Abstract

Background

Epididymo-orchitis is a common urological presentation in men but recent incidence data are lacking. Guidelines for management recommend detailed investigation and treatment for sexually transmitted pathogens, such as Chlamydia trachomatis. Data from secondary care indicate that these guidelines are poorly followed. It is not known how epididymo-orchitis is managed in UK general practice.

Aim

To estimate the incidence of cases of epididymo-orchitis seen in UK general practice, and to describe their management.

Design of study

Cohort study.

Setting

UK general practices contributing to the General Practice Research Database (GPRD).

Method

Men, aged 15–60 years, consulting with a first episode of epididymo-orchitis between 30 June 2003 and 30 June 2008 were identified. All records within 28 days either side of the diagnosis date were analysed to describe the management of these cases (including location) and to compare this management with guidelines.

Results

A total of 12 615 patients with a first episode of epididymo-orchitis were identified. The incidence was highest in 2004–2005 (25/10 000) and declined in the later years of the study. Fifty-seven per cent (6943) of patients were managed entirely within general practice. Of these, over 92% received an antibiotic, with ciprofloxacin being the most common one prescribed. Only 18% received a prescription for doxycycline. Most men, including those under 35 years, had no investigation recorded and fewer than 3% had a test for chlamydia.

Conclusion

These results indicate low rates of specific testing and treatment for sexually transmitted infections in males who attend general practice with symptoms of epididymo-orchitis. There is a need for further research to understand the pattern of care delivered in general practice.

Keywords: chlamydia, electronic health records, epididymitis, incidence, primary health care

INTRODUCTION

Acute epididymitis, without or with testicular involvement (here described as epididymo-orchitis), is a common urological condition in men, presenting with unilateral testicular pain and swelling. Recent epidemiological data are lacking, but a previous estimate from UK general practice suggested incidence rates of 40/10 000 person-years,1 and outpatient data from the US report epididymo-orchitis as the fifth most common urological diagnosis between the ages of 18 and 50 years.2

Existing guidelines are based on a clinical consensus that in men under 35 years, epididymo-orchitis is most commonly caused by a sexually transmitted pathogen such as Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae.3–7 In older men, the infection is more likely to be due to non-sexually transmitted enteric Gram-negative organisms.8 The extent of idiopathic or sterile cases is unclear, as some of the literature predates the identification of C. trachomatis, but no infection is identified in a sizeable proportion (46%) of cases.9 Novel organisms, such as Mycoplasma genitalium, which are not included in testing regimes, may be involved in such cases. The data underlying this conventional divide at 35 years may, however, be questioned, as they are based on small studies in selected populations.3–7 Guidelines from the US and UK suggest a detailed testing schedule, involving C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae, urethral swabs or first-void urine culture, and midstream urinalysis (MSU), followed by antibiotics as indicated by history, with doxycycline for likely C. trachomatis infections, ceftriaxone/ciprofloxacin followed by doxycycline for N. gonorrhoeae infections, and ofloxacin/ciprofloxacin for enteric organisms.8,10

How this fits in

Epididymo-orchitis is a common urological presentation in general practice, which is often related to sexually transmitted infection in younger men. Guidelines for management exist but it is not known how these are followed by GPs. The results of this study, from an anonymised database of primary care electronic records, indicate investigation and treatment that does not address sexually transmitted infection in the majority of men. Further research is required to understand why GPs are not following recommended practice.

Effective treatment and management of epididymo-orchitis is important for clinical and public health reasons. There are clinical concerns about long-term sequelae including infertility, prostatitis, and strictures.11–14 Cases related to sexually transmitted infection (STI) present opportunities to screen for infection and to offer treatment, and for partner notification, which should not be missed. The National Strategy for Sexual Health and HIV has, since 2001, recommended a greater role for primary care providers in the care of STIs.15

The sparse literature on the management of epididymo-orchitis raises concerns. A survey of UK urologists indicated low compliance with guidelines,16 whereas a survey of genitourinary medicine (GUM) departments reported near-complete adherence.9 Data from a US university hospital also suggest low rates of testing for STIs.17 Although some cases of epididymo-orchitis may present to GUM clinics or direct to an emergency department, most men will attend their GP first. Simms et al reported high attendance rates for epididymo-orchitis in UK primary care.1 No studies describing GP management of epididymo-orchitis were identified. There is a need for updated descriptive data using real-time patient records to record the incidence of the disorder and to describe management and hence to inform continuing education.

The current study aimed to estimate the incidence of epididymo-orchitis in primary care between 2003 and 2008. It also aimed to describe the management of patients with this condition, within the practice and beyond, and to assess its adequacy in relation to existing guidelines, including associations between management and various patient and practice factors.

METHOD

Target population

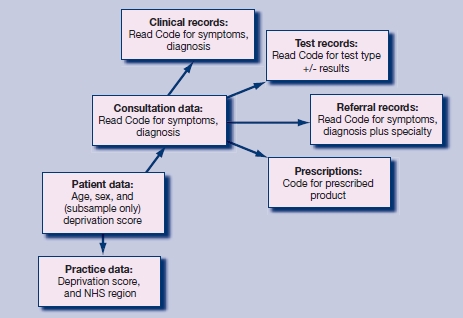

The General Practice Research Database (GPRD) is an electronic database of anonymised longitudinal patient records from general practice.18 Established in 1987, it is a UK-wide dataset covering 5.5% of the population, with data from 460 practices, and is broadly representative of the UK population. There are 3.5 million currently active patients. Records are derived from the GP computer system (VISION) and contain complete prescribing and coded diagnostic and clinical information held in different record tables (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of GPRD database.

Many laboratory results are now imported directly into the system, and letters received from hospitals will be logged with either full text included or the diagnoses coded. Patient-level data include age and sex and, in 200 of 460 practices (approximately 40%), a Townsend deprivation index score based on the postcode of the patient. Practice-level data include a deprivation index score based on the postcode of the practice and the NHS region in which the practice is based.

Study population

The study period was from 30 June 2003 to 30 June 2008 and the source population was all permanently registered male patients in practices meeting GPRD quality standards. The study population consisted of all men with a first coded diagnosis of epididymo-orchitis within the study period, who were aged 15-60 years at the time of diagnosis. Code lists used for the definition of cases are listed in Appendix 1. Men with a coded diagnosis relating to vasectomy, sterilisation, or instrumentation of the urinary tract 60 days before to 28 days after the date of the epididymo-orchitis code were excluded, as they might have an obvious precipitating cause and hence their management might reasonably not folow guidelines. Men over 60 years were excluded because previous work has found a large proportion of catheter-associated infections in this age group.19 Similarly, the vast majority of boys under 15 years will not be sexually active and hence will have low C. trachomatis positivity. Appropriate management for these cases could reasonably not follow recommended guidelines and so they were not included in the study.

