Abstract

Purpose

To test the hypothesis that V02peak is positively correlated with the regression coefficients of the curve-linear relationship between VO2 and speed during a protocol consisting of submaximal walking and running.

Methods

19 healthy males (age 26.4 ± 6.4 yr.; height 179.9 ± 7.2 cm; weight 77.7 ± 8.7 kg; % fat 16.3 ± 7.3) and 21 healthy females (age 25.6 ± 4.9 yr.; height 167.2 ± 5.4 cm; weight 61.6 ± 7.7 kg; % fat 24.0 ± 6.8) underwent an incremental treadmill test to determine VO2peak, and on two separate days performed an exercise protocol consisting of treadmill walking on a level grade at 2.0 mph (54 m.min-1), 3.0 mph (80 m.min-1), and 4.0 mph (107 m.min-1), and running at 6.0 mph (161 m.min-1). Subjects exercised for 5 min at each velocity, with 3 min rest in between each exercise bout. Pulmonary ventilation (VE) and gas exchange were measured breath-by-breath each min. The average of VO 2 values obtained during the last two min of exercise for both exercise sessions was used in polynomial random coefficient regression (PRCR) analysis.

Results

In the PRCR analysis for walking speeds only, both linear (r = 0.31; p = 0.053) and quadratic (r = 0.35; p = 0.029) were modestly correlated with VO2peak. Steady-state VO2 during walking at 3.0 and 4.0 mph, and running at 6.0 mph, was also modestly correlated with VO2peak (r = 0.30 – 0.48).

Conclusion

The results confirm our hypothesis and suggest that, as walking speed increases, the increase in VO2 is positively correlated with the VO2peak. Our findings are consistent with the notion that cardiorespiratory fitness and exercise economy are inversely related.

Keywords: efficiency, exercise, aerobic capacity, quadratic, fitness

Introduction

Both exercise economy and maximum oxygen uptake (VO2) influence endurance performance (5, 21). Somewhat counterintuitively, an inverse relationship between VO2max and exercise economy has been demonstrated for cycling (7, 14, 16, 22) and running (19, 23). In studies of running, steady-state VO2 at a single speed typically has been used as a measure of economy (5, 9, 19, 23). In contrast, for cycling the linear relationship between VO2 and power output has been used to assess exercise efficiency (i.e., ΔVO2/Δwork rate, with the inverse of this relationship used to define cycling efficiency) (4, 7, 10, 14, 16, 18, 20). A positive correlation between ΔVO2/Δwork rate and VO2max has been reported (7, 14, 16). The reason for the inverse relationship between ΔVO2/Δwork rate and VO2max in cycling remains unclear, although muscle fiber type and mitochondrial factors may play a role (3, 4, 12, 18). Noakes (22) proposed that among competitive endurance athletes with similar performance characteristics, the relationship between VO2max and running/cycling economy will always be inverse, i.e., competitors with low VO2max compensating with higher movement economy in order to achieve the same performance (19, 22). Thus it is the peak work rate (or running speed) reached during a maximal exercise stress test that is the best predictor of endurance performance, with the VO2max achieved on the test being dependent upon both peak work rate (or running speed) achieved and the exercise economy of the performer (21,22). However, an inverse relationship between VO2max and ΔVO2/Δwork rate in cycling also has been reported for untrained persons (7, 16).

For walking, Hunter et al. (12) reported an inverse relationship between VO2max and walking economy in sedentary women. In that study walking economy was assessed at one speed, 3.0 miles per hour (mph). We are unaware of any published data that examines whether the slope of the VO2 –walking/running relationship is related to VO2max. Figures from previously published work indicate that the slope of the VO2 –walking/running relationship may vary considerably among individuals (5, 8, 17, 21). However, in these studies the relationships between VO2-treadmill speed slope and VO2max were not reported.

Therefore, we examined the relationship between VO2peak and submaximal exercise VO2 elicited during a walking/running protocol in men and women heterogeneous for cardiorespiratory fitness. Because the slope of the VO2-walking speed relationship is nonlinear (8, 17, 24), we analyzed data with a polynomial random coefficient regression model. We hypothesized that VO2peak would correlate positively with both linear and quadratic coefficients of the model.

