Abstract

The linear cationic amphiphilic EB peptide, derived from the FGF4 signal sequence, was previously shown to be virucidal and to block herpes simplex type I (HSV-1) entry (H. Bultmann, J. S. Busse, and C. R. Brandt, J. Virol. 75:2634–2645, 2001). Here we show that cells treated with EB (RRKKAAVALLPAVLLALLAP) for less than 5 min are also protected from infection with HSV-1. Though protection was lost over a period of 5 to 8 h, it was reinduced as rapidly as during the initial treatment. Below a 20 μM concentration of EB, cells gained protection in a serum-dependent manner, requiring bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a cofactor. Above 40 μM, EB coprecipitated with BSA under hypotonic conditions. Coprecipitates retained antiviral activity and released active peptide. NaCl (≥0.3 M) blocked coprecipitation without interfering with antiviral activity. As shown for β-galactosidase, EB below 20 μM acted as an enzyme inhibitor, whereas above 40 to 100 μM EB, β-galactosidase was precipitated as was BSA or other unrelated proteins. Pyrene fluorescence spectroscopy revealed that in the course of protein aggregation, EB acted like a cationic surfactant and self associated in a process resembling micelle formation. Both antiviral activity and protein aggregation did not depend on stereospecific EB interactions but depended strongly on the sequence of the peptide's hydrophobic tail. EB resembles natural antimicrobial peptides, such as melittin, but when acting in a nonspecific detergent-like manner, it primarily seems to target proteins.

The EB peptide consists of the membrane-translocating hydrophobic or h sequence of the FGF4 signal peptide (25), with an N-terminal RRKK sequence added to improve solubility. EB was intended to be used as a cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) (23) for carrying antivirals into host cells but proved to be an effective broad-spectrum antiviral agent, inhibiting infections with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) (6), influenza virus (19), and vaccinia virus (1). EB seemed to primarily inactivate virions and block entry but was not active in pretreated host cells. In contrast, we had shown that another antiviral CPP, a modified TAT peptide (TAT-C) derived from the protein transduction domain of the HIV-1 TAT protein, not only inactivated virions but also protected pretreated cells from HSV-1 infection (7). We now show that EB has essentially the same prophylactic effect on host cells as the TAT-C peptide provided bovine serum albumin (BSA) is present as a cofactor.

As a linear cationic amphiphilic peptide, EB resembles natural antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), which act as antifungal, antibacterial, and antiviral agents. Natural AMPs are part of the innate immune system of plants, animals, and humans and are expected to become a rich source of novel antibiotics (14, 46, 47). About 1,000 eukaryotic AMPs have been isolated so far (42), and many derivatives have been synthesized in attempts to improve their pharmacological properties. Similar peptides are found in prokaryotes and in various animal venoms. Also, certain neuropeptides and neurohormones are structurally and functionally related to AMPs (4). Considering the structural resemblance, EB might also be expected to function like an AMP.

AMPs such as magainin 2 from frog skin are best known as membrane-active agents forming channels or pores (8, 28, 45). In interactions with model membranes, magainin 2 initially binds to the interface of the lipid bilayer parallel to the surface. Further binding above a critical threshold concentration occurs perpendicular to the surface with the formation of toroidal pores, 2 to 3 nm in diameter. Such pores are also formed in bacteria, whereas much larger pores (>23 nm) are formed in animal cells, such as CHO cells (18). Presumably, formation of the larger pores involves an alternative mechanism consistent with the carpet model of membrane lysis (18, 32). Pore formation promotes peptide internalization (28) and thus allows for direct interference of AMPs with intracellular processes, such as vital enzymes (e.g., see references 9 and 22) or the induction of mitochondrion-dependent apoptosis (24). Independent of their cytotoxic effects, AMPs may also act as chemoattractants for various leukocytes, providing a link between the innate and adaptive immune systems (11). Despite their diverse antimicrobial activities, which may be combined in a single peptide (e.g., nisin) (43), AMPs usually do not include proteins among their primary targets. This is consistent with the view that the evolution of the innate host defense system has favored low-affinity interactions with universal nonprotein targets as a strategy of evading bacterial resistance (35).

As we examined possible mechanisms of EB-BSA interactions leading to cellular protection from infection, we discovered that EB did not conform to typical activity patterns of natural AMPs but interacted with proteins in a detergent-like manner. The effects of detergents on proteins vary considerably depending on the type of surfactant and the nature of the protein. For example, α-lactalbumin (α-LA) is maximally denatured by ionic detergents, such as sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) or tetradecyl trimethyl ammonium chloride (TTAC), at saturating submicellar concentrations corresponding to residue/detergent ratios of 2.9 and 3.4, respectively (34). α-LA is also denatured by zwitterionic (di-heptanoyl-phosphatidyl chlorine) and nonionic detergents (decyl maltoside), but only above the critical micelle concentration (CMC) and residue/detergent ratios of 6 and 7, respectively (34). SDS also must reach the CMC before detergent-resistant β-sheet proteins are unfolded (30). Furthermore, protein denaturation is affected by the size and shape of SDS micelles (33).

Reduced BSA, like α-LA, is maximally denatured at submicellar concentrations of both anionic (SDS) and cationic (TTAC) detergents at residue/detergent ratios of ≤2 and 3.3, respectively (31, 36). But unlike α-LA, BSA is not denatured by zwitterionic (deoxycholate) or nonionic detergents (Triton X-100) (27). BSA, in its native state, is unusual in that it has high-affinity binding sites for each of the four types of surfactants: 10 or 11 for SDS and 4 each for TTAC, deoxycholate, and Triton X-100. The existence of such specific binding sites is related to the major biological function of BSA as a carrier of fatty acids in the circulatory system (15). Serum albumin is also an effective scavenger of a great variety of peptides, which may become useful serum biomarkers of early disease detection (26) and whose pharmacokinetic properties may be greatly improved in association with serum albumin (10). We found that EB peptides behave like a cationic surfactant that can self associate in a micelle-like manner and aggregate BSA and other unrelated proteins.

In conclusion, we have shown that EB peptides can protect host cells from HSV-1 infection provided BSA is present as a cofactor. We have also shown that these peptides interact with proteins in a sequence-specific detergent-like manner. Peptide-induced protein aggregation seems to be important for virucidal and cytotoxic effects but is not an obligatory requirement for protecting cells from viral infection, suggesting that more-subtle interactions play a role. Though detergent-like interactions of linear cationic amphiphilic peptides with membranes have been studied extensively (for a review, see reference 3), detergent-like interactions of these peptides with proteins have remained unexplored. Such interactions with proteins are of considerable interest in defining the antimicrobial and broader pharmacological properties of such peptides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and virus.

Vero cells (African Green Monkey kidney cells; ATCC CLL-81) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% calf serum, 5% fetal bovine serum, 0.06 g/liter penicillin G, and 0.08g/liter streptomycin sulfate. Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were maintained as described previously (19). Primary human foreskin fibroblasts were cultured like Vero cells except that DMEM was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The HSV-1 hrR3 mutant expressing Escherichia coli β-galactosidase from the ICP6 promoter (12) was used for all experiments.

Peptides and proteins.

Synthesis, purification (to >90%), and analysis of peptides were done at the Biotechnology Center at the University of Wisconsin—Madison as described previously (6), except for the EBd° peptide, which was supplied by Bachem California Inc. (Torrance, CA) at a purity of >98%. Table 1 shows the sequences of the peptides used in this study. The TAT-Cd− peptide was partially dimerized, but peptide concentrations refer to monomeric peptide. Bovine serum albumin (A2153), soybean trypsin inhibitor (T9003), and Escherichia coli β-galactosidase (G5635) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Dimeric human fibronectin (FN) was a gift from Donna Peters, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Wisconsin—Madison.

TABLE 1.

Peptides used in this work

| Peptidea | Sequenceb |

|---|---|

| EB | NH2-RRKKAAVALLPAVLLALLAP-COOH |

| bEB | b-RRKKAAVALLPAVLLALLAP-COOH |

| EBd− | NH2-RRKKAAVALLPAVLLALLAP-COOH |

| EBd° | NH2-RRKKAAVALLPAVLLALLAP-CONH2 |

| EBX | NH2-RRKKLAALPLVLAAPLAVLA-COOH |

| TAT-Cd− | NH2-GRKKRRQRRRC-COOH |

Superscripts indicate whether the C terminus bears a carboxyl group (−) or an amide (0).

Amino acid sequences are given in single-letter code. Boldface type indicates charged residues. Underlining indicates d-enantiomers. The “b-” superscript indicates replacement of the amino group with biotin-aminohexanoyl.

Acquisition of cellular protection from viral infection.

