Abstract

Objective To determine whether a general societal preference for prioritising treatment of rare diseases over common ones exists and could provide a justification for accepting higher cost effectiveness thresholds for orphan drugs.

Design Cross sectional survey using a web based questionnaire.

Setting Norway.

Participants Random sample of 1547 Norwegians aged 40-67.

Main outcome measure Choice between funding treatment for a rare disease versus a common disease and how funds should be allocated if it were not possible to treat all patients, for each of two scenarios: identical treatment costs per patient and higher costs for the rare disease. Respondents rated five statements concerning attitudes to equity on a five point Likert scale (5=completely agree).

Results For the equal cost scenario, 11.2% (9.6% to 12.8%) of respondents favoured treating the rare disease, 24.9% (21.7% to 26.0%) the common disease, and 64.9% (62.6% to 67.3%) were indifferent. When the rare disease was four times more costly to treat, the results were, respectively, 7.4% (6.1% to 8.7%), 45.3% (42.8% to 47.8%), and 47.3% (44.8% to 49.8%). Rankings for attitude on a Likert scale indicated strong support for the statements “rare disease patients should have the right to treatment even if more expensive” (mean score 4.5, SD 0.86) and “resources should be used to provide the greatest possible health benefits” (3.9, 1.23).

Conclusions Despite strong general support for statements expressing a desire for equal treatment rights for patients with rare diseases, there was little evidence that a societal preference for rarity exists if treatment of patients with rare diseases is at the expense of treatment of those with common diseases.

Introduction

The expanding list of orphan drugs (medications targeting rare diseases) creates a paradoxical situation for health authorities. The emergence of orphan drugs reflects the success of the 1983 US Orphan Drug Act and similar legislation in other countries in dealing with the lack of market incentives to research and develop treatments for diseases with low prevalence (orphan diseases), defined variously across jurisdictions as 0.18-7.5 per 10 000 population.1 In tackling the costs of drug development and profitability for small target populations, however, legislation on orphan drugs has also increased the monopoly power of producers. As a result orphan drugs are often expensive and rarely meet cost effectiveness criteria for public reimbursement, creating pressure on health officials to exempt orphan drugs from standard cost effectiveness thresholds. The problem is likely to escalate as new treatments are developed for existing orphan diseases and as advances in genetics make it possible to subdivide common diseases, particularly cancers, into distinct categories that can be classified as orphan diseases under existing regulations, each with a tailored orphan treatment (“personalised medicine”). Although it is true that not all orphan drugs are expensive, those that are inexpensive are likely to meet cost effectiveness thresholds, making the need for special funding status a moot point in those cases. A Belgian study2 indicates that few currently authorised orphan drugs meet a €34 000 (£27 900; $43 000) per QALY (quality adjusted life year) cost effectiveness threshold and that the budget impact of orphan drugs is substantial and rising.

Debate about awarding special funding status to orphan drugs—that is, exempting them from standard cost effectiveness thresholds—has focused on both ethical and practical considerations. Proponents of special status often rely on the ethical concept that the seriousness of orphan diseases coupled with limited treatment options requires a “rule of rescue” approach.3 4 They also point to constraints in determining societal valuation of orphan treatments given practical difficulties in obtaining accurate cost effectiveness information among small patient populations,3 5 and to the fact that low prevalence of disease is likely to mean low budgetary impact.3 Some researchers,1 6 7 however, provide compelling arguments for rejecting special status. They argue that standard ethical justifications for awarding special funding status to orphan drugs are not based on “rarity” in itself but rather on other characteristics of orphan diseases, such as severity and no alternative treatment, that could just as easily be applied to common diseases. In addition, they challenge the notion that ignoring cost effectiveness analysis is justifiable if the budgetary impact is small, but also note that while expenditures for individual orphan drugs may be a small part of the health budget, collectively they could represent a much larger share. Ultimately they suggest that only a proved societal preference for treating rare diseases could justify special funding status for orphan drugs.

