Abstract

Acinetobacter baumannii is an opportunistic pathogen, especially in intensive care units, and multidrug-resistant isolates have increasingly been reported during the last decade. Despite recent progress in knowledge of antibiotic resistance mechanisms in A. baumannii, little is known about the genetic factors driving isolates toward multidrug resistance. In the present study, the A. baumannii plasmids were investigated through the analysis and classification of plasmid replication systems and the identification of A. baumannii-specific mobilization and addiction systems. Twenty-two replicons were identified by in silico analysis, and five other replicons were identified and cloned from previously uncharacterized A. baumannii resistance plasmids carrying the OXA-58 carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinase. Replicons were classified into homology groups on the basis of their nucleotide homology. A novel PCR-based replicon typing scheme (the A. baumannii PCR-based replicon typing [AB-PBRT] method) was devised to categorize the A. baumannii plasmids into homogeneous groups on the basis of the nucleotide homology of their respective replicase genes. The AB-PBRT technique was applied to a collection of multidrug-resistant A. baumannii clinical isolates carrying the blaOXA-58 or blaOXA-23 carbapenemase gene. A putative complete conjugative apparatus was identified on one plasmid whose self-conjugative ability was demonstrated in vitro. We showed that this conjugative plasmid type was widely diffused in our collection, likely representing the most important vehicle promoting the horizontal transmission of A. baumannii resistance plasmids.

The foundation of plasmid biology was largely built on the genetic analysis of plasmid strategies for broad-host-range replication in Gram-negative bacteria. Mechanisms which guarantee the autonomous replication, addiction systems based on toxin-antitoxin factors, partitioning systems ensuring stable inheritance during cell division, and other virulence and antimicrobial resistance determinants have been described for plasmids circulating in the Enterobacteriaceae family and Pseudomonas spp. (17). Enterobacterial plasmids have also been classified into homogeneous groups on the basis of their replication controls by conjugation (plasmid incompatibility) and molecular methods (Southern blot hybridization with replicon probes and PCR-based replicon typing) (5, 8, 10, 11). Currently, 27 incompatibility groups are recognized in the Enterobacteriaceae by the Plasmid Section of the National Collection of Type Cultures (Colindale, London, United Kingdom). In contrast, limited information is available on the plasmids circulating in Acinetobacter spp., even though Acinetobacter baumannii is an important pathogen in intensive care units (13, 28). Moreover, despite recent progress in the study of antibiotic resistance mechanisms in A. baumannii, little is known about the genetic factors that have driven the recent evolution of A. baumannii toward multidrug resistance. A. baumannii may develop resistance to carbapenems through plasmid-mediated acquisition of carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamases (CHDLs) (29). In particular, the blaOXA-58 and blaOXA-23 genes encoding the OXA-58 and OXA-23 CHDLs, respectively, have been reported from A. baumannii isolates collected from distant parts of the world in association with plasmids. The aim of the present study was to investigate the A. baumannii plasmids through the analysis and classification of plasmid replication systems and identification of A. baumannii-specific mobilization and addiction systems. Finally, novel tools for detecting A. baumannii resistance plasmids are proposed and the plasmids are categorized into homogeneous families on the basis of the nucleotide homologies of their respective replicase genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In silico analysis of A. baumannii plasmids.

An in silico comparative analysis of fully and partially sequenced Acinetobacter plasmids was performed at GenBank using the BLAST program (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Fifteen fully sequenced and eight partially sequenced A. baumannii plasmids available at GenBank from six completed genomes from previous studies or identified in this study were analyzed (Table 1). Multiple-sequence alignments of the replicon nucleotide sequences have been performed using DNAMAN software (Lynnon BioSoft, Vaudreuil, Quebec, Canada) set for DNA quick alignment with a gap penalty of 7, a K-tuple of 3, 5 top diagonals, and a window size of 5. Multiple-sequence alignments of the coding sequences were performed by using the DNAMAN software set for protein quick alignment with a gap penalty of 3, a K-tuple of 1, five top diagonals, and a window size of 5.

TABLE 1.

A. baumannii replicase genes analyzed in this study

| Strain | Plasmid (EMBL accession no.) | Replicase name | Rep superfamily | Source of homology by BLASTp best hita | % amino acid identity (EMBL accession no.) | Iteronsb | Rep group | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACICU | pACICU1 (NC_010605) | Aci1 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Klebsiella pneumoniae pKPN5 | 71 (YP_001338806) | Pos | GR2 | 19 |

| AciX | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Neisseria lactamica | 55 (ZP_05987942) | Pos | GR10 | |||

| pACICU2 (NC_010606) | Aci6 | Rep pfam03090 | Pseudoalteromonas sp. | 41 (YP_001887739) | Neg | GR6 | ||

| SDF | p1ABSDF (NC_010395) | p1ABSDF0001 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Moraxella bovis | 59 (YP_001966359) | Pos | GR1 | 34 |

| p2ABSDF (NC_010396) | p2ABSDF0001 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Moraxella bovis | 40 (YP_003289297) | Pos | GR12 | ||

| p2ABSDF0025 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Moraxella bovis | 50 (YP_003289297) | Pos | GR18 | |||

| p3ABSDF (NC_010398) | p3ABSDF0002 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Klebsiella pneumoniae pKPN5 | 57 (YP_001338806) | Neg | GR7 | ||

| p3ABSDF0009 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Klebsiella pneumoniae pKPN5 | 45 (YP_001338806) | Pos | GR9 | |||

| p3ABSDF0018 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Moraxella bovis | 41 (YP_003289297) | Pos | GR15 | |||

| AYE | p1ABAYE (NC_010401) | p1ABAYE0001 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Enhydrobacter aerosaccus | 33 (ZP_05619518) | Pos | GR11 | 34 |

| p2ABAYE (NC_010402) | p2ABAYE0001 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Klebsiella pneumoniae pKPN5 | 71 (YP_001338806) | Pos | GR2 | ||

| p3ABAYE (NC_010404) | p3ABAYE0002 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Pasteurella multocida pJR2_p4 | 31 (NP_848174) | Neg | GR13 | ||

| p4ABAYE (NC_010403) | p4ABAYE0001 | Rep-1 pfam01446 | Pseudomonas putida | 43 (NP_064737) | Neg | GR14 | ||

| ATCC 17978 | pAB1 (NC_009083) | A1S_3471 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Klebsiella pneumoniae pKPN5 | 59 (YP_001338806) | Pos | GR17 | 32 |

| pAB2 (NC_009084) | A1S_3472 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Klebsiella pneumoniae pKPN5 | 71 (YP_001338806) | Pos | GR2 | ||

| Ab0057 | pAB0057 (NC_011585) | AB57_3921 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Klebsiella pneumoniae pKPN5 | 71 (YP_001338806) | Pos | GR2 | 1 |

| Ab49 | pAB49 (L77992; partial) | repApAB49 | Rep-1 pfam01446 | Bacillus cereus | 38 (ZP_04189469) | Neg | GR16 | Unpublished |

