Abstract

Background and Aims

Adventitious embryony from nucellar cells is the mechanism leading to apomixis in Citrus sp. However, singular cases of polyembryony have been reported in non-apomictic genotypes as a consequence of 2x × 4x hybridizations and in vitro culture of isolated nucelli. The origin of the plants arising from the aforementioned processes remains unclear.

Methods

The genetic structure (ploidy and allelic constitution with microsatellite markers) of plants obtained from polyembryonic seeds arising from 2x × 4x sexual hybridizations and those regenerated from nucellus culture in vitro was systematically analysed in different non-apomictic citrus genotypes. Histological studies were also conducted to try to identify the initiation process underlying polyembryony.

Key Results

All plants obtained from the same undeveloped seed in 2x × 4x hybridizations resulted from cleavage of the original zygotic embryo. Also, the plants obtained from in vitro nucellus culture were recovered by somatic embryogenesis from cells that shared the same genotype as the zygotic embryos of the same seed.

Conclusions

It appears that in non-apomictic citrus genotypes, proembryos or embryogenic cells are formed by cleavage of the zygotic embryos and that the development of these adventitious embryos, normally hampered, can take place in vivo or in vitro as a result of two different mechanisms that prevent the dominance of the initial zygotic embryo.

Keywords: Citrus, polyembryony, apomixis, embryo cleavage, nucellus, interploid hybridization

INTRODUCTION

The polyembryony phenomenon was discovered by Leeuwenhoek in 1719, who observed the formation of two plantlets from the same citrus seed (Batygina and Vinogradova, 2007). Later, Strasburger (1878) reported the formation of adventive embryos from citrus nucellar cells and called this phenomenon nucellar or adventive polyembryony. The main classification criteria for polyembryony include the origin of the initial embryogenic cells, the mode of embryo formation and genetic traits. Based on the cellular origin of embryogenesis, polyembryony can be divided into two main types: gametophytic and sporophytic. Gametophytic polyembryony includes apogamety and apospory, whereas sporophytic polyembryony encompasses nucellar, integumental, monozygotic cleavage and endospermal polyembryony (Batygina and Vinogradova, 2007). With the exception of the latter two, these different forms of polyembryony are associated with apomixis, defined as asexual reproduction through seeds (Savidan, 2000). In citrus, apomictic and non-apomictic genotypes are found in the diploid germplasm (Frost and Soost, 1968). There are three basic taxa from which all cultivated citrus have originated, namely pummelos [Citrus maxima (L.) Osb.], citrons (C. medica L.) and mandarins (C. reticulata Blanco) (Nicolosi et al., 2000). The most widely grown species, like sweet oranges [C. sinensis (L.) Osb.], lemons [C. limon (L.) Burm f.], grapefruits (C. paradisi Macf.), limes [C. aurantifolia (Christm.) Swing.], clementines (C. clementina Hort. ex Tan.) and satsumas [C. unshiu (Mak.) Marc.], originated from crosses of the tree basic taxa (Nicolosi et al., 2000). Most citrus genotypes are apomictic, with the exception of all citron, pummelo and clementine cultivars and some mandarin hybrids. Sporophytic adventitious embryony is the mechanism leading to facultative apomixis in citrus. During apomictic citrus seed formation, embryos are initiated directly from the maternal nucellar cells surrounding the embryo sac containing a developing zygotic embryo (Kobayashi et al., 1981). In vivo, full development of the nucellar embryos is endosperm-dependent, and thus prior fertilization is required (Esen and Soost, 1977). During embryo sac expansion, nucellar embryos develop alongside the zygotic embryo, which may or may not develop fully. The majority of seedlings arising from polyembryonic seeds correspond to the maternal genotype, and are called nucellar seedlings. However, the frequency with which nucellar seedlings arise can vary depending on the genotype and environmental conditions (Khan and Roose, 1988). Zygotic seedlings can be discriminated from their nucellar counterparts based on isoenzymes (Iglesias et al., 1974), random amplification of polymorphic DNA (Luro et al., 1995) and simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers (Ruiz et al., 2000). Also, a major gene linked to apomixis has recently been identified by Kepiro and Roose (2010), by using amplified fragment length polymorphism markers.

Non-apomictic citrus genotypes usually have only one sexual embryo per seed, although occasionally extra embryos can arise either from the fission of one fertilized egg or from two or more functional embryo sacs in a single ovule (Frost, 1926; Bacchi, 1943; Cameron and Garber, 1968; Frost and Soost, 1968). Frost (1938) described monozygotic polyembryony by cleavage of the sexual embryo in hybrids with identical phenotype. Subsequently, Bacchi (1943) histologically described two gametophytes in the same ovule of ‘Foster’ grapefruit. More recently, on analysing 633 hybrids of citrus rootstocks, Medina-Filho et al. (1993) identified ten monozygotic twin hybrids and two dizygotic pairs by isozyme analysis. Traditionally, apomictic genotypes are referred to as polyembryonic and non-apomictic genotypes as monoembryonic, although these terms may cause confusion when attempting to distinguish nucellar embryony from sexual twinning (Kepiro and Roose, 2007).

Consistent formation of multiple embryos in seeds of non-apomictic citrus genotypes has been observed in two systems. In the first case, Oiyama and Kobayashi (1990) reported multiple embryos in seeds of non-apomictic clementines and ‘Iyokan’ mandarin (C. iyo Hort. ex Tan.) pollinated with tetraploid ‘Kawano Natsudaidai’ (C. natsudaidai Hayata). In such crosses, different types of seeds are obtained and multiple small embryos are observed exclusively in partially developed seeds containing triploid embryos. Similarly, we have made the same observations in many 2x × 4x crosses in our triploid breeding programme; however, the causes underlying this type of polyembryony remain unknown. Oiyama and Kobayashi (1990) analysed one isoenzymatic system and concluded that all zygotic embryos from the same seed arose from cleavage of the original zygotic embryo. However, due to the very limited scale of analysis, this conclusion requires confirmation, as the possibility that polyembryony originates from two or more functional embryo sacs in a single ovule (Bacchi, 1943) cannot be discarded.

The second case concerns embryo production by nucelli isolated from developing seeds and cultured in vitro after the zygotic embryo has been discarded. This technique was developed with a view to recovering pathogen-free nucellar plants of non-apomictic genotypes (Rangan et al., 1968; Esan, 1973). Indeed, in vivo nucellar embryony of apomictic genotypes was widely used in the past to obtain virus-free plants, as most pathogens are not transmitted through embryogenesis (Weathers and Calavan, 1959; Roistacher, 1979). Navarro et al. (1985) also used this procedure to recover pathogen-free plants of several clementine varieties. However, long-term field evaluation of regenerated plants showed that their phenotype differed from the original seed source plants. In the aforementioned study (Navarro et al., 1985), phenotypic differences with the original plants were found in the greenhouse and when several plants were recovered from the same nucellus all were alike. Isoenzymatic analysis of plants produced by each nucellus indicated that plants regenerated from the same nucellus were identical, but one nucellus differed from another and from the maternal plant (Navarro et al., 1985). Although the embryos produced by nucellus cultured in vitro are thought to originate from the nucellus, their true origin remains unclear.