If multiple diagnostic codes for epididymo-orchitis were recorded for an individual, the date of the first diagnostic code was used as the index date. Analyses were restricted to records in the period 28 days before and after the index date. Cases where the index date was within 28 days of the start or end of the registration at the practice were excluded from descriptions of management.

Description of management

Testing. A specific chlamydia test was considered to have been carried out if the record contained either a code for a test (for example, ‘chlamydia antigen test’) or a diagnosis of genital C. trachomatis infection (for example, ‘chlamydial epididymitis’ or ‘chlamydial infection of the lower genitourinary tract’). Codes were identified for tests for N. gonorrhoeae. Non-specific microbial tests were considered to have been carried out if there was a code for either appropriate swab (for example, ‘urethral swab’) or a test such as microscopy, culture and sensitivities with no location given. Codes for bacterial urine testing, including dipstick tests and MSU, were also identified.

Treatment. Variables based on prescription records were created for antibiotic treatments:

antibiotics recommended for epididymo-orchitis: ofloxacin, doxycycline, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin;8,10 code lists were drawn up using drug substance name, and included all formulations except for inappropriate topical preparations;

antibiotics suitable for treatment of urinary tract infections (UTIs); code lists included all cephalosporins (British National Formulary (BNF) chapter heading 050102) and amoxicillin, trimethoprim, and nitrofurantoin; and

all antibiotics: based on BNF heading 0501.

Dosage and duration of use were not assessed.

Location of care. It was considered that a patient had received care for epididymo-orchitis in another healthcare setting if either of the following conditions were met:

a diagnostic code for the condition or a suggestive symptom code (for example, ‘testicular swelling’) within the referral record; or

a code anywhere in the records indicating care elsewhere (for example, ‘referral to emergency department’, ‘seen in GUM clinic’). This category also included less specific terms such as ‘discharge summary’ or ‘letter from specialist’.

If there was no evidence of care elsewhere and there was some evidence of any treatment or testing within the practice, the case was considered to have been managed within the practice only. Men with no evidence of either any management in practice or care elsewhere (that is, where the record had just a diagnostic code) were considered a separate group, due to concerns about completeness of recording, particularly related to care elsewhere. Analyses of management were restricted to males who were managed within the practice only. It did not seem appropriate to assess quality of care if important parts of the care may have been delivered outside the practice and hence not necessarily recorded there.

Statistical analysis

Data were prepared using Stata (version 10; Statacorp LP, Texas). Calendar years were defined as mid-years from 30 June, so that year 2003 covered 30 June 2003 to 29 June 2004, and so on. Incidence rates were calculated in specific age groups and event years by dividing the number of cases by the appropriate denominator. Age-standardised rates for all ages combined were then obtained by applying these rates to the European standard population. Differences in incidence rates over time and age groups were assessed using Poisson regression. Analyses of management calculated the proportion of patients with various management markers across years and age groups. Logistic regression models investigated factors associated with optimal management.

A series of sensitivity analyses were performed, extending the window for analysis of management from 28 to 42, 60, and 90 days either side of the index date, to assess whether relevant data were being missed by using the 28-day window. Men with diagnostic codes for orchitis only, with no mention of epididymal involvement, were also excluded as appropriate management of viral orchitis would differ.

RESULTS

Target population and incidence

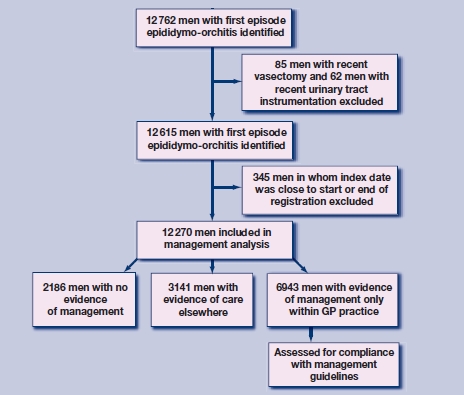

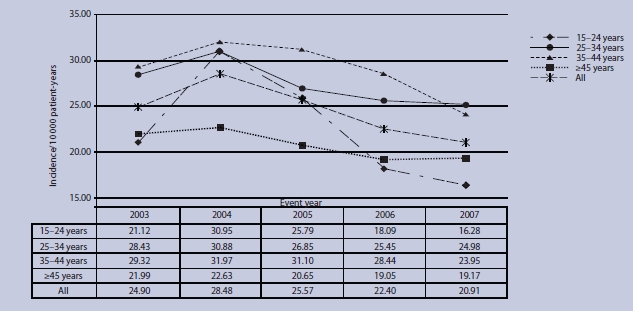

Figure 2 summarises the identification and exclusion of cases. A total of 12 615 males with first diagnosis of epididymo-orchitis were included in incidence analyses; median age was 37 years (interquartile range 28–46 years). Age-standardised incidence of epididymo-orchitis was highest in 2004 (28/10 000 male person-years) and then declined progressively to 21/10 000 male person-years in 2007 (P<0.001) (Figure 3). This decline was greatest in younger age groups (P-value for interaction term for age less than 35 years with event year = 0.09). Incidence in males over 45 years was stable during the study period at approximately 20/10 000 person-years.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of study: patient identification and exclusions.

Figure 3.

Incidence of first episode of epididymo-orchitis in primary care: 2003–2007.

Management of cases

Analyses of management included 12 270 males, of which 4955 were aged under 35 years (Table 1); 57% of men (6943) were managed entirely within the practice, and 26% (3141) had evidence of receiving care elsewhere; 18% of cases (2186) had no evidence either of management within practice or care elsewhere. Of the 6943 cases managed by primary care (Table 2), 92% received an antibiotic prescription; 56% received an antibiotic recommended for epididymo-orchitis, 18% received doxycycline, and 29% received an antibiotic indicated for a UTI but not for epididymo-orchitis. Recorded investigations were uncommon, with fewer than 3% of men having a C. trachomatis test recorded and only 12% having had any microbial investigation for urethritis. Testing for N. gonorrhoeae was extremely unusual. Urinalysis, including MSU, was the most common form of testing (22%) but the majority of men had no test or result coded.

Table 1.

Location of management of epididymo-orchitis cases seen in primary care.

| Aged <35 years, n (%) | Aged ≥35 years, n (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Evidence of care elsewhere | Managed only in practice | No evidence of management | n | Evidence of care elsewhere | Managed only in practice | No evidence of management | |

| 2003 | 973 | 203 (20.9) | 551 (56.6) | 219(22.5) | 1484 | 291 (19.6) | 889 (59.9) | 304 (20.5) |

| 2004 | 1232 | 321 (26.1) | 642 (52.1) | 269 (21.8) | 1609 | 356 (22.1) | 954 (59.3) | 299(18.6) |

| 2005 | 1060 | 276 (26.0) | 584 (55.1) | 200(18.9) | 1533 | 431 (28.1) | 852 (55.6) | 250(16.3) |

| 2006 | 871 | 230 (26.4) | 495 (56.8) | 146(16.8) | 1416 | 388 (27.4) | 800 (56.5) | 228(16.1) |

| 2007 | 819 | 244 (29.8) | 454 (55.4) | 121 (14.8) | 1273 | 401 (31.5) | 722 (56.7) | 150(11.8) |

| P-value for trend | <0.001 | 0.60 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.02 | < 0.001 | ||

| Total | 4955 | 1274 (25.7) | 2726 (55.0) | 955(19.3) | 7315 | 1867 (25.5) | 4217 (57.7) | 1231 (16.8) |

Table 2.

