 | 19.4 (10.9-34.5) |

| Post III | 21 | 3.6 (2.2-5.9) | 17 | 8.8 (3.6-21.4) | 15 | 3.0 (1.4-6.4) | 23 | 6.2 (3.0-12.9) | 19 | 4.2 (2.2-7.8) | 17 | 35.1 (19.9-61.9) |

For study group compositions, see Table 1.

Number of subjects whose antibody titers were available.

Pre, prior to vaccination; Post II, 1 month after second vaccination; Post III, 1 month after third vaccination.

The vaccine response (defined as a 4-fold increase in the SBA-MenB titer) 1 month after the last injection ranged in the experimental groups from 5 to 36% for the L3 H44-76 strain (versus 27% for the control group), from 0 to 11% for the L3 NZ98/124 strain (23% for the control), and from 0 to 13% for the L2 760676 strain (59% for the control) (Table 4). There was no obvious difference in the vaccine response (based on 95% CIs overlapping) between TrL3 and L7 or between the aluminum-adsorbed and nonadsorbed formulations.

TABLE 4.

Vaccine responses by target straina

| Strain | No. of subjects, response % (95% CI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TrL3-4a | TrL3-8a | TrL-8n | L7-8a | L7-8n | VAMen | |

| H44-76 | 20, 5.0 (0.1-24.9) | 17, 17.6 (3.8-43.4) | 13, 30.8 (9.1-61.4) | 22, 36.4 (17.2-59.3) | 19, 31.6 (12.6-56.6) | 15, 26.7 (7.8-55.1) |

| NZ98/124 | 20, 5.0 (0.1-24.9) | 15, 0.0 (0.0-21.8) | 16, 0.0 (0.0-20.6) | 22, 9.1 (1.1-29.2) | 18, 11.1 (1.4-34.7) | 13, 23.1 (5.0-53.8) |

| 760676 | 20, 0.0 (0.0-16.8) | 17, 5.9 (0.1-28.7) | 15, 13.3 (1.7-40.5) | 22, 4.5 (0.1-22.8) | 18, 5.6 (0.1-27.3) | 17, 58.8 (32.9-81.6) |

The vaccine response was defined as a ≥4-fold increase from pre- to postvaccination 1 month after the third injection. For study group compositions, see Table 1.

DISCUSSION

This study assessed five formulations of a MenB experimental vaccine expressing non-PorA, non-FrpB proteins and L3-derived LOS. Although safety and reactogenicity were acceptable, none of the experimental formulations induced sufficient immunogenicity to deserve further development.

Rather unexpected and in contrast to preclinical findings, where the experimental L3,7 formulations induced good immunogenicity in mice against the majority of L3,7 MenB strains (39), those results lead us to believe that murine Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and human TLR4 act differently. This is akin to recent findings reported by Steeghs et al. (32), who suggested that the msbB lipid A-LOS is a TLR4 agonist in mice but may act as a TLR4 antagonist in human. In our study, the msbB mutation curtailed immunogenicity in humans, which was not the case in mice. An ongoing clinical study performed by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research using detoxified OMV (also based on an msbB knockout strategy) (41) should allow us to confirm or not confirm the lower adjuvant effect of msbB LOS on human TLR4. Moreover, the slender immunogenicity profile could also result from the small amount or the absence of aluminum salt used in the experimental formulations, even if preclinical experiments demonstrated that nonadsorbed OMVs display an immunogenicity profile similar to that of adsorbed OMVs.

We observed prevaccination SBA-MenB titers (≥1:4 in more than 94% of our test subjects for the L3 strains and in 31 to 61% of our test subjects for the L2 strain) higher than those reported previously in United Kingdom adults (≥1:4 in more than 45% of the test subjects for L3 H44-76) (13) or in Belgian and Spanish adolescents (≥1:4 in 23 to 33% of the test subjects for L3 H44-76) (2). Our study was conducted with young adults, and it is well known that seropositivity spontaneously increases with age (12). However, high variability in SBA-MenB according to the complement sources and strains is not uncommon and was described by Findlow et al. (10), and differences between laboratories cannot be ruled out (1, 2). Another plausible explanation for the high prevaccination seropositivity seen could be the residual immunity conferred by MenB strains circulating in Argentina (6). Whatever the case, this pleads for relying on more than one type of assay to assess the predictive value of vaccine effectiveness (10, 38).

