Abstract

Background and Aims

Annonaceae are one of the largest families of Magnoliales. This study investigates the comparative floral development of 15 species to understand the basis for evolutionary changes in the perianth, androecium and carpels and to provide additional characters for phylogenetic investigation.

Methods

Floral ontogeny of 15 species from 12 genera is examined and described using scanning electron microscopy.

Key Results

Initiation of the three perianth whorls is either helical or unidirectional. Merism is mostly trimerous, occasionally tetramerous and the members of the inner perianth whorl may be missing or are in double position. The androecium and the gynoecium were found to be variable in organ numbers (from highly polymerous to a fixed number, six in the androecium and one or two in the gynoecium). Initiation of the androecium starts invariably with three pairs of stamen primordia along the sides of the hexagonal floral apex. Although inner staminodes were not observed, they were reported in other genera and other families of Magnoliales, except Magnoliaceae and Myristicaceae. Initiation of further organs is centripetal. Androecia with relatively low stamen numbers have a whorled phyllotaxis throughout, while phyllotaxis becomes irregular with higher stamen numbers. The limits between stamens and carpels are unstable and carpels continue the sequence of stamens with a similar variability.

Conclusions

It was found that merism of flowers is often variable in some species with fluctuations between trimery and tetramery. Doubling of inner perianth parts is caused by (unequal) splitting of primordia, contrary to the androecium, and is independent of changes of merism. Derived features, such as a variable merism, absence of the inner perianth and inner staminodes, fixed numbers of stamen and carpels, and capitate or elongate styles are distributed in different clades and evolved independently. The evolution of the androecium is discussed in the context of basal angiosperms: paired outer stamens are the consequence of the transition between the larger perianth parts and much smaller stamens, and not the result of splitting. An increase in stamen number is correlated with their smaller size at initiation, while limits between stamens and carpels are unclear with easy transitions of one organ type into another in some genera, or the complete replacement of carpels by stamens in unisexual flowers.

Keywords: Annonaceae, basal angiosperms, Magnoliales, androecium, carpel, doubling, floral ontogeny, merism, perianth, reduction, secondary increase

INTRODUCTION

The Annonaceae are a large pantropical family of approx. 128 genera with over 2000 species, more than 900 of which are found in the Neotropics (Cronquist, 1981; Kessler, 1993). The family includes trees, shrubs and lianas, found in almost all vegetation types. It is generally considered to be a natural family and one of the six members of Magnoliales, as formalized by the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (2009), in which they remain one of the most important lineages in the early radiation of angiosperms (Sauquet et al., 2003). Annonaceae are closely related to both Magnoliaceae with similar floral construction (at least for the perianth), and Myristicaceae, with a comparable two-ranked leaf arrangement, extrorse anthers and ruminate endosperm. With a pantropical distribution, Annonaceae are morphologically highly diverse, and represent a significant part of plant diversity, both in terms of numbers of species and individuals.

The floral construction of most members of the family is characterized by a cyclic perianth of three trimerous whorls, an androecium of numerous stamens, and a gynoecium of more or less numerous free carpels on a flat or conical receptacle. Studies on flower ontogeny in this family are crucial for understanding the floral morphology and thus the systematic relationships between Annonaceae and other families in Magnoliales.

Despite the wide interest in this important family, the organogenesis of the flower has been carried out in very few species [e.g. Monodora crispata (Leins and Erbar, 1980, 1982, 1996), Annona montana, A. cherimola, A. muricata, Artabotrys hexapetala and Polyalthia suberosa (Leins and Erbar, 1996), Annona montana, Cananga odorata and Polyathia glauca – young carpel development only (van Heel, 1981), Artabotrys hexapetalus and Annona montana – androecium only (Endress, 1986, 1987, 1990), Rollinia deliciosa, Annona muricata and A. cherimola × A.squamosa (Moncur, 1988), Monanthotaxis whytei (Ronse De Craene and Smets, 1990, 1991) and Polyalthia suberosa – androecium only (Ronse De Craene and Smets, 1996)]. Earlier studies reported a relative homogeneity in perianth and androecium development, with an arrangement of the outer stamens or staminodes as three pairs (e.g. Ronse De Craene and Smets, 1990; Leins and Erbar, 1996). While perianth number is relatively constant, there is a high fluctuation in stamen and carpel number, and it remains unclear what the plesiomorphic condition is. Ronse De Craene and Smets (1990, 1996) insisted that a trimerous arrangement of successive stamen and carpel whorls makes up the plesiomorphic arrangement, with either a further reduction of whorls or an increase in stamens and carpels by a reduction in their sizes. A whorled perianth has been reconstructed as ancestral in Magnoliales and possibly in basal angiosperms (Endress and Doyle, 2009). Magnoliaceae differ from Annonaceae in having a helical androecium and gynoecium and it is not certain whether this condition is ancestral. However, the significance of the occurrence of outer stamen pairs remains problematic, as it is widespread in basal angiosperms, monocots and basal eudicots (e.g. Ronse De Craene and Smets, 1996; Ronse De Craene et al., 2003) and has been given different explanations (Endress, 1987, 1994; Erbar and Leins, 1994; Staedler and Endress, 2009).

A flower developmental investigation can be used to identify new morphological characters as additional support to molecular phylogenetic results. In Annonaceae, knowledge of the floral development remains limited and concentrated on very few species. In this study, flower ontogeny of 16 mainly Asian taxa from 12 genera were examined in detail using scanning electron microscopy. The present ontogenetical knowledge is summarized and supplemented by new information, especially of early developmental stages of the perianth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Flower buds of 15 species and two different genotypes of Cananga odorata from Annonaceae, representing 12 genera were collected from April 2007 to July 2008, either from the Living Collections in the South China Botanical Garden or in the wild (Table 1). All the materials were fixed in formalin acetic alcohol (FAA: 70 % alcohol, formaldehyde and glacial acetic acid in a ratio of 90 : 5 : 5) and subsequently stored in 70 % alcohol. Buds were dehydrated in an ethanol series, and critica-point dried with a K850 critical-point dryer (Emitech, Ashford, Kent, UK). The dried materials were later coated with platinum using an Emitech K575 sputter coater (Emitech) and examined with a Supra 55 VP scanning electron microscope at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. A list of voucher specimens and collection data is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of taxa used for the study arranged in alphabetical order

| No. | Taxon | Provenance | Voucher |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alphonsea monogyna Merr. et Chun | SCBG | Xu 09054 (IBSC) |