Methods

Subjects

Fifty-two subjects (29 females; 23 males) between the ages of 19 and 40 enrolled in the study. Subjects were generally physically active, and none of the subjects was a competitive runner or race-walker. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject, and the University of Virginia's Institutional Review Board approved the study. A pre-participation medical history and exam was completed on each subject to ensure good health. Due to exclusions on the basis of exercise test data (see below), 21 females and 19 males were used for data analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics and oxygen uptake during treadmill exercise (Mean ± SD)

| Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 26.4 ± 6.4 | 25.6 ± 4.9 |

| Height (cm) | 179.9 ± 7.2 | 167.2 ± 5.4 |

| Weight (kg) | 77.7 ± 8.7 | 61 6 ± 7.7 |

| Body fat (%) | 16.3 ± 7.3 | 24.0 ± 6.8 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 65.9 ± 8.8 | 47.6 ± 5.3 |

| VO2peak (ml/kg/min) | 45.0 ± 6.2 | 40.0 ± 6.1 |

| Time to Exhaustion (min) | 26.5 ± 3.5 | 24.2 ± 3.4 |

| VO2 at 2.0 mph (ml/kg/min) | 10.6 ± 1.1 | 10.9 ± 1.3 |

| VO2 at 3.0 mph (ml/kg/min) | 13.3 ± 1.4 | 13.9 ± 1.9 |

| VO2 at 4.0 mph (ml/kg/min) | 19.5 ± 2.2 | 20.0 ± 2.0 |

| VO2 at 6.0 mph (ml/kg/min) | 33.2 ± 3.1 | 32.5 ± 3.4 |

Experimental design

Each subject reported to the exercise physiology laboratory on three occasions, each separated by at least 48 hours. On one occasion body fat percentage was determined by air displacement plethysmography (6) and incremental walking protocol was administered to assess VO2 peak. On each of the two other occasions subjects performed a routine involving walking and running (2). These two protocols were identical in nature and for a given subject were performed at the same time of day on each occasion. Subjects were instructed to come to the laboratory at least two hours post-absorptive, to not perform any exercise prior to the session on the day of the test, and to not engage in strenuous exercise on the day before the test.

Incremental treadmill walking protocol

A modified Balke protocol was performed on a motorized treadmill for determination of VO2peak. Subjects began walking at 3.3 mph (88 m.min-1), 0% grade for the first min. The grade was increased to 2% for one min, and then increased by 1% every min thereafter. If a 25% grade was reached, treadmill speed was increased by 0.5 mph (13.4 m.min-1) every min. The test was terminated at the point of volitional exhaustion. During the test verbal encouragement was given to all subjects. Subjects were not permitted to hold on to handrail supports at any time during the test. Pulmonary ventilation and gas exchange were measured breath-by-breath with the VmaxST portable metabolic measurement system (VIASYS, Yorba Linda, CA, USA). We previously reported that this system provides reliable measurements of VO2 during walking and running (2). Time to exhaustion averaged 24.5 ± 4.1 min. VO2peak was taken as the highest 30-s average during the test. To be included in the data analysis subjects had to have either a peak respiratory exchange ratio (R) ≥ 1.10 or a peak heart rate ≥ 90% of age-predicted maximum. Three subjects were excluded by these criteria. At exhaustion heart rate averaged 187 ± 11 beats per min (97.4 ± 6.1 percent of age-predicted maximum) and R averaged 1.14 ± 0.09.

Walk/Run Protocol

Upon arrival to the laboratory subjects were fitted with the VmaxST system. After a 5-min period of seated rest, subjects then walked on a motor-driven treadmill at 2.0 mph (53.6 m.min-1), 3.0 mph (80.5 m.min-1), and 4.0 mph (107.3 m.min-1), and ran at 6.0 mph (160.9 m.min-1). Subjects exercised for 5 min at each speed, with 3 min of rest (standing) between each exercise period. Ventilation and gas exchange were measured breath-by-breath during each min of each exercise bout, and VO2 was averaged over the last 2 min of exercise. This walk/run protocol was repeated for each subject (for purposes of assessing reliability of the VmaxST system, published previously (2)), and the average of the two trials was used in the statistical analysis. Nine subjects were excluded from the data analysis due to failure to achieve a steady-state VO2 during the run at 6.0 mph (steady-state defined as a < 100 ml/min increase in VO2 during the last 2 min of the test).