| AbABIR | pABIR (EU294228) | RepA_AB | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Moraxella bovis | 40 (YP_003289297) | Pos | GR12 | 35 |

| VA-566/00 | pABVA01 (NC_012813) | Aci2 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Klebsiella pneumoniae pKPN5 | 74 (YP_001338806) | Pos | GR2 | 9 |

| Ab19606 | pMAC02 (AY541809) | RepM-Aci9 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Klebsiella pneumoniae pKPN5 | 57 (YP_001338806) | Pos | GR8 | 12 |

| Ab02 | pAB02 (AY228470, partial) | repA_AB | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Moraxella bovis | 40 (YP_003289297) | Pos | GR12 | Unpublished |

| Ab135040 | p135040 (GQ861437, partial) | rep135040 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Klebsiella pneumoniae pKPN5 | 58 (YP_001338806) | Pos | GR19 | 18 |

| Ab736 | p736 (GU978996; partial) | Aci7 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Klebsiella pneumoniae pKPN5 | 92 (YP_001338806) | Pos | GR3 | This study |

| Ab203 | P203 (GU978997; partial) | Aci3 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Klebsiella pneumoniae pKPN5 | 85 (YP_001338806) | Pos | GR3 | This study |

| Ab844 | p844 (GU978998; partial) | Aci4 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Klebsiella pneumoniae pKPN5 | 85 (YP_001338806) | Pos | GR4 | This study |

| Ab537 | p537 (GU978999; partial) | Aci5 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Klebsiella pneumoniae pKPN5 | 72 (YP_001338806) | Pos | GR5 | This study |

| Ab11921 | p11921 (GU979000; partial) | Aci8 | Rep-3 pfam01051 | Klebsiella pneumoniae pKPN5 | 46 (YP_001966359) | Pos | GR8 | This study |

This comparison was performed by a BLASTP search excluding the sequence of the Acinetobacter spp.

Pos, positive; Neg, negative.

A. baumannii PCR-based replicon typing (AB-PBRT) method.

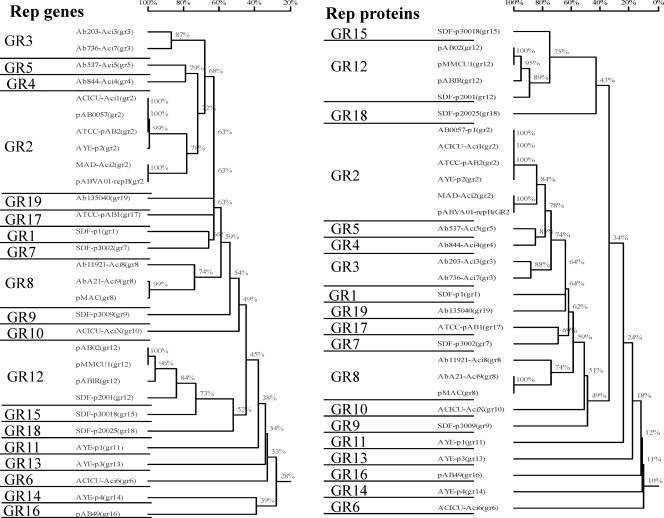

A total of 19 PCR amplifications were devised to detect 27 replicase genes, which were grouped into 19 homology groups (GRs) on the basis of their nucleotide sequence similarities (Table 1 and Fig. 1). These groups include five novel replicase genes (aci3, aci4, aci5, aci7, and aci8 [Table 1]), cloned and sequenced as described below, from plasmids carrying the blaOXA-58 genes from a collection of A. baumannii clinical isolates.

FIG. 1.

Multiple-sequence alignments and groups of homology of the replicase genes and their deduced amino acid protein sequences from A. baumannii plasmids.

The primers used for AB-PBRT are listed in Table 2. The PCR amplifications were organized into six multiplexes, each recognizing three or four different homology groups (Table 2). Specificity and sensitivity tests were performed for each primer pair in simplex form and in multiplex form with genomic DNA extracted from the respective reference strain (Table 2). The multiplexes were also tested using single and mixed control DNA templates. All the PCRs were highly specific on each template, as expected. The PCRs for GR2, GR3, and GR8 recognize the related replicases Aci1/Aci2, Aci3/Aci7, and Aci8/Aci9, respectively. The replicase variants belonging to GR2, GR3, and GR8 can be recognized by DNA sequencing of the respective amplicon.

TABLE 2.

Primers used to detect the replicase gene groups in the A. baumannii PCR-based replicon typing scheme

| Multiplex | Group | Primer name | Primer sequence | Amplicon size (bp) | Replicase name (short name) | Reference strain/plasmid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | gr1FW | 5′-CATAGAAATACAGCCTATAAAG-3′ | 330 | p1ABSDF001 (p1S1) | SDF-p1ABSDF | |