Confluent Vero cell cultures in 96-well plates (2 × 105 cells/well) were switched to antibiotic-free and bicarbonate-free DMEM buffered with 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) for the duration of the experiment. Thirty minutes later, cells were exposed to EB or other peptides in 40 μl of medium for 1 h at 37°C. Peptides were removed by rinsing the cultures three times, and cells were infected with hrR3 in 40 μl of 10% serum-supplemented medium for 1 h at 37°C. The infection was terminated by treating cultures for 60 s with citrate buffer (pH 3) between two rinses with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (0.14 M NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, and 10 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.3). Cells treated with EB in serum-free DMEM were allowed to adapt to that medium for 30 min at 37°C before peptide was added. Cells treated with EBd− for just 10 min at 37°C were plated in poly-l-lysine-coated wells (P4707; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and directly switched from regular culture medium to PBS containing 1% BSA and peptide.

Infectivity was measured by scoring cells stained with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) 8 h after infection. Alternatively, cell lysates were prepared 6 h after infection, and viral β-galactosidase activity was determined after adding the chlorophenol red-β-d-galactopyranoside (CPRG) substrate (Roche Diagnostics Gmbh, Mannheim, Germany) by measuring initial rates of color development at 570 nm in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader (6). X-Gal-stained cells were infected at an a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of ∼0.05. The β-galactosidase assay was done with cultures infected at an MOI of ≤0.01 to ensure that infectivity was linearly related to enzymatic activity.

Cell viability was measured in uninfected Vero cells by trypan blue exclusion or by the MTS assay (catalog no. G3580; Promega Co., Madison WI). In the latter case, following various treatments, cultures at ∼6 × 104 cells/well were exposed to 6-fold-diluted MTS tetrazolium reagent in 10% serum-supplemented DMEM for 90 min at 37°C. Cells were lysed in 0.5% Igepal CA-630 detergent (catalog no. I-3021; Sigma Chem. Co., St. Louis, MO) in PBS, and absorbance readings were taken at 490 nm.

EB-induced protein aggregation.

Various proteins at a concentration of 0.3 mg/ml in PBS or in 10 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 7) or 10 mM HEPES (pH 7) buffers containing increasing amounts of NaCl were exposed to different amounts of EB peptides for 10 to 80 min at ∼23°C. Any turbid material formed during this time was kept suspended by frequent shaking and Vortex treatments, or it was pelleted by low-speed centrifugation. After serial dilution, absorbance readings were taken at wavelengths of 280 and 320 nm. Absorbance readings prior to peptide addition were subtracted (except for the data shown in Fig. 4A).

Preparation and HPLC analysis of a BSA-EB coprecipitate.

BSA (0.3 mg/ml) and EB (400 μM) were incubated in 300 μl hypotonic phosphate buffer (10 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7) for 15 min at ∼23°C, and the resulting precipitate was collected by centrifugation and solubilized in 10 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 7) containing 0.5 M NaCl. The redissolved pellet material and the cleared supernatant were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Samples were injected into a 5-μm Vydac C18 4.6- by 150-mm column equilibrated with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water. BSA and EB were eluted in the presence of 0.08% trifluoroacetic acid by increasing the acetonitrile concentration from 25 to 60% over a period of 35 min. BSA was recognized by absorbance readings at 215 and 280 nm, whereas the EB peptide lacking tryptophan and tyrosine residues was seen only at 215 nm.

Preparation, cross-linking, and antiviral activity of a BSA-EBd coprecipitate.

BSA (3 mg/ml) and EBd− (400 μM) were coprecipitated in 800 μl isotonic phosphate buffer (0.15 M NaCl in 10 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.4) for 30 min at 37°C. The precipitate was twice pelleted and resuspended by sonication in HEPES-buffered DMEM containing 3 mg/ml BSA. Half of the first suspension was treated for 30 min at 37°C with a cross-linker [1 mM BS3; bis(sulfosuccinimidyl) suberate; no. 21579; Pierce, Rockford, IL]. The cross-linker was inactivated for 15 min at ∼23°C by adding Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) to 20 mM. The rest of the material was mock treated. Aliquots of the final suspensions were tested directly for antiviral activity or they were first allowed to release peptide for 1 h at 37°C. The released peptide was separated from the residual complex by centrifugation. Both suspensions and cleared supernatants were serially diluted and added to Vero cells for 1 h at 37°C prior to infection with hrR3.

Inhibition of enzymatic activity of β-galactosidase.

The commercially available enzyme was reconstituted in 10 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 7.4) containing 2 mM MgCl2, and enzyme activity was measured without (hypotonic buffer) or with (hypertonic buffer) the addition of 0.3 M NaCl. Enzyme activity was also measured in isotonic PBS containing 0.5% octylphenoxy-polyethoxyethanol detergent (Igepal CA-630). The enzymatic activity of hrR3-infected Vero cells was measured in cell lysates prepared in the same buffer 6 h after infection. Reconstituted enzyme was exposed to peptide for 20 min at ∼23°C before a substrate (CPRG) was added, and the initial (linear) increase in absorbance was measured at 570 nm in an ELISA reader. The final concentration of the reconstituted enzyme was 0.04 μg/ml (1,000 U/mg protein) after addition of substrate to a final concentration of 5 mM in a total volume of 100 μl.

Pyrene probe fluorescence spectroscopy.

The EB, EBX, and EBd° peptides, at concentrations between 0.3 and 3,000 μM, were dissolved in hypertonic buffer (0.3 M NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.4), and pyrene (82648; Fluka Analytical, St. Louis, MO) was added to a final concentration of 2 μM from a 2 mM stock solution in n-hexane. Approximately 20 min later, excitation and emission fluorescence spectra were recorded with an Aminco-Bowman series 2 luminescence spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corp., Madison, WI) using a 1-mm by 10-mm dual-path-length Spectrosil quartz cuvette (53-Q-1; Starna Cells Inc., Atascadero, CA). The pyrene probe emission spectra were scanned from 360 nm to 420 nm at a scan rate of 0.2 nm/s. The emission monochromator step size was set to 0.2 nm with a band-pass of 4 nm. The excitation wavelength was 310 nm, with a 4-nm band-pass. The pyrene probe excitation spectra were scanned from 300 nm to 360 nm at a scan rate of 0.2 nm/s. The excitation monochromator step size was set to 0.2 nm, with a band-pass of 4 nm. The emission wavelength was 390 nm, with a 4-nm band-pass.

Binding studies with biotinylated EB.

Peptide binding to live Vero cells or immobilized heparin was done with bEB (Table 1), which was 2- to 3-fold less effective in protecting cells from HSV-1 infection than the nonbiotinylated peptide (data not shown). Binding to live cells was carried out for 1 h at 4°C in 10% serum-supplemented DMEM buffered with 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.3). Cells were then rinsed with peptide-free medium containing up to 0.5 M NaCl and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in serum-free medium for 10 min at 4°C. Binding to immobilized heparin was carried out for 30 min at 4°C in serum-free medium, followed by rinses with serum-supplemented medium containing up to 2 M NaCl. In all cases, bound peptide was detected with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (016-050-084; Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs Inc., West Grove, PA) in an ELISA. Heparin (H93990; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was immobilized on methyl vinyl ether-maleic anhydride-coated Costar 9102 strip-well microtiter plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) treated with adipic acid dihydrazide (37).

RESULTS

EB protects cells from HSV-1 infection in a serum-dependent manner.

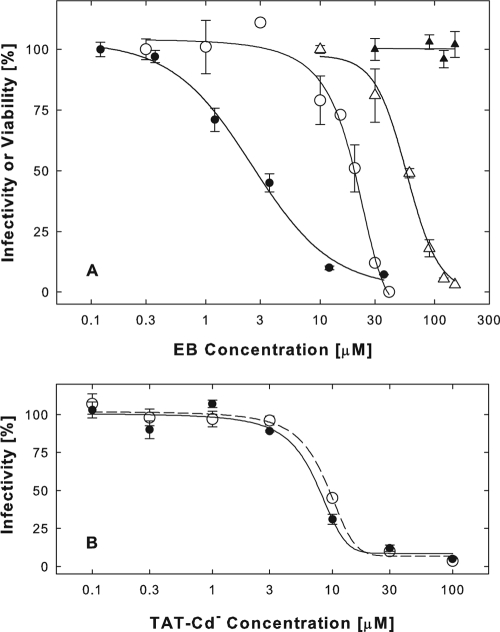

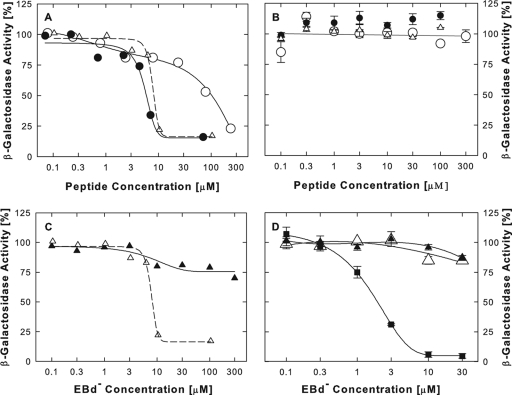

We had previously shown that the EB peptide at concentrations of 1 to 10 μM was an HSV-1 entry blocker that did not interfere with virus adsorption but directly and irreversibly inactivated virions (6). We also concluded that cellular effects of this peptide made little or no contribution to antiviral activity. In these studies, cultures were pretreated with EB in serum-free medium prior to infection with hrR3 virus in peptide-free medium. Under these conditions, EB blocked infection only at relatively high concentrations (Fig. 1A, ○) (50% effective concentration [EC50] = 20 μM), which also compromised cell viability (Fig. 1A, ▵) (EC50 = 55 μM). In subsequent studies where cells were exposed to EB in the presence of serum, we found that antiviral and cytotoxic effects were readily dissociated, showing that EB could effectively protect cells from HSV-1 infection.

FIG. 1.

EB protects cells from HSV-1 infection in a serum-dependent manner. (A) Confluent Vero cell cultures (2 × 105 cells/well) were serum deprived for 30 min and then exposed to EB for 1 h at 37°C in serum-free DMEM (○ and ▵) or in DMEM supplemented with 10% serum (• and ▴). The peptide was rinsed off, and cultures were infected with 1,200 PFU/well hrR3 for 1 h at 37°C in the presence of 10% serum. The infection was terminated with citrate buffer (pH 3), and 6 h later, infectivity was measured as the initial rate of viral β-galactosidase activity in cell lysates (• and ○). Cell viability was measured in EB-treated uninfected cells by the MTS assay (▴ and ▵). (B) For comparison, TAT-Cd− was tested for antiviral activity in serum-free (○) or 10% serum-supplemented (•) DMEM in the same experiment described for panel A. IC50s were indistinguishable and were close to 8 μM in this and additional experiments. All points are means of triplicate determinations with standard errors of the means.

The addition of 10% serum enhanced the antiviral activity of EB during cell pretreatments about 10-fold (Fig. 1A, •) (EC50 = 2.7 μM; range, 1 to 4 μM) and eliminated all cytotoxic effects (Fig. 1A, ▴). EBX, a modified version of EB with a scrambled hydrophobic sequence (RRKKLAALPLVAAPLAVLA), was an 8-fold less effective antiviral agent in this assay (data not shown), indicating that EB protected cells in a sequence-specific manner. The ability to acquire protection from HSV-1 infection in response to EB was not a cell-type-specific property. Thus, Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells or human primary fibroblasts were protected in the same way as Vero cells (data not shown). Cell pretreatments with EB in serum-supplemented medium were as effective as virucidal treatments, in which virions were exposed to EB for 1 h at 37°C in serum-free medium before they were added to cells in the presence of peptide (EC50 = 1.7 μM; data not shown). Furthermore, cell pretreatments with EB and serum were as effective as pretreatments with a TAT-C peptide, which, in contrast to EB, inhibited virus infection in a serum-independent manner (Fig. 1B). In other ways, however, the cellular effects of EB were nearly indistinguishable from the cellular effects previously described for TAT-C peptides (7).

Acquisition, loss, and reinduction of cellular protection from infection.

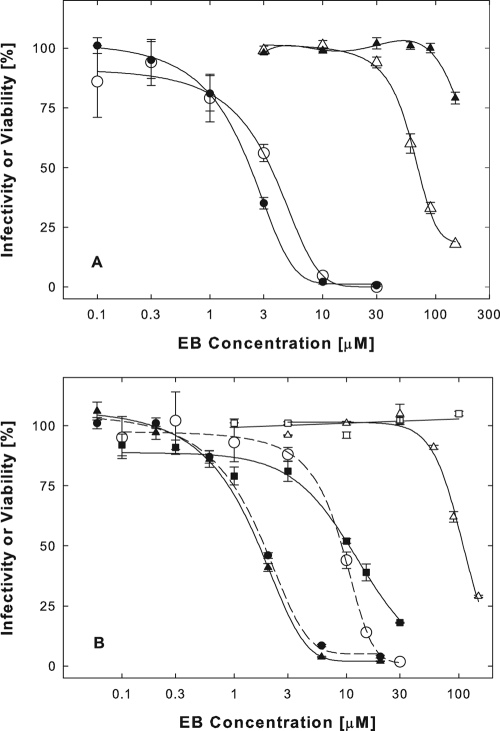

Cells exposed to EB acquired protection from viral infection rapidly. Within 5 min, 30 μM EB reduced infectivity by 75% (Fig. 2A, •). EBX acted more slowly and less efficiently (Fig. 2A, ○). Following cell pretreatments, peptides were efficiently rinsed off, since exposures to peptides for just a few seconds at ∼23°C had little or no antiviral effect (zero time points).

FIG. 2.

Acquisition, loss, and reinduction of cellular protection from infection. (A) Rapid acquisition of cellular protection. Vero cells plated in a strip well plate (2 × 105 cells/well) were exposed to 30 μM EB (•) or EBX (○) at 37°C for the times indicated. The peptides were then rinsed off, and cells were infected with untreated virus (8,400 PFU/well hrR3) in the absence of peptide for 1 h at 37°C. Without any pretreatment, cells retained 100% infectivity throughout the experiment (data not shown). Zero time points represent cultures pretreated with peptides for <1 min at ∼23°C. (B) Slow loss of cellular protection under normal growth conditions. Vero cells plated in a strip well plate (2 × 105 cells/well) were pretreated with 30 μM EB (▴) or without peptide (○) for 1 h at 37°C. Cultures were rinsed and kept in normal culture medium for the indicated times before they were infected with untreated hrR3 (8,400 PFU/well) in the absence of peptide. (C) Repeated induction of cellular protection. Vero cells (2 × 105 cells/well) were exposed to the indicated concentrations of EB for 1 h at 37°C. The peptide was rinsed off, and cultures were infected in the absence of peptide with untreated hrR3 (9,100 PFU/well) immediately thereafter (•) or 8.5 h later following an incubation in peptide-free normal culture medium (○). Additional cultures were also infected following a second pretreatment of cells with EB 8.5 h after the first exposure (▵). LacZ+ cells were scored after X-Gal staining as described in the legend to Fig. 1. All points are means of triplicate determinations with standard errors of the means.

Protected cells regained susceptibility to infection slowly, indicating that cellular effects of EB were not readily reversible. Under normal culture conditions, it took 2 h for cells to lose 50% of the EB-induced protection and 5 to 8 h to lose all protection (Fig. 2B, ▴).

Cellular protection could be reinduced after cells regained normal susceptibility to infection following an earlier peptide treatment. For example, as shown in Fig. 2C, immediately following a first exposure to EB, cells had acquired protection at an EC50 of 4 μM (•) and had lost most of that protection 8.5 h later (○). At that point, parallel cultures were treated at the same EB concentrations for a second time. Immediately following the second exposure to peptide, cells had regained protection at an EC50 of 2.5 μM (▵), indicating that the cellular response to EB was fully restored.

In conclusion, the antiviral activity of EB was not restricted to virucidal effects but, as in the case of TAT-C peptides, included additional interactions with one or more cellular targets required for infection. But unlike TAT-C peptides, EB protected cells in a serum-dependent manner.

BSA as a cofactor of antiviral activity of EB.

Addition of 3% BSA to serum-free DMEM during pretreatments of cells with EB enhanced antiviral activity (Fig. 3A, •) (EC50 = 2.3 μM) and cell viability (Fig. 3A, ▴) in nearly the same way as did the addition of 10% serum. At a 10-fold-lower BSA concentration (0.3%), corresponding to the albumin concentration in the serum-supplemented medium, EB remained an effective antiviral (Fig. 3A, ○) (EC50 = 3.3 μM), though cell viability was improved very little (Fig. 3A, ▵) (EC50 = 71 μM).

FIG. 3.

BSA is a specific cofactor in the antiviral activity of EB. (A) BSA can substitute for the serum requirement of EB. Vero cells were pretreated with EB in serum-free DMEM supplemented with either 0.3% (○ and ▵) or 3% (• and ▴) BSA, and the effects on hrR3 infectivity (○ and •) and cell viability (▵ and ▴) were measured. (B) Trypsin inhibitor cannot substitute for the serum requirement of EB. Vero cells were pretreated with EB in serum-free DMEM (○) or in DMEM supplemented with 1% soybean trypsin inhibitor (▪ and □), 1% BSA (▴ and ▵), or 10% serum (•), and the effect on hrR3 infectivity (○, ▪, ▴, and •) and cell viability (□ and ▵) were measured. Other details are as described in the legend to Fig. 1. All points are means of triplicate determinations with standard errors of the means.

To test whether another protein could substitute for BSA, we compared the antiviral activities of EB during cell pretreatments in serum-free DMEM supplemented with either 1% soybean trypsin inhibitor or 1% BSA. Again, the addition of BSA enhanced antiviral activity equivalently to the addition of 10% serum (Fig. 3B, ▴ [EC50 = 1.7 μM] versus • [EC50 = 1.9 μM]). In the presence of the trypsin inhibitor, EB was no more effective than in serum-free medium (Fig. 3B, ▪ [EC50 = 12 μM] versus ○ [EC50 = 9.2 μM]) despite the fact that cell viability was enhanced more by trypsin inhibitor than by BSA (Fig. 3B, □ versus ▵).

BSA thus accounts for the serum requirement of EB-induced cellular protection from viral infection. The possibility that EB might directly interact with a serum component such as BSA was initially suggested by the observation that the addition of concentrated EB solutions to serum-containing medium was always accompanied by the transient appearance of precipitates. We investigated this phenomenon by measuring optical changes resulting from the addition of EB to BSA-containing buffer solutions.

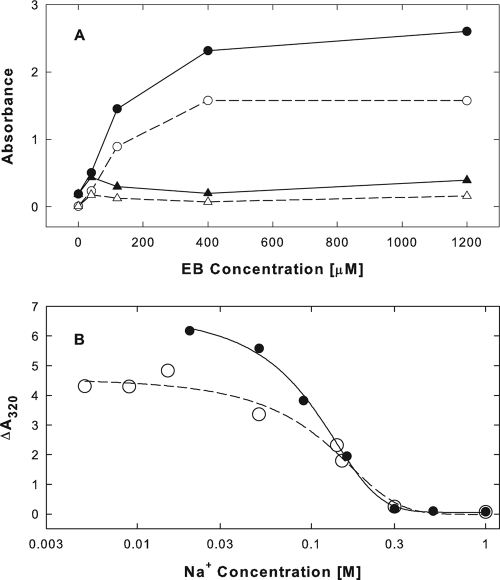

EB-induced BSA aggregation.

When EB was added to BSA in isotonic phosphate buffer (pH 7), absorbance readings at 280 or 320 nm increased dramatically (Fig. 4A, • and ○, respectively). After removal of the turbid material by centrifugation, absorbance readings at 280 and 320 nm were reduced to near-background levels (Fig. 4A, ▴ and ▵, respectively). At an input of 0.3 mg/ml or 4.5 μM BSA, saturation was reached near 400 μM EB or at an EB/BSA molar ratio of 89. Most of the absorbance changes (70%) occurred within less than 2 min. Thereafter, the reaction continued at much reduced rates for at least 2 h (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

EB mediates BSA aggregation. (A) EB-induced absorbance changes in BSA under isotonic conditions. BSA (0.3 mg/ml or 4.5 μM in PBS; pH 7) was exposed to increasing concentrations of EB for 10 min at ∼23°C. Aliquots were removed and serially diluted for absorbance readings at wavelengths of 280 nm (• and ▴) or 320 nm (○ and ▵). Absorbance readings were taken before (• and ○) and after (▴ and ▵) removal of turbidities by centrifugation. (B) Dependence of EB-induced absorbance changes in BSA on ionic conditions. BSA (0.3 mg/ml) dissolved in 10 mM Na2HPO4 buffer (pH 7; •) or 10 mM HEPES (pH 7; ○) was exposed to 400 μM EB and increasing concentrations of NaCl for 80 min at ∼23°C. The increase in turbidity in serially diluted aliquots was measured at 320 nm and plotted as a function of the calculated sodium ion concentrations.

EB-BSA interactions resulting in absorbance changes were strongly dependent on sodium ion concentrations (Fig. 4B). They were stimulated by hypotonic conditions but were completely prevented at sodium ion concentrations of ≥0.3 M. Anionic conditions also affected EB-BSA interactions primarily below physiological sodium ion concentrations (compare the effects of phosphate [•] and HEPES [○] buffers in Fig. 4B). The precipitates formed under hypotonic or isotonic conditions were only partially soluble in hypertonic solutions. Typically, only ∼50% of the precipitate was dissolved again in a buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl, and any further increase in the NaCl concentration to 1 or 2 M had no effect (data not shown).

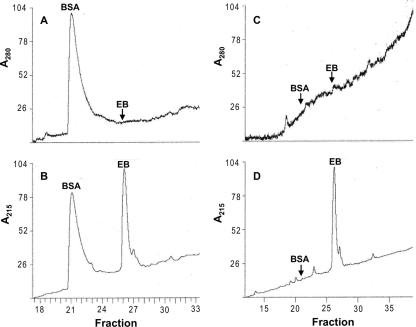

EB and BSA coprecipitated under hypotonic conditions. The EB and BSA recovered from the pelleted material in hypertonic buffer were readily separated by HPLC and detected by absorbance readings at 215 nm (Fig. 5B). As expected, no EB was detected at a wavelength of 280 nm (Fig. 5A and C). The supernatant remaining after the removal of the precipitate was completely depleted of BSA (Fig. 5C and D) but still retained 20% of the EB, as determined from calibrations of peak areas (Fig. 5D). The protein was therefore quantitatively removed by an excess of peptide. Given the starting concentrations of EB (400 μM) and BSA (4.5 μM), we obtained an EB/BSA molar ratio of 71 for the coprecipitate formed under hypotonic conditions, comparable to the estimate obtained spectrophotometrically under isotonic conditions (EB/BSA = 89) (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 5.

Analysis of BSA-EB coprecipitates by HPLC. A coprecipitate of BSA and EB formed in hypotonic buffer was collected by centrifugation and solubilized in 0.5 M NaCl. Aliquots of the solubilized pellet material (A and B) and the cleared supernatant (C and D) were analyzed by HPLC. Absorbance readings were taken at 280 (A and C) (BSA signal only) and 215 nm (B and D) (BSA and EB signals). Peaks or peak positions (arrows) were identified by comparison with BSA and EB reference solutions. In each panel, maximal absorbance readings were arbitrarily set to 100%.

Specificity of peptide-protein interactions.

Proteins completely unrelated to BSA responded to EB in nearly the same fashion. For example, when equal amounts (0.3 mg/ml) of soybean trypsin inhibitor or dimeric human fibronectin were exposed to EB in isotonic phosphate buffer, absorbance readings at 280 and 320 nm increased and reached a plateau at the same EB concentrations as for BSA (data not shown). This suggested that each of the three proteins was completely precipitated at the same peptide concentration, corresponding to 1 EB molecule for every 6 to 7 amino acid residues in the proteins or a residue/EB ratio of ≤7. The three proteins also did not differ markedly in the minimal EB concentration required to initiate absorbance changes. Thus, EB appears to precipitate proteins in a general manner.

We also tested modified EB peptides for their ability to induce absorbance changes in BSA dissolved in hypotonic buffer (20 mM NaCl). In this case, plateau levels were not reached even at peptide concentrations as high as 1,100 μM. More importantly, the absorbance increase elicited by an EB peptide composed entirely of dextral d-amino acids (EBd−) was the same as that for EB (data not shown), indicating that chirality was of little or no consequence in EB-protein interactions. In contrast, two other peptides (EBX and TAT-Cd−; data not shown) at concentrations as high as 800 mM had no effect on BSA absorbance.

The inability of EBX to precipitate BSA suggests that EB-protein interactions did not depend on some general physical properties shared by EB and EBX, i.e., a cluster of four positively charged residues tagged to a tail of 16 strictly hydrophobic residues. Instead, such interactions must specifically depend on the sequence of the hydrophobic amino acids. The N-terminal cluster of arginines and lysines seems to be less important, at least by itself, as suggested by the finding that the TAT-Cd− peptide, composed almost entirely of positively charged amino acids, did not induce any absorbance changes in BSA.

Antiviral activity of EB-BSA coprecipitates.

EB peptides when complexed with BSA did not lose their antiviral activity. When an EBd−-BSA coprecipitate formed in isotonic buffer was resuspended by sonication and added to cells for 1 h at 37°C before exposure to hrR3, infection was completely prevented (Fig. 6A, •). Treatment of the coprecipitate with a cross-linking agent (BS3) abolished the antiviral activity (Fig. 6A, ○), indicating that the precipitate was nontoxic and that antiviral activity depended on the release of peptide. The release of peptide was directly demonstrated by incubating the coprecipitate in isotonic buffer for 1 h at 37°C, removing the residual precipitate by centrifugation, and testing the supernatant for antiviral activity (Fig. 6B, •). No peptide was released from the cross-linked complex (Fig. 6B, ○). Comparing the EC50s, we estimated that the activities of the undiluted complex and the undiluted released peptide were equivalent to EBd− concentrations of 250 and 95 μM, respectively. Thus, the EBd−-BSA complex functioned as an effective peptide carrier.

FIG. 6.

Antiviral activity of BSA-EBd− coprecipitates. A BSA-EBd− coprecipitate, resuspended by sonication (A) (•), and EBd− peptide released from such a complex over a period of 1 h at 37°C (B) (•) were serially diluted and added to cells for 1 h at 37°C before the cultures were rinsed and infected with hrR3. Infectivity was measured as β-galactosidase activity. Sample fractions required for blocking infection by 50% are marked by vertical dashed lines and correspond to a 27.8-fold (A) or 10.5-fold (B) sample dilution. Treatment of the BSA-EBd− coprecipitates with a cross-linking agent (BS3) abolished antiviral activity of the complex (A) (○) and prevented the released of peptide (B) (○).

Antiviral activity unrelated to BSA aggregation.

To test whether EB-BSA coaggregates were required for antiviral activity, we blocked BSA precipitation with 0.3 M NaCl (Fig. 4B). First, we established that cells can tolerate brief treatments (10 min at 37°C) with 0.3 M NaCl in PBS containing 1% BSA (Fig. 7A, ○) and that viral infectivity was minimally reduced (Fig. 7A, •). We also found that EBd− had no cytotoxic effects at concentrations up to 60 μM, regardless of whether 0.3 M NaCl was present (Fig. 7B, ▴ and ▵). Finally, we showed that nontoxic concentrations of EBd− induced cellular protection from infection regardless of the presence of 0.3 M NaCl (Fig. 7B, ○ and •), though less efficiently (EC50 = 15 to 18 μM) than under optimal conditions (see below) (Fig. 8D, ▪) (EC50 = 1.9 μM). The addition of 0.4 M NaCl also did not interfere with antiviral activity, but at 0.5 M NaCl, the EC50 increased about 4-fold. Essentially the same results were obtained with the EB peptide (data not shown). Since BSA aggregation was completely prevented by 0.3 M NaCl (Fig. 4B), we concluded that the ability of EB peptides to act as an antiviral agent was unrelated to their ability to act as an aggregation agent.

FIG. 7.

Antiviral activity unrelated to BSA aggregation. (A) Effects of hypertonic conditions on susceptibility to infection and cell viability in the absence of peptide. Vero cells (2 × 105 cells/well) plated on poly-l-lysine were exposed for 10 min at 37°C to increasing concentrations of NaCl in PBS containing 1% BSA. Cells were then rinsed and infected with hrR3 (MOI of ∼0.1) in DMEM containing 10% serum. The infection was terminated with citrate buffer (pH 3), and infectivity was measured as β-galactosidase activity 6 h later (•). Cell viability was measured in NaCl-treated uninfected cultures using the MTS assay (○). (B) Cellular protection from infection is not affected by 0.3 M NaCl. Following pretreatment for 10 min at 37°C at increasing EBd−concentrations with (• and ▴) or without (○ and ▵) addition of 0.3 M NaCl, cells were infected and β-galactosidase activity (• and ○) was measured as for panel A. Cell viability (▴ and ▵) was also measured as for panel A.

FIG. 8.

Inhibition of β-galactosidase activity by EB peptides. (A) Inhibition in hypotonic buffer. E. coli β-galactosidase (0.04 μg/ml) was exposed to increasing concentrations of EB (•), EBd− (▵), or EBX (○) for 20 min at ∼23°C in hypotonic buffer [2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Na2HPO4; pH 7.4). The CPRG substrate was added, and the initial rate of color development was measured at 570 nm using an ELISA reader. (B) No inhibition in isotonic lysates of hrR3-infected cells. Confluent Vero cells in a 96-well plate were infected with hrR3 (MOI of ∼0.05). Six hours later, cells were lysed with 0.5% Igepal CA-630 detergent in PBS. EB (•), EBd− (▵), or EBX (○) was added, and viral β-galactosidase activity was measured as described for panel A. (C) Comparison of different buffers. E. coli β-galactosidase (0.04 μg/ml) was exposed to increasing concentrations of EBd− for 20 min at ∼23°C in hypotonic buffer (data taken from panel A) (▵) or in isotonic lysing buffer (as for panel B) (▴). Enzymatic activity was measured as described for panel A. (D) In intact cells, EBd− inhibits virus entry but not the expression and activity of viral β-galactosidase. Confluent Vero cells in a 96-well plate were infected with hrR3 (MOI of ∼0.05), and 6 h later, initial rates of β-galactosidase activity were measured in cell lysates. EBd− was present in the culture medium for 1 h prior to infection (▪), or it was added at 1 h postinfection for periods of 1 h(▵) or 5 h (▴). Peptide was removed prior to lysis by rinsing cultures with peptide-free medium.

EB peptides as enzyme inhibitors.

We had initially dismissed the possibility that EB-mediated protein precipitation was related to antiviral activity simply because peptide concentrations inhibiting virus infection were at least 10-fold lower than precipitating concentrations (cf. Fig. 1 to 3 with Fig. 4A). To test whether low or high peptide concentrations might have distinctive effects on a single protein species, we examined the enzymatic activity of β-galactosidase in relation to β-galactosidase aggregation under various experimental conditions.

Under hypotonic conditions (20 mM Na+), EB inhibited the activity of Escherichia coli β-galactosidase with an EC50 of 5.8 μM (Fig. 8A, •), similar to the range of concentrations required to block HSV-1 infection by pretreating cells with the peptide (EC50 = 2 to 4 μM) (Fig. 1 to 3). EBd− seemed to be slightly less effective (EC50 = 8 μM; Fig. 8A, ▵), whereas EBX performed poorly (EC50 = 100 μM) (○). This is consistent with the earlier finding that EB functions were largely independent of chirality but strongly dependent on the sequence of hydrophobic residues.

Under isotonic conditions, in lysates of hrR3-infected Vero cells, the viral β-galactosidase (an E. coli β-galactosidase fusion protein) was not inhibited by any of the three peptides (Fig. 8B). This was unrelated to differences in the source of the enzyme, because commercially obtained β-galactosidase was severely inhibited by EBd− only in hypotonic medium (Fig. 8C, ▵) and not in the isotonic buffer used to prepare the cell lysates (Fig. 8C, ▴).

EBd− at concentrations up to 30 μM also had little or no effect on β-galactosidase expression and activity in intact cells, regardless of whether these cells were exposed to the peptide for 1 or 5 h after infection with hrR3 (Fig. 8D, ▵ and ▴). The activity of β-galactosidase was severely inhibited only if cells had been exposed to EBd− prior to infection (EC50 = 1.9 μM) (Fig. 8D, ▪). We infer that EBd−, like EB (6), acts as an entry blocker and that the β-galactosidase-based assay is a valid indicator of such activity because the expressed enzyme is not inhibited under standard assay conditions or in intact cells. Our finding that EB peptides are potential inhibitors of β-galactosidase is therefore not incompatible with conventional interpretations of enzyme-based entry data.

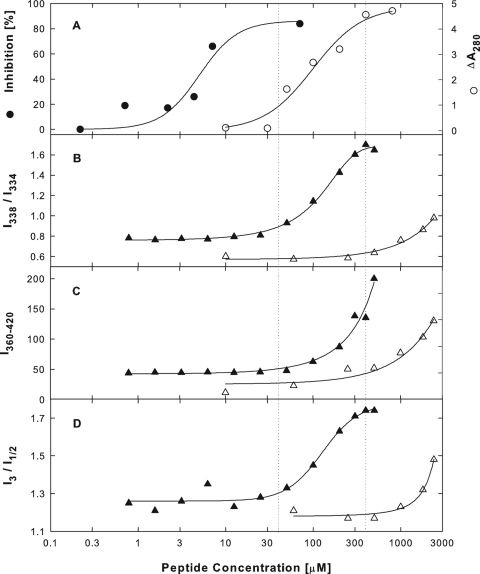

Aggregation of β-galactosidase in relation to peptide self association.

The aggregation of β-galactosidase in hypotonic buffer occurred at EB concentrations between 40 and 400 μM (Fig. 9A, ○), over the same range as the aggregation of BSA, FN, or trypsin inhibitor. Even though there was no overlap between aggregation and enzyme inhibition (Fig. 9A, ○ versus •), the EB concentration causing 50% aggregation (100 μM) was only 17 times higher than the EB concentration inhibiting the enzyme by 50% (5.8 μM). In contrast, the protein concentration employed in the aggregation assay (300 μg/ml) was 7,500 times higher than the protein concentration used in the enzyme assay (0.04 μg/ml). EB was therefore at least 400 times more efficient as an aggregation agent than as an enzyme inhibitor. One possible explanation could be that EB, like other amphiphilic compounds, might be rendered more efficient as an aggregation agent by forming micelles or vesicles.

FIG. 9.