Treatment and investigation of cases managed within practice only.

| n(% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All, n = 6943 | Aged <35 years, n = 2726 | Aged ≥35 years, n = 4217 | P-value for difference between age groups | |

| Treatment | ||||

| Antibiotic recommended for Chlamydia trachomatis | ||||

| Doxycycline | 1270 (18.3) | 541 (19.9) | 729 (17.3) | 0.007 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 2511 (36.2) | 941 (34.5) | 1570 (37.2) | 0.022 |

| Ofloxacin | 224 (3.2) | 88 (3.2) | 136 (3.2) | 0.990 |

| Ceftriaxone | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Any one of the abovea | 3859 (55.6) | 1514 (55.5) | 2345 (55.6) | 0.980 |

| Other UTI antibioticb | 2045 (29.4) | 796 (28.9) | 1249 (29.6) | 0.720 |

| Any other antibioticb | 508 (7.3) | 212 (7.8) | 296 (7.0) | 0.230 |

| Any antibiotica | 6412 (92.4) | 2522 (92.5) | 3890 (92.3) | 0.640 |

| Investigation | ||||

| Chlamydia test | 180 (2.6) | 120 (4.4) | 60 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae test | 4 (0.06) | 3 (0.1) | 1 (0.02) | 0.146 |

| Any microbial test | 649 (9.4) | 284 (10.4) | 365 (8.7) | 0.014 |

| Urine testc | 1507 (21.7) | 547 (20.1) | 960 (22.7) | 0.008 |

Total of rows above.

Excludes all antibiotics in preceding rows of tables.

Bacterial urine testing, including dipstick tests and midstream urinalysis. UTI = urinary tract infection.

There was some evidence that men under 35 years were managed differently from older men, although the differences were small. Younger men were more likely to have no evidence of any management (19.2% versus 16.8%, P<0.001) and, correspondingly, were less likely to be managed only within the GP practice (55.2% versus 57.7%, P = 0.003). Of those managed by GPs, younger men were more likely to be prescribed doxycycline and have a C. trachomatis or microbial test than older men, and less likely to be treated or investigated for a UTI.

The proportion of patients managed within general practice was stable across the study period but there was a fall in the proportion of cases with no evidence of management in both age bands, and this was matched by an increase in the proportion with evidence of care elsewhere (Table 1). When trends in treatment and investigation over the study period were examined (not shown in tables), the use of ciprofloxacin increased over time, rising from 31% to 44% in both age bands (P<0.001), but there was no evidence of an increase in doxycycline prescriptions or C. trachomatis testing in either age group during the study period.

Factors associated with optimal management

Table 3 summarises patient and practice factors associated with receiving a prescription for doxycycline, the preferred treatment for chlamydia. This multivariate analysis indicates that patients over 35 years were 20% less likely to receive doxycycline, and confirms no increase in the use of doxycycline over the study period. Practices in the most and least deprived areas were less likely to prescribe doxycycline. Patterns were similar when analyses were restricted to younger men. In the subsample (54%) for whom an individual deprivation index was available, patients from the least deprived quintile were least likely to receive doxycycline. The odds ratio (adjusted for age group and event year) for the least deprived quintile compared to all others was 0.9 (95% CI = 0.7 to 1.2) for all men (n = 3498) and 1.0 (95% CI = 0.7 to 0.8) for men aged under 35 years (n = 1350).

Table 3.

Factors associated with receiving doxycycline prescription for epididymo-orchitis

| Adjusted odds ratio for receiving doxycycline (95% CIs) for those managed within practice only | ||

|---|---|---|

| All ages (n = 6928) | ≤35 years (n = 2476) | |

| Age group, years | ||

| 15–24 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | |

| 24–35 | 1 | |

| 35–44 | 0.8(0.7 to 1.0) | |

| 45–60 | 0.8(0.7 to 1.0) | |

| Event year | ||

| 2003 | 1 | 1 |

| 2004 | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.4) |

| 2005 | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.4) |

| 2006 | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) |

| 2007 | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) |

| Practice quintile of deprivation | ||

| 1 (least deprived) | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.9) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.7) |

| 3 | 1.4(1.1 to 1.7) | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.7) |

| 4 | 1.3(1.1 to 1.6) | 1.4 (1.0 to 1.8) |

| 5 (most deprived) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 1.0(0.7 to 1.3) |

Excluding 1575 men with diagnostic codes for orchitis did not alter the results. Sensitivity analyses showed that the proportion of cases with evidence of care elsewhere increased as the time window for management was widened for patients managed within practice, but the pattern of care was similar (Appendix 2).

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

A substantial caseload of epididymo-orchitis is seen in primary care and the condition is not restricted to younger men. Incidence fell between 2003 and 2008, with the greatest decline in younger age groups and a relatively stable incidence in older men. Fifty-seven per cent of all cases were managed entirely within primary care and of these, 56% received recommended antibiotics but very few had appropriate testing.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This research examined an unselected population of men with epididymo-orchitis seen in primary care. To the authors' knowledge this is the first study that has considered management by GPs rather than GUM clinics or in secondary care. By using real-time patient records, the study avoided the response bias that affects self-report questionnaire data completed by doctors. As electronic patient record databases are designed primarily for patient care, caution is required. Only coded data were used (based on Read Codes) and information entered as free text in the record was not accessed. This means that there may be some errors both in the classification of men as cases and in the assessment of their management. As epididymo-orchitis is not included in any Quality and Outcomes Framework targets, there is little incentive for GPs to code all elements of the consultation beyond diagnosis and prescribing accurately. Relevant management information, such as advice to attend a GUM clinic, may be present in text only.

Definition as a case requires the GP both to make a diagnosis and record it as a code. The study may have excluded cases diagnosed by the GP but coded using non-specific symptoms rather than a diagnostic code. Equally, some cases with a diagnostic code may not truly reflect a confirmed diagnosis, although sensitivity analyses suggest that the inclusion of cases of possible viral orchitis has not affected results.

