Abstract

The enzymatic activity of Bacillus subtilis glutamine synthetase (GS), which catalyzes the synthesis of glutamine from ammonium and glutamate, is regulated by glutamine feedback inhibition. The feedback-inhibited form of B. subtilis GS regulates the DNA-binding activities of the TnrA and GlnR nitrogen transcriptional factors. Bacterial GS proteins contain a flexible seven-residue loop, the Glu304 flap, that closes over the glutamate entrance to the active site. Amino acid substitutions in Glu304 flap residues were examined for their effects on gene regulation, enzymatic activity, and feedback inhibition. Substitutions in five of the Glu304 loop residues resulted in constitutive expression of both TnrA- and GlnR-regulated genes, indicating that this flap is important for regulating the activity of these transcription factors. The residues in the highly conserved Glu304 flap appear to be optimized for glutamate binding because mutant enzymes with substitutions in five of the flap residues had increased glutamate Km values compared to that for wild-type GS. The E304A and E304D substitutions increased the ammonium Km values compared to that for wild-type GS and conferred high-level resistance to inhibition by glutamine, glycine, and methionine sulfoximine. A model for the role of the Glu304 residue in glutamine feedback inhibition is proposed.

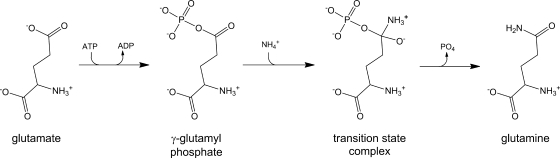

The ATP-dependent enzyme glutamine synthetase (GS) is the only known enzyme that is capable of the de novo synthesis of glutamine. Although GS is a metalloenzyme that can utilize Mg2+ or Mn2+ for in vitro catalytic activity, the Mg2+-dependent biosynthetic reaction is the physiologically relevant enzymatic activity (38, 46). The biosynthesis of glutamine involves the initial formation of γ-glutamyl phosphate from ATP and glutamate (Fig. 1) (33, 34). The second step involves the formation of a transition state complex that forms from a nucleophilic attack by ammonia on γ-glutamyl phosphate (Fig. 1). The subsequent release of phosphate results in the formation of glutamine.

FIG. 1.

Glutamine synthetase reaction mechanism.

Since glutamine is a key metabolite in nitrogen physiology, both the synthesis and the activity of GS are tightly regulated to maintain adequate glutamine levels for optimal growth. While low GS levels are found in cells growing rapidly with excess nitrogen, high GS levels are present in cells grown with limiting nitrogen. The enzymatic activity of GS is regulated by a variety of mechanisms. For instance, the Mg2+-dependent activity of GS from the low-G+C Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis is regulated by glutamine feedback inhibition (11). In contrast, the Mg2+-dependent activity of Escherichia coli GS is regulated by adenylylation, the covalent attachment of AMP to a specific tyrosine residue (38). The adenylylated form of the E. coli GS enzyme can be feedback inhibited by nine nitrogen-containing metabolites but not by glutamine (38, 43). It is not understood why the GS proteins from E. coli and B. subtilis have different sensitivities to feedback inhibition by glutamine.

While multiple GS isozymes are present in procaryotes (35), the most common bacterial GS enzyme, GSI, is a multimeric protein that contains 12 identical subunits arranged as two face-to-face hexameric rings (13). GSI enzymes have 12 active sites that are situated at the subunit interfaces within the hexameric rings. Each active site has a cylindrical structure where glutamate and ATP enter the active site from different ends of the cylinder (30). The only GS enzyme in B. subtilis is a GSI isozyme (40). Crystallographic studies of enzyme-ligand complexes for the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Mycobacterium tuberculosis GSI proteins suggest that the synthesis of glutamine involves a series of polypeptide loop and residue side-chain movements (13, 21). Of particular interest is a highly conserved 7-amino-acid-residue loop, the glutamate binding flap, which is located adjacent to the glutamate entrance to the active site. Because the position numbers of conserved residues are different for the GSI proteins from different organisms, the B. subtilis GS residue numbers are used exclusively in this report for clarity. The glutamate binding flap of B. subtilis GS corresponds to residues 300 to 306 and is called the Glu304 flap. The glutamate binding flap closes over the glutamate entrance to the active site and protects the unstable intermediates formed during the catalytic reaction from aberrant hydrolysis by water (13).

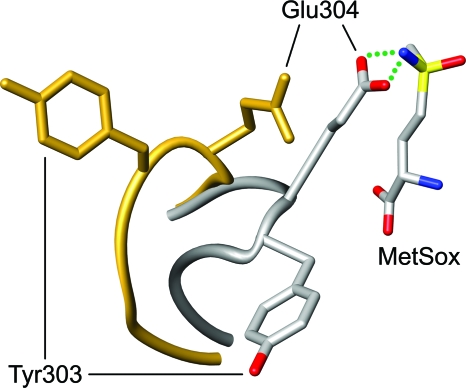

The GS inhibitor l-methionine-S-sulfoximine (MetSox) binds to the glutamate substrate site (30). In the presence of ATP, MetSox is phosphorylated by GS to form a transition state analogue that results in essentially irreversible inhibition of enzymatic activity (29, 42). Crystallographic studies of S. Typhimurium GS have shown that the binding of unphosphorylated MetSox induces the Glu304 flap to close over the entrance to the active site so that the side chain of the Glu304 residue interacts with MetSox (Fig. 2) (30). In contrast to its interaction with MetSox, the Glu304 residue of S. Typhimurium GS does not make contact with glutamine bound at the active site (30).

FIG. 2.

MetSox-induced structural changes in the Glu304 flap. The crystallographic models of S. Typhimurium GS in the presence (gray) and absence (gold) of MetSox are superimposed. The peptide backbones of the Glu304 flaps (residues 300 to 306) are depicted as smooth tubes. In the GS-MetSox complex, the residue side chains and MetSox are color coded by atom type: oxygen in red, nitrogen in blue, carbon in gray, and sulfur in yellow. B. subtilis GS residue Glu304 corresponds to S. Typhimurium GS residue Glu327. This figure was prepared with UCSF Chimera (37).