| gr1RV | 5′-TTCTTCTAGCTCTACCAAAAT-3′ | |||||

| GR2 | gr2FW | 5′-AGTAGAACAACGTTTAATTTTATTGGC-3′ | 851 | Aci1 | ACICU-pACICU1 | |

| gr2RV | 5′-CCACTTTTTTTAGGTATGGGTATAG-3′ | Aci2 | MAD | |||

| GR3 | gr3FW | 5′-TAATTAATGCCAGTTATAACCTTG-3′ | 505 | Aci3 | Ab599 | |

| gr3RV | 5′-GTATCGAGTACACCTATTTTTTGT-3′ | Aci7 | Ab736 | |||

| 2 | GR5 | gr5FW | 5′-AGAATGGGGAACTTTAAAGA-3′ | 220 | Aci5 | Ab537 |

| gr5RV | 5′-GACGCTGGGCATCTGTTAAC-3′ | |||||

| GR18 | gr18FW | 5′-TCGGGTTATCACAATAACAA-3′ | 676 | p2ABSDF00025 (p2S25) | SDF-p2ABSDF | |

| gr18RV | 5′-TAGAACATTGGCAATCCATA-3′ | |||||

| GR7 | gr7FW | 5′-GAACAGTTTAGTTGTGAAAG-3′ | 885 | p3ABSDF002 (p3S2) | SDF-p3ABSDF | |

| gr7RV | 5′-TCTCTAAATTTTTCAGGCTC-3′ | |||||

| 3 | GR9 | gr9FW | 5′-GCAAGTTATACATTAAGCCT-3′ | 191 | p3ABSDF0009 (p3S9) | SDF-p3ABSDF |

| gr9RV | 5′-AAAAATAAACGCTCTGATGC-3′ | |||||

| GR4 | gr4FW | 5′-GTCCATGCTGAGAGCTATGT-3′ | 508 | Aci4 | Ab844 | |

| gr4RV | 5′-TACGTCCCTTTTTATGTTGC-3′ | |||||

| GR11 | gr11FW | 5′-GGCTATTCAAAACAAAGTTAC-3′ | 852 | p1ABAYE0001 (p1AYE) | AYE-p1ABAYE | |

| gr11RV | 5′-GTTTCCTCTCTTACACTTTT-3′ | |||||

| 4 | GR12 | gr12FW | 5′-TCATTGGTATTCGTTTTTCAAAACC-3′ | 165 | p2ABSDF0001 (p2S1) | SDF-p1ABSDF |

| gr12RV | 5′-ATTTCACGCTTACCTATTTGTC-3′ | |||||

| GR10 | gr10FW | 5′-TTTCACTAGCTACCAACTAA-3′ | 371 | AciX | ACICU-pACICU1 | |

| gr10RV | 5′-ACACGTTGGTTTGGAGTC-3′ | |||||

| GR13 | gr13FW | 5′-CAAGATCGTGAAATTACAGA-3′ | 780 | p3ABAYE0002 (p3AYE) | AYE-p3ABAYE | |

| gr13RV | 5′-CTGTTTATAATTTGGGTCGT-3′ | |||||

| 5 | GR8 | gr8FW | 5′-AATTAATCGTAAAGGATAATGC-3′ | 233 | Aci8 | Ab11921 |

| gr8RV | 5′-GACATAGCGATCAAATAAGC-3′ | repM (Aci9) | pMAC02 | |||

| GR14 | gr14FW | 5′-TTAAATGGGTGCGGTAATTT-3′ | 622 | p4ABAYE0001 (p4AYE) | AYE-p4ABAYE | |

| gr14RV | 5′-GCTTACCTTTCAAAACTTTG-3′ | |||||

| GR15 | gr15FW | 5′-GGAAATAAAAATGATGAGTCC-3′ | 876 | p3ABSDF0018 (p3S18) | SDF-p3ABSDF | |

| gr15RV | 5′-ATAAGTTGTTTTTGTTGTATTCG-3 | |||||

| 6 | GR16 | gr16FW | 5′-CTCGAGTTCAGGCTATTTTT-3′ | 233 | repApAB49 (pAB49) | pAB49 |

| gr16RV | 5′-GCCATTTCGAAGATCTAAAC-3′ | |||||

| GR17 | gr17FW | 5′-AATAACACTTATAATCCTTGTA-3′ | 380 | A1s_3471 (A1S3471) | ATCC 17978-pAB1 | |

| gr17RV | 5′-GCAAATGTGACCTCTAATATA-3′ | |||||

| GR6 | gr6FW | 5′-AGCAAGTACGTGGGACTAAT-3′ | 662 | Aci6 | ACICU-pACICU2 | |

| gr6RV | 5′- AAGCAATGAAACAGGCTAAT-3′ | |||||

| GR19 | gr19FW | 5′- ACGAGATACAAACATGCTCA-3′ | 815 | rep135040 | Ab135040 | |

| gr19RV | 5′- AGCTAGACATTTCAGGCATT-3′ |

Each multiplex reaction mixture contained (final concentrations) 1× ImmoBuffer [16 mM (NH4)2SO4, 67 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 0.01% Tween 20], 4.0 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1.0 μM each primer, 5% dimethyl sulfoxide, 0.04 U/μl Immolase DNA polymerase (Bioline, Kondon, United Kingdom), and 200 to 400 ng of DNA template per reaction tube. Template DNA was prepared by total DNA extraction by the Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI), starting from 2 ml of LB broth cultures. PCR amplifications were performed with the following amplification scheme: 1 cycle of denaturation at 94°C for 7 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 52°C for 30 s, and elongation at 72°C for 1.5 min. The amplification was finished with an extension program of 1 cycle at 72°C for 5 min.

Positive controls.

The PCR amplifications were tested with the ACICU, AYE, SDF, ATCC 19798, and Ab135040 reference strains and 20 nonclonally related A. baumannii isolates known to possess plasmids carrying the CHDL gene blaOXA-58 (n = 13, originating from France, Tunisia, Sweden, Turkey, Romania, and Belgium) or blaOXA-23 (n = 7, originating from Belgium, Monaco, Kingdom of Bahrain, Egypt, Algeria, Libya, and Saudi Arabia). Those carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii isolates had been characterized previously (23, 25, 26, 30) and belong to the INSERM U914 strain collection (Table 3). Plasmid typing was also performed with transformants and transconjugants obtained from the blaOXA-58- and blaOXA-23-positive plasmids (Table 3). All the amplicons obtained with the primers listed in Table 2 were cloned into a TA cloning vector (Invitrogen-Life Technologies, Milan, Italy) and transformed into competent Escherichia coli DH5α cells (MAX Efficiency DH5α chemically competent cells; Invitrogen-Life Technologies). Selection of the transformants was performed on LB agar plates containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml). The cloned amplicons were fully sequenced and used as positive controls for the multiplex PCRs in the AB-PBRT scheme.

TABLE 3.

AB-PBRT applied to the collection of blaOXA-58- and blaOXA-23-positive strains and their respective transformants/transconjugants

| Strain | OXA | Multiplex 1 |

Multiplex 2 |

Multiplex 3 |

Multiplex 4 |

Multiplex 5 |

Multiplex 6 |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GR2 (851 bp) | GR3 (505 bp) | GR1 (330 bp) | GR7 (885 bp) | GR18 (676 bp) | GR5 (220 bp) | GR11 (852 bp) | GR4 (508 bp) | GR9 (191 bp) | GR13 (780 bp) | GR10 (371 bp) | GR12 (165 bp) | GR15 (876 bp) | GR14 (622 bp) | GR8 (233 bp) | GR6 (662 bp) | GR17 (425 bp) | GR16 (233 bp) | GR19 (815 bp) | ||

| ACICU | 58 | Aci1 | AciX | Aci6 | ||||||||||||||||

| AYE | p2AYE (Aci1) | p1AYE | p3AYE | p4AYE | ||||||||||||||||

| SDF | Aci3b | p1S1 | p3S2 | p2S1 | p3S9 | p2S25 | p3S18 | |||||||||||||

| ATCC | A1S_3472 (Aci1) | A1S3471 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 135040T | 143 | Rep | ||||||||||||||||||

| A21 | 58 | Aci1 | p2S25 | Aci9 | Aci6 | pAB49 | ||||||||||||||

| A21Ta | 58 | [Aci5]c | [Aci4] | Aci9 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ab11921 | 58 | Aci1 | p2S25 | Aci8 | ||||||||||||||||

| 11921Ta | 58 | [Aci5] | [Aci4] | Aci8 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ab203 | 58 | Aci3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 203Ta | 58 | Aci3 | [Aci5] | [Aci4] | ||||||||||||||||