Currently, little evidence exists on preferences for rarity. A preference for equality in access to treatment might be inferred from existing legislation and government documents. In Norway, for example, the commission on prioritisation in 1987 stipulated that “health care should offer everyone the same opportunity to optimize their health potential,”8 but this does not specifically deal with rare conditions and is potentially inconsistent with language requiring consideration of costs in the Norwegian Patients’ Rights Act of 1999.9 Passage of the US Orphan Drug Act, and comparable regulations in other countries, points to a desire to guarantee that rare diseases are not neglected in pharmaceutical research. Recommendations of the Citizen’s Council of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence in the United Kingdom reflect some consensus among council members that ultra-orphan drugs (prevalence <0.18 per 10 000 population) be considered for special funding on the basis of severity, possibility for improvements in health, and life threatening disease.10 There are, however, also reasons to imagine that a preference for prioritising common diseases could exist. People might reasonably want society to devote resources to the treatment of diseases they believe that they are most likely to experience.

We examined whether a societal preference for rarity, which could justify special funding status for orphan drugs, exists. The primary hypothesis was that in the absence of other differences (for example, disease severity, effectiveness of treatment, or treatment cost), most people will be indifferent to a choice between treating a rare disease and a common one—that is, no societal preference for rarity exists. We also hypothesised that when higher treatment costs for the rare disease are introduced, people will prioritise treatment of the common disease—that is, when confronted with limited resources, people will favour using resources to achieve maximum health gains.

Methods

In August 2009 TNS Gallup Norway surveyed a random sample of 1547 Norwegians aged 40-67, through the internet. To complete the survey rapidly, Gallup invited 6000 people from its active panel of 60 000 randomly recruited people to participate and closed the survey after obtaining the researchers’ requested number of participants. Consequently, the response rate of 26% is biased downwards as not everyone who might have been willing to participate had the opportunity to do so. The sample was relatively representative of the Norwegian population for sex, level of income, and education and was relatively balanced for characteristics of the respondents across the six versions of the survey (table 1).

Table 1.

Respondent characteristics by survey group. Values are percentages unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Survey version on disease severity and benefits of treatment | Total (n=1547) | Norwegian population, target age group* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No information (n=258) | Serious and high (n=256) | Serious and low (n=257) | Moderate and high (n=258) | Moderate and low (n=260) | Serious and high, fixed funds (n=258) | |||

| Men | 54.3 | 55.9 | 53.3 | 47.7 | 54.6 | 54.3 | 53.3 | 50.9 |

| Women | 45.7 | 44.1 | 46.7 | 52.3 | 45.4 | 45.7 | 46.8 | 49.1 |

| Mean age (years) | 51 | 52 | 53 | 52 | 53 | 52 | 52 | 52.7 |

| Marital status: | ||||||||

| Married or registered partners | 62.7 | 64.2 | 60.7 | 69.0 | 61.8 | 68.0 | 64.4 | 61.9 |

| Living together | 10.0 | 12.9 | 14.8 | 10.7 | 10.1 | 12.3 | 11.8 | 10.1 |

| Unmarried | 13.2 | 7.9 | 11.2 | 6.9 | 10.7 | 10.1 | 10.0 | 9.3 |

| Separated, divorced, widowed | 14.2 | 15.0 | 13.3 | 13.4 | 17.3 | 9.7 | 13.8 | 18.7 |

| Highest level of education: | ||||||||

| <Secondary school/trade school | 30.2 | 28.1 | 21.2 | 24.5 | 26.8 | 26.8 | 26.3 | 22.4 |

| Secondary school | 44.8 | 42.1 | 50.3 | 46.4 | 49.6 | 47.0 | 46.7 | 48.4 |

| University (≤4 years) | 15.2 | 15.5 | 17.0 | 17.3 | 14.4 | 15.3 | 15.7 | 21.3 |

| University (>4 years) | 9.8 | 14.4 | 11.5 | 11.8 | 9.2 | 11.0 | 11.3 | 8.0 |

| Gross personal income (kroner)†: | ||||||||

| <200 000 | 11.8 | 7.4 | 11.8 | 9.9 | 11.0 | 10.1 | 10.3 | 15.1 |

| 200 000 to 399 999 | 51.2 | 53.5 | 53.9 | 56.8 | 48.4 | 51.6 | 52.5 | 42.3 |

| 400 000 to 599 999 | 27.2 | 28.8 | 24.9 | 25.9 | 32.7 | 28.6 | 28.1 | 27.3 |

| 600 000 to 799 999 | 5.3 | 7.0 | 7.6 | 4.9 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 8.0 |

| ≥800 000 | 4.5 | 3.3 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 7.4 |

