Abstract

Sepsis is the systemic inflammatory response to infection and can result in multiple organ dysfunction syndrome with associated high mortality, morbidity and health costs. Erythropoietin is a well-established treatment for the anaemia of renal failure due to its anti-apoptotic effects on red blood cells and their precursors. The extra-haemopoietic actions of erythropoietin include vasopressor, anti-apoptotic, cytoprotective and immunomodulating actions, all of which could prove beneficial in sepsis. Attenuation of organ dysfunction has been shown in several animal models and its vasopressor effects have been well characterised in laboratory and clinical settings. Clinical trials of erythropoietin in single organ disorders have suggested promising cytoprotective effects, and while no randomised trials have been performed in patients with sepsis, good quality data exist from studies on anaemia in critically ill patients, giving useful information of its pharmacokinetics and potential for harm. An observational cohort study examining the microvascular effects of erythropoietin is underway and the evidence would support further phase II and III clinical trials examining this molecule as an adjunctive treatment in sepsis.

Introduction

Sepsis is the systemic inflammatory response to infection. The clinical syndrome can range from mild constitutional upset to overt septic shock with the failure of multiple organ systems, reflecting the complex pathogenesis of sepsis involving immunological and coagulation pathways [1,2]. The burden from sepsis remains high with worldwide incidence ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 per 1,000 population, a mortality rate at 1 month of 30% from recent randomised trials, and costs of between $11,500 and $22,000 per hospital episode [3,4]. The modulation of single inflammatory pathways (for example, TNFα [5]) and generalised immune suppression with steroids [6,7] has proved unsuccessful in the past, reflecting the complex pathogenesis of sepsis and leading to a reevaluation of the mechanisms that may underlie it. Several laboratory and observational studies have shown that accelerated apoptosis occurs in sepsis and may explain both the organ failure that is a feature of it and secondary infections that can intervene [8-10].

The haematopoietic growth factor erythropoietin (EPO) reduces apoptotic cell death and attenuates inflammation, with cytoprotective effects in both animal and human models of ischaemic injury. EPO also has putative vasopressor actions. A complete summary of the extra-haemopoietic effects of EPO in specific organs is beyond the scope of the present discussion so readers are referred to reviews [11-13]. The present communication seeks to explain the role of apoptosis in sepsis and to summarise the available data on EPO and its extra-haemopoietic effects in sepsis and critical illness.

Cell death in sepsis

Apoptosis is programmed cell death, distinct from necrosis, limiting damage around the penumbra of an injury. This process is important in the homeostasis of the inflammatory response, and delayed neutrophil apoptosis has been implicated in mediating tissue damage in acute respiratory distress syndrome and systemic inflammatory response syndrome [14-16]. That said, accelerated apoptosis has been clearly identified in postmortem studies of septic patients in lymphoreticular tissues and in gut columnar epithelium, conspicuously absent in nonseptic controls [17].

A postulate is that death from sepsis occurs due to overwhelming infection in the face of immuno-suppression due to lymphocyte apoptosis [18]. Indeed, outcome is worse in septic patients with lymphopaenia [19] and in those with evidence of lymphocyte apoptosis [20]. Apotosis of gut epithelium may also lead to bacterial and endotoxin translocation due to a breach in the integrity of the bowel wall. Apoptotic cells per se may have detrimental effects as transfusion of apoptotic splenocytes into septic mice worsens outcome compared with both controls and transfusion of necrotic splenocytes [21].

Modulation of different parts of the apoptosis pathway has been shown to alter outcome in animal models of sepsis: inhibition of Fas/Fas ligand binding, a known promoter of apoptosis, leads to attenuation of liver damage in septic mice [22,23], and overexpression of the anti-apototic B-cell lymphoma protein 2 (Bcl-2) in transgenic mice reduces lymphocyte apoptosis and improves survival in response to sepsis [24]. Caspases are integral in the downstream promotion of cellular apoptosis. The use of caspase inhibitors has been shown to improve survival and reduce lymphocyte apoptosis in one model of sepsis [25] and to reduce apoptosis in acute lung and kidney injury [26].

Both immune-mediated and coagulation pathways are deranged in sepsis, the endothelium being pivotal to these processes [1]. Studies in which endothelial cell lines were infected with bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus have shown consistent evidence of endothelial cell apoptosis [27-31], but in vivo work has failed to show consistent results [32,33] with the easy detachment of cells into the media, making detection difficult.

Although recent data have questioned the balance between apoptosis and necrosis in the outcome from sepsis [34], on balance the data would suggest that attenuation of apoptosis is a fruitful line of investigation to pursue.

