Abstract

The murine epidermis contains resident T cells that express a canonical γδ TCR. These cells arise from fetal thymic precursors and use a TCR that is restricted to the skin in adult animals. These cells assume a dendritic morphology in normal skin and constitutively produce low levels of cytokines that contribute to epidermal homeostasis. When skin is wounded, an unknown antigen is expressed on damaged keratinocytes. Neighboring γδ T cells then round up and contribute to wound healing by local production of epithelial growth factors and inflammatory cytokines. In the absence of skin γδ T cells, wound healing is impaired. Similarly, epidermal T cells from patients with healing wounds are activated and secreting growth factors. Patients with non-healing wounds have a defective epidermal T cell response. Information gained on the role of epidermal-resident T cells in the mouse may provide information for development of new therapeutic approaches to wound healing.

Introduction

Epithelial tissues line the external and internal surfaces of the body and provide an effective environment to protect the organism from the outside world. These tissues not only provide barrier functions but contain resident populations of cells with unique functions that contribute to homeostasis, surveillance, protection, and repair of the epithelia. Epithelial tissues including the skin, intestine, and lung are the largest organs in the body and together are the residence of the vast majority of lymphocytes in the body (1). Some of these immune cells have specialized functions related to their epithelial residence including the IgA-producing B cells of the intestine and the γδ T cells. There is a resident population of γδ T cells in epithelial tissues of all mammalian species (2). In contrast to the blood and peripheral lymphoid tissues where γδ T cells are typically a minor population, γδ T cells are the only resident lymphocytes in the murine epidermis. In other epithelial tissues, including the intestine and lung, the γδ T cells coexist withαβ T cells and other lymphocyte populations. Recent evidence from numerous laboratories has shown specialized roles for these γδ T cells in maintenance of epithelial homeostasis and response to tissue damage, infection, inflammation, and malignancy (3–5).

The epidermis is the outermost layer of skin. Murine epidermis is home to a unique population of γδ T cells, the dendritic epidermal T cells (DETC). The DETC express a canonical Vγ3Vδ1 TCR (alternate nomenclature Vγ5Vδ1) that is only expressed on these skin-resident T cells. This lack of TCR diversity and skin specific localization suggest a potential limited repertoire of skin-expressed antigens for the DETC that may direct DETC functions in the epidermis (4, 6).

The epidermis is under constant exposure to ultraviolet light, chemicals, allergens, and traumatic injury. Effective tissue repair requires cooperation of multiple cell types to produce varied growth factors and perform effector functions that orchestrate healing. Recent results have shown critical roles for DETC in recognition and response to epidermal injury (4, 6). An increasing number of patients suffer from chronic, non-healing wounds. The causes are not well understood and treatment strategies are often not satisfactory. Obtaining a better understanding of the contributions of DETC and other immune cells to wound healing may lead to development of effective new strategies for treatment of chronic wounds.

Development and homeostasis of epidermal γδ T cells

There are several key features of the development and homeostasis of DETC that contribute to their roles in wound healing. Strikingly, the TCR γ and δ genes are rearranged and expressed in an ordered manner during thymic ontogeny and T cells expressing specific Vγ and Vδ gene pairs migrate from the developing thymus to take up residence in specific epithelial tissues (Figure 1). A series of programmed differentiation events coupled with cellular selection processes proceed in a systematic order to produce functional T cells (reviewed in (7, 8)). The γδ T cells that localize in epithelial tissues have mainly tissue-specific TCRs with limited or no diversity. This is in sharp contrast with the highly diverse γδ TCRs expressed by γδ T cells found in peripheral lymphoid organs and blood. The first TCR genes that are expressed on developing murine fetal thymocytes are Vγ3 paired with Vδ1. Unexpectedly, the TCR expressed by these cells is invariant with no junctional diversity due to the lack of expression of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, gene accessibility, and recombination signal sequence restrictions at this stage of fetal development, coupled with cellular selection processes (7, 9, 10). This results in a limited window of time in which these TCR genes are accessible for rearrangement, effectively limiting development of Vγ3Vδ1+ thymocytes to a discrete stage of development. Vγ3Vδ1+ thymocytes are not generated in the adult thymus. These Vγ3Vδ1+ cells migrate from the fetal thymus to the epidermis where they expand to homeostatic numbers (7), conform to a dendritic morphology to facilitate interactions with multiple neighboring epithelial cells, and remain throughout life.

