Abstract

Skeletal muscle weakness is a reported ailment in individuals working in commercial hog confinement facilities. To date, specific mechanisms responsible for this symptom remain undefined. The purpose of this study was to assess whether hog barn dust (HBD) contains components that are capable of binding to and modulating the activity of type 1 ryanodine receptor Ca2+-release channel (RyR1), a key regulator of skeletal muscle function. HBD collected from confinement facilities in Nebraska were extracted with chloroform, filtered, and rotary evaporated to dryness. Residues were resuspended in hexane-chloroform (20:1) and precipitates, referred to as HBDorg, were air-dried and studied further. In competition assays, HBDorg dose-dependently displaced [3H]ryanodine from binding sites on RyR1 with an IC50 of 1.5 ± 0.1 μg/ml (Ki = 0.4 ± 0.0 μg/ml). In single-channel assays using RyR1 reconstituted into a lipid bilayer, HBDorg exhibited three distinct dose-dependent effects: first it increased the open probability of RyR1 by increasing its gating frequency and dwell time in the open state, then it induced a state of reduced conductance (55% of maximum) that was more likely to occur and persist at positive holding potentials, and finally it irreversibly closed RyR1. In differentiated C2C12 myotubes, addition of HBD triggered a rise in intracellular Ca2+ that was blocked by pretreatment with ryanodine. Since persistent activation and/or closure of RyR1 results in skeletal muscle weakness, these new data suggest that HBD is responsible, at least in part, for the muscle ailment reported by hog confinement workers.

Keywords: muscle weakness, single channel, binding, C2C12 cells

pork consumption is increasing worldwide, and to keep up with demand, farmers are continuously expanding the size of their operations (26, 36). In developed and middle-income countries, hogs are housed in large confinement facilities, where they are fed a diet rich in grains and beans in preparation for market. The dust from the feed mixes with feces, urine, dander, bacteria, molds, and pungent volatile substances emanating from nearby manure pits to produce what is referred to as hog barn dust (HBD) (9, 11, 38). A growing body of literature indicates that HBD is an underlying cause for the increased incidence of health-related problems in workers in these facilities, including shortness of breath, wheezing, coughing, chest tightness, and asthma-like syndrome (10, 14, 34, 35, 37, 39, 40). Individuals living in proximity to these confinement facilities also reported increased confusion, depression, tension, and lack of vigor (31, 35).

The vast majority of studies conducted to date have focused on elucidating mechanisms underlying respiratory illnesses caused by HBD. Work by Larsson and coworkers found that short-term exposure (2–5 h) of healthy volunteers to HBD induces bronchial hyperresponsiveness and inflammation (21, 22). Long-term employees of confinement facilities also exhibit a reduction in 1-s forced expiratory volume (18, 32). Mice exposed to HBD were also found to have significant lung inflammation (28), and the latter likely results from activation of protein kinase C and the release inflammatory mediators, such as IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α (30, 33, 42). Aqueous extract of HBD (HBDaq) was also found to increase ciliary beating and adhesion of peripheral blood lymphocytes to bronchial epithelial cells (23, 41). HBDaq also activates toll-like receptor 2 present on lung epithelial cells, implicating the innate immune system as part of the lung response to HBD (1, 29).

In addition to the well-recognized and studied respiratory ailments, ≈25% of hog confinement facility workers also reported having skeletal muscle aches and fatigue (8, 17). While these ailments could be attributed to the physical work involved in these confinement facilities, the likelihood that HBD is a contributing factor has not been explored. Since organic compounds present in HBD could be absorbed via the skin, we reasoned that lipid-soluble (and even amphipathic) components of HBD could be binding to and disrupting the activity of proteins critical for skeletal muscle function. One of these proteins is the ryanodine receptor, the channel through which Ca2+ leaves the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) to enter the cytoplasm and evoke contraction (13). Type 1 ryanodine receptor (RyR1) is present in skeletal muscles and in the diaphragm, the major muscle regulating breathing (12, 19). Potentiating basal activity of RyR1 reduces SR Ca2+ load, and, as a result, the amplitude of evoked Ca2+ release is reduced, leading to muscle weakness (7). Similarly, if RyR1 is unable to activate or open in a timely manner, evoked Ca2+ release from the SR is compromised, also leading to muscle weakness. Thus the purpose of this study was to assess whether HBD contains compounds that are capable of binding to and modulating the activity of RyR1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

[3H]ryanodine (specific activity 87 Ci/mmol) was purchased from GE Life Sciences (Boston, MA). Phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylcholine, and phosphatidylethanolamine were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Dialysis membranes were obtained from Spectrum Laboratories (Rancho Dominguez, CA). All other reagents and solvents used were of the highest grade commercially available.

Extraction of HBD

HBD collected 1–2 m from the floor of hog confinement facilities in Nebraska were extracted three times with chloroform (CHCl3, 5 g in 70 ml for 1 h × 3 extractions). Pooled extracts from each sample were gravity filtered (Whatman no. 1 paper) and rotary evaporated to dryness (HBDCHCl3). HBDCHCl3 were then redissolved in hexane-CHCl3 (20:1, 40 ml), and the resultant precipitates were collected by gravity filtration, air-dried, and labeled HBDorg.

Composition of HBDorg

The composition of HBDorg was determined by spotting on silica gel thin layer plates and chromatographed using varying ratios of CHCl3-methanol (MeOH) with either triethylamine (TEA) or acetic acid (HAc). Compounds were visualized under 365-nm wavelength UV light. Plates were sprayed with 1% sulphuric acid and heated to assess for non-UV-active compounds.

Preparation of SR Vesicles

The University of Nebraska Medical Center, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved rabbits used for the study, and their short-term housing adhered to the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (27). Crude SR membrane vesicles (SR vesicles) were prepared from back and hindleg fast-twitch muscles, as described previously (3). Briefly, after induction of anesthesia with methohexital sodium (150 mg/kg) via an ear vein, fast-twitch muscles were removed, homogenized (speed setting 4.5, ProScientific, Oxford, CT), in isolation buffer [0.3 M sucrose, 10 mM imidazole·HCl, 230 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1.1 μM leupeptin, pH 7.4], and centrifuged at 7,500 gav (average g) for 20 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in fresh isolation buffer, homogenized for 1-s time at speed setting 5.5, and centrifuged at 11,000 gav for 20 min. The supernatant was then filtered through cheesecloth, and SR vesicles were obtained by sedimentation at 85,000 gav (Beckman Ultra Centrifuge, Ti45 rotor) for 30 min.