Erythropoietin

EPO is a 30.4 kDa glycoprotein hormone and member of the type I cytokine family. Its main function is the regulation of red blood cells through a specific cell surface receptor (EpoR). Stimulation of EpoR reduces apoptosis of red cells via the Janus tyrosine kinase 2 (Jak-2) pathway, increasing their lifespan [35]. After successful clinical trials of EPO in the treatment of anaemia of end-stage renal failure [36,37], its use has been extended to the treatment of anaemia in malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, prematurity and myelodysplasia [13].

The principle site of secretion is the peritubular interstitial fibroblasts of the renal cortex in response to stabilisation and DNA binding of hypoxia-inducible factors [38]. Several inflammatory cytokines increase expression of EpoR and EPO, including insulin-like growth factor, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα, suggesting a role in inflammation [39-41]. Embryologically, EPO-EpoR has a signalling role in angiogenesis and brain development, and EpoR is widely expressed in the brain, retina, heart, kidney, smooth muscle cells, myoblasts and vascular endothelium, suggesting pluripotent effects in normal health and development [13].

Anti-apoptotic effects of erythropoietin

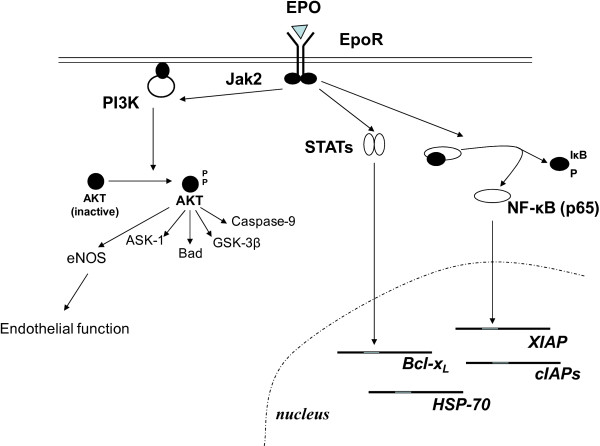

After evidence of a beneficial effect of systemic EPO administration on the course of ischaemic brain injury in mice [42], several animal models of ischaemia/reperfusion have confirmed the cellular, anti-apoptotic effects of EPO in neuronal, renal, endothelial and cardiovascular damage [43,44]. In these models, EPO prevents apoptosis via a number of pathways, dependent on receptor activation by the Jak-2 pathway (see Figure 1). Protein kinase B, an important downstream substance in the Jak-2 pathway, regulates multiple pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic intermediates, including glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), Bcl-2-related death promoter, and the pro-apoptotic forkhead box transcription factor O3a, rendering it unable to activate transcription and nuclear genes involved in apoptosis. EPO increases the expression of several intrinsic inhibitors of apoptosis, including Bcl-2, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein and proto-oncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase 3. In neuronal cells, stabilisation of the transcription factor NF-κB is essential for the anti-apoptotic effects of EPO, although this not been seen in other cell types.

Figure 1.

Anti-apoptotic pathways regulated by erythropoietin. The binding of erythropoietin (EPO) to its dimerised cell surface receptor causes conformational change, leading to activation and autophosphorylation of Janus-tyrosine kinase-2 (Jak2). Jak2 phosphorylates nine tyrosine residues in the intracellular portion of the receptor, which allows interaction with signal transducers and activators of transcription protein (STATs) signalling molecules, and activates phosphoinostitol-3 kinase (PI3K) and hence protein kinase B (AKT). AKT regulates multiple pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic intermediates, including glycogen storage kinase-3β (GSK-3B), B-cell lymphoma protein 2 (Bcl-2)-related death promoter (Bad) and the pro-apoptotic forkhead box transcription factor O3a (FOXO3a), rendering it unable to activate transcription of apoptotic signalling genes. STATs cause transcription of the anti-apoptotic molecules Bcl-2 and proto-oncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase 3 (PIM-3). EPO also activates NF-κB, possibly in a cell-type-specific manner, which alters transcription of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins including inhibitor of apoptosis proteins. ASK-1, apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1; Bcl-xL, B-cell lymphoma extra large; cIAP, baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis protein repeat-containing protein; eNOS, endogenous nitric oxide synthase; EpoR, erythropoietin receptor; HSP70, heat shock protein 70; XIAP, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein.