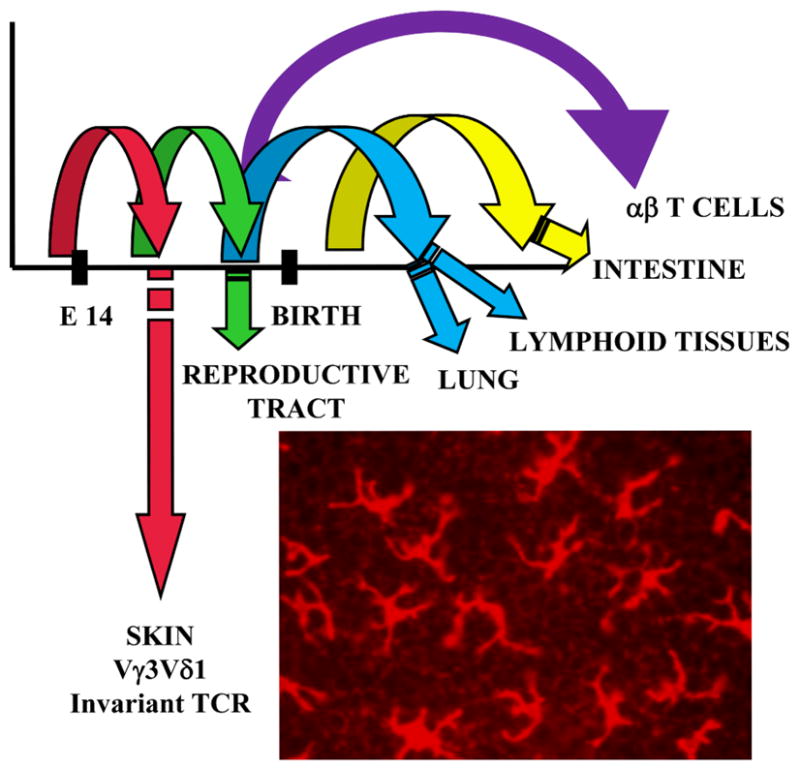

Figure 1.

DETC arise from fetal thymic precursors. TCR γ and δ chains are expressed in an ordered manner during development, with waves of cells expressing distinct γδ TCR exiting the thymus to populate specific epithelial tissues. The Vγ3Vδ1 TCR is rearranged and expressed early in fetal ontogeny. These cells migrate to the skin where they assume a dendritic morphology and persist in the adult mouse.

The epidermis is the only site in the adult mouse containing cells that express this TCR. Since DETC are the only resident T cells and the Vγ3Vδ1 TCR is invariant, the epidermis is populated by a monoclonal population of T cells. This complete absence of receptor diversity suggests that only a single or limited repertoire of antigens can be recognized by DETC. Recognition of a single foreign peptide antigen would severely limit the potential functional effectiveness of this population of cells suggesting the possibility of recognition of ligands quite different from those seen by αβ T cells. Antigens for γδ T cells, including DETC, are not well characterized and no paradigm exists to provide clues about antigen candidates. However, evidence from multiple laboratories indicates that the DETC recognize a self ligand(s) expressed by neighboring keratinocytes following damage or disease (3, 4, 6). Recognition of a conserved consequence of trauma may allow these monoclonal T cells to be broadly reactive to any form of epithelial stress rather than highly specific for a single pathogen. Studies are in progress to identify the specific keratinocyte antigen recognized by DETC.

In addition, cytokines play key roles in DETC development by providing differentiation, proliferation, survival and migration signals. Mice deficient in expression of IL-2Rβ, IL-7, IL-7R, IL-15 and IL-15R all have reduced numbers or lack DETC in the skin (11, 12). In addition, mice that lack expression of transcription factors Runx3, that regulates expression of IL-2Rβ, and the E protein E47, that regulates IL-7R expression, have defects in γδ T cell development and lack DETC (13, 14). IL-2 and IL-15 provide essential signals for survival and expansion of DETC precursors in the fetal thymus and after migration to the skin (11, 12). DETC precursors express IL-7R and signals provided by IL-7 have been shown to promote recombination and transcription of TCR γ genes as well as increased expression of anti-apoptotic proteins (12). These cytokine signals coordinate with molecular rearrangement mechanisms to allow DETC development to proceed.

There has been some controversy over the years about the role of cellular selection in DETC development. Development of T cells in the epidermis is not dependent on expression of the Vγ3 or Vδ1 TCR since mice deficient in these genes had DETC with alternate TCR and mice lacking all γδ T cells have αβ TCR-expressing DETC (15). There is evidence that positive selection is necessary to coordinate expression of chemokines receptors, such as CCR10/CCL27, and cytokine receptors, including IL-7R and IL-15R, that control thymic egress and homing to the epidermis (16). The Skint gene family was recently described to be expressed only by epithelial cells in the skin and thymus (17). Mice with a spontaneous mutation in Skint1 have greatly reduced Vγ3Vδ1+ DETC in the epidermis. Skint1 does not appear to directly bind to the TCR but is able to mediate critical interactions during DETC development. Although the mechanism of action is not fully defined, the Skint1 gene product is clearly required for maturation and expansion of DETC precursors in the thymus. The restrictions in early fetal gene rearrangement with specific signals from cytokines and Skint1 work together to provide the early window during ontogeny for development of DETC that is missing in the adult.