| 2 | Annona glabra L. | SCBG | Xu 09067 (IBSC) |

| 3 | Annona squamosa L. | SCBG | Xu 09046 (IBSC) |

| 4 | Artabotrys hexapetalus (L.f.) Bhandari | SCBG | Xu 09059 (IBSC) |

| 5 | Cananga odorata (Lamk.) Hook. f. et. Thoms. | SCBG | Xu 09056 (IBSC) |

| 6 | Cananga odorata var. fruticosa (Craib) Sincl. | SCBG | Xu 09061 (IBSC) |

| 7 | Desmos chinensis Lour. | SCBG | Xu 09058 (IBSC) |

| 8 | Fissistigma retusum Rehd. | Zhaoqing, Guangdong, China | Mo 46820 (IBSC) |

| 9 | Mezzettiopsis creaghii Ridl. | Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, China | Yang (HITBC) |

| 10 | Miliusa chunii W.T. Wang | Guilin, Guangxi, China | Cao 01268 IBK |

| 11 | Miliusa sinensis Finet et Gagnep. | Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, China | Yang (HITBC) |

| 12 | Mitrephora maingayi Hook. f. et Thoms. | Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, China | Yang (HITBC) |

| 13 | Mitrephora thorelii Pierre | Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, China | Yang (HITBC) |

| 14 | Polyalthia suberosa (Roxb.) Thwaites | SCBG | Xu 09050 (IBSC) |

| 15 | Pseuduvaria indochinensis Merr. | Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, China | Yang (HITBC) |

| 16 | Uvaria microcarpa Champ. ex Benth. | SCBG | Xu 09065 (IBSC) |

Abbreviations: SCBG, South China Botanical Garden; IBSC, Herbarium, South China Botanical Garden; IBK, Herbarium, Guangxi Institute of Botany; HITBC, Herbarium, Xishuangbannan Tropical Botanical Garden, Academia Sinica.

RESULTS

Floral morphology

Flowers are inserted at the end of branches, directly on the trunk or on short shoots departing from the trunk. Flowers are strictly arranged in cymes in the family, often with a reduction to a single flower, and are subtended by a single broad bract. Flowers in Annonaceae are generally recognized by the relatively stable trimerous perianth in three whorls (Figs 1 and 2). The outer perianth whorl is usually three-parted, but the number of the middle and inner perianth parts is variable, ranging from three to nine, even within a single species, e.g. Desmos chinensis (Fig. 3C), Cananga odorata (Fig. 4L, M). Non-trimerous (tetramerous) flowers (with four perianth parts per whorl) occur occasionally in Desmos chinensis (Fig. 3C), Cananga odorata (Fig. 4L, M), Uvaria microcarpa (Fig. 6D, E) and Artabotrys hexapetalus (Fig. 7B), but tend to be more common in C. odorata var. fruticosa (Fig. 5F, G).

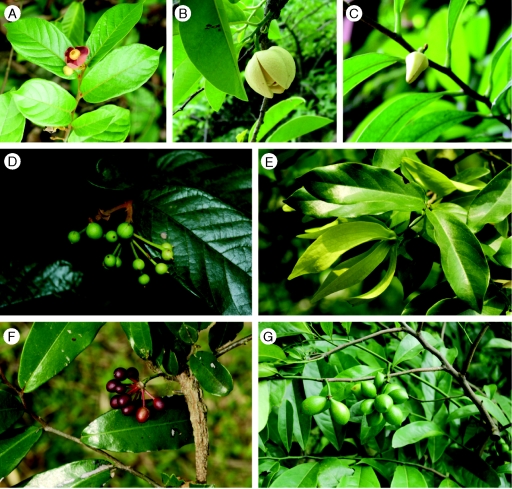

Fig. 1.

Flowers at anthesis (A–C, E) and fruits (D, F, G): (A) Uvaria microcarpa; (B) Annona glabra; (C) Alphonsea monogyna; (D) Uvaria microcarpa; (E) Artabotrys hexapetalus; (F) Polyathia suberosa; (G) Artabotrys hexapetalus.

Fig. 2.

Flowers at anthesis: (A) Cananga odorata var. fruticosa; (B) Annona squamosa; (C) Mitrephora maingayi; (D) Desmos chinensis; (E) Mezzettiopsis creaghii; (F) Miliusa sinensis (floral buds).

Fig. 3.

Floral development of Desmos chinensis: (A, B) initiation of the middle (asterisks in A) and inner perianth whorl (asterisks in B); (C) four perianth members in the inner whorl make the floral apex quadrangular – note two perianth members in double position (asterisks); (D) distal view of the perianth, hairs on the back of the second whorl members (asterisks); (E) initiation of first stamen primordia (stars) in three pairs on both sides of the inner perianth member; (F) further stamens initiated along the sides of the floral apex (arrowheads), and hairs appear on the back of the second whorl members (asterisks); (G) floral apex is more or less hexagonal, stamens appearing centripetally in rapid succession; (H) young carpels, showing no difference with the stamen primordia; (I) nearly mature bud, with incomplete parastichies and orthostichies; (J) distal view of the floral bud before anthesis. Abbreviations: f, floral apex; c, carpel; ip, inner perianth whorl; mp, middle perianth whorl. Scale bars: (A, B, D) = 200 µm; (C, E–I) = 500 µm; (J) = 1 mm.

Fig. 4.

Floral development of Polyalthia suberosa (A–K) and Cananga odorata (L–O): (A) the middle whorl perianth organs arise at the tips of the three angles, with one of them initiated slightly earlier (asterisk); (B) middle and inner perianth whorl, one middle perianth member advanced with hairy crest along the back (asterisk); (C) flower bud with variably sized tepals – note the bilobed larger inner tepal (asterisks); (D) the androecium firstly develops as three pairs (stars) on both sides of the inner perianth member; (E, F) after the formation of the first three stamen pairs, several additional stamens are initiated (arrowheads); (G) quadrangular floral apex with four inner perianth members (asterisks, two removed); (H) further stamens are initiated on a hexagonal floral apex – note the outer stamen pairs (stars); (I) initiation of carpels; (J) nearly mature bud, with sets of antidromous parastichies of the same steepness; (K) distal view of the hairy gynoecium in a mature flower bud; (L) unusual quadrangular flower with more than three inner perianth members; (M) comparable floral apex with four perianth members in the middle whorl (asterisks) and up to six members in the inner perianth whorl; (N) centripetal initiation of several stamen whorls (outer pairs shown by stars) – the androecium is hexagonal with the sides in front of the inner perianth members slightly longer than those of the middle perianth whorl; (O) apical view of flower with ten-carpellate gynoecium. Abbreviations: f, floral apex; c, carpel; s, stamen; ip, inner perianth whorl; mp, middle perianth whorl. Scale bars: (A–C, E–I, M) = 200 µm; (D, J–L, N, O) = 500 µm.