Preparation of RyR1 Reconstituted into Proteoliposomes

Proteoliposomes containing RyR1 were prepared as described earlier by Lai and coworkers (20) with some modifications. SR vesicles were fractionated by placing on top a discontinuous sucrose gradient (26 ml each, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2, and 1.5 M) and centrifuging at 110,000 gav for 2 h (Ti45 rotor). The vesicles at the interface between 1.2 and 1.5 M sucrose were collected, resuspended in fresh isolation buffer, and harvested by centrifugation at 110,000 gav for 2 h. The resultant pellet enriched in junctional SR vesicles was then solubilized in buffer (19 ml) containing 1.0 M NaCl, 0.05 mM EGTA, 0.35 mM Ca2+, 5 mM AMP, 20 mM Na/PIPES, pH 7.4, 0.3 mM Pefabloc, 0.03 mM leupeptin, 0.9 mM DTT, 1.5% CHAPS, and 5 mg/ml phosphatidylcholine for 10 min at room temperature (24°C), followed by 1 h embedded in ice. CHAPS-insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 26,163 gav (Beckman Ultra Centrifuge, Ti75 rotor) for 30 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was further fractionated on a linear sucrose gradient (7–15% sucrose, 34 ml per tube, 6 tubes, 3 ml of solubilized protein per tube) by centrifugation at 89,454 gav (Beckman Ultra Centrifuge, SW28 rotor) for 17 h at 4°C. [3H]ryanodine (3.3 nM) was added to one of the tubes to serve as a guide for RyR1 purification. After centrifugation, 2.0-ml aliquots from the [3H]ryanodine-labeled tube were collected from the bottom of the tube upwards and counted to determine the location of [3H]ryanodine and RyR1. Twenty-microliter volumes from each aliquot were mixed with gel dissociation medium and electrophoresed on 4–15% linear gradient Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gel at 150 V for 180 min and then silver stained according to manufacturer's protocol (BioRad, Burlingame, CA). RyR1-containing fractions from the five unlabeled tubes were pooled and dialyzed at 4°C for 44 h in buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM Na/PIPES, pH 7.4, 0.1 mM DTT, and 0.4 mM PMSF with three buffer changes at 2, 6, and 15 h. After dialysis, proteoliposomes containing RyR1 were diluted 1:1 in buffer containing 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM Na/PIPES, pH 7.4, 0.1 mM DTT, and 0.4 mM PMSF and centrifuged at 163,520 gav (Ti75 rotor) for 2 h. The pellet was then resuspended in 0.1 M NaCl, 10 mM Na/PIPES, pH 7.4, and 0.3 M sucrose; aliquoted (100 μl); quick-frozen in liquid nitrogen; and stored frozen in the vapor phase of liquid nitrogen until use.

Competition Binding Assays

Competition binding assays were used to assess the ability of HBDorg to bind to RyR1. This assay was also used to calculate IC50 and Ki of HBDorg, as well as general information on the location(s) of the binding site(s) for HBDorg on RyR1.

Binding of HBDorg to RyR1.

SR vesicles (0.1 mg/ml) were incubated in binding buffer consisting of 500 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris·HCl, 0.4 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4, 6.7 nM [3H]ryanodine with HBDorg (20, 2.0, and 0.2 μg/ml) for 2 h at 37°C. HBDCHCl3 (220, 110, and 55 μg/ml), ryanodine (1 μM) and the solvent [CHCl3/MeOH/dimethylformamide (DMF); 2:1:1] used to dissolve HBDCHCl3 and HBDorg were also used. At the end of the incubation, samples were rapidly filtered through GF/C filters using a cell harvester (Brandel, Gaithersburg, MD) and washed three times with 3 ml of ice-cold binding buffer, and the amount of [3H]ryanodine bound to the filters was determined by liquid scintillation counting (16).

Determination of IC50 and Ki of HBDorg.

For this, 12 concentrations of HBDorg, ranging from 0.2 to 20 μg/ml were used in competition assays. For comparison, the displacement-binding curve for the RyR1-selective ligand ryanodine was run concurrently in each assay. Displacement data were fitted using nonlinear regression to a one- and a two-site competition model given by equations as described by Motulsky and Christopoulos (25) respectively.

| (1) |

| (2) |

where Y is specific binding, X is the logarithm of the amount of the unlabeled ligand, and log IC50 is the competitor concentration that displaces one-half of the specifically bound [3H]ryanodine. Goodness of fit was evaluated by F-test.

Equilibrium inhibition constant (Ki) for HBDorg was calculated using the Cheng-Prusoff relationship (6) given by equation 3

| (3) |

where L is the concentration of [3H]ryanodine used (6.7 nM) and KL is the equilibrium dissociation constant of [3H]ryanodine (2.4 nM for RyR1) (4).

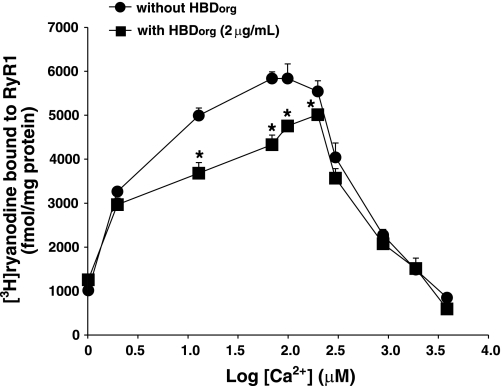

Ca2+-dependency of HBDorg actions.

Ca2+ is routinely used in the binding buffer to activate or open RyR1, and, under these conditions, the amount of [3H]ryanodine bound to RyR1 is substantially increased. In the absence of Ca2+ or in high Ca2+ (>900 μM), RyR1 becomes deactivated or closed, and the amount of [3H]ryanodine bound to RyR1 decreases precipitously (2). We, therefore, reasoned that competition assays employing a fixed amount of HBDorg in the presence of varying amounts of Ca2+ could provide insights into whether the actions of HBDorg are dependent on the open or closed conformation of RyR1. SR membrane vesicles (0.1 mg/ml) were incubated in binding buffer containing 2.0 μg/ml HBDorg and increasing amounts of Ca2+ (2–3,900 μM) for 2 h at 37°C. After incubation, vesicles were filtered and washed, and the amount of [3H]ryanodine bound was determined using liquid scintillation counting.