Statistical Analyses

The relationship between VO2 and walking/running speed was examined by way of polynomial random coefficient regression (PRCR). The VO2 (ml/kg/min) measurements at walking speeds of 2.0, 3.0 and 4.0 mph and at the running speed of 6.0 mph represented the response measurements in the PRCR analysis. Separate analyses were performed using all speeds in the same regression model (i.e., walking and running bouts combined) and for walking speeds only. Walking and running speed represented the predictor of VO2 in the PRCR analysis with a second order curve-linear polynomial model specification that included linear and quadratic terms. We also performed the same analyses with time to exhaustion included in the model as a predictor of VO2. Marginal PRCR coefficient estimates (i.e., average) and subject-specific intercepts and linear and quadratic coefficient best linear unbiased predictions (BLUPS) were derived by way of restricted maximum-likelihood. Statistical inferences with respect to the marginal regression PRCR coefficients were based on Type III F-tests. A p < 0.05 decision rule was utilized as the criterion for rejecting the null hypothesis that the PRCR marginal coefficient was equal to 0.

The correlations between VO2peak and the PRCR subject-specific linear and quadratic coefficient BLUPS were assessed by way of the univariate Pearson correlation coefficients. A p < 0.05 decision rule was utilized as the criterion for rejecting the null hypothesis of zero correlation.

The SAS PROC MIXED and PROC CORR procedures of SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary NC) were used to conduct the PRCR analysis and the Pearson univariate analyses, respectively.

Results

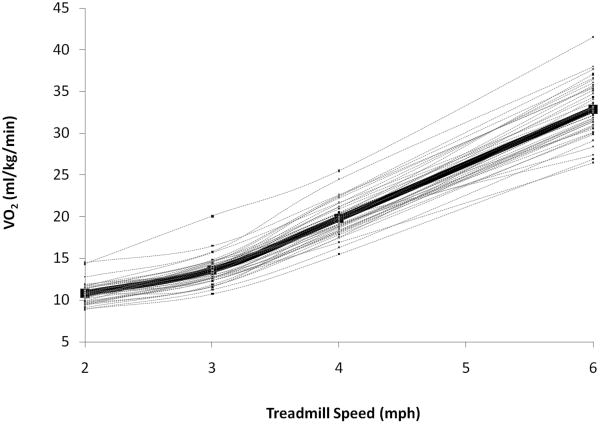

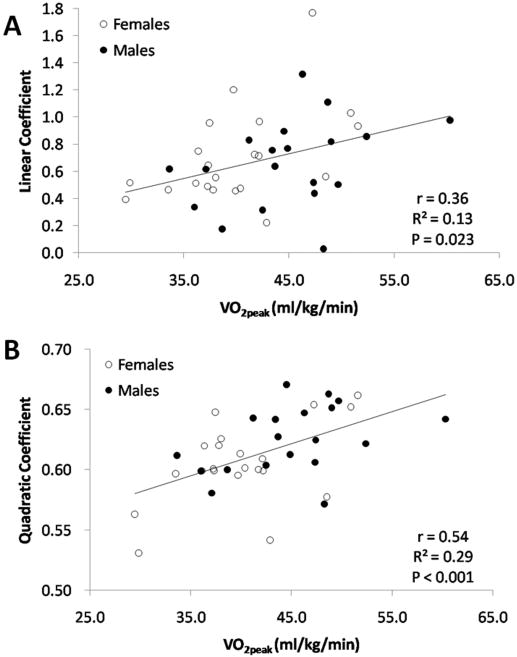

As expected, the relationship between VO2 and walking speed was curve-linear (Figure.1), with a significant quadratic coefficient (p < 0.0001) and a marginally significant linear coefficient (p = 0.0549) (Table 2). Both linear and (r = 0.0.36; p = 0.023) and quadratic (r = 0.54; p < 0.001) coefficients were significantly correlated with VO2peak (Figure 2). Including treadmill time to exhaustion to the random coefficient regression model did not improve predictions (p = 0.763).