Fig. 6.

Floral development of Uvaria microcarpa (A–N) and Fissistigma retusum (O): (A) the remaining floral apex is more or less triangular, and the middle whorl perianth organs arise at the tips of the three angles and are followed by those of the inner perianth whorl (asterisks); (B) flower bud from above showing one intermediate tepal slightly larger than the others (asterisk); (C) flower bud with unequal size of intermediate tepals – one perianth member is much larger than the other two and lobed (asterisk); (D, E) unidirectional initiation of the second and third perianth whorls; (F) flower with lobed middle perianth parts; (G) one middle perianth member is much larger and covers the remaining tepals (asterisk); (H) first-initiated stamens (stars) arise as three pairs on both sides of the inner perianth member; (I) after the formation of the first three stamen pairs (stars), several additional stamens are initiated (arrowheads); (J) the first three stamen pairs (stars) are more prominent; (K) quadrangular bud showing the larger size of the first-initiated stamens (stars); (L) numerous stamens are initiated rapidly and centripetally; (M) outer whorl stamens (staminodes) are flattened; (N) nearly mature bud, deep ventral groove extending to the tip of each carpel; (O) mature bud, with hairs between the carpels and stamens. Abbreviations: f, floral apex; s, stamen; ip, inner perianth whorl; mp, middle perianth whorl. Scale bars: (A, D, E) = 200 µm; (B, C, F–M) = 500 µm; (N, O) = 1 mm.

Fig. 7.

Floral development of Artabotrys hexapetalus (A–H) and Pseuduvaria indochinensis (I–L): (A) sequential initiation of the three outer perianth members; the floral apex becomes triangular; (B) quadrangular floral apex with nine perianth members formed in the intermediate and inner whorls (asterisks); (C) initiation of the middle and inner perianth whorl (inner perianth asterisks); (D) flower bud with five inner tepals, four in double position (asterisks); (E) the first three stamen pairs are formed on both sides of the inner perianth member (stars), and several additional stamens begin to develop (arrowheads); (F) further stamens are initiated centripetally; (G) carpels initated without clear sequence; (H) nearly mature bud, the first three stamen pairs are slightly larger than others (stars); (I) distal view of the perianth, hair on the back of the second whorl perianth member (asterisk); (J) centripetal initiation of stamens – note three outer stamen pairs (stars); (K) numerous stamens with incomplete orthostichies; (L) mature bud, showing compact stamen arrangement – note the three upper stamens replacing carpel positions. Abbreviations: f, floral apex; c, carpel; s, stamen; ip, inner perianth whorl; mp, middle perianth whorl. Scale bars: (A–F, I–K) = 200 µm; (G, H, L) = 500 µm.

Fig. 5.

Floral development of Cananga odorata (A, B) and C. odorata var. fruticosa (C–N): (A) the depression in each carpel becomes a deep groove during development; (B) apical view of a nearly mature floral bud, with tightly packed carpels and convolute stigma lobes; (C) apical view of floral apex before perianth initiation; (D) the remaining floral apex is triangular, and the middle whorl perianth primordia arise at the tips of the three angles (asterisks); (E) the inner perianth whorl (asterisks) alternating with the middle one; (F, G) one or two members of the inner perianth primordia are doubled (asterisks), and a hairy crest develops along the back of the middle perianth members; (H, I) the androecium is initiated as three stamen pairs on both sides of the inner perianth member (stars); (J) the first formed stamens are larger in size (stars, especially opposite the second perianth whorl) than those of the following stamen primordia; (K) further stamens are initiated centripetally in a relatively rapid succession; (L, M) carpels initiated with little difference in stamens at this stage; (N) unordered arrangement of carpels – note the larger size of outer stamens (stars). Abbreviations: f, floral apex; c, carpel; s, stamen; ip, inner perianth whorl. Scale bars: (A, B) = 1 mm; (C–F, H–J) = 200 µm; (G, K, L–N) = 500 µm.

Most species examined have a large number of stamens, firmly packed together, with the carpel tips standing out in the centre (Figs 3J, 4K, 5A, 6N and 8J). In some genera the number of stamens is intermediate (Fig. 9H, M, N), or limited to six stamens arranged in a cycle (Fig. 10K, L). The number of carpels is highly variable ranging from a single carpel (Fig. 9G, H) to few (less than ten; Fig. 6O), to many (over 100; Fig. 8J).

Fig. 9.

Floral development of Alphonsea monogyna (A–H), Miliusa sinensis (I–M) and M. chunii (N): (A) sequential initiation of outer perianth members – the first is indicated with an asterisk; (B) the three outer perianth parts initiated surrounding the triangular floral apex; (C, D) formation of the middle and inner perianth whorl (inner perianth organs with asterisks); (E) stamens are formed centripetally; (F) initiation of a single carpel; (G) a depression is formed on the ventral side of the carpel; (H) mature bud – note the hairs between the carpel and stamens; (I) floral bud with middle and inner perianth whorl initiated, showing hairy crest developing along the back of the middle perianth organs; (J, K) carpels formed with little difference from stamens – note the arrangement of stamens and carpels in incomplete orthostichies; (L) a deep groove is formed on the ventral surface of each carpel; (M) nearly mature bud showing stamens with bulging thecae and papillate connective; (N) mature bud, carpels with elongating styles. Abbreviations: f, floral apex; c, carpel; s, stamen; ip, inner perianth whorl; mp, middle perianth whorl. Scale bars: (A–F, I–K) = 200 µm; (G, H, L, M) = 500 µm; (N) = 1 mm.

Fig. 10.

Floral development of Mitrephora thorelii (A–F) and Mezzettiopsis creaghii (G–L): (A) the middle whorl perianth organs formed at the three angles of the remaining floral apex; (B) one member of the inner perianth whorl is slightly larger (asterisk) than the other two, first stamens (stars) formed on both sides of the inner perianth member; (C) the remaining floral apex (including the androecium) is hexagonal with the sides in front of the inner perianth members slightly longer than those of the middle perianth whorl; (D) formation of stamens and carpels; (E) nearly mature bud, with little differentiation between style and stigma; (F) mature bud with compact arrangement of stamens and carpels; (G) six stamens are formed (stars in consecutive figures); (H, I) successive formation of carpels; (J) a deep groove develops on the ventral surface of each carpel during development – note the unoccupied remaining floral apex; (K) nearly mature bud, showing the stigmas; (L) mature bud, showing a compact gynoecium surrounded by six stamens with bulging thecae. Abbreviations: f, floral apex; c, carpel; s, stamen; ip, inner perianth whorl; mp, middle perianth whorl. Scale bars: (A–D, G–J) = 200 µm; (E) = 500 µm; (F, K, L) = 1 mm.