Kr1 (£0.12; $0.16).

*Data from Statistics Norway, 2008-9.

†Based on 1479 respondents. Sixty eight (4.4%) chose not to reveal personal income.

Survey design

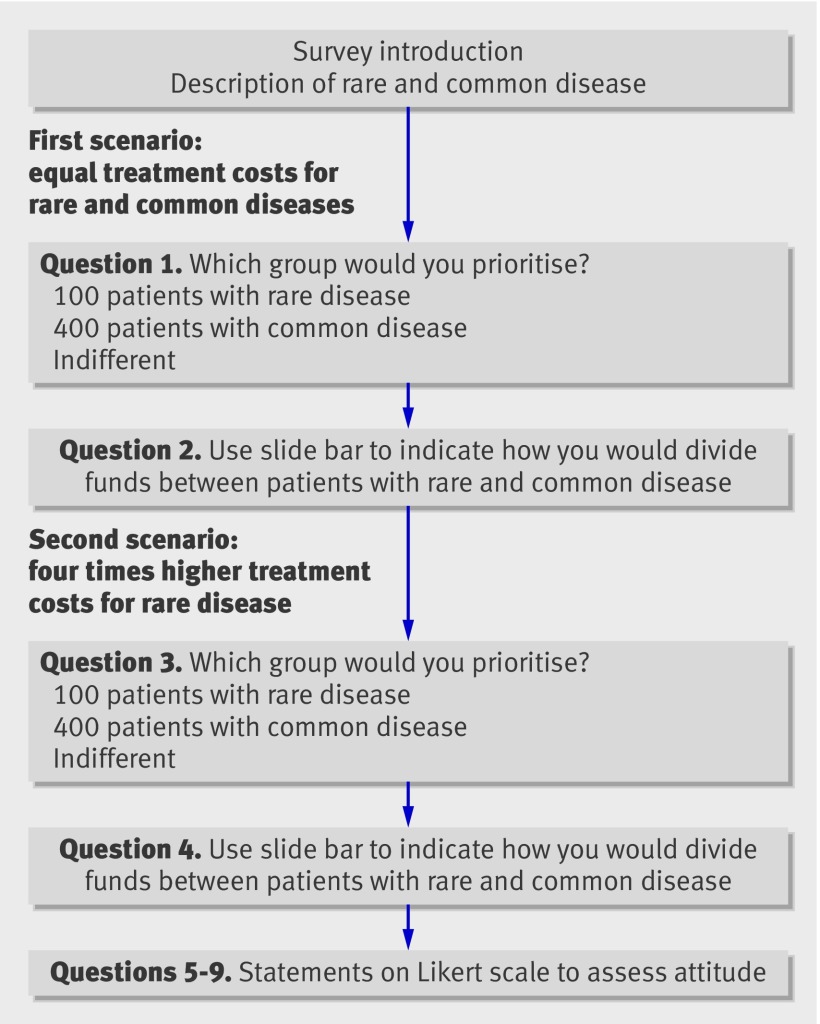

Figure 1 presents the basic structure of the survey (see web extra for the full text). The survey began with an introduction to the problem and brief descriptions of a rare and a common disease, including prevalence, severity of the disease, and expected benefits of treatment. The diseases were described as identical with the exception of prevalence, with 100 cases defined as rare and 10 000 as common in Norway (population 4.8 million). Respondents were told that extra funds were available that could be used to treat one of the disease groups and were presented with two different scenarios: identical treatment costs per patient for each disease and four times higher costs for the rare disease.1 For each scenario respondents were asked to decide which group to prioritise for treatment (rare, common, indifferent) and then to indicate how they would allocate the funds between the disease groups if it were possible to do so. The question on allocation was completed by use of an accompanying slide bar marked with the numbers of patients in each disease group who would receive treatment under different allocations of funds. The first scenario was designed to elicit a preference for rarity in itself; in the absence of any other differences between the two diseases respondents would be expected to express no preference for treating patients with the rare disease compared with treating those with the common disease. The second scenario, in which the treatment for the rare disease was more costly, examined preferences for rarity in the context of a more realistic situation in which the rare disease was more costly to treat. The survey concluded by asking respondents to rate statements about equity and efficient use of resources on a five point Likert scale (1=completely disagree, 5=completely agree). The final format of the survey included refinements based on a pilot survey of 25 people.

Fig 1 Summary of survey questionnaire

Respondents were randomised (table 2) to either no information or combinations of information on disease severity (severe v moderate) and expected benefits of treatment (high v low). Severity and benefits of treatment were presented using the EQ5-D11 health state descriptions for mobility and pain. In five versions of the survey the choices were described in a context of how to allocate additional funds provided by the government (extra funds scenario), whereas in the sixth version the choices were framed as whether to treat patients with rare diseases by reducing the number of patients currently treated for common diseases (fixed funds scenario).

Table 2.

Randomisation of respondents in survey

| Scenario (disease severity, treatment benefit) | Funding scenario | No of respondents (n=1547) |

|---|---|---|

| No information | Extra funds | 258 |

| Severe disease, high benefit | Extra funds | 256 |

| Severe disease, low benefit | Extra funds | 257 |

| Moderate disease, high benefit | Extra funds | 258 |

| Moderate disease, low benefit | Extra funds | 260 |