| Ab844 | 58 | Aci2 | Aci4 | p2S25 | Aci6 | |||||||||||||||

| 844Ta | 58 | [Aci5] | Aci4 | |||||||||||||||||

| Ab537 | 58 | Aci3 | Aci5 | Aci4 | ||||||||||||||||

| 537Ta | 58 | Aci3 | [Aci5] | [Aci4] | ||||||||||||||||

| MAD | 58 | Aci2 | Aci6 | |||||||||||||||||

| MADTa | 58 | Aci2 | [Aci5] | [Aci4] | ||||||||||||||||

| Ab736 | 58 | Aci7 | Aci6 | |||||||||||||||||

| 736Ta | 58 | Aci7 | [Aci5] | [Aci4] | ||||||||||||||||

| Ab727 | 58 | Aci1 | Aci6 | pAB49 | ||||||||||||||||

| 727Ta | 58 | Aci1 | [Aci5)] | [Aci4] | ||||||||||||||||

| AbA22 | 58 | Aci1 | Aci6 | pAB49 | ||||||||||||||||

| A22Ta | 58 | Aci1 | [Aci5)] | [Aci4] | ||||||||||||||||

| Ab120066 | 58 | Aci1 | AciX | Aci6 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ab587 | 58 | Aci3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 587Ta | 58 | Aci3 | [Aci5] | [Aci4] | ||||||||||||||||

| Ab692 | 58 | Aci3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 692Ta | 58 | Aci3 | [Aci5] | [Aci4] | ||||||||||||||||

| Ab599 | 58 | Aci2 | Aci3 | p2S25 | ||||||||||||||||

| 599Ta | 58 | Aci3 | [Aci5] | [Aci4] | ||||||||||||||||

| AbAS3 | 23 | p2S25 | Aci6 | |||||||||||||||||

| AS3TcJa | 23 | [Aci5] | [Aci4] | Aci6 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ab1190 | 23 | p2S25 | Aci6 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1190Tcja | 23 | [Aci5] | [Aci4] | Aci6 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ab614 | 23 | p2S25 | Aci6 | |||||||||||||||||

| 614Tcja | 23 | [Aci5] | [Aci4] | Aci6 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ab861 | 23 | Aci1 | Aci6 | |||||||||||||||||

| 861Tcja | 23 | [Aci5] | [Aci4] | Aci6 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ab877 | 23 | Aci4 | Aci6 | |||||||||||||||||

| Ab14 | 23 | Aci6 | ||||||||||||||||||

| AbBel | 23 | Aci1 | Aci6 | |||||||||||||||||

| Recipient | [Aci5] | [Aci4] | ||||||||||||||||||

blaOXA-positive transformants (T) and transconjugants (Tcj) were obtained from the respective donor strain indicated on the line above the transformant or transconjugant designation using A. baumannii BM4547 as the recipient.

The aci3 gene was not identified in the whole-genome sequencing of the SDF strain.

Brackets indicate that Aci4 and Aci5 replicases are present in the recipient strain.

Plasmid transfer by transformation and conjugation.

Plasmid DNAs were purified from blaOXA-58-positive A. baumannii isolates by using an Invitrogen PureLink HiPure plasmid filter midiprep kit and electrotransformed into recipient strain A. baumannii BM4547 (22), and transformants were selected on ticarcillin-containing plates (50 μg/ml). Mating-out assays were performed by using isolates harboring blaOXA-58 and blaOXA-23 plasmids as donors and rifampin-resistant recipient strain A. baumannii BM4547, as described previously (26). Briefly, one colony of each of the donor and recipient strains obtained after 24 h of growth was cultured separately under weak agitation in 1 ml tryptic soy broth at 37°C, and they were then used in the mating-out assays. Conjugation was done by incubating 800 μl of the recipient strain with 200 μl of the donor strain under low agitation at 37°C for an additional 3-h step. The transconjugants were then selected by plating 200 μl of that mixture on agar plates containing ticarcillin (100 μg/ml) and rifampin (50 μg/ml).

The blaOXA-58 and blaOXA-23 genes were detected by PCR using previously described primer pairs (2, 7).

Identification and cloning of novel replicase genes from A. baumannii plasmids.

Plasmid DNAs were purified from the A. baumannii transformants by the Invitrogen PureLink HiPure plasmid filter midiprep kit. EcoRI-restricted fragments were separated by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. Plasmid DNA was transferred to a Hybond-N+ membrane (Roche Diagnostics, Monza, Italy) by standard methods (31). Southern blot hybridization was carried out under low-stringency conditions (58°C) using the aci1 amplicon from the pACICU1 plasmid as the probe, and the amplicon was labeled with digoxigenin (DIG)-11-dUTP by PCR using a DIG PCR probe synthesis kit (Roche Diagnostics, Monza, Italy). After hybridization with the probe, the hybridized DNA was detected with Nitro Blue Tetrazolium-5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate using a DIG nucleic acid detection kit (Roche Diagnostics).

The EcoRI-restricted fragments identified by cross-reaction with the aci1 probe were separated by and eluted from the agarose gel by a Qiagen (Courtaboeuf, France) gel extraction kit and cloned into the EcoRI cloning site of the pUC18 vector, and the vector was transformed into competent E. coli DH5α cells (MAX Efficiency DH5α chemically competent cells; Invitrogen, Milan, Italy). Selection of the transformants was performed on LB agar plates containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml). The inserts were fully sequenced using standard and walking primers. The DNA sequences were determined by used of fluorescent dye-labeled dideoxynucleotides and an AB3730 automatic DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The DNA sequences of the aci3, aci4, aci5, aci7, and aci8 replicase genes and the aci9 replicase gene from plasmid AbA21 have been deposited in the EMBL GenBank under accession numbers GU978996 to GU979001, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Detailed analysis and definitions of A. baumannii replicons.

The nucleotide and deduced protein sequences of 18 A. baumannii plasmids available in GenBank were analyzed. Twenty-two intact replicons were identified in silico (Table 1). Each replicon included the origin of replication (ori) and the replicase gene (rep). A. baumannii replicons differ from all those previously described in other prokaryotic species, indicating that A. baumannii possesses its own plasmid types. For 17 out of the 22 replicons, the rep genes were preceded by four direct and perfectly conserved repeats that, in analogy with the basic replicons of plasmids, may be defined as “iterons” (Table 1 and Table 4). Iterons have been identified not only on many prokaryotic plasmids but also on chromosomes, phages, and eukaryotic ori genes (6, 27). In enterobacterial plasmids, each replicase protein binds to the reiterated iterons at the ori site and stimulates DNA replication by interacting with the host proteins (DNAK, DNAJ, RNApol) required for replication initiation. However, no iterons were identified in association with the replicase genes for five plasmids. For these plasmids, one can speculate about alternative mechanisms of replication control, presumably based on regulation of rep translation mediated by an inhibitory antisense RNA, as previously described for IncI1 and IncF plasmids (14).

TABLE 4.