The classification of the location of management was complex. The referral (rather than clinical) record was used in the study as evidence of care elsewhere, but this record file may not be used consistently by GPs. Some Read Codes taken as evidence of care elsewhere were non-specific and may not have been actually related to the epididymo-orchitis diagnosis. As expected, as the management window was widened, the proportion with evidence of care elsewhere increased but more unrelated referrals may have been included. The proportion with evidence of care elsewhere increased during the study period, which may be due to better recording of referrals. It was assumed that a prescription was for epididymo-orchitis based on the interval between date of prescription and date of diagnostic code, with similar potential for an overestimate of antibiotic use. However, sensitivity analyses did not indicate that the estimates of treatment were dependent on the length of the management window.

Comparison with existing literature

Incidence estimates for epididymo-orchitis for 1994–2001, based on the Royal College of General Practitioners Weekly Returns Service,1 are higher than those in the present study (38/10 000 person-years in 2001). The difference is probably because this study counted first episode only, whereas the previous estimate counted repeat episodes and relied on the GP classification of new/follow-up consultation.

The decline in incidence may be due to a true fall in incidence of the condition, or may reflect more cases being seen outside general practice, or changes in coding practice. There are consistent data, including from the GPRD, that pelvic inflammatory disease, an associated infection in women, is declining.20–22 It is unclear how this is related to increasing rates of testing for chlamydia in England.23 Literature reviews of the impact of C. trachomatis screening on health outcomes have found little evidence that pelvic inflammatory disease in women is reduced, and the effect on male health outcomes such as epididymo-orchitis has not been studied.24,25 It is possible that the National Chlamydia Screening Programme in England has contributed to the decline in incidence observed, though it is estimated that coverage rates of 30% are required to reduce C. trachomatis prevalence by 29%.26 The greater decline in younger age groups is consistent with a role for the screening programme.

Given the assumed contribution of STIs to epididymo-orchitis, it was surprising to find that incidence was relatively consistent across all age groups of men up to the age of 45 years. This was also reported in a survey of cases in US hospitals, where patients over 35 years accounted for more than 50% of cases, although this study relied only on the number of cases.27 The present data confirm that the disease is not restricted to younger men. It was also surprising to find that there was some evidence that men from more affluent areas were less likely to receive doxycycline. This should be explored in other studies.

Ciprofloxacin was the most commonly prescribed antibiotic, which is consistent with reports from secondary care where quinolones were the treatment of choice for epididymo-orchitis,16,17 whereas doxycycline treatment was the norm in GUM clinics.9 The extremely low rates of C. trachomatis testing reported in the present study are consistent with reports of 3% in a US hospital.17 Cassell et al, using data from a British national probability survey, reported that few men received a C. trachomatis diagnosis in general practice,28 and that rates of non-specific urethritis (often a clinical diagnosis) were disproportionately high in comparison with chlamydia in primary care.19 The rates of investigation for urethritis found in the present study are even lower than the 18% reported by UK urologists.16

Implications clinical practice and future research

The management of epididymo-orchitis in primary care fails to recognise the need to test for a STI, even in younger men. Syndromic treatment is often given with no apparent investigation. This is consistent with what has been seen in urology but is of greater concern due to the large numbers of patients seen in general practice and the potential public health impact. Potential reasons for this syndromic treatment include reluctance of the doctor or patient to undertake invasive and potentially embarrassing tests. There is a need for further research to understand the pattern of care delivered in general practice. Surprisingly high rates of epididymo-orchitis were found in men over 35 years in this study. Work is needed to understand the aetiology, particularly in older men, so that guidelines are evidence based. The accuracy of coded information in primary care databases needs to be confirmed, and the authors plan to consult anonymised free text in a selection of patients to investigate whether textual data alter the estimates of management.

Acknowledgments

This study is based in part on data from the Full Feature General Practice Research Database obtained under license from the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. However, the interpretation and contained in this study are those of the authors alone.

Appendix 1. Code lists: A. Diagnostic codes for epididymo-orchitis

| GPRD Medical | Code Read/OXMISTerm | Read/OXM IS Code |

|---|---|---|

| 205990 | A981311 | Acute gonococcal orchitis |

| 207436 | K242300 | Epididymo-orchitis in diseases EC |

| 216427 | K241200 | Epididymitis unspecified |

| 216428 | K242000 | Epididymo-orchitis with abscess |

| 220371 | 604 AT | ABSCESS TESTIS/TESTICLE |

| 237903 | 0980F | ORCHITIS GONOCOCCAL* |

| 238377 | 6075TT | INFECTION TESTIS |

| 243662 | K241100 | Epididymitis with no abscess |

| 243664 | K241z00 | Epididymitis NOS |

| 252783 | K241.00 | Epididymitis |

| 252784 | K241000 | Epididymitis with abscess |

| 252785 | K241300 | Epididymitis in diseases EC |

| 252786 | K24z.00 | Orchitis and epididymitis NOS |

| 256799 | 604 BA | ORCHITIS ACUTE* |

| 266026 | 604 AE | ABSCESS EPIDIDYMIS |

| 266027 | 604 C | ORCHITIS NOT MUMPS |

| 271289 | K242200 | Epididymo-orchitis unspecified |

| 280340 | K241600 | Chlamydial epididymitis |

| 280341 | K242.00 | Epididymo-orchitis |

| 280342 | K242100 | Epididymo-orchitis with no abscess |

| 289462 | K241400 | Acute epididymitis |

| 298729 | K242z00 | Epididymo-orchitis NOS |

| 304349 | 604 A | EPIDIDYMITIS |

| 304350 | 604 B | ORCHITIS |

| 304351 | 604 D | EPIDIDYMO-ORCHITIS |

| 207435 | K240z00 | Orchitis NOS |

| 234647 | K240200 | Orchitis unspecified |

| 252780 | K24..00 | Orchitis and epididymitis |

| 252781 | K240000 | Orchitis with abscess |

| 252782 | K240300 | Orchitis in diseases EC |

| 280339 | K240100 | Orchitis with no abscess |

| 298728 | K240.00 | Orchitis |

| 265494 | 0980E | GONOCOCCAL EPIDIDYMITIS |

| 265495 | 0980EF | GONOCOCCAL EPIDIDYMO-ORCHITIS |

| 278873 | A981300 | Acute gonococcal epididymo-orchitis |

| 220376 | 6075AD | ABSCESS VAS DEFERENS |

Appendix 1.