Single-channel Measurement and Analyses

Single-channel analyses were performed as described earlier (5). Briefly, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine, and phosphatidylcholine in a ratio of 5:3:2 (35 mg/ml of lipid) in n-decane were painted across a 200-μm-diameter hole of the bilayer cup. Purified RyR1 in proteoliposomes was then fused to the bilayer. The side of the bilayer to which the proteoliposomes were added was designated the cis side. The trans side was defined as ground. Single channels were recorded in symmetric KCl buffer solution (0.25 mM KCl, 20 mM K/HEPES, pH 7.4) with 3.3 μM Ca2+ or as specified. In this study, free calcium concentrations were titrated against EGTA. HBDorg was made up in CHCl3/MeOH/DMF (2:1:1) at concentrations up to 500 times higher than that anticipated for use in the bilayer bath (≤1% solvent in bath). All experiments were carried out at room temperature (23–25°C), and HBDorg was added only to the cis chamber. Electrical signals were filtered at 2 kHz, digitized at 10 kHz, and analyzed as described earlier (5). Normal gating mode is defined to include periods of rapid channel transitions between the closed and full open states, and subconductance mode is defined as periods in which the channel exhibits a persistently reduced conductance. The magnitude of the subconductance state was calculated by dividing the amplitude of the subconductance induced by the HBDorg by the conductance of the channel before HBDorg (full conductance). Amplitudes were monitored by manual positioning of cursors at each level, corresponding to closed, subconductance, and open-conductance states. Data acquisition and analyses were performed using commercially available instruments and software (Axopatch 1D, Digidata 1200A or 1322A and pClamp 10.0, Axon Instruments, Burlingame, CA). Some data analyses were also carried out using Sigma Plot 10.0 (Stystat Software, Chicago, IL).

Cell Culture and Ca2+ Transients

Undifferentiated C2C12 cells (mouse myoblast cell line), obtained as a gift from Dr. Gregory S. Taylor (Department of Biochemistry, UNMC), were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 1.8 mM CaCl2 (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and antibiotics (100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 μg/ml gentamicin, pH 7.3) to 70–80% confluency. Cells were then subcultured and plated onto laminin-coated glass-bottom chambers and placed in an incubator for 24 h with 5% CO2/95% air at 37°C. After this time, the media was changed, fetal bovine serum was reduced to 2%, and cells were allowed to differentiate for 96 h into myotubes. Differentiated myotubes in DMEM (containing 1.8 mM Ca2+) were then loaded with fluo 3-AM (5 μM) for 30 min at 37°C, washed, and placed on the stage of a laser confocal microscope (Zeiss Confocal LSM 410 confocal microscope equipped with an Argon-Krypton Laser, 25 mW argon laser, 2% intensity, Thornwood, NJ). HBDorg in dimethylsulfoxide was then manually added to a corner of the glass chamber and allowed to diffuse into the cell medium, and Ca2+ transients (ΔF) were recorded. The final dimethylsulfoxide in the chamber was <5%. In some experiments, after loading fluo 3 and washing, 500 mM EGTA were added to DMEM media to chelate extracellular Ca2+. In other experiments, differentiated C2C12 cells were incubated with 50 μM ryanodine 20 min at 37°C before loading with fluo 3-AM. Cells were then challenged with HBDorg, and Ca2+ transients were recorded. Fluo 3 was excited by light at 488 nm, and fluorescence was measured at wavelengths of >515 nm. Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Seattle, WA) and Sigma Plot (Systat, Chicago, IL).

Statistical Analyses

Data shown are means ± SE. Differences among concentrations were analyzed using analysis of variance, followed by the Bonferroni (post hoc) test using Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Preparation of Chloroform Extract of HBD

Chloroform extraction of HBD (HBDCHCL3) afforded a pale yellow paste (≈5% yield) that exhibited greenish-blue fluorescence under 365-nm wavelength light. At 305 nm, the greenish-blue fluorescence was less intense. When sprayed with 1% sulfuric acid and heated, the major compounds overlaid with the UV-active compounds. Sulfuric acid also revealed low levels of other non-UV active compounds. When redissolved in hexane-CHCl3 (20:1), a brownish precipitate (HBDorg, 40% yield) was obtained that fluoresced under UV light. The discarded hexane-CHCl3 (20:1) fraction contained very weak UV-active spots that did not react with sulfuric acid.

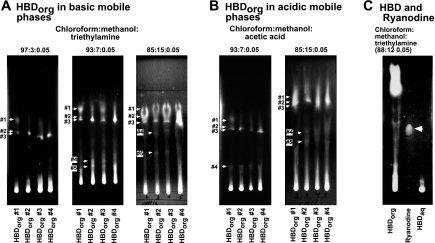

Chromatographic Characterization of HBDorg

Basic (TEA) and acidic (HAc) mobile phases of increasing polarities were employed to gain insights into the composition of HBD. When spotted on a thin-layer chromatographic plate and developed using a mobile phase consisting of CHCl3/MeOH/TEA (97:3:0.05), all four HBDorg extracts contained three major compounds that migrated with Rf 0.65, (#1), 0.52 (#2), 0.52 (#3; Fig. 1A, left, arrows). Compounds 2 and 3 were better resolved in sample 1. In this solvent system, all four HBDorg samples exhibited streaking near the origin of the plate. Increasing the polarity of the basic mobile phase to 7% methanol resulted in the appearance of two additional compounds with Rf values of 0.2 (#4) and 0.15 (#5). Increasing the polarity of the mobile phase to 15% methanol did not reveal any additional compounds. However, the resolution of compounds 4 and 5 was enhanced. In all three basic mobile phases of increasing polarities, bright streaks were seen at the origin, suggesting that HBDorg also contains very polar, nonbasic compounds.

Fig. 1.

Chromatographic mobilities of hog barn dust (HBD) chloroform extract (HBDCHCl3) precipitates (HBDorg). A and B: 5 μl from 5 mg/ml solutions of HBDorg spotted on a thin-layer silica gel plate and developed for 45 min in solvents containing mixtures of CHCl3/MEOH with either triethylamine (A) or acetic acid (B). The plates were air-dried, visualized under 365-nm wavelength light, and photographed. Rf values were determined by measuring the distance the compound moved from the origin relative to the distance moved by the solvent. C: 10 μl from 5 mg/ml solution of HBDorg and 10 μl from 1 g/10 ml solution of HBD aqueous extract (HBDaq) spotted on a thin-layer silica gel plate alongside ryanodine (10 μl from 10 mg/ml).