Iterons in A. baumannii replicons

| Replicon(s) | Iteron sequence | No. of direct repeats | Distance from iteron to rep start codon (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| p1ABSDF0001 | 5′-CAATAAGTACACCTTTATCTTG-3′ | 4 | 50 |

| pACICU1-Aci1, p2ABAYE0001, A1S_3472 pAB0057 | 5′-ATATGTCCACGTTTACCTTGCA-3′ | 4 | 53 |

| pABVA01-Aci2 | 5′-TTTACCTTGCAATATGACACCG-3′ | 3 | 66 |

| Ab203-Aci3 | 5′-TAAAACGAGGTTTACCTTGCAT-3′ | 4 | 57 |

| Ab736-Aci7 | |||

| Ab844-Aci4 | 5′-ATATGACTACGTTTACCTACCA-3′ | 4 | 107 |

| Ab537-Aci5 | 5′-ATATGACTACGTTTACCTACCA-3′ | 4 | 105 |

| Ab11921-Aci8 | 5′-TAGGTTTATCGACCCATAAAAT-3′ | 4 | 91 |

| pA21-Aci9 | 5′-TAAAACTAGGTTTATCGACCCT-3′ | 4 | 96 |

| pMAC-Aci9 | 5′-ATAAAACTAGGTTTATCGACCC-3′ | 4 | 97 |

| p3ABSDF0009 | 5′-TATCTATACGTTTATGCAGTCT-3′ | 4 | 60 |

| pACICU1-AciX | 5′-CATTCAATCACAGATTCCATTC-3′ | 4 | 80 |

| p1ABAYE0001 | 5′-AAAGGGTACAAATAGCATGAT-3′ | 4a | 90 |

| p2ABSDF0001, pAB02 | 5′-GGATTGACTACTAACTATGAC-3′ | 4 | 41 |

| pABIR | 5′-CTAACTATGACGGATTGACTA-3′ | 4 | 55 |

| p3ABSDF0018 | 5′-TATGAGGGATTGACTACTAAC-3′ | 4 | 32 |

| pAB1 | 5′-ATTTCTTTGCATTTGACTACA-3′ | 4 | 10 |

| p2ABSDF0025 | 5′-TAACTATGAGGGATTGACGCA-3′ | 5 | 15 |

| p135040 | 5′-CATAT CTATACGTTTATCGACC-3′ | 4 | 89 |

Imperfect.

Similar to plasmids described from other species (33), A. baumannii pACICU1, p2ABSDF, and p3ABSDF were multireplicon plasmids, since they carried more than one replicon (Table 1). Interestingly, the iterons and replicase genes of replicons from given plasmids showed weak sequence identities, likely to minimize the effect of competition of the replicase protein on its relative binding sites (6, 27). Plasmids pABIR and pABVA01 also showed two replicons, one that was functional, which was considered in this study, and one whose replicase gene was truncated by an insertion sequence (EMBL accession no. EU294228).

On the basis of the nucleotide sequence identities deduced from the in silico analysis, the 22 replicase genes were grouped into homology groups. Each group showed replicase genes showing less than 74% nucleotide identity (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Plasmids p2ABSDF, pABIR (carrying the blaOXA-58 gene), and pAB02 (carrying the blaOXA-24/OXA-40 gene) carried highly related replicons which were included in the same homology group, designated GR12, showing conserved replicase gene and iteron sequences (>84% nucleotide identity; Fig. 1 and Table 4). This group also contains other plasmids carrying the blaOXA-24/OXA-40 gene that were recently identified and that showed rep gene sequences identical to the rep gene sequences of pAB02 (pMMCU1 [EMBL accession no. GQ342610], pMMCU2 [EMBL accession no. GQ476987], and pMMD [EMBL accession no. GQ904226]; the sequence of plasmid pMMCU1 is included in the tree in Fig. 1 for comparison).

Conserved replicons were observed for plasmids pACICU1, p2ABAYE, pAB2, pAB0057, pABVA01, and pMAD; and all have been included in GR2. Two variants (aci1 and aci2) showing 78% nucleotide identity were included in this group (Fig. 1). This group also contains plasmid pMMCU3 (EMBL accession no. GQ904227), carrying the blaOXA-24/OXA-40 gene, which had a aci2 rep gene sequence identical to that of pABVA01 (9, 24). The aci1 and aci2 replicase genes showed different iteron sequences (Table 4).

Most of the replicase proteins belonged to the Rep-3 superfamily, identified by the pfam0151 conserved domain (NCBI nonredundant Clusters of Orthologs [COG]; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/), and showed variable amino acid similarities with the replicase proteins of plasmid pKPN5, recently identified in Klebsiella pneumoniae strain MGH 78578 (GenBank accession no. CP000650.1), and with plasmids identified in Moraxella bovis, Pasteurella multocida, and Neisseria lactamica (Table 1). It may be hypothesized that these replicase genes actually derive from a common ancestor of the Rep-3 superfamily group (Table 1). Two replicase proteins from plasmids p4ABAYE and pAB49 belonged to the Rep-1 superfamily (pfam01446) and showed significant homologies with plasmids from Pseudomonas putida and Bacillus cereus. The replicase from plasmid pACICU2 was peculiar since it belonged to an undefined Rep superfamily (pfam03090) whose closest homologous plasmid was identified from a Pseudoalteromonas sp. (Table 1).

Setup of a novel A. baumannii PCR-based replicon typing scheme.

PCR amplifications were devised to recognize the replicase genes identified in silico and were successfully tested with the ACICU, AYE, SDF, ATCC 19798, and Ab135040 A. baumannii strains (Tables 2 and 3). Those PCRs were then used to test 20 clinical isolates carrying the plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing blaOXA-58 and blaOXA-23 oxacillinase genes (Table 3). Mating-out assays were initially performed with several blaOXA-58-positive A. baumannii isolates as donors, but no transconjugants were obtained. However, all the blaOXA-58-positive plasmids except one (from strain Ab120066) were successfully transferred by electroporation into A. baumannii BM4547 (Table 3). Transformants showed resistance to ticarcillin and reduced susceptibility to carbapenems as a result of blaOXA-58 gene expression. Four out of seven blaOXA-23-positive plasmids were successfully transferred by conjugation into A. baumannii BM4547 and included in this study (Table 3) (26). All the A. baumannii isolates and their respective transformants and transconjugants were previously tested by the PCR-based replicon typing method described for the Enterobacteriaceae (5), but all of them gave negative results, indicating that those plasmids were not corresponding to those known to circulate among the Enterobacteriaceae (data not shown).

Twelve strains and their respective blaOXA-58 or blaOXA-23 transformant or transconjugant strains were successfully typed by the PCR amplifications devised with the 22 A. baumannii replicase genes identified in silico in previously characterized plasmids (Table 1). Four blaOXA-58-positive strains and their respective transformants (strains Ab203, Ab537, Ab587, and Ab692) were negative by all these PCRs. Furthermore, strains Ab11921, Ab844, Ab736, and Ab599 were positive by the GR12 and/or GR6 PCR, but their respective transformants, carrying the blaOXA-58 gene, were negative for all the A. baumannii replicase genes identified in silico, suggesting that other replicons were present on these blaOXA-58-positive plasmids.