One limitation of our study was the exclusive use of SBA, particularly as it is a less sensitive measure than clinical efficacy, which can be achieved even with SBA titers of <1:4 (26, 38). Other mechanisms, such as opsonophagocytosis, are probably involved in clinical protection, as antibodies can be protective without being bactericidal (2, 26, 36). Moreover, Welsch and Granoff have reported bactericidal activity induced by whole blood in SBA-negative subjects, for some of them independently from white blood cells (14, 38).

Considering the very low immunogenicity observed with the experimental vaccines based on modified LNnT and in line with preclinical results (40), we can still hypothesize that the removal of the sialyl groups (in the TrL3 and L7 formulations) and the fourth sugar (in the TrL3 formulations) did not impact the antigenicity of the LOS molecule and the ability of induced antibodies to mediate the killing of L3 MenB strains.

A potential concern was the theoretical risk of induction of autoimmunity, due to the presence of the LNnT epitope on both MenB OMV and human erythrocytes. Although the experimental vaccine was genetically modified to prevent the expression of this LNnT epitope, Coombs tests (with a gel test as the primary test) were performed throughout this study as a precautionary measure. Three subjects had positive direct Coombs test results by this method, but none of them were confirmed by the classical tube method. There was a plausible etiology other than the vaccine for two subjects, but a possible relationship with vaccination could not be ruled out for one subject who was administered a TrL3 formulation, as no other plausible cause could be identified. Owing to the low immunogenicity of the vaccine, it is, however, highly improbable that the slightly positive gel test was induced by vaccine antibodies.

The Cuban VA-Mengoc-BC vaccine was chosen as a control since it was proven effective in subjects ≥4 years old, including against meningococcal B strains that are PorA heterologous to the vaccine (7, 24). In our study, VA-Mengoc-BC induced a weaker immune response (27%) than those observed in Iceland (44%) (26) and Chile (56%) (34) to the H44-76 strain, and reasonable explanations may be the high levels of preexisting antibodies in our study and differences in the assays or study populations used. Although the Cuban vaccine is made of OMV of the L3 immunotype, the response to the heterologous L2 strain (760676) was high in our study (59%); the absence of cross-reactivity between the L2 and L3 immunotypes (40) suggests that this cross-protective response is mediated by bactericidal antibodies directed against minor outer membrane proteins still to be identified, as the Cuban strain and the 760676 strain do not have homologous PorA and FrpB proteins.

The experimental vaccine has an acceptable safety profile, with fewer grade 3 symptoms (especially pain and signs of toxicity) than the control, supporting the benefit of LOS detoxification for the experimental formulations. The lower reactogenicity observed could also be the consequence of reduced aluminum content in the experimental vaccine or a combination of both factors.

In conclusion, the five experimental formulations were safe and well tolerated but tended to be less immunogenic than the control vaccine; hence, further clinical development of these candidate vaccines was stopped.

Acknowledgments

This study (number 105779) was sponsored by GSK Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium, which covered all costs.

We are grateful to all of the subjects who participated in this study, to Jean-Luc Liénard for drafting the manuscript, and to the health care personnel who helped carry out the study, including the collaborating physicians (María Fernanda Alsogaray, Eugenia Capetta, Fabián Herrera, Francisco Lossino, Analía Mykietiuk, Cristina Soler Riera, and Elena Temporiti). We also thank Tatjana Mijatovic for editorial assistance and Inke Bollens and Valérie Marichal for study management.