B. subtilis GS is a moonlighting protein which, in addition to its enzymatic function, has a critical role in the control of gene expression. Nitrogen regulation in B. subtilis is mediated by the TnrA and GlnR transcription factors (14). The feedback-inhibited form of GS (FBI-GS), which is present during growth with excess nitrogen, modulates the DNA-binding activities of TnrA and GlnR through direct protein-protein interactions. TnrA and GlnR are active under different nutritional growth conditions. GlnR is a transcriptional repressor that is functional in cells grown with excess nitrogen sources (7, 39). FBI-GS functions as a chaperone that activates GlnR by stabilizing GlnR-DNA complexes (17). TnrA activates and represses transcription during growth with limited nitrogen sources (4, 45, 48). FBI-GS forms a stable complex with TnrA that inhibits TnrA DNA-binding activity in cells grown with excess nitrogen (47). A previous study described two GS mutants with amino acid substitutions in the Glu304 flap, G302D and P306H, that were defective in regulating TnrA and GlnR (15). Since glutamine acts as a feedback inhibitor of B. subtilis GS by binding to the glutamate substrate site (16, 46), conformational changes in the Glu304 flap presumably occur during feedback inhibition. Taken together, these observations led to the proposal that TnrA and GlnR interact with the feedback-inhibited form of GS near the glutamate entrance to the active site (15, 16).

Although the Glu304 residue of E. coli GS has been examined in kinetic and mutagenic studies (1), the functions of the other residues in the Glu304 flap have not been similarly analyzed. In this report, amino acid substitutions in the Glu304 flap of B. subtilis GS were generated to examine the roles of Glu304 flap residues in enzymatic activity, feedback inhibition, and regulation of TnrA and GlnR activity. Characterization of the resulting mutant GS proteins demonstrated that the Glu304 flap plays a significant role in regulating the activity of TnrA and GlnR. Moreover, the Glu304 residue was found to be necessary for inhibition by glutamine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The B. subtilis strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Methods for the cultivation of bacteria in the minimal medium of Neidhardt et al. (36) have been described previously (3). All cultures contained 0.5% glucose and a nitrogen source with a concentration of 0.2%. Minimal medium agar plates were prepared as previously described (8). 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) was added to agar plates to give a final concentration of 40 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotypea | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| 168 | trpC2 | This laboratory |

| SF62 | tnrA62::Tn917trpC2 | 45 |

| SF218G | glnA(spc) trpC2 | 168 × pGLN218 |

| SF300 | amtB29::Tn917-lacZtrpC2 | 16 |

| SF300G7 | amtB29::Tn917-lacZ ΔglnA207::spctrpC2 | 16 |

| SF416 | amyE::((amtB-lacZ)416neo) trpC2 | 45 |

| SF416G11 | amyE::((amtB-lacZ)416neo) ΔglnA211::tettrpC2 | SF416 × pGLN211 |

| SF17 | amyE::((glnRA-lacZ)17neo) trpC2 | 45 |

| SF17G11 | amyE::((glnRA-lacZ)17neo) ΔglnA211::tettrpC2 | SF17 × pGLN211 |

| SF17G11T | amyE::((glnRA-lacZ)17neo) ΔglnA211::tettnrA62::Tn917trpC2 | SF17G11 × SF62 |

The amtB-glnK operon was formerly called nrgAB. The genotype symbols are described by Biaudet et al. (5).

Plasmids.

GS overexpression plasmids containing the mutant glnA genes were constructed as previously described (15). Plasmid pGLN211 is a clone of the glnRA region where the entire glnA coding sequence was replaced with a tetracycline resistance gene. The previously described pGLN206 plasmid contains DNA sequences from both the upstream and downstream regions adjacent to the B. subtilis glnA gene that were inserted into pJDC9 (9) and separated by a PstI restriction site (16). pGLN211 was constructed by inserting a tetracycline resistance gene cassette from pBEST309 (27) into the PstI site of pGLN206.

Plasmid pGLN218, which contains the glnRA region with a spectinomycin resistance gene inserted immediately downstream of the glnA gene, was constructed in three steps. A DNA fragment containing sequences located immediately downstream of the glnA gene was prepared by PCR amplification with primers GMCAAT32 and GMCHIN30 (Table 2) and inserted into pLEW424 (44) as an AatII-HindIII fragment to construct pGLN215. A DNA fragment containing the 3′ end of the glnR gene and the entire glnA gene was prepared by PCR amplification with primers GMCKPN32 and GMCAAT31 (Table 2) and inserted into pGLN215 as a KpnI-AatII fragment to give pGLN216. Plasmid pGLN218 was constructed by inserting a spectinomycin resistance gene cassette (22) into the AatII site of pGLN216.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | DNA sequence (5′ → 3′) | Location |

|---|---|---|

| GMCAAT31 | ATCTGACGTCGCCGCTCCATAATTTATTACC | 54 bp downstream of glnA |

| GMCAAT32 | TAGCGACGTCAATAAATTATGGAGCGGCACTG | 46 bp downstream of glnA |

| GMCBAM32 | TCGAGGATCCAGTTATCAGCAAGACAAATTCG | 380 bp upstream of glnA |

| GMCKPN32 | TCGAGGTACCAGTTATCAGCAAGACAAATTCG | 380 bp upstream of glnA |

| GMCUPS22 | AGTTATCAGCAAGACAAATTCG | 380 bp upstream of glnA |

| GMCHIN30 | ATCGAAGCTTTAAGAGTCATCTATAACCGC | 456 bp downstream of glnA |

| GMCXHO30 | ATGCCTCGAGTAAGAGTCATCTATAACCGC | 456 bp downstream of glnA |

| GMCDNS20 | TAAGAGTCATCTATAACCGC | 456 bp downstream of glnA |

Mutagenesis.

pGLN209 is an E. coli plasmid that contains the entire B. subtilis glnA gene and a neomycin resistance gene that is selectable in both E. coli and B. subtilis (16). Plasmid pGLN209 was mutagenized by propagation in the E. coli mutator strain XL1-Red (Stratagene). Strain SF300G7 (ΔglnA207::spc) was transformed with mutagenized pGLN209 DNA with selection for Gln on glucose minimal medium plates containing X-Gal and an excess nitrogen source (either ammonium chloride or glutamate plus ammonium chloride). Gln+ transformants that resulted from the integration of glnA into its chromosomal locus by a double-crossover event were identified by the absence of both plasmid-encoded neomycin resistance and chromosomal-encoded spectinomycin resistance. This mutant isolation procedure was different from previously described mutant hunts in that it involved localized mutagenesis of the glnA gene with a screen that was not biased for the isolation of mutants encoding feedback-resistant glnA mutations (15, 16).