A carbamylated form of EPO (CEPO), which has low affinity for the classical EpoR and does not cause erythropoiesis, has shown significant anti-apoptotic effects in culture and organ protection in a variety of animal models [45,46]. It is postulated that CEPO signals through a heteroreceptor involving the EpoR and two common β chains of the IL-3 receptor (CD133) [11]. There are clear advantages to an agent that harnesses the beneficial properties of EPO without significant erythropoiesis, and also does not cause platelet and endothelial activation and hence is associated with a less thrombogenic profile [47]. Pyroglutamate-helix B surface peptide (ARA 290, Araim Pharmaceuticals, Ossining, NY, USA) is an erythropoietin analogue modelled on a portion of its 3D structure and although only 11 amino acids long seems to show good neuroprotective and tissue protective effects without eliciting significant haemopoietic or endothelial effects thought to underlie the prothrombotic tendency of EPO [48]. While these molecules are attractive alternatives to EPO with the potential for less side effects these endothelial and pressor effects may actually be beneficial in sepsis syndromes.

Vascular effect of erythropoietin

Septic shock is associated with peripheral vasoplegia [49], requiring catecholamines such as norepinephrine to maintain blood pressure and organ perfusion [50]. The large doses required may cause unwanted side effects, including reduced cardiac output, mesenteric ischaemia and digital gangrene [51]. Vasopressin offset the dose of norepinephrine required to maintain adequate mean arterial pressure (MAP) in a large randomised study [52]; however the side effect profile was similar to norepinephrine suggesting a role for other pressor agents.

Twenty-five to 30% of patients with renal failure treated with EPO develop worsening hypertension [53]. Postulated mechanisms include alteration in blood viscosity, enhanced vascular reactivity and improved vasoconstriction following correction of anaemia [54]. There is accumulating evidence, however, of direct vasopressor effects of EPO, through interaction with EpoR expressed on vascular smooth muscle cells [13]. EPO causes an increase in the cytosolic-free calcium in vascular smooth muscle cells, and augments the effects of angiotensin II [55,56] in addition to upregulating angiotensin II receptor expression [57]. Synergistic effects on cellular calcium levels are seen with endothelin-1 and noradrenaline [56,58].

Activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase leading to increased nitric oxide plays an important role in the pathogenesis of vasodilatory shock [49]. EPO attenuates the effects of interleukin-1β on nitric oxide synthase via direct stimulation of EpoR, providing an alternative pressor effect [59,60]. In addition, EPO increases stability of endogenous nitric oxide synthase via protein kinase B-dependent phosphorylation, and induces increased mRNA expression. In vivo, these changes generate vessel wall tension as shown in isolated rat mesenteric and renal resistance arteries [61]. This appears independent of α- adrenergic stimulation, offering a different pathway for vasoplegia correction. In haemorrhagic shock, the selective α-adrenergic agonist phenylephrine has attenuated effects in intact aortic rings. Pretreatment with EPO reverses this effect with significant increases in the MAP and length of survival of rats [62].

No randomised study has examined the vasopressor effects of EPO in humans; however, in patients with renal failure and on haemodialysis there is a consistent increase in the MAP in response to a single dose of EPO, mediated in part by an increase in the serum endothelin-1 level [63]. In addition, EPO led to a marked increase in the vasoconstricting effects of noradrenaline determined by forearm blood flow in chronic renal-failure patients [64]. In a case series of two patients with vasodilatory shock, administration of 10,000 IU EPO every 4 hours for 24 hours resulted in a brisk and sustained increase in MAP and a rise in the peripheral vascular resistance [65]. EPO has vasoconstrictor effects that could be useful in improving MAP and blood flow to the tissues in severe sepsis and septic shock where vasopressors are required.

Anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective effects of erythropoietin

There are consistent data from the literature confirming anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective effects of EPO in many different animal models of sepsis and inflammation. Both pre and post insult, the administration of EPO attenuates tissue injury. In a rat model of necrotizing pancreatitis, EPO led to a reduction in all features of sepsis-induced acute lung injury, including circulating proinflammatory cytokines, polymorphonuclear cell accumulation and lipid peroxidation, with better maintenance of microvascular cellular integrity [66]. Similar attenuation of inflammation has been shown in response to zymosan (a Toll-like receptor-2 agonist) in mice with reduced local and systemic signs of inflammation and organ dysfunction and lowered levels of TNF and IL-1β compared with control animals [67]. In a rat model of sepsis induced by intraperitoneal lipopolysaccharide, the Toll-like receptor-4 ligand, the effects on lymphocyte and thymic apoptosis as well as serum nitric oxide production were reduced in the group of animals pretreated with EPO [68].

