Abstract

DNA damage repair mechanisms have been most thoroughly explored in the eubacterial and eukaryotic branches of life. The methods by which members of the archaeal branch repair DNA are significantly less well understood but have been gaining increasing attention. In particular, the approaches employed by hyperthermophilic archaea have been a general source of interest, since these organisms thrive under conditions that likely lead to constant chromosomal damage. In this work we have characterized the responses of three Sulfolobus solfataricus strains to UV-C irradiation, which often results in double-strand break formation. We examined S. solfataricus strain P2 obtained from two different sources and S. solfataricus strain 98/2, a popular strain for site-directed mutation by homologous recombination. Cellular recovery, as determined by survival curves and the ability to return to growth after irradiation, was found to be strain specific and differed depending on the dose applied. Chromosomal damage was directly visualized using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and demonstrated repair rate variations among the strains following UV-C irradiation-induced double-strand breaks. Several genes involved in double-strand break repair were found to be significantly upregulated after UV-C irradiation. Transcript abundance levels and temporal expression patterns for double-strand break repair genes were also distinct for each strain, indicating that these Sulfolobus solfataricus strains have differential responses to UV-C-induced DNA double-strand break damage.

Cells have evolved molecular mechanisms to meet the challenge of maintaining genomic integrity by rapidly responding to environmental stresses that can damage proteins and DNA. One of the most common forms of damage is caused by UV light (UV) exposure. High-energy short-wavelength UV-C light is absorbed directly by DNA and induces both cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers between adjacent thymidine or cytosine residues as well as pyrimidine-pyrimidone photoproducts between adjacent pyrimidine residues. Mechanisms for repair of these lesions appear to be present in all organisms and are thought to occur through either light-independent nucleotide excision repair (NER) or light-dependent photoreactivation using photolyases (for reviews, see references 33 and 34). UV-C irradiation also causes the production of reactive oxygen species, which can result in DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) (6, 44). Our primary understanding for repair of DSBs has come from studies focused primarily on bacteria and eukaryotes. In Escherichia coli, these breaks are repaired through the action of the RecA protein, which assists in recombinational repair of single-strand regions produced through replication fork arrest at UV lesions and in DSB repair by extended synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA) and homologous recombination (9, 19). Eukaryotes employ nonhomologous end joining as well as DSB repair by SDSA and homologous recombination mechanisms to repair these breaks (for recent reviews, see references 20 and 21).

The archaeal domain is distinct from the bacterial and eukaryotic branches of life and includes organisms that inhabit extreme environmental habitats that might be expected to accelerate spontaneous DNA damage. Interest in these microbes has grown steadily since their identification, as species living under such conditions are likely to have robust mechanisms to contend with continual genomic insults. In particular, DNA damage repair and genomic stability have been the focus of several recent studies in the archaea. Two genome-wide efforts with Halobacterium strain NRC-1 have focused on transcription following UV irradiation and demonstrated that at high doses, photoreactivation is a major mechanism for repair, while at lower doses, homologous recombination is involved in correction of DNA damage (4, 24). Sulfolobus spp. occupy terrestrial hot springs with temperatures ranging from 70 to 85°°C, an environment that is likely to lead to DNA damage by generation of reactive oxygen species, hydrolytic deamination of nucleotide bases, and UV exposure. Studies of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius have shown that cellular sensitivity to UV irradiation and spontaneous mutation rates are similar to those of E. coli, indicating efficient DNA damage repair in these hyperthermophiles (15, 46). Additionally, photoreactivation-based repair and genetic marker exchange were apparent during exposure to visible light, suggesting that DNA lesions and DSBs stimulate exchange (11, 36). Genome-wide transcriptional examination of the UV damage response in Sulfolobus solfataricus strains PH1 and P2 and in S. acidocaldarius showed an apparent increase of no more than 2-fold in expression of DNA repair genes, suggesting a potential lack of repair pathway inducibility (11, 12).

S. solfataricus has emerged as a popular model system for hyperthermophilic archaea, since it is relatively easy to grow in the laboratory in liquid medium as well as on plates. S. solfataricus strain 98/2 has become especially useful, since a genetic selection system utilizing lactose and the lacS gene has been developed and directed gene replacement through homologous recombination has been demonstrated (35, 47). Curiously, while equivalent lacS mutant backgrounds exist in other strains (specifically S. solfataricus strains PH1 and P2), efforts at in vivo-directed gene replacement have thus far been successful only in strain 98/2 (8, 10, 16, 18, 23, 45). The apparent inability of some S. solfataricus strains to perform homologous recombination-based gene replacement suggests a fundamental difference in the repair mechanisms employed from strain to strain and prompted our comparison of cellular DNA damage repair. We specifically examined three S. solfataricus strains, strain P2 obtained from two different sources and strain 98/2. Here we describe the differential ability of the strains to survive UV-C irradiation and the rates at which they return to growth. Additionally, we describe the rate of chromosome repair following UV-C-induced DSB formation and the transcriptional response of DNA damage repair genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultivation and UV exposure.

For all three S. solfataricus strains, the cells were grown to an optical density at 540 nm of 0.2 to 0.4 in basal salts medium as described previously (30) containing 0.1% (wt/vol) sucrose and 0.1% (wt/vol) tryptone (ST medium) or 0.2% (wt/vol) glucose and 0.2% (wt/vol) tryptone (GT medium) prior to UV exposure. The cells were exposed to 0, 100, 200, or 300 mJ/cm2 of UV-C (UVC-508; Ultra-Lum Inc., Claremont, CA). Irradiated cells were then added to prewarmed ST medium and cultivated in the dark at 80°°C with shaking. For viable-cell determination, irradiated and control samples were grown in GT medium, diluted using the same medium, and plated in the dark on 0.8% (wt/vol) Gelrite (Kelco) GT plates at a pH of 3.0. The plates were incubated at 80°°C in a humid chamber for approximately 5 days, and colonies were counted. Growth rates were determined by spectrophotometric analysis at 540 nm of cultures grown in liquid, and generation times were calculated using Prizm 4.0 software using a minimum of seven independent cultures. Representative returns to growth curves were determined by analysis of three separate growth cycles.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

