Abstract

Botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs) are the most potent natural toxins known. The effects of BoNT serotype A (BoNT/A) can last several months, whereas the effects of BoNT serotype E (BoNT/E), which shares the same synaptic target, synaptosomal-associated protein 25 (SNAP25), last only several weeks. The long-lasting effects or persistence of BoNT/A, although desirable for therapeutic applications, presents a challenge for medical treatment of BoNT intoxication. Although the mechanisms for BoNT toxicity are well known, little is known about the mechanisms that govern the persistence of the toxins. We show that the recombinant catalytic light chain (LC) of BoNT/E is ubiquitylated and rapidly degraded in cells. In contrast, BoNT/A LC is considerably more stable. Differential susceptibility of the catalytic LCs to ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis therefore might explain the differential persistence of BoNT serotypes. In this regard we show that TRAF2, a RING finger protein implicated in ubiquitylation, selectively associates with BoNT/E LC and promotes its proteasomal degradation. Given these data, we asked whether BoNT/A LC could be targeted for rapid proteasomal degradation by redirecting it to characterized ubiquitin ligase domains. We describe chimeric SNAP25-based ubiquitin ligases that target BoNT/A LC for degradation, reducing its duration in a cellular model for toxin persistence.

Keywords: botulinum toxin, HECT domain, synaptic transmission, Clostridium, SNAP25

Botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs) are the most potent natural toxins known (1, 2). Seven BoNT distinct serotypes (A–G) block acetylcholine release from presynaptic terminals at neuromuscular junctions, thereby causing flaccid paralysis (2, 3). BoNTs are zinc metalloproteases comprising a 50-kDa catalytic light chain (LC) linked by disulfide bonds to the 100-kDa heavy chain (4). BoNTs transiently and reversibly inhibit synaptic transmission when their LCs cleave one of their target proteins at presynaptic termini. These proteins include synaptosomal-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP25), vesicle-associated membrane protein, and syntaxin (4). However, the duration of muscle paralysis varies among the serotypes. Both BoNT/A and BoNT/E target SNAP25. Interestingly, muscle paralysis caused by BoNT/A can last for several months, whereas the effects of BoNT/E are relatively short-lived (5).

Despite the importance of understanding the basis for the persistence of BoNT/A relative to other serotypes, the molecular basis for this persistence remains largely unresolved. Some studies have focused on differential persistence of SNAP25 cleavage products by BoNT/A and BoNT/E. The two toxins cleave SNAP25 at different sites (Fig. 1A), resulting in different-sized N- and C-terminal fragments (6). BoNT/A cleaves after amino acid 197, generating SNAP251–197/P197 and SNAP25198–206/P9, whereas BoNT/E cleaves after amino acid 180, giving SNAP251–180/P180 and SNAP25181–206/P26. Investigators using different cellular and in vivo systems have reached varied conclusions regarding whether differential stability of the SNAP25 proteolytic fragments plays a role in toxin persistence (5, 7–9).

Fig. 1.

Expression and localization of recombinant BoNT catalytic light chains. (A) Schematic of SNAP25 and proteolytic fragments generated from BoNT/A and BoNT/E. (B) Colocalization of BoNT/E and BoNT/A LCs in neuronal cells. (C) Design of a luciferase reporter for BoNT proteolytic activity. (D) Cells were transfected with plasmids encoding luciferase reporter and YFP, YFP-LCE, or YFP-LCA, and luminescence was measured with a luminometer 36 h posttransfection. Data shown are mean ± SEM (n = 3; P < 0.01 for YFP-LCA compared with YFP) in arbitrary relative luminescence units (RLU). (E) Cells were transfected as in 1D, treated with DMSO or 20 μM MG132 overnight, and lysates were probed with indicated antibodies.

Other studies have focused on the toxin itself as an explanation for the persistence of BoNT/A intoxication relative to BoNT/E. These studies have, of necessity, used indirect approaches such as muscle paralysis or SNAP25 cleavage as end points because of the extremely low levels of toxins necessary for synaptic inhibition. Administration of BoNT/E following BoNT/A resulted in the initial loss and subsequent reappearance of BoNT/A-cleaved SNAP25, demonstrating persistence of BoNT/A proteolytic activity (10). Sequential injection of BoNT/A and BoNT/E in any order resulted in long-lasting paralysis of rat muscles, further supporting the hypothesis that BoNT/A catalytic LC persists in vivo (11). The molecular basis for the persistence of BoNT/A LC is not clear. Overexpression studies in which the two LCs were expressed independently suggested that BoNT/A LC is localized to the plasma membrane, whereas BoNT/B and BoNT/E LCs are not. This differential localization has been suggested to underlie the persistence of BoNT/A LC (12), although the molecular basis by which localization translates into stability was not addressed.