| Severe disease, high benefit | Fixed funds | 258 |

Results

General preferences

Rankings on attitude to equity using a five point Likert scale (table 3) indicated strong support for the statements that “all individuals should have equal access to health care regardless of the cost” (mean score 4.5, SD 0.98) and “patients with rare diseases should have the right to treatment even if treatment is more expensive” (4.5, 0.86). Respondents also expressed agreement with the potentially contradictory statement, “health authorities should use resources to provide the greatest possible health benefits” (3.9, 1.23).

Table 3.

Responses of 1547 respondents to three statements assessing attitudes on a five point Likert scale. Values are percentages (numbers)

| Response* | All should have equal access to health care regardless of costs | Patients with rare diseases should have same right to treatment as others even if more expensive | Health authorities should use funds where they provide largest possible health benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.9 (45) | 1.6 (25) | 6.8 (105) |

| 2 | 3.8 (59) | 2.3 (35) | 6.1 (94) |

| 3 | 6.1 (94) | 7.0 (108) | 19.0 (294) |

| 4 | 13.8 (214) | 20.8 (321) | 27.3 (423) |

| 5 | 72.7 (1124) | 67.4 (1042) | 38.9 (601) |

| Don’t know | 0.7 (11) | 1.0 (16) | 1.9 (30) |

*Response on five point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree).

Preferences under trade-off conditions

The first survey question requiring a trade-off between different patient groups asked respondents whether they would use newly available funds to treat 100 patients with a rare disease or 100 patients with a common disease, a scenario that implies equal treatment costs for the two diseases. An additional implication is that the real cost of treating one patient with the rare disease is the lost opportunity to treat another patient with the common disease. For the entire sample of 1547 respondents, 173 (11.2%, 95% confidence interval 9.6% to 12.8%) favoured treating the rare disease, 369 (23.8%, 21.7% to 26.0%) the common disease, and 1005 (65.0%, 62.6% to 67.3%) were indifferent (table 4). Among the 1289 respondents randomised to survey scenarios with an extra funds frame, 132 (10.2%, 8.6% to 11.9%) favoured treating the rare disease, 257 (19.9%, 17.8% to 22.1%) the common disease, and 900 (69.8%, 67.3% to 72.3%) were indifferent. The association between the expressed preference and the amount of information provided to respondents on the severity of the disease and benefits of treatment was significant (χ2=20.0, P<0.001; table 4, scenario of no information compared with scenarios of serious and moderate disease severity with high and low benefits). Changing the frame from extra funds to fixed funds (serious disease and high benefits compared with the same scenario but fixed funds) to emphasise a potential loss of health benefits to one group by noting that the 100 patients with rare disease could be treated only by eliminating treatment for 100 patients currently being treated for common disease, also had a significant effect on responses (χ2=70.5, P<0.001). Multinomial logistic regression (see web extra) confirmed these results.