The present study aims to answer the following questions. (1) Does pollination with a tetraploid parent systematically induce the formation of polyembryonic seeds in the non-apomictic citrus genotypes? (2) What is the origin of in vivo polyembryony in 2x × 4x crosses and in vitro embryogenesis from isolated nucellus of non-apomictic citrus genotypes? (3) Might these two phenomena have the same biological origin?

To do so, we systematically analysed the genetic structure (ploidy and microsatellite allelic constitution) of plants obtained from polyembryonic seeds arising from 2x × 4x sexual hybridizations or regenerated from nucellus culture in vitro of different non-apomictic citrus genotypes. Histological studies were also conducted to try to identify the initiation process of polyembryony.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Hybridizations 2x × 4x

Plant material

The non-apomictic clementine genotypes ‘Bruno’, ‘Fina’, ‘Hernandina’, ‘Clemenules’ and ‘Tomatera’ were used as female parents. Diploid ‘Nova’ mandarin [C. clementina × (C. paradisi × C. tangerina)] and tetraploid ‘Nova’ mandarin, ‘Orlando’ tangelo (C. paradisi × C. tangerina) and ‘Pineapple’ sweet orange were used as male parents. The tetraploid parents were previously selected from seedlings of diploid cultivars, which are doubled diploid arising from chromosome doubling of the maternal genotype, frequent in citrus (Ollitrault et al., 2008). All genotypes belong to the Citrus Germplasm Bank of the Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Agrarias (IVIA).

Pollination and embryo rescue

Between 50 and 150 flowers of clementines were hand-pollinated with each male parent. Fruits were collected at maturity and seeds were extracted and surface sterilized with a sodium hipochloride solution (0·5 % active chlorine) for 10 min and washed with sterile water.

Embryos were isolated from undeveloped seeds under aseptic conditions with the aid of a stereoscopic microscope and cultivated on Petri dishes containing the Murashige and Skoog (1962) culture medium with 50 g L−1 sucrose, 500 g L−1 malt extract supplemented with vitamins (100 mg L−1 myo-inositol, 1 mg L−1 pyridoxine hydrochloride, 1 mg L−1 nicotinic acid, 0·2 mg L−1 thiamine hydrochloride, 4 mg L−1 glycine) and 8 g L−1 Bacto agar (MS culture medium). After germination plants were transferred to 25 × 150-mm test tubes with MS culture medium without malt extract. Cultures were maintained at 24 ± 1 °C, 60 % humidity and 16 h daily exposure to 40 µE m−2 s−1 illumination.

Hybridizations 2x × 2x

Plant material

‘Clemenules’ clementine and ‘Fortune’ mandarin (C. clementina × C. tangerina) non-apomictic female parents and Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. ‘Benecke’ male parent from the IVIA Citrus Germplasm Bank were used. Intergeneric hybridizations of citrus with P. trifoliata do not induce problems related to compatibility, seed-set, fruit-set or plant production. Additionally, trifoliate leaves of P. trifoliata are a dominant trait and constitute a strong morphological marker determining the hybrid origin of progenies.

Pollination and nucellus culture in vitro

One hundred flowers of ‘Clemenules’ clementine and 100 flowers of ‘Fortune’ mandarin were hand pollinated with pollen of P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’. Fruits were collected 13–15 weeks after pollination and the nucellus of the immature seeds were excised aseptically by removing both integuments and the zygotic embryo at heart-shaped to early cotyledonary stage of development (Fig. 1). Only nucelli from seeds with clearly visible zygotic embryos were cultured. Nucelli were cultivated in MS culture medium and one nucellus was planted in each 25 × 150-mm culture tube with the chalazal end embedded in the medium. Cultures were kept at 24 ± 1 °C, 60 % humidity and 16 h daily exposure to 40 µE m−2 s−1 illumination. Zygotic embryos extracted from nucelli were also cultivated separately in 25 × 150-mm culture tubes containing the MS culture medium and kept under the same conditions.

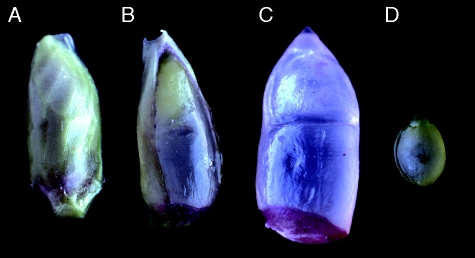

Fig. 1.

(A) Developmental stage of a seed used from nucellus culture in vitro extracted 13–15 weeks after pollination. (B) Seed with both integuments partially eliminated with the zygotic embryo inside. (C,D) Nucellus without integuments and zygotic embryo extracted at early cotyledonary stage.

Transfer to soil

Recovered plants were transferred to pots containing steam-sterilized artificial soil mix suitable for citrus growing (40 % black peat, 29 % coconut fibre, 24 % washed sand and 7 % perlite). Pots were enclosed in polyethylene bags, closed with rubber bands and placed in a shaded area of a temperature-controlled greenhouse set at 18–25 °C. After 8–10 d, the bags were opened, then 8–10 d later the bags were removed and the plants grown under regular greenhouse conditions (Navarro and Juárez, 2007).

Ploidy-level analysis

Ploidy level was determined by flow cytometry according to the methodology described by Aleza et al. (2009). Each sample comprised a small leaf-piece of the analysed plant (approx. 0·5 mm2) with a similar leaf-piece from a diploid control plant. Samples were chopped using a razor blade in a nuclei isolation solution (High Resolution DNA Kit Type P, solution A; Partec, Münster, Germany). Nuclei were filtered through a 30-μm nylon filter and stained with a DAPI (4′,6-diamine-2-phenylindol) (High Resolution DNA Kit Type P, solution B; Partec) solution. After 5 min incubation, stained samples were run in a Ploidy Analyzer (PA) (Partec) flow cytometer equipped with an HBO 100-W high-pressure mercury bulb and both KG1 and BG38 filter sets. Histograms were analysed using the Dpac v2·0 software (Partec), which determines peak position, coefficient of variation (CV) and the relative ploidy index of the samples.

Genetic analysis

Genetic analysis was carried out using 13 SSR markers (Kijas et al., 1997; Froelicher et al., 2008; Luro et al., 2008). Genomic DNA was extracted according to Dellaporta and Hicks (1983), with slight modifications. PCR amplifications of the samples were performed using a Termocycler ep gradient S (Eppendorf) in a final volume of 17 mL containing 0·8 U Taq DNA polymerase (Need), 30 ng of citrus DNA, 1·25 mm of each dNTP, 5 mm MgCl2, 750 mm Tris-HCl (pH 9), 200 mm (NH4)2SO4, 0·001 % (v/v) bovine serum albumin, and 5 µm reverse and forward primers. The following PCR programme was applied: denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min; followed by 35 repeats 30 s at 94 °C, 1 min at 50 or 55 °C, and 45 s at 72 °C; and a final elongation step of 4 min at 72 °C. PCR products were separated by means of vertical denaturalized electrophoresis (acrylamide-bis acrylamide 6 %, urea 7 m) buffer TBE 0·5× (Tris, acid boric and EDTA 0·5 m, pH 8) in a BioRad DCode, according to the methodology described by Froelicher et al. (2007). The amplified fragments were detected by silver staining (Benbouzas et al., 2006).