Roles of epidermal T cells during tissue repair

γδ T cells have been implicated as early and rapid responders to tissue damage. Their location in barrier tissues such as the skin, lung and intestine makes them an ideal candidate for participating in protecting the organism from infection and maintaining tissue homeostasis. Efficient restoration of barrier function is precisely orchestrated with a complexity that has been frustratingly difficult to replicate in patients with nonhealing wounds. The earliest events in wound repair responses include cellular damage itself, which initiates stress signals relayed by the epithelial cells residing at the front line of injury. Damaged, stressed, or transformed keratinocytes express an unknown antigen that activates DETC in a TCR-mediated fashion in cell culture. A rapid response by skin γδ T cells is evident in vivo by the dynamic morphology change of the epidermal γδ T cells within hours of tissue damage (18) (Figure 2 and unpublished data). These early activation responses in wound repair by the epithelial cells themselves and their adjacent γδ T cell neighbors cue responses by other cells types in the wound environment.

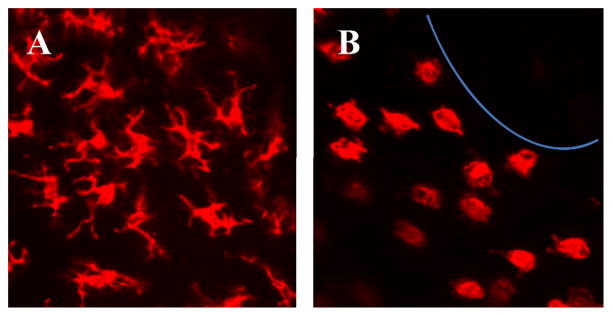

Figure 2.

DETC morphology changes in response to tissue damage. DETC present in normal epidermis (A) have a dendritic morphology. DETC located around a wound (B) become rounded and this morphology change correlates with initiation of a functional response. Epidermal sheets from a C57BL/6J mouse were stained with PE-anti-γδ TCR (mAb GL-3) and confocal images were acquired with a 40X objective.

Several models of wound healing have been established to investigate the role of DETC in wound repair in vivo, including full-thickness punch biopsy wounds and burn wounds. Mice lacking γδ T cells exhibit a delay in wound closure when administered punch biopsy wounds (18). This defect is attributed to the lack of growth factors, such as keratinocyte growth factors (KGFs), which are important for keratinocyte proliferation. Indeed fewer keratinocytes rapidly proliferate at the wound site in γδ T cell deficient mice as compared to control mice. γδ T cells isolated from the site of tissue damage express KGF-1 and KGF-2 RNA (18), produce TNF-α, and upregulate activation markers such as CD25 (19). The response of γδ T cells to damaged keratinocytes is rapid, as rounding of the DETC can be detected within 4 hours and cytokine production within 24 hours with KGF production following after 48 hours. This timing of activation correlates well with the defect in wound repair in TCRδ−/− mice which is most evident in the earliest stages of wound repair, resulting in a 2–3 day delay in complete wound closure (18). Epidermal T cell responses to tissue damage in mice require the keratinocyte-responsive γδ TCR, as αβ TCR+ cells that reside in the epidermis of TCRδ−/− mice are unable to produce cytokines at the wound site (19).

Wound repair occurs in a series of 4 phases that are required for rapid and complete healing. Healing is initiated by the development of a fibrin clot. This is followed by the inflammatory phase in which various cell types such as neutrophils, macrophages, and T cells infiltrate the wound site over a seven day period. The reepithelialization phase proceeds in response to factors produced by both resident and infiltrating cells. The final phase of tissue repair is the remodeling phase that can extend for weeks or longer as extracellular matrix is deposited and a scar is formed. Regulation of reepithelialization or keratinocyte proliferation and migration during wound repair is important for modulating skin closure. Growth factors such as KGF-1 and -2 are known to regulate keratinocyte proliferation, but are not produced by keratinocytes themselves. Skin γδ T cells produce both KGFs and IGF-1 within 2 days post-injury, which positively impacts the number of proliferating keratinocytes at the wound site (19, 20). DETC participation in wound repair is regulated by the serine threonine kinase mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (21). Mice treated with rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR signaling, exhibit a delay in wound healing and defects in DETC rounding and cytokine production at the wound site.

γδ T cells exhibit immunoregulatory functions when skin homeostasis is disrupted by damage or inflammation. DETC regulate the infiltration of αβ T cells into the skin during atopic dermatitis, contact hypersensitivity reactions, and following wounding (6, 22). Migration of inflammatory cells into the wound site is required for complete and efficient wound repair. Mice lacking γδ T cells exhibit delayed infiltration of macrophages into the wound site (22). The decreased expression of KGFs due to the absence of γδ T cells results in decreased deposition of extracellular matrix molecules such as hyaluronan. Addition of KGF to the wound site restores hyaluronan levels. Hyaluronan is produced by both keratinocytes and skin γδ T cells. Conversely, molecules produced by γδ T cells have also been implicated in anti-inflammatory responses (23). Skin γδ T cells were shown to produce a lymphoid-associated thymosin-β4 variant that was able to suppress inflammation associated with contact dermatitis.