Five novel replicase genes (aci3, aci4, aci5, aci7, and aci8 [Table 1]) were identified and subsequently cloned and sequenced from the blaOXA-58-positive strains: the aci8 rep gene from plasmid p11921 was 74% homologous to the repM replicase gene from plasmid pMAC02 and was included in GR8; aci3 and aci7 corresponded to novel replicase genes identified in plasmids from isolates Ab203, Ab537, Ab587, Ab599 (aci3), and Ab736 (aci7). The aci3 and aci7 rep genes showed 87% nucleotide identity with each other and identical iteron sequences and were grouped into a novel homology group designated GR3; the aci4 and aci5 replicase genes from isolates Ab844 and Ab537, respectively, were classified in the novel groups GR4 and GR5, respectively, being highly divergent from all the other replicase genes (Fig. 1; Table 1). Noteworthy is the finding that the BM4547 strain used as the susceptible recipient for transformation and conjugation was positive for the aci4 and aci5 replicase genes, probably due to the integration of a multireplicon plasmid within the bacterial chromosome, since no extrachromosomal plasmids were identified for that strain (data not shown). Southern blot hybridization experiments performed with plasmid DNA purified from the 844T transformant confirmed that this blaOXA-58 plasmid possessed the aci4 replicase gene (data not shown).

In conclusion, the AB-PBRT scheme for A. baumannii plasmid typing showed that donor strains often carried more than one plasmid type. However, each transformant or transconjugant carrying the blaOXA-58 or blaOXA-23 gene carried only a single replicon that was also identified from its corresponding donor strain by the AB-PBRT scheme.

AB-PBRT applied to our collection of A. baumannii strains demonstrated that the blaOXA-58-positive plasmids differed, with six of them showing replicons belonging to GR3, including both the aci3 and aci7 replicase genes. A previously unidentified replicase of GR3 was also identified in the SDF strain. Three blaOXA-58-positive plasmids carried the aci1 or aci2 replicase gene, belonging to GR2, and two plasmids carried the aci8 or aci9 gene, belonging to GR8. Interestingly, the AbA21 plasmid showed a replicase 99% homologous to the repM-aci9 gene of pMAC02 but carried a different iteron sequence (Table 4). All isolates carrying the blaOXA-23 gene showed a positive PCR result for the aci6 replicase gene, which was originally identified on plasmid pACICU2.

In silico analysis of A. baumannii plasmid maintenance and inheritance.

As extrachromosomal elements, plasmids bear the burden of ensuring their own segregation at cell division and employ various strategies, such as active partition systems and postsegregational killing mechanisms. These systems have never been described for A. baumannii plasmids. A careful annotation of the coding sequences from fully sequenced plasmids allowed the identification of putative ParA and ParB (3) partitioning proteins on plasmids pACICU1, pACICU2, and p3ABAYE (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Plasmid maintenance and addiction systems identified in silico on A. baumannii plasmids

| Predicted function | Plasmid | CDSa protein identifier | Protein name, putative function | Source of homology | % best hit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid partitioning | pACICU1 | P006 | ParA, putative partition protein | Moraxella bovis | 73 |

| pACICU1 | P007 | Probable copy no. control protein | Moraxella bovis | 56 | |

| pACICU2 | P0040 | ParB, involvement in plasmid partition | Collimonas fungivorans | 44 | |

| pACICU2 | P0047 | ParA, putative partition protein | uncultured bacterium | 34 | |

| pACICU2 | P0048 | ParB-like nuclease domain | Caminibacter mediatlanticus | 39 | |

| p3ABAYE | p3ABAYE0112 | ParB- nuclease domain | Ralstonia eutropha | 41 | |

| p3ABAYE | p3ABAYE0113 | ParA, putative partitioning protein | Chromobacterium violaceum | 38 | |

| Toxin-antitoxin systems | pACICU1 | P009 | Antitoxin StbE, prevent-host-death protein | Burkholderia ubonensis | 57 |

| pACICU1 | P0010 | Toxin RelE/StbE family | Burkholderia ubonensis | 61 | |

| p1ABAYE | p1ABAYE0004 | Antitoxin, prevent-host-death protein | Burkholderia cenocepacia | 56 | |

| p1ABAYE | p1ABAYE0005 | Toxin, Txe/YoeB family | Burkholderia ambifaria | 70 | |

| p2ABSDF | p2ABSDF0030 | Toxin, RelE family protein | Haemophilus somnus | 62 | |

| p2ABSDF | p2ABSDF0031 | Antitoxin, RelB homolog of RelB/DinJ family | Haemophilus somnus | ||

| Restriction and antirestriction systems | pACICU1 | P008 | Type I site-specific DNase, HsdR family | Chlorobium limicola | 33 |

| pACICU2 | P0046 | Type I restriction enzyme M subunit | Haemophilus influenzae | 28 | |

| p3ABAYE | p3ABAYE0069 | Type II restriction/modification enzyme | Polaromonas sp. | 52 | |

| p2ABSDF | p2ABSDF0015 | HpaII restriction endonuclease | Flavobacterium psychrophilum | 49 | |

| p2ABSDF | p2ABSDF0016 | HpaIIM-like cytosine-specific methyltransferase, modification enzyme | Haemophilus arainfluenzae | 79 | |

| p3ABSDF | p3ABSDF0013 | Type II restriction/modification enzyme | Bacillus megaterium | 55 | |

| p3ABSDF | p3ABSDF0014 | Methyltransferase cytosine, modification enzyme | Bacillus megaterium | 46 | |

| p3ABSDF | p3ABSDF0015 | Bfii restriction endonuclease | Bacillus firmus | 63 |

CDS, coding sequence.

Plasmids pACICU1, p1ABAYE, and p2ABSDF encoded putative postsegregational killing systems. In particular, the orthologs of the RelBE toxin-antitoxin system of plasmids from Escherichia coli (20) were identified on pAUCU1 and p2ABSDF, while the orthologs of the Txe system of plasmid pRUM of Enterococcus faecium (16) were identified on the p1ABAYE plasmid (Table 5).

Plasmids pACICU1, pACICU2, p3ABAYE, p2ABSDF, and p3ABSDF also encoded putative restriction and antirestriction systems, including type I and type II restriction/modification enzymes, the HpaII and Bfii endonucleases, and their specific antirestriction methyltransferases (Table 5).

A. baumannii plasmid transferability.

Bacterial conjugation is one of the fundamental processes used for gene dissemination in nature. A putative conjugative system was identified only for plasmid pACICU2 (Table 6). This system is homologous to a conjugative system identified for uncharacterized plasmids of Burkholderia cenocepacia and Burkholderia thailandensis, suggesting a potential common origin of ancestor plasmids among these bacteria. The conjugative system of plasmid pACICU2 also showed a protein equivalent to the relaxase-helicase (TraI) belonging to a novel clade of the MOBF family of relaxase proteins previously described for other transmissible plasmids from the prokaryotic kingdom (15, 21).

TABLE 6.