Parental allelic structure was analysed to select a set of primers for each parental combination to discriminate between nucellar and zygotic origin, as well as between independent zygotic origins. Results were processed using cluster analyses based on the Dice dissimilarity coefficient by the Weighted Neighbour Joining method. All these calculations were performed with Darwin V.5·0·155 software (Perrier et al., 2003; Perrier and Jacquemoud-Collet, 2006).

Histological characterization

Ovules and seeds from fruits obtained from ‘Clemenules’ clementine pollinated with P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’ were collected weekly after pollination and fixed in FAA (formaldehyde, glacial acetic acid and alcohol 50 %). Samples were embedded in paraffin, cut into 10-μm sections and stained with PAS (Periodic acid-Schiff reaction) according to the general methodology described by Hotchkiss (1948). Observations were recorded with an E800 Eclipse Nikon microscope.

RESULTS

Identification of molecular markers for unambiguous genetic characterization

SSR markers were selected to discriminate between parentals and to estimate the probability of identity between two independent zygotic plants and between zygotic and nucellar plants obtained in 2x × 4x and 2x × 2x hybridizations. From the 13 SSR markers analysed, eight indicated important polymorphism among the parents of the 2x × 4x progenies. With all the SSR markers used, identical profiles were obtained for the different clementine genotypes and consequently, hereafter they are all referred to under the generic name of clementines.

The markers used are known to be monolocus; therefore, the genotypes of the diploid plants could be inferred directly from their profiles. Clementines were heterozygous for all the markers and shared two, one or no alleles with the male parent according to the markers and the parental combination. The SSR analysis was carried out using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and silver staining. We preferred not to estimate allelic doses in the triploid genotypes. Thus, to calculate the probability of identity between two progenies for one locus, we considered that the genotypes ab, aab and abb (where a and b are two alleles at the considered locus) were indistinguishable. The theoretical probability of identity between two independent zygotic plants and between zygotic and nucellar plants for one locus has been estimated for the different allelic combinations without distinction of allelic dose (Table 1, and Supplementary Data, available online). Given that the analysed markers are genetically independent, the probability of observing a zygotic seedling identical to the nucellar ones was calculated by multiplying the corresponding probability for each marker (Table 2). These theoretical probabilities fluctuated between 0, in the hybridisation of clementine × tetraploid ‘Orlando’ tangelo, and 4 × 10−6 in the clementine × tetraploid ‘Nova’ mandarin (Table 2). The probabilities of identity for two independent zygotic plants were calculated in the same way and oscillated between 2 × 10−3 in clementine × tetraploid ‘Orlando’ tangelo and 1 × 10−3 in the other two hybridizations.

Table 1.

Theoretical probability of identity between two zygotic genotypes and between zygotic and nucellar plants obtained in 2x × 4x hybridizations in terms of parental SSR profiles

| Female parent | Male parent | PIZ* | PINZ† |

|---|---|---|---|

| ab | aaaa / bbbb | 1/2 | 1/2 |

| aabb | 51/72 | 5/6 | |

| aacc / bbcc | 1/4 | 1/12 | |

| ccdd | 1/4 | 0 | |

| cccc / dddd | 1/2 | 0 |

* PIZ, probability of identity between two independent zygotic genotypes (without allelic dosis estimation).

† PINZ, probability of identity between nucellar and zygotic plants (without allelic dosis estimation).

Table 2.

SSR marker selection and probability of identity between two independent zygotic plants and between zygotic and nucellar genotypes obtained in 2x × 4x hybridizations

| Parents |

SSR loci used for each 2x ×4x hybridization |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSR locus | Clementine | Nova 4x | Orlando 4x | Pineapple 4x | Clementine × Nova 4x | Clementine × Orlando 4x | Clementine × Pineapple 4x |

| Ci01C06 | ab | aacc | bbcc | bbdd | Not used | Used | Used |

| Ci01C07 | ab | aacc | aacc | aadd | Used | Used | Not used |

| Ci02B07 | ab | bbcc | ccdd | aadd | Used | Used | Used |

| Ci05A05 | ab | aacc | aacc | aacc | Used | Used | Used |

| Ci07C07 | ab | aaaa | cccc | bbbb | Not used | Used | Used |

| CAC 15 | ab | aabb | aacc | aaaa | Not used | Not used | Used |

| TAA 15 | ab | bbcc | bbcc | bbdd | Used | Not used | Not used |

| TAA 41 | ab | bbcc | aadd | aadd | Used | Not used | Used |

| Probability of identity between zygotic and nucellar genotypes | 4 × 10−6 | 0 | 1 × 10−5 | ||||

| Probability of identity between two independent zygotic genotypes | 1 × 10−3 | 2 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−3 | ||||

From the 13 SSR markers analysed, seven were used for genetic analysis of plants recovered via in vitro nucellus culture from intergeneric hybridizations between ‘Clemenules’ clementine and ‘Fortune’ mandarin by P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’. These markers clearly differentiated parents with specific alleles of P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’ male parent. The likelihood of identity between nucellar and zygotic plants was therefore nil. The probability of identity between two independent zygotes was 5 × 10−3 for clementine and ‘Fortune’ mandarin × P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’, calculated as described above.

Hybridizations 2x × 4x

Fruit- and seed-set, embryo rescue and ploidy level of recovered plants

Different 2x × 4x hybridizations were performed to study the formation of polyembryonic seeds in 2x × 4x hybridizations in the non-apomictic citrus genotypes (Table 3). Developed and undeveloped seeds were obtained in all hybridizations (Fig. 2A, B). The number of developed seeds varied between 0·2 and 2·1 per fruit (Table 3). Meanwhile, the number of undeveloped seeds was much higher (90 % of total seeds) than developed seeds in all hybridizations, varying between 3·4 and 10·8 per fruit.

Table 3.

Fruit-set, number and type of seeds obtained in 2x × 4x hybridizations

| Diploid female parent | Tetraploid male parent | No. of pollinated flowers | No. of fruits set | No. of developed seeds | Number of undeveloped seeds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fina | Nova | 50 | 39 | 7 | 242 |

| Clemenules | Nova | 25 | 13 | 5 | 124 |

| Hernandina | Nova | 80 | 38 | 15 | 218 |

| Bruno | Pineapple | 100 | 65 | 47 | 282 |

| Tomatera | Pineapple | 150 | 60 | 14 | 204 |

| Fina | Orlando | 50 | 46 | 24 | 499 |

| Clemenules | Orlando | 100 | 75 | 159 | 742 |

Fig. 2.

(A) Developed seeds obtained in 2x × 4x hybridizations. (B) Undeveloped seeds obtained in 2x × 4x hybridizations. (C) Multiple embryos contained in undeveloped seeds. (D) Monoembryonic undeveloped seed. (E,F) Germination of multiple embryos from undeveloped seeds.