In murine models of sepsis due to caecal ligation and puncture, administration of EPO post insult is associated with a fourfold improvement in the glomerular filtration rate mediated by protective effects on superoxide dismutase [69]. In addition, improvements in perfused capillary density and tissue hypoxia measured by intravital micros copy and changes in nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate fluorescence have been demonstrated, suggesting improved microvascular integrity [70]. Aoshiba and colleagues examined the effects of large doses of EPO in attenuating both increasing lethal doses of lipopolysaccharide and caecal ligation and puncture. There was improved survival in EPO-treated mice, with less apoptosis in the lungs, liver, small intestine, thymus and spleen along with reduced inducible nitric oxide synthase expression [71].

Data from clinical studies on patients with myeloma [72] and patients on haemodialysis [73] have shown that EPO has direct effects on immunity. In a murine model of myeloma, EPO promotes the development of an antitumour specific immune response via activated CD8+ T cells [74]. Little is known on the expression and signalling of the EpoR in immune cells, however, as the classical EpoR was not detected on human lymphocytes by proofreading PCR [75] and these observed effects may be mediated by other cells. This is supported by the expression and role of the EpoR on macrophages during wound repair [76].

While positive results in animal models do not always correlate with clinical outcomes, it appears that EPO has significant cytoprotective effects mediated by anti-apoptotic and immune mechanisms that could be beneficial in sepsis syndromes. These effects remain to be confirmed in clinical practice.

Clinical studies of erythropoietin

In septic patients, EPO concentrations are elevated above control levels [77-79] but response to anaemia is blunted [80,81], with lower levels than in otherwise well, anaemic patients. In clinical studies, concentrations of 300 to 500 IU/kg have been used, with peak serum levels reaching over 5,500 U/l in one trial and 200 times greater than control in another [82,83]. Once-weekly dosing with 40,000 IU EPO in intensive care patients gave mean serum levels upward of 800 IU/l in the blood, similar to levels found in healthy controls [84,85]. This compares with peak levels of 150 IU/l in septic shock patients [79].

Many patients with severe sepsis require treatment in critical care units. There are high-quality data on the effects of EPO on transfusion requirements in critical illness. Anaemia in critically ill patients evolves over time such that transfusion is required in 35% of patients requiring intensive care for > 5 days [86].

The largest randomised study of EPO in critically ill patients had significant numbers of septic patients (188/1,460 patients) [87,88]. Recruitment was 48 hours after intensive care unit admission with EPO being commenced between days 3 and 5. There was no a priori analysis of mortality in septic patients or on total pressor requirements. EPO was associated with a lower mortality at day 29 (8.5% vs. 11.4%), and an analysis of the 793 trauma patients in this study did show a marked reduction in mortality (relative risk, 0.4; 95% confidence interval, 0.23 to 0.69). It is interesting to speculate why this might be. Animal models of traumatic and compressive peripheral and central nerve injury and models of wound healing show consistent cytoprotective effects, with EPO correlating with reduced apoptosis, improved wound healing and reduced inflammation [11,89]. In addition, rat models of haemorrhagic shock show improvements in haemodynamic stability and markers of organ dysfunction [62,90]. These effects may underlie the improved outcome; however, clinically relevant thrombotic events were commoner in EPO-treated patients, with a hazard ratio of 1.41 (95% confidence interval, 1.06 to 1.86) occurring in 120/728 patients in the EPO-treated group versus 83/720 in the control group. This prothrombotic tendency has been recognised in other conditions (see below) and raises concerns about target haemoglobin concentrations and dosing.

A meta-analysis identified nine trials of EPO in acutely unwell patients [91], a significant minority of whom had sepsis [84,87,88,92-97]. Recruitment into these studies occurred when either a transfusion trigger was met or after a given time in intensive care (see Table 1). No mortality benefit (odds ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.65 to 1.01) was observed among the studies of high methodological quality. Importantly, EPO doses > 40,000 units weekly were associated with a trend towards more harm. Transfusion independence showed an odds ratio of 0.73 (95% confidence interval, 0.64 to 0.84) in favour of EPO, with a reduction of 0.41 units of blood transfused. Interpretation of these data in light of this discussion is problematic as anticipated nonhaemopoeitic benefits of EPO are likely to accrue from administration in the early stages of sepsis. Nonetheless, data from these studies inform on potential harm, dosing and pharmacokinetics. In addition, changes in transfusion practice in 1999 accepting a lower threshold for transfusion make studies before and after this date difficult to reconcile [98].

Table 1.