Table 4.

Preferences of respondents for allocating resources when treatment costs are equal between rare and common disease, by survey scenario

| Scenario | No randomised to scenario | % (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prioritise rare disease | Prioritise common disease | Indifferent | ||

| All extra funds scenarios | 1289 | 10.2 (8.6 to 11.9) | 19.9 (17.8 to 22.1) | 69.8 (67.3 to 72.3) |

| Extra funds (no information) | 258 | 15.9 (11.4 to 20.4) | 25.2 (19.9 to 30.5) | 58.9 (52.9 to 64.9) |

| Extra funds (disease severity and treatment benefit scenarios) | 1031 | 8.8 (7.1 to 10.6) | 18.6 (16.2 to 21.0) | 72.5 (69.8 to 75.3) |

| Severe disease, high benefit | 256 | 7.8 (4.5 to 11.1) | 15.2 (10.8 to 19.6) | 77.0 (71.8 to 82.1) |

| Severe disease, low benefit | 257 | 9.7 (5.1 to 13.4) | 21.0 (16.0 to 26.0) | 69.3 (63.6 to 74.9) |

| Moderate disease, high benefit | 258 | 9.3 (5.7 to 12.9) | 16.7 (12.1 to 21.2) | 74.0 (68.7 to 79.4) |

| Moderate disease, low benefit | 260 | 8.5 (5.1 to 11.9) | 21.5 (16.4 to 26.5) | 70.0 (64.4 to 76.6) |

| Fixed funds (severe disease, high benefit) | 258 | 15.9 (11.4 to 20.4) | 43.4 (37.3 to 49.5) | 40.7 (34.7 to 46.7) |

| All scenarios | 1547 | 11.2 (9.6 to 12.8) | 23.8 (21.7 to 26.0) | 65.0 (62.6 to 67.3) |

Whether the preference for rarity was sensitive to the number of patients with common disease specified in the trade-off was examined by asking respondents to imagine that the extra funding could provide treatment for 100 patients with rare disease or 400 patients with common disease, implying that the rare disease was four times more costly to treat than the common disease (table 5). In this case, 114 (7.4%, 6.1% to 8.7%) respondents favoured treating the rare disease, a decline from 11.2% (McNemar test 35.2, P<0.001) in the equal cost scenario, whereas 701 (45.3%, 42.8% to 47.8%) favoured the common disease and 732 (47.3%, 44.8% to 49.8%) were indifferent.

Table 5.

Respondents’ preferences for allocating resources when treatment costs are four times greater for rare disease compared with common disease, by survey scenario

| Scenario | No randomised to scenario | % (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prioritise rare disease | Prioritise common disease | Indifferent | ||

| No information | 258 | 13.2 (9.0 to 17.3) | 33.7 (27.9 to 39.5) | 53.1 (46.0 to 59.2) |

| Severe disease, high benefit | 256 | 7.0 (3.9 to 10.2) | 45.3 (39.2 to 51.4) | 47.7 (41.5 to 53.8) |

| Severe disease, low benefit | 257 | 5.8 (3.0 to 8.7) | 42.0 (36.0 to 48.1) | 52.1 (46.0 to 58.3) |

| Moderate disease, high benefit | 258 | 7.4 (4.2 to 10.6) | 45.3 (39.2 to 51.4) | 47.3 (41.2 to 53.4) |

| Moderate disease, low benefit | 260 | 6.9 (3.8 to 10.0) | 45.0 (38.9 to 51.1) | 48.1 (42.0 to 54.2) |

| Fixed funds (severe disease, high benefit) | 258 | 3.9 (1.5 to 6.2) | 60.5 (54.5 to 66.4) | 35.7 (29.8 to 41.5) |

| All scenarios | 1547 | 7.4 (6.1 to 8.7) | 45.3 (42.8 to47.8) | 47.3 (44.8 to 49.8) |