Fig. 8.

Floral development of Annona squamosa (A–H) and A. glabra (I, J): (A) the three outer perianth members initiated; the remaining floral apex is triangular (bract removed); (B) second whorl of perianth organs formed at the three angles of the floral apex (asterisks); (C) slightly later stage – note the narrow bulges corresponding to the third perianth whorl (asterisks); (D) later stage development of the inner perianth whorl, with three primordia arrested in growth (asterisks); (E) stage before stamen formation – the floral apex becomes more or less round – and with perianth removed undeveloped perianth primordia can be distinguished (asterisks); (F) early stage of stamen initiation; (G) initiation of further stamens in a rapid centripetal succession; (H) initiation of carpels showing little difference from stamen primordia; (I, J) numerous stamens and carpels formed in centripetal succession with orthostichies in the upper whorls. Abbreviations: f, floral apex; b, bract; ip, inner perianth whorl. Scale bars: (A–E) = 200 µm; (F–I) = 500 µm; (J) = 1 mm.

In general the flowers of the family are bisexual, but a number of genera are dioecious with unisexual flowers (e.g. Pseuduvaria indochinensis).

Floral ontogeny

Perianth

The floral apex is circular (Fig. 5C) at initiation in all species examined but becomes triangular after the first three perianth parts are formed. The outer perianth parts are wide and dorsiventral, initiated successively, with one of them arising slightly earlier than the other two and opposite the bract on the other side of the bud (Figs 5D, 7A, 8A and 9A, B). The primordia of the middle perianth whorl are circular to semi-circular, initiated successively at the tips of the three angles formed by the triangular floral apex in alternation with the outer whorl. Initiation is rapid but similar to the outer whorl and one of the perianth parts differs slightly from the other two in time of initiation, mostly being slightly retarded (Figs 3A, 4A, B, 5D, E, 6A, 8B, C, 9C and 10A). In other buds, size differences are more pronounced and, in some cases, one member of the intermediate whorl is much smaller or missing, leading to an unidirectional initiation (Fig. 6D, E). In some species, one of the perianth members is much larger than the other two, e.g. Uvaria microcarpa and Polyalthia suberosa (Figs 4C and 6B, C, F).

The initiation of the inner perianth whorl is similar to the middle one. The organs arise more or less simultaneously, in a position alternating with the middle one. The divergence angles in these two whorls are approx. 100–130°. The inner whorl grows much slower than the middle whorl, judged from the considerable difference in size of the young organs (Figs 3B, 6H, 7C, 9D and 10B). In Annona squamosa the perianth members of the inner whorl are much smaller and are arrested in growth (Fig. 8D, E). One is occasionally missing. Usually, the perianth consists of three alternating trimerous whorls. In some cases, however, flowers are tetramerous with four members in each whorl (Figs 3C, 4G and 5I). The members of the outer and inner whorls are diagonally placed relative to the bract. In several flowers the members of the inner whorl are in double position and this arrangement occurs in trimerous as well as tetramerous flowers (Figs 3C, 5F, G and 7B, D). In Cananga odorata (Fig. 4M), four members were observed in the middle whorl and up to six members in the inner perianth whorl. The paired primordia have a similar or a different size. The members of either the intermediate or the inner whorl of Uvaria showed a tendency for lobing (Fig. 6C–G). A hairy crest develops along the back of each perianth member (Figs 3D, F, 4C, M, 5G, 7I and 9I). After the completion of the perianth initiation, the remaining floral apex is more or less regularly hexagonal (Figs 3G and 4H; or tetragonal in tetramerous flowers) in outline in most of the species examined, or the sides in front of the inner perianth members are slightly longer than those of the middle perianth whorl (Figs 4N, 6J, 7E and 10C). Due to the tetramerous perianth arrangement in the inner whorl, the floral apex becomes quadrangular in Desmos chinensis (Fig. 3C), Polyalthia suberosa (Fig. 4G) and Cananga odorata (Fig. 4L).

Androecium

The androecial development starts simultaneously with six primordia, situated on both sides of the three inner perianth members and forming a whorl (Figs 3E, 4D, 5H, I, 6H and 7E). In Mezzetiopsis stamen initiation is terminated with these six stamens (Fig. 10G), but in other genera the number of stamens is much higher. The six stamens are generally larger in size than the following stamens, which are successively initiated along the sides of the hexagonal floral apex (Figs 5J, K, 6I–K and 7F, J), or they do not differ much in size (Figs 4E–H, 8F, G and 10D). Further stamens originate on the floral apex centripetally in a relatively rapid succession. In flowers with a relatively low stamen number (Fig. 9E, F, J), stamen initiation runs in a regular sequence of hexamerous and trimerous whorls, while in flowers with much higher stamen number initiation appears in flushes with little indication of a sequence pattern (Figs 3G, H, 4I, 5K, L, 6L, 7G, 8H and 10D). In some species it was possible to detect incomplete parastichies at least in the upper whorls (Figs 3H, I, 4I, J, 7K, 8I, J and 10E, F). The outer stamens appear to be more regularly arranged in whorls or in linear series, with more stamens opposite the median perianth parts, while the arrangement is less clear higher up the apex. In the staminate flowers of Pseuduvaria indochinensis there is no trace of a gynoecium and stamens cover the whole floral apex in regular trimerous whorls (Fig. 7K–L).

Stamens are narrowly oblong to oblanceolate, with part of the thecae free in Miliusa and Mezzetiopsis. Anthers are extrorse in Alphonsea (Fig. 9H), Miliusa (Fig. 9M, N), Mezzettiopsis (Fig. 10K, L) and Pseuduvaria (Fig. 7L), with extended papillate connective except in Pseuduvaria. The connective is spinescent in Cananga odorata (Fig. 5A). Flattened stamens were found in Uvaria microcarpa (Fig. 6M, N), and tongue-like stamens appear in most of the species examined.