Replacing TEA with HAc in the mobile phase also revealed the presence of five major compounds in HBDorg (Fig. 1B). Bright streaks were also seen at origin in acid mobile phases. At this time, it is not clear whether the compounds that separated with the basic mobile phases are the same as those that separated with the acidic mobile phases.

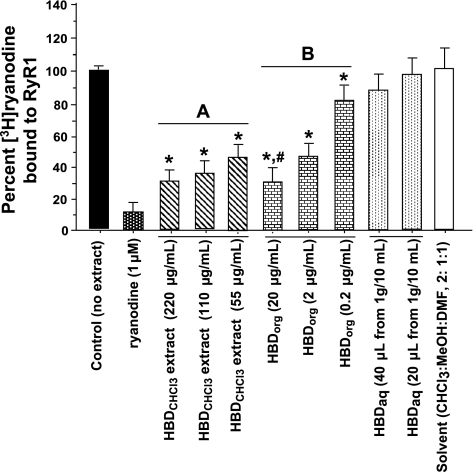

Assessing the Ability of HBDorg to Bind to RyR1

HBDorg dose-dependently displaced [3H]ryanodine from RyR1 and, as expected, was ≈10× more potent than HBDCHCl3 (Fig. 2). Ryanodine (1 μM) displaced >90% of [3H]ryanodine from RyR1. CHCl3/MeOH/DMF (2:1:1) used to dissolved HBDCHCl3 and HBDorg (4%) had minimal effect on the binding of [3H]ryanodine to RyR1. HBDaq did not significantly affect the binding of [3H]ryanodine RyR1 at the concentrations used (20 and 40 μl from a 1 g/10 ml extract in 400 μl of binding buffer).

Fig. 2.

Screening HBD for type 1 ryanodine receptor Ca2+-release channel (RyR1) activity. [3H]ryanodine competition assays were conducted with various amounts of HBDCHCl3, HBDorg, HBDaq, and solvent controls. For this, sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) vesicles (0.1 mg/ml) were incubated in binding buffer consisting of 500 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris·HCl, 0.3 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4, 6.7 nM [3H]ryanodine with HBDCHCl3 (220, 110, and 55 μg/ml), HBDorg (20, 2.0, and 0.2 μg/ml), ryanodine (1 μM), and the solvent [CHCl3/MeOH/dimethylformamide (DMF); 2:1:1], for 2 h at 37°C. At the end of the incubation, samples were rapidly filtered through GF/C filters using a cell harvester (Brandel, Gaithersburg, MD) and washed three times with 3 ml of ice-cold binding buffer, and the amount of [3H]ryanodine bound to the filters was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Data for each compound represent means ± SE from four experiments. A Dose response for chloroform extract of HBD. B Dose response for organic extract of HBD. *Significantly different from control (P < 0.05). #Significantly less than that of 2 and 0.2 μg/ml HBDorg (P < 0.05).

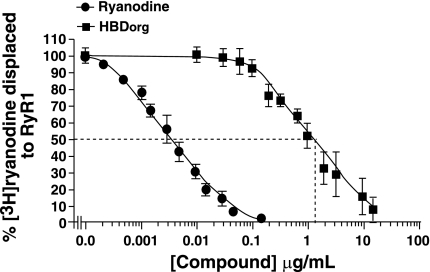

The affinity of HBDorg for RyR1 was then determined using a wide concentration range of HBDorg in displacement assays. As shown in Fig. 3, HBDorg displaced [3H]ryanodine from RyR1 in a concentration-dependent manner. The experimental data fitted well to a one-site binding model (r2 = 0.95, F = 0.92), affording an IC50 value of 1.5 ± 0.10 μg/ml. The data also fitted well to a two-site model (r2 = 0.95, F = 0.92). Since displacement occurred over two log units, the less complicated single-site model was used for fitting data (25). For comparison, the displacement isotherm of ryanodine is shown in the solid circles, exhibiting an IC50 of 3.8 ± 0.2 ng/ml (IC50 = 7.7 ± 0.4 nM, given molecular mass of 493 Da). Using Eq. 3 with L = 13.59 ng/ml (6.7 nM [3H]ryanodine) and KL of ryanodine of 4.8 ng/ml (2.4 nM), the Ki for HBDorg binding to RyR1 was calculated to be 0.4 μg/ml. The binding isotherms of RyR1 and HBDorg were also parallel, suggesting that both ryanodine and the active compound(s) of HBDorg are binding to the same site(s) on RyR1.

Fig. 3.

Determining the affinity of HBDorg for RyR1. Displacement [3H]ryanodine binding assays were used to determine the affinity of HBDorg for RyR1. For this, SR vesicles (0.1 mg/ml) were incubated in binding buffer consisting of 500 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris·HCl, 0.3 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4, and 6.7 nM [3H]ryanodine with 12 concentrations of HBDorg (0.007–15.75 μg/ml) for 2 h at 37°C. At the end of the incubation, samples were rapidly filtered through GF/C filters using a cell harvester (Brandel) and washed three times with 3 ml of ice-cold binding buffer, and the amount of [3H]ryanodine bound to the filters was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Data for each compound represent means ± SE from four experiments. For comparison, ryanodine was also used in this assay.

To gain insight into whether the effect of HBDorg is dependent on the open or closed conformation of RyR1, displacement assays were conducted with varying Ca2+ concentrations. As shown in Fig. 4, in the absence of Ca2+ or at high Ca2+ (≥900 μM), HBDorg was to unable displace [3H]ryanodine from RyR1. However, HBDorg competed with [3H]ryanodine at all concentrations of Ca2+ that activated or opened RyR1 (2–300 μM).

Fig. 4.

Determining the Ca2+ dependency of HBDorg effect on RyR1. For this, SR vesicles (0.1 mg/ml) were incubated in binding buffer consisting of 500 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris·HCl, 0.1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4, 6.7 nM [3H]ryanodine, with 2.0 μg/ml HBDorg and increasing amounts of Ca2+ (2–3,900 μM) for 2 h at 37°C. At the end of the incubation, samples were rapidly filtered through GF/C filters using a cell harvester (Brandel) and washed three times with 3 ml of ice-cold binding buffer, and the amount of [3H]ryanodine bound to the filters was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Data for each compound represent means ± SE from four experiments. *Significantly different from [3H]ryanodine bound in absence of HBDorg (P < 0.05).