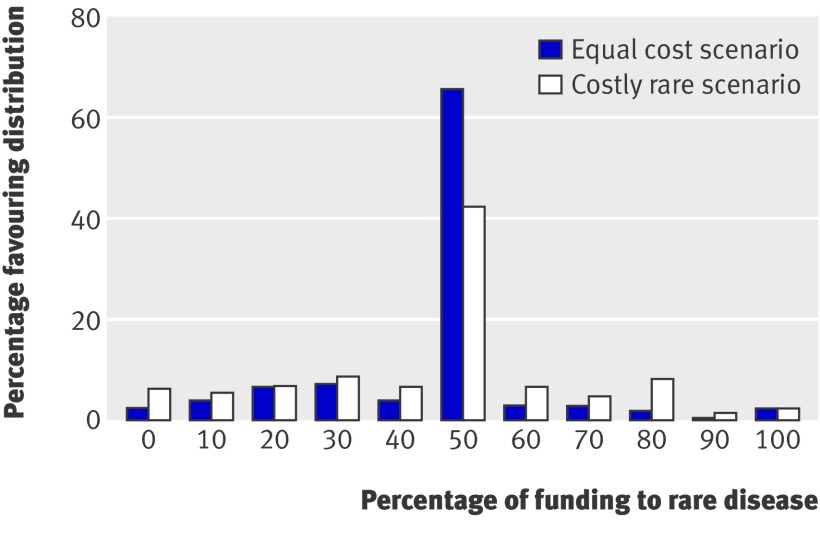

Figure 2 shows how respondents chose to allocate resources when offered the opportunity to treat some patients from each disease group. In the equal cost scenario 65.4% (n=1012) favoured dividing the funds equally, 24.1% (n=373) favoured allocating the larger share to the common disease, and 10.5% (n=162) favoured allocating most to the rare disease. These results can also be used to examine the intensity of preference by assigning a preference weight for each respondent based on the number of patients in the preferred treatment group and then summing across people. With equal treatment costs, interpretation of the weighted results is straightforward; a preferred allocation of 40 patients with the rare disease and 60 with the common disease carries a weight of 60 for the common disease and indicates a preference both for treating 60 patients with the common disease and for spending 60% of resources on treating the common disease. For the equal cost scenario, the ratio of weighted preferences for the common to the rare disease was 2.3, consistent with the unweighted results. In the costly rare scenario, 42.3% (n=655) of respondents favoured dividing funds equally, 34.2% (n=529) favoured allocating most to the common disease, and 23.5% (n=363) favoured allocating most to the rare disease. Interpreting choices of allocation in this case is more complicated because dividing the available funds equally means treating 200 patients with the common disease and 50 patients with the rare disease rather than equal numbers of patients, an outcome that would occur if 80% of funds were devoted to the rare disease. Only 3.6% (n=55) of respondents favoured allocating more than 80% of funds to the rare disease.

Fig 2 Preferences for allocation of resources when faced with choice to treat some patients with rare disease and some with common disease

Discussion

The results of this cross sectional survey support our primary hypothesis that, in the absence of other differences, no societal preference for rarity exists. Faced with the choice between treating 100 patients with a rare disease compared with treating 100 patients with a common disease, most respondents were, as expected, indifferent regardless of the amount of information provided or the framing of the question. A few prioritised the rare disease but twice as many favoured the common disease, a result that is consistent with prioritising the disease that someone is more likely to experience. If societal preferences are deemed to be represented by a simple majority, it is clear that no societal preference for rarity exists. It is possible that a societal preference should also reflect the intensity of individual preferences. We considered this possibility by examining weighted preferences when respondents allocated funds to both disease groups, and again we found no societal preference for rarity.