Site-directed mutagenesis of glnA was performed by PCR overlap extension (26). In this method, the first set of amplifications utilizes complementary mutagenic primers to produce two DNA fragments with overlapping ends where the targeted mutation is located within the overlapping DNA sequence. PCR amplification with chromosomal DNA of strain SF218G as the template was used to generate a DNA fragment of the 5′ end of glnA with the upstream primer GMCUPS22 (Table 2) and one mutagenic primer. A DNA fragment of the 3′ end of glnA was produced with the downstream primer GMCDNS20 (Table 2) and the complementary mutagenic primer. The reaction products from these two amplifications were used as templates, together with primers GMCBAM32 and GMCXHO30 (Table 2), to generate a full-length glnA DNA fragment by PCR amplification. The final PCR product was cloned into the erythromycin-resistant plasmid pLEW424 as a BamHI-XhoI DNA fragment and subsequently sequenced to confirm the success of the mutagenesis. All of the mutant plasmids generated by this protocol have a spectinomycin resistance gene located immediately downstream of the glnA gene. To generate strains containing the mutant glnA genes and an amtB-lacZ fusion, mutant plasmid DNAs were used to transform strain SF416G11 (ΔglnA211::tet) with selection for spectinomycin resistance. Transformants that resulted from the integration of the mutant genes into the glnA chromosomal locus by a double-crossover event were identified by the absence of both plasmid-encoded erythromycin resistance and chromosomal-encoded tetracycline resistance. Chromosomal DNAs of the resulting strains were used to transform SF17G11T to obtain strains containing the mutant glnA genes and a glnRA-lacZ fusion.

Enzyme assays.

β-Galactosidase was assayed in crude extracts prepared from cells grown to mid-log growth phase as described previously (3). The reported β-galactosidase levels were corrected for the endogenous activity present in cells containing the promoterless lacZ fusion vectors integrated into the amyE gene. One unit of β-galactosidase activity produced 1 nmol of o-nitrophenol per min.

The specific activities of the biosynthetic and transferase GS reactions were determined as previously described (15). The kinetic constants for glutamate, ATP, and hydroxylamine were measured by assaying the production of γ-glutamylhydroxamate (46). The ammonium Km values were determined by measuring the production of inorganic phosphate that resulted from the hydrolysis of ATP (19). To minimize the effects of glutamine product inhibition, these assays were performed at 25°C and the reaction time was limited to 7.5 min. Assays to produce the ammonium saturation curves contained glutamate and ATP concentrations of 100 and 7.5 mM, respectively. The levels of inhibition of the Mg2+-dependent biosynthetic reaction by glutamine, AMP, and MetSox were determined with glutamate and ATP concentrations of 150 and 18 mM, respectively (46). Glycine inhibition of the Mn2+-dependent biosynthetic reaction was determined with glutamate and ATP concentrations of 100 and 7.5 mM, respectively.

Protein purification and analysis.

Overexpression and purification of TnrA and GS were performed as previously described (47). The purified proteins were greater than 98% homogeneous as judged by Coomassie blue staining of SDS protein gels. The conditions for the gel mobility shift assay used to analyze the DNA-binding activities of TnrA have been reported previously (47).

Protein modeling.

Although the crystal structure of the S. Typhimurium GS-MetSox complex has been determined (30), the atomic coordinates for this model are not present in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Therefore, the S. Typhimurium GS-phosphinothricin structure (PDB entry 1FPY) was used to model the GS-MetSox complex (20). Since MetSox and phosphinothricin are isosteric, the appropriate atoms in phosphinothricin were modified to give MetSox. As proposed by Gill and Eisenberg (20), the nitrogen atom of the MetSox sulfonimide group was oriented so that it was able to form a hydrogen bond with the carboxylate side chain of Glu304. To prepare Fig. 2, the native S. Typhimurium GS structure (PDB entry 1F52) was structurally aligned with the GS-MetSox complex.

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of glnA mutations.

Two different approaches were used to generate alterations in residues located in the Glu304 flap of glnA. In the first method, glnA mutations that resulted in constitutive TnrA regulation were isolated by localized mutagenesis of glnA followed by screening for constitutive expression of the TnrA-activated amtB-glnK operon. In this procedure, plasmid DNA containing the B. subtilis glnA gene was first mutagenized by propagation in an E. coli mutator strain. The mutagenized plasmid DNA was used to transform a glnA null mutant of B. subtilis with selection for Gln. This selection procedure requires all of the mutants to retain sufficient GS biosynthetic activity so that they can grow on medium that lacks glutamine. The B. subtilis strain contained a TnrA-activated amtB-lacZ fusion so that mutants with constitutive expression of the amtB promoter could be visualized as blue colonies on plates containing excess nitrogen and X-Gal, a chromogenic substrate for β-galactosidase. Sequence analysis identified seven different amino acid substitutions in the Glu304 flap (G302D, G302V, G302S, Y303H, Y303C, E304A, and E304D). Although six additional substitutions were also isolated (D27N, N34Y, L42P, F60L, D198N, and Q439R), these alterations were not located within the glutamate binding flap, and their characterization is not described in this communication.

To specifically evaluate the roles of all of the Glu304 flap residues, site-directed mutagenesis was used to generate additional amino acid substitutions in this protein loop. Residues Val300, Pro301, Gly302, and Pro306 were replaced with alanine. Tyr303 was mutated to phenylalanine, leucine, and alanine to provide a series of substitutions with decreasing side-chain sizes. Ala305 was replaced with glycine. All of the mutant glnA alleles were generated by site-directed mutagenesis and integrated into the chromosomal B. subtilis glnA locus.