In this study, we investigate the mechanistic basis for the difference in half-lives of BoNT/A and BoNT/E LCs. We report that BoNT/E LC is degraded rapidly by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) in cells, whereas BoNT/A LC is quite stable. The UPS is responsible for most regulated intracellular protein degradation. Ubiquitin ligases (E3) are the primary substrate-recognition components of the UPS. E3s interact with specific target proteins and mediate their ubiquitylation. Among the many cellular E3s, proteins that include a zinc-coordinated really interesting new gene (RING) finger are the largest class (13). We establish that the RING finger protein TNF-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) associates with BoNT/E LC, but not with BoNT/A LC, and targets BoNT/E LC degradation. Finally, we provide proof of principle that BoNT/A LC can be destabilized by retargeting well-characterized ubiquitin ligase domains to BoNT/A LC.

Results

Colocalization of BoNT/A and BoNT/E LCs.

The high A/T content of Clostridium genes makes their expression in mammalian cells challenging. To overcome this difficulty and to study the basis for toxin persistence, we constructed cDNAs encoding BoNT/A LC (LCA) and BoNT/E LC (LCE) with codons optimized for mammalian expression. To help visualize the localization of LCs in living cells, they were fused to YFP or RFP. To compare the subcellular localization of LCA and LCE directly, we cotransfected YFP-LCE and RFP-LCA in N18 neuroblastoma cells. Consistent with a previous report (12), LCA is localized primarily to the plasma membrane when expressed in neuroblastoma cells (Fig. 1B). LCA also can be found in some intracellular membranes and vesicles. Interestingly, LCE has a similar distribution in neuroblastoma cells (Fig. 1B). Confocal imaging showed that YFP-LCE and RFP-LCA colocalize (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1). This result suggests that persistence of BoNT/A LC cannot be explained by a difference in steady-state subcellular localization relative to BoNT/E LC.

To address the possibility that persistence might result from increased stability of the shorter BoNT/LC A-generated C-terminal fragment of SNAP25, we constructed a reporter consisting of luciferase fused to the C terminus of FLAG-tagged murine SNAP25 (Fig. 1C). BoNT/A cleaves the construct to generate a P197 and a C-terminal product corresponding to P9 fused to luciferase. Because the P9-containing fragment generated by BoNT/A cleavage bears an N-terminal Arginine (R198 of SNAP25), it is predicted to be degraded rapidly by the N-end rule (14). In contrast, BoNT/E cleavage yields the P180 fragment and a C-terminal product that is relatively stable. Consistent with this prediction, cotransfection of the reporter construct with BoNT/A LC resulted in more than 10-fold reduction in luciferase activity, whereas coexpression with BoNT/E LC resulted in only small changes in luciferase activity (Fig. 1D). Immunoblotting with an antibody against the N terminus of the construct confirmed proteolysis of the full-length SNAP25-luciferase reporter by YFP-LCA and YFP-LCE to generate the predicted fragments (Fig. 1E, Middle). The N-terminal fragments appeared relatively stable compared with the full-length reporter. Notably, the C-terminal fragment produced by BoNT/A proteolysis was barely detectable but accumulated in the presence of MG132, an inhibitor of the proteasome (Fig. 1E, Bottom). The rapid loss of the P9-containing fragment from BoNT/A proteolysis is not caused simply by fusion with luciferase, because fusion with another protein yields similar results (Fig. S2). These results confirm the activities of our recombinant BoNT/A and BoNT/E LCs in cells and demonstrate that the P9 fragment generated by BoNT/A is short-lived.

BoNT/E LC Is Ubiquitylated and Rapidly Degraded.

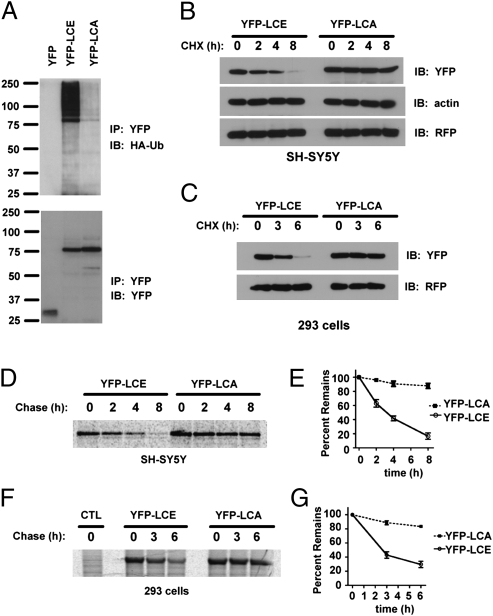

Examination of the top panels of Fig. 1E and Fig. S2 suggests that LCE accumulates in the presence of MG132. We therefore considered the possibility that YFP-LCE is degraded rapidly by the UPS. To determine if YFP-LCE is ubiquitylated, we cotransfected YFP-LCs and HA-tagged ubiquitin and treated the cells with MG132 to prevent proteasomal degradation. Immunoprecipitation of the LCs showed that YFP-LCE was heavily modified by ubiquitin compared with YFP-LCA, where detectable but considerably less ubiquitylation was observed (Fig. 2A). This result, together with the results shown in Fig. 1E, suggests that YFP-LCE is unstable as a consequence of ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation.