The results concerning our second hypothesis, that people will prioritise the common disease if the rare disease is costlier to treat, are much less convincing. When confronted with a scenario in which the rare disease was four times more costly to treat, the number of respondents who expressed a preference for treating the rare disease declined and many who were previously indifferent moved to favouring treatment of the common disease. This provides some support for the hypothesis. However, a large number of people (47.3%) expressed indifference when asked to choose between treating patients with the rare disease and those with the common disease, and when offered the opportunity favoured dividing the funds equally between the two disease groups (42.3%).

One possible interpretation of this result is that it reflects a preference for the rare disease, thus contradicting our hypothesis. The economic interpretation of indifference in this case is that the value of treating one patient with the rare disease is viewed as equivalent to the value of treating four patients with the common disease, indicating that treating a patient with the rare disease is preferred to treating a patient with the common disease. We are reluctant to accept this interpretation as indication of a societal preference for rarity for several reasons. Firstly, it could be a manifestation of aversion to choice12; people are known to avoid making unpleasant decisions, actively “deciding not to decide.” Secondly, it might be an indication of a visual central tendency bias in the results using the slide bar; picking the middle option is an easy choice when one is uncertain. Furthermore, given that the four to one cost differential between orphan and common treatments implied in the survey is significantly lower than the cost difference based on actual prices of orphan drugs,2 it is likely that support for rarity would diminish even more in the context of more realistic treatment costs.

A more likely interpretation of the results in the costly rare scenario is that they reflect the confounding effect of a general concern for fairness in the allocation of health resources, as opposed to a specific preference for prioritising rare diseases over common ones. For example, two studies13 14 found evidence that people place greater importance on equity than cost effectiveness in allocating scarce resources. In practice, unfortunately, it is difficult to disentangle a specific preference for rarity from a more general preference for fairness.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Our study benefits from being, to the best of our knowledge, the first to examine the issue of preferences for rarity, and as such provides important information for policy makers about a controversial topic that is likely to become increasingly important. In addition, our primary result, that in the absence of other differences there is no societal preference for rarity, is straightforward and unambiguous. The survey design expressly took into account several methodological issues that could have had an impact on the results: the method used to elicit preferences may influence responses—for example, people may express support for general statements concerning equality of treatment possibilities but may display other preferences when confronted with situations involving trade-offs; people may be influenced by framing of the problem—for example, they may be likely to prefer avoiding loss to experiencing an equivalent gain (loss aversion)15; and the amount of information provided about the severity of disease or benefits of treatment may have an impact (with no information respondents are likely to make their own assumptions about severity or treatment benefits, clouding the interpretation of their responses).

Our study does, however, have some limitations. Firstly, and most importantly, it does not provide a clear sense of the meaning respondents attributed to the term “indifferent” or to what lay behind the slide bar decisions in the scenario of treating costly rare disease, making it difficult to interpret the results in this case. Lacking this information, there is no way to distinguish between a possible specific preference for rarity and a general preference for fairness when the rare disease was four times more costly than the common disease. Secondly, a potential central tendency bias is inherent in the slide bar method of allocating resources between the diseases. Thirdly, as with other stated preference exercises, the hypothetical nature of the questions may reduce the reliability of the responses. Fourthly, it is possible that our results are only representative of Norwegian values and would not reflect preferences in other countries. Finally, the survey methods could have resulted in an over-representation of respondents with strong views, although it is not clear what effect this would have had on the results. The first four limitations constitute areas for future research.

Conclusions and policy implications

We see little compelling evidence in our survey results to support the existence of a societal preference for rarity in itself, a finding that supports the view that treatments for rare disease should not be exempt from standard considerations of cost effectiveness. There may, however, be other unexplored ethical reasons to favour special funding status for orphan drugs; majority opinion is not necessarily a good measure of what is ethical. Our findings do suggest that if policy makers are to take the difficult and possibly unpopular decision to evaluate orphan drugs on the same basis as treatments for common diseases, they need to defend their choice with clear reference to the opportunity cost (as measured by numbers of patients with common diseases who will go untreated) of ignoring standard cost effectiveness criteria.