When the growth properties of these mutants containing substitutions in the Glu304 flap were examined on plates containing glucose minimal medium, all of the strains exhibited normal growth with either glutamine or glutamate plus ammonium as the nitrogen source. Four of the glnA mutants (the Y303A, E304A, E304D, and A305G mutants) formed smaller colonies than the wild-type strain on glucose ammonium minimal medium plates. Because glutamate supplementation of the glucose ammonium minimal medium suppressed the growth defects seen with these four glnA mutants, the growth defects most likely result from the synthesis of GS proteins with partial enzymatic activity (see below). In addition, the strains encoding the E304A and E304D GS proteins were unable to grow on glucose minimal medium containing the limiting nitrogen source glutamate. This growth phenotype suggested that these mutant GS enzymes were defective in their ability to synthesize glutamine when cell growth is limited by ammonium availability (see below).

Regulation of TnrA and GlnR by the mutant GS proteins.

The effect of the GS amino acid substitutions on gene expression by a TnrA-activated amtB-lacZ fusion and GlnR-repressed glnRA-lacZ were examined in vivo (Table 3). Two of the GS mutants, the P301A and Y303F mutants, had no significant effect on TnrA- or GlnR-mediated regulation, and these glnA mutants were not studied further. The P306A mutant had partially constitutive glnRA-lacZ expression but had no effect on amtB-lacZ regulation. The in vivo regulation of both TnrA and GlnR was partially defective in three of the mutants (the V300A, G302A, and Y303H mutants). High-level constitutive expression of the amtB-lacZ and glnRA-lacZ fusions was observed with the remaining five mutants (the Y303A, Y303L, E304A, E304D, and A305G mutants). These results indicate that the Glu304 flap has an important role in the regulation of TnrA and GlnR by FBI-GS.

TABLE 3.

TnrA- and GlnR-dependent regulation in wild-type and glnA mutant strains

| glnA allele | Amino acid substitution | β-Galactosidase levela |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

amtB-lacZ fusion strain grown on: |

glnRA-lacZ fusion strain grown on: |

||||

| Glutamine | Glutamate | Glutamine | Glutamate | ||

| Wild type | 0.03 | 125 | 0.3 | 42 | |

| glnA(V300A) | Val300→Ala | 3.6 | 54 | 8.6 | 54 |

| glnA(P301A) | Pro301→Ala | 0.09 | 121 | 1.1 | 30 |

| glnA(G302A) | Gly302→Ala | 25 | 124 | 2.2 | 31 |

| glnA(Y303A) | Tyr303→Ala | 161 | 96 | 41 | 26 |

| glnA(Y303L) | Tyr303→Leu | 58 | 103 | 54 | 32 |

| glnA(Y303F) | Tyr303→Phe | 0.01 | 117 | 0.7 | 32 |

| glnA(Y303H) | Tyr303→His | 22 | 87 | 5.1 | 31 |

| glnA(E304A) | Glu304→Ala | 125 | NGb | 36 | NG |

| glnA(E304D) | Glu304→Asp | 115 | NG | 51 | NG |

| glnA(A305G) | Ala305→Gly | 39 | 47 | 30 | 22 |

| glnA(P306A) | Pro306→Ala | 0.01 | 60 | 4.5 | 23 |

All values are enzyme units per mg of protein and are the averages of the results from three or more determinations which did not vary by more than 20%. TnrA-dependent regulation was examined by determining β-galactosidase levels in cells containing the amtB416-lacZ fusion. GlnR-dependent regulation was examined by determining β-galactosidase levels in tnrA mutant cells containing the glnRA17-lacZ fusion. Cultures were grown in glucose minimal medium containing the indicated nitrogen sources. Glutamine is an excess nitrogen source, while glutamate is a limiting nitrogen source.

NG, no growth.

Enzymatic properties of the mutant enzymes.

To examine their biochemical properties, the nine mutant GS proteins defective in TnrA and GlnR regulation were overexpressed and purified to homogeneity. The specific activities for the Mg2+-dependent biosynthetic reaction, which is the major route for glutamine synthesis in vivo (38, 46), were determined for the enzymes (Table 4). In these in vitro assays, the substrate ammonium was replaced with hydroxylamine. This substitution circumvents the glutamine feedback inhibition of enzymatic activity that is present in the ammonium-dependent assay, because the product of the hydroxylamine-dependent reaction is γ-glutamylhydroxamate. Four of the mutant GS enzymes (the Y303A, E304A, E304D, and A305G mutants) had biosynthetic specific activities that were only 16 to 43% of the values obtained with the wild-type enzyme (Table 4). As noted previously, the glnA mutants that contained these four amino acid substitutions also grew poorly on glucose plus ammonium minimal medium. Taken together, these results argue that the poor growth of these mutant strains was most likely due to the inability of the mutant enzymes to synthesize sufficient glutamine to allow growth at wild-type rates on this medium.

TABLE 4.

Specific activities of wild-type and mutant GS enzymes

| GS enzyme | % sp act relative to wild-type levela |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mg2+-dependent biosynthetic reaction | Transferase reaction | |

| Wild type | 100 | 100 |

| V300A | 76 | 18 |

| G302A | 80 | 58 |

| Y303A | 36 | 8 |

| Y303L | 87 | 46 |

| Y303H | 150 | 100 |

| E304A | 43 | 5 |

| E304D | 37 | 8 |

| A305G | 16 | 2 |

| P306A | 160 | 130 |

The specific activities of wild-type GS for the Mg2+-dependent biosynthetic and transferase reactions were 3.8 and 98 μmol/min/mg, respectively. All values are the averages of two or more determinations. The standard errors were less than 20%.

The transferase assay is a partial reverse reaction in which GS catalyzes the synthesis of γ-glutamylhydroxamate from glutamine and hydroxylamine (12). Five of the mutant enzymes (the V300A, Y303A, E304A, E304D, and A305G mutants) had levels of transferase activity that were less than 20% of the value for the wild-type enzyme (Table 4).