Gynoecium

The number of carpels ranges from a single terminal carpel (Alphonsea monogyna) to several hundreds (e.g. Annona). Initiation of carpels could not be distinguished from stamens in early stages (Figs 3H, 4I, 5L, M, 6L, 7G, 8H, 9J and 10E). The first carpels are differentiated exactly in alternation with the latest stamen primordia, and remain free from each other. In Mezzettiopsis, carpel initiation follows the six stamens in the same sequence as would be expected for stamens (Fig. 10H, I). In Miliusa, carpels continue the sequence of initiation after several series of stamens (Fig. 9J, K). Towards the top of the floral apex, initiation of carpels appears chaotic or at least helical and not whorled, as space for initiation becomes limited. The young carpels initially have a circular base but as they increase in size a slight depression appears at the ventral face. The depression becomes a deep groove during further carpel development and the carpels become horseshoe-shaped (plicate; Figs 3I, 4O, 5A, N, 6N, 8I, 9L and 10I, J). In adult flowers the limits between style and stigma are difficult to make. A long slit is generally observed in all species except Cananga odorata where the margins of the style become convolute (Fig. 5B). Carpels are squeezed in the space between the compact stamens and cover the whole apex (Figs 3J, 5B, 7H and 10E, F). Hairs develop between carpels and stamens (Figs 4K, 6K and 9G, H) or carpels become strongly papillate (Fig. 10L).

DISCUSSION

In recent phylogenetic analyses, either on molecular sequences or morphological characters or combined together, four clades were recognized in Annonaceae (Sauquet et al., 2003; Doyle et al., 2004). Anaxagorea is the sister group of the remaining taxa of Annonaceae. The rest of the family was consistently distributed into an ambavioid clade (Ambavia + Cananga), a MPM clade (here represented by Polyalthia), and an inaperturate clade (all remaining genera) (Doyle and Le Thomas, 1996; van Zuilen, 1996; Doyle and Endress, 2000; Doyle et al., 2000; Sauquet et al., 2003; Richardson et al., 2004). Anaxagorea is an ancient genus, basically of South American distribution.

From the phylogenetic analysis and trends in character evolution, it is certain that the species investigated do not form a basal group in Annonaceae, and that they have a mixture of derived features, e.g. reduction or loss of the inner perianth, stamens less than ten and without inner staminodes, or excessively high, presence of unisexual flowers, carpels occasionally reduced to one or two and with capitate or elongated stigmas, or much higher. However, these derived features are not concentrated in a specific species or genus. Instead, they are distributed in each clade and evolved independently.

In previous studies, the members of the outer perianth whorl were usually considered as sepals, since they are smaller and shorter than the members of the middle and inner perianth whorls (e.g. Ronse De Craene and Smets, 1990; van Heusden, 1992; Doyle and Le Thomas, 1996; Leins and Erbar, 1996). Typical petals are generally coloured, have a single vascular trace, and are retarded in development as compared with sepals and stamens, and are ephemeral (Endress, 2001; Ronse De Craene, 2007). Structurally and phylogenetically, all perianth parts are similar in Annonaceae; they all arise successively with the outermost perianth parts larger than those of the inner two whorls, and with little difference between the inner two whorls in shape or size. However, the inner perianth usually behaves differently from the outer perianth in Annonaceae. While the three outer members are usually larger in younger buds, they become insignificant at anthesis. In Pseuduvaria indochinensis, the three inner perianth members remain closed over the flower centre. In Annona there is a strong tendency for the inner petals to become lost, although they are usually initiated and are much smaller (e.g. A. cherimola: Leins and Erbar, 1996) or they are initiated but are soon arrested in their development and invisible at maturity (this study). The inner petals may be totally lacking (Fries, 1959). In Enantia the middle whorl is missing (Fries, 1959). Most Anaxogorea have inner petals, except A. borneensis and A. javanica where they were independently lost (Scharaschkin and Doyle, 2006).

Stamen morphology is one of the more informative characters for the family. Inner staminodes were reported in Annonaceae (e.g. Anaxagorea and Xylopia) and most Magnoliales except Magnoliaceae and Myristicaceae (Doyle and Le Thomas, 1996; Endress and Doyle, 2009). In the present study, there is no differentiation of inner and outer stamens in most species; all stamens seem to have a similar size and shape. However, in Uvaria microcarpa and Canaga odorata var. fruticosa, the outer stamens are broader and larger than the inner ones and laminar, considered to be staminodial (Doyle and Le Thomas, 1996). A tendency for outer stamen reduction was clearly shown in Monanthotaxis whytei with a reduction of outer staminodes into inconspicuous bumps (Ronse De Craene and Smets, 1990). In this study, the outer stamens are larger, laminar and, probably, staminodial in Uvaria. Inner staminodes of a laminar type were considered as ancestral and are present in the basal Anaxagorea (Doyle and Le Thomas, 1996; Scharaschkin and Doyle, 2006).

An average number of carpels (usually more than ten) has been interpreted as the basic state for the family (Doyle and Le Thomas, 1996). In the present study, only A. monogyna has one to two carpels, while other genera have over ten carpels, in Annona and Polyalthia suberosa even over 100. The stigmas are basically sessile in the family; capitate stigmas were observed in Cananga odorata and C. odorata var. fruticosa, while more or less elongated styles could be detected in Miliusa chunii and M. sinensis. An evolutionary trend was considered from sessile to capitate to elongate stigmas (Doyle and Le Thomas, 1996).

Changes in merism and doubling of organ position in the perianth

Although trimerous flowers are one of the unifying characteristics of the monocotyledons, trimery appeared in angiosperms as an ancient trait before the differentiation of the monocotyledons (Dahlgren, 1983; Ronse De Craene and Smets, 1994; Ronse De Craene et al., 2003; Endress and Doyle, 2009). Two different forms of trimery were proposed by Kubitzki (1987): one originating from helical phyllotaxis, and another reached stepwise by a progressive reduction of merism. The former pattern is characteristic of Annonaceae. The perianth parts are initiated in a rapid sequence in each whorl, with one of them arising a little earlier than the other two (Figs 3A, B, 4A, B, 5D, E, 6A, B, 7A, C, 8B, C, 9A–D and 10A, B; cf. Leins and Erbar, 1996). The plastochrons are very short within a whorl, while they are longer between the last organ of a whorl and the first organ of the subsequent whorl, since the primodium size is different between two successive whorls. In this sense, trimery seems to have occurred first in the perianth in Annonaceae.

While most Annonaceae have trimerous flowers with strictly alternating whorls, several species were found to be occasionally variable in number of parts. Two independent processes seem to be creating this variation, namely a change in merism and increases by doubling of organ positions. Both phenomena are independent but may operate in unison. Fluctuations in merism were found in Artabotrys, Cananga, Desmos, Polyalthia and Uvaria, and flowers were either trimerous or tetramerous (Figs 3C, 4L, M, 5A, N, 6K and 7B). In tetramerous flowers, initiation of perianth parts was often unidirectional or irregular. Variability in perianth numbers has also been reported by Fries (1959) and Deroin (1989) for other genera (e.g. Ambavia and Feneriva). Tetrameranthus was reported to have four sepals and eight petals in two whorls (Kessler, 1993).