The cells were grown to early log phase (optical density at 540 nm of 0.2 to 0.4) and exposed to a UV dose of 100 mJ/cm2 and then returned to growth. At the indicated times, 4 ×× 109 cells were removed and collected by centrifugation at 4°°C. The cells were resuspended in 0.5 volume of 1×× medium salts, warmed to 50°°C, and added to 0.5 volume of melted 2% agarose (InCert). Plugs were cast using a mold (Bio-Rad) and solidified at 4°°C. Solidified plugs were treated in 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA plus 1% N-lauroyl sarcosine sodium salt and 1 mg/ml proteinase K (Bioline) overnight at 50°°C. This was followed by a second overnight incubation in proteinase K at 50°°C. The plugs were then washed 3 times for 30 min each time in ET buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 50 mM EDTA) and then washed 3 times for 30 min each in 0.1×× ET buffer. After the agarose plugs were washed with TE buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA) two times for 10 min each time, they were then subjected to digestion by SfiI (NEB) for 4 h using the manufacturer's recommended conditions in a total volume of 250 μμl. DNA was analyzed using a Bio-Rad CHEF-DR III system with a buffer temperature of 14°°C. The gels were made of 1% agarose, 0.5×× TBE (9 mM Tris, 9 mM boric acid, 0.2 mM EDTA) and were run for 24 h at 5.5 V/cm using a 120o included angle with switch times of 60 to 120 s. The gels were subsequently stained with ethidium bromide and photographed with a Geneflash gel documentation system (Syngene). Chromosome repair was measured using the GeneTools (Syngene) quantification software. The zero-hour time point (untreated sample) was designated 100% repair. The values for 24-h time points were normalized to the values for untreated samples.

PCRs.

Standard PCRs were performed in 1×× ThermoPol buffer (New England BioLabs [NEB]) with 200 pmol of the appropriate primer (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), 200 μμM dinucleotide triphosphates (NEB), and 2.5 U Taq (NEB). PCRs for gene sequencing were performed in 1×× ExTaq buffer (Takara Bio) with 200 pmol of the appropriate primer, 200 μμM dinucleotide triphosphates (NEB), and 1.25 U ExTaq (Takara Bio).

Gene sequencing and sequence analysis.

Gene sequencing was performed by Amplicon Express (Pullman, WA). DNA sequences were converted to protein sequence using the Translate++ program (SeqWeb GCG Wisconsin Sequence Analysis Package). Protein alignments were produced using the Pretty program (SeqWeb GCG Wisconsin Sequence Analysis Package), and differing residues were highlighted by hand. Gene sequences were found to match genome information available at the NCBI with the exception of the S. solfataricus strain P2-A ral2 sequence, which has been deposited in GenBank under accession number HM462249. BLAST analysis for the novel insertion in the strain 98/2 rad54 gene was performed using the 327-bp insertion sequence as a query with nucleotide BLAST and the Sulfolobus genome information available at the NCBI website.

RNA isolation and cDNA preparation.

Samples in 6- to 10-ml volumes were removed from cultures grown as described above at the times indicated. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 10,500 ×× g. RNA was isolated using the RiboPure bacteria kit (Ambion) and the manufacturer's protocol. Contaminating DNA was removed from RNA samples using the DNA-free kit (Ambion) following the manufacturer's protocol. Resulting nucleic acid samples were quantified at 260 nm using a Coulter Beckman DU-800 spectrophotometer. cDNA was prepared from DNA-free RNA using the RevertAid first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentas) with the random hexamer primer and by using the manufacturer's recommendations.

qRT-PCR.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed with 10 ng template cDNA, Fast SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems), and 180 pmol of each primer (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) in a 20-μμl reaction volume. qRT-PCR was performed using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system using the Fast, ΔΔΔΔCT, SYBR green settings. cDNA template was validated over 4 orders of magnitude, following the manufacturer's protocol. Transcript levels were normalized to the S. solfataricus 23S rRNA gene (annotated as Ssor04 at http://www-archbac.u-psud.fr/projects/sulfolobus/). Normalized gene expression was calculated using the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method, also known as the ΔΔΔΔCT method (22, 37). ΔΔΔΔCT calculations were performed using the equations provided in the user bulletin for the ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (2a).

RESULTS

Cellular response following UV-C radiation exposure was variable and dependent on the source of the strain.

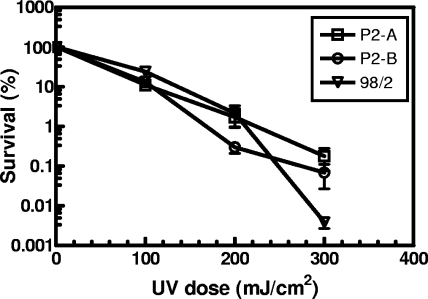

We examined three separate sources of S. solfataricus strains for cellular resistance to UV-C irradiation (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Strain P2-A was purchased directly from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and is designated S. solfataricus P2 as deposited by Wolfram Zillig into the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH (DSMZ). Strain P2-B was acquired from Yvan Zivanovic (Université Paris-Sud) and was used in the S. solfataricus P2 genome sequencing project (40). Strain 98/2 was provided by Paul Blum (University of Nebraska--Lincoln) and has been the subject of recent genomic sequencing efforts (GenBank accession no. ACUK00000000 and CP001800.1). We found that the strains showed differing responses to UV damage that were dependent on the dose applied. Cellular survival was determined by colony formation on solid medium and is shown in Fig. 1. At the lowest UV dose of 100 mJ/cm2, all three strains demonstrated resistance, with a survival rate as high as 23% for strain 98/2 and survival rates of 11% and 13% for strains P2-A and P2-B, respectively. At a UV dose of 200 mJ/cm2, the P2-A and 98/2 strains showed nearly identical sensitivities, with cellular survival between 1.7 and 2.2%. The P2-B strain was more sensitive to UV damage at this higher dose, displaying 5- to 7-fold-lower survival than the other two strains. At the highest UV dose of 300 mJ/cm2, strain 98/2 was the most sensitive strain, exhibiting only 0.004% survival compared to 0.18% and 0.08% survival for strains P2-A and P2-B, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Representative survival curves for three S. solfataricus strains following exposure to UV-C radiation. Survival of strains P2-A, P2-B, and 98/2 is shown. Values are the means ±± standard deviations (error bars) for triplicate experiments (plated in duplicate). Many of the error bars for survival data were smaller than the symbol and are therefore not visible in the figure.