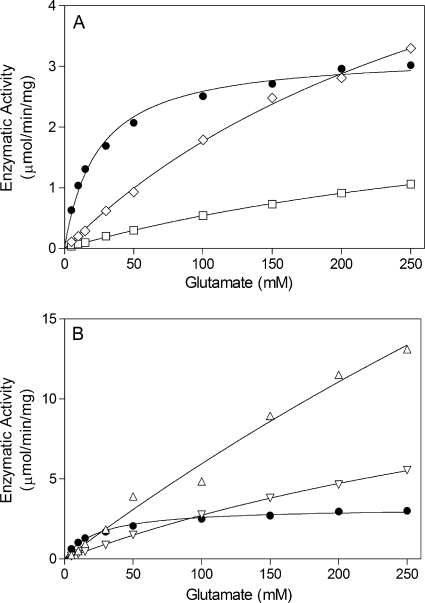

The steady-state kinetic constants for the physiologically relevant Mg2+-dependent biosynthetic reaction were also determined. The Vmax and Km values for glutamate could not be determined for five of the enzymes (the V300A, Y303A, Y303L, A305G, and P306A enzymes), because the substrate saturation curves were essentially linear in the range of glutamate concentrations used in the assays (Fig. 3). Nonetheless, these data indicate that these six enzymes have higher glutamate Km constants than wild-type GS. Compared to wild-type GS, the G302A and Y303H enzymes had only small differences (less than 4-fold) in their Km values for glutamate and ATP (Table 5). The E304A and E304D enzymes were the only mutant proteins that had glutamate Km values which were significantly lower than that for wild-type GS (Table 5). Interestingly, the E304A substitution decreased the ATP Km, while the E304D substitution had the opposite effect of increasing the ATP Km (Table 5). The observation that amino acid substitutions in the glutamate binding flap can alter the ATP Km suggests that there is an interdependent interaction between the glutamate and ATP binding sites.

FIG. 3.

Dependence of GS enzymatic activity on glutamate concentration for wild-type and mutant enzymes. The y axes for panels A and B are drawn to different scales. Symbols: •, wild type; ⋄, Y303A mutant; □, A305G mutant; ▵, P306A mutant; ▿, V300A mutant. The curve for the Y303L mutant (not shown) is similar to the curve for the V300A mutant.

TABLE 5.

Enzymatic constants for wild-type and mutant GS proteinsa

| Enzyme |

Km (mM) |

Vmax (μmol/min/mg) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamate | ATP | Ammonium | Hydroxylamine | ||

| Wild type | 27 ± 2 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 0.83 ± 0.07 | 3.7 ± 0.2 |

| G302A | 84 ± 11 | 5.3 ± 1.1 | NDb | ND | 3.6 ± 0.2 |

| Y303H | 59 ± 5 | 9.4 ± 1.6 | ND | ND | 12 ± 1 |

| E304A | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 32 ± 2 | 0.68 ± 0.09 | 1.3 ± 0.1 |

| E304D | 10 ± 1 | 11 ± 2 | 120 ± 10 | 0.74 ± 0.10 | 1.4 ± 0.1 |

The kinetic constants were determined for the Mg2+-dependent biosynthetic reaction. All assays were performed at least twice. The uncertainty is the standard error from the nonlinear regression analysis of the data.

ND, not determined.

Previous studies with E. coli GS showed that an E304A substitution increased the ammonium Km value (1). The E304A and E304D mutant enyzmes of B. subtilis GS were also found to have significantly higher ammonium Km values than the wild-type enzyme (Table 5). As noted previously, the B. subtilis mutants encoding the E304A and E304D mutant enzymes were unable to grow on glucose minimal medium containing the nitrogen source glutamate. Because ammonium availability is significantly restricted on this medium, the growth defect with these two mutants is most likely a direct consequence of the higher ammonium Km values of the E304A and E304D mutant enzymes.

Curiously, when the substrate ammonium was replaced with hydroxylamine in the Mg2+-dependent biosynthetic reaction of GS, the E304A and E304D enzymes were found to have hydroxylamine Km values that were similar to that for wild-type GS (Table 5). The implications of this difference between the ammonium and hydroxylamine Km values for these mutant enzymes are considered in the Discussion.

Sensitivities of the mutant enzymes to inhibitors.

Three of the mutant enzymes (the E304A, E304D, and A305G mutants) were highly resistant to feedback inhibition by glutamine (Table 6). Four of the mutant enzymes (the V300A, G302A, Y303A, and Y303L mutants) had moderately higher levels (3- to 8-fold) of resistance to glutamine inhibition (Table 6). The two mutant enzymes with Glu304 substitutions, the E304A and E304D mutants, had very high levels of resistance to inhibition by MetSox (Table 6). Although A305G GS was not as resistant to MetSox inhibition as the E304A and E304D enzymes, the A305G mutant GS had 20-fold higher resistance to inhibition by MetSox than wild-type GS (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Sensitivities of wild-type and mutant GS enzymes to inhibition

| Enzyme | IC50 (mM)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamine | AMP | MetSox | Glycine | |

| Wild type | 2.4 | 0.5 | 0.13 | 31 |

| V300A | 7.0 | 1.4 | 0.12 | NDb |

| G302A | 11 | 1.7 | 0.28 | ND |

| Y303A | 13 | 1.3 | 0.61 | ND |

| Y303L | 19 | 1.5 | 0.10 | ND |

| Y303H | 4.1 | 1.0 | 0.10 | ND |

| E304A | >140 | >30 | 26 | >800 |

| E304D | 79 | 1.7 | 20 | >800 |

| A305G | 140 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 350 |

| P306A | 1.5 | 0.2 | 0.25 | ND |

The IC50 is the inhibitor concentration that reduces enzymatic activity by 50%. The Mg2+-dependent biosynthetic assay was used to measure the inhibition by glutamine, AMP, and MetSox. Glycine inhibition was determined with the Mn2+-dependent biosynthetic assay. All values are the averages of at least two determinations. The standard errors were less than 10% for all values.

ND, not determined.

Glycine is a competitive inhibitor of S. Typhimurium GS that binds to the glutamate substrate site (32). The B. subtilis GS Mn2+-dependent biosynthetic reaction is inhibited by glycine (11). The three GS mutants that had high-level resistance to glutamine (the E304A, E304D, and A305G mutants) were also found to also have increased resistance to glycine inhibition (Table 6). AMP inhibits the Mg2+-dependent biosynthetic reaction of B. subtilis GS activity by binding to the ATP substrate site (11, 31). The E304A GS was the only mutant enzyme that had a significant increase in its resistance to AMP inhibition (Table 6). This result provides additional evidence for interdependence between the glutamate and ATP binding sites of GS.

In vitro regulation of TnrA by GS and MetSox.