Code lists: B. Code lists for chlamydia test.

| GPRD Medical Code | Read/OXMIS Term | Read/OXMIS Code |

|---|---|---|

| 205965 | Chlamydial infection, unspecified | A78AW00 |

| 205969 | Other viral or chlamydial disease NOS | A7z..00 |

| 206063 | [X]Other chlamydial diseases | Ayu6100 |

| 207468 | Female chlamydial pelvic inflammatory disease | K40y100 |

| 214967 | Chlamydial inf of pelviperitoneum oth genitourinary organs | A78A300 |

| 215059 | [X]Chlamydial infection, unspecified | Ayu6200 |

| 225563 | Chlamydia cervicitis | K420900 |

| 242170 | Chlamydial infection of genitourinary tract, unspecified | A78AX00 |

| 242258 | [X]Chlamydial infection of genitourinary tract, unspecified | Ayu4K00 |

| 251351 | Chlamydial infection of lower genitourinary tract | A78A000 |

| 258276 | Chlamydia antigen by ELISA | 43U0.00 |

| 267536 | Chlamydia antigen test | 43U..00 |

| 278838 | Other viral and chlamydial diseases | A7...00 |

| 278847 | Other viral or chlamydial diseases | A78..00 |

| 278852 | Chlamydial infection | A78A.00 |

| 280340 | Chlamydial epididymitis | K241600 |

| 285745 | Chlamydia antigen ELISA positive | 43U1.00 |

| 285746 | Chlamydia antigen ELISA negative | 43U2.00 |

| 287974 | Other specified viral and chlamydial diseases | A78y.00 |

| 289351 | Chlamydial peritonitis | J550400 |

| 297184 | Chlamydial infection of anus and rectum | A78A200 |

| 297190 | Other specified viral or chlamydial diseases | A7y..00 |

| 297288 | [X]Other diseases caused by chlamydiae | Ayu6.00 |

| 302966 | INFECTION CHLAMYDIAL | 0399C |

| 302967 | CHLAMYDIA TRACHOMATIS | 0399CT |

| 307938 | Chlamydia trachomatis IgG level | 43eJ.00 |

| 308079 | Chlamydia trachomatis L2 antibody level | 43eC.00 |

| 308199 | Chlamydia group complement fixation test | 43eF.00 |

| 308461 | Chlamydia antibody level | 43eE.00 |

| 308950 | Chlamydia trachomatis polymerase chain reaction | 43h0.00 |

| 309472 | Chlamydia group antibody level | 43WM.00 |

| 309613 | Chlamydia trachomatis IgM level | 43ez.00 |

| 309766 | Endocervical chlamydia swab | 4JK9.00 |

| 309829 | Urethral chlamydia swab | 4JKA.00 |

| 332003 | Chlamydia trachomatis IgA level | 43n9.00 |

| 342066 | Chlamydia trachomatis antigen test | 43U3.00 |

| 342214 | Chlamydia deoxyribonucleic acid detection | 43jK.00 |

| 342310 | Chlamydia serology | 4JDM.00 |

| 343726 | Urine screen for chlamydia | 68K7.00 |

| 343949 | Chlamydia PCR positive | 43U4.00 |

| 343968 | Chlamydia PCR negative | 43U5.00 |

| 344624 | Urine Chlamydia trachomatis test positive | 46H6.00 |

| 344736 | Urine Chlamydia trachomatis test negative | 46H7.00 |

| 345942 | Chlamydia screening declined | 8I3T.00 |

| 346998 | Chlamydia screening counselling | 677L.00 |

| 347186 | Chlamydia trachomatis contact | 65PJ.00 |

| 347227 | Low vaginal swab for chlamydia taken by patient | 4JKD.00 |

| 347301 | Chlamydial infection of genital organs NEC | A78A500 |

| 347315 | Chlamydia test offered | 9Oq0.00 |

| 347970 | Chlamydia test positive | 43U8.00 |

| 348085 | Chlamydia test negative | 43U6.00 |

| 348329 | Chlamydia test equivocal | 43U7.00 |

Appendix 1.

Code lists: C. Tests for Neisseria gonorrhoea.

| GPRD Medical Code | Read/OXMIS Term | Read/OXMIS Code |

|---|---|---|

| 249090 | Gonorrhoea infect. titre test | 43E6.00 |

| 309228 | Neisseria gonorrhoeae polymerase chain reaction | 43h6.00 |

| 309635 | Neisseria gonorrhoeae nucleic acid detection | 43jA.00 |

| 340376 | Gonococcal swab | 4JLA.00 |

| 342356 | Gonococcal cervical swab | 4JKB.00 |

| 343558 | Gonococcal urethral swab | 4JKC.00 |

| 348093 | Gonorrhoea test positive | 4JQA.00 |

| 348168 | Gonorrhoea test negative | 4JQ8.00 |

| 348381 | Gonorrhoea screening counselling | 677M.00 |

Appendix 1.

Code lists: D. Other microbial tests.