In all hybridizations, undeveloped seeds had either one (monoembryonic) or multiple embryos (polyembryonic) (Fig. 2C, D). Embryos were at globular to early cotyledonary stage and variable in size (macroscopically some embryos were so small that they were difficult to identify, whereas others reached a size of approx. 3 mm). In polyembryonic seeds, embryos were highly compacted and sometimes surrounded by endosperm traces, which made it practically impossible to individualize and count them accurately, without damaging them. Consequently, all embryos of a single seed were cultivated together (Table 4, Fig. 2E, F). The smallest proportion (20 %) of polyembryonic seeds corresponded to the pollination between ‘Clemenules’ clementine and tetraploid ‘Nova’ mandarin, whereas the hybridization between ‘Tomatera’ clementine and tetraploid ‘Pineapple’ sweet orange gave the highest proportion of polyembryonic seeds (48 %).

Table 4.

In vitro culture of embryos obtained in undeveloped seeds produced in 2x × 4x hybridizations

| Diploid female parent | Tetraploid male parent | No. of monoembryonic seeds | No. of polyembryonic seeds | No. of germinated embryos | No. of germinated embryos per polyembryonic seed | No. of triploid plants per polyembryonic seed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fina | Nova | 95 | 33 | 162 | 2·0 | 1·3 |

| Clemenules | Nova | 71 | 18 | 105 | 1·9 | 1·5 |

| Hernandina | Nova | 47 | 13 | 74 | 2·1 | 1·5 |

| Bruno | Pineapple | 46 | 24 | 92 | 1·9 | 1·5 |

| Tomatera | Pineapple | 84 | 78 | 276 | 2·5 | 1·9 |

| Fina | Orlando | 110 | 70 | 278 | 2·4 | 0·8 |

| Clemenules | Orlando | 221 | 199 | 632 | 2·1 | 1·0 |

The average number of embryos that germinated from each polyembryonic seed ranged from 1·9 to 2·5 (Table 4). The highest number of regenerated plants per polyembryonic seed was 1·9 in the hybridization between ‘Tomatera’ clementine and tetraploid ‘Pineapple’ sweet orange (Table 4). All the regenerated plants were triploid.

Additionally, ‘Fina’ and ‘Clemenules’ clementines were pollinated with diploid ‘Nova’ mandarin to confirm the premise that the male parent was not responsible for producing multiple embryos in 2x × 4x hybridizations. Citrus genotypes are known to occasionally produce unreduced megagametophytes, giving rise to triploid embryos in 2x × 2x hybridizations (Cameron and Frost, 1968). In such hybridizations, the size of seeds with triploid embryos was reduced to such an extent that they could be visually distinguished from normal seeds (Fig. 3). At maturity they were fully developed and one-third to one-sixth of the size of normal seeds (Esen and Soost, 1971a). All the small seeds obtained contained only one embryo and regenerated only one plant per embryo and the ploidy level of all plants was triploid (Table 5).

Fig. 3.

Types of seeds obtained in 2x × 2x hybridization. (A) Developed small seeds with triploid embryos. (B) Normal seeds.

Table 5.

Fruit-set, number, seeds, plants and ploidy level obtained in 2x × 2x hybridizations

| Female parent | Male parent | Number pollinated flowers | Number of fruit set | Number small seeds | Number cultured embryos | Number regenerated plants | Number triploid plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fina | Nova | 200 | 148 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Clemenules | Nova | 100 | 70 | 25 | 25 | 22 | 22 |

Genetic analysis

To determine the genetic origin of triploid plants recovered from germination of multiple embryos contained in the same undeveloped seed from 2x × 4x hybridizations, 46 triploid plants corresponding to 13 different seeds and their parents were analysed with eight heterozygotic SSR markers for clementine (Table 2). These included the following subsets of triploids: 16 triploid plants originating from five different undeveloped seeds obtained from hybridizations between clementines and tetraploid ‘Nova’ mandarin; 13 triploid plants originating from four different undeveloped seeds from hybridizations between clementines and tetraploid ‘Orlando’ tangelo; and 17 triploid plants obtained from four different undeveloped seeds produced by hybridizations between clementines and tetraploid ‘Pineapple’ sweet orange.

The same profile was revealed for all triploid plants obtained from the same seed; moreover, it was possible to differentiate all plants regenerated from different seeds and hybridizations (Fig. 4). As an example, Fig. 5 shows the profiles of triploid plants recovered from hybridization between clementines and tetraploid ‘Orlando’ tangelo with the Ci02B07 SSR marker. Clementines displayed two alleles of 162 and 164 nt whereas tetraploid ‘Orlando’ tangelo presented two alleles of 160 and 170 nt. Plants 3, 4 and 5 (corresponding to the same seed) and 14 and 15 (plants from the same seed) showed the same profiles, which comprised two alleles of 160 and 170 nt coming from tetraploid ‘Orlando’ tangelo and one allele of 162 nt corresponding to clementine. Plants 6–13 (corresponding to two different seeds) displayed the same profile, comprising one allele of 160 nt coming from tetraploid ‘Orlando’ tangelo and one allele of 164 nt from clementine.

Fig. 4.

Cluster analysis of SSR data from 2x × 4x progenies based on the neighbour-joining method and Dice dissimilarity. (A) Triploid plants obtained from undeveloped seeds originating from the pollinations between diploid clementines ‘Fina’ (Fin), ‘Hernandina’ (Her), ‘Clemenules’ (Nul) and tetraploid ‘Nova’ mandarin (Nov) male parent. (B) Triploid plants obtained from undeveloped seeds originating from pollinations between diploid clementines (Fin, Nul) and tetraploid ‘Orlando’ tangelo (Orl) male parent. (C) Triploid plants obtained from undeveloped seeds originating from the pollinations between diploid clementines ‘Bruno’ (Bru), ‘Tomatera’ (Tom) and tetraploid ‘Pineapple’ sweet orange (Pin) male parent.

Fig. 5.

Genetic analysis of clementine by tetraploid ‘Orlando’ tangelo with Ci02B07 SSR marker. Genotypes: 1, clementine; 2, tetraploid ‘Orlando’ tangelo; 3–5 and 6–9, triploid hybrids obtained from two different undeveloped seeds originating from the hybridization between ‘Fina’ clementine and tetraploid ‘Orlando’ tangelo; 10–13, triploid hybrids obtained from the same undeveloped seed originating from the hybridization between ‘Clemenules’ clementine and tetraploid ‘Orlando’ tangelo; 14 and 15, triploid hybrids obtained from the same undeveloped seed originating from the hybridization between ‘Fina’ clementine and tetraploid ‘Orlando’ tangelo; C, PCR negative control.

Hybridizations 2x × 2x

Fruit- and seed-set, nucellus culture in vitro, embryo rescue and ploidy level of recovered plants

Different 2x × 2x hybridizations were performed to study in vitro embryogenesis from isolated nucelli of non-apomictic citrus genotypes. In the hybridizations between ‘Clemenules’ clementine and ‘Fortune’ mandarin with P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’, fruits were collected 13–15 weeks after pollination. In the hybridization between ‘Clemenules’ clementine and P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’, 49 fruits were used, which contained 550 seeds (11·2 seeds per fruit). In hybridization between ‘Fortune’ mandarin and P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’, 19 fruits were used, which contained 175 seeds (9·2 seeds per fruit) (Table 6). The seeds collected were well developed (Fig. 1A).