Fig. 2.

BoNT/E LC is ubiquitylated and degraded in cells. (A) Cells were transfected with plasmids encoding HA-tagged ubiquitin (Ub) and the indicated YFP plasmids. Cells were treated with MG132 and lysed under denaturing conditions. YFP-fused BoNT LCs were immunoprecipitated with GFP antibody. Ubiquitylated LCs were detected with HA-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with GFP monoclonal antibody. IB, immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitation. (B) Degradation of YFP-LCA and YFP-LCE in transfected human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells assessed by cycloheximide (CHX) chase. (C) Degradation of YFP-LCA and YFP-LCE in transfected HEK293 cells assessed by cycloheximide chase. (D) SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with YFP-LCA or YFP-LCE, and degradation of YFP-LCs was monitored by 35S pulse-chase. (E) Quantification of 35S pulse-chase experiments evaluating the degradation of YFP-LCA and YFP-LCE in SH-SY5Y cells (n = 3; values are mean ± SD). The percentage of 35S-labeled protein remaining is plotted as a function of chase time. (F) Degradation of YFP-LCA and YFP-LCE in HEK293 cells assessed by 35S pulse-chase. (G) Quantification of 35S pulse-chase experiments evaluating the degradation of YFP-LCA and YFP-LCE in HEK293 cells (n = 3; values are mean ± SD). The percentage of 35S-labeled protein remaining is plotted as a function of chase time.

Consistent with this hypothesis, treatment of human neuroblastoma cells with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide resulted in an almost complete loss of YFP-LCE over 8 h, whereas YFP-LCA was stable (Fig. 2B). Similar results were obtained with HEK293 cells (Fig. 2C) and a murine neuroblastoma cell line (Fig. S3). These results were confirmed by 35S pulse-chase experiments (Fig. 2 D–G), demonstrating that YFP-LCE was degraded rapidly (t1/2 ∼2.5 h), whereas YFP-LCA was considerably more stable (t1/2 > 10 h).

TRAF2 Interacts with BoNT/E LC and Promotes Its Degradation.