Figure 1.

VO2 – treadmill speed relationship. Lines for each subject were generated using polynomial random coefficient regression (PRCR: see text for details) that included linear and quadratic coefficients. Solid dark line depicts the mean response.

Table 2.

Polynomial random coefficient regression model summary for the population (marginal) parameter estimates for the regression of VO2 on speed.

| Effect | Estimated β | Standard Error | T-statistic | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model includes walking and running | ||||

| Intercept | 6.70 | 0.64 | 10.5 | <0.0001 |

| Linear | 0.68 | 0.35 | 1.9 | 0.0549 |

| Quadratic | 0.62 | 0.04 | 14.4 | <0.0001 |

| Model Restricted to walking speeds only | ||||

| Intercept | 14.94 | 0.99 | 15.1 | <0.0001 |

| Linear | -5.37 | 0.70 | -7.7 | <0.000 |

| Quadratic | 1.64 | 0.11 | 14.2 | <0.0001 |

Figure 2.

Relationship between VO2peak and the linear (Panel A) and quadratic (Panel B) regression coefficients of the PRCR analysis depicted in Figure 1. n = 40.

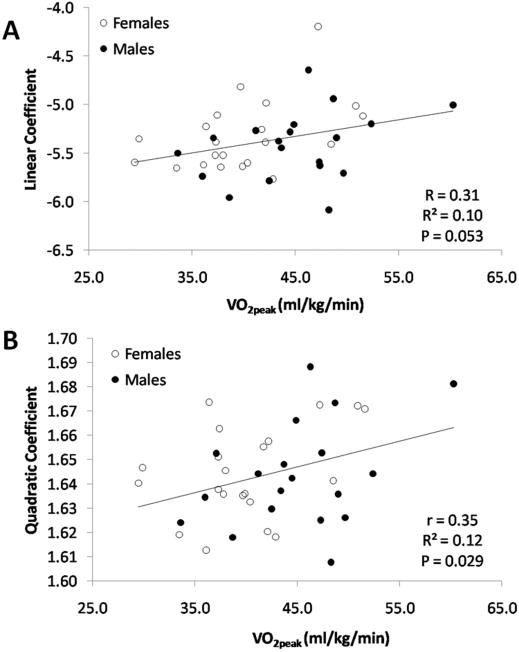

When the PRCR analysis was restricted to only the walking speeds, both linear and quadratic coefficients were significant (Table 2), and both linear (r = 0.31; p = 0.053) and quadratic (r = 0.35; p = 0.029) coefficients were correlated with VO2peak (Figure 3). There were no differences between men and women with regard to PRCR coefficients.

Figure 3.

Relationship between VO2peak and the linear (Panel A) and quadratic (Panel B) regression coefficients of the PRCR analysis depicted in Figure 1, using only the three walking speeds (2-4 mph) in = 40.

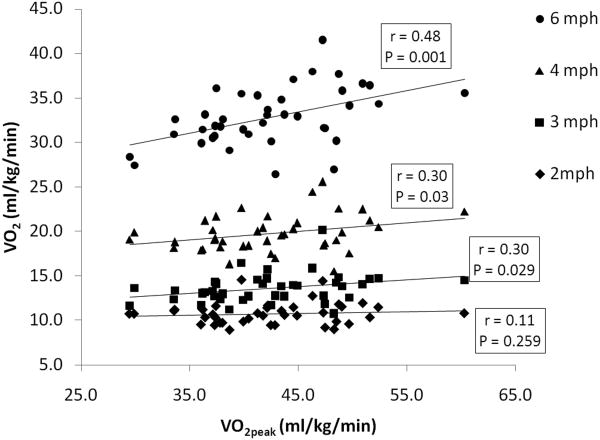

Steady-state VO2 at each speed was also positively correlated with VO2peak, with the strongest correlation at the running speed of 6 mph (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Relationship between VO2peak and steady-state VO2 at walking speeds of 2.0, 3.0, and 4.0 mph, and at the running speed of 6.0 mph. The correlations become increasingly stronger as treadmill speed increases. n = 40.