The change in merism from trimery to tetramery is comparable to the variation observed in Nymphaeaceae (Endress, 2001; e.g. Victoria), Winteraceae (Doust, 2000) or Monimiaceae (Staedler and Endress, 2009). The causes for this change of merism in Annonaceae are unclear, while they seem to affect a limited number of species. Besides a change in merism, inner petals tend to have a double position in many cases (e.g. Artabotrys, Desmos, Cananga and Polyalthia; Figs 3C, 4C, 5F, G and 7B, D), or petals tend to be multilobed (e.g. Uvaria; Fig. 6C, F). When inner perianth parts are doubled in position, they tend to be much smaller relative to the floral apex and resemble stamen primordia to a certain extent. This was also reported by Endress (1994) for Artabotrys hexapetalus. Deroin (1989) described the variation of the perianth of Ambavia gerrardii as evidence for an affinity with Polyalthia, which expresses a similar variation in number of inner perianth parts. However, one should be careful in assigning all higher perianth numbers as an increase, as they may also result from homeosis of stamens (see below; Ronse De Craene, 2003). Double positions of perianth organs are not rare in basal angiosperms. They occur on a frequent basis in Monimiaceae and Atherospermataceae (e.g. Endress, 1994; Staedler and Endress, 2009), Nymphaeaceae and Cabombaceae (Endress, 2001) and in Winteraceae (Endress, 1994; Doust, 2000). While in those families the paired arrangement appears to be the result of spatial shifts, linked with the insertion of smaller organs in the phyllotactic sequence, doubling of perianth parts is haphazard and obviously the result of a division in Annonaceae (Figs 4C and 6C, F), contrary to the androecium (see below). A comparable pattern of increase of the inner series of petals was observed in Salicaceae by Bernhard and Endress (1999) (e.g. Caloncoba and Camptostylus).

Variation of initiation patterns

Phyllotaxis is extremely fluctuating in basal angiosperms, with easy switches between spiral and whorled phyllotaxis. Reconstructions on phylogenetic trees show a general correlation between perianth and stamen phyllotaxis, except for Magnoliales (Zanis et al., 2003; Endress and Doyle, 2009). Endress and Doyle (2009) reconstruct a whorled perianth as ancestral for Magnoliales (and basal angiosperms, although the ancestral condition for angiosperms is equivocal). For Annonaceae, perianth and androecium are reconstructed as whorled. This would imply that a switch to a spiral perianth as in some Magnoliaceae or at the base of Laurales is a reversal. However, this seems to be contradicted for the androecium, where a spiral condition is seen as a retention from the first angiosperms.

Developmental patterns of floral organs are highly variable in Annonaceae, ranging from helical, unidirectional, to simultaneous, or a mixture of different patterns. The perianth is initiated in a rapid helical sequence in most cases. In helical phyllotaxis, the divergence angle usually approaches the ‘golden’ limiting angle (137·5°). In the present study, the perianth members were arranged in whorls on the same radius and alternated with those of the preceding whorl, with a divergence angle somewhat intermediate between 100 and 130°. The first perianth member is initiated on the opposite side of the bract and is followed by two other perianth organs. The initiation of the middle and inner perianth is either helical, nearly simultaneous, or occasionally unidirectional, or without clear order (Artabotrys; Fig. 7B). In Uvaria initiation of the perianth was occasionally unidirectional and this was linked to a reduction or loss of one of the intermediate perianth parts (Fig. 6D, E, G).

The number of stamens is variable, ranging from few to numerous, with stamens often inserted in multiples of three and six (e.g. Ronse De Craene and Smets, 1990; Leins and Erbar, 1996) or with a reduction to six stamens in one whorl [e.g. Mezzetiopsis creaghii (present study) and Bocagea and Orophea (Baillon, 1867)] or three opposite the outer perianth [Orophea (Fries, 1959; van Heusden, 1992)]. The first six stamens are always arranged in pairs as observed in this study (Figs 3E, F, 4D, 5H, 6H, 7E, 9E and 10B, G), but also reported previously (Ronse De Craene and Smets, 1990; Leins and Erbar, 1996). The fate of further stamens is highly variable and depends on the size of stamen primordia relative to the size of the floral apex. In flowers with relatively few stamens, whorls succeed in an alternation of six or three stamens (Figs 7F, J, K and 9E, F, J, K). With higher stamen numbers, further stamens tend to arise in girdles of several units or in flushes (Figs 3G, 4E, F, 5J, 6J and 8F). With many, smaller stamens, their appearance is linked with pressures of the perianth parts, and the first stamens arise in areas alternating with the inner perianth (Figs 3F and 5J).

A paired stamen arrangement was considered as derived from the early stages of the initiation of a helical androecium (Erbar, 1988), or was seen as a basic step in the compression of the androecial helix into whorls (Ronse De Craene and Smets, 1990, 1996). Endress (1987, 1994) regarded the paired arrangement of stamens as a doubling of position, caused by the smaller base of stamens compared with the perianth parts. Cases with double positions are widespread and include stamens or perianth parts. Several trimerous or dimerous magnoliid flowers (e.g. Cabombaceae, Aristolochiaceae, Monimiaceae, Winteraceae and Magnoliaceae), as well as basal monocots (e.g. Alismataceae and Butomaceae) and Ranunculales (e.g. Ranunculaceae and Papaveraceae) have stamens arranged as pairs. Staedler and Endress (2009) described this pattern of development as ‘complex whorled’. In Laurales, doubling affects inner perianth parts, staminodes and stamens and leads to changes in merism. A double position is always associated with a decrease in organ size and with a whorled phyllotaxis. A crucial question is whether it is a replacement of a single organ by two or more organs, or the consequence of an increase in size of the perianth, forcing consecutive organs to become arranged as pairs. Erbar and Leins (1994) interpreted the transition of a helical perianth to a trimerous perianth in Magnoliaceae as a break-up of a helical initiation in an alternation of short and long plastochrons and the arrangement of perianth parts in three trimerous whorls, although the example of a spiral flower they used (Magnolia stellata) is not a basal species. A similar argument was used for Annonaceae (Leins and Erbar, 1996). As a result of the break-up of the spiral and a transition to the much smaller size of stamen primordia, stamen initiation becomes disrupted and a paired arrangement results from this. The arguments of Erbar and Leins tend to be contradicted by phylogenetic studies implying that a whorled perianth phyllotaxis is plesiomorphic in Magnoliales (Endress and Doyle, 2009). Also in Monimiaceae and close relatives, there is no evidence for a transition of a spiral flower into a whorled flower, although the basal family of Laurales, Calycanthaceae, is spiral (Staedler and Endress, 2009). However, several reversals from whorled to spiral phyllotaxis cannot be excluded. The model presented by Erbar and Leins can function as a plausible explanation for the existence of paired organs and to describe patterns of androecial evolution. The low number of extant basal angiosperms and the limited data from fossils need to be taken into account as limitations to the interpretations of character reconstructions. As in Magnoliaceae with a trimerous perianth and a paired arrangement of the outer stamens (see Erbar and Leins, 1994), a whorled arrangement starts from the periphery in Annonaceae with simultaneously initiated paired stamens and moves centripetally. Arrangement of stamens in Annonaceae can be strictly whorled, building orthostichies. With a moderate number, stamens are arranged in whorls of six and three, and this arrangement is usually continued in the gynoecium (e.g. Alphonsea, M. creaghii, Monanthotaxis and Pseuduvaria). With higher stamen numbers external stamens may be arranged in regular whorls, which break down higher up on the receptacle, leading to incomplete parastichies and orthostichies (e.g. Artabotrys and Polyalthia). Parastichies in the androecium were also reported by Erbar and Leins (1994) and Leins and Erbar (1996).