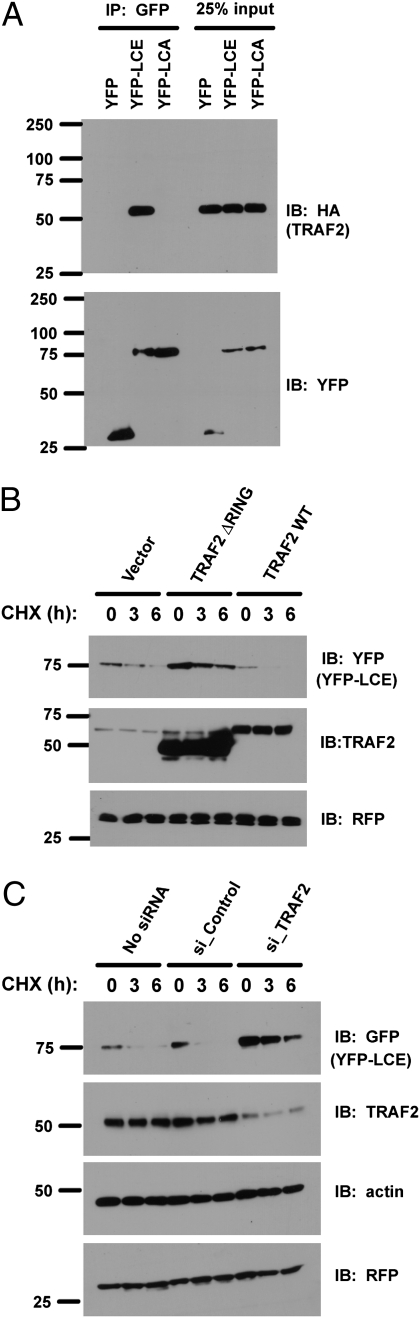

To understand the basis for the relative stability of BoNT LCs, we looked for interactions with E3s. Using mass spectrometry, we found two peptides specifically in LCE immunoprecipitates that correspond to TRAF2, a RING finger protein involved in TNF receptor signaling and implicated in ubiquitylation (15, 16). Coimmunoprecipitation experiments confirmed this interaction and established its specificity because TRAF2 was not detected in immunoprecipitates of either YFP-LCA or YFP control (Fig. 3A). To evaluate this interaction further, we expressed WT TRAF2 or a dominant-negative mutant lacking the RING finger domain (17). WT TRAF2 resulted in decreased stability of BoNT/E LC, whereas expression of the form lacking the RING finger resulted in an increased steady-state level and increased stability of this protein (Fig. 3B). To investigate further the significance of this interaction, we assayed the effects of TRAF2 siRNAs on the stability of BoNT/E LC (Fig. 3C). Knockdown of TRAF2 largely delayed the loss of YFP-LCE when cells were treated with cycloheximide, suggesting that TRAF2 associates selectively with BoNT/E LC and promotes its degradation.

Fig. 3.

TRAF2 interacts with the BoNT/E LC and promotes its degradation. (A) Cells were transfected with HA-tagged TRAF2 and the indicated plasmids. After 36 h, cells were treated with MG132 and lysed in RIPA buffer. YFP-fused BoNT LCs were immunoprecipitated (IP) with GFP antibody and immunoblotted (IB) with the indicated antibodies. (B) Cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids, and degradation of YFP-LCE was assessed by cycloheximide chase. (C) Cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, and degradation of YFP-LCE was assessed by cycloheximide chase.

Designing Ubiquitin Ligases to Enhance BoNT/A Degradation.

The previous results show that BoNT/E LC is unstable in cells, whereas BoNT/A LC is relatively stable. This observation suggests that differences in susceptibility to ubiquitin-dependent degradation probably underlie the differences in persistence of the toxins. A corollary of this hypothesis is that it should be possible to engage the UPS to enhance the degradation of BoNT/A LC, thereby shortening the duration of its effects.

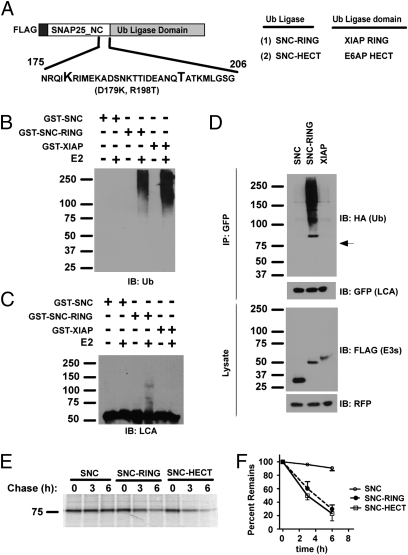

One approach to investigating this hypothesis would be to express an E3 designed to target BoNT/A LC. An obvious means of targeting BoNT/A is through its interactions with its substrate SNAP25. Toward this goal, we first generated a mutant of SNAP25 that is resistant to cleavage by both BoNT/A and BoNT/E (18, 19). We confirmed that SNAP25 with mutations (D179K, R198T) is resistant to both BoNT/A and BoNT/E proteolysis (Fig. S4). This noncleavable SNAP25 (SNC) served as the targeting domain for BoNT/A and BoNT/E LCs. We then designed E3s by fusing either the RING finger domain of X-linked mammalian inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) or the homologous to the E6-AP C-terminal (HECT) domain of E6-AP (20) to SNC (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

SNAP25-based ubiquitin ligase enhances BoNT/A LC degradation. (A) Design of a SNAP25-based ubiquitin ligase for targeting BoNT/A LC. The mutations (D179K, R198T) render mutant SNAP25 noncleavable (SNC) by BoNT/A and BoNT/E. (B) E3 activity of SNAP25-based RING finger ubiquitin ligase assessed by self-ubiquitylation in vitro. (C) Ubiquitylation of BoNT/A LC by SNAP25-based ubiquitin ligase in vitro. (D) Cells were transfected with YFP-LCA, HA-tagged ubiquitin, and the indicated plasmids. Cells were treated with MG132. YFP-LCA was immunoprecipitated (IP) with GFP antibody, and immunoblotted (IB) with the indicated antibodies. Arrow indicates migration of unmodified YFP-LCA. Expression of the ubiquitin ligases was assessed by immunoblotting total-cell lysates with FLAG antibody. (E) Cells were transfected with YFP-LCA and the indicated plasmids. Degradation of YFP-LCA was assessed by 35S pulse-chase. (F) Quantification of 35S pulse-chase experiments evaluating the effects of SNAP25-based ubiquitin ligases on YFP-LCA degradation (n = 3; values are mean ± SD). The percentage of 35S-labeled protein remaining is plotted as a function of chase time.