Discussion

Our finding of a positive relationship between VO2peak and the regression coefficients of the VO2-walking speed relationship confirms our hypothesis and suggests that what has been reported for cycling (4, 7, 10, 14, 16, 18, 20) also applies to walking. The higher the VO2peak of the subject, the greater is the increase in VO2 when speed is increased throughout a range of walking speeds from slow (2.0 mph) to brisk (4.0 mph). Because we obtained data on only one running speed, additional experiments are necessary to confirm that our findings extend to running.

The reason for including only one running speed was due to the fact that the original design of this study was to evaluate the reliability of a portable metabolic measurement system, and we focused primarily on walking speeds that would ensure steady-state VO2 (2). Nevertheless, the results for the two PRCR analyses (i.e., with and without the running speed in the analysis) yielded similar results (Table 2), and the correlations between VO2peak and the linear and quadratic regression coefficients from the models with and without the one running speed included in the analysis were qualitatively similar (Figures 2 and 3).

The results of our regression analyses are consistent with the findings of others who reported positive relationships between VO2max and steady-state VO2 in walking (12) and running (19, 23). Hunter et al. (12) reported a correlation of 0.28 between VO2 walking at 3.0 mph and VO2max in sedentary women, which is very close to the correlation of 0.30 that we found for our subjects (Figure 4). For running, Pate et al. (23) reported a correlation of 0.26 between VO2max and VO2 while running at 6.0 mph in a 188 men and women distance runners. This is lower than the correlation of 0.48 that we observed for our subjects (Figure 4). Compared to our subjects, Pate et al.'s subjects had higher VO2max values (50.3 ml/kg/min vs. 40-45 ml/kg/min), and slightly higher VO2 values for running at 6.0 mph (33.9 ml/kg/min vs. ∼32.8 ml/kg/min (Table 1)). The ∼3% higher VO2 at 6.0 mph in the subjects studied by Pate et al. is consistent with the notion that higher VO2max values are associated with lower economy (22).

Why increases in walking speed (or cycling power output) elicit greater increases in VO2 in subjects with higher VO2peak is not well understood. Muscular factors may be involved in cycling efficiency and exercise economy (3, 4, 12, 18). Buemann et al. (3) reported that cycling efficiency was reduced in subjects with a specific polymorphism of the uncoupling protein (UCP) 2 gene. Similarly, Mogensen et al. (18) reported that cycling efficiency was inversely correlated with muscle UCP 3 and positively correlated with type I fiber percentage. This latter observation is similar to that of Coyle et al. (4), who reported that cycling efficiency in experienced cyclists was correlated with type I muscle fiber percentage. In contrast, Mallory et al. (16) found that cycling efficiency was unrelated to type I muscle fiber percentage (r = 0.11) and to citrate synthase activity (r = 0.21) but was significantly inversely correlated with VO2peak (r = -51).

With respect to treadmill exercise, Hunter et al. (12) found that VO2 walking at 3.0 mph was positively correlated with type IIa muscle fiber percentage in gastrocnemius muscle of sedentary women, and that both of these variables were positively correlated with VO2max. Hunter et al. suggested that individuals with a high proportion of energetically inefficient type IIa muscle fibers will tend to be both less economical and have a greater oxidative capacity, with the greater “capacity” being a consequence of the higher O2 demand of the inefficient type IIa fibers (12). If true, and if recruitment of type II fibers is influenced by both the percentage of muscle comprised of type II fibers and the exercise intensity, it could help explain why the correlations between VO2peak and the linear and quadratic regression coefficients were higher when the running speed of 6.0 mph was included in the analysis (Figures 2 and 3). It also may help explain why the correlation between VO2peak and steady-state VO2 was highest for the running speed (Figure 4).