P. Bonvehí was the principal investigator in the studies funded by GSK. J. Casellas is a former employee of the GSK Group of Companies with ownership of stock options. J. Casellas is employed by Novartis Argentina. D. Boutriau, J. Casellas, C. Feron, J. Poolman, and V. Weynants are employees of the GSK Group of Companies. J. Poolman, J. Casellas, and D. Boutriau own stock options. J. Poolman, D. Boutriau, and V. Weynants are designated inventors in a variety of patents owned by GSK.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 July 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Borrow, R., I. S. Aaberge, G. F. Santos, T. L. Eudey, P. Oster, A. Glennie, J. Findlow, E. A. Hoiby, E. Rosenqvist, P. Balmer, and D. Martin. 2005. Interlaboratory standardization of the measurement of serum bactericidal activity by using human complement against meningococcal serogroup B, strain 44/76-SL, before and after vaccination with the Norwegian MenBvac outer membrane vesicle vaccine. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 12:970-976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boutriau, D., J. Poolman, R. Borrow, J. Findlow, J. D. Domingo, J. Puig-Barbera, J. M. Baldo, V. Planelles, A. Jubert, J. Colomer, A. Gil, K. Levie, A. D. Kervyn, V. Weynants, F. Dominguez, R. Barbera, and F. Sotolongo. 2007. Immunogenicity and safety of three doses of a bivalent (B:4:1.19,15 and B:4:1.7-2,4) meningococcal outer membrane vesicle vaccine in healthy adolescents. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 14:65-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bröker, M., and S. Fantoni. 2007. Meningococcal disease: a review on available vaccines and vaccines in development. Minerva Med. 98:575-589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruge, J., C. N. Bouveret-Le, B. Danve, G. Rougon, and D. Schulz. 2004. Clinical evaluation of a group B meningococcal N-propionylated polysaccharide conjugate vaccine in adult, male volunteers. Vaccine 22:1087-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cartwright, K. A. 2002. Epidemiology of meningococcal disease. Hosp. Med. 63:264-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiávetta, L., E. Chavez, A. Ruzic, M. Mollerach, and M. Regueira. 2007. Surveillance of Neisseria meningitidis in Argentina, 1993-2005: distribution of serogroups, serotypes and serosubtypes isolated from invasive disease. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 39:21-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Moraes, J. C., B. A. Perkins, M. C. Camargo, N. T. Hidalgo, H. A. Barbosa, C. T. Sacchi, I. M. Landgraf, V. L. Gattas, H. D. Vasconcelos, et al. 1992. Protective efficacy of a serogroup B meningococcal vaccine in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Lancet 340:1074-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dittmann, S. 2004. Meningococcal disease. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 129:2666-2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.du Châtelet, I. P., M. K. Taha, J. M. Alonso, C. Sesbouë, P. Rouaud, G. Berthelot, A. Perrocheau, and D. Levy-Bruhl. 2007. Response to an outbreak of meningococcal disease due to a B:14:P1.7,16 strain, Seine-Maritime district, Normandy, France. 9th Meeting of the European Monitoring Group on Meningococci.

- 10.Findlow, J., S. Taylor, A. Aase, R. Horton, R. Heyderman, J. Southern, N. Andrews, R. Barchha, E. Harrison, A. Lowe, E. Boxer, C. Heaton, P. Balmer, E. Kaczmarski, P. Oster, A. Gorringe, R. Borrow, and E. Miller. 2006. Comparison and correlation of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B immunologic assay results and human antibody responses following three doses of the Norwegian meningococcal outer membrane vesicle vaccine MenBvac. Infect. Immun. 74:4557-4565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finne, J., M. Leinonen, and P. H. Mäkelä. 1983. Antigenic similarities between brain components and bacteria causing meningitis. Implications for vaccine development and pathogenesis. Lancet 2:355-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldschneider, I., E. C. Gotschlich, and M. S. Artenstein. 1969. Human immunity to the meningococcus. I. The role of humoral antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 129:1307-1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorringe, A. R., S. Taylor, C. Brookes, M. Matheson, M. Finney, M. Kerr, M. Hudson, J. Findlow, R. Borrow, N. Andrews, G. Kafatos, C. Evans, and R. Read. 2009. Phase I safety and immunogenicity study of a candidate meningococcal disease vaccine based on Neisseria lactamica outer membrane vesicles. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:1113-1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Granoff, D. M. 2009. Relative importance of complement-mediated bactericidal and opsonic activity for protection against meningococcal disease. Vaccine 27(Suppl. 2):B117-B125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Granoff, D. M., L. H. Harrisson, and R. Borrow. 2008. Meningococcal vaccines, p. 399-434. In S. A. Plotkin, P. A. Offit, and W. A. Orenstein (ed.), Vaccines, 5th ed. W. B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, PA.