The activity of these fusion proteins was confirmed by self-ubiquitylation in vitro (Fig. 4B and Fig. S5A) (21). In addition, both SNC-RING and SNC-HECT are specifically capable of promoting ubiquitylation of recombinant BoNT/A LC in vitro (Fig. 4C and Fig. S5B).

Expression of SNC-RING or SNC-HECT reduced the steady-state levels of YFP-LCA in cells, whereas coexpression of SNC alone had no effect on the levels of YFP-LCA (Fig. S6A). Consistent with these E3s targeting LCA for ubiquitin-dependent degradation, expression of SNC-RING dramatically increased the steady-state ubiquitylation of YFP-LCA in cells (Fig. 4D). The effect is specific, because neither SNC alone nor XIAP, which showed similar E3 activity but lacks a BoNT/A LC targeting domain, promoted the YFP-LCA ubiquitylation. Similarly SNC-HECT enhanced the ubiquitylation of YFP-LCA in cells, whereas E6-AP had little effect (Fig. S6B). To determine whether these “designer” ubiquitin ligases enhanced BoNT/A LC degradation, 35S pulse-chase experiments assessing YFP-LCA stability were carried out. This analysis confirmed that SNC-RING and SNC-HECT enhanced the degradation of YFP-LCA (Fig. 4 E and F).

Cellular Model for BoNT/A Persistence.

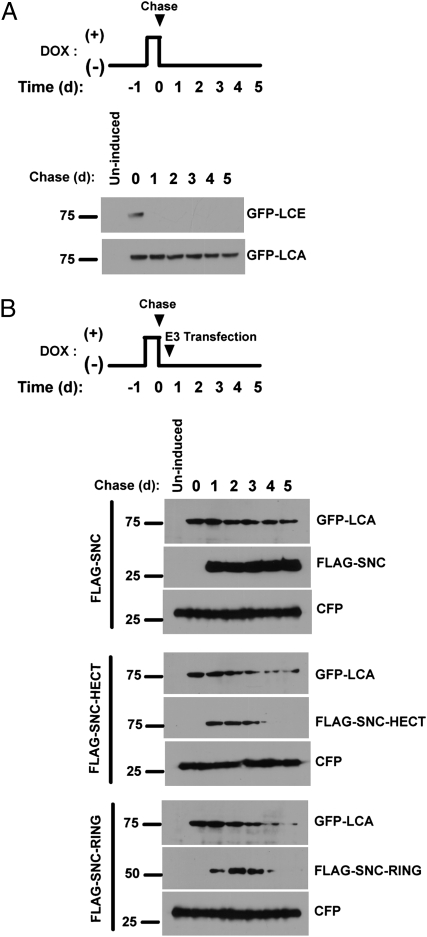

In the previous experiments, we showed that cotransfection of designer E3s can enhance degradation of BoNT/A LC. An important question is whether these E3s reduce persistence of BoNT/A LC in cells when expressed after the toxin has entered cells. To address this question, we developed a cellular model for BoNT/A persistence based on tetracycline-inducible expression of GFP-LCs. Flp-in/T-REX/293 cells transfected with inducible GFP-LCs were induced with doxycycline (a synthetic tetracycline) to express GFP-LCs. After 16 h, cells were washed and cultured in doxycycline-free medium. As expected, GFP-LCE was short-lived, disappearing almost completely 24 h after doxycycline withdrawal (Fig. 5A). In contrast, GFP-LCA persisted for at least 5 d. This inducible system therefore captures the essential feature of BoNT LC stability. The chase was limited to 5 d, because the cells became confluent by this time.

Fig. 5.

SNAP25-based ubiquitin ligases reduce the duration of BoNT/A LC in a cellular model of BoNT persistence. (A) Cells were induced with doxycycline for 16 h to express GFP-LCE and GFP-LCA. The persistence of YFP-LCs was monitored following doxycycline withdrawal. (B) Cells were induced with doxycycline to express GFP-LCA and cultured in doxycycline-free medium. After 8 h, cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids, and the stability of GFP-LCA was monitored. Cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) served as indicator of transfection efficiency.

We next tested whether expression of the designer E3s following induction of BoNT/A LC reduces the stability of the toxin. The experiment was performed as in Fig. 5A, except that cells were transfected with ubiquitin ligases 8 h following doxycycline withdrawal. Expression of SNC caused little change to the stability of GFP-LCA (Fig. 5B, Top). In contrast, expression of SNC-RING or SNC-HECT reduced the stability of GFP-LCA (Fig. 5B, Middle and Bottom). Cell proliferation was not affected by induced expression of the BoNT LCs or expression of the E3s. These results show that expression of ubiquitin ligases designed to target BoNT/A LC can reduce the levels of the toxin protease within cells.