Effects of HBDorg on Single RyR1 Channels

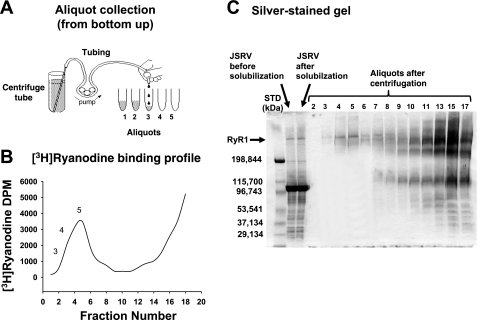

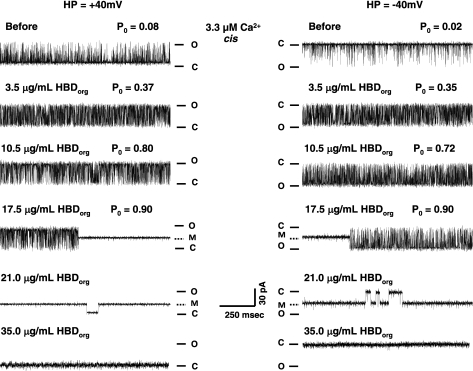

Figure 5 shows the elution profile and a silver-stained gel of aliquots collected following solubilization and centrifugation of junctional SR membranes. Fractions 3, 4, and 5 were collected, dialyzed, and used in single-channel assays, to gain additional insight into mechanisms by which HBDorg alters the activity of RyR1. Three distinct effects were observed when HBDorg was added to the cis chamber of the bilayer cup. At a concentration of 3.5 μg/ml, HBDorg increased the probability of RyR1 opening (Po) from 0.08 ± 0.01 to 0.37 ± 0.05 at +40 mV, and from 0.02 ± 0.01 to 0.35 ± 0.08 at −40 mV within 3 min after addition (Fig. 6, left, 1st and 2nd panels). This increase in Po resulted from increases in both the frequency of transitions from the closed to the full open state (number of events increased from 556 ± 48 to 841 ± 154/s, P < 0.05) and dwell time in the open state (from 0.39 ± 0.11 to 0.73 ± 0.13 ms, P < 0.05). Dwell time in the closed state also decreased from 4.2 ± 0.8 to 1.2 ± 0.5 ms (P < 0.05). The increase in Po was seen at both +40 mV and −40 mV holding potentials. The solvent used to dissolve HBDorg had no significant effect on the activity of RyR1 (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Purification of RyR1 using linear sucrose gradient centrifugation. Sucrose gradient (linear) centrifugation was used to purify RyR1. For this, junctional membrane vesicles were solubilized using CHAPS and then loaded on top of a linear sucrose gradient (7–15% sucrose, 34 ml per tube, ×6 tubes) and centrifuged at 89,454 gav (average g) for 17 h at 4°C. [3H]ryanodine (3.3 nM) was added to one of the tubes to serve as a guide for RyR1 purification. After centrifugation, 2.0-ml aliquots from the [3H]ryanodine-labeled tube were collected from the bottom of the tube upwards (A) and counted to determine the location of [3H]ryanodine and RyR1 (B). C: 20-μl volumes from each aliquot were mixed with gel dissociation medium also electrophoresed on 4–15% linear gradient Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gel at 150 V for 180 min and then silver stained, according to manufacturer's protocol (BioRad, Burlingame CA). JSRV, junctional SR vesicles; STD, standard.

Fig. 6.

Effects of HBDorg on single RyR1. Single-channel currents were recorded at +40 mV (left, upward deflections) and −40 mV (right, downward deflections) in symmetric KCl buffer solution (0.25 mM KCl, 20 mM K/HEPES, pH 7.4), as described in the text. The top right and left panels show representative recordings of RyR1 in the presence of 3.3 μM cytosolic Ca2+ before addition of HBDorg to the cis chamber. The panels below thereafter represent the effect of varying concentrations of HBDorg. The second and third panels from the top show increases in open probability (Po), the fourth panel shows the induction of a subconductance state, and the fifth and sixth panels show induction of the closed state of the channel. Data shown are representative of six separate channels. HP, holding potential; O, open; C, closed; M, modified.

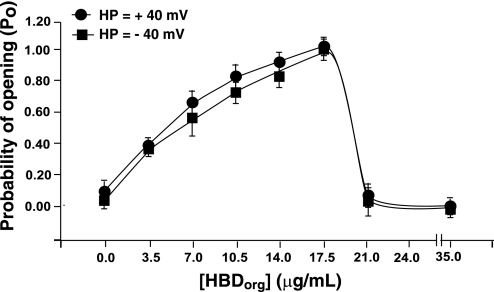

Tripling the cis concentration of HBDorg to 10.5 μg/ml further increased the Po of RyR1 at both positive and negative holding potentials. This increase in Po also resulted from increases both in its gating frequency of RyR1 (number of events increased to 748 ± 201, P < 0.05) and its dwell time in the open state (1.8 ± 0.9 ms). Dwell time in the closed state also decreased to 0.6 ± 0.2 ms. Increasing the amount of HBDorg in the cis chamber of the bilayer bath to 17.5 μg/ml induced a state of reduced conductance (subconductance) with current amplitude of 55 ± 4% of the fully opened state (391 ± 45 vs. 710 ± 90 pS, P < 0.05). Induction of this subconductance state (with Po = 1) was more likely to occur and persisted for longer times at +40 than at −40 mV. In fact, the time to modification and the probability of occurrence of the subconductance state were about five times more likely at positive holding potentials than at negative holding potentials. At positive holding potentials and with 17.5 μg/ml HBDorg, no transitions were observed from the subconductance state to either the full open or closed states (Fig. 6, left, 4th panel). At −40 mV, the subconductance state was noticeably noisier than at positive holding potentials, and the channel transitioned to the fully open state with high Po. Increasing the concentration of HBDorg even further to 21.5 μg/ml resulted in the channel predominantly residing in a subconductance state at both positive and negative holding potentials, with occasional transitions to the closed state. Higher concentrations (≥35.0 μg/ml) of HBDorg resulted in irreversible channel closure. Figure 7 shows the pooled data of the effects of HBDorg on the Po of RyR1.

Fig. 7.

Effects of HBDorg on the Po of RyR1. The currents of single RyR1 incorporated into lipid bilayers were recorded at +40 mV and −40 mV (in symmetric KCl buffer), and Po of the channel (transition from closed to full open state) in the presence of varying amounts of HBDCHCl3 in the cis chamber were plotted. Data shown are means ± SE from six channels.