- 16.Holst, J. 2007. Strategies for development of universal vaccines against meningococcal serogroup B disease: the most promising options and the challenges evaluating them. Hum. Vaccin. 3:290-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holst, J., B. Fiering, L. M. Naess, G. Norheim, P. Kristiansen, E. A. Hoiby, K. Bryn, P. Oster, P. Costantino, M. K. Taha, J. M. Alonso, D. A. Caugant, E. Wedege, I. S. Aaberge, R. Rappuoli, and E. Rosenqvist. 2005. The concept of “tailor-made,” protein-based, outer membrane vesicle vaccines against meningococcal disease. Vaccine 23:2202-2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hosking, J., K. Rasanathan, F. C. Mow, C. Jackson, D. Martin, J. O'Hallahan, P. Oster, E. Ypma, S. Reid, I. Aaberge, S. Crengle, J. Stewart, and D. Lennon. 2007. Immunogenicity, reactogenicity, and safety of a P1.7b,4 strain-specific serogroup B meningococcal vaccine given to preteens. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 14:1393-1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones, D. M., R. Borrow, A. J. Fox, S. Gray, K. A. Cartwright, and J. T. Poolman. 1992. The lipooligosaccharide immunotype as a virulence determinant in Neisseria meningitidis. Microb. Pathog. 13:219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jordens, J. Z., J. N. Williams, G. R. Jones, M. Christodoulides, and J. E. Heckels. 2004. Development of immunity to serogroup B meningococci during carriage of Neisseria meningitidis in a cohort of university students. Infect. Immun. 72:6503-6510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy-Bruhl, D. 2006. Is there a need for a public vaccine production capacity at European level? Euro Surveill. 11:148-149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lingappa, J. R., N. Rosenstein, E. R. Zell, K. A. Shutt, A. Schuchat, and B. A. Perkins. 2001. Surveillance for meningococcal disease and strategies for use of conjugate meningococcal vaccines in the United States. Vaccine 19:4566-4575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandrell, R. E., J. M. Griffiss, and B. A. Macher. 1988. Lipooligosaccharides (LOS) of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis have components that are immunochemically similar to precursors of human blood group antigens. Carbohydrate sequence specificity of the mouse monoclonal antibodies that recognize crossreacting antigens on LOS and human erythrocytes. J. Exp. Med. 168:107-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noronha, C. P., C. J. Struchiner, and M. E. Halloran. 1995. Assessment of the direct effectiveness of BC meningococcal vaccine in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: a case-control study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 24:1050-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oster, P., D. Lennon, J. O'Hallahan, K. Mulholland, S. Reid, and D. Martin. 2005. MeNZB: a safe and highly immunogenic tailor-made vaccine against the New Zealand Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B disease epidemic strain. Vaccine 23:2191-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perkins, B. A., K. Jonsdottir, H. Briem, E. Griffiths, B. D. Plikaytis, E. A. Hoiby, E. Rosenqvist, J. Holst, H. Nokleby, F. Sotolongo, G. Sierra, H. C. Campa, G. M. Carlone, D. Williams, J. Dykes, D. Kapczynski, E. Tikhomirov, J. D. Wenger, and C. V. Broome. 1998. Immunogenicity of two efficacious outer membrane protein-based serogroup B meningococcal vaccines among young adults in Iceland. J. Infect. Dis. 177:683-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poolman, J., C. Hopman, and H. Zanen. 1980. Immunochemical characterization of Neisseria meningitidis serotype antigens by immunodiffusion and SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis immunoperoxidase techniques and the distribution of serotypes among cases and carriers. J. Gen. Microbiol. 116:465-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahman, M. M., C. M. Kahler, D. S. Stephens, and R. W. Carlson. 2001. The structure of the lipooligosaccharide (LOS) from the alpha-1,2-N-acetyl glucosamine transferase (rfaKNMB) mutant strain CMK1 of Neisseria meningitidis: implications for LOS inner core assembly and LOS-based vaccines. Glycobiology 11:703-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rune Andersen, S., J. Kolberg, E. A. Hoiby, E. Namork, D. A. Caugant, F. L. Oddvar, E. Jantzen, and G. Bjune. 