Table 6.

In vitro culture of nucellus isolated from seeds obtained in 2x × 2x hybridizations; ploidy level of plants obtained

| Female parent | Male parent | No. of pollinated flowers | No. of used fruits | No. of seeds obtained | No. of cultured nucellus | No. of developed nucellus | No. of embryos obtained | No. of plant analysed | No. of diploid plants | No. of triploid plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clemenules | Benecke | 106 | 49 | 550 | 529 | 98 | 422 | 263 | 260 | 3 |

| Fortune | Benecke | 100 | 19 | 175 | 151 | 27 | 131 | 65 | 54 | 11 |

Nucellus culture in vitro produced embryos, initially by a process of direct embryogenesis and later by a process of adventive embryogenesis (Fig. 6A, B). From the hybridization between ‘Clemenules’ clementine and P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’, 550 normal seeds were obtained and 529 nucelli were isolated and cultivated (Table 6). From the 550 normal seeds, eight had more than one embryo (1·5 %) and 13 did not have any embryos and were eliminated. Ninety-eight nucelli (19·0 %) developed, producing a total of 422 embryos, from which 327 plants were regenerated. All plants obtained had trifoliate leaves (Fig. 6C, D). In parallel, 529 isolated embryos were rescued from the same seeds and cultivated in vitro. Seventy-four (14·0 %) germinated, producing plants with trifoliate leaves (Table 7). Finally, we obtained plants from the isolated zygotic embryos and corresponding nucelli from 57 seeds.

Fig. 6.

(A,B) Nucellus cultured in vitro with embryo development in the micropilar region. (C) Germination of embryos obtained from nucellus cultured in vitro. (D) Regenerated plants from embryos produced by nucellus cultured in vitro, showing trifoliate leaves.

Table 7.

Embryo rescue from seeds obtained in 2x × 2x hybridizations

| Female parent | Male parent | Number obtained seeds | Number of seeds with embryo | Number cultured embryos | Number germinated embryos | Number analysed plants | Number diploid plants | Number triploid plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clemenules | Benecke | 550 | 529 | 529 | 74 | 66 | 65 | 1 |

| Fortune | Benecke | 175 | 151 | 151 | 22 | 21 | 18 | 3 |

From the hybridization between ‘Fortune’ mandarin with P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’, 175 normal seeds were obtained (Table 6). From these seeds, 151 nucelli were isolated and cultivated; the remaining 24 seeds without embryos were discarded. Twenty-seven (18·0 %) developed. A total of 131 embryos were obtained and 93 plants were regenerated, all of which displayed trifoliate leaves (Table 6). At the same time, 151 embryos were rescued from the same seeds and cultivated in vitro. Twenty-two (14·6 %) germinated and produced plants with trifoliate leaves (Table 7). Ultimately, we obtained plants from the isolated zygotic embryos and corresponding nucelli from 11 seeds.

From among the 263 plants obtained from nucellus culture in vitro of ‘Clemenules’ clementine seeds, 260 were diploid (98·9 %) and three (1·1 %) were triploid (Table 6). Of the 66 plants obtained from germination of isolated zygotic embryos, 65 were diploid (98·5 %) and one was triploid (1·5 %) (Table 7). The three triploid plants regenerated from the nucellus culture in vitro and the triploid plant obtained from germination of the isolated embryo belonged to the same seed.

From among the 65 plants obtained from nucellus culture in vitro of ‘Fortune’ mandarin seeds, 54 were diploid (83·1 %) and 11 (16·9 %) were triploid (Table 6). Among the 21 plants obtained from the germination of the isolated zygotic embryos, 18 were diploid (85·7 %) and three were triploid (14·3 %) (Table 7). The 11 triploid plants regenerated from the nucellus culture in vitro and the three triploid plants obtained from germination of the embryos isolated inside nucelli belonged to three different seeds.

Genetic analysis

To determine the genetic origin of plants regenerated from nucellus culture in vitro, seven SSR markers, which are heterozygotic for clementine and ‘Fortune’ mandarin, were employed. We analysed (1) 53 diploid plants and four triploid plants obtained in the hybridization between ‘Clemenules’ clementine and P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’, corresponding to ten different seeds; and (2) 22 diploid plants and 14 triploid plants corresponding to seven different seeds obtained in the hybridization between ‘Fortune’ mandarin and P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’. All plants analysed had trifoliate leaves and all plants corresponding to the same seed displayed identical profiles for all hybridizations at diploid and triploid level. It was possible to differentiate all the groups studied. The cluster analysis (Fig. 7) clearly demonstrates that identical profiles were found for all seeds corresponding to the plant obtained from the zygotic embryo and plants recovered from nucellus culture in vitro. Results with the Mest 419 SSR marker are shown as an example in Fig. 8. ‘Clemenules’ clementine showed two alleles of 108 and 120 nt whereas P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’ displayed one allele of 102 nt. All plants from seeds 1, 4, 5, 8 and 9 presented a 108-nt allele of ‘Clemenules’ clementine and 102-nt allele of P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’. The other groups showed an allele of 120 nt of ‘Clemenules’ clementine and the 102-nt allele of P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’.

Fig. 7.

Cluster analysis of SSR data from 2x × 2x progenies based on the neighbour-joining method and Dice dissimilarity. NulBec and ForBec correspond to plants recovered from nucellus culture in vitro obtained in the pollinations between ‘Clemenules’ clementine (Nul) and ‘Fortune’ mandarin (For) with P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’ (Bec). The first number indicates different seeds and in parentheses are the ploidy level of plants obtained from zygotic embryo and number and ploidy level of plants recovered from nucellus culture in vitro.

Fig. 8.

Genetic analysis with Mest 419 SSR marker of diploid plants obtained from nucellus culture in vitro and germination of zygotic embryo produced in ‘Clemenules’ clementine and P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’ hybridization. Z, plant obtained from germination of zygotic embryo; the other profiles of each group correspond to plants obtained from nucellus culture in vitro. Cl, ‘Clemenules’ clementine; P, P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’.

Histology

Twenty-seven seeds obtained from hybridization between ‘Clemenules’ clementine and P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’ were analysed at different developmental stages. The presence of a single embryo was observed in all seeds (Fig. 9A) except one (Fig. 9B), in which a dominant embryo and other small embryos were found in the micropilar region of the seed.

Fig. 9.

Histological section of seeds obtained in ‘Clemenules’ clementine by P. trifoliata ‘Benecke’ hybridization and sections stained by PAS. (A) Seed fixed 100 d after pollination. (B) Seed fixed 80 d after pollination. E, zygotic embryo; Ed, dominant embryo; Es, secondary embryo; En, endosperm; N, nucellus; Te, outer integument; Ti, inner integument.

DISCUSSION

SSR markers are highly efficient at determining the origin of embryos in interspecific crosses

All clementines were identical but important polymorphism was found between clementines and all the genotypes used as male parents. In citrus, SSR markers can easily distinguish between species or cultivars arising from sexual hybridization (Barkley et al., 2006; Luro et al., 2008). Conversely, differentiation of genotypes arising from spontaneous mutations is very difficult, as in the case of clementines (Bretó et al., 2003) or sweet oranges (Fang and Roose, 1997). By using several heterozygous markers differentiating the male and female parents, we also found good probability of differentiation between independent zygotic plants.