| GPRD Medical Code | Read/OXMIS Term | Read/ OXMIS Code |

|---|---|---|

| 203712 | Infectious titres NOS | 43E..00 |

| 203917 | Sample microscopy | 4I15.00 |

| 203918 | White cells seen on microscopy | 4I15100 |

| 203919 | RBCs seen on microscopy | 4I15200 |

| 203947 | High vaginal swab culture negative | 4JK2100 |

| 203948 | HVS culture – Trichomonas vaginalis | 4JK2200 |

| 205666 | Refer for microbiological test | 8HP2.00 |

| 210464 | PENILE SWAB CULTURE NEGATIVE | L167DN |

| 210515 | HVS TRICHOMONAS VAGINALIS | L1670FT |

| 212942 | Sample culture | 4J17.00 |

| 212962 | Semen sent for C/S | 4JL8.00 |

| 219515 | SWAB CERVICAL ABNORMAL | L167FC |

| 219570 | HVS LACTOBACILLI | L1670FL |

| 221698 | Direct microscopy | 31B1.00 |

| 222017 | Sample: no organism isolated | 4J11.00 |

| 222018 | Sample: organism isolated | 4J12.00 |

| 222020 | Sample: bacteriology – general | 4J2..00 |

| 222022 | Sensitivity-bacteriology | 4J2..13 |

| 222038 | Microbiology NOS | 4JZ..00 |

| 228578 | MICROBIOLOGY REPORT ABNORMAL | L2MA |

| 228611 | HVS CULTURE NEGATIVE | L167FN |

| 228613 | SWAB CULTURE BACTERIAL GROWTH | L167XE |

| 230862 | Blood sent – infectious titres | 43E1.00 |

| 231003 | Parasite in urine | 46H..15 |

| 231090 | Microbiology | 4J...00 |

| 231091 | Sample – microbiological exam | 4J1..00 |

| 231094 | Sample: dir.micr.:no organism | 4J71.00 |

| 231095 | Bacteria on microscopy | 4J72.11 |

| 231108 | Urethral swab culture positive | 4JK1000 |

| 231109 | High vaginal swab: white cells seen | 4JK2500 |

| 231110 | Vaginal swab culture negative | 4JK6.00 |

| 237538 | MICROBIOLOGY REPORT | L2MR |

| 237571 | VAGINAL SWAB CULTURE POSITIVE | L167FZ |

| 237574 | SWAB CULTURE FUNGAL GROWTH | L167XC |

| 237587 | VIRAL TITRES | L189D |

| 237617 | HVS GARDNERELLA VAGINALIS | L1670FG |

| 237618 | HVS YEAST | L1670FY |

| 240066 | Sample: direct micr. organism | 4J7..00 |

| 240075 | High vaginal swab culture positive | 4JK2000 |

| 240076 | HVS culture – Gardnerella vaginalis | 4JK2300 |

| 240077 | Low vaginal swab taken | 4JK3.00 |

| 240078 | Misc. sample for organism | 4JL..00 |

| 246733 | SWAB CERVICAL | L167FA |

| 246735 | URETHRAL SWAB CULTURE NEGATIVE | L167IN |

| 249028 | Swab sent to Lab | 4147.00 |

| 249310 | Culture – general | 4J...11 |

| 249324 | Cervical swab culture positive | 4JK5000 |

| 258486 | Sample: microbiology NOS | 4J1Z.00 |

| 258503 | Urethral swab culture negative | 4JK1100 |

| 258504 | Vaginal swab culture positive | 4JK7.00 |

| 258505 | Penile swab culture positive | 4JK8000 |

| 258506 | Penile swab culture negative | 4JK8100 |

| 265145 | PENILE SWAB | L167D |

| 265146 | PENILE SWAB CULTURE POSITIVE | L167DP |

| 265197 | HVS WBC | L1670FW |

| 267662 | Urine microscopy: orgs/FBs | 46H..00 |

| 267735 | Sensitivity-microbiol. | 4J...12 |

| 267736 | Sample: organism sensitivity | 4J15.00 |

| 267739 | O/E: stained micr.: organism | 4J8..00 |

| 267754 | Vaginal swab taken | 4JK..11 |

| 267755 | Vulval swab taken | 4JK4.00 |

| 267756 | Penile swab taken | 4JK8.00 |

| 267757 | GUT swab NOS | 4JKZ.00 |

| 274368 | HVS EPITHELIAL CELLS | L1670FE |

| 276782 | Culture – bacteriology | 4J2..12 |

| 276783 | Sample sent for culture/sensit | 4J22.00 |

| 276800 | GUT sample taken for organism | 4JK..00 |

| 276801 | High vaginal swab taken | 4JK2.00 |

| 276802 | Cervical swab taken | 4JK5.00 |

| 283373 | HVS | L167F |

| 283374 | HVS CULTURE POSITIVE | L167FP |

| 283375 | VAGINAL SWAB CULTURE NEGATIVE | L167FY |

| 285938 | Microscopy, culture and sensitivities | 4I16.00 |

| 285943 | Sample: bacteria cultured | 4J23.00 |

| 285955 | Urethral swab taken | 4JK1.00 |

| 285958 | Microbiology test | 4JQ..00 |

| 292462 | MICROBIOLOGY REPORT NORMAL | L2MN |

| 292509 | SWAB CERVICAL NORMAL | L167FB |

| 292511 | URETHRAL SWAB CULTURE POSITIVE | L167IP |

| 292515 | SWAB CULTURE NO GROWTH | L167XB |

| 295145 | High vaginal swab: fungal organism isolated | 4JK2400 |

| 295146 | Cervical swab culture negative | 4JK5100 |

| 297019 | Microbiology report received | 9ND3.00 |

| 301878 | VAGINAL SWAB | L167FX |

| 301879 | URETHRAL SWAB | L167I |

| 301882 | SWAB CULTURE YEAST GROWTH | L167XD |

| 308931 | Bacterial antibody level | 43e..00 |

| 309727 | Microscopy | 4JS..00 |

| 331709 | Gram stain microscopy | 4JS0.00 |

| 332043 | Anaerobic culture | 4J18.00 |

| 339918 | Concentrate microscopy | 4JS2.00 |

| 340342 | Genital microscopy, culture and sensitivities | 4I1C.00 |

| 340745 | Fluid microscopy, culture and sensitivities | 4I1D.00 |

| 343815 | Semen microscopy | 49L..00 |

| 343816 | Aerobic culture | 4J19.00 |

| 344353 | Additional urine tests | 46h..00 |

| 345784 | Culture for fungi | 4J45.00 |

| 350883 | Low vaginal swab taken by patient | 4JKE.00 |

| 350959 | Self taken low vaginal swab | 4JKE.11 |

| 203821 | Urine exam. – general | 461..00 |

| 203822 | Urine dipstick test | 4618.00 |

| 203825 | Urine protein test = + | 4674.00 |

| 203826 | Urine protein test = ++ | 4675.00 |

| 203827 | Urine ketone test = ++++ | 4687 |

| 203831 | Urine sent for microscopy | 46D1.00 |

| 203832 | Urine microscopy: no casts | 46E1.00 |

| 203840 | Urine culture – no growth | 46U1.00 |

| 203841 | Urine culture – E. coli | 46U3.00 |

| 203842 | Urine culture – Str. faecalis | 46U5.00 |

| 203843 | Urine culture – Staph. albus | 46U6.00 |

| 203844 | Urine culture – Bacteria OS | 46U8.00 |

| 210442 | URINE INVESTIGATIONS | L131AA |

| 210443 | URINE CASTS PRESENT | L 132CP |

| 210520 | ABNORMAL URINE TEST NOT YET DIAGNOSED | L2590AN |

| 210544 | URINE NEGATIVE | L7891N |

| 211701 | STERILE PYURIA | 7891D |

| 212820 | Urine examination | 46...00 |

| 212821 | MSU sent to lab. | 4615.00 |

| 212822 | Urine inspection | 462..00 |

| 212823 | Urine: cloudy | 4627 |

| 212827 | Urine protein test = ++++ | 4677 |

| 212830 | Urine: trace non-haemol. blood | 4693.00 |

| 212840 | Urine Microscopy: white cells | 46G8.00 |

| 212959 | Urine for culture | 4JJ..13 |