In contrast to the discussion above, Layec et al. (13) recently reported that the energy cost of muscle contraction was not different in trained and untrained subjects differing markedly in VO2max (67.1 ml/kg/min vs. 42.3 ml/kg/min). Muscle fiber characteristics of subjects were not obtained. Nevertheless, this study, in combination with some of the inconsistent findings described above, suggest that there may be factors other than skeletal muscle morphology and oxidative capacity that influence the slope of the relationship between VO2 and increases in work rate.

A number of anthropometric variables have been hypothesized to contribute to economy during walking and/or running, including leg length, stride characteristics and other biomechanical characteristics, body mass and weight distribution between the trunk and limbs (1, 12, 15, 23). We have no data to contribute to discussion of this issue. Selected exercise intensity (walking/running speed) could also affect assessment of economy. In the study Pate et al. (23), the running speed used to assess economy (6.0 mph; 10 min.mile-1 pace) was much slower than typical training pace (∼8.4 min.mile-1) of their subjects, and this may have influenced their results. However, Morgan and Daniels (19) reported a significant correlation of 0.59 between VO2max and submaximal VO2 in elite distance runners running at speeds typically encountered in daily training.

For walking and running studies, determination of economy typically involves measurement of steady-state VO2 at one or more selected speeds, without analysis of the characteristics of the VO2-speed relationship (1, 5, 12, 15, 17, 19, 23). However, it is apparent that considerable between-individual variation in the slope of the VO2-speed relationship exists (5, 19, 21). Our results demonstrate that, similar to a number of reports on cycling (7, 14, 16), the regression coefficients describing the curve-linear relationship between VO2 and walking speed are positively correlated with VO2peak.

A limitation of our study is that we only had three walking speeds. Our speeds, however, did encompass a range that is typically used for studies of energy expenditure during walking (1, 8, 12, 15). Speeds slower than 2.0 mph are below freely chosen walking speeds for young healthy adults (17), and speeds above 4.0 mph typically approach a transition speed in which subjects “walk-jog,” thus affecting gait. It is unlikely that inclusion of more speeds between 2.0 and 4.0 mph would have materially affected the PRCR analyses. Our subjects were asked to not eat or drink calorie- or caffeine-containing beverages for two hours prior to the exercise sessions. Two hours post-absorptive does not reflect a true fasted state and, therefore, metabolism may have been slightly affected by the subjects' previous meal. In order to control for this we tested the subjects at the same time of day and asked them to eat and drink the same before each session. We also did not control for stage in the menstrual cycle for the female subjects.

On the other hand, a major strength of the study is that VO2 values used in the PRCR analyses represented the average of two identical trials of treadmill walking/running for each subject. As previously reported, the VmaxST system used in the present study produces reliable measurements of VO2, with coefficients of variation of 5.5-7.5%, intraclass correlation coefficients of 0.77-0.90, and R2 of 0.88-.095 (2). Furthermore, we excluded subjects who appeared not to have achieved a VO2peak and who also appeared to have a significant slow component of VO2 at 6.0 mph (11).

In summary, we observed significant positive correlations between VO2peak and both linear and quadratic coefficients of the curve-linear relationship between VO2 and walking speed. These findings are similar those reported for cycling (7, 14, 16), and are consistent with the inverse relationship between VO2peak and economy demonstrated for submaximal steady-state walking (12) and running (19, 23). Because so much of the variance in the relationship is unexplained (Figures 2 and 3), understanding the causal factors will be challenging.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants RR00847 to the University of Virginia General Clinical Research Center, and R21 CA112323. Results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM.

Funding: NIH RR00847 to the University of Virginia General Clinical Research Center, and R21 CA112323.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise ® Published ahead of Print contains articles in unedited manuscript form that have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication. This manuscript will undergo copyediting, page composition, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered that could affect the content.