γδ T cells also participate in several aspects of healing from burn injuries (24). Mice lacking γδ T cells have a defect in the inflammatory phase of wound healing. Entry of inflammatory populations such as macrophages into the burn site is delayed in burn wounds from TCRδ−/−mice. Recently this defect in macrophage entry into the burn site has been attributed to the DETC (25). Peripheral γδ T cells also play a role in neutrophil infiltration of other tissues during the inflammatory phase of wound repair (22). Together the full-thickness wound and burn injury models suggest that DETC participate in tissue repair, likely through the production of growth factors, cytokines and chemokines that regulate the epithelia and modulate migration of inflammatory cells.

The T cell composition of the epidermis differs between humans and most other mammals. While most mammals exhibit primarily γδ T cells in the epidermis, both αβ and γδ T cells are resident in human skin (26–31). The dermal T cells have been best characterized in man, but T cells are also found in the epidermis at a ratio of approximately 5αβ:1γδ T cell (31). Reports published from as early as 1920 claim that 2–40% of human epidermal cells, at a variety of physical locations, are T cells (29, 30). These conflicting reports over the years regarding the presence of T cells in human epidermis may be due in part to technical difficulties as many of the mAb used for the detection of T cells do not work well in immunohistochemical techniques. This has led to speculation that humans do not have a population of T cells in the epidermis with wound repair capabilities. However, this has recently been challenged as both αβ and γδ T cell populations isolated from human epidermis produce growth factors such as IGF-1 constitutively and epidermal T cell production of growth factors is increased following in vitro stimulation.

There is active secretion of growth factors in both T cell populations isolated from the skin of patients with acute wounds suggesting that the epidermal T cells may contribute to wound repair (31). Indeed, T cell stimulation increases the efficiency of tissue repair in wounded human skin cultured in vitro. In contrast, T cells isolated from chronic wounds do not produce IGF-1 and are not responsive to stimulation. These cells are unable to produce IL-2 and other cytokines upon ex vivo stimulation suggesting that the normal TCR signaling pathway is impaired in patients with nonhealing wounds.

While both αβ and γδ T cells isolated from human epidermis can produce cytokines and growth factors, it will be important to determine whether human epidermal αβ and γδ T cells exhibit differential functions. It is interesting to speculate that the primary role of the αβ T cell population may be to provide a defense against pathogens, while the γδ T cells may primarily function to regulate keratinocyte growth and survival. Understanding how these skin-resident T cell populations function may lead to identification of novel targets for therapeutic intervention in patients suffering from chronic, nonhealing wounds.

Molecules regulating epidermal T cell functions

Antigens for skin γδ T cells remain unknown. At this time little is known about antigens for any epithelial-resident γδ T cell population and no paradigm exists to provide clues to this critical information. The Skint1 gene product was an attractive candidate molecule for a DETC antigen due to its role in DETC development, but recent data does not support DETC TCR binding to this molecule (3). However, several lines of evidence do support the hypothesis that DETC antigens are expressed on keratinocytes located in wounded tissues. DETC in areas proximal to a wound site lose dendritic morphology and become rounded several hours post wounding while those T cells distal to the wound remain dendritic (Figure 2) (18). A comparison of DETC found around wounds with those in non-wounded areas indicates that morphology correlates with functional activity. The rounded DETC found near wounds are activated and secreting a variety of cytokines and growth factors while those distal to wounds retain a resting phenotype and secrete homeostatic levels of factors (18). Preliminary data using a soluble form of the DETC TCR indicates that DETC antigens are expressed rapidly and transiently on local keratinocytes following wounding (H.K. Komori, et al, manuscript submitted). This data fits nicely with published studies showing that DETC, and other epithelial resident γδ T cells, are “slightly activated” under normal conditions and express CD69 and CD25 as well as secrete low levels of certain cytokines (32), in contrast to typical T cell populations. This partial activation allows the DETC to be poised for fast, full activation in response to local trauma.

Interestingly, DETC do not express CD4, CD8 or CD28. The absence of typical sources of coreceptor and costimulatory signals for T cells raises the possibility that other molecules may contribute to full DETC activation. The activating receptor NKG2D is expressed by all γδ T cells including DETC. In general, NKG2D ligands are not significantly expressed by normal cells but can be upregulated following damage or disease raising the possibility for a role for NKG2D-mediated signals in DETC responses to wounding (3). A large number of ligands have been described for NKG2D and somewhat controversial data exists as to whether signals delivered by recognition of these ligands provide direct stimulation or costimulation to T cells. A new NKG2D ligand, H60c, was recently shown to be specifically expressed in the epidermis and on cultured keratinocytes (33). H60c was shown to provide potent costimulatory signals to DETC in vitro but was not sufficient to activate in the absence of TCR-mediated signals (33). Future work should determine if this ligand is upregulated on wounded keratinocytes and any role NKG2D-mediated costimulation may play in DETC wound healing functions.

We have recently identified a new costimulatory molecule for DETC that shares a signaling motif with CD28 (D.A Witherden, et al. manuscript in revision and P. Verdino, et al. manuscript in revision). JAML is a member of the Junctional Adhesion Molecule family and is expressed by DETC. DETC recognition of the JAML ligand CAR (Coxsackie and Adenovirus receptor) expressed by keratinocytes results in in vitro and in vivo costimulatory activation. This JAML-mediated costimulation was shown to provide signals necessary for effective DETC participation in wound healing (D. Witherden, et al., manuscript in revision).