| 212960 | Early morning urine | 4JJ..14 |

| 212961 | Urine sample for organism NOS | 4JJZ.00 |

| 219490 | MSU NORMAL | L133MN |

| 219573 | URINE ALBUMIN+++ | L2400CC |

| 219576 | CASTS IN URINE POSITIVE | L2591PV |

| 221916 | MSU = no abnormality | 4616.00 |

| 221921 | Urine blood test | 469..00 |

| 221922 | Urine bacteria test NOS | 46BZ.00 |

| 221923 | Urine microscopy: no crystals | 46F1.00 |

| 221924 | Sterile pyuria | 46G4.12 |

| 221925 | Urine micr.: bacteria present | 46H4.00 |

| 221955 | Urine culture – Escherich. coli | 46U3.11 |

| 222034 | MSU sent for bacteriology | 4JJ2.00 |

| 228591 | URINE CULTURE POSITIVE GROWTH | L133P |

| 228673 | URINE ALBUMIN+ | L2400AA |

| 230985 | Urinalysis requested | 4612.00 |

| 230986 | Urine = normal on inspection | 4621.00 |

| 230987 | Urine inspection NOS | 462Z.00 |

| 230993 | Urine protein test | 467..00 |

| 230994 | Urine protein test negative | 4672.00 |

| 230995 | Urine dipstick for protein | 4679.00 |

| 230996 | Urine: trace haemolysed blood | 4694.00 |

| 230997 | Urine microscopy: no cells | 46G1.00 |

| 230998 | RBCs – red blood cells in urine | 46G2.11 |

| 230999 | Urine micr.: leucocytes present | 46G4.00 |

| 231000 | Leucocytes in urine | 46G4.11 |

| 231001 | Urine micr.: leucs – % polys | 46G5.00 |

| 231002 | Pus cells in urine | 46G7.11 |

| 231003 | Parasite in urine | 46H..15 |

| 231031 | Urine culture – mixed growth | 46U2.00 |

| 237549 | URINE CULTURE | L133 |

| 237622 | URINE ALBUMIN++ | L2400BB |

| 237649 | URINE TEST | L7890T |

| 239977 | Urine protein test = trace | 4673.00 |

| 239980 | Urine microscopy – general NOS | 46DZ.00 |

| 239981 | Urine microscopy – casts | 46E..00 |

| 239982 | Urine microscopy: epith. casts | 46E2.00 |

| 239986 | FB in urine – microscopy | 46H..12 |

| 239987 | Urine microscopy: no orgs/FBs | 46H1.00 |

| 240073 | Mid-stream urine sample | 4JJ..12 |

| 240074 | Urine sent for culture | 4JJ3.00 |

| 246820 | MSU | L7891MS |

| 249215 | Urine exam. – general NOS | 461Z.00 |

| 249223 | Urine dipstick for blood | 4698.00 |

| 249224 | Urine bacteriuria test | 46B..00 |

| 249225 | Urine bacteria test: positive | 46B3.00 |

| 249226 | Urine microscopy – general | 46D..00 |

| 249227 | Urine micr.: leucs – % lymphs | 46G6.00 |

| 249228 | Urine microscopy: red cells | 46G9.00 |

| 249229 | Bacteria in urine O/E | 46H..11 |

| 249242 | Urine test NOS | 46Z..00 |

| 249322 | Urine sample for organism | 4JJ..00 |

| 255953 | URINE WBC'S ABSENT | L132WA |

| 255954 | URINE WBC'S PRESENT | L132WP |

| 258374 | MSU = equivocal | 461A.00 |

| 258375 | Urine: red – blood | 4625.00 |

| 258376 | Urine: looks clear | 4626 |

| 258381 | Proteinuria | 4678.00 |

| 258384 | Urine blood test = ++ | 4696.00 |

| 258385 | Urine blood test = +++ | 4697.00 |

| 258386 | Urine bacteria test: negative | 46B2.00 |

| 258387 | Urine microscopy: casts NOS | 46EZ.00 |

| 258390 | Urine microscopy: cells | 46G..00 |

| 258391 | Urine microscopy: RBCs present | 46G2.00 |

| 258392 | Urine microscopy: pus cells | 46G7.00 |

| 258398 | Urine protein | 46N..00 |

| 258399 | Urine protein abnormal | 46N2.00 |

| 258414 | Urine culture | 46U..00 |

| 258502 | MSU sent for C/S | 4JJ1.00 |

| 265127 | URINE CULTURE NO GROWTH | L133N |

| 265202 | PROTEINURIA | L2020PV |

| 267459 | Urine sample sent to Lab | 4146.00 |

| 267646 | Urine tests | 46...11 |

| 267647 | MSU – general | 461..11 |

| 267648 | MSU = no growth | 4619.00 |

| 267653 | Blood in urine test | 469..11 |

| 267655 | Urine blood test = + | 4695.00 |

| 267656 | Urine blood test NOS | 469Z.00 |

| 267658 | Urine microscopy = abnormality | 46D3.00 |

| 267659 | Urine microscopy: crystals | 46F..00 |

| 267660 | Urine micr.: uric acid crystals | 46F3.00 |

| 267661 | Urine microscopy: no white cells | 46G1100 |

| 267662 | Urine microscopy: orgs/FBs | 46H..00 |

| 274306 | URINE EPITHELIAL CELLS PRESENT | L132EP |

| 274307 | MSU ABNORMAL | L 133MA |

| 276691 | Urinalysis – general | 461..12 |

| 276695 | Urine blood test = negative | 4692.00 |

| 276697 | Urine microscopy:hyaline casts | 46E3.00 |

| 276799 | Catheter urine -> culture. | 4JJ4.00 |

| 285852 | Urinalysis = no abnormality | 4613.00 |

| 285853 | Urinalysis = abnormal | 4614.00 |

| 285854 | MSU = abnormal | 4617.00 |

| 285855 | Urine: pale | 4624 |

| 285858 | Urine protein test = +++ | 4676.00 |

| 285859 | Urine protein test NOS | 467Z.00 |

| 285866 | Urine micr.: orgs/FBs NOS | 46HZ.00 |

| 292486 | URINE INVESTIGATIONS ABNORMAL | L 131 AC |

| 295030 | Urine microscopy: no epithelial cells | 46G1000 |

| 295031 | Urine micr.: epithelial cells | 46G3.00 |

| 301855 | URINE INVESTIGATIONS NORMAL | L131AB |

| 302605 | Urine microalbumin positive | 46w0.00 |

| 333181 | Urine leucocyte test | 46f..00 |

| 333245 | Urine leucocyte test = + | 46f2.00 |

| 333246 | Urine leucocyte test = ++ | 46f3.00 |

| 333247 | Urine leucocyte test = +++ | 46f4.00 |

| 335402 | Urine microscopy | 46Z1.00 |

| 339791 | Urine leucocyte test = negative | 46f1.00 |

| 340095 | Urine microscopy: yeasts | 46H5.00 |

Appendix 2. Results of sensitivity analyses

| 28-day management window (1575 orchitis-only cases excluded) | <35 years, % | ≥35 years, % |

|---|---|---|

| Management | ||

| Managed in practice | 56.0 | 58.2 |

| No evidence of management | 19.0 | 16.9 |

| Evidence of care elsewhere | 25.0 | 24.9 |

| Drug prescribed | ||

| Any recommended drug | 56.6 | 55.7 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 34.9 | 36.7 |

| Doxycycline | 20.7 | 18.1 |

| Test carried out | ||

| Chlamydia trachomatis test | 4.6 | 1.3 |

| Microbial test | 11.8 | 11.1 |

| Urine test | 20.1 | 22.1 |

| 42-day management window | ||

| Management | ||

| Managed in practice | 52.5 | 55.3 |

| No evidence of management | 17.8 | 15.2 |

| Evidence of care elsewhere | 29.7 | 29.6 |

| Drug prescribed | ||

| Any recommended drug | 55.4 | 55.4 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 34.4 | 37.0 |