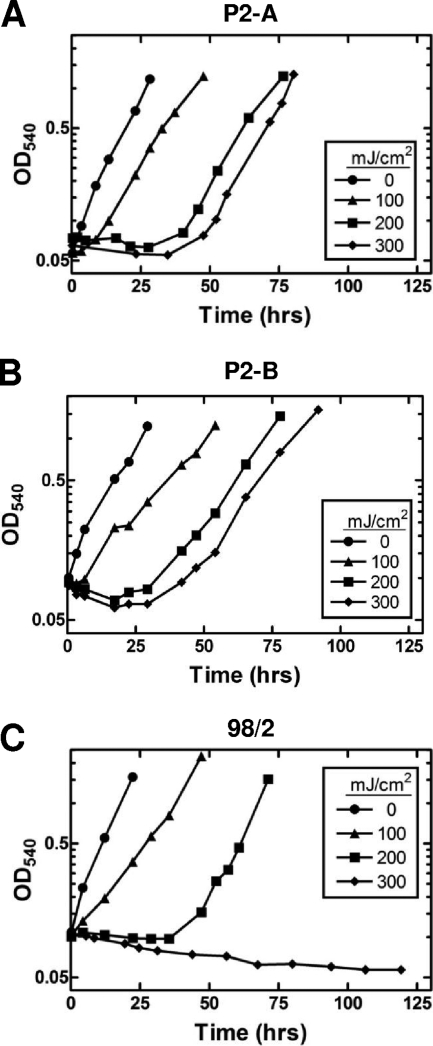

To better assess the ability of S. solfataricus to recover from UV-C damage, we examined the return of the cells to growth in liquid medium. Each strain was exposed to various doses of UV light, and growth was monitored by measuring the optical density (Fig. 2). In the absence of UV damage, the strains showed slightly different generation times in rich medium. Strain 98/2 grew the most rapidly, with a doubling time of approximately 5.9 h ±± 0.7 h. The next fastest growth rate was seen with strain P2-A, with a doubling time of approximately 7.5 ±± 0.6 h. Strain P2-B grew more slowly than either strain 98/2 or P2-A and had a doubling time of approximately 8.3 ±± 1.3 h. After exposure to 100 mJ/cm2 UV-C irradiation, all three strains began recovery in the first 4 to 5 h, although at a slightly diminished growth rate. Strain 98/2 recovered the most quickly from a low UV-C dose, within 2 h following exposure to 100 mJ/cm2, which was not unexpected based on observed higher survival rates on solid medium as shown in Fig. 1. Both P2 strains restarted growth approximately 4 to 6 h earlier than strain 98/2 following exposure to 200 mJ/cm2. After application of the highest UV-C dose of 300 mJ/cm2, both P2 strains (P2-A and P2-B) demonstrated recovery as measured by growth by 30 h after exposure. Strain 98/2, however, did not recover from this exposure within the first 100 h. Although the two higher doses of UV-C irradiation (200 and 300 mJ/cm2) required significantly longer time periods for restarted growth to be detected than the 100-mJ/cm2 dose, the growth rates achieved upon regrowth were similar to those observed in the absence of UV-C exposure. Taken together with the survival curve data, these results suggest that there may be a differential response to UV damage in the three strains.

FIG. 2.

Representative growth curves showing the effect of irradiation on return to growth. Cells were treated with various doses of UV-C irradiation and then returned to growth in the dark. Culture growth was measured by optical density at 540 nm (OD540). Strains P2-A (A), P2-B (B), and 98/2 (C) were examined. The UV doses were 0, 100, 200, and 300 mJ/cm2.

Chromosomal repair rates differed between the strains under identical conditions.

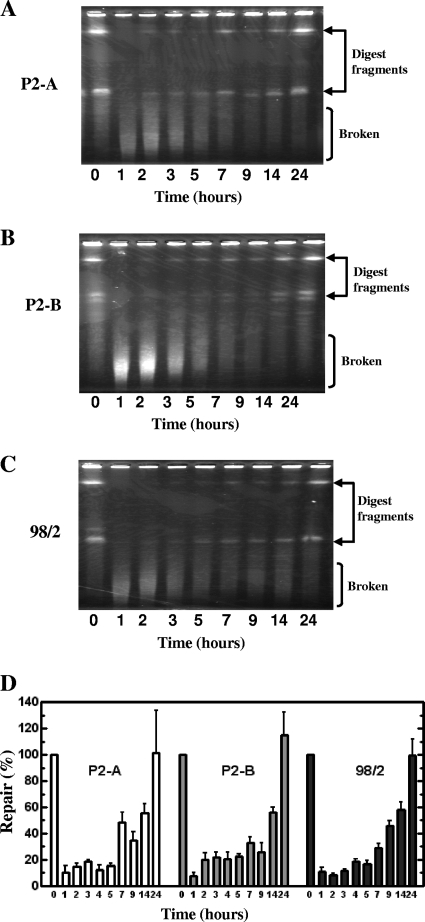

It has been previously reported that UV treatment of S. solfataricus strain PH1 results in double-strand break formation, with breaks likely arising from the presence of lesions that remain unrepaired as the cells progress through replication (11). To evaluate the ability of each strain to repair damage, we used pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) to directly visualize the state of the chromosome for both P-2 strains and strain 98/2 (Fig. 3). To date, all published Sulfolobus genomes have been reported to be circular and consist of close to 3,000 genes (7, 17, 40). S. solfataricus strain P2-B was the subject of the first Sulfolobus genome sequencing project and has a circular genome of 2.99 Mbp with 3,287 open reading frames and a GC content of 35.8% (40). The other S. solfataricus P2 strain, P2-A, is annotated as the same strain as P2-B at the ATCC and is expected to have a genome of similar composition. While not yet published, publicly available sequence information for strain 98/2 has recently been found to have a 2.68-Mbp genome of 35.4% GC with 3,055 predicted open reading frames (GenBank accession no. ACUK00000000 and CP001800.1).

FIG. 3.

Repair of S. solfataricus chromosomal DNA following UV-C irradiation at 100 mJ/cm2 as visualized by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Representative gels are shown for each of the three strains (strain P2-A [A], P2-B [B], and 98/2 [C]) where each lane contains DNA extracted from 5 ×× 108 cells as visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. Chromosomal DNA was digested with SfiI, and the restriction fragments are indicated by the arrows, while fragments resulting from DSB formation are labeled broken. The length of time after irradiation is shown in hours. The rate of repair for each strain was determined by quantitation of the largest digest fragment and is shown as the average of four to seven replicate experiments in panel D.