Multiple embryos, produced in undeveloped seeds arising from hybridizations between diploid non-apomictic citrus genotypes and tetraploid pollen, are the result of zygotic embryo cleavage

Thirty-nine per cent of the undeveloped seeds produced more than one embryo per seed and genetic analysis demonstrated that all plants obtained from the same undeveloped seed were identical and of hybrid origin. Our results therefore confirm the proposal made by Oiyama and Kobayashi (1990) after analysis of 2x × 4x progeny with just a single isozyme marker. Consequently, it is clear that these plants resulted from cleavage of the original zygotic embryo (Bacchi, 1943), rather than the presence of two or more functional embryo sacs in a single ovule. Indeed, with the selected markers, the probability of finding two independent zygotic embryos with the same profile was very low.

Seed polyembryony of non-apomictic citrus genotypes is specifically induced by pollination with a tetraploid male parent

We have studied plants regenerated from 2x × 4x hybridizations using three different tetraploid male parents. Polyembryony arising from the original zygotic embryo occurred in every case, eliminating the influence of a specific male parent genotype and demonstrating the link between interploid hybridization (2x × 4x) and multiple embryo development. In addition, within our triploid breeding programme, we have performed more than 50 different 2x × 4x hybridizations and observed the presence of multiple embryos inside the same seed in all of them. Furthermore, in the same hybridizations, but between two diploid parents, polyembryony was never observed in small seeds resulting from the fertilization of a diploid unreduced megagametophyte by haploid pollen (Cameron and Frost, 1968). Moreover, no polyembryonic seeds were observed in the different 2x × 4x crosses performed in the framework of our triploid breeding programme (our unpubl. res.). These observations support the fact that multiple embryo production in undeveloped seeds is not a consequence of parental genotype or embryo ploidy but a consequence of male parent ploidy and thus male parent genotype excess at endosperm or embryo level. Esen and Soost (1971b, 1977) have proposed that in this type of hybridization the ratio of ploidy level between embryo and endosperm (3/4) generates an incompatibility between the two, and an abnormal development of endosperm followed by underdevelopment of the embryos. It is possible that these unfavourable conditions for the development of the initial zygotic embryo affect its dominance, thereby allowing the production of additional embryos from proembryonic cells derived from the original zygotic embryo. Another hypothesis could be raised related to the parent-of-origin effect. Parent-of-origin effects generate phenotypes that depend on the direction of a cross and occur frequently during angiosperm seed development, where maternal influence is most common (Alleman and Doctor, 2000). Genetic mechanisms can contribute to parent-of-origin effects during seed development, including the disproportionate maternal contribution to the endosperm, plastidic and cytoplasmic inheritance, expression of genes in the gametophytes and gametes, and differential expression of parental alleles in the developing seed (Dilkes and Comai, 2004). In interploidy and interspecific crosses tested in model organisms such as maize and Arabidopsis, genetic and phenotypic changes observed in the progenies can be explained as a consequence of the parent-of-origin effect.

Plants recovered by in vitro nucellus culture from non-apomictic citrus genotypes are zygotic and not nucellar plants

Genetic analysis of plants obtained from nucellus culture in vitro and plants recovered from the corresponding zygotic embryo of the same seed demonstrated that all plants obtained from nucellus culture of clementine and ‘Fortune’ mandarin originated from the zygotic embryo and not from the nucellus. The present data suggest that proembryonic cells are formed in the micropilar region as a result of original zygotic embryo cleavage. Elimination of the original zygotic embryo and the culture in vitro of the nucellus containing the zygotic proembryogenic cells allow these to complete development producing embryos. The histological study of developing seeds did not reveal the presence of proembryonic cells, and only the zygotic embryo was observed. Only in one case did we find multiple embryos, but these probably corresponded to the rare cases where twin embryos are formed in vivo (Ozsan, 1964; Cameron and Garber, 1968). Esan (1973) made a comprehensive histological study of in vivo development of citron seeds and obtained similar results. Esan only found evidence of zygotic embryo development and only in one case did he observe several proembryos in the same seed; however, all surviving in vitro nucellus cultures produced new embryos after the zygotic embryo was discarded. The failure to observe the proposed proembryonic cells in the histological study may have been due to their low level of differentiation, which does not enable proper identification with the procedures used.

The total lack of regenerated plants with maternal genotype indicates that nucellar cells of clementine and ‘Fortune’ mandarin do not have embryogenic capacity either in vivo or in vitro, in contrast to nucellar cells of apomictic genotypes (Button and Bornman, 1971; Kobayashi et al., 1981).

Our results for clementine and ‘Fortune’ mandarin are in agreement with observations made of plants from non-apomictic genotypes previously produced by nucellus culture in vitro. Rangan et al. (1968) regenerated plants of pummelo, ‘Ponderosa’ lemon and ‘Temple’ mandarin (C. temple Hort. ex Y. Tan.) and Esan (1973) regenerated plants of citron. Phenotypic observations indicated that none of the plants produced by nucellus culture in vitro maintained the maternal phenotype (C. N. Roistacher, University of California, Riverside, USA, pers. comm.). Navarro et al. (1985) also regenerated plants of several clementine varieties from nucellus culture in vitro with a view to producing healthy vigorous nucellar plants. The detailed phenotypic characterization of these plants in the greenhouse revealed morphological similarity among plants obtained from the same nucellus, but phenotypic diversity between plants arising from different nucelli, while the majority of plants differed from the maternal genotypes. The isoenzymatic analysis confirmed the phenotypical data. Long-term field evaluation of the plants showed that none of them maintained the maternal genotype (data not published).

All the available data support our conclusion that plants of non-apomictic citrus genotypes produced by nucellus culture in vitro arise from somatic embryogenesis of zygotic cells and not from nucellar cells, as previously believed.

Adventitious polyembryony in non-apomictic citrus genotypes

Many angiosperms and gymnosperms have the potential for monozygotic cleavage embryony (Durzan, 2008). In normal seed development of conifers usually only one embryo dominates while the others remain undeveloped at the base of the seed (Durzan, 2008). In Sequoia sempervirens and Actinostrobus acuminatus, cell strands in the zygote stratify to form several embryos. The distribution of free nuclei in the zygote determines their subsequent segregation into rudiments of new sporophytes (Batygina and Vinogradova, 2007). In Torreya, Cephalotaxus, Ephedra and Gnetum (Johansen, 1950) embryogenesis from the suspensor cells is also possible and the formation of a special membrane around the zygote gives rise to embryos in Gnetum and Ephedra (Teryokhin, 1991, cited by Batygina and Vinogradova (2007)). The potential for cleavage polyembryony in conifers is used to develop seeds artificially. Monozygotic cleavage embryony was described in the genus Paeonia, in which somatic embryos arise from a multinucleated cell structure.