Discussion

A salient feature of BoNT/A is the long-lasting effect on muscle paralysis following exposure. Notably, BoNT/A shares the same substrate, SNAP25, as BoNT/E, but the effects of the latter are short-lived. It has been proposed that the long-lasting effects of BoNT/A occur because SNAP25 cleavage products from BoNT/A persist and function to inhibit vesicle fusion. This notion is supported by the ability of BoNT/E to reduce the duration of paralysis when coinjected with BoNT/A, presumably by further cleaving and thus inactivating the inhibitory N-terminal SNAP25 cleavage products (5). However, pulse-chase experiments reveal that the half-lives of intact SNAP25 and BoNT/A-cleaved SNAP25 are similar, ∼1 d in cultured neurons (22). In other studies, confocal imaging of neuromuscular junction preparations from Xenopus suggests that BoNT/A-cleaved SNAP25 is retained, providing support for this model (9). In this case, the authors based their conclusion on the finding that immunofluorescence with an antibody specific to the N terminus of SNAP25 remains unchanged compared with immunofluorescence with an antibody raised against the 12 C-terminal residues of SNAP25 (9). Here, we show that the C-terminal fragment generated by BoNT/A cleavage is degraded rapidly, as predicted by the N-end rule, suggesting that direct comparison of immunofluorescence of the N-terminal fragments with that of the respective C-terminal fragments is problematic. Similarly, earlier studies have led to the idea that the C-terminal fragments of SNAP25 can accumulate and inhibit synaptic function (7, 8). However, as shown herein, the P9 fragment from BoNT/A cleavage is degraded rapidly and is unlikely to accumulate to any significant level in cells.

An alternative, but not mutually exclusive, model for persistence of BoNT/A intoxication is that the stability of its catalytic LC is prolonged compared with that of other serotypes. This possibility is supported by the persistent BoNT/A proteolytic activity in spinal cord cultures (10) and the long duration of muscle paralysis following sequential injection of BoNT/A and BoNT/E in any order (11). The finding that the order of injection is inconsequential suggests that cleavage products are not responsible for the persistence observed. The reasons for the discrepancy between results reported by Eleopra et al. (5), where coinjection of the two toxins diminished BoNT/A duration, and those of Adler et al. (11) are not clear, but it is possible that coinjection of BoNT/E with BoNT/A could result in forms of interference that are not well understood or that differences in cell types, species, or experimental procedures may play a role.

Although most evidence supports persistent BoNT/A proteolytic activity, the molecular basis for the persistence of the BoNT/A LC is unclear. A major difficulty in addressing this issue is the inability to detect BoNT LCs because of the extremely low level of toxin protease present within an intoxicated synapse. This difficulty has been circumvented by expression of codon-optimized recombinant LCs in cells (12). Confocal imaging suggests that GFP-LCA is localized to the plasma membrane, whereas GFP-LCE or GFP-LCB appeared to be localized to intracellular membranes. Based on these results, it was proposed that the unique subcellular localization of BoNT/A LC might account for its persistence (12, 23). However, colocalization of the toxins within the same cell was not performed in those studies. In our study, BoNT/A and BoNT/E LCs are, in fact, colocalized within neuronal cells. Colocalization of BoNT/A and BoNT/E LCs is perhaps not surprising, because they both target the same substrate. This result suggests that different subcellular localizations cannot account completely for the persistence of BoNT/A LC.

We found that BoNT/E LC is ubiquitylated and rapidly degraded in cells, whereas BoNT/A LC is relatively stable. These results suggest that the susceptibility of the toxin catalytic LC to ubiquitin-dependent degradation may account for the observed persistence of the toxins. The short half-life of BoNT/E LC could be caused in part by the selective association of the RING finger E3 TRAF2 (reviewed in ref. 16), which is involved in TNF signaling, with BoNT/E LC. Consistent with this possibility, depletion of TRAF2 with siRNAs stabilized BoNT/E LC, suggesting that TRAF2, perhaps together with its recently identified cofactor, sphingosine-1-phosphate, is required for BoNT/E LC degradation (24). Whether TRAF2 functions directly as an E3 for BoNT/E or works together with other E3s now becomes of great interest, as does the molecular basis for the differential association of the two LCs with TRAF2.

The finding that BoNT/E LC is targeted by the UPS raises the possibility that BoNT/A LC is targeted similarly, albeit with lower efficiency. Whether the difference between the two serotypes is caused by a low-affinity interaction with TRAF2 in the case of BoNT/A LC or by other mechanisms awaits determination. In any case, our findings led us to assess whether we might engage the ubiquitin system to target this extremely potent neurotoxin for degradation.