To better visualize chromosome repair by PFGE, genomic DNA was subjected to restriction endonuclease digestion using SfiI. This enzyme was anticipated to cut rarely in the S. solfataricus genome due to a 13-bp recognition sequence that requires a 4-bp GC sequence at each end. We chose the 100-mJ/cm2 irradiation dose to assess chromosome damage and repair, since cellular survival was found to be at least 10% for each of the strains under these conditions (as shown in Fig. 1). In the absence of UV-C irradiation, indicated as the time zero lane for each gel, from the digested chromosome, two distinct bands for strain P2-A were observed (Fig. 3A). Four distinct digest fragments were apparent for strain P2-B, while three fragments were seen for strain 98/2 (Fig. 3B and C, respectively). The different digest patterns suggest that there is some sequence disparity between the two P2 strains that results in the presence of additional or differentially located restriction sites. Within 1 h of UV-C irradiation, double-strand break formation was apparent for each of the strains and manifested as lower-molecular-weight smears seen toward the bottom of the gels that is concurrent with the loss of the digest fragments observed before irradiation. The state of the chromosome was assessed over a period of 24 h following the return to growth, and during this time, the low-molecular-weight DNA smears resolved into the digest fragments that are indicative of an intact chromosome. Among the three strains, strain P2-B appeared to have the most accumulated breaks as indicated by the intensity of the lower-molecular-weight smears (Fig. 3B). This strain demonstrated an approximate 50% chromosomal repair rate by 14 h after returning to growth, while the other two strains achieved approximately 50% repair several hours sooner; for strain P2-A, this occurred between 7 and 9 h, and for strain 98/2, this level of repair was apparent at 9 h (Fig. 3D). Overall, strain 98/2 demonstrated the slowest average recovery from UV-C-induced double-strand breaks as shown by quantification of restriction fragments at the 2-, 3-, 5-, and 7-h time points compared to the P2 strains (Fig. 3D).

Genes implicated in DSB repair were transcriptionally upregulated in response to UV-C irradiation.

Several genes have been identified in Sulfolobus species that are expected to be involved in DSB repair in vivo. Biochemical studies have elucidated the activities of the RadA protein (a homologue of eukaryotic Rad51 and bacterial RecA proteins) from both S. solfataricus and Sulfolobus tokodaii and the Rad54 protein from S. solfataricus and suggest that these proteins are involved in the repair of DNA DSBs through homologous recombination (3, 14, 31, 38, 39, 42, 48). The Mre11 protein from Sulfolobus acidocaldarius has been found to be associated with DNA following damage and directly interacts with Rad50, implying a role in break repair for both of these proteins (28). RadA paralogues identified in S. solfataricus and S. tokodaii were initially implicated in DSB repair by virtue of their homology to the RadA protein, but subsequent efforts indicate that at least some of these proteins are directly involved in the repair process (1, 25, 41, 42). These paralogue proteins have previously been described as members of the newly designated archaeal RadC (aRadC) family (13), but no gene names have been assigned to the individual open reading frames (ORFs) apart from the corresponding P2 genome project number in the case of the three paralogues found in S. solfataricus (1, 25). Since our study includes examination of the paralogue genes in more than one S. solfataricus strain and use of a single ORF designation relating to just one genome project could be confusing, for simplicity here we have named the genes encoding the paralogues ral genes (for radA-like), where the published P2 ORF Sso2452 is ral1, ORF Sso0777 is ral2, and ORF Sso1861 is ral3. The corresponding genes in strains P2-A and 98/2 are named in the same manner.

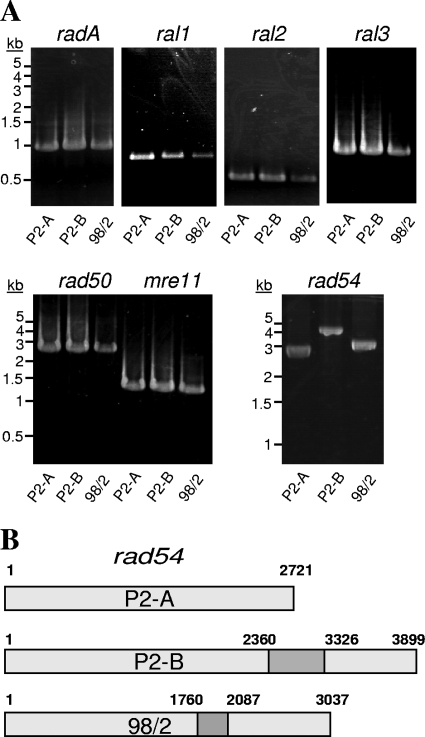

To examine the possibility that the expression of these genes could be involved in the DSB repair observed by PFGE, we first verified the presence of each gene in the three S. solfataricus strains. PCR primers were designed based on P2 nucleotide sequences from GenBank (accession no. AE006641) and used to amplify the putative DSB repair-associated genes from all three strains (Fig. 4). We found that each strain carries the radA gene, all three ral genes (ral1, ral2, and ral3) and rad50, mre11, and rad54. Every gene was of the expected size based on the published S. solfataricus P2 genome, with the exception of the rad54 gene (Fig. 4A). rad54 PCR amplification products were of different sizes in each of the three strains, with the largest PCR amplicon found in strain P2-B and the smallest in strain P2-A. Sequencing of the rad54 amplicons showed the presence of insertions that resulted in larger DNA products following PCR amplification (Fig. 4B). The rad54 gene from strain P2-A appears to be the intact wild-type sequence and is 2,721 bp in length. The insertion in the rad54 gene from strain P2-B is identical to that reported in the published S. solfataricus P2 genome sequence (14, 40) and is the 966-bp insertion element ISC1173. The insertion in the rad54 gene of strain 98/2 is smaller than that in strain P2-B and in a different location. This insertion is 327 bp in length and when used as a query in BLAST analysis, is more than 90% identical to 7 sequences of identical size found across the genome of strain 98/2. Each of these 7 additional sequences is located in a probable intergenic region, suggesting that the insertion is likely noncoding and could be derived from a insertion element. The insertions in the rad54 genes of strains P2-B and 98/2 result in premature stop codons that are likely to preclude production of full-length protein in vivo.

FIG. 4.