The effects of HBDorg on gating and conductance of RyR1 are reminiscent of that seen with the plant alkaloid ryanodine. Accordingly, we assessed whether ryanodine might be present in HBDorg. When spotted on a silica gel thin-layer chromatographic plate and developed using a mobile phase consisting of CHCl3/MeOH/TEA (88:12:0.05), neither HBDorg nor HBDaq contained any compound with a chromatographic mobility (Rf) similar to that of ryanodine (Fig. 1C, arrow, Rf for ryanodine = 0.39).

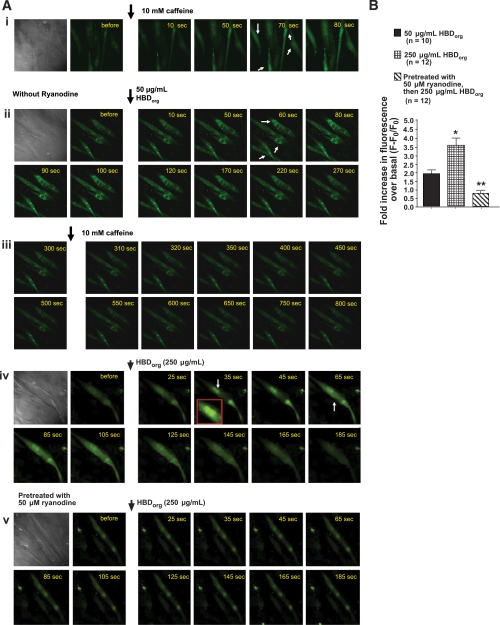

HBDorg Triggers Ca2+ Release From Differentiated C2C12 Myotubes

Binding and single-channel studies indicate that HBDorg contains compound(s) that binds to and modulates the activity of RyR1. We then tested whether HBDorg can also modulate the activity of RyR1 in intact, differentiated C2C12 myotubes (skeletal muscle cells). When added to fluo 3-loaded C2C12 myotubes, HBDorg (50 μg/ml) increased cytoplasmic Ca2+ (Fig. 8A, ii). The peak rise in Ca2+ (ΔF) was 1.9 ± 0.2-fold over basal and occurred ≈80 s after addition of HBDorg. The transient decayed to basal 300 s after the addition of HBD. While caffeine (10 mM) was able to trigger Ca2+ release in differentiated C2C12 cells (Fig. 8A, i), it was unable to do so after addition of 50 μg/ml HBDorg (Fig. 8A, iii). Addition of 250 μg/ml HBDorg induced a more robust increase in intracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 8A, iv). The peak rise in fluorescence (ΔF) was 3.6 ± 0.2-fold over basal and occurred ≈80 s after the addition of HBDorg. Treating differentiated C2C12 cells with 50 μM ryanodine for 20 min to block intracellular RyR1 blunted the increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ induced by HBDorg (Fig. 8, Av and B). Using EGTA to chelate extracellular Ca2+ minimally impact the ability of HBDorg to trigger Ca2+ release from C2C12 cells, indicating that HBDorg is inducing intracellular Ca2+ release (data not shown).

Fig. 8.

Ability of HBDorg to trigger Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Differentiated C2C12 myotubes grown on laminin-coated glass bottom chambers were loaded with fluo 3-AM (5 μM) for 30 min at 37°C, washed, and placed on the stage of a laser confocal microscope (Zeiss Confocal LSM 410 confocal microscope equipped with an Argon-Krypton Laser, 25 mW argon laser, 2% intensity, Thornwood, NJ). A: caffeine (10 mM; i) and HBDorg (50 μg/ml; ii, and 250 μg/ml; iv) were added to the chambers, and Ca2+ transients recorded. iii: Three minutes after addition of 50 μg/ml HBDorg and Ca2+ transient generation, caffeine (10 mM) was added. v: In separate experiments, differentiated C2C12 cells were incubated with 50 μM ryanodine 20 min at 37°C before loading with fluo 3-AM and exposure to 250 μg/ml HBDorg. B: fold increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ following addition of HBDorg (50 and 250 μg/ml, with and without ryanodine). Values are means ± SE of peak Ca2+ release for >10 cells from 4 separate experiments. *Significantly different from 50 μg/ml HBDorg (P < 0.05). **Significantly different from 50 μg/ml HBDorg and 250 μg/ml HBDorg (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Hog production is a major agricultural industry in the United States, Europe, and several middle-income countries (36). While the economic impact is clear, environmental and health-related issues resulting from this industry are experiencing an avalanche of public discussion. Leading the debate is the issue of the effect of confinement dust on the health and well-being of workers and individuals living in communities surrounding these facilities. It is becoming clearer that inhalation of HBD contributes to the increased incidence of respiratory ailments, including shortness of breath, wheezing, coughing, and chest tightness, among confinement facility workers (10, 14, 34, 37, 39, 40). However, what is not clear whether HBD is also contributing to skeletal muscle weakness and fatigue, and, if it does, what are the mechanism(s) (8, 17)?

The principal finding of the present study is that chloroform extracts of HBD collected from confinement facilities across Nebraska bind to and modulate the activity of RyR1. Using displacement assays, we found that all four samples of HBDorg exhibited high affinities for RyR1 (Ki = 0.39 μg/ml) and that the binding of HBDorg to RyR1 is preferred when the channel is in an activated or opened state. The latter is very important, as it suggests that active or working muscles are more prone to the effects of HBD than nonactive muscles. Using black lipid bilayers, we also found that HBDorg exhibited three distinct, dose-dependent effects on binding to RyR1. At low microgram amounts, HBDorg increased the Po of RyR1 by mechanisms that involved increasing both the gating of RyR1 and its dwell time in the open state. At higher concentrations of HBDorg, RyR1 transitioned into a state of reduced conductance (55% of full open) with a Po of 1. In the presence of even more HBDorg, RyR1 irreversibly closed. Irreversible closure of RyR1 could be a result of slow dissociation of HBDorg from RyR1. Thus HBDorg is a potent modulator of RyR1.

Parallel findings were also observed in skeletal muscle myotubes. When added to the culture chamber, HBDorg increased Ca2+ in differentiated C2C12 myotubes in a dose-dependent manner. The rise in intracellular Ca2+ persisted for ∼1 min and then decayed to near or even below basal. Removal of Ca2+ from the medium minimally impacted the ability of HBDorg to increase intracellular Ca2+, indicating that the Ca2+ rise is originating from inside and not from outside the cell. Pretreating differentiated C2C12 cells with ryanodine to close intracellular RyR1 blunted the ability of HBDorg, suggesting that the initial intracellular Ca2+ rise occurs via activation of RyR1. The inability of caffeine to trigger Ca2+ release post-HBDorg treatment is also consistent with the initial intracellular Ca2+ rise occurring via activation of RyR1. From single-channel studies, the rise in intracellular Ca2+ in C2C12 cells is likely the result of HBDorg increasing the gating frequency and inducing a state of reduced conductance of RyR1. The lower basal cytoplasmic Ca2+ post-HBDorg treatment and the inability of caffeine to trigger Ca2+ release post-HBDorg suggest that HBDorg is shutting RyR1, consistent with single-channel data.