These results suggest that rules for DETC activation differ significantly from typical αβ T cell activation requirements. The poised and ready nature of these cells fits well with recognition of unique antigens that are rapidly and transiently expressed. Evidence suggests that the unknown antigen is not a peptide that requires processing and presentation by MHC molecules (4, 34, 35), which does not occur rapidly. Recognition of costimulatory ligands whose expression is regulated in response to damage may provide an additional level of specialization for these cells. Together, the recognition of damage-induced antigens and costimulatory ligands appears to regulate effector functions of DETC that contribute to tissue repair in the epidermis (Figure 3).

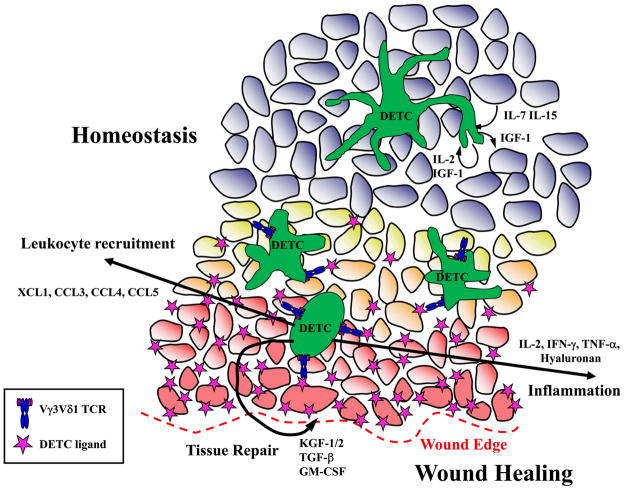

Figure 3.

Model of DETC functions during skin homeostasis and wound healing. DETC secrete low levels of cytokines in normal skin that contribute to epithelial homeostasis. Unknown antigens for DETC are expressed on keratinocytes in wounded tissue. DETC recognition of antigen and costimulation through molecules like JAML binding CAR leads to DETC rounding and activation to produce cytokines, growth factors and chemokines that contribute to a wound healing response.

Roles of other γδ T cells in tissue repair

Tissue-resident γδ T cells have been implicated in the repair of epithelia in other organs such as the intestine, lung, and cornea. Interestingly a population of γδ T cells has also been implicated in repair of skeletal injury (36). Various models have been established in these tissues to induce epithelial damage. The chemical dextran sulfate sodium salt (DSS) has been used to inflict damage on the intestinal epithelia, so that healing can be monitored once the chemical is removed from the drinking water (37). In the absence of γδ T cells, DSS-treated mice exhibit more severe disease and defects in the repair of intestinal damage (38, 39). Similar to the skin, epithelial cell proliferation in the intestine is known to restore barrier integrity. However, mice lacking γδ T cells exhibit decreased epithelial cell proliferation in response to DSS damage (38). A second method of inducing colitis is the intrarectal injection of 2, 4, 6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS). Depletion of γδ T cells in mice treated with TNBS results in increased mortality and more severe illness (40).

To identify whether KGFs also play a role in repair of the intestine, KGF−/− mice were examined in the DSS-induced colitis model. KGF−/− mice exhibit more severe illness and decreased levels of epithelial cell proliferation post-treatment (38). Thus, KGF is an important growth factor in the intestine as well as the skin. Therapeutic intervention with KGFs was shown to greatly reduce mortality and improve weight loss in DSS-treated mice and rats (41–43) and a recently developed bacterial delivery system may overcome some of the problems with stability that have plagued the use of growth factors to improve colitis in patients (44).

γδ T cells also reside within the epithelia of the lung (45) where they have been shown to play roles in controlling infection and asthma (46–48). Mice lacking γδ T cells are more susceptible to infection by N. Asteroides suggesting a role for γδ T cells in limiting infection (49). Data indicates that lung-resident γδ T cells may control infection by cytolysis and IFN-γ production (50, 51). While the mechanisms of defense against pathogens may initially be direct and pro-inflammatory, there is also evidence that γδ T cells down-modulate inflammatory responses to infectious agents thus preventing further damage to surrounding tissue. These anti-inflammatory functions include regulation of macrophage infiltration (52) and production of IL-10 (53).

This dual role for γδ T cells also appears to be the case in the enhancement and suppression of airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR). One subset of γδ T cells, Vγ1+ γδ T cells, can enhance AHR (54), while another subset, Vγ4+, is able to suppress AHR upon induction (46). The development of γδ T cells that modulate AHR is dependent on CD8α+ dendritic cells (55). In addition to pro- and anti-inflammatory roles, γδ T cells in the lung have been implicated in the repair of tissue after damage incurred by infection or ozone treatment (49). This suggests that similar to the skin and intestine, γδ T cells in the lung exhibit healing functions. Additional models of lung injury further support a healing role for γδ T cells in the lung. Bleomycin treatment induces epithelial damage and is followed by pneumonitis and fibrosis. TCRδ−/− mice exhibit defects in both inflammation and epithelial repair in the lung following bleomycin treatment (56). In addition, exposure to chlorine gas induces an increase in epithelial shedding in mice lacking γδ T cells (57). Taken together these studies indicate that lung γδ T cells play key roles in modulating the responses of the lung epithelia to various insults.