PCR amplification of genes likely to be involved in double-strand break repair. (A) The genes encoding RadA, Ral1, Ral2, Ral3, Rad50, Mre11, and Rad54 were amplified from genomic DNA isolated from strains P2-A, P2-B, and 98/2 as indicated. The products were electrophoresed using gels of 0.8% agarose and 1×× TBE and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. (B) Schematic representation of the insertions present in the rad54 gene in strains P2-B and 98/2. Uninterrupted rad54 from strain P2-A is shown at the top. The insertion in rad54 from strain P2-B begins at nucleotide 2360 and is 966 bp in length, while the rad54 insertion in strain 98/2 begins at nucleotide 1760 and is 327 bp in length.

Additional sequence analysis revealed that radA, ral3, rad50, and mre11 are identical in all three strains examined, but there are nucleotide differences in the ral1 and ral2 genes. For comparative purposes, we determined gene sequence identity using the P2-B sequence as a reference, as it currently serves as the sequenced type strain for S. solfataricus. Nucleotide sequences for ral1 were 100% identical in strains P2-A and 98/2, but the P2-B sequence differed at 97 specific residues and was only 87.7% identical; at the protein sequence level, the Ral1 proteins of strains P2-A and 98/2 were 100% identical to each other but only 95% identical to the Ral1 protein of strain P2-B (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). ral2 gene sequences for strains P2-A and 98/2 were 99.4% identical to each other, differing at just 3 nucleotides. Following gene translation, the resulting protein sequences were 99% identical to each other. In comparison with ral2 sequence from strain P2-B, ral2 in strain P2-A was 89.2% identical and in strain 98/2 was 88.6% identical. Translation of the ral2 gene from strain P2-A resulted in a sequence that is 93% identical to that of strain P2-B, while the Ral2 protein sequence from strain 98/2 was only 91% identical to that from strain P2-B (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

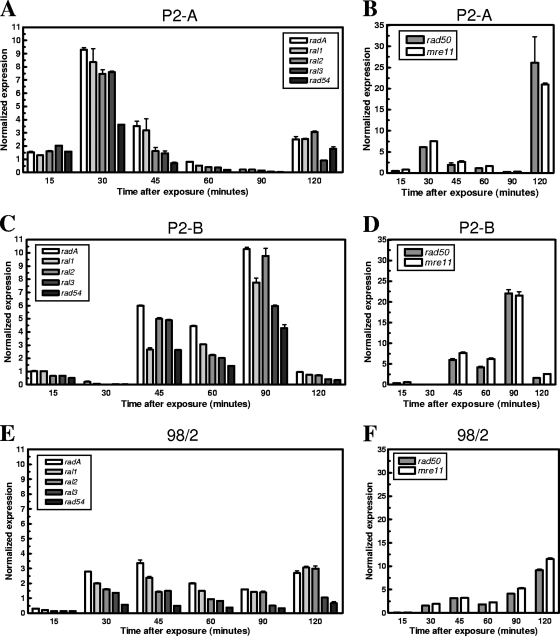

Using quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase PCR and the Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR detection system, we determined the levels of expression for radA, ral1, ral2, ral3, rad50, mre11, and rad54 in all three S. solfataricus strains following exposure to 100 mJ/cm2 of UV-C irradiation (Fig. 5). We found that expression for this subset of genes after DNA damage was different for each strain both over time and in intensity. Strain P2-A showed the earliest transcriptional response, with the highest level of expression of radA, ral1, ral2, ral3, and rad54 occurring 30 min after exposure (Fig. 5). We observed an increase of more than 9-fold in the expression of radA in strain P2-A at the 30-min time point, with expression decreasing over subsequent time points, followed by a mild increase in expression of more than 2-fold 120 min after UV-C exposure (Fig. 5A). Similar increases in transcription and equivalent timing were observed for each of the ral transcripts as well as the rad54 transcript, with the highest level of expression occurring at 30 min, which then tapered off over the remainder of the time course. Strain P2-B showed comparable expression level increases for each of the genes, but the timing of increased expression was different from that of strain P2-A (Fig. 5C). Levels of transcript production were found to begin to increase 45 min after exposure, with peak expression for the radA, ral, and rad54 transcripts occurring 90 min after damage. The radA paralogues and rad54 were also induced for expression, with upregulation ranging between 6- and 10-fold for the ral genes and more than 4-fold induction for rad54. Expression levels for rad50 and mre11 transcripts were much higher than those observed for the radA, ral, and rad54 genes for strains P2-A and P2-B (Fig. 5B and D). More than 20-fold induction for rad50 and mre11 was seen in both cases but at differing times. Significant induction of transcription from these genes occurred 120 and 90 min after damage for strains P2-A and P2-B, respectively, with lower levels of transcript production during the remainder of the time course.

FIG. 5.

Quantitative real-time PCR detection of transcripts from likely DSB repair genes following UV-C irradiation. Cells from each of the three strains were exposed to 100 mJ/cm2 of UV-C irradiation, and RNA samples were isolated at the times indicated. Normalized expression levels for radA, ral1, ral2, ral3, and rad54 transcripts from strains P2-A, P2-B, and 98/2 are shown in panels A, C, and E, respectively. Normalized transcript expression levels for rad50 and mre11 are represented for strains P2-A, P2-B, and 98/2 in panels B, D, and F, respectively. Experimental results are shown as the averages plus standard deviations (error bars) from a minimum of three replicates.