An increase in the number of stamens by a multiplication of much smaller initials and an increase in the size of the floral apex lead to an initiation of flushes of stamens without clear order of initiation. With an incomplete phylogeny of Annonaceae it is not possible to know the plesiomorphic stamen number in the family, although most sister families of Magnoliales have many stamens in a spiral phyllotaxis (except Myristicaceae having both whorled and spiral androecia). Scharaschkin and Doyle (2006) considered that species of Anaxagorea with more than 100 stamens have undergone an increase in stamen number. The very high number of stamens is inversely correlated with their size and could be described as derived from a moderate number of stamens (Leins and Erbar, 1996). The large number of smaller primordia makes it very difficult to observe the sequence of initiation of the androecium and gynoecium, which is often referred to as irregular.

Carpel initiation is usually whorled, helical or irregular by space constrictions at the top of the apex. Initiation patterns can be strongly altered by changes in merism and doubling of perianth parts (see above). Carpel initiation tends to continue the sequence of the stamens, especially in flowers with a moderate number of stamens. However, as space becomes restricted higher up on the apex, carpels tend to be arranged in an unordered or helical phyllotaxis with some incomplete parastichies in the upper part of the gynoecium (Figs 3H, 4I, O, 6L, 8H and 10D; Endress, 1987; Leins and Erbar, 1996). In some species such as Monanthotaxis whytei the carpels arise in three alternating whorls of nine (Ronse De Craene and Smets, 1990). In the present study, gynoecium development was comparable to that of stamens, with small initials formed in a rapid sequence, alternating with the last-formed stamens. In A. hexapetalus and P. suberosa, the carpels are more or less loosely arranged (Figs 4I–K and 7G, H), not as compressed as in other species of Annonaceae (e.g. U. microcarpa) or Magnoliaceae (Xu and Rudall, 2006). Doyle and Le Thomas (1996) considered ten carpels as the basic state for the family. As with stamens, carpel numbers can become reduced to a single carpel as has been reported for six genera in Annonaceae, or carpel numbers fluctuate highly within a genus (Fig. 9G and H; Kessler, 1993; Leins and Erbar, 1996).

The transition between different organ categories is rarely well marked, especially between androecium and gynoecium. There is apparently no constraint for stamens to become replaced by carpels and vice versa, as is visible in the unisexual flowers of Pseuduvaria, or in Miliusa or Mezzetiopsis with a low stamen number (Figs 7K, L, 9K–N and 10I–L). In Mezzetiopsis carpels occupy the expected position of stamens in other species of Annonaceae with an intermediate number of stamens. Stamen and carpel numbers tend to fluctuate, depending on the size of the floral apex. In flowers of basal angiosperms with numerous organs, helical phyllotaxis appears to provide a more efficient spacing of organs than whorled phyllotaxis (Endress and Doyle, 2007). Perianth primordia are occasionally similar in shape to stamen primordia, especially where the inner perianth parts are reduced or variable (e.g. Annona and Cananga). In some genera the six outer stamens may become homeotically replaced by extra perianth parts, as in Fenerivia heteropetala or Toussaintia hallei (Deroin, 2000, 2007).

Conclusions

Flowers of Annonaceae tend to be extremely variable, with highly fluctuating stamen and carpel numbers. In contrast, the perianth is generally trimerous and differentiated in three alternating whorls. Merism tends to be variable in the family with easy transitions between trimery and tetramery, although trimerous flowers are probably plesiomorphic. The inner perianth can be doubled by (un)equal division of organs and this appears to be independent of changes in merism. Outer stamens are universally arranged as three pairs. The double stamen positions are the consequence of the transition between large perianth parts and much smaller stamens and not a result of a division, contrary to the inner perianth. We believe that the androecium has evolved in two opposite ways from a moderate number of stamens, either becoming oligomerous by loss of whorls and sterilization of outer stamens, or with a secondary increase, correlated with their smaller size at initiation. Limits between stamens and carpels are unclear with easy transitions of one organ type into another in some genera, or the complete replacement of carpels by stamens in unisexual flowers. Derived features, such as a variable merism, absence of the inner perianth and inner staminodes, fixed numbers of stamens and carpels, and capitate or elongate styles are distributed in different clades and evolved independently.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Frieda Christie for her technical assistance with the scanning electron microscope at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, UK, and also Dongqin Chen, Xiaobing Yang and Xinyu Yang for collecting samples. This work was financially supported by the National Sciences Foundation of China (grant number 30770140) and the National Sciences Foundation of Guangdong province, China (grant number 5006764). We acknowledge the following individuals for their photographs: Mr Yushi Ye, Figs 1A, D, E and 2A–C, F; Mr Keming Yang, Fig. 2D; and Miss Xingyu Yang, Figs 1B, C and 2E.