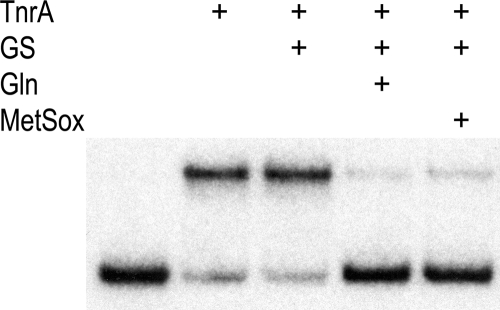

Although glutamine and MetSox both bind to the glutamate substrate site of GS, the Glu304 residue of S. Typhimurium GS hydrogen bonds with MetSox but does not interact with glutamine (16, 30, 46). In vitro experiments have shown that glutamine greatly enhances the ability of B. subtilis GS to inhibit the DNA-binding activity of TnrA (47). This result suggests that feedback-inhibited B. subtilis GS has a different conformation than uninhibited GS. To determine whether glutamine and MetSox induce similar conformational changes in B. subtilis GS, the abilities of these two compounds to stimulate the GS-mediated inhibition of TnrA DNA binding were examined in vitro. In these experiments, the binding of TnrA to the amtB promoter was monitored with a DNA gel mobility shift assay. As shown in Fig. 4, GS by itself does not alter the binding of TnrA to DNA. In contrast, when either glutamine or MetSox is present, GS is able to inhibit the DNA-binding activity of TnrA (Fig. 4). These results argue that the glutamine- and MetSox-bound forms of B. subtilis GS have similar conformations.

FIG. 4.

Abilities of glutamine and MetSox to promote the GS-mediated inhibition of TnrA DNA binding. A gel mobility shift assay was used to examine the binding of TnrA to amtB promoter DNA. The binding reaction mixtures contained TnrA (100 nM), GS (1 μM), glutamine (20 mM), and MetSox (20 mM), as indicated above the autoradiograph. ATP is not present in these binding mixtures, and thus MetSox is not phosphorylated.

DISCUSSION

The observation that the amino acid residues in the Glu304 flap from bacterial GSI proteins are highly conserved implies that the Glu304 flap has a common function in these enzymes. Since GS structural studies showed that this flap acts as a cover for the glutamate entrance to the active site, this flexible loop is likely to be involved in ligand binding to the active site (13). This idea is supported by our observations that amino acid substitutions in Glu304 flap residues of B. subtilis GS alter the glutamate Km values (Table 5; Fig. 3). These results argue that the residues in the Glu304 flap have been optimized during evolution for their role in GS enzymatic activity.

The E304A mutant enzymes of both B. subtilis and E. coli GS have higher ammonium Km values than their corresponding wild-type enzymes (Table 5) (1). These observations suggest that the Glu304 residues of B. subtilis and E. coli GS have the same catalytic role in the synthesis of glutamine. Crystallographic studies have shown that when the glutamate binding flap closes over the active site of GS, the Glu304 carboxylate side chain forms part of the ammonium substrate binding site (20, 21, 29). Thus, it is reasonable to assume that the E304A substitutions increase the ammonium Km values by directly reducing the mutant enzymes' affinities for ammonium. Although the E304A and E304D substitutions increase the ammonium Km values, they do not alter the hydroxylamine Km values (Table 5). This difference in effect on the substrate Km values is most likely a result of the different pKa values for these two substrates. While ammonia has a pKa value of 9.3, hydroxylamine has a significantly lower pKa value of 6.0 (6). Under the assay conditions used in these experiments, ammonium has a positive charge and needs a negatively charged pocket for optimal binding. In contrast, hydroxylamine is uncharged and thus the negatively charged side chain of Glu304 is not required for binding. In this scenario, removal of an amino acid side chain that contributes to the binding of a charged ammonium ion is expected to increase the observed ammonium Km value but to have no effect on the hydroxylamine Km value. Indeed, this behavior was obtained with the E304A and E304D GS substitutions (Table 5).

The B. subtilis Glu304 residue is required for glutamine feedback inhibition of GS (Table 6). The novelty of this observation is that although the corresponding glutamate residue is also present in E. coli GS, the E. coli enzyme is not feedback inhibited by glutamine (43). Therefore, the Glu304 residue is required but is not sufficient for glutamine inhibition, and additional protein residues must also contribute to the stable binding of glutamine to B. subtilis GS. Indeed, we have shown previously that amino acid substitutions in several B. subtilis GS active site residues can give rise to a feedback-resistant phenotype (16, 18, 46). Taken together, these results argue that multiple residues act together with Glu304 to stabilize feedback inhibitor binding to the active site. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that B. subtilis GS has evolved so that the conserved Glu304 residue has retained its role in catalysis while acquiring an additional function in glutamine feedback inhibition.

Several observations support the idea that glutamine and MetSox have equivalent interactions with B. subtilis GS. First, both of these compounds are inhibitors of GS that bind to the enzyme active site (30, 46). Second, amino acid substitutions of the Glu304 residue confer resistance to both of these inhibitors (Table 6). In addition, the observation that both glutamine and MetSox are able to promote the interaction between GS and TnrA (Fig. 4) suggests that glutamine and MetSox promote similar conformational changes in B. subtilis GS. The Glu304 side chain of B. subtilis GS may directly form a hydrogen bond with glutamine in a manner that is similar to the interaction observed between the S. Typhimurium Glu304 residue and MetSox (Fig. 2) (20, 30). Because the Glu304 residue of S. Typhimurium GS interacts with the sulfonimide nitrogen (Nɛ) of MetSox, it is tempting to speculate that the Glu304 residue of B. subtilis GS interacts with the analogous amide nitrogen (Nɛ) of glutamine. One shortcoming of this proposal is that glycine does not have a side chain that can interact with Glu304 and thus this model does not explain why glycine is able to promote the interaction between GS and TnrA (47) or why the E304A and E304D substitutions confer high-level resistance to glycine inhibition (Table 6). An alternative proposal consistent with all of our experimental observations is that the Glu304 side chain of B. subtilis GS interacts with the α-amino nitrogen of glutamine, glycine, and MetSox. A definitive explanation for the role of Glu304 in glutamine feedback inhibition of B. subtilis GS will require structural analysis of the feedback-inhibited enzyme.