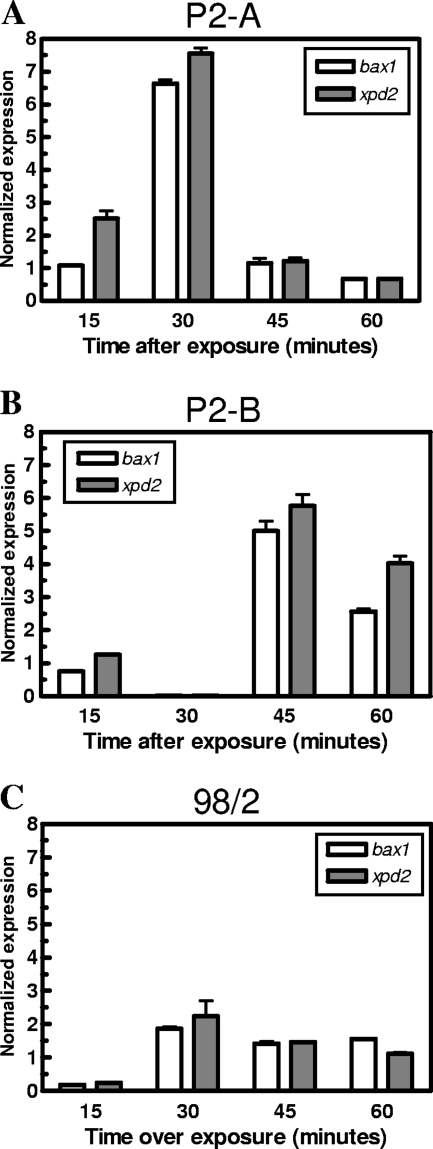

Strain 98/2 showed the weakest transcriptional response for all the genes examined relative to the 23S rRNA gene, with levels of radA transcript never exceeding a 3-fold increase at any point over the time course (Fig. 5E). The ral and rad54 genes from strain 98/2 were similarly not highly induced for transcription over the period examined following damage. For rad50 and mre11, strain 98/2 again showed a reduced transcriptional response to damage, with induction of these genes at a much lower level than that seen for the P2 strains, increasing to a maximum of only 10-fold (Fig. 5F). The overall reduced transcriptional response of strain 98/2 suggested that strain 98/2 reacts to UV-C DNA damage by upregulating DSB repair genes at a low level over an extended period of time or that this strain utilizes an alternate pathway for repair. An alternate pathway could involve nucleotide excision repair, and recently, nucleotide excision-related proteins have been identified and characterized for S. solfataricus. Specifically, the Sulfolobus XPB-Bax1 protein complex is likely equivalent to eukaryotic XPG and has been shown to function as a helicase-nuclease responsible for unwinding and cleaving DNA substrates that mimic those likely to be abundant during nucleotide excision repair processes (29, 32, 43). We therefore examined gene expression levels for bax1 and xpd2 over a similar time course for each of the three strains (Fig. 6). Strain P2-A showed the earliest transcriptional induction for these genes, with expression levels reaching more than 6.5-fold 30 min after damage, while strain P2-B transcription levels reached a maximum of more than 5-fold after 45 min (Fig. 6A and B). Strain 98/2 did not demonstrate significant induction of either bax1 or xpd2 following UV-C irradiation but instead displayed a low-level (no more than 2-fold) persistent increase in transcript production over the time course (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

Quantitative real-time PCR detection of transcripts from bax1 and xpd2 following UV-C irradiation. Cells from each of the three strains were exposed to 100 mJ/cm2 of UV-C irradiation, and RNA samples were isolated at the times indicated. Normalized expression levels for bax1 and xpd2 transcripts from strains P2-A, P2-B, and 98/2 are shown in panels A, B, and C, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This work demonstrates that three S. solfataricus strains have marked physiological differences in their response to DNA damage induced by exposure to UV-C irradiation. Our survival curves indicated that strain 98/2 was the most vulnerable to high UV-C doses, but it had slightly more resistance to lower doses than strain P2-A or P2-B did. To our surprise, two P2 strains from two different sources (one was purchased from ATCC, and another was obtained directly from the sequencing project) were strikingly different. Survival varied following UV-C exposure and was dependent on dose, with strain P2-B displaying more overall sensitivity to damage than strain P2-A. The differences between these two strains were again apparent in the rate at which chromosomal DSB repair occurs. While strain P2-B shows early immediate repair, this is followed by a prolonged delay, and 50% genomic repair is not achieved until several hours after the same point is reached in strain P2-A. Sequence variations were also found between the two P2 strains; several of the genes we examined were identical, but nucleotide disparities were directly apparent in the ral1 and ral2 genes and the P2-B rad54 gene is interrupted by an insertion sequence. Variability in sequence was also indirectly indicated through the differential SfiI genome digestion patterns. Although we cannot, in the work described here, ascertain the extent of sequence variation between the two strains identified as P2, the data do suggest that the strains are not interchangeable. Additional sequencing efforts will be necessary to further delineate the differences between the two strains.

Examination of the cellular transcriptional response to DSBs caused by UV-C damage indicates that the timing and intensity of gene expression are dependent on the strain. Strain 98/2 responds to damage with a somewhat consistent low-level gene expression pattern that begins within the first 30 min. In contrast, strains P2-A and P2-B have a more robust response and strongly upregulate radA, ral1, ral2, ral3, rad54, rad50, and mre11. We were again able to discern differences in the elevated transcriptional responses of the two P2 strains. Strain P2-A responds to damage more quickly than strain P2-B does and also modulates gene expression more tightly, exhibiting a burst of expression between 30 and 45 min after damage. In contrast, strain P2-B initiates transcriptional upregulation later, 45 min after damage, but persists in increased transcript production that peaks 90 min after damage. Overall, we found that despite the nuances in timing and duration, expression of DSB repair genes was clearly temporal in nature, and the response time was rapid for the P2 strains. Over the time course examined, strain 98/2 never induced expression of the DSB repair genes to the level seen for the P2 strains and appeared to respond to UV-C DNA break damage by modestly upregulating these genes but maintaining this level of expression for a prolonged time.

Our transcriptional studies have demonstrated for the first time that there is a measurable regulatory response to DSB damage arising from UV-C irradiation in S. solfataricus that involves multiple genes. Prior to this work, the only report of increased expression of DSB-related genes following UV irradiation showed moderate transcriptional elevation (between 2- and 3-fold) for rad50 and mre11 in S. solfataricus strain PH1 (11). Each of the strains we examined in this work increase expression of genes expected to be involved in DSB repair to various levels in response to damage incurred by UV-C. The induction of rad54 and the ral genes observed here is the first indication of an in vivo role for Rad54 and Ral proteins in DNA damage repair in Sulfolobus. Additionally, we found that the rad54 gene is not essential for S. solfataricus, as the presence of insertions in the coding sequence were well tolerated by the cell. There is no apparent correlation between the state of the rad54 gene and the ability of cells to recover from UV-C-induced DNA damage; further understanding of the role Rad54 protein plays in vivo for DSB repair will best be achieved through isogenic mutant strain construction.