1997. Lipopolysaccharide heterogeneity and escape mechanisms of Neisseria meningitidis: possible consequences for vaccine development. Microb. Pathog. 23:139-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scholten, R. J., B. Kuipers, H. A. Valkenburg, J. Dankert, W. D. Zollinger, and J. T. Poolman. 1994. Lipo-oligosaccharide immunotyping of Neisseria meningitidis by a whole-cell ELISA with monoclonal antibodies. J. Med. Microbiol. 41:236-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sierra, G. V., H. C. Campa, N. M. Varcacel, I. L. Garcia, P. L. Izquierdo, P. F. Sotolongo, G. V. Casanueva, C. O. Rico, C. R. Rodriguez, and M. H. Terry. 1991. Vaccine against group B Neisseria meningitidis: protection trial and mass vaccination results in Cuba. NIPH Ann. 14:195-207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steeghs, L., A. M. Keestra, A. van Mourik, H. Uronen-Hansson, P. van der Ley, R. Callard, N. Klein, and J. P. van Putten. 2008. Differential activation of human and mouse Toll-like receptor 4 by the adjuvant candidate LpxL1 of Neisseria meningitidis. Infect. Immun. 76:3801-3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taha, M. K., and J. M. Alonso. 2007. Meningococcal vaccines: to eradicate the disease, not the bacterium. Hum. Vaccin. 3:149-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tappero, J. W., R. Lagos, A. M. Ballesteros, B. Plikaytis, D. Williams, J. Dykes, L. L. Gheesling, G. M. Carlone, E. A. Hoiby, J. Holst, H. Nokleby, E. Rosenqvist, G. Sierra, C. Campa, F. Sotolongo, J. Vega, J. Garcia, P. Herrera, J. T. Poolman, and B. A. Perkins. 1999. Immunogenicity of 2 serogroup B outer-membrane protein meningococcal vaccines: a randomized controlled trial in Chile. JAMA 281:1520-1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vermont, C. L., G. P. van den Dobbelsteen, and R. de Groot. 2003. Recent developments in vaccines to prevent meningococcal serogroup B infections. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 5:33-38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vermont, C. L., H. H. van Dijken, A. J. Kuipers, C. J. van Limpt, W. C. Keijzers, A. van der Ende, R. de Groot, L. van Alphen, and G. P. van den Dobbelsteen. 2003. Cross-reactivity of antibodies against PorA after vaccination with a meningococcal B outer membrane vesicle vaccine. Infect. Immun. 71:1650-1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wedege, E., K. Bolstad, A. Aase, T. K. Herstad, L. McCallum, E. Rosenqvist, P. Oster, and D. Martin. 2007. Functional and specific antibody responses in adult volunteers in New Zealand who were given one of two different meningococcal serogroup B outer membrane vesicle vaccines. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 14:830-838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Welsch, J. A., and D. Granoff. 2007. Immunity to Neisseria meningitidis group B in adults despite lack of serum bactericidal antibody. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 14:1596-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weynants, V. E., P. Denoel, N. Devos, D. Janssens, C. Feron, K. Goraj, P. Momin, D. Monnom, C. Tans, A. Vandercammen, F. Wauters, and J. T. Poolman. 2009. Genetically modified L3,7 and L2 lipooligosaccharides from Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B confer a broad cross-bactericidal response. Infect. Immun. 77:2084-2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weynants, V. E., C. M. Feron, K. K. Goraj, M. P. Bos, P. A. Denoel, V. G. Verlant, J. Tommassen, I. R. Peak, R. C. Judd, M. P. Jennings, and J. T. Poolman. 2007. Additive and synergistic bactericidal activity of antibodies directed against minor outer membrane proteins of Neisseria meningitidis. Infect. Immun. 75:5434-5442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zollinger, W., M. Donets, B. Brandt, B. Ionin, E. Moran, D. Schmiel, V. Pinto, M. Fisseha, J. Labrie, R. Marques, and P. Keiser. 2008. Multivalent group B meningococcal vaccine based on native outer membrane vesicles (NOMV) has potential for providing safe, broadly protective immunity, abstr. O35, p. 51. Sixteenth International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference.