Abstract

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is one of the most important multidrug-resistant pathogens around the world. MRSA is generated when methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) exogenously acquires a methicillin resistance gene, mecA, carried by a mobile genetic element, staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec), which is speculated to be transmissible across staphylococcal species. However, the origin/reservoir of the mecA gene has remained unclear. Finding the origin/reservoir of the mecA gene is important for understanding the evolution of MRSA. Moreover, it may contribute to more effective control measures for MRSA. Here we report on one of the animal-related Staphylococcus species, S. fleurettii, as the highly probable origin of the mecA gene. The mecA gene of S. fleurettii was found on the chromosome linked with the essential genes for the growth of staphylococci and was not associated with SCCmec. The mecA locus of the S. fleurettii chromosome has a sequence practically identical to that of the mecA-containing region (∼12 kbp long) of SCCmec. Furthermore, by analyzing the corresponding gene loci (over 20 kbp in size) of S. sciuri and S. vitulinus, which evolved from a common ancestor with that of S. fleurettii, the speciation-related mecA gene homologues were identified, indicating that mecA of S. fleurettii descended from its ancestor and was not recently acquired. It is speculated that SCCmec came into form by adopting the S. fleurettii mecA gene and its surrounding chromosomal region. Our finding suggests that SCCmec was generated in Staphylococcus cells living in animals by acquiring the intrinsic mecA region of S. fleurettii, which is a commensal bacterium of animals.

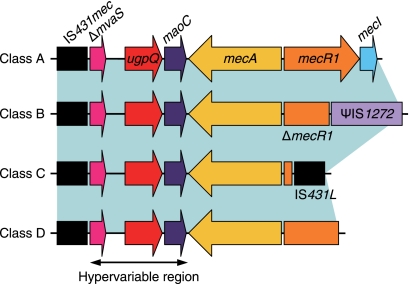

The first methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolate was reported in England in 1961, soon after the introduction of methicillin (10). Since then, it has become an important pathogen in both health care settings and communities around the world (27). MRSA is generated when methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) exogenously acquires a staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) (9). SCCmec has been identified not only in S. aureus but also in other coagulase-positive and coagulase-negative staphylococci (8). SCCmec is speculated to be transmissible among staphylococcal species as a mobile element; however, its origin/reservoir has not been clarified yet (7). Finding the origin/reservoir of the mecA gene is important for understanding the evolution of MRSA. Moreover, it may contribute to more effective control measures for MRSA. There are various types and subtypes in SCCmec, but they are made up of the following two essential components: (i) the mec gene complex, containing the mecA gene encoding the penicillin-binding protein 2′ (PBP2′) with reduced affinity to beta-lactam antibiotics, and (ii) the ccr gene complex, encoding site-specific recombinase(s) for the movement of the element. By the action of ccr gene-encoded recombinases, SCCmec is excised from the chromosome and site-specifically integrated at the 3′ end of orfX (11), an open reading frame (ORF) of unknown function, which is located near the replication origin (oriC) on the chromosome (13). A large number of SCCmec elements have been sequenced and classified according to the combination of types of mec and ccr gene complexes (8). Although nucleotide diversity of ccr genes identified in various Staphylococcus species has been reported, mecA genes contained in SCCmec are almost identical regardless of the Staphylococcus species carrying them (8). mec gene complexes are classified into 4 classes (classes A, B, C, and D) by the presence or absence of certain insertion sequences (ISs) in the mecR1 gene, but all mec gene complexes contained IS431mec (also called IS431R) downstream of the mecA gene (Fig. 1) (8, 12). The class A mec gene complex is regarded as the prototypic structure, having the gene order IS431mec-mecA-mecR1-mecI. Class B, C, and D mec gene complexes are considered to be derived from the class A mec gene complex (8, 12). The region between the mecA gene and IS431mec is called a hypervariable region (HVR) (19), which can be used for genotyping of MRSA strains (21). The HVR contains a truncated mvaS gene encoding the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) synthase, a varied number of direct repeat units (DRUs) that is responsible for the length polymorphism of the mec gene complex (19), an intact ugpQ gene encoding glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase, and an intact maoC gene encoding the acyl dehydratase MaoC (Fig. 1). Some strains, however, lack some of the above-mentioned constituents of the HVR (16, 24).

FIG. 1.

Basic structure of the representative mec gene complex. The class A mec gene complex is composed of intact mecR1 and mecI, encoding the signal transducer and repressor for the mecA gene, respectively, upstream of the mecA gene without integration of an IS element. The class B and C mec gene complexes have ψIS1272 and IS431L integrated in mecR1, respectively, which results in the partial deletion of mecR1 and complete deletion of the mecI genes. Class D has no IS element, but a part of mecR1 and complete mecI genes are deleted. All mec gene complexes contained IS431mec (also called IS431R) downstream of the mecA gene.

In staphylococci, previously, two mecA gene homologues with 80% and 91% nucleotide identities have been found in Staphylococcus sciuri and Staphylococcus vitulinus species, respectively (5, 22). The mecA gene homologue of S. sciuri has been considered to have a ubiquitous presence among its species and to be the evolutionary precursor of the mecA gene (5, 32). However, the mecA gene homologues found in their chromosomes were not the constituents of the mec gene complex or SCCmec. We speculated that the origin/reservoir of the mecA gene would be found in a staphylococcal species closely associated with S. sciuri and S. vitulinus. These species belong to the S. sciuri species group among the genus Staphylococcus. The group is composed of the following four species, which are resistant to novobiocin and catalase production and coagulase nonproduction: S. sciuri, S. vitulinus, Staphylococcus lentus, and Staphylococcus fleurettii (20, 25, 29, 30). They are usually isolated from a variety of animals and food products of animal origin and not frequently isolated from humans (20, 23, 25, 29, 30).

We isolated staphylococcal strains of the S. sciuri species group from an animal source, tested for the presence of the mecA gene and its homologues, and determined the nucleotide sequences of the chromosome regions around the mecA gene and its homologues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

S. sciuri species group strains used in this study are shown in Table 1. We identified bacterial strains by determination of the hsp60 and/or sodA sequences, as described in previous reports (14, 17). We also used Staphylococcus kloosii strain ATCC 43959T and Staphylococcus xylosus strain ATCC 29971T to determine the mvaS gene sequences.

TABLE 1.

Characterization of the S. sciuri species group strains used in this study

| Species | Strain | Source | mecA homologue | MIC (μg/ml) |

Typea | No. of DRUsb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxacillin | Ampicillin | Ceftizoxime | Ceftriaxone | Cefoxitin | ||||||

| S. fleurettii | SFMP01 (CCUG 43834T) | Cheese (made of goat milk) | mecASf | 64 | 1 | 32 | 16 | 2 | A | 5 |

| SFMP02 | Chicken meat | mecASf | 8 | 1 | 32 | 16 | 1 | A | 5 | |

| SFMP03 | Chicken meat | mecASf | 128 | 1 | 128 | 64 | 8 | A | 5 | |

| SFMP04 | Chicken meat | mecASf | 128 | 1 | 64 | 64 | 4 | A | 5 | |

| SFMP05 | Chicken meat | mecASf | 32 | 0.25 | 4 | 8 | 1 | A | 10 | |

| SFMP06 | Cock | mecASf | 64 | 1 | 32 | 32 | 2 | B | 0 | |

| SFMP07 | Cat | mecASf | 8 | 0.25 | 4 | 8 | 1 | B | 0 | |

| SFMP08 | Chicken meat | mecASf | 64 | 1 | 32 | 16 | 2 | C | 1 | |

| SFMN01 | Horse | NDc | 0.5 | 0.125 | 2 | 4 | 2 | D | 0 | |

| SFMN02 | Horse | ND | 0.5 | 0.125 | 2 | 4 | 2 | E | 0 | |

| S. sciuri subsp. carnaticus | ATCC 700058T | Eastern gray squirrel | mecASs | 1 | 0.125 | 2 | 8 | 2 | ||

| S. sciuri subsp. sciuri | ATCC 29062T | Veal leg, sliced | mecASs | 0.5 | 0.125 | 2 | 8 | 2 | ||

| S. sciuri subsp. rodentium | ATCC 700061T | Norway rat | mecASs | 0.5 | 0.125 | 2 | 8 | 2 | ||

| S. vitulinus | SVMP01 | Horse | mecASv | 0.5 | <0.063 | 0.5 | 4 | 2 | ||

| SVMP02 | Horse | mecASv | 0.5 | <0.063 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | |||

| SVMP03 | Horse | mecASv | 0.5 | <0.063 | 0.5 | 4 | 2 | |||

| SVMP04 | Horse | mecASv | 0.5 | <0.063 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | |||

| SVMP05 | Horse | mecASv | 0.5 | <0.063 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |||

| SVMP06 | Horse | mecASv | 0.5 | <0.063 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | |||

| SVMN01 (ATCC 51145T) | Ground lamb | ND | 0.5 | 0.125 | 4 | 8 | 2 | |||

| SVMN02 | Horse | ND | 0.5 | <0.063 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |||

| SVMN03 | Horse | ND | 0.5 | <0.063 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | |||

| SVMN04 | Horse | ND | 0.5 | <0.063 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | |||

| SVMN05 | Horse | ND | 0.25 | <0.063 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | |||

| SVMN06 | Horse | ND | 0.5 | <0.063 | 0.5 | 4 | 2 | |||

| SVMN07 | Horse | ND | 0.5 | <0.063 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 | |||

| SVMN08 | Horse | ND | 0.5 | <0.063 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |||

| SVMN09 | Horse | ND | 0.5 | <0.063 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | |||

| SVMN10 | Horse | ND | 0.5 | <0.063 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | |||

| SVMN11 | Horse | ND | 0.5 | 0.125 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |||

| SVMN12 | Horse | ND | 0.5 | <0.063 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | |||

| SVMN13 | Horse | ND | 0.5 | <0.063 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | |||

| SVMN14 | Horse | ND | 0.5 | <0.063 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | |||

| S. lentus | ATCC 29070T | Goat udder | ND | 0.5 | <0.063 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||

Genomic structure types of S. fleurettii.

DRUs separated by an IS element were counted as one DRU.

ND, not detected.

DNA manipulations.

Preparation of DNA, inverse PCR, nested PCR, nucleotide sequence determination, and alignment were based on previously published protocols (9, 33). Detection of mecA genes and their homologues was carried out by degenerate PCR, using synthetic primers MECA1 and MECA2 with the nucleotide sequences 5′-CCWMAAACWGGHGAAYTVTTAGC-3′ and 5′-CCYTGKCCRTAWCCTGARTCWGC-3′, respectively. These primers were designed by multiple alignments of the nucleotide sequences of the mecA genes of SCCmec, the mecA gene homologues of S. sciuri and S. vitulinus, and the mecA gene of Macrococcus caseolyticus (mecAMc), obtained from the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank/). The PCR mixture contained 100 ng DNA extract, 10 pmol of each primer, 1× PCR buffer, 0.2 mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), and 2 U Ex Taq (Takara Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan). The PCR thermal cycling conditions used were 1 cycle at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 30s, 50°C for 30s, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final cycle at 72°C for 2 min. The sequencing analyses of the PCR products were preformed.

The nucleotide sequences of the mvaS genes of S. aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus capitis, Staphylococcus warneri, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Staphylococcus haemolyticus, and Staphylococcus hominis were obtained from the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank/). A set of primers, MSC1 and MSC2, with nucleotide sequences 5′-GGTIATHGTDGCAACWGARTCWG-3′ and 5′-CCCATTTTDGTRAAWGGWACRTGG-3′, respectively, were designed by multiple alignment of nucleotide sequences of these mvaS genes. By using the primers, we performed degenerate PCR to amplify the mvaS genes of S. xylosus, S. kloosi, and S. lentus. The PCR mixture contained 100 ng DNA extract, 10 pmol of each primer, 1× PCR buffer (Mg2+ free), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, and 2 U Ex Taq (Takara Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan). The PCR thermal cycling conditions used were 1 cycle at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 30s, 37°C for 30s, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final cycle at 72°C for 2 min. The sequencing analyses of the PCR products were preformed before the inverse PCR in order to determine the complete sequences of the mvaS genes.

Computer analysis.

ORFs were extracted with genome analysis-oriented software In Silico Molecular Cloning version 1.5 (In Silico Biology, Yokohama, Japan). Homology searches were performed using the Internet-available BLAST program from the National Center for Biotechnology Information, United States of America (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Phylogenetic analysis of mvaS, 16S rRNA, and mecA genes.

Phylogenetic analysis of mvaS genes of staphylococci was performed, with the mvaS gene nucleotide sequence of Listeria monocytogenes, obtained from GenBank database, as an outgroup. The nucleotide sequences of 16S rRNA of S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. capitis, S. warneri, S. saprophyticus, S. haemolyticus, S. hominis, S. sciuri, S. vitulinus, S. lentus, S. fleurettii, S. kloosii, S. xylosus, Staphylococcus carnosus, and L. monocytogenes (outgroup) were also obtained from the GenBank database. Phylogenetic analysis of mecA genes and its homologues was performed by using the mecAMc gene as an outgroup. The phylogenetic tree was generated by the CLUSTALW program using the neighbor-joining method (http://clustalw.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/top-j.html). The tree was visualized with TreeView software, Glasgow, United Kingdom (http://taxonomy.zoology.gla.ac.uk/rod/treeview.html).

Detection of xyl genes and xylose fermentation testing for S. sciuri.

Detection of the xylA-xylB gene of S. sciuri was carried out by PCR using primers XAS-F, 5′-GTGTTGCATACTGGCATAC-3′, and XBS-R, 5′-GCACCAATTTTAGACTGGG-3′, which amplify an anticipated 2,190-bp fragment. PCR was based on previously published protocols (12). Xylose fermentation tests were performed using purple agar base (Difco, Detroit, MI) with or without d-xylose at a 1% concentration. A colony was inoculated in the stab with an inoculating needle and incubated at 37°C for 48 h.

Detection and sequencing analyses of the regions between the mvaS and xylR genes and the xylR and xylE genes of S. vitulinus.

Detection of the region between the mvaS and xylR genes of S. vitulinus was performed by PCR using primers MVAV-1, 5′-CCAGAGAACACTTTGTATG-3′, and XYRV-1, 5′-GCATACCCCATAAGTCATTTTG-3′. Detection of the region between the xylR and xylE genes of S. vitulinus was performed by PCR using primers XYRV-2, 5′-GAAGCTATTAAGAACGAGTTC-3′, and XYEV-1, 5′-CCTACTCCAATACCACCG-3′. PCR and sequencing analyses were based on previously published protocols (12).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

MICs were determined by the agar dilution method using Mueller-Hinton agar (Difco, Detroit, MI), as recommended by the CLSI guidelines (3). The MIC breakpoints for resistance used were those recommended in the CLSI guidelines (4). The antibiotics tested were as follows: oxacillin, cefoxitin, and ceftriaxone (Sigma Chemical Co., Ltd., St. Louis, Mo); ampicillin (Pfizer, Inc.); and ceftizoxime (Fujisawa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Detection of the mecA genes and its homologues in the S. sciuri species group.

All 3 strains of S. sciuri, 6 of 20 strains of S. vitulinus, and 8 of 10 strains of S. fleurettii were found to be mecA positive by PCR analysis using the degenerate primers for amplifying the mecA genes and its homologues (Table 1). Sequencing analysis of the PCR products (512 bp) revealed that the nucleotide identities of the mecA genes detected in S. sciuri, S. vitulinus, and S. fleurettii strains shared with the mecA gene of MRSA strain N315 were 85 to 86%, 94%, and 99 to 100%, respectively. The PCR did not detect the mecA genes or mecA gene homologues in 10 independent S. lentus strains (data not shown).

Genomic structure analysis of the mecA gene region of S. fleurettii.

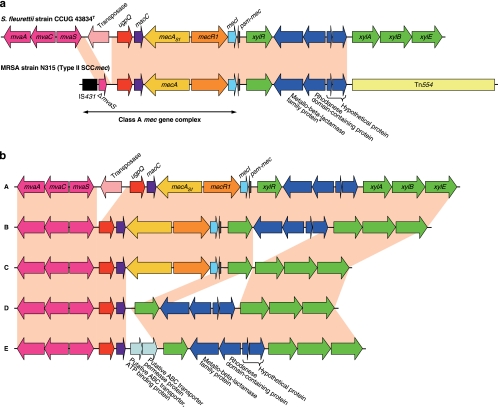

We performed genome analysis around the mecA gene by using inverse PCR-based sequencing analysis. Surprisingly, we found that S. fleurettii had an almost identical structure to that of the class A mec gene complex in SCCmec with an intact mvaS, which is not truncated by IS431mec found in MRSA strain N315 (Fig. 2 a). Moreover, the intact mvaS gene was followed by the mvaAC genes, constituting the mevalonate pathway (Fig. 2a) (31). Between the mvaS and mecA genes on the chromosome of S. fleurettii, the ugpQ and maoC genes, similar to those downstream of the mecA gene in SCCmec, were present. Upstream of mecA-R-I in S. fleurettii, genes encoding a phenol-soluble modulin mec (psm-mec) (18), xylose repressor (xylR), metallo-beta-lactamase family protein, rhodanase domain-containing protein, and two hypothetical proteins were present. This is also consistent with the corresponding region of the SCCmec of MRSA strain N315. In regard to the genetic organization following it, however, there were differences between S. fleurettii and the N315 SCCmec (Fig. 2a). In the S. fleurettii chromosome, xylABE encoding xylose isomerase, xylulokinase, and the xylose transporter, respectively, were identified, rather than Tn554 (encoding macrolide and streptomycin resistance) found in the N315 SCCmec, indicating that the xylR gene constituted an xyl operon with xylABE (26). Conversely, it became clear that the xylR gene present upstream of the class A mec gene complex was originally a part of the xyl operon. The mecA gene of S. fleurettii present at this gene locus is designated mecASf. This locus (Fig. 2a, pink) shared 99% nucleotide identity with the corresponding locus of type II SCCmec carried by MRSA strain N315. This correlation is found not only in MRSA strain N315 but also in strains carrying SCCmec type II, III, and VIII containing the class A mec gene complex. Such strains have been disseminated around the world. In reference to the GenBank database, this correlation is found in, for example, SCCmec type II of MRSA strains N315 from Japan, MRSA252 from United Kingdom, and 04-02981 from Germany and methicillin-resistant S. epidermidis strain RP62A from the United States; SCCmec type III of MRSA strains TW20 from United Kingdom, 85/2082 from New Zealand, and BK16704 from Romania and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius strains KM241 and KM1381 from Switzerland; and SCCmec type VIII of MRSA strain C10682 from Canada. In SCCmec type III, ψTn554 (encoding cadmium resistance) is present, rather than Tn554 found in SCCmec type II and VIII (8).

FIG. 2.

Genomic organization of the mecASf gene locus of S. fleurettii. (a) Comparison to the locus-containing type II SCCmec of MRSA strain N315. The mecASf-positive S. fleurettii possessed a stretch of chromosome sequence that was practically identical with that of MRSA SCCmec, spanning the class A mec gene complex and adjacent chromosomal region containing psm-mec, xylR, the genes encoding the metallo-beta-lactamase family protein, the rhodanase domain-containing protein, and other hypothetical proteins. The mvaS gene of S. fleurettii existed in intact form without insertion of IS431. Moreover, the xyl operon was identified on the S. fleurettii chromosome from which xylR of SCCmec must have originated. The entire corresponding regions of the two chromosomes are colored in pink. Arrows indicate the genes and their directions of transcription. Truncated mvaS is shown by ΔmvaS. *, The gene encoding the metallo-beta-lactamase family protein of MRSA strain N315 was a pseudogene with a nonsense mutation (ochre) incorporated next to codon 312. (b) Structural diversity observed in the mecASf gene loci of S. fleurettii strains. Five types (A, B, C, D, and E) were identified. The regions with practically identical nucleotide sequences across the mva and xyl genes are colored in pink. Arrows indicate the genes and their directions of transcription.

Sequencing analysis of the chromosomes of S. fleurettii strains revealed five structural diversities (Fig. 2b). Type A (5/10 strains, including strain CCUG 43834T) had an IS element between the mvaS and ugpQ genes (42% amino acid identity and 62% amino acid similarity to IS256). The IS was integrated into one of the DRUs. Type B (2/10 strains) had no IS element between the mvaS and ugpQ genes. In type C (1/10 strains), the xyl operon was present in its original form, xylRABE, without the insertions between xylR and xylA. One of the two mecASf-negative strains (type D) lacked mecR1, mecI, and psm-mec, and thus, the maoC and xylR genes were present side-by-side. The other mecASf-negative strain (type E) possessed genes encoding a putative ABC transporter ATP-binding protein and an ABC transporter permease protein (57% and 62% amino acid similarity to SERP0984 and SERP0983 of S. epidermidis strain RP62A, respectively) between the maoC and xylR genes. In eight mecASf-positive S. fleurettii strains, the regions between the mvaS and mecA genes, which corresponded to the HVR of the mec gene complex, showed the length polymorphism according to the varied number of DRUs (Table 1) and integration of the IS element.

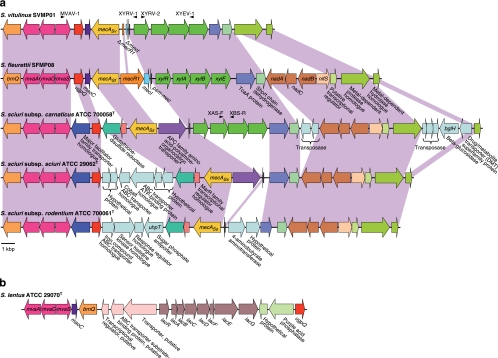

Genomic structure of the mecA gene homologue regions of S. sciuri and S. vitulinus in comparison with that of S. fleurettii.

We performed genome analysis around the mecA gene homologues of S. sciuri and S. vitulinus by using inverse PCR-based sequencing analysis. Compared with the genomic structure of S. fleurettii, similar genomic structure was found in the chromosomal region extending over 20 kbp in size around each mecA gene homologue (Fig. 3 a). The mecA gene homologues of S. sciuri and S. vitulinus present at the corresponding loci are designated mecASs and mecASv, respectively. Downstream of mecASf, mecASv and mecASs, the ugpQ, mvaACS, and brnQ genes encoding a branched chain amino acid ABC transporter were identified in all the three species. A mecASv-positive S. vitulinus strain possessed truncated remnants of the mecR1 and mecI genes upstream of mecASv. We confirmed that all 6 mecASv-positive S. vitulinus strains possessed practically identical mecASv genes and truncated mecR1 and mecI genes by conducting PCR testing followed by nucleotide sequencing, whereas mecASv-negative S. vitulinus strains were negative for these genes. Thus, in their chromosomes, maoC and psm-mec genes were found adjacent to each other. The adjacent xyl operon was well conserved in all 20 strains of S. vitulinus.

FIG. 3.

Genomic structure analysis of the S. sciuri species group. (a) The mecA gene homologue-containing chromosomal regions of S. vitulinus, S. sciuri subsp. carnaticus, S. sciuri subsp. sciuri, and S. sciuri subsp. rodentium compared to those of S. fleurettii. The corresponding regions among the species (and subspecies) are colored in light purple. Arrows indicate the genes and their directions of transcription. Noncorresponding genes found in these regions are shown with pale blue arrows. Truncated mecR1 and mecI are shown by ΔmecR1 and ΔmecI, respectively. The positions of primers (MVAV-1, XYRV-1, XYRV-2, XYEV-1, XAS-F, and XBS-R) are shown with arrowheads. The scale bar is not necessarily correlated with the noncoding region. *, The gene encoding the APC family amino acid-polyamine-organocation transporter of S. sciuri subsp. carnaticus strain ATCC 700058T was a pseudogene due to an early stop codon caused by a frameshift. (b) Genomic structure of the mvaSCA gene locus of S. lentus. Arrows indicate the genes and their directions of transcription.

S. sciuri did not carry mecR1 and mecI genes upstream of mecASs in any of its three subspecies. There were considerable differences in the genomic organization around mecASs genes among three subspecies (Fig. 3a). We identified the xyl operon in S. sciuri subsp. carnaticus strain ATCC 700058T but not in S. sciuri subsp. sciuri strain ATCC 29062T or S. sciuri subsp. rodentium ATCC 700061T on the corresponding locus. We confirmed the absence of the xyl operon in the latter two strains by PCR and xylose fermentation testing. Besides the xyl operon, differentiations of the three S. sciuri subspecies were accompanied by the insertion of some transporter genes. S. sciuri strains have been isolated from various sources, including animals, humans, and the environment (5). The ability of S. sciuri to survive in a wide range of environments may correlate with its intraspecies diversity such as the genomic structures observed in the mecASs chromosome locus.

In all the three tested species, genes encoding lipoprotein (TcaA protein), short-chain dehydrogenase, metal-dependent protease, and metal-dependent hydrolase were commonly identified downstream of mecASf, mecASv, and mecASs in identical gene order and orientation. Between genes encoding short-chain dehydrogenase and metal-dependent protease, nadA (encoding quinolinate synthetase), nadB (encoding l-aspartate oxidase), nadC (encoding nicotinate-nucleotide pyrophosphorylase), and nifS (encoding quinolinate synthetase) and a gene encoding a putative transcriptional regulator were commonly identified in S. fleurettii and S. sciuri but not in S. vitulinus. The genomic structure analysis of the chromosomal locus indicated that the mecA genes in this locus of the S. sciuri species group are descendants of the ancestral mecA gene carried by the common ancestor of S. fleurettii, S. vitulinus, and S. sciuri. The molecular differentiation of the archaic mecA gene into three alleles, mecASf, mecASv, and mecASs, must have occurred by evolutionary processes during speciation of the ancestor bacterium into each staphylococcal species.

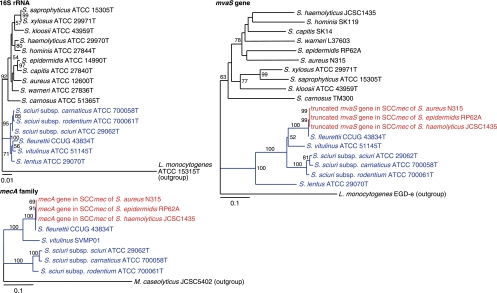

Phylogenetic analysis.

The mvaACS genes encode enzymes of the mevalonate pathway, which are involved in the biosynthesis of isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) (31). In staphylococci, the mevalonate pathway is composed of six genes, mvaC, mvaS, mvaA, mvaK1, mvaK2, and mvaD. These genes encode acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, HMG-CoA synthase, HMG-CoA reductase, mevalonate kinase, phosphomevalonate kinase, and mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase, respectively. All genes are essential for the growth of staphylococci (31). We performed the phylogenetic analysis of the mvaS genes of staphylococci. The topology of mvaS gene-derived tree was similar to that obtained by analyzing 16S rRNA genes (Fig. 4). The mvaS genes of the S. sciuri species group formed a separate cluster from the other staphylococci, which was analogous to that formed in the 16S rRNA-based tree. This confirmed the vertical transmission of mvaS gene from the ancestral bacterium. The tree also showed that mvaS of S. fleurettii was most closely related to the truncated mvaS gene present within the mec gene complex in SCCmec (Fig. 4). The nucleotide identity between them was 99.7%. Furthermore, the topology of the mecA gene and its homologue-derived tree was correlated with that of the S. sciuri species group, obtained by analyzing mvaS genes (Fig. 4). These results suggested that the archaic mvaS gene evolved with the archaic mecA gene, side-by-side with the chromosome locus of the ancestral bacterium. Therefore, our study indicated that S. fleurettii had inherited the mecA gene from its ancestor by the vertical transmission and had not recently acquired it.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA, mvaS, and mecA genes. Strain names are preceded by the names of the bacterial species. The branch length indicates the distance, which is expressed as the number of substitutions per 100 bases. Numbers at the branching points represent the percent occurrence in 1,000 random bootstrap replications of neighbor-joining analyses. Values of less than 50% are not shown. The sizes of mvaS genes varied from 1,167 to 1,179 bp, except for the truncated mvaS gene (369 bp) present in SCCmec. The genes identified in SCCmec and obtained from the S. sciuri species group are colored red and blue, respectively.

The mvaS gene of S. lentus, the fourth member of the S. sciuri species group, was somewhat distant from those of the other S. sciuri species group (Fig. 4). Genomic analysis of the mva gene locus of S. lentus also showed a genomic organization different from those of the other S. sciuri species group (Fig. 3b). By analyzing 10 independent strains, we identified the identical genomic structures upstream of the mva gene locus (data not shown). PCR did not detect the mecA gene homologue using whole cellular DNAs as templates. Therefore, the archaic mecA gene might have been carried by the common ancestor of S. sciuri, S. fleurettii, and S. vitulinus but not of S. lentus. Alternatively, S. lentus might have lost its mecA gene homologue at a certain stage of its evolutionary history.

Comparison of antibiotic resistance.

We determined beta-lactam MICs for the S. sciuri species group strains. mecASf-positive S. fleurettii strains had clearly higher MIC values for oxacillin, ceftizoxime, and ceftriaxone than mecASf-negative S. fleurettii strains. On the other hand, none of the three mecASs-carrying S. sciuri strains or mecASv-positive S. vitulinus strains exhibited resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics (Table 1). Expression of the mecA gene homologue of S. sciuri (mecASs) has been intensively studied (1). Although S. sciuri strains are uniformly susceptible to beta-lactam antibiotics, only its upregulated form in vitro or clinical isolates with a mutation or an IS element in the promoter region of mecASs showed beta-lactam resistance. In contrast, mecASf confers methicillin resistance, as it has a nucleotide sequence practically identical to that of the mecA gene of MRSA strain N315 (99.8% nucleotide identity compared to that of the mecASf gene of S. fleurettii strain CCUG 43834T). We speculated that the species S. fleurettii developed the mecASf gene in an environment where beta-lactam antibiotics frequently served as selective pressure during the speciation process.

Many studies on the function of the mecA gene have been done since the first discovery of MRSA in 1961. However, the origin/reservoir of the mecA gene has remained a mystery for half a century. Finally, we found in S. fleurettii the original chromosomal locus that must have served as the template for the mec gene complex of SCCmec. It is a commensal bacterium of animals. The formation of SCCmec seems to have occurred by a combination of the following two genetic components: the S. fleurettii-derived mec gene complex and an SCC element without the mecA gene. For the excision of the mec gene complex from the S. fleurettii chromosome, IS431mec might have been involved, because IS431 has been found as part of many composite transposons (2). It is controversial as to whether the new SCCmec is being frequently produced around the world even now or if the generation of SCCmec occurred in only a few events in the past before a limited number of SCCmec spread around the world and were modified into the extant genetic diversity of SCCmec. Recently, we reported a suggestive case for the formation of an SCCmec-like element from the two genetic components occurring in Macrococcus caseolyticus strains isolated from chicken meat (28). Macrococci are closely related to staphylococci and are also commensal bacteria of animals. The resultant SCCmec-like element was different from SCCmec of MRSA in terms of nucleotide sequence and genomic organization of the mec gene complex. However, this observation raises the possibility that the generation of the new SCCmec is also ongoing in staphylococci. In either case, S. fleurettii is considered to be the origin of mec gene complex. However, S. fleurettii itself may not form SCCmec on its chromosome, because it is intrinsically resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics due to the carriage of the mecASf gene on the chromosome. Hence, other methicillin-susceptible animal-borne Staphylococcus species coexistent with S. fleurettii would be more likely candidates for the formation of SCCmec. Such species might acquire the mecASf region from S. fleurettii to survive under conditions of antibiotic pressure, including exposure to fungi in the natural environment and medication in the livestock industry. Once SCCmec has been generated in or transferred into a broad-host-range Staphylococcus species, which could be isolated from various animals, as well as humans, the mecASf region carried by SCCmec might have spread beyond the host animal species. It is unknown whether SCCmec is generated in S. aureus, which is both a human-related and animal-related Staphylococcus species. It is our next agenda to find the bacterium in which SCCmec was generated as a mobile genetic element. One or more specific Staphylococcus species may play a role as a “reservoir” of the mobile genetic element SCCmec. Further studies are under way to investigate a reservoir of SCCmec.

We have been recently confronted with the rapid spread of community-acquired MRSA (27) and facilitated transmission of animal-derived MRSA to humans (6). It was previously considered that SCCmec is transmitted into S. aureus only rarely and that a limited number of MRSA clones have spread globally. However, new findings suggest that SCCmec is transmissible at least in a higher order of magnitude than originally suggested, that MRSA clones are emerging on numerous occasions in distinct locations, and that their geographic dispersals are limited (15). Besides promoting the efforts to restrict the use of antibiotics in livestock feeding, we also have to be vigilant against the dissemination of methicillin-resistant staphylococcal species across animal farms and human society.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bruce E. Allen and Zetty Maztura T. J. Tengku for their help with the editorial preparation of the manuscript. We also thank Hisanobu Miura for help with collecting specimens.

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for 21st-century COE research and a grant-in-aid for scientific research (grant 18590438) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Culture and Technology of Japan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 August 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antignac, A., and A. Tomasz. 2009. Reconstruction of the phenotypes of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by replacement of the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec with a plasmid-borne copy of Staphylococcus sciuri pbpD gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:435-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandler, M., and J. Mahillon. 2002. Insertion sequences revisited, p. 305-366. In N. L. Craig et al. (ed.), Mobile DNA II, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 3.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2009. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 8th ed., vol. 29, p. 2. Approved standard M7-A8. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2009. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 19th informational supplement M100-S19, vol. 29, p. 3. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Couto, I., H. de Lencastre, E. Severina, W. Kloos, J. A. Webster, R. J. Hubner, I. S. Sanches, and A. Tomasz. 1996. Ubiquitous presence of a mecA homologue in natural isolates of Staphylococcus sciuri. Microb. Drug Resist. 2:377-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldburg, R., S. Roach, D. Wallinga, and M. Mellon. 2008. The risks of pigging out on antibiotics. Science 321:1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanssen, A. M., and J. U. Ericson Sollid. 2006. SCCmec in staphylococci: genes on the move. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 46:8-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Working Group on the Classification of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome Elements (IWG-SCC). 2009. Classification of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec): guidelines for reporting novel SCCmec elements. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4961-4967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito, T., Y. Katayama, and K. Hiramatsu. 1999. Cloning and nucleotide sequence determination of the entire mec DNA of pre-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus N315. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1449-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jevons, M. P. 1961. Celbenin-resistant staphylococci. Br. Med. J. 1:124-125. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katayama, Y., T. Ito, and K. Hiramatsu. 2000. A new class of genetic element, staphylococcus cassette chromosome mec, encodes methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1549-1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katayama, Y., T. Ito, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Genetic organization of the chromosome region surrounding mecA in clinical staphylococcal strains: role of IS431-mediated mecI deletion in expression of resistance in mecA-carrying, low-level methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus haemolyticus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1955-1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuroda, M., T. Ohta, I. Uchiyama, T. Baba, H. Yuzawa, I. Kobayashi, L. Cui, A. Oguchi, K. Aoki, Y. Nagai, J. Lian, T. Ito, M. Kanamori, H. Matsumaru, A. Maruyama, H. Murakami, A. Hosoyama, Y. Mizutani-Ui, N. K. Takahashi, T. Sawano, R. Inoue, C. Kaito, K. Sekimizu, H. Hirakawa, S. Kuhara, S. Goto, J. Yabuzaki, M. Kanehisa, A. Yamashita, K. Oshima, K. Furuya, C. Yoshino, T. Shiba, M. Hattori, N. Ogasawara, H. Hayashi, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Whole genome sequencing of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 357:1225-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwok, A. Y., and A. W. Chow. 2003. Phylogenetic study of Staphylococcus and Macrococcus species based on partial hsp60 gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:87-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nübel, U., P. Roumagnac, M. Feldkamp, J. H. Song, K. S. Ko, Y. C. Huang, G. Coombs, M. Ip, H. Westh, R. Skov, M. J. Struelens, R. V. Goering, B. Strommenger, A. Weller, W. Witte, and M. Achtman. 2008. Frequent emergence and limited geographic dispersal of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:14130-14135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliveira, D. C., S. W. Wu, and H. de Lencastre. 2000. Genetic organization of the downstream region of the mecA element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates carrying different polymorphisms of this region. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1906-1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poyart, C., G. Quesne, C. Boumaila, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 2001. Rapid and accurate species-level identification of coagulase-negative staphylococci by using the sodA gene as a target. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4296-4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Queck, S. Y., B. A. Khan, R. Wang, T. H. Bach, D. Kretschmer, L. Chen, B. N. Kreiswirth, A. Peschel, F. R. Deleo, and M. Otto. 2009. Mobile genetic element-encoded cytolysin connects virulence to methicillin resistance in MRSA. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryffel, C., R. Bucher, F. H. Kayser, and B. Berger-Bachi. 1991. The Staphylococcus aureus mec determinant comprises an unusual cluster of direct repeats and codes for a gene product similar to the Escherichia coli sn-glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase. J. Bacteriol. 173:7416-7422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schleifer, K. H., U. Geyer, R. Kilpper-Bälz, and L. A. Devriese. 1983. Elevation of Staphylococcus sciuri subsp. lentus (Kloos et al.) to species status: Staphylococcus lentus (Kloos et al.) comb. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 4:382-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmitz, F. J., M. Steiert, H. V. Tichy, B. Hofmann, J. Verhoef, H. P. Heinz, K. Kohrer, and M. E. Jones. 1998. Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from Dusseldorf by six genotypic methods. J. Med. Microbiol. 47:341-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schnellmann, C., V. Gerber, A. Rossano, V. Jaquier, Y. Panchaud, M. G. Doherr, A. Thomann, R. Straub, and V. Perreten. 2006. Presence of new mecA and mph(C) variants conferring antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus spp. isolated from the skin of horses before and after clinic admission. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:4444-4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stepanovic, S., T. Hauschild, I. Dakic, Z. Al-Doori, M. Svabic-Vlahovic, L. Ranin, and D. Morrison. 2006. Evaluation of phenotypic and molecular methods for detection of oxacillin resistance in members of the Staphylococcus sciuri group. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:934-937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stranden, A., R. Frei, and A. F. Widmer. 2003. Molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: can PCR replace pulsed-field gel electrophoresis? J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3181-3186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Svec, P., M. Vancanneyt, I. Sedlacek, K. Engelbeen, V. Stetina, J. Swings, and P. Petras. 2004. Reclassification of Staphylococcus pulvereri Zakrzewska-Czerwinska et al. 1995 as a later synonym of Staphylococcus vitulinus Webster et al. 1994. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:2213-2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeda, Y., K. Takase, I. Yamato, and K. Abe. 1998. Sequencing and characterization of the xyl operon of a gram-positive bacterium, Tetragenococcus halophila. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2513-2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taubes, G. 2008. The bacteria fight back. Science 321:356-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsubakishita, S., K. Kuwahara-Arai, T. Baba, and K. Hiramatsu. 2010. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec-like element in Macrococcus caseolyticus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1469-1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vernozy-Rozand, C., C. Mazuy, H. Meugnier, M. Bes, Y. Lasne, F. Fiedler, J. Etienne, and J. Freney. 2000. Staphylococcus fleurettii sp. nov., isolated from goat's milk cheeses. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50(Pt. 4):1521-1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webster, J. A., T. L. Bannerman, R. J. Hubner, D. N. Ballard, E. M. Cole, J. L. Bruce, F. Fiedler, K. Schubert, and W. E. Kloos. 1994. Identification of the Staphylococcus sciuri species group with EcoRI fragments containing rRNA sequences and description of Staphylococcus vitulus sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44:454-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilding, E. I., J. R. Brown, A. P. Bryant, A. F. Chalker, D. J. Holmes, K. A. Ingraham, S. Iordanescu, C. Y. So, M. Rosenberg, and M. N. Gwynn. 2000. Identification, evolution, and essentiality of the mevalonate pathway for isopentenyl diphosphate biosynthesis in gram-positive cocci. J. Bacteriol. 182:4319-4327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu, S., H. de Lencastre, and A. Tomasz. 1998. Genetic organization of the mecA region in methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus sciuri. J. Bacteriol. 180:236-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu, S. W., H. de Lencastre, and A. Tomasz. 1999. The Staphylococcus aureus transposon Tn551: complete nucleotide sequence and transcriptional analysis of the expression of the erythromycin resistance gene. Microb. Drug Resist. 5:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]