What is already known on this topic

Drugs for rare diseases (orphan drugs) seldom meet standard cost effectiveness thresholds used to evaluate new drugs

Some studies suggest that only a societal preference for rarity would justify granting exceptions to cost effectiveness thresholds for orphan drugs

To date, no empirical research has been carried out in this area

What this study adds

No evidence was found of a societal preference for rarity that would justify ignoring cost effectiveness considerations

We thank Arvid Heiberg for providing information on several rare diseases, Erik Nord for discussions on the design of the survey, and the two reviewers for their comments during the review process.

Contributors: ASD designed the study, analysed the data, and wrote the paper. DGH, JAO, SG, and ISK contributed to the study design and interpretation of results. ISK conceived the study. All authors approved the final version of the paper. ASD is the guarantor.

Funding: This research was supported by grants from the Norwegian Research Council and the health economics research programme, HERO, at the University of Oslo.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and all authors want to declare (1) Financial support for the submitted work from the Norwegian Research Council and the Health Economics Research Programme (HERO) at the University of Oslo. ISK (2) has received gifts, travel funds, honorariums, consultancy fees or salary from a wide range of public institutions, not for profit organisations or for profit organisations that may have an interest in orphan drug issues. The other authors declare no interests under (2), and all authors declare that they have (3) No spouses, partners, or children with relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; (4) No non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: Survey data are available from the corresponding author on request.

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;341:c4715

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Full text of survey

Results of multinomial logistic regression

References

- 1.McCabe C, Claxton K, Tsuchiya A. Orphan drugs and the NHS: should we value rarity? BMJ 2005;331:1016-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denis A, Mergaert L, Fostier C, Cleemput I, Simoens S. Budget impact analysis of orphan drugs in Belgium: estimates from 2008 to 2013. J Med Econ 2010; published online 18 May. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Hughes DA, Tunnage B, Yeo ST. Drugs for exceptionally rare diseases: do they deserve special status for funding? QJM 2005;98:829-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKie J, Richardson J. The rule of rescue. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:2407-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drummond MF, Wilson DA, Kanavos P, Ubel P, Rovira J. Assessing the economic challenges posed by orphan drugs. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2007;23:36-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCabe C, Tsuchiya A, Claxton K, Raftery J. Orphan drugs revisited. QJM 2006;99:341-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCabe C, Tsuchiya A, Claxton K, Raftery J. Assessing the economic challenges posed by orphan drugs: a comment on Drummond et al. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2007;23:397-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helse—OG Omsorgsdepartementet. NOU 1987:23. Retningslinjer for prioriteringer innen norsk helsetjeneste.1987. www.regjeringen.no/nb/dep/hod/dok/nouer/1999/nou-1999-2/4/2.html?id=350994.

- 9.Norwegian Government. Patients’ Rights Act. 1999. www.ub.uio.no/ujur/ulovdata/lov-19990702-063-eng.pdf.

- 10.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Citizens Council report: ultra orphan drugs. 2004. www.nice.org.uk/niceMedia/pdf/Citizens_Council_Ultraorphan.pdf.

- 11.EQ-5D. EuroQol. 2010. www.euroqol.org/.

- 12.Tversky A, Shafir E. Choice under conflict: the dynamics of deferred decision. Psychological Science 1992;3:358-61. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nord E, Richardson J, Street A, Kuhse H, Singer P. Maximizing health benefits vs egalitarianism: an Australian survey of health issues. Soc Sci Med 1995;41:1429-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ubel PA, DeKay ML, Baron J, Asch DA. Cost-effectiveness analysis in a setting of budget constraints—is it equitable? N Engl J Med 1996;334:1174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 1981;211:453-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Full text of survey

Results of multinomial logistic regression