In species producing monoembryonic seeds usually only one embryo remains in a mature seed as the result of competitive development, while the other dies during the early stages (Batygina, 1989, 1998, 2006). Competition between embryos has been described in apomictic citrus genotypes where zygotic embryos develop more slowly than nucellar embryos (Koltunow, 1993). In polyembryonic citrus seeds the favoured development of nucellar embryos could be due to an earlier initiation of embryogenesis and to the competition for available nutrients (Wakana and Uemoto, 1987, 1988). In the non-apomictic citrus genotypes such competition should also explain the differences in development between the original zygotic embryo and the adventitious one. A late initiation of secondary embryo formation could explain the complete development of only one embryo. However, another hypothesis could relate to hormonal dominance of the initial zygotic embryo or an inhibition of adventitious embryo development. This kind of hormonal inhibition of embryogenesis was proposed by Tisserat and Murashige (1977a), who demonstrated that the presence of ovules of the non-apomictic citron inhibited the in vitro embryogenetic process from embryogenic callus of the apomictic ‘Ponkan’ mandarin (C. reticulata). Moreover, the same authors have shown that endogenous levels of indolacetic acid, abcisic acid and gibberellin were much higher in citron than in the mandarin ovules (Tisserat and Murashige, 1977b).

Practical implications for citrus breeding and sanitation

Our conclusions have important implications for triploid breeding programmes based on 2x × 4x hybridizations (Starrantino and Recupero, 1981; Navarro et al., 2002; Yoshida et al., 2003) as during the stages of embryo rescue from multiple embryos contained in undeveloped seeds it is necessary to regenerate only one plant per seed. This is of enormous practical value because it significantly reduces the workload during the in vitro stage and avoids costly and lengthy field evaluation of several plants belonging to the same genotype.

Moreover, nucellus culture was previously considered suitable for producing pathogen-free plants and the technique was specifically recommended for this purpose (Soost and Cameron, 1975). Our results clearly demonstrate that no true-to-type plant with maternal genotype can be obtained by non-apomictic nucellus culture. Coincidentally, interest in this technique has declined since the same research team introduced the shoot-tip grafting in vitro technique to produce pathogen-free plants without juvenile traits (Navarro et al., 1975), which has been adopted worldwide (Navarro and Juárez, 2007). However, during the last decade, somatic hybridization sparked interest in the induction of embryogenic callus lines of non-apomictic genotypes via nucellus or ovule culture in vitro (Wu et al., 2005). It is clear that accurate molecular studies of the induced calli will be necessary to confirm their maternal origin.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that in non-apomictic citrus genotypes, embryogenic cells or proembryos are formed by cleavage of the zygotic embryo. Moreover, the development of these adventitious cells or embryos can take place in vivo and in vitro as the result of two different mechanisms that prevent the dominance of the initial zygotic embryo. The first mechanism involves the mechanical elimination of the dominant zygotic embryo and subsequent culture in vitro of the nucellus, thus facilitating the development of embryos from embryogenic cells deriving from the zygotic embryo. The second is associated with interploidy 2x × 4x hybridizations.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was financed by the AGL2008-00596-MCI and Prometeo 2008/121 Generalidad Valenciana projects. We thank Carmen Ortega and María Hernández for their technical assistance in the laboratory and J. A. Pina for growing plants in the greenhouse.

LITERATURE CITED

- Alleman M, Doctor J. Genomic imprinting in plants: observations and evolutionary implications. Plant Molecular Biology. 2000;43:147–161. doi: 10.1023/a:1006419025155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleza P, Juárez J, Hernández M, Pina JA, Ollitrault P, Navarro L. Recovery and characterisation of a Citrus clementina Hort. ex Tan. ‘Clemenules’ haploid plant selected to establish the reference whole citrus genome sequence. BMC Plant Biology. 2009 doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-110. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-9-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi O. Cytological observations in citrus III. Megaesporogenesis, fertilization and polyembryony. Botanical Gazette. 1943;105:221–225. [Google Scholar]

- Batygina TB. New approach to the system of reproduction in flowering plants. Phytomorphology. 1989;39:311–325. [Google Scholar]

- Batygina TB. Morphogenesis of somatic embryos developing in natural conditions. Biologija. 1998;3:61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Batygina TB. Embryoidogeny, Embryology of Flowering Plants. Terminology and Concepts, vol. 2. Seed. Enfield:: Plymouth Sci. Pub; 2006. pp. 403–409. [Google Scholar]

- Batygina TB, Vinogradova GY. Phenomenon of polyembryony. Genetic heterogenity of seeds. Russian Journal of Developmental Biology. 2007;38:126–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley NA, Roose ML, Krueger RR, Federici CT. Assessing genetic diversity and population structure in a citrus germplasm collection utilizing simple sequence repeat markers (SSRs) Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2006;112:1519–1531. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0255-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benbouzas H, Jacquemin JM, Baudoin JP, Mergeai G. Optimization of a reliable, fast, cheap and sensitive silver staining method to detect SSr markers in polyacrylamide gels. Biotechnology, Agronomy, Society and Environment. 2006;10:77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bretó MP, Ruíz C, Pina JA, Asins MJ. The diversification of Citrus clementina Hort. Ex Tan., a vegetatively propagated crop species. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2003;21:285–293. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2001.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button J, Bornman CH. Development of nucellar plants from unfertilised ovules of the Washington Navel orange through tissue culture. The Citrus Grower and Subtropical Fruit Journal. 1971;September:11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JW, Frost HB. Genetic, breeding and nucellar embryony. In: Reuther W, Batchelor LD, Webber HJ, editors. The citrus industry. Riverside: University of California; 1968. pp. 325–370. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JW, Garber M. Identical twin-hybrids of Citrus × Poncirus from strictly sexual seed parents. American Journal of Botany. 1968;55:199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Dellaporta J, Hicks JB. A plant DNA minipreparation version II. Plant Molecular Biology Reports. 1983;1:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dilkes P, Comai L. A differential dosage hypothesis for parental effects in seed development. The Plant Cell. 2004;16:3174–3180. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.161230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durzan DJ. Monozygotic cleavage polyembryogenesis and conifer tree improvement. Cytology and Genetics. 2008;42:159–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esan EB. A detailed study of adventive embryogenesis in the Rutaceae. 1973. PhD thesis, University of California, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Esen A, Soost RK. Unexpected triploids in Citrus: their origin, identification and possible use. Journal of Heredity. 1971a;62:329–333. [Google Scholar]

- Esen A, Soost RK. Tetraploid progenies from 2x – 4x crosses of Citrus and their origin. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. 1971b;97:410–414. [Google Scholar]

- Esen A, Soost RK. Proceedings First mondial Congress of Citriculture. Valencia: International Society of Citriculture; 1977. Relation of unexpected polyploids to diploid megagametophytes and embryo endosperm ploidy ratio in Citrus; pp. 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fang DQ, Roose ML. Identification of closely related citrus cultivars with inter-simple sequence repeat markers. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1997;95:408–417. [Google Scholar]

- Froelicher Y, Bassene JP, JedidI-Neji E, et al. Induced parthenogenesis in mandarin induction procedures and genetic analysis of plantlets. Plant Cell Reports. 2007;26:937–944. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0314-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froelicher Y, Dambier D, Bassene JB, et al. Characterization of microsatellite markers in mandarin orange (Citrus reticulata Blanco) Molecular Ecology Resources. 2008;8:119–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost HB. Polyembryony, heterozygosis and chimeras in Citrus. Hilgardia. 1926;1:365–402. [Google Scholar]