Protein aggregation in relation to peptide self association. (A) β-Galactosidase aggregation in relation to the inhibition of enzymatic activity. Three hundred μg/ml β-galactosidase was exposed to increasing concentrations of EB in hypotonic buffer (2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.4) for 1 h at 20°C, and aliquots were removed and serially diluted for absorbance readings at 280 nm (○) (50% precipitation at 100 μM EB). For comparison, we also show the inhibitory effects of EB on the activity of 0.04 μg/ml β-galactosidase in the hypotonic buffer (EC50 = 5.8 μM; data from Fig. 8A) (•). (B to D) Self association of peptides. Self association was measured as a red shift in pyrene excitation spectra (I338/I334) (B), as a change in total pyrene emission fluorescence intensities at wavelengths between 360 and 420 nm (I360-420) (C), or as a change in the vibrational fine structure of pyrene emission fluorescence spectra, the maximal intensity at peak 3 relative to the minimal intensity between peaks 1 and 2 (I3/I1/2) (D) (peaks identified in Fig. 10). All spectra were obtained at 15°C from clear hypertonic solutions (2 mM MgCl2, 0.3 M NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.4) containing 2 μM pyrene and increasing concentrations of EB (▴) or EBX (▵).

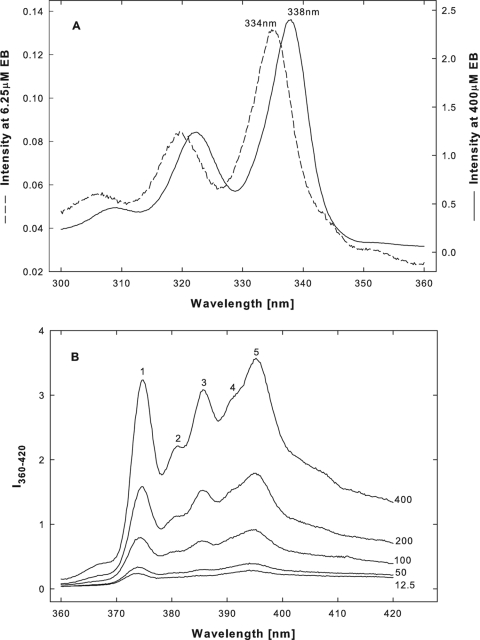

We examined EB peptides for their ability to self associate over a critical concentration range by recording spectral changes due to the sequestration of pyrene in the hydrophobic microenvironment of peptide aggregates (2, 20, 44). The effects of EB and EBX on pyrene excitation and emission fluorescence spectra were first compared in hypertonic buffer. The three most prominent spectral changes are shown in Fig. 9B to D, and typical examples of EB-induced changes in excitation and emission fluorescence spectra are shown in Fig. 10A and B, respectively.

FIG. 10.

EB induced changes in pyrene excitation and emission fluorescence spectra. Examples of excitation (A) and emission fluorescence (B) spectra, from which the data in Fig. 9B to D were obtained, are shown. All spectra were taken in clear hypertonic solutions at 15°C. In panel A, the red shift of the principal peak from 334 to 338 nm is indicated. In panel B, the five major emission peaks are labeled (1 to 5); numbers to the right of each spectrum are EB concentrations in μM.

At precipitating concentrations between 40 and 400 μM, EB induced a red shift in the pyrene excitation spectrum (Fig. 9B, ▴), characteristic of aggregate formation in typical micellar systems (44). The red shift was measured as the ratio of intensities at wavelengths of 338 and 334 nm and was accompanied by a sharp increase in the total pyrene emission fluorescence measured at wavelengths of 360 to 420 nm (Fig. 9C, ▴). EB-induced changes in the fine structure of pyrene emission fluorescence spectra were defined as the ratio of the maximal intensity at peak 3 to the minimal intensity between peaks 1 and 2 (I3/I1/2 ratio), which is a convenient measure of the “sharpening” of spectral profiles (20) (see Fig. 10 for peak identification). The change in the I3/I1/2 ratio closely matched the change in the I338/I334 ratio (Fig. 9D, ▴, versus 9B, ▴). In parallel experiments, we confirmed that each of the three spectral changes also accompanied SDS micellization at a concentration of 8 to 10 mM (20) (data not shown).

Apparently, the highly cooperative EB-mediated aggregation of β-galactosidase was closely associated with a set of coordinate spectral changes indicative of peptide self association. Correspondingly, EBX, which did not precipitate proteins at concentrations as high as 800 μM (see above), initiated spectral changes as did EB, only at 10- to 30-fold-higher concentrations. No spectral changes were detected below precipitating EB concentrations, suggesting that the enzymatic activity of β-galactosidase was inhibited exclusively by monomeric peptide. Since BSA aggregation by EB peptides was completely suppressed at elevated NaCl concentrations (Fig. 4B), it was necessary to examine β-galactosidase aggregation and peptide self association also under different ionic conditions.

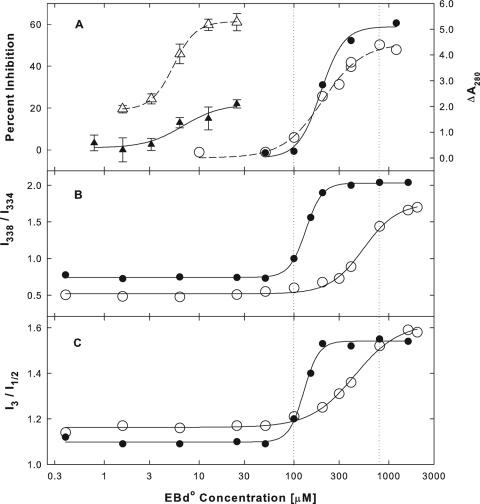

Effects of salt on β-galactosidase aggregation and peptide self association.

For these studies, we used the EBd° peptide, which blocked HSV-1 infection as efficiently as the EBd− or EB peptide (data not shown). We initially confirmed our earlier observation (Fig. 8C) that the inhibition of β-galactosidase activity by EB peptides under hypotonic conditions was alleviated at increased NaCl concentrations (Fig. 11A, ▵ versus ▴). In contrast, hypertonic conditions did not interfere with EBd°-mediated β-galactosidase aggregation (Fig. 11A, ○ versus •) even though EBd°-mediated BSA aggregation was completely suppressed (data not shown). At concentrations between 100 and 800 μM, EBd° induced essentially the same changes in pyrene excitation and emission fluorescence spectra as EB. The spectral changes are shown in Fig. 11B and C, respectively.

FIG. 11.

Effects of ionic conditions on EBd°-mediated inactivation and aggregation of β-galactosidase and on peptide self-association. Inhibition of the enzymatic activity of E. coli β-galactosidase (A) (▵ and ▴; 0.04 μg/ml) by EBd° was measured as described in the legend to Fig. 8A. Aggregation of β-galactosidase (A) (○ and •; 300 μg/ml) by EBd° was measured as described in the legend to Fig. 9A. Self association of EBd° was measured as a red shift in pyrene excitation spectra (B) (see Fig. 9B) or as a change in the fine structure of pyrene emission fluorescence spectra (C) (see Fig. 9D). Measurements were made either in hypotonic buffer (open symbols) with 2 mM MgCl2 in 10 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 7.4) or in hypertonic buffer (filled symbols) with an additional 0.3 M NaCl. All spectra were obtained from clear solutions either at 15 (○) or 25°C (•).

In hypertonic buffer, spectral changes occurred at lower EBd° concentrations than in hypotonic medium (Fig. 11B and C, • versus ○), indicating that peptide self association was enhanced at the higher salt concentration. This is consistent with the finding that salts usually enhance micellization of ionic surfactants (29). Furthermore, in hypertonic buffer, spectral changes occurred coincidentally with β-galactosidase aggregation, whereas under hypotonic conditions, aggregation was initiated in the absence of spectral changes. This suggests that β-galactosidase aggregation under hypertonic conditions was dependent on peptide self association whereas under hypotonic conditions it was initiated by monomeric peptide before self association could take effect.

Temperature effects.

All spectral changes reported here were recorded in clear hyper- or hypotonic buffers at pH 7.4 and 15°C. At and above critical peptide concentrations, all of these solutions gradually became cloudy and eventually formed precipitates at room temperature (∼23°C). The only exception was the EBd° peptide in hypertonic buffer solutions, which remained clear indefinitely. Any precipitates formed at room temperature were readily dissolved again by cooling the solutions to 15°C or lower temperatures. The transient peptide precipitation had no effect on pyrene fluorescence spectra. Peptide self association was therefore also defined by a lower critical solution temperature (LCST) (16), ranging from 15 to 23°C, except for EBd° in hypertonic buffer (>25°C). None of the EB peptides precipitated in unbuffered aqueous solutions even at concentrations as high as 30 to 40 mM.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that the antiviral effects of EB peptides are not restricted to direct interactions with virions but can also protect cells from infection. Host cells gain such protection at low peptide concentrations (<20 μM) in a serum-dependent manner, requiring BSA as a cofactor. At concentrations above 40 to 100 μM, interactions of EB with BSA and other proteins cause protein aggregation. The ability to precipitate proteins appears to be related to EB peptides acting as cationic surfactants that self associate in a process resembling micelle formation. To evaluate the pharmacological potential of EB, it was necessary to explore both its prophylactic effects and its detergent-like interactions with proteins in some detail.