Overall, the cellular response to UV-C damage was clearly strain dependent, and the window of gene expression was transient. This was especially apparent for strain P2-A. The largest transcriptional increase occurs 30 min after exposure in strain P2-A, but transcript levels were significantly lower 15 min earlier or later in the time course. Transcript stability in S. solfataricus has been shown to be variable, with some RNAs having very short half-lives and some remaining stable for as long as 2 h (2, 5). It is possible that expression of DSB repair genes is even more highly upregulated than we were able to detect, as our time points were a full 15 min apart and RNA turnover could be rapid. Prior to this work, no significant increase in DSB repair-related gene expression in response to UV damage has been reported for S. solfataricus. Genome-wide microarray experiments for strains PH1 and strain P2 (obtained from the DSMZ) indicated only mild increases (up to 2-fold) in transcription for DSB repair genes (11, 12). This disparity could be the result of differential sensitivity between microarray data and quantitative real-time PCR or could arise from simple strain differences. Strain PH1 and the DSMZ-derived P2 strain might be more like strain 98/2 in their response to UV damage and induce expression of DSB repair genes at a low level that persists over a period of time.

We have identified a fundamental difference in the physiological response to UV-C damage in the P2 strains and in strain 98/2 that is most pronounced at the transcript induction level. The experimentally useful ability of strain 98/2 to permit site-directed gene replacement through homologous recombination could be the result of the observed mild but persistent upregulation of DSB repair protein transcripts following the application of a DNA damaging agent, in this case UV-C irradiation. DNA uptake by S. solfataricus is facilitated by electroporation, a transformation method that has been reported to cause cellular damage by inducing DNA breaks (26, 27). Assuming similar DSB repair protein stability in vivo in Sulfolobus, it may be that the ease with which strain 98/2 performs directed gene replacement using exogenous DNA is the result of persistent DSB repair pathway induction that would give cells an extended opportunity to accomplish homologous recombination. A shorter length of time of expression of DSB repair genes in the P2 strains may result in a more abbreviated time frame for efficient homologous recombination and could explain the failure of site-directed gene replacement efforts in these strains.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society IRG-77003-26 and from the National Science Foundation MCB-0951125.

We thank Yvan Zivanovic and Paul Blum for their generous gifts of S. solfataricus strains P2 and 98/2, respectively. Both Andy Galbraith and Bill Graham critically read the manuscript. Additionally, we thank Andy Galbraith for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 July 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abella, M., S. Rodriguez, S. Paytubi, S. Campoy, M. F. White, and J. Barbe. 2007. The Sulfolobus solfataricus radA paralogue sso0777 is DNA damage inducible and positively regulated by the Sta1 protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:6788--6797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson, A. F., M. Lundgren, S. Eriksson, M. Rosenlund, R. Bernander, and P. Nilsson. 2006. Global analysis of mRNA stability in the archaeon Sulfolobus. Genome Biol. 7:R99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Applied Biosystems. 2001. User bulletin #2 for the ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system. Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA.