- Frost HB. The genetics and cytology of Citrus. Current Science. 1938:24–27. (Special Number on Genetics) [Google Scholar]

- Frost HB, Soost RK. Seed reproduction, development of gametes and embryos. In: Reuther W, Batchelor LD, Webber HB, editors. The citrus industry. Vol. 2. Berkeley: University of California; 1968. pp. 290–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss RD. A microchemical reaction resulting in the staining of polysaccharide structures in fixed tissue preparations. Archives of Biochemistry. 1948;16:131–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias L, Lima H, Simon JP. Isoenzyme identification of zygotic and nucellar seedlings in citrus. Journal of Heredity. 1974;65:81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen DA. Plant embryology. Waltham, MA: Chronica Botanica Comp; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Kepiro JL, Roose ML. Nucellar embryony. In: Khan IA, editor. Citrus genetics, breeding and biotechnology. Wallingford: CABI; 2007. pp. 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kepiro JL, Roose ML. AFLP markers closely linked to a major gene essential for nucellar embryony (apomixis) in Citrus maxima × Poncirus trifoliata. Tree Genetics & Genomes. 2010;6:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Khan IA, Roose ML. Frequency and characteristics of nucellar and zygotic seedlings in three cultivars of trifoliate orange. Journal of American Society for Horticultural Science. 1988;113:105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kijas JMH, Thomas MR, Fowler JCS, Roose ML. Integration of trinucleotide microsatellites into a linkage map of Citrus. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1997;94:701–706. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S, Ieda I, Nakatani M. Proceedings of 4th International Citrus Congress. Tokyo: International Society of Citriculture; 1981. Role of the primordium cell in nucellar embryogenesis in citrus; pp. 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Koltunow AM. Apomixis embryo sacs and embryos formed without meiosis or fertilization in ovules. The Plant Cell. 1993;5:1425–1437. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.10.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luro F, Laigret F, Bove JM. DNA amplified fingerprinting, a useful tool for determination of genetic-origin and diversity analysis in citrus source. HortScience. 1995;30:1063–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Luro F, Costantino G, Terol JF, et al. Transferability of the EST-SSRs developed on Nules clementine (Citrus clementina Hort ex Tan) to other Citrus species and their effectiveness for genetic mapping. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:287. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-287. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-9-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Filho HP, Bordignon R, Lizana-Ballve RM, Siquiera WJ. Genetic proof of the occurrence of mono and dizygotic hybrid twins in citrus rootstocks. Revista Brasileira Genetica. 1993;16:703–711. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Plantarum. 1962;15:473–479. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro L, Juárez J. Shoot-tip grafting in vitro. In: Khan IA, editor. Citrus genetics, breeding and biotechnology. Wallingford: CABI; 2007. pp. 353–364. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro L, Roistacher CN, Murashige T. Improvement of shoot-tip grafting in vitro for virus-free citrus. Journal of American Society and for Horticultural Science. 1975;100:471–479. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro L, Ortiz J, Juárez J. Aberrant citrus plants obtained by somatic embryogenesis of nucellus cultured in vitro. HortScience. 1985;20:214–215. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro L, Juárez J, Aleza P, Pina JA. Vasil IK. ed. Proceedings of the 10th IAPTC&B Congress, Plant Biotechnology 2002 and Beyond. Florida; 2002. Recovery of triploid seedless mandarin hybrids from 2n × 2n and 2n × 4n crosses by embryo rescue and flow cytometry; pp. 541–544. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolosi E, Deng ZN, Gentile A, La Malfa S, Continella G, Tribulato E. Citrus phylogeny and genetic origin of important species as investigated by molecular markers. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2000;100:1155–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Oiyama I, Kobayashi S. Polyembryony in undeveloped monoembryonic diploid seeds crossed with a citrus tetraploid. HortScience. 1990;25:1276–1277. [Google Scholar]

- Ollitrault P, Dambier D, Luro F, Froelicher Y. Ploidy manipulation for breeding seedless triploid citrus. Plant Breeding Reviews. 2008;20:323–354. [Google Scholar]

- Ozsan M. Studies in some monoembryonic citrus varieties for the purpose of achieving nucellar clones. 1964. PhD thesis, University of Ankara, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Perrier X, Jacquemoud-Collet JP. DARwin software. 2006 http//darwin.cirad.fr/darwin . [Google Scholar]

- Perrier X, Flori A, Bonnot F. Data analysis methods. In: Hamon P, Seguin M, Perrier X, Glaszmann JC, editors. Genetic diversity of cultivated tropical plants. Montpellier: Enfield, Science Publishers; 2003. pp. 43–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rangan TS, Murashige T, Bitters WP. In vitro initiation of nucelar embryos in monoembryonic citrus. HortScience. 1968;3:226–227. [Google Scholar]

- Roistacher CN. Proceedings of the International Society of Citriculture. University of California; 1979. Elimination of citrus pathogens in propagative budwood I. Budwood selection, indexing and thermotherapy; pp. 965–972. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz C, Breto MP, Asins MJ. A quick methodology to identify sexual seedlings in citrus breeding programs using SSR markers. Euphytica. 2000;112:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Savidan Y. Apomixis genetics and breeding. Plant Breeding Reviews. 2000;18:13–85. [Google Scholar]

- Soost RK, Cameron JW. Citrus. In: Janick J, Moore JN, editors. Advances in fruit breeding. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press; 1975. pp. 507–540. [Google Scholar]

- Starrantino A, Reforgiato-Recupero G. Proceedings 4th International Citrus Congress. International Society of Citriculture. Vol. 1. Tokyo: 1981. Citrus hybrids obtained in vitro from 2x females×4x males; pp. 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Strasburger E. Über Polyembryonie. Jena: Z. Naturwiss; 1878. [Google Scholar]

- Tisserat B, Murashige T. Probable identity of substances in citrus that repress asexual embryogenesis. In Vitro. 1977a;13:785–789. doi: 10.1007/BF02627858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisserat B, Murashige T. Repression of asexual embryogenesis in vitro by some plant growth regulators. In Vitro. 1977b;13:799–805. doi: 10.1007/BF02627860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakana A, Uemoto S. Adventive embryogenesis in citrus I. The occurrence of adventive embryos without pollination or fertilization. American Journal of Botany. 1987;74:517–530. [Google Scholar]

- Wakana A, Uemoto S. Adventive embryogenesis in citrus (Rutaceae) II. Postfertilization development. American Journal of Botany. 1988;75:1033–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers LG, Calavan EC. Nucellar embryony as a means of freeing citrus clones of virus diseases. In: Wallace JM, editor. Citrus virus diseases. Berkeley: University of California; 1959. pp. 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Wu JH, Ferguson AR, Mooney PA. Allotetraploid hybrids produced by protoplast fusion for seedless triploid Citrus breeding. Euphytica. 2005;141:229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Nesumi H, Yoshioka T, et al. New kumquat cultivar ‘Puchimaru’. Bulletin of the National Institute of Fruit Tree Science. 2003;2:9–16. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.