Pretreatment of cells with EB peptides in the presence of serum or BSA had essentially the same antiviral effects as pretreatment with TAT-C peptides (7). Representatives of two other types of cationic antiviral peptides (HOM and KLA peptides) (5) also protected Vero cells from HSV-1 infection (our unpublished results). However, pretreatment of the same cells with the same peptide did not necessarily provide the same protection against different viruses, suggesting that the cell surface is not merely a passive peptide carrier. For example, pretreatment of MDCK cells with EB in the presence of 1% BSA severely inhibited subsequent HSV-1 infection in the absence of peptide (EC50 = 1.9 μM). In contrast, infection with influenza virus (A/HongKong/483/97) was completely unaffected under the same conditions (J. C. Jones and H. Bultmann, unpublished results) despite the fact that EB is a virucidal inhibitor of influenza virus (19). Cellular effects of EB also seem to play little or no role in blocking infections with vaccinia virus (1). Given the multiple and broad-spectrum antiviral activities of EB peptides, we expect that they will prove useful, for example, as topical agents blocking HSV transmission or in inhalers for blocking respiratory infections, as we showed previously for influenza virus in a mouse model (19).

Presumably, most of the EB peptide is tightly bound to cell surface heparan sulfates, as indicated in binding studies with biotinylated peptide. Thus, bEB bound to live Vero cells or to immobilized heparin at 4°C and could not be dislodged by rinsing the cell cultures with 0.5 M NaCl or the heparin-coated wells with 2 M NaCl, even though bound biotinylated TAT peptide was completely removed (our unpublished results). Recent studies (21) have shown that melittin, the major antimicrobial and hemolytic peptide in honey bee venom (13), also binds to sulfated cell surface sugars, whereas two other cationic AMPs (magainin 2 and nisin Z) do not. Melittin consists of 26 residues and resembles EB in that it includes a cluster of lysines and arginines (KRKR) next to a long stretch of hydrophobic amino acids. Binding of melittin to glycosaminoglycans seems to contribute to the cytotoxic activity of the peptide, and this may also be true for EB. However, it seems unlikely that binding of EB to cell surface heparan sulfates was critical for antiviral activity, since virucidal treatments blocked infection primarily at a postadsorption step and actually enhanced virus attachment to cells (6). Furthermore, since cell pretreatments, like virucidal treatments, affected extracellular virus exclusively, it seems clear that infection was blocked at an early stage, presumably at the entry step.

EB peptides at high concentrations appear to be general aggregation agents for proteins, though ionic conditions may differentially modify the responses of different proteins (BSA versus β-galactosidase). Different ionic conditions (20 to 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2+) also modified the inhibition of β-galactosidase at low peptide concentrations, presumably by interfering with peptide-protein interactions without directly affecting the enzymatic activity (17). The effects of ionic conditions suggest that the charged head group of EB peptides (RRKK) is functionally not irrelevant. The greatly diminished potency of the EBX peptide, however, indicates that functional properties of EB peptides depend primarily on the sequence of hydrophobic residues. None of the biological or biochemical properties of EB peptides seem to depend on chirality or on any stereospecific peptide interactions.

Interactions of EB peptides with β-galactosidase provide a useful model for understanding interactions of these peptides with virions. HSV-1 virions are irreversibly inactivated at EB concentrations between 20 and 200 μM, with EC50s ranging from 44 to 89 μM depending on the temperature (37 and 4°C, respectively) (5, 6). The virucidal peptide concentrations widely overlap with peptide concentrations precipitating β-galactosidase (40 to 400 μM). This suggests that the nonspecific irreversible denaturation of one or more envelope glycoproteins might account for the virucidal effects of EB peptides. EB is also known to cause virus aggregation. Virus aggregates have been visualized by electron microscopy, and filtration experiments have shown that such aggregates are formed at peptide concentrations as low as 5 μM (6). Such low peptide concentrations do not cause protein aggregation but still inhibit the enzymatic activity of β-galactosidase. Presumably, they might induce minor conformational changes in envelope glycoproteins that could account for virus aggregation and for enhanced cell surface binding of peptide-treated virions. The fact that β-galactosidase was inhibited at low concentrations of monomeric EB peptides further suggests that nonspecific detergent-like interactions of EB with proteins may also contribute to cellular protection from viral infection. This is entirely consistent with our finding that the requirement of BSA as an EB cofactor does not require BSA aggregation. Conventional detergents are well known to denature proteins well below the critical micelle concentration (see the introduction), and further physical studies are required to determine whether this is also true for EB peptides. Finally, cell viability also seems to be limited by the detergent-like properties of EB peptides, notably their self association, which was closely associated with cytotoxic effects.

Evidence for the formation of micelle-like structures during self association of EB peptides came primarily from spectroscopic studies, since excitation and emission fluorescence spectra exhibited several coordinate transitions typically associated with pyrene sequestration during micellization (2, 20, 44). Furthermore, in near-neutral buffers and at concentrations above 40 to 100 μM, EB precipitated above an LCST of 15 to 23°C in a manner readily reversible at temperatures of ≤15°C. Finally, as has also been shown for other amphiphiles (29), addition of NaCl facilitated self association of EB peptides.

In hypertonic buffer (0.3 M NaCl), EBd°-mediated β-galactosidase aggregation and EBd° self association seemed to occur coincidentally. We can dismiss the possibility that protein aggregation may be an artifact of peptide precipitation, because β-galactosidase was precipitated well below the LCST of EBd°. Furthermore, both protein aggregation and peptide self association were coordinately suppressed in the EBX peptide. It appears, therefore, that protein aggregation is directly linked to the formation of micelle-like peptide clusters. This does not imply that protein aggregation is driven by protein binding to external micelle-like structures formed in solution. Thus, BSA aggregation was prevented in the presence of 0.3 M NaCl despite the fact that self association of the peptide was enhanced. The possibility that monomeric peptide facilitated protein aggregation was suggested by the finding that the initial increase in β-galactosidase absorbance induced by EBd° in hypotonic buffer was not accompanied by any change in pyrene spectra. Both findings are consistent with the notion that protein aggregation by amphiphiles is due not to protein binding to micelles formed in solution but rather to micellization of amphiphiles initially bound to proteins as monomers. This has been confirmed for BSA interacting with SDS (36, 40) and for other systems (e.g., see reference 34). Direct binding studies will be required to decide whether this also applies to detergent-like interactions of EB peptides with proteins.

Changes in pyrene fluorescence spectra at critical concentrations of EB peptides or SDS were indistinguishable, with one notable exception. The I3/I1 ratio, reflecting relative intensities of peaks 3 and 1 in fluorescence spectra, remained invariant throughout the range of peptide concentrations tested, whereas micellization of SDS at a concentration of 8 to 10 mM was accompanied by a sharp increase in the I3/I1 ratio from 0.63 to 0.90 (our unpublished results) (20). This discrepancy remains unexplained, and further studies are required to address this anomaly. Other amphiphilic cationic peptides are known to aggregate spontaneously forming tetramers, as in the case of melittin (38, 39), or long filamentous structures, as in the case of magainin 2 (41). The formation of such aggregates is apparently unrelated to the self association of EB peptides described here.

It seems clear that at critical concentrations above 40 to 100 μM, the EB peptides act in a detergent-like manner. It is not known whether, in addition to proteins, they also affect membranes. Acting in a nonstereospecific detergent-like manner, EB peptides may evade antimicrobial resistance effectively regardless of whether they target proteins or membranes. From this perspective, one might anticipate that detergent-like interactions with proteins are not unique to EB peptides but may also be part of the repertoire of other cationic amphiphilic peptides.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants from the NIH to C.R.B. (P01-AI52049 and P30-EY016665), a Senior Scientist Award to C.R.B. from Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB), an unrestricted grant from RPB to the Department of Ophthalmology & Visual Sciences, and a grant from the NIH to G.S.K. (R01-AI043346-12).