An additional model of epithelial repair has identified a role for γδ T cells in the epithelia of the cornea. Corneal repair is vital to the healing of abrasions on the surface of the cornea. γδ T cells make up a large portion of the resident limbal epithelial T cells. Similar to other epithelial tissues, mice lacking γδ T cells exhibit defects in the migratory and proliferative phases of corneal epithelial repair (58). In addition, TCRδ−/− mice exhibit reduced platelet localization to the limbus and reduced inflammation. ICAM-1 is expressed by corneal epithelium and functions as an adhesive ligand for LFA-1-dependent migration or retention of γδ T cells into damaged tissue (59). The role of γδ T cells in barrier tissue maintenance and regeneration is becoming clearer, however gaining knowledge about the molecules on γδ T cells that activate these responses and the disease environments that impair these responses require further investigation.

Conclusions

The DETC are an intriguing population of T cells with important roles in tissue repair. Significant key information is still unknown about TCR ligand(s) and the role of antigen recognition in development and function of these cells. It is hoped that as new information is obtained, this will contribute to the formation of a new paradigm for γδ T cell activation. Determination of γδ T cell contributions to wound healing in the mouse raised the possibility of similar functions in humans. Recent results demonstrating similar wound healing contributions by human epidermal T cells and that these functions were defective in patients with chronic, non-healing wounds has identified new potential targets for therapeutic intervention. Chronic wounds are an increasing clinical problem and information gained about the role of DETC in tissue repair in the mouse should help define new clinical treatment strategies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the current and past members of the Havran and Jameson labs for their hard work and contributions to our understanding of the functions of skin-resident γδ T cells. Special thanks to Olivia Garijo and Ryan Kelly for assistance with figures.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01AI36964 (WLH), R01AI64811 (WLH), R01GM80301 (WLH), R01DK80048 (JMJ), Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (JMJ) and L’Oreal (WLH).