The A305G mutant GS is similar to the enzymes with Glu304 substitutions in that it is resistant to inhibition by glutamine, MetSox, and glycine (Table 6). Since glycine residues in polypeptide chains have more conformational freedom than other amino acids, the replacement of Ala305 with glycine is expected to increase the local peptide backbone flexibility. This effect presumably alters the stability of the glutamate binding flap in A305G GS, and thus the A305G substitution most likely confers resistance to the inhibitors by indirectly affecting the adjacent Glu304 residue.

In addition to its catalytic functions, the Glu304 flap of B. subtilis GS plays a critical role in the regulation of TnrA and GlnR. Amino acid substitutions in five of the Glu304 flap residues resulted in mutant GS proteins unable to regulate the activity of these two transcription factors (Table 3). It is not known whether the Glu304 flap of FBI-GS directly interacts with TnrA and GlnR or whether the Glu304 flap participates in a GS conformational change that is required for the interaction of FBI-GS with TnrA and GlnR. This uncertainty means that it is unknown whether the Glu304 flap substitutions have a direct or indirect effect on the interaction of FBI-GS with TnrA and GlnR. Nonetheless, these data indicate that during evolution of the B. subtilis GS enzyme the Glu304 flap acquired a regulatory function while retaining its sequence conservation and role in glutamine synthesis.

Studies with animal model systems have shown that GS is required for the virulence of M. tuberculosis, S. Typhimurium, and Streptococcus pneumoniae (25, 28, 41). In addition, MetSox has been shown to inhibit the growth of M. tuberculosis in human mononuclear phagocytes, the bacterium's primary host cells, and in a guinea pig model of pulmonary tuberculosis (23, 24). While these studies demonstrate the potential of using GS as a drug target in antimicrobial therapy, specific mutants of GS can give rise to high-level MetSox resistance. For instance, the B. subtilis E304A and E304D mutant enzymes had levels of resistance to MetSox inhibition that were 200- and 150-fold higher, respectively, than that for wild-type GS (Table 6). This property is unique in that none of the previously isolated glutamine feedback-resistant B. subtilis GS enzymes had such high levels of resistance to MetSox inhibition (16, 18, 46). Studies with Anabaena azollae GS also showed that a mutant enzyme with a D54E amino acid substitution has high-level resistance to MetSox inhibition (10). Moreover, this Asp54 mutant had a growth defect in ammonium-limited medium similar to that seen for the B. subtilis Glu304 mutants (10). Although the biochemical mechanism for MetSox resistance of these mutant GS proteins is not known, it is interesting that the side chains of Asp54 and Glu304 are both part of a negatively charged pocket where ammonium binds to GS (1, 13). It is commonly observed that the acquisition of antibiotic resistance confers a reduction in fitness that is manifested as a decreased growth rate (2). Indeed, MetSox-resistant bacteria encoding mutant GS proteins with amino acid substitutions in the Asp54 or Glu304 residue have a conditional reduction in fitness in that these mutants have reduced growth rates on ammonium-limited medium (10). It is unclear whether this fitness reduction would affect the viability of pathogenic bacteria in their native hosts and thus preclude the emergence of MetSox-resistant strains.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Public Health Service grant GM051127 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 July 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alibhai, M., and J. J. Villafranca. 1994. Kinetic and mutagenic studies of the role of the active site residues Asp-50 and Glu-327 of Escherichia coli glutamine synthetase. Biochemistry 33:682-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson, D. I., and B. R. Levin. 1999. The biological cost of antibiotic resistance. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:489-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkinson, M. R., L. V. Wray, Jr., and S. H. Fisher. 1990. Regulation of histidine and proline degradation enzymes by amino acid availability in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 172:4758-4765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belitsky, B. R., L. V. Wray, Jr., S. H. Fisher, D. E. Bohannon, and A. L. Sonenshein. 2000. Role of TnrA in nitrogen source-dependent repression of Bacillus subtilis glutamate synthase gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 182:5939-5947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biaudet, V., F. Samson, C. Anagnostopoulos, S. D. Erlich, and P. Bessières. 1996. Computerized map of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 142:2669-2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bissot, T. C., R. W. Parry, and D. H. Campbell. 1957. The physical and chemical properties of the methylhyrdoxylamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 79:796-800. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, S. W., and A. L. Sonenshein. 1996. Autogenous regulation of the Bacillus subtilis glnRA operon. J. Bacteriol. 178:2450-2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chasin, L. A., and B. Magasanik. 1968. Induction and repression of the histidine-degrading enzymes of Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 243:5165-5178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, J. D., and D. A. Morrison. 1987. Cloning of Streptococcus pneumoniae DNA fragments in Escherichia coli requires vectors protected by strong transcriptional terminators. Gene 55:179-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crespo, J. L., M. G. Guerrero, and F. J. Florencio. 1999. Mutational analysis of Asp51 of Anabaena azollae glutamine synthetase. D51E mutation confers resistance to the active site inhibitors L-methionine-DL-sulfoximine and phosphinothricin. Eur. J. Biochem. 266:1202-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deuel, T. F., and S. Prusiner. 1974. Regulation of glutamine synthetase from Bacillus subtilis by divalent cations, feedback inhibitors, and L-glutamine. J. Biol. Chem. 249:257-264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deuel, T. F., and D. C. Turner. 1972. Bacillus subtilis glutamine synthetase. Dependence of γ-glutamyltransferase activity on ionic strength and specific monovalent cations. J. Biol. Chem. 247:3039-3047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenberg, D., H. S. Gill, G. M. U. Pfluegel, and S. H. Rotstein. 2000. Structure-function relationships of glutamine synthetases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1477:122-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher, S. H. 1999. Regulation of nitrogen metabolism in Bacillus subtilis: vive la différence! Mol. Microbiol. 32:223-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher, S. H., J. L. Brandenburg, and L. V. Wray, Jr. 2002. Mutations in Bacillus subtilis glutamine synthetase that block its interaction with transcription factor TnrA. Mol. Microbiol. 45:627-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher, S. H., and L. V. Wray, Jr. 2006. Feedback-resistant mutations in Bacillus subtilis glutamine synthetase are clustered in the active site. J. Bacteriol. 188:5966-5974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher, S. H., and L. V. Wray, Jr. 2008. Bacillus subtilis glutamine synthetase regulates its own synthesis by acting as a chaperone to stabilize GlnR-DNA complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:1014-1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher, S. H., and L. V. Wray, Jr. 2009. Novel trans-acting Bacillus subtilis glnA mutations that derepress glnRA expression. J. Bacteriol. 191:2485-2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gawronski, J. D., and D. R. Benson. 2004. Microtiter assay for glutamine synthetase biosynthetic activity using inorganic phosphate detection. Anal. Biochem. 327:114-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gill, H. S., and D. Eisenberg. 2001. The crystal structure of phosphinothricin in the active site of glutamine synthetase illuminates the mechanism of enzymatic inhibition. Biochemistry 40:1903-1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gill, H. S., G. M. U. Pfleugl, and D. Eisenberg. 2002. Multicopy crystallographic refinement of a relaxed glutamine synthetase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis highlights flexible loops in the enzymatic mechanism and its regulation. Biochemistry 41:9863-9872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guerout-Fleury, A. M., K. Shazand, N. Frandsen, and P. Stragier. 1995. Antibiotic-resistance cassettes for Bacillus subtilis. Gene 167:335-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harth, G., and M. A. Horwitz. 1999. An inhibitor of exported Mycobacterium tuberculosis glutamine synthetase selectively blocks the growth of pathogenic mycobacteria in axenic culture and in human monocytes: extracellular proteins as potential novel drug targets. J. Exp. Med. 189:1425-1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harth, G., and M. A. Horwitz. 2003. Inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis glutamine synthetase as a novel antibiotic strategy against tuberculosis: demonstration of efficacy in vivo. Infect. Immun. 71:456-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hendriksen, W. T., T. G. Kloosterman, H. J. Bootsma, S. Estevao, R. de Groot, O. P. Kuipers, and P. W. Hermans. 2008. Site-specific contributions of glutamine-dependent regulator GlnR and GlnR-regulated genes to virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 76:1230-1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho, S. N., H. D. Hunt, R. M. Horton, J. K. Pullen, and L. R. Pease. 1989. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77:51-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Itaya, M. 1992. Construction of a novel tetracycline resistance gene cassette useful as a marker on the Bacillus subtilis chromosome. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 56:685-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klose, K. E., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1997. Simultaneous prevention of glutamine synthesis and high-affinity transport attenuates Salmonella typhimurium virulence. Infect. Immun. 65:587-596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krajewski, W. W., T. A. Jones, and S. L. Mowbray. 2005. Structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis glutamine synthetase in complex with a transition-state mimic provides functional insights. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:10499-10504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liaw, S.-H., and D. Eisenberg. 1994. Structural model for the reaction mechanism of glutamine synthetase, based on five crystal structures of enzyme-substrate complexes. Biochemistry 33:675-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liaw, S.-H., G. Jun, and D. Eisenberg. 1994. Interactions of nucleotides with fully unadenylylated glutamine synthetase from Salmonella typhimurium. Biochemistry 33:11184-11188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liaw, S.-H., C. Pan, and D. Eisenberg. 1993. Feedback inhibition of fully unadenylylated glutamine synthetase from Salmonella typhimurium by glycine, alanine, and serine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:4996-5000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meek, T. D., and J. J. Villafranca. 1980. Kinetic mechanism of Escherichia coli glutamine synthetase. Biochemistry 19:5513-5519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meister, A. 1980. Catalytic mechanism of glutamine synthetase: overview of glutamine metabolism, p. 1-40. In R. Palacios and J. Mora (ed.), Glutamine: metabolism, enzymology, and regulation of glutamine metabolism. Academic Press, New York, NY.