| Doxycycline | 20.5 | 17.5 |

| Test carried out | ||

| Chlamydia trachomatis test | 4.5 | 1.5 |

| Microbial test | 13.0 | 13.0 |

| Urine test | 20.8 | 23.8 |

| 60-day management window | ||

| Management | ||

| Managed in practice | 50.3 | 52.4 |

| No evidence of management | 16.7 | 13.9 |

| Evidence of care elsewhere | 33.1 | 33.7 |

| Drug prescribed | ||

| Any recommended drug | 54.6 | 55.1 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 34.1 | 37.0 |

| Doxycycline | 20.0 | 17.5 |

| Test carried out | ||

| Chlamydia trachomatis test | 4.5 | 1.6 |

| Microbial test | 13.5 | 13.7 |

| Urine test | 22.6 | 25.0 |

| 90-day management window | ||

| Management | ||

| Managed in practice | 46.8 | 48.7 |

| No evidence of management | 15.0 | 12.3 |

| Evidence of care elsewhere | 38.2 | 38.9 |

| Drug prescribed | ||

| Any recommended drug | 54.3 | 43.6 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 34.0 | 36.9 |

| Doxycycline | 20.4 | 17.2 |

| Test carried out | ||

| Chlamydia trachomatis test | 4.6 | 1.6 |

| Microbial test | 14.2 | 14.7 |

| Urine test | 23.1 | 27.1 |

Funding body

Access to the GPRD database was funded through the Medical Research Council's license agreement with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the GPRD Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (protocol number 08_097).

Competing interests

The authors have stated that there are none.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Simms I, Fleming DM, Lowndes CM, et al. Surveillance of sexually transmitted diseases in general practice: a description of trends in the Royal College of General Practitioners Weekly Returns Service between 1994 and 2001. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17(10):693–698. doi: 10.1258/095646206780070992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins MM, Stafford RS, O'Leary MP, Barry MJ. How common is prostatitis? A national survey of physician visits. J Urol. 1998;159(4):1224–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoosen AA, O'Farrell N, van den EJ. Microbiology of acute epididymitis in a developing community. Genitourin Med. 1993;69(5):361–363. doi: 10.1136/sti.69.5.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De JZ, Pontonnier F, Plante P, et al. The frequency of Chlamydia trachomatis in acute epididymitis. Br J Urol. 1988;62(1):76–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1988.tb04271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant JB, Costello CB, Sequeira PJ, Blacklock NJ. The role of Chlamydia trachomatis in epididymitis. Br J Urol. 1987;60(4):355–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1987.tb04985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulcahy FM, Bignell CJ, Rajakumar R, et al. Prevalence of chlamydial infection in acute epididymo-orchitis. Genitourin Med. 1987;63(1):16–18. doi: 10.1136/sti.63.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawkins DA, Taylor-Robinson D, Thomas BJ, Harris JR. Microbiological survey of acute epididymitis. Genitourin Med. 1986;62(5):342–344. doi: 10.1136/sti.62.5.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. 2001 Guideline for the management of epididymo-orchitis. http://www.bashh.org/documents/31/31.pdf (accessed 9 Mar 2010) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Dale AWS, Wilson JD, Forster GE, et al. Management of epididymo-orchitis in genitourinary medicine clinics in the United Kingdom's North Thames region 2000. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12(5):342–345. doi: 10.1258/0956462011923066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines 2006. Epididymitis. http://www.cdc.gov/std/Treatment/2006/epididymitis.htm (accessed 9 Mar 2010)

- 11.Trei JS, Canas LC, Gould PL. Reproductive tract complications associated with Chlamydia trachomatis infection in US Air Force males within 4 years of testing. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(9):827–833. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181761980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMillan A, Pakianathan M, Mao JH, Macintyre CC. Urethral stricture and urethritis in men in Scotland. Genitourin Med. 1994;70(6):403–405. doi: 10.1136/sti.70.6.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weidner W, Schiefer HG, Krauss H. Role of Chlamydia trachomatis and mycoplasmas in chronic prostatitis. A review. Urol Int. 1988;43(3):167–173. doi: 10.1159/000281331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ness RB, Markovic N, Carlson CL, Coughlin MT. Do men become infertile after having sexually transmitted urethritis? An epidemiologic examination. Fertil Steril. 1997;68(2):205–213. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81502-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Better prevention, better services, better sexual health – the national strategy for sexual health and HIV. London: Department of Health; 2001. Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drury NE, Dyer JP, Breitenfeldt N, et al. Management of acute epididymitis: are European guidelines being followed? Eur Urol. 2004;46(4):522–524. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tracy CR, Costabile RA. The evaluation and treatment of acute epididymitis in a large university based population: are CDC guidelines being followed? World J Urol. 2009;27(2):259–263. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.General Practice Research Database. http://www.gprd.com/home/ (accessed 9 Mar 2010)

- 19.Cassell JA, Mercer CH, Sutcliffe L, et al. Trends in sexually transmitted infections in general practice 1990–2000: population based study using data from the UK general practice research database. BMJ. 2006;332(7537):332–334. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38726.404120.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owusu-Edusei K, Bohm MK, Chesson HW, Kent CK. Chlamydia and gonorrhoea screening and pelvic inflammatory disease diagnoses: can simple time series analyses provide some insights?. Oral presentation at 18th Conference of International Society for STD Research; London. 2009. OS.2.6.06. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rekart M, Gilbert M, Kim P, et al. Documenting the success of Chlamydia control in British Columbia. 2009. London; Poster presentation at 18th Conference of International Society for STD Research. 2009. P.4.64. [Google Scholar]

- 22.French C, Hughes G, Yung M, et al. Estimation of the rate of pelvic inflammatory disease diagnoses: trends in England, 2000–2008. Sex Transm Dis. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f22f3e. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.NHS National Chlamydia Screening Program. New Frontiers: Annual report of the National National Chlamydia Screening Programme in England 2005/6. http://www.chlamydiascreening.nhs.uk/ps/assets/pdfs/publications/reports/NCSPa-rprt-05_06.pdf (accessed 9 Mar 2010)

- 24.Low N, Bender N, Nartey L, et al. Effectiveness of chlamydia screening: systematic review. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(2):435–48. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gift TL, Gaydos CA, Kent CK, et al. The program cost and cost- effectiveness of screening men for Chlamydia to prevent pelvic inflammatory disease in women. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(11 suppl):S66–S75. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818b64ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turner KM, Adams EJ, Lamontagne DS, et al. Modelling the effectiveness of chlamydia screening in England. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(6):496–502. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.019067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tracy CR, Steers WD, Costabile R. Diagnosis and management of epididymitis. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35(1):101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cassell JA, Mercer CH, Fenton KA, et al. A comparison of the population diagnosed with chlamydia in primary care with that diagnosed in sexual health clinics: implications for a national screening programme. Public Health. 2006;120(10):984–988. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]