Pyrene probe fluorescence spectra were obtained at the Analytical Instrumentation Center in the School of Pharmacy, University of Wisconsin—Madison. We thank Elizabeth Froelich for administrative assistance, Donna Peters for the gift of dimeric human fibronectin, and Gary Case for HPLC assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 July 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altmann, S. E., J. C. Jones, S. Schultz-Cherry, and C. R. Brandt. 2009. Inhibition of vaccinia virus entry by a broad spectrum antiviral peptide. Virology 388:248-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Astafieva, I., X. F. Zhong, and A. Eisenberg. 1993. Critical micellization phenomena in block polyelectrolyte solutions. Macromolecules 26:7339-7352. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bechinger, B., and K. Lohner. 2006. Detergent-like actions of linear amphipathic cationic antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1758:1529-1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brogden, K. A., J. M. Guthmiller, M. Salzet, and M. Zasloff. 2005. The nervous system and innate immunity: the neuropeptide connection. Nat. Immunol. 6:558-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bultmann, H., and C. R. Brandt. 2002. Peptides containing membrane-transiting motifs inhibit virus entry. J. Biol. Chem. 277:36018-36023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bultmann, H., J. S. Busse, and C. R. Brandt. 2001. Modified FGF4 signal peptide inhibits entry of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 75:2634-2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bultmann, H., J. Teuton, and C. R. Brandt. 2007. Addition of a C-terminal cysteine improves the anti-herpes simplex virus activity of a peptide containing the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 TAT protein transduction domain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1596-1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cruciani, R. A., J. L. Barker, S. R. Durell, G. Raghunathan, H. R. Guy, M. Zasloff, and E. F. Stanley. 1992. Magainin 2, a natural antibiotic from frog skin, forms ion channels in lipid bilayer membranes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 226:287-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.del Castillo, F. J., I. del Castillo, and F. Moreno. 2001. Construction and characterization of mutations at codon 751 of the Escherichia coli gyrB gene that confer resistance to the antimicrobial peptide microcin B17 and alter the activity of DNA gyrase. J. Bacteriol. 183:2137-2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dennis, M. S., M. Zhang, Y. G. Meng, M. Kadkhodayan, D. Kirchhofer, D. Combs, and L. A. Damico. 2002. Albumin binding as a general strategy for improving the pharmacokinetics of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 277:35035-35043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durr, M., and A. Peschel. 2002. Chemokines meet defensins: the merging concepts of chemoattractants and antimicrobial peptides in host defense. Infect. Immun. 70:6515-6517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein, D. J., and S. K. Weller. 1988. Herpes simplex virus type 1-induced ribonucleotide reductase activity is dispensable for virus growth and DNA synthesis: isolation and characterization of an ICP6 lacZ insertion mutant. J. Virol. 62:196-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Habermann, E. 1972. Bee and wasp venoms. Science 177:314-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hancock, R. E., and H. G. Sahl. 2006. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Biotechnol. 24:1551-1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helenius, A., and K. Simons. 1975. Solubilization of membranes by detergents. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 415:29-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heskins, M., and J. E. Guillet. 1968. Solution properties of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide). J. Macromol. Sci. A Chem. 2:1441-1455. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill, J. A., and R. E. Huber. 1971. Effects of various concentrations of Na+ and Mg 2+ on the activity of β-galactosidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 250:530-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imura, Y., N. Choda, and K. Matsuzaki. 2008. Magainin 2 in action: distinct modes of membrane permeabilization in living bacterial and mammalian cells. Biophys. J. 95:5757-5765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones, J. C., E. A. Turpin, H. Bultmann, C. R. Brandt, and S. Schultz-Cherry. 2006. Inhibition of influenza virus infection by a novel antiviral peptide that targets viral attachment to cells. J. Virol. 80:11960-11967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalyanasundaram, K., and J. K. Thomas. 1977. Environmental effects on vibronic band intensities in pyrene monomer fluorescence and their application in studies of micellar systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 99:2039-2044. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klocek, G., and J. Seelig. 2008. Melittin interaction with sulfated cell surface sugars. Biochemistry 47:2841-2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kragol, G., S. Lovas, G. Varadi, B. A. Condie, R. Hoffmann, and L. Otvos, Jr. 2001. The antibacterial peptide pyrrhocoricin inhibits the ATPase actions of DnaK and prevents chaperone-assisted protein folding. Biochemistry 40:3016-3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langel, U. (ed.). 2007. Handbook of cell-penetrating peptides, 2nd ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 24.Lee, H. S., C. B. Park, J. M. Kim, S. A. Jang, I. Y. Park, M. S. Kim, J. H. Cho, and S. C. Kim. 2008. Mechanism of anticancer activity of buforin IIb, a histone H2A-derived peptide. Cancer Lett. 271:47-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin, Y. Z., S. Y. Yao, R. A. Veach, T. R. Torgerson, and J. Hawiger. 1995. Inhibition of nuclear translocation of transcription factor NF-kappa B by a synthetic peptide containing a cell membrane-permeable motif and nuclear localization sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 270:14255-14258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowenthal, M. S., A. I. Mehta, K. Frogale, R. W. Bandle, R. P. Araujo, B. L. Hood, T. D. Veenstra, T. P. Conrads, P. Goldsmith, D. Fishman, E. F. Petricoin III, and L. A. Liotta. 2005. Analysis of albumin-associated peptides and proteins from ovarian cancer patients. Clin. Chem. 51:1933-1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makino, S., J. A. Reynolds, and C. Tanford. 1973. The binding of deoxycholate and Triton X-100 to proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 248:4926-4932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuzaki, K., O. Murase, N. Fujii, and K. Miyajima. 1995. Translocation of a channel-forming antimicrobial peptide, magainin 2, across lipid bilayers by forming a pore. Biochemistry 34:6521-6526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukerjee, P. 1967. The nature of the association equilibria and hydrophobic bonding in aqueous solutions of association colloids. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1:241-275. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nielsen, M. M., K. K. Andersen, P. Westh, and D. E. Otzen. 2007. Unfolding of beta-sheet proteins in SDS. Biophys. J. 92:3674-3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nozaki, Y., J. A. Reynolds, and C. Tanford. 1974. The interaction of a cationic detergent with bovine serum albumin and other proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 249:4452-4459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oren, Z., and Y. Shai. 1998. Mode of action of linear amphipathic alpha-helical antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers 47:451-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otzen, D. E. 2002. Protein unfolding in detergents: effect of micelle structure, ionic strength, pH, and temperature. Biophys. J. 83:2219-2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otzen, D. E., P. Sehgal, and P. Westh. 2009. Alpha-lactalbumin is unfolded by all classes of surfactants but by different mechanisms. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 329:273-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peschel, A., and H. G. Sahl. 2006. The co-evolution of host cationic antimicrobial peptides and microbial resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:529-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reynolds, J. A., and C. Tanford. 1970. Binding of dodecyl sulfate to proteins at high binding ratios. Possible implications for the state of proteins in biological membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 66:1002-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Satoh, A., K. Kojima, T. Koyama, H. Ogawa, and I. Matsumoto. 1998. Immobilization of saccharides and peptides on 96-well microtiter plates coated with methyl vinyl ether-maleic anhydride copolymer. Anal. Biochem. 260:96-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Talbot, J. C., J. Dufourcq, J. de Bony, J. F. Faucon, and C. Lussan. 1979. Conformational change and self association of monomeric melittin. FEBS Lett. 102:191-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terwilliger, T. C., L. Weissman, and D. Eisenberg. 1982. The structure of melittin in the form I crystals and its implication for melittin's lytic and surface activities. Biophys. J. 37:353-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turro, N. J., X.-G. Lei, K. P. Ananthapadmanabhan, and M. Aronson. 1995. Spectroscopic probe analysis of protein-surfactant interactions: the BSA/SDS system. Langmuir 11:2525-2533. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Urrutia, R., R. A. Cruciani, J. L. Barker, and B. Kachar. 1989. Spontaneous polymerization of the antibiotic peptide magainin 2. FEBS Lett. 247:17-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, G., X. Li, and Z. Wang. 2009. APD2: the updated antimicrobial peptide database and its application in peptide design. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D933-D937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiedemann, I., E. Breukink, C. van Kraaij, O. P. Kuipers, G. Bierbaum, B. de Kruijff, and H. G. Sahl. 2001. Specific binding of nisin to the peptidoglycan precursor lipid II combines pore formation and inhibition of cell wall biosynthesis for potent antibiotic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 276:1772-1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilhelm, M., C. L. Zhao, Y. Wang, R. Xu, M. A. Winnik, J. L. Mura, G. Riess, and M. D. Croucher. 1991. Poly(styrene-ethylene oxide) block copolymer micelle formation in water: a fluorescence probe study. Macromolecules 24:1033-1040. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang, L., T. M. Weiss, R. I. Lehrer, and H. W. Huang. 2000. Crystallization of antimicrobial pores in membranes: magainin and protegrin. Biophys. J. 79:2002-2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yeaman, M. R., and N. Y. Yount. 2003. Mechanisms of antimicrobial peptide action and resistance. Pharmacol. Rev. 55:27-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zasloff, M. 2002. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 415:389-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]