Conjugal transfer and mobilization systems identified in silico on A. baumannii plasmids

| Plasmid | CDS protein identifier | Conjugal transfer or mobilization protein name and function | Source of homology | Amino acid identity (% best hit) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pACICU2 | P0058 | Type IV secretory pathway, VirD4, TraD component | Burkholderia cenocepacia | 40 |

| P0059 | TraI, relaxase-helicase for conjugative transfer | Pseudomonas sp. | 40 | |

| P0070 | TraA, conjugal transfer protein | Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans | 36 | |

| P0071 | TraL, putative membrane protein | Acidovorax sp. | 40 | |

| P0072 | TraE, conjugative transfer protein | Burkholderia cenocepacia | 30 | |

| P0074 | TraB, pilus assembly family protein | Acidovorax sp. | 33 | |

| P0075 | DsbC precursor protein, disulfide isomerase | Burkholderia thailandensis | 53 | |

| P0076 | TraV, membrane lipoprotein lipid attachment site | Acidovorax sp. | 44 | |

| P0077 | TraC, conjugative transfer protein | Burkholderia cenocepacia | 41 | |

| P0079 | TraW, conjugative transfer protein precursor | Burkholderia cenocepacia | 46 | |

| P0080 | TraU, conjugative transfer protein precursor | Burkholderia cenocepacia | 65 | |

| P0081 | Conjugative transfer protein | Burkholderia cenocepacia | 43 | |

| P0082 | TraN, conjugal transfer mating pair stabilization | Acidovorax sp. | 37 | |

| P0083 | TraF, conjugative transfer protein | Burkholderia cenocepacia | 48 | |

| P0085 | TraH, conjugative transfer protein | Burkholderia cenocepacia | 70 | |

| P0086 | TraG, domain containing protein | Burkholderia thailandensis | 32 | |

| P0088 | DNA-directed DNA polymerase UmuC | Acinetobacter sp. strain ATCC 27244 | 57 | |

| P0089 | DNA-directed DNA polymerase RumB | Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 17978 | 56 | |

| p1ABAYE | p1ABAYE0006 | Putative mobilization protein, MobS-like | Rhizobium leguminosarum | 40 |

| p1ABAYE0007 | TraA, putative mobilization protein, MobL-like | Sinorhizobium meliloti | 43 | |

| p1ABSDF | p1ABSDF0002 | Putative mobilization protein, MobS-like | Psychrobacter psychrophilus | 69 |

| p2ABSDF | p2ABSDF0026 | Putative mobilization protein, MobS-like | Polaromonas naphthalenivorans | 46 |

| p2ABSDF0028 | Putative mobilization protein, MobL-like | Agrobacterium tumefaciens | 45 | |

| p3ABSDF | p3ABSDF0010 | Putative mobilization protein, MobS-like | Psychrobacter psychrophilus | 69 |

| p3ABSDF0011 | Putative mobilization protein, MobL-like | Agrobacterium tumefaciens | 46 | |

| pMAC02 | pMAC_11 | Putative mobilization protein, MobA-like | Escherichia coli | 43 |

| pMMCU1, pMMD | pMMCU1p5 | Putative mobilization protein, MobA-like | Escherichia coli | 49 |

| pMMCU2 | pMMCU2_06 | Putative mobilization protein, MobA-like | Escherichia coli | 49 |

Even if plasmid pACICU2 was a unique plasmid endowed with a conjugative apparatus, plasmids p1ABAYE, p1ABSDF, p2ABSDF, p3ABSDF pMMCU1, pMMCU2, pMAC02, and pMMD showed some orthologs of the MobS-MobL or MobA mobilization proteins that are characteristic of a number of small plasmids that are mobilizable by self-transmissible plasmids. These proteins are required for recognizing and cleaving the nic site, directing the complex to the transferosome determined by the conjugative element (14).

The transconjugants obtained from the blaOXA-23-positive isolates harbored the aci6 replicase gene of pACICU2 that was confirmed to be located on the blaOXA-23-positive plasmid by Southern blot hybridization (data not shown). These results clearly indicate that plasmids similar to pACICU2 are present in those isolates and are able to self-conjugate. These pACICU2-related plasmids harbored the carbapenem resistance gene blaOXA-23, which, however, was absent from the original fully sequenced pACICU2 plasmid (19). Noteworthy is the fact that the aci6 replicase gene was also identified from 7 out of 13 blaOXA-58-positive isolates but did not correspond to the replicon associated with this resistance gene. These findings open a new and interesting scenario describing the transmission of resistance plasmids into A. baumannii, since the pACICU2-like plasmids seem to be widely diffused and are likely responsible for both blaOXA-58 plasmid mobilization and blaOXA-23 plasmid self-conjugation.

Conclusion.

The present study is the first to characterize the main features of the plasmids circulating among A. baumannii strains. Through an in silico analysis complemented by several experimental cloning experiments, 27 replicase genes have been identified. Primer sequences have been defined in order to characterize those 27 replicase genes, and a PCR-based methodology has been proposed to detect them in a convenient way. A multiplex approach has been set up by defining 19 distinct groups in 6 multiplexes, each of them grouping either three or four primer pairs that may allow faster and cheaper screening. Indeed, plasmid typing is a useful tool for studying their respective circulation and spread among members of the Acinetobacter genus and eventually among isolates of other genera. Through the epidemiological survey that has been conducted here, we exemplified what kind of approach that methodology can deserve. Here, we traced the diffusion of the carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinase genes blaOXA-23 and blaOXA-58, known to be the sources of resistance to carbapenems in A. baumannii worldwide. Interestingly, we showed that the current worldwide diffusion of the blaOXA-23 gene was mainly related to a single plasmid type and, conversely, that the diffusion of the blaOXA-58 gene was related to several unrelated plasmid types.

We aim to provide an easy, rapid, and reliable tool for investigating the plasmid epidemiology of A. baumannii. That kind of approach of performing plasmid typing will be useful and informative when studies focus on dissemination of specific markers only, such as a given antibiotic resistance gene, contributing to the better tracing of specific plasmids among a diversity of A. baumannii genetic backgrounds. This can be done in a way similar to that previously set up for the Enterobacteriaceae family that is now applied worldwide, and the corresponding so-called PBRT method is nowadays the main technique used to trace resistance plasmids among strains belonging to that family and improve knowledge of the evolution of drug resistance (4).

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Naas for providing several A. baumannii isolates, C. Giske for the gift of one A. baumannii isolate, and M. G. Smith for providing the ATCC 19798 strain.