References

- 1.Allor KM, Pivarnik JM, Sam LJ, Perkins CD. Treadmill Economy in Girls and Women Matched for Height and Weight. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89(2):512–6. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.2.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blessinger J, Sawyer BJ, Davis C, Irving BA, Weltman A, Gaesser G. Reliability of the VmaxST portable metabolic measurement system. Int J Sports Med. 2009;30(1):22–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1038744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buemann B, Schierning B, Toubro S, Bibby BM, Sorenson T, Dalgaard L, Pederson O, Astrup A. The association between the val/ala-55 polymorphism of the uncoupling protein 2 gene and exercise efficiency. Int J Obes. 2001;25(4):467–471. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coyle EF, Sidossis LS, Horowitz JF, Beltz JD. Cycling efficiency is related to the percentage of type I muscle fibers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24(7):782–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniels J, Daniels N. Running economy of elite male and elite female runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24(4):483–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dempster P, Aitkens S. A new air displacement method for the determination of human body composition. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27(12):1692–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drinkard BE, Hicks J, Danoff J, Rider LG. Fitness as a determinant of the oxygen uptake/work rate slope in healthy children and children with inflammatory myopathy. Can J App Physiol. 2003;28(6):888–897. doi: 10.1139/h03-063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falls HB, Humphrey LD. Energy Cost of Running and Walking in Young Women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1976;8(1):9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fletcher JR, Esau SP, MacIntosh BR. Economy or running: beyond the measurement of oxygen uptake. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107(6):1918–1922. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00307.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaesser GA, Brooks GA. Muscular Efficiency During Steady-Rate Exercise: Effects of Speed and Work Rate. J Appl Physiol. 1975;38(6):1132–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1975.38.6.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaesser GA, Poole DC. The slow component of oxygen uptake kinetics in humans. Exerc Sports Sci Rev. 1996;24(1):35–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunter GR, Bamman MM, Larson-Meyer DE, Joanisse DR, McCarthy JP, Blandeau TE, Newcomer BR. Inverse relationship between exercise economy and oxidative capacity in muscle. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2005;94(5-6):558–568. doi: 10.1007/s00421-005-1370-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Layec G, Bringard A, Vilmen C, Micallef JP, Le Fur Y, Perrey S, Cozzone PJ, Bendahan D. Does oxidative capacity affect energy cost? An in vivo MR investigation of skeletal muscle energetic. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;106(2):229–242. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1012-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lucia A, Hoyos J, Perez M, Santalla A, Chicharro JL. Inverse relationship between V02max and economy/efficiency in world-class cyclists. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(12):2079–2084. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000039306.92778.DF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malatesta D, Simar S, Dauvilliers Y, Candau R, Borrani F, Prefaut C, Caillaud C. Energy cost of walking and gait instability in healthy 65- and 80-yr-olds. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95(6):2248–2256. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01106.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mallory LA, Scheurmann BW, Hoelting BD, Weiss ML, McAllister RM, Barstow TJ. Influence of peak V02 and muscle fiber type on the efficiency of moderate exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(8):1279–1287. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin PE, Rothstein DE, Larish DD. Effects of Age and Physical Activity Status on the Speed-Aerobic Demand Relationship. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73(1):200–6. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.1.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgensen M, Bagger M, Pedersen PK, Fernstrom M, Sahlin K. Cycling efficiency in humans is related to low UCP3 content and to type I fibres but not to mitochondrial efficiency. J Physiol. 2006;571(3):669–681. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.101691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan DW, Daniels JT. Relationship between V02max and the aerobic demand of running in elite distance runners. Int J Sports Med. 1994;15(7):426–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moseley L, Achten J, Martin JC, Jeukendrup AE. No differences in cycling efficiency between world-class and recreational cyclists. Int J Sports Med. 2004;25(5):374–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-815848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noakes TD. Implications of exercise testing for prediction of athletic performance – a contemporary perspective. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1988;20(4):319–330. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198808000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noakes TD, Tucker R. Inverse relationship between V02max and economy in world-class cyclists. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(6):1083–4. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000128140.85727.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pate RR, Macera CA, Bailey SP, Bartoli WP, Powell KE. Physiological, anthropometric, and training correlates of running economy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24(10):1128–1133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willis WT, Ganley KJ, Herman RM. Fuel oxidation during human walking. Metab Clin Exp. 2005;54(6):793–9. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]