Increasing the basal activity of RyR1, as is the case when its Po is increased or a subconductance state is induced, would result in leakage of Ca2+ from the SR. As a result, the amount of Ca2+ available for contraction following depolarization would be compromised. Inactivating or closing RyR1, as would be the case with higher amounts of HBDorg, would result in excitation-contraction uncoupling, as little or no Ca2+ would be released from the SR via an inactivated RyR1. Since effective skeletal muscle contraction requires the coordinated release of sufficient amounts of Ca2+ from the SR, these data provide, for the first time, a physiological rationale for the muscle weakness reported by hog confinement facility workers (8, 17). Since RyR1 is also a key Ca2+ release channel involved in diaphragm contraction (12, 19), the data from the present study also suggest that HBD could be compromising breathing, by another mechanism, i.e., impairment in diaphragm function. However, more work is needed to establish this. It would also be of interest to assess whether HBDorg is capable of modulating the activity of other cells that expresses RyR1 (13, 15).

HBDorg could enter into the circulation and access RyR1 via two major routes: absorption though the skin, and inhalation through the lung. While most companies require individuals working in concentrated animal feeding operations to wear protective coverings over hair and clothing and to use a respirator (24), it is conceivable that necks and faces are less likely to be protected, and these areas could serve as absorption sites for HBD components. Sweat produced during the course of work could also serve to increase the amount of HBD accumulated in these areas. The acidity of sweat is not likely to affect the components of HBD, as we did not observe any degradation in our chromatographic studies (Fig. 1). To what extent workers comply with the clothing policy is not clear. However, it is conceivable that thick or low porosity clothing worn during hot summer days could be a hindrance for workers.

Individuals working in concentrated animal feeding operations are also required to wear respirators. However, confinement facility workers find respirators to be a nuisance as they can become easily clogged (24). If these masks are not personalized, as is likely the case, leakage will occur, and inhalation could also serve to increase circulating concentrations of HBD components. However, the tolerance to inhalation is likely to be less than that which can be attached to the skin.

A surprising finding of the present study is that HBDorg exhibits actions on RyR1 similar to those seen with the plant alkaloid ryanodine (5, 13, 20). Specifically, at low concentrations, it activated or increased the Po of RyR1, and at higher concentrations it closed RyR1. However, none of the HBD samples analyzed to date contained any compounds that migrated with a chromatographic mobility similar to that of ryanodine (or its congener 9,21-didehydroryanodine) (Fig. 1C). These data are exciting, as they indicate another source for ligands that can modulate the activity of RyR1. Which component of HBDorg produces ryanodine-like actions is not known at this time. Because of this unexpected finding, it would be of great interest to assess whether HBDorg can also modulate the activities of the other isoforms of RyR, namely type 2 ryanodine receptor (RyR2, predominant in heart) and type 3 ryanodine receptor (RyR3, predominant in diaphragm and brain).

It should be mentioned that, during preliminary fractionation of HBDorg, a white crystalline solid was isolated and identified as lauric acid by 1H- and 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (data not shown). In between batches of animals, confinement facilities are hosed and cleaned with commercial detergents, and it is likely that residual detergent molecules are serving as nuclei to attract HBD particles. In preliminary studies, up to 10 μg/ml lauric acid had no effect on the ability of [3H]ryanodine to bind to RyR1 (data not shown).

In conclusion, we have shown 1) using rabbit skeletal muscle membrane vesicles that HBDorg displaces [3H]ryanodine from RyR1; 2) using purified RyR1 reconstituted into lipid bilayers that HBDorg modulates the gating and conductance of RyR1; and 3) using differentiated C2C12 that HBDorg triggers release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores via activation of RyR1. These new data provides a mechanistic rationale for the skeletal muscle weakness reported by hog confinement facility workers. They also raise several intriguing questions. Since RyR1 is present in many other cell types (the diaphragm, monocytes, B-cells, T-cells, dendritic cells, neurons, etc.), is modulation of RyR1 central to the reported effects of HBD? Also, since the actions of HBD on RyR1 are similar to that of the plant alkaloid ryanodine, could HBD also interact with and alter the activities of the other ryanodine receptor isoforms, i.e., RyR2 and RyR3? If the latter holds, then HBD could be the underlying cause for additional ailments. Identify the components of HBD that bind to and modulate the activity of RyR1 is, therefore, of utmost importance.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL085061 to K. R. Bidasee and OH008539 to D. J. Romberger).