LITERATURE CITED

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 2009;161:105–121. [Google Scholar]

- Baillon H. Mémoire sur la famille des Annonacées. Adansonia. 1867;8 162–184, 295–344. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard A, Endress PK. Androecial development and systematics in Flacourtiaceae s.l. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 1999;215:141–155. [Google Scholar]

- Cronquist A. An integrated system of classification of flowering plants. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren R. General aspects of angiosperm evolution and macrosystematics. Nordic Journal of Botany. 1983;3:119–149. [Google Scholar]

- Deroin T. Definition and phylogenetic significance of floral cortical systems: the case of Annonaceae. Comptes Rendus de la Academie des Sciences Serie III. 1989;308:71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Deroin T. Floral anatomy of Toussaintia hallei Le Thomas, a case of convergence of Annonaceae with Magnoliaceae. In: Liu YH, Fan HM, Chen ZY, Wu QG, Zeng QW., editors. Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Family Magnoliaceae. Beijing: Science Press; 2000. pp. 168–176. [Google Scholar]

- Deroin T. Floral vascular pattern of the endemic Malagasy genus Fenerivia Diels (Annonaceae) Adansonia, Serie 3. 2007;29:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Doust AN. Comparative floral ontogeny in Winteraceae. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 2000;87:366–379. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JA, Endress PK. Morphological phylogenetic analysis of basal angiosperms: comparison and combination with molecular data. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2000;161(Suppl.):S121–S153. doi: 10.1086/314241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JA, Le Thomas A. Phylogenetic analysis and character evolution in Annonaceae. Bulletin du Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle Paris, Série 4. 1996;18:279–334. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JA, Bygrave P, Le Thomas A. Implications of molecular data for pollen evolution in Annonaceae. In: Harley MM, Morton CM, Blackmore S., editors. Pollen and spores: morphology and biology. Richmond: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; 2000. pp. 259–284. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JA, Sauquet H, Scharaschkin T, Le Thomas A. Phylogeny, molecular and fossil dating, and biogeographic history of Annonaceae and Myristicaceae (Magnoliales) International Journal of Plant Science. 2004;165(Suppl. 4):S55–S67. [Google Scholar]

- Endress PK. Reproductive structures and phylogenetics significance of extant primitive angiosperms. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 1986;152:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Endress PK. Floral phyllotaxis and evolution. Botanische Jahrbücher für Systematik. 1987;108:417–438. [Google Scholar]

- Endress PK. Patterns of floral construction in ontogeny and phylogeny. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 1990;39:153–175. [Google Scholar]

- Endress PK. Diversity and evolutionary biology of tropical flowers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Endress PK. The flowers in extant basal angiosperms and inferences on ancestral flowers. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2001;162:1111–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Endress PK, Doyle JA. Floral phyllotaxis in basal angiosperms: development and evolution. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2007;10:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endress PK, Doyle JA. Reconstructing the ancestral angiosperm flower and its initial specializations. American Journal of Botany. 2009;96:22–66. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0800047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbar C. Early developmental patterns in flowers and their value for systematics. In: Leins P, Tucker SC, Endress PK., editors. Aspects of floral development. Berlin: J. Cramer; 1988. pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Erbar C, Leins P. Flowers in Magnoliidae and the origin of flowers in other subclasses of the angiosperms. I. The relationships between flowers of Magnoliidae and Alismatidae. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 1994;8:193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Fries RE. Annonaceae. In: Melchior H, editor. Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien 2: 17a II. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot; 1959. pp. 1–171. [Google Scholar]

- van Heel WA. A S.E.M. investigation on the development of free carpels. Blumea. 1981;27:499–522. [Google Scholar]

- van Heusden ECH. Flowers of Annonaceae: morphology, classification and evolution. Blumea. 1992;7(Suppl.):S1–S218. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler PJA. Annonaceae. In: Kubitzki K, Rohwer JG, Bittrich V., editors. The families and genera of vascular plants II. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1993. pp. 93–129. [Google Scholar]

- Kubitzki K. Origin and significance of trimerous flowers. Taxon. 1987;36:21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Leins P, Erbar C. Zur Entwicklung der Blüten von Monodora crispata (Annonaceae) Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen. 1980;55:11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Leins P, Erbar C. Das monokarpellate Gynoeceum von Monodora crispata (Annonaceae) Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen. 1982;57:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Leins P, Erbar C. Early floral developmental studies in Annonaceae. In: Morawetz W, Winkler H., editors. Reproductive morphology in Annonaceae. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences; 1996. pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Moncur MW. Floral development of tropical and subtropical fruit and nut species: an atlas of scanning electron micrographs. Melbourne: CSIRO; 1988. Natural Resources Series No. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JE, Chatrou LW, Mols JB, Erkens RHJ, Pirie MD. Historical biogeography of two cosmopolitan families of flowering plants: Annonaceae and Rhamnaceae. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, B, Biological Sciences. 2004;359:1495–1508. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronse De Craene LP. The evolutionary significance of homeosis in flowers: a morphological perspective. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2003;164(Suppl. 5):S225–S235. [Google Scholar]

- Ronse De Craene LP. Are petals sterile stamens or bracts? The origin and evolution of petals in the core eudicots. Annals of Botany. 2007;100:621–630. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronse De Craene LP, Smets EF. The floral development of Popowia whitei (Annonaceae) Nordic Journal of Botany. 1990;10:411–420. [correction in Nordic Journal of Botany11 (1991): 420] [Google Scholar]

- Ronse De Craene LP, Smets EF. Merosity in flowers: definition, origin, and taxonomic significance. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 1994;191:83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ronse De Craene LP, Smets EF. The morphological variation and systematic value of stamen pairs in the Magnoliatae. Feddes Repertorium. 1996;107:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ronse De Craene LP, Soltis PS, Soltis DE. Evolution of floral structures in basal angiosperms. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2003;164(Suppl. 5):S329–S363. [Google Scholar]

- Sauquet H, Doyle JA, Scharaschkin T, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of Magnoliales and Myristicaceae based on multiple data sets: implications for character evolution. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 2003;142:125–186. [Google Scholar]

- Scharaschkin T, Doyle JA. Character evolution in Anaxagorea (Annonaceae) American Journal of Botany. 2006;93:36–54. [Google Scholar]

- Staedler YM, Endress PK. Diversity and lability of floral phyllotaxis in the pluricarpellate families of core Laurales (Gomortegaceae, Atherospermataceae, Siparunaceae, Monimiaceae) International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2009;170:522–550. [Google Scholar]

- Xu FX, Rudall PJ. Comparative floral anatomy and ontogeny in Magnoliaceae. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 2006;258:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zanis MJ, Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Qiu Y-L, Zimmer EA. Phylogenetic analyses and perianth evolution in basal angiosperms. Annals of the Missouri Botanical garden. 2003;90:129–150. [Google Scholar]

- van Zuilen CM. PhD Dissertation, Utrecht University: The Netherlands; 1996. Patterns and affinities in the Duguetia alliance (Annonaceae): molecular and morphological studies. [Google Scholar]