Previous approaches to retargeting E3s to proteins that are not normally their targets have taken advantage of the modular nature of cullin-containing E3s by using chimeric F-box proteins or small bridging molecules (25–28). These approaches have been used successfully to target clinically important molecules, including the Retinoblastoma protein as well as androgen and estrogen receptors. We have used a different approach, changing the substrate of the BoNT/A and /E proteases into a means of targeting for degradation by engineering SNAP25 to be resistant to both forms of BoNT (SNC) and directly fusing this mutant SNAP25 to ubiquitin ligase domains. The use of a natural substrate of BoNT as the targeting domain makes it likely that the resulting E3 will be localized to the appropriate subcellular domains as BoNT/LC. We show that both a RING finger and a HECT domain fused in this way can target BoNT/A LC to the UPS. Although these results suffice for proof of concept, it is clear that other targeting domains would be needed when designing ubiquitin ligases for therapy. The interaction of SNAP25 with other Snap receptors (SNAREs) is essential for synaptic vesicle docking and fusion. A SNAP25-based ubiquitin ligase potentially could degrade other components of the SNARE complex. Recombinant antibody fragments to the toxin catalytic subunit might be attractive candidates for such targeting domains.

In considering the efficacy of such a “retargeting” strategy, it is important that these ligases be able to function in cells in which BoNT is already expressed. We provide proof of principle for this condition through a cellular model for BoNT/A persistence based on inducible expression of BoNT LCs. This model should be of use for testing other therapeutic approaches to reducing BoNT/A LC levels and reducing persistence.

In this study, we have demonstrated that the relative persistence of BoNT/A LC compared with BoNT/E LC can be explained in part by the selective targeting of the latter to the UPS by TRAF2. This observation should provide a conceptual framework for designing drugs that shorten the duration of BoNT/A and engineering BoNT persistence to optimize clinical applications. We also have provided proof of principle that the persistence of BoNT/A LC can be overcome by targeting it for proteasomal degradation using designer ubiquitin ligases. These findings now open a way for attacking BoNT/A LC persistence either through delivery of designer ubiquitin ligases, such as those described herein, or through the use of small molecules capable of directly entering cells and retargeting other ubiquitin ligases to BoNT/A. The potential efficacy of such approaches is not limited to BoNT and should be considered in other infectious diseases where a specific intracellular pathogenic protein can be identified and where there is the potential for significant and widespread risk to the population should the pathogen be weaponized.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids.

We constructed synthetic genes for BoNT/A and BoNT/E LCs using preferred codon usage for Escherichia coli and mammals. FLAG-tagged murine SNAP25 was generated by PCR and subcloned into pcDNA3.1+ vector. Luciferase was subcloned into pcDNA3.1+ FLAG-SNAP25 to construct the reporter. To construct E3s targeting BoNT LCs, we first generated the SNAP25 mutant (SNC) resistant to both BoNT/A and /E proteolysis. E3 domains were generated by PCR and subcloned into pcDNA3.1+ FLAG-SNC.

Details of plasmids, ubiquitylation assays, cell culture, antibodies, fluorescence microscopy, and luciferase assays are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Tetracycline-Induced Expression of BoNT LCs.