- 3.Ariza, A., D. J. Richard, M. F. White, and C. S. Bond. 2005. Conformational flexibility revealed by the crystal structure of a crenarchaeal RadA. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:1465--1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baliga, N. S., S. J. Bjork, R. Bonneau, M. Pan, C. Iloanusi, M. C. Kottemann, L. Hood, and J. DiRuggiero. 2004. Systems level insights into the stress response to UV radiation in the halophilic archaeon Halobacterium NRC-1. Genome Res. 14:1025--1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bini, E., V. Dikshit, K. Dirksen, M. Drozda, and P. Blum. 2002. Stability of mRNA in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. RNA 8:1129--1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cadet, J., E. Sage, and T. Douki. 2005. Ultraviolet radiation-mediated damage to cellular DNA. Mutat. Res. 571:3--17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, L., K. Brugger, M. Skovgaard, P. Redder, Q. She, E. Torarinsson, B. Greve, M. Awayez, A. Zibat, H. P. Klenk, and R. A. Garrett. 2005. The genome of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius, a model organism of the Crenarchaeota. J. Bacteriol. 187:4992--4999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper, C. R., A. J. Daugherty, S. Tachdjian, P. H. Blum, and R. M. Kelly. 2009. Role of vapBC toxin-antitoxin loci in the thermal stress response of Sulfolobus solfataricus. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37:123--126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Courcelle, J., J. R. Donaldson, K. H. Chow, and C. T. Courcelle. 2003. DNA damage-induced replication fork regression and processing in Escherichia coli. Science 299:1064--1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friest, J. A., Y. Maezato, S. Broussy, P. Blum, and D. B. Berkowitz. 2010. Use of a robust dehydrogenase from an archael hyperthermophile in asymmetric catalysis-dynamic reductive kinetic resolution entry into (S)-profens. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132:5930--5931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frols, S., P. M. Gordon, M. A. Panlilio, I. G. Duggin, S. D. Bell, C. W. Sensen, and C. Schleper. 2007. Response of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus to UV damage. J. Bacteriol. 189:8708--8718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gotz, D., S. Paytubi, S. Munro, M. Lundgren, R. Bernander, and M. F. White. 2007. Responses of hyperthermophilic crenarchaea to UV irradiation. Genome Biol. 8:R220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haldenby, S., M. F. White, and T. Allers. 2009. RecA family proteins in archaea: RadA and its cousins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37:102--107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haseltine, C. A., and S. C. Kowalczykowski. 2009. An archaeal Rad54 protein remodels DNA and stimulates DNA strand exchange by RadA. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:2757--2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobs, K. L., and D. W. Grogan. 1997. Rates of spontaneous mutation in an archaeon from geothermal environments. J. Bacteriol. 179:3298--3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonuscheit, M., E. Martusewitsch, K. M. Stedman, and C. Schleper. 2003. A reporter gene system for the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus based on a selectable and integrative shuttle vector. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1241--1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawarabayasi, Y., Y. Hino, H. Horikawa, K. Jin-no, M. Takahashi, M. Sekine, S. Baba, A. Ankai, H. Kosugi, A. Hosoyama, S. Fukui, Y. Nagai, K. Nishijima, R. Otsuka, H. Nakazawa, M. Takamiya, Y. Kato, T. Yoshizawa, T. Tanaka, Y. Kudoh, J. Yamazaki, N. Kushida, A. Oguchi, K. Aoki, S. Masuda, M. Yanagii, M. Nishimura, A. Yamagishi, T. Oshima, and H. Kikuchi. 2001. Complete genome sequence of an aerobic thermoacidophilic crenarchaeon, Sulfolobus tokodaii strain 7. DNA Res. 8:123--140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korencic, D., I. Ahel, J. Schelert, M. Sacher, B. Ruan, C. Stathopoulos, P. Blum, M. Ibba, and D. Soll. 2004. A freestanding proofreading domain is required for protein synthesis quality control in Archaea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:10260--10265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuzminov, A. 2001. DNA replication meets genetic exchange: chromosomal damage and its repair by homologous recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:8461--8468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lieber, M. R. 2010. The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79:181--211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lisby, M., and R. Rothstein. 2009. Choreography of recombination proteins during the DNA damage response. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 8:1068--1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25:402--408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandal, D., C. Kohrer, D. Su, S. P. Russell, K. Krivos, C. M. Castleberry, P. Blum, P. A. Limbach, D. Soll, and U. L. RajBhandary. 2010. Agmatidine, a modified cytidine in the anticodon of archaeal tRNA(Ile), base pairs with adenosine but not with guanosine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:2872--2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCready, S., J. A. Muller, I. Boubriak, B. R. Berquist, W. L. Ng, and S. DasSarma. 2005. UV irradiation induces homologous recombination genes in the model archaeon, Halobacterium sp. NRC-1. Saline Systems 1:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McRobbie, A. M., L. G. Carter, M. Kerou, H. Liu, S. A. McMahon, K. A. Johnson, M. Oke, J. H. Naismith, and M. F. White. 2009. Structural and functional characterisation of a conserved archaeal RadA paralog with antirecombinase activity. J. Mol. Biol. 389:661--673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meaking, W. S., J. Edgerton, C. W. Wharton, and R. A. Meldrum. 1995. Electroporation-induced damage in mammalian cell DNA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1264:357--362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meldrum, R. A., M. Bowl, S. B. Ong, and S. Richardson. 1999. Optimisation of electroporation for biochemical experiments in live cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 256:235--239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quaiser, A., F. Constantinesco, M. F. White, P. Forterre, and C. Elie. 2008. The Mre11 protein interacts with both Rad50 and the HerA bipolar helicase and is recruited to DNA following gamma irradiation in the archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. BMC Mol. Biol. 9:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richards, J. D., L. Cubeddu, J. Roberts, H. Liu, and M. F. White. 2008. The archaeal XPB protein is a ssDNA-dependent ATPase with a novel partner. J. Mol. Biol. 376:634--644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rolfsmeier, M., C. Haseltine, E. Bini, A. Clark, and P. Blum. 1998. Molecular characterization of the alpha-glucosidase gene (malA) from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Bacteriol. 180:1287--1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rolfsmeier, M. L., and C. A. Haseltine. 2010. The single-stranded DNA binding protein of Sulfolobus solfataricus acts in the presynaptic step of homologous recombination. J. Mol. Biol. 397:31--45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rouillon, C., and M. F. White. 2010. The XBP-Bax1 helicase-nuclease complex unwinds and cleaves DNA: implications for eukaryal and archaeal nucleotide excision repair. J. Biol. Chem. 285:11013--11022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sancar, A. 1996. DNA excision repair. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65:43--81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sancar, A. 2003. Structure and function of DNA photolyase and cryptochrome blue-light photoreceptors. Chem. Rev. 103:2203--2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schelert, J., M. Drozda, V. Dixit, A. Dillman, and P. Blum. 2006. Regulation of mercury resistance in the crenarchaeote Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Bacteriol. 188:7141--7150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt, K. J., K. E. Beck, and D. W. Grogan. 1999. UV stimulation of chromosomal marker exchange in Sulfolobus acidocaldarius: implications for DNA repair, conjugation and homologous recombination at extremely high temperatures. Genetics 152:1407--1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmittgen, T. D., and K. J. Livak. 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 3:1101--1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seitz, E. M., J. P. Brockman, S. J. Sandler, A. J. Clark, and S. C. Kowalczykowski. 1998. RadA protein is an archaeal RecA protein homolog that catalyzes DNA strand exchange. Genes Dev. 12:1248--1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seitz, E. M., and S. C. Kowalczykowski. 2000. The DNA binding and pairing preferences of the archaeal RadA protein demonstrate a universal characteristic of DNA strand exchange proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 37:555--560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.She, Q., R. K. Singh, F. Confalonieri, Y. Zivanovic, G. Allard, M. J. Awayez, C. C. Chan-Weiher, I. G. Clausen, B. A. Curtis, A. De Moors, G. Erauso, C. Fletcher, P. M. Gordon, I. Heikamp-de Jong, A. C. Jeffries, C. J. Kozera, N. Medina, X. Peng, H. P. Thi-Ngoc, P. Redder, M. E. Schenk, C. Theriault, N. Tolstrup, R. L. Charlebois, W. F. Doolittle, M. Duguet, T. Gaasterland, R. A. Garrett, M. A. Ragan, C. W. Sensen, and J. Van der Oost. 2001. The complete genome of the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus P2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:7835--7840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheng, D., M. Li, J. Jiao, J. Ni, and Y. Shen. 2008. Co-expression with RadA and the characterization of stRad55B, a RadA paralog from the hyperthermophilic crenarchaea Sulfolobus tokodaii. Sci. China C Life Sci. 51:60--65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheng, D., S. Zhu, T. Wei, J. Ni, and Y. Shen. 2008. The in vitro activity of a Rad55 homologue from Sulfolobus tokodaii, a candidate mediator in RadA-catalyzed homologous recombination. Extremophiles 12:147--157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White, M. F. 2009. Structure, function and evolution of the XPD family of iron-sulfur-containing 5′′→→3′′ DNA helicases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37:547--551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiseman, H., and B. Halliwell. 1996. Damage to DNA by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: role in inflammatory disease and progression to cancer. Biochem. J. 313:17--29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong, J. H., J. A. Brown, Z. Suo, P. Blum, T. Nohmi, and H. Ling. 2010. Structural insight into dynamic bypass of the major cisplatin-DNA adduct by Y-family polymerase Dpo4. EMBO J. 29:2059--2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wood, E. R., F. Ghane, and D. W. Grogan. 1997. Genetic responses of the thermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius to short-wavelength UV light. J. Bacteriol. 179:5693--5698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Worthington, P., V. Hoang, F. Perez-Pomares, and P. Blum. 2003. Targeted disruption of the alpha-amylase gene in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Bacteriol. 185:482--488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang, S., X. Yu, E. M. Seitz, S. C. Kowalczykowski, and E. H. Egelman. 2001. Archaeal RadA protein binds DNA as both helical filaments and octameric rings. J. Mol. Biol. 314:1077--1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.