- 35.Merrick, M. J., and R. A. Edwards. 1995. Nitrogen control in bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 59:604-622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neidhardt, F. C., P. L. Bloch, and D. F. Smith. 1974. Culture medium for enterobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 119:736-747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pettersen, E. F., T. D. Goddard, C. C. Huang, G. S. Couch, D. M. Greenblatt, E. C. Meng, and T. E. Ferrin. 2004. UCSF Chimera: a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25:1605-1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rhee, S. G., B. Chock, and E. R. Stadtman. 1989. Regulation of Escherichia coli glutamine synthetase. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 62:37-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schreier, H. J., S. W. Brown, K. D. Hirschi, J. F. Nomellini, and A. L. Sonenshein. 1989. Regulation of Bacillus subtilis glutamine synthetase gene expression by the product of the glnR gene. J. Mol. Biol. 210:51-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strauch, M. A., A. I. Aronson, S. W. Brown, H. J. Schreier, and A. L. Sonenshein. 1988. Sequence of the Bacillus subtilis glutamine synthetase gene region. Gene 71:257-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tullius, M. V., G. Harth, and M. A. Horwitz. 2003. Glutamine synthetase GlnA1 is essential for growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human THP-1 macrophages and guinea pigs. Infect. Immun. 71:3927-3936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weisbrod, R. E., and A. Meister. 1973. Studies on glutamine synthetase from Escherichia coli. Formation of pyrrolidone carboxylate and inhibition by methionine sulfoximine. J. Biol. Chem. 248:3997-4002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woolfolk, C. A., and E. R. Stadtman. 1964. Cumulative feedback inhibition in the multiple end product regulation of glutamine synthetase activity in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 17:313-319. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wray, L. V., Jr., M. R. Atkinson, and S. H. Fisher. 1994. The nitrogen-regulated Bacillus subtilis nrgAB operon encodes a membrane protein and a protein highly similar to the Escherichia coli glnB-encoded PII protein. J. Bacteriol. 176:108-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wray, L. V., Jr., A. E. Ferson, K. Rohrer, and S. H. Fisher. 1996. TnrA, a transcriptional factor required for global nitrogen regulation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:8841-8845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wray, L. V., Jr., and S. H. Fisher. 2005. A feedback-resistant mutant of Bacillus subtilis glutamine synthetase with pleiotropic defects in nitrogen-regulated gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 280:33298-33304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wray, L. V., Jr., J. M. Zalieckas, and S. H. Fisher. 2001. Bacillus subtilis glutamine synthetase controls gene expression through a protein-protein interaction with transcription factor TnrA. Cell 107:427-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshida, K., H. Yamaguchi, M. Kinehara, Y. Ohki, Y. Nakaura, and Y. Fujita. 2003. Identification of additional TnrA-regulated genes of Bacillus subtilis associated with a TnrA box. Mol. Microbiol. 49:157-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]