REFERENCES

- 1. Bailey KL, Poole JA, Mathisen TL, Wyatt TA, Von Essen SG, Romberger DJ. Toll-like receptor 2 is upregulated by hog confinement dust in an IL-6-dependent manner in the airway epithelium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L1049–L1054, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Besch HR, Shao CH, Bidasee KR. Ryanoids, receptor affinity and RyR channel conductance. In: Ryanodine Receptors, Why the Discordance?: Structure, Function, and Dysfunction in Clinical Disease, edited by Wehrens X, Marks AR. New York: Springer, 2005, p. 179–189 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bidasee KR, Besch HR., Jr Structure-function relationships among ryanodine derivatives. Pyridyl ryanodine definitively separates activation potency from high affinity. J Biol Chem 273: 12176–12186, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bidasee KR, Maxwell A, Reynolds WF, Patel V, Besch HR., Jr Tectoridins modulate skeletal and cardiac muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium-release channels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 293: 1074–1083, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bidasee KR, Xu L, Meissner G, Besch HR., Jr Diketopyridylryanodine has three concentration-dependent effects on the cardiac calcium-release channel/ryanodine receptor. J Biol Chem 278: 14237–14248, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheng YC, Prusoff W. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol 22: 3099–3108, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dirksen RT, Avila G. Altered ryanodine receptor function in central core disease: leaky or uncoupled Ca(2+) release channels? Trends Cardiovasc Med 12: 189–197, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Donham KJ. Health effects from work in swine confinement buildings. Am J Ind Med 17: 17–25, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Donham KJ, Popendorf W, Palmgren U, Larsson L. Characterization of dusts collected from swine confinement buildings. Am J Ind Med 10: 294–297, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Donham KJ, Rubino M, Thedell TD, Kammermeyer J. Potential health hazards to agricultural workers in swine confinement buildings. J Occup Med 19: 383–387, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Donham KJ, Scallon LJ, Popendorf W, Treuhaft MW, Roberts RC. Characterization of dusts collected from swine confinement buildings. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 47: 404–410, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dulhunty AF, Junankar PR, Stanhope C. Extra-junctional ryanodine receptors in the terminal cisternae of mammalian skeletal muscle fibres. Proc Biol Sci 247: 69–75, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fleischer S. Personal recollections on the discovery of the ryanodine receptors of muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 369: 195–207, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heederik D, Sigsgaard T, Thorne PS, Kline JN, Avery R, Bonlokke JH, Chrischilles EA, Dosman JA, Duchaine C, Kirkhorn SR, Kulhankova K, Merchant JA. Health effects of airborne exposures from concentrated animal feeding operations. Environ Health Perspect 115: 298–302, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hosoi E, Nishizaki C, Gallagher KL, Wyre HW, Matsuo Y, Sei Y. Expression of the ryanodine receptor isoforms in immune cells. J Immunol 167: 4887–4894, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Humerickhouse RA, Bidasee KR, Gerzon K, Emmick JT, Kwon S, Sutko JL, Ruest L, Besch HR., Jr High affinity C10-Oeq ester derivatives of ryanodine. Activator-selective agonists of the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release channel. J Biol Chem 269: 30243–30253, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Iowa State University National Agricultural Safety Database Livestock Confinement Dusts And Gases (Online). http://nasdonline.org/document/1627/d001501/livestock-confinement-dust-and-gases.html [May 2010].

- 18. Iversen M, Dahl R. Working in swine-confinement buildings causes an accelerated decline in FEV1: a 7-yr follow-up of Danish farmers. Eur Respir J 16: 404–408, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kimura I, Kondoh T, Tsuneki H, Kimura M. Reversed effect of caffeine on non-contractile and contractile Ca2+ mobilization operated by acetylcholine receptor in mouse diaphragm muscle. Neurosci Lett 127: 28–30, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lai FA, Erickson HP, Rousseau E, Liu QY, Meissner G. Purification and reconstitution of the calcium release channel from skeletal muscle. Nature 331: 315–319, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Larsson KA, Eklund AG, Hansson LO, Isaksson BM, Malmberg PO. Swine dust causes intense airways inflammation in healthy subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 150: 973–977, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Malmberg P, Larsson K. Acute exposure to swine dust causes bronchial hyperresponsiveness in healthy subjects. Eur Respir J 6: 400–404, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mathisen T, Von Essen SG, Wyatt TA, Romberger DJ. Hog barn dust extract augments lymphocyte adhesion to human airway epithelial cells. J Appl Physiol 96: 1738–1744, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mitloehner FM, Calvo MS. Worker health and safety in concentrated animal feeding operations. J Agric Saf Health 14: 163–187, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Motulsky H, Christopoulos A. Analyzing Data with GraphPad Prism. San Diego, CA: GraphPad Software Inc., 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 26. NationMaster Pork consumption per capita (most recent) by country (Online). http://www.nationmaster.com/graph/foo_por_con_per_cap-food-pork-consumption-per-capita [May 2010].

- 27. National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Washington, DC: National Academy, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Poole JA, Wyatt TA, Oldenburg PJ, Elliott MK, West WW, Sisson JH, Von Essen SG, Romberger DJ. Intranasal organic dust exposure-induced airway adaptation response marked by persistent lung inflammation and pathology in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 296: L1085–L1095, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Poole JA, Wyatt TA, Von Essen SG, Hervert J, Parks C, Mathisen T, Romberger DJ. Repeat organic dust exposure-induced monocyte inflammation is associated with protein kinase C activity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 120: 366–373, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Romberger DJ, Bodlak V, Von Essen SG, Mathisen T, Wyatt TA. Hog barn dust extract stimulates IL-8 and IL-6 release in human bronchial epithelial cells via PKC activation. J Appl Physiol 93: 289–296, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schiffman SS, Miller EA, Suggs MS, Graham BG. The effect of environmental odors emanating from commercial swine operations on the mood of nearby residents. Brain Res Bull 37: 369–375, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schwartz DA, Donham KJ, Olenchock SA, Popendorf WJ, Van Fossen DS, Burmeister LF, Merchant JA. Determinants of longitudinal changes in spirometric function among swine confinement operators and farmers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 151: 47–53, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Slager RE, Allen-Gipson DS, Sammut A, Heires A, DeVasure J, Von Essen S, Romberger DJ, Wyatt TA. Hog barn dust slows airway epithelial cell migration in vitro through a PKCalpha-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L1469–L1474, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thorne PS. Environmental health impacts of concentrated animal feeding operations: anticipating hazards-searching for solutions. Environ Health Perspect 115: 296–297, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thu KM. Public health concerns for neighbors of large-scale swine production operations. J Agric Saf Health 8: 175–184, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. United States Department of Agriculture Livestock and Poultry: World Markets and Trade. Circular Series DL&P 2–06, Foreign Agricultural Service, October 2006. Washington, DC: USDA, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vogelzang PF, van der Gulden JW, Folgering H, Heederik D, Tielen MJ, van Schayck CP. Longitudinal changes in bronchial responsiveness associated with swine confinement dust exposure. Chest 117: 1488–1495, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Von Essen SG, Auvermann BW. Health effects from breathing air near CAFOs for feeder cattle or hogs. J Agromedicine 10: 55–64, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Von Essen S, Donham K. Illness and injury in animal confinement workers. Occup Med 14: 337–350, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Von Essen SG, Scheppers LA, Robbins RA, Donham KJ. Respiratory tract inflammation in swine confinement workers studied using induced sputum and exhaled nitric oxide. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 36: 557–565, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wyatt TA, Sisson JH, Von Essen SG, Poole JA, Romberger DJ. Exposure to hog barn dust alters airway epithelial ciliary beating. Eur Respir J 31: 1249–1255, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wyatt TA, Slager RE, Devasure J, Auvermann BW, Mulhern ML, Von Essen S, Mathisen T, Floreani AA, Romberger DJ. Feedlot dust stimulation of interleukin-6 and -8 requires protein kinase C epsilon in human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L1163–L1170, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]