This work was funded by grants from the Italian Ministero della Salute and French Ministère de l'Education Nationale et de la Recherche; by INSERM (U914), Université Paris XI, Paris, France; and mostly by the European Community (DRESP2, LSHM-CT-2003-503-335, and TROCAR, HEALTH-F3-2008-223031).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 July 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, M. D., K. Goglin, N. Molyneaux, K. M. Hujer, H. Lavender, J. J. Jamison, I. J. MacDonald, K. M. Martin, T. Russo, A. A. Campagnari, A. M. Hujer, R. A. Bonomo, and S. R. Gill. 2008. Comparative genome sequence analysis of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Bacteriol. 190:8053-8064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertini, A., L. Poirel, S. Bernabeu, D. Fortini, L. Villa, P. Nordmann, and A. Carattoli. 2007. Multicopy blaOXA-58 gene as a source of high-level resistance to carbapenems in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2324-2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bignell, C., and C. M. Thomas. 2001. The bacterial ParA-ParB partitioning proteins. J. Biotechnol. 91:1-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carattoli, A. 2009. Resistance plasmid families in Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2227-2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carattoli, A., A. Bertini, L. Villa, V. Falbo, K. L. Hopkins, and E. J. Threlfall. 2005. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J. Microbiol. Methods 63:219-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chattoraj, D. K. 2000. Control of plasmid DNA replication by iterons: no longer paradoxical. Mol. Microbiol. 37:467-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corvec, S., L. Poirel, T. Naas, H. Drugeon, and P. Nordmann. 2007. Genetics and expression of the carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinase gene blaOXA-23 in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1530-1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Couturier, M., F. Bex, P. L. Bergquist, and W. K. Maas. 1988. Identification and classification of bacterial plasmids. Microbiol. Rev. 52:375-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Andrea, M. M., T. Giani, S. D'Arezzo, A. Capone, N. Petrosillo, P. Visca, F. Luzzaro, and G. M. Rossolini. 2009. Characterization of pABVA01, a plasmid encoding the OXA-24 carbapenemase from Italian isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3528-3533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Datta, N., and R. W. Hedges. 1971. Compatibility groups among fi-R factors. Nature 234:222-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Datta, N. 1975. Epidemiology and classification of plasmids, p. 9-15. In D. Schlessinger (ed.), Microbiology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 12.Dorsey, C. W., A. P. Tomaras, and L. A. Actis. 2006. Sequence and organization of pMAC, an Acinetobacter baumannii plasmid harboring genes involved in organic peroxide resistance. Plasmid 56:112-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fondi, M., G. Bacci, M. Brilli, M. C. Papaleo, A. Mengoni, M. Vaneechoutte, L. Dijkshoorn, and R. Fani. 2010. Exploring the evolutionary dynamics of plasmids: the Acinetobacter pan-plasmidome. BMC Evol. Biol. 10:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frost, L. S., K. Ippen-Ihler, and R. A. Skurray. 1994. Analysis of the sequence and gene products of the transfer region of the F sex factor. J. Microbiol. Rev. 58:162-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcillán-Barcia, M. P., M. V. Francia, and F. de la Cruz. 2009. The diversity of conjugative relaxases and its application in plasmid classification. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33:657-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grady, R., and F. Hayes. 2003. Axe-Txe, a broad-spectrum proteic toxin-antitoxin system specified by a multidrug-resistant, clinical isolate of Enterococcus faecium. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1419-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helinski, D. R. 2004. Introduction to plasmids: a selective view of their history, p. 1-21. In B. E. Funnell and G. J. Philips (ed.), Plasmid biology. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 18.Higgins, P. G., L. Poirel, M. Lehmann, P. Nordmann, and H. Seifert. 2009. OXA-143, a novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D beta-lactamase in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:5035-5038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iacono, M., L. Villa, D. Fortini, R. Bordoni, F. Imperi, R. J. Bonnal, T. Sicheritz-Ponten, G. De Bellis, P. Visca, A. Cassone, and A. Carattoli. 2008. Whole-genome pyrosequencing of an epidemic multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strain belonging to the European clone II group. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2616-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim, Y., X. Wang, Q. Ma, X. S. Zhang, and T. K. Wood. 2009. Toxin-antitoxin systems in Escherichia coli influence biofilm formation through YjgK (TabA) and fimbriae. J. Bacteriol. 191:1258-1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawley, T., B. M. Wilkins, and L. S. Frost. 2004. Bacterial conjugation in Gram-negative bacteria, p. 203-226. In B. E. Funnell and G. J. Philips (ed.), Plasmid biology. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 22.Marchand, I., L. Damier-Piolle, P. Courvalin, and T. Lambert. 2004. Expression of the RND-type efflux pump AdeABC in Acinetobacter baumannii is regulated by the AdeRS two-component system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3298-3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marqué, S., L. Poirel, C. Héritier, S. Brisse, M. D. Blasco, R. Filip, G. Coman, T. Naas, and P. Nordmann. 2005. Regional occurrence of plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinase OXA-58 in Acinetobacter spp. in Europe. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4885-4888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merino, M., J. Acosta, M. Poza, F. Sanz, A. Beceiro, F. Chaves, and G. Bou. 2010. OXA-24 carbapenemase gene flanked by XerC/XerD-like recombination sites in different plasmids from different Acinetobacter species isolated during a nosocomial outbreak. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2724-2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mugnier, P. D., K. M. Bindayna, L. Poirel, and P. Nordmann. 2009. Diversity of plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolysing oxacillinases among carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from Kingdom of Bahrain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63:1071-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mugnier, P. D., L. Poirel, T. Naas, and P. Nordmann. 2010. Worldwide dissemination of the blaOXA-23 carbapenemase gene of Acinetobacter baumannii. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:35-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paulsson, J., and D. K. Chattoraj. 2006. Origin inactivation in bacterial DNA replication control. Mol. Microbiol. 61:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peleg, A. Y., H. Seifert, and D. L. Paterson. 2008. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21:538-582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poirel, L., T. Naas, and P. Nordmann. 2010. Diversity, epidemiology, and genetics of class D beta-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:24-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poirel, L., W. Mansour, O. Bouallegue, and P. Nordmann. 2008. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from Tunisia producing the OXA-58-like carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinase OXA-97. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1613-1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook, J. E., F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 32.Smith, M. G., T. A. Gianoulis, S. Pukatzki, J. J. Mekalanos, L. N. Ornston, M. Gerstein, and M. Snyder. 2007. New insights into Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenesis revealed by high-density pyrosequencing and transposon mutagenesis. Genes Dev. 21:601-614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sykora, P. 1992. Macroevolution of plasmids: a model for plasmid speciation. J. Theor. Biol. 159:53-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vallenet, D., P. Nordmann, V. Barbe, L. Poirel, S. Mangenot, E. Bataille, C. Dossat, S. Gas, A. Kreimeyer, P. Lenoble, S. Oztas, J. Poulain, B. Segurens, C. Robert, C. Abergel, J. M. Claverie, D. Raoult, C. Médigue, J. Weissenbach, and S. Cruveiller. 2008. Comparative analysis of Acinetobacters: three genomes for three lifestyles. PLoS One 19:e1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zarrilli, R., D. Vitale, A. Di Popolo, M. Bagattini, Z. Daoud, A. U. Khan, C. Afif, and M. Triassi. 2008. A plasmid-borne blaOXA-58 gene confers imipenem resistance to Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from a Lebanese hospital. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:4115-4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]