Abbreviations in this paper

- DETC

dendritic epidermal T cells

- TCR

T cell receptor

- KGFs

keratinocyte growth factors

- CAR

Coxsackie and Adenovirus receptor

- DSS

dextran sulfate sodium salt

- TNBS

2, 4, 6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid

- AHR

airway hyperresponsiveness

References

- 1.Hayday A, Viney JL. The ins and outs of body surface immunology. Science. 2000;290:97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5489.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Havran WL, Jameson JM, Witherden DA. Epithelial cells and their neighbors. III. Interactions between intraepithelial lymphocytes and neighboring epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G627–630. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00224.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayday AC. γδ T cells and the lymphoid stress-surveillance response. Immunity. 2009;31:184–196. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jameson J, Havran WL. Skin γδ T-cell functions in homeostasis and wound healing. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:114–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nestle FO, Di Meglio P, Qin JZ, Nickoloff BJ. Skin immune sentinels in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:679–691. doi: 10.1038/nri2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strid J, Tigelaar RE, Hayday AC. Skin immune surveillance by T cells--a new order? Semin Immunol. 2009;21:110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiong N, Raulet DH. Development and selection of γδ T cells. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:15–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayday AC, Pennington DJ. Key factors in the organized chaos of early T cell development. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:137–144. doi: 10.1038/ni1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uche UN, Huber CR, Raulet DH, Xiong N. Recombination signal sequence-associated restriction on TCRδ gene rearrangement affects the development of tissue-specific γδ T cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:4931–4939. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiong N, Zhang L, Kang C, Raulet DH. Gene placement and competition control T cell receptor γ variable region gene rearrangement. J Exp Med. 2008;205:929–938. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharp LL, Jameson JM, Witherden DA, Komori HK, Havran WL. Dendritic epidermal T-cell activation. Crit Rev Immunol. 2005;25:1–18. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v25.i1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ye SK, Maki K, Lee HC, Ito A, Kawai K, Suzuki H, Mak TW, Chien Y, Honjo T, Ikuta K. Differential roles of cytokine receptors in the development of epidermal γδ T cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:1929–1934. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murre C. Helix-loop-helix proteins and lymphocyte development. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1079–1086. doi: 10.1038/ni1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woolf E, Brenner O, Goldenberg D, Levanon D, Groner Y. Runx3 regulates dendritic epidermal T cell development. Dev Biol. 2007;303:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pennington DJ, Silva-Santos B, Hayday AC. γδ T cell development--having the strength to get there. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiong N, Kang C, Raulet DH. Positive selection of dendritic epidermal γδ T cell precursors in the fetal thymus determines expression of skin-homing receptors. Immunity. 2004;21:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyden LM, Lewis JM, Barbee SD, Bas A, Girardi M, Hayday AC, Tigelaar RE, Lifton RP. Skint1, the prototype of a newly identified immunoglobulin superfamily gene cluster, positively selects epidermal γδ T cells. Nat Genet. 2008;40:656–662. doi: 10.1038/ng.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jameson J, Ugarte K, Chen N, Yachi P, Fuchs E, Boismenu R, Havran WL. A role for skin γδ T cells in wound repair. Science. 2002;296:747–749. doi: 10.1126/science.1069639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jameson JM, Cauvi G, Witherden DA, Havran WL. A keratinocyte-responsive γδ TCR is necessary for dendritic epidermal T cell activation by damaged keratinocytes and maintenance in the epidermis. J Immunol. 2004;172:3573–3579. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharp LL, Jameson JM, Cauvi G, Havran WL. Dendritic epidermal T cells regulate skin homeostasis through local production of insulin-like growth factor 1. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:73–79. doi: 10.1038/ni1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mills RE, Taylor KR, Podshivalova K, McKay DB, Jameson JM. Defects in skin γδ T cell function contribute to delayed wound repair in rapamycin-treated mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:3974–3983. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jameson JM, Cauvi G, Sharp LL, Witherden DA, Havran WL. γδ T cell-induced hyaluronan production by epithelial cells regulates inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1269–1279. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girardi M, Sherling MA, Filler RB, Shires J, Theodoridis E, Hayday AC, Tigelaar RE. Anti-inflammatory effects in the skin of thymosin-β4 splice-variants. Immunology. 2003;109:1–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexander M, Daniel T, Chaudry IH, Choudhry MA, Schwacha MG. T cells of the γδ T-cell receptor lineage play an important role in the postburn wound healing process. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:18–25. doi: 10.1097/01.bcr.0000188325.71515.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daniel T, Thobe BM, Chaudry IH, Choudhry MA, Hubbard WJ, Schwacha MG. Regulation of the postburn wound inflammatory response by γδ T-cells. Shock. 2007;28:278–283. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318034264c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark RA, Chong B, Mirchandani N, Brinster NK, Yamanaka K, Dowgiert RK, Kupper TS. The vast majority of CLA+ T cells are resident in normal skin. J Immunol. 2006;176:4431–4439. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dupuy P, Heslan M, Fraitag S, Hercend T, Dubertret L, Bagot M. T-cell receptor-γδ bearing lymphocytes in normal and inflammatory human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;94:764–768. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12874626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ebert LM, Meuter S, Moser B. Homing and function of human skin γδ T cells and NK cells: relevance for tumor surveillance. J Immunol. 2006;176:4331–4336. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bos JD, Zonneveld I, Das PK, Krieg SR, van der Loos CM, Kapsenberg ML. The skin immune system (SIS): distribution and immunophenotype of lymphocyte subpopulations in normal human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:569–573. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12470172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foster CA, Yokozeki H, Rappersberger K, Koning F, Volc-Platzer B, Rieger A, Coligan JE, Wolff K, Stingl G. Human epidermal T cells predominantly belong to the lineage expressing αβ T cell receptor. J Exp Med. 1990;171:997–1013. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.4.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toulon A, Breton L, Taylor KR, Tenenhaus M, Bhavsar D, Lanigan C, Rudolph R, Jameson J, Havran WL. A role for human skin-resident T cells in wound healing. J Exp Med. 2009;206:743–750. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pennington DJ, Vermijlen D, Wise EL, Clarke SL, Tigelaar RE, Hayday AC. The integration of conventional and unconventional T cells that characterizes cell-mediated responses. Adv Immunol. 2005;87:27–59. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(05)87002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whang MI, Guerra N, Raulet DH. Costimulation of dendritic epidermal γδ T cells by a new NKG2D ligand expressed specifically in the skin. J Immunol. 2009;182:4557–4564. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chien Y-h, Konigshofer Y. Antigen recognition by γδ T cells. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:46–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Brien RL, Roark CL, Jin N, Aydintug MK, French JD, Chain JL, Wands JM, Johnston M, Born WK. γδ T-cell receptors: functional correlations. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:77–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colburn NT, Zaal KJM, Wang F, Tuan RS. A role for γδ T cells in a mouse model of fracture healing. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1694–1703. doi: 10.1002/art.24520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ni J, Chen SF, Hollander D. Effects of dextran sulphate sodium on intestinal epithelial cells and intestinal lymphocytes. Gut. 1996;39:234–241. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.2.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen Y, Chou K, Fuchs E, Havran WL, Boismenu R. Protection of the intestinal mucosa by intraepithelial γδ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14338–14343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212290499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsuchiya T, Fukuda S, Hamada H, Nakamura A, Kohama Y, Ishikawa H, Tsujikawa K, Yamamoto H. Role of γδ T cells in the inflammatory response of experimental colitis mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:5507–5513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoffmann JC, Peters K, Henschke S, Herrmann B, Pfister K, Westermann J, Zeitz M. Role of T lymphocytes in rat 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid (TNBS) induced colitis: increased mortality after γδ T cell depletion and no effect of αβ T cell depletion. Gut. 2001;48:489–495. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han DS, Li F, Holt L, Connolly K, Hubert M, Miceli R, Okoye Z, Santiago G, Windle K, Wong E, Sartor RB. Keratinocyte growth factor-2 (FGF-10) promotes healing of experimental small intestinal ulceration in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G1011–1022. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.5.G1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Egger B, Procaccino F, Sarosi I, Tolmos J, Buchler MW, Eysselein VE. Keratinocyte growth factor ameliorates dextran sodium sulfate colitis in mice. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:836–844. doi: 10.1023/a:1026642715764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miceli R, Hubert M, Santiago G, Yao DL, Coleman TA, Huddleston KA, Connolly K. Efficacy of keratinocyte growth factor-2 in dextran sulfate sodium-induced murine colitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:464–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamady ZZ, Scott N, Farrar MD, Lodge JP, Holland KT, Whitehead TR, Carding SR. Xylan regulated delivery of human keratinocyte growth factor-2 to the inflamed colon by the human anaerobic commensal bacterium Bacteroides ovatus. Gut. 2009 doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.176131. Published Online: 7 September. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Augustin A, Kubo RT, Sim GK. Resident pulmonary lymphocytes expressing the γδ T-cell receptor. Nature. 1989;340:239–241. doi: 10.1038/340239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hahn YS, Taube C, Jin N, Takeda K, Park JW, Wands JM, Aydintug MK, Roark CL, Lahn M, O'Brien RL, Gelfand EW, Born WK. Vγ4+ γδ T cells regulate airway hyperreactivity to methacholine in ovalbumin-sensitized and challenged mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:3170–3178. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zuany-Amorim C, Ruffie C, Haile S, Vargaftig BB, Pereira P, Pretolani M. Requirement for γδ T cells in allergic airway inflammation. Science. 1998;280:1265–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5367.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Born WK, Lahn M, Takeda K, Kanehiro A, O'Brien RL, Gelfand EW. Role of γδ T cells in protecting normal airway function. Respir Res. 2000;1:151–158. doi: 10.1186/rr26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.King DP, Hyde DM, Jackson KA, Novosad DM, Ellis TN, Putney L, Stovall MY, Van Winkle LS, Beaman BL, Ferrick DA. Cutting edge: protective response to pulmonary injury requires γδ T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1999;162:5033–5036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Selin LK, Santolucito PA, Pinto AK, Szomolanyi-Tsuda E, Welsh RM. Innate immunity to viruses: control of vaccinia virus infection by γδ T cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:6784–6794. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang T, Scully E, Yin Z, Kim JH, Wang S, Yan J, Mamula M, Anderson JF, Craft J, Fikrig E. IFN-γ-producing γδ T cells help control murine West Nile virus infection. J Immunol. 2003;171:2524–2531. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Egan PJ, Carding SR. Downmodulation of the inflammatory response to bacterial infection by γδ T cells cytotoxic for activated macrophages. J Exp Med. 2000;191:2145–2158. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.12.2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hsieh B, Schrenzel MD, Mulvania T, Lepper HD, DiMolfetto-Landon L, Ferrick DA. In vivo cytokine production in murine listeriosis. Evidence for immunoregulation by γδ+ T cells. J Immunol. 1996;156:232–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hahn YS, Taube C, Jin N, Sharp L, Wands JM, Aydintug MK, Lahn M, Huber SA, O'Brien RL, Gelfand EW, Born WK. Different potentials of γδ T cell subsets in regulating airway responsiveness: Vγ1+ cells, but not Vγ4+ cells, promote airway hyperreactivity, Th2 cytokines, and airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2004;172:2894–2902. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cook L, Miyahara N, Jin N, Wands JM, Taube C, Roark CL, Potter TA, Gelfand EW, O'Brien RL, Born WK. Evidence that CD8+ dendritic cells enable the development of γδ T cells that modulate airway hyperresponsiveness. J Immunol. 2008;181:309–319. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Braun RK, Ferrick C, Neubauer P, Sjoding M, Sterner-Kock A, Kock M, Putney L, Ferrick DA, Hyde DM, Love RB. IL-17 producing γδ T cells are required for a controlled inflammatory response after bleomycin-induced lung injury. Inflammation. 2008;31:167–179. doi: 10.1007/s10753-008-9062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koohsari H, Tamaoka M, Campbell HR, Martin JG. The role of γδ T cells in airway epithelial injury and bronchial responsiveness after chlorine gas exposure in mice. Respir Res. 2007;8:21. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Z, Burns AR, Rumbaut RE, Smith CW. γδ T cells are necessary for platelet and neutrophil accumulation in limbal vessels and efficient epithelial repair after corneal abrasion. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:838–845. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Byeseda SE, Burns AR, Dieffenbaugher S, Rumbaut RE, Smith CW, Li Z. ICAM-1 is necessary for epithelial recruitment of γδ T cells and efficient corneal wound healing. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:571–579. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]