Transfected Flp-in/T-REX/293 cells (Invitrogen) were treated with 2 μg/mL doxycycline (Invitrogen) for 16 h to induce expression of the GFP-LCs. Cells were washed three times with serum-free medium and cultured in tetracycline-free medium. Chase began at this time (time = 0). For experiments involving E3s, cells were transfected with E3s or control 8 h after doxycycline withdrawal. Lysates were collected daily for 5 d. GFP-LCs were immunoprecipitated with GFP antibody. FLAG-tagged SNC and designer E3s were immunoprecipitated with FLAG M2 antibody.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Lorick and members of the Laboratory of Protein Dynamics and Signaling for helpful discussions; M. Metzger and Z. Kostova for critical reading of the manuscript; M. Zhou and T. Veenstra [Biomedical Proteomics Program, National Cancer Institute (NCI)] for mass spectrometry analysis; S. Lockett (Optical Microscopy Analysis Laboratory, NCI) for confocal imaging support; S. Zou, J. Shi, D. Yarnell, R. Kincaid, and E. Sum for excellent technical support; J. Lippincott-Schwartz (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development) for mRFP plasmids, J. M. Mukherjee (Tufts University) for monoclonal antibody against BoNT/A LC; and J. D. Ashwell (NCI) for TRAF2 plasmids. This research is supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health/NCI (Y.C.T., R.M., and A.M.W.), by the Veterans Affairs Biomedical and Laboratory Research Service (P.S.F.), by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grant N01-AI-30050 (to C.K., C.B.S., and G.A.O.), and by a Department of Defense Defense Threat Reduction Agency contract (G.A.O.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: G.A.O. has a financial interest in Synaptic Research, LLC, which is developing therapeutics for BoNT intoxication including designs based on ubiquitin ligases.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1008302107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Simpson LL. Identification of the characteristics that underlie botulinum toxin potency: Implications for designing novel drugs. Biochimie. 2000;82:943–953. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)01169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Habermann E, Dreyer F. Clostridial neurotoxins: Handling and action at the cellular and molecular level. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1986;129:93–179. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-71399-6_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jahn R, Niemann H. Molecular mechanisms of clostridial neurotoxins. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;733:245–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb17274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montecucco C, Schiavo G. Structure and function of tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins. Q Rev Biophys. 1995;28:423–472. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500003292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eleopra R, Tugnoli V, Rossetto O, De Grandis D, Montecucco C. Different time courses of recovery after poisoning with botulinum neurotoxin serotypes A and E in humans. Neurosci Lett. 1998;256:135–138. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00775-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binz T, et al. Proteolysis of SNAP-25 by types E and A botulinal neurotoxins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1617–1620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrer-Montiel AV, et al. The 26-mer peptide released from SNAP-25 cleavage by botulinum neurotoxin E inhibits vesicle docking. FEBS Lett. 1998;435:84–88. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gutierrez LM, et al. A peptide that mimics the C-terminal sequence of SNAP-25 inhibits secretory vesicle docking in chromaffin cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2634–2639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raciborska DA, Charlton MP. Retention of cleaved synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP-25) in neuromuscular junctions: A new hypothesis to explain persistence of botulinum A poisoning. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1999;77:679–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keller JE, Neale EA, Oyler G, Adler M. Persistence of botulinum neurotoxin action in cultured spinal cord cells. FEBS Lett. 1999;456:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00948-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adler M, Keller JE, Sheridan RE, Deshpande SS. Persistence of botulinum neurotoxin A demonstrated by sequential administration of serotypes A and E in rat EDL muscle. Toxicon. 2001;39:233–243. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernández-Salas E, et al. Plasma membrane localization signals in the light chain of botulinum neurotoxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3208–3213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400229101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deshaies RJ, Joazeiro CA. RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:399–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.101807.093809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varshavsky A. The N-end rule: Functions, mysteries, uses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12142–12149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xia ZP, Chen ZJ. TRAF2: A double-edged sword? Sci STKE. 2005 doi: 10.1126/stke.2722005pe7. 10.1126/stke.2722005pe7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen ZJ. Ubiquitin signalling in the NF-kappaB pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:758–765. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ivanov VN, Fodstad O, Ronai Z. Expression of ring finger-deleted TRAF2 sensitizes metastatic melanoma cells to apoptosis via up-regulation of p38, TNFalpha and suppression of NF-kappaB activities. Oncogene. 2001;20:2243–2253. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Sullivan GA, Mohammed N, Foran PG, Lawrence GW, Oliver Dolly J. Rescue of exocytosis in botulinum toxin A-poisoned chromaffin cells by expression of cleavage-resistant SNAP-25. Identification of the minimal essential C-terminal residues. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36897–36904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.36897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Washbourne P, et al. Botulinum neurotoxin E-insensitive mutants of SNAP-25 fail to bind VAMP but support exocytosis. J Neurochem. 1999;73:2424–2433. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0732424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheffner M, Huibregtse JM, Vierstra RD, Howley PM. The HPV-16 E6 and E6-AP complex functions as a ubiquitin-protein ligase in the ubiquitination of p53. Cell. 1993;75:495–505. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorick KL, et al. RING fingers mediate ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2)-dependent ubiquitination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11364–11369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foran PG, et al. Evaluation of the therapeutic usefulness of botulinum neurotoxin B, C1, E, and F compared with the long lasting type A. Basis for distinct durations of inhibition of exocytosis in central neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1363–1371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernández-Salas E, Ho H, Garay P, Steward LE, Aoki KR. Is the light chain subcellular localization an important factor in botulinum toxin duration of action? Mov Disord. 2004;19(Suppl 8):S23–S34. doi: 10.1002/mds.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alvarez SE, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate is a missing cofactor for the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF2. Nature. 2010;465:1084–1088. doi: 10.1038/nature09128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakamoto KM, et al. Development of Protacs to target cancer-promoting proteins for ubiquitination and degradation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2003;2:1350–1358. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T300009-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou P, Bogacki R, McReynolds L, Howley PM. Harnessing the ubiquitination machinery to target the degradation of specific cellular proteins. Mol Cell. 2000;6:751–756. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez-Gonzalez A, et al. Targeting steroid hormone receptors for ubiquitination and degradation in breast and prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:7201–7211. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakamoto KM, et al. Protacs: Chimeric molecules that target proteins to the Skp1-Cullin-F box complex for ubiquitination and degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8554–8559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141230798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.