Summary of trials of erythropoietin in acutely critically ill patients

| Year | Reference | n total | n sepsis | Enrolment | Dose | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | Still and colleagues [96] | 40 | 0 | > 3 days | 150 IU/kg three times/week | 30 days |

| 1998 | Gabriel and colleagues [93] | 21 | ns | ICU admission | 600 IU/kg three times/week | Maximum 3 weeks |

| 1999 | Corwin and colleagues [92] | 80 | 6 | Day 3 | 300 IU/kg daily for 5 days | Maximum 6 weeks |

| 2000 | van Iperen and colleagues [97] | 36 | 23 | Hb < 11.2 g/dl | 300 IU/kg alternate days for 5 days | 5 doses |

| 2002 | Corwin and colleagues [87] | 1,352 | 105 | Day 3 | 40,000 IU/week | Maximum 3 weeks |

| 2005 | Georgopoulos and colleagues [94] | 148 | ns | Hb < 12.0 g/dl | 40,000 IU/week | Maximum 3 weeks |

| 2006 | Vincent and colleagues [84] | 68 | 14 | HCT < 0.38 | 40,000 IU/week | Maximum 4 weeks |

| 2006 | Silver and colleagues [95] | 86 | 25 | < 7 days | 40,000 IU/week | Maximum 12 weeks |

| 2007 | Corwin and colleagues [88] | 1,460 | 188 | Day 3/4 | 40,000 U/week | Maximum 3 weeks |

Number of patients with sepsis is shown and the timing of erythropoietin use. Hb, haemoglobin; HCT, haematocrit; ICU, intensive care unit; ns, not specified.

Clinical data supporting a cytoprotective effect have been shown in cerebrovascular accidents, with those patients administered EPO 8 hours after the onset of their stroke having better clinical and radiological outcomes [82]. Following animal evidence of antiapoptotic effects in cerebral malaria [99,100], EPO is currently being investigated as an adjunctive treatment in a phase III trial of cerebral malaria in children in Mali [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00697164].

Potential side effects of erythropoietin

Speculation on the benefit of a novel treatment has to be weighed against potential harm. Data from renal patients suggest that aiming for haemoglobin concentrations > 12 g/dl worsens the risk of thrombotic events [101,102]. An increase in clinically relevant thrombotic events has been shown in critically ill patients, with a 1.5 times increase (7.8% vs. 5.3%) in deep vein thrombosis and a 2.5 times increase in myocardial infarction (2.1% vs. 0.8%) [91]. This occurred in the presence of haemoglobin concentrations < 10 g/dl, suggesting that the prothrombotic effects are not wholly dependent on blood viscosity but reflect platelet and endothelial cell changes [13]. As microvascular thrombosis is felt to contribute to organ failure and coagulopathy in sepsis [1,2], EPO could exacerbate this problem. The use of non-erythropoietic derivatives such as CEPO may avoid many of the adverse effects observed with EPO.

EPO has been associated with worsening of hypertension and hypertensive encephalopathy [13] but these are less common with treatment nowadays. As sepsis is associated with vasodilatory shock, vasopressor effects could be seen as a positive side effect (see above).

The use of EPO has been shown to worsen outcome in certain cancers due to increased thromboembolic risk and possibly EPO-induced tumour progression [103]. This observation raises concerns over EPO use in patients with malignancies who develop sepsis. If used earlier in the course of sepsis, EPO may uncover other unwanted side effects. Serious problems such as pure red cell aplasia due to EPO antibodies are fortunately rare [13] but clinicians using this drug in a new way should monitor closely for adverse side effects.

Conclusion

Attempts at immune modulation in sepsis have proved disappointing for many years, leading to a reappraisal of the mechanisms underlying sepsis in the search for novel therapies. Apoptosis is pivotal in the relative immuno-suppression that can lead to secondary infection and superinfection in sepsis. EPO has known anti-apoptotic effects that have shown, in both animal and clinical models of disease, to translate into clear cytoprotective effects. Coupled with this observation, EPO appears to have in vitro and in vivo effects on vasomotor function, augmenting the effects of other mediators such as catecholamines and endothelins. Reliable clinical data in critically ill patients have led to useful information on the pharmacokinetics [84,85] and the potential for harm [87,88,91].

An observational, prospective cohort study is currently underway to examine the effects of EPO on microvascular inflammatory response in severe sepsis [Clinical trials. gov identifier NCT01087450]. We argue that the weight of evidence has reached a point where further phase II and III clinical trials on EPO would seem the obvious next step. We believe most benefit would accrue from the administration of EPO within 24 hours of the onset of sepsis and organ dysfunction. Optimal absorption would be via the intravenous route and dosing could be guided from clinical studies where ranges between 150 and 600 IU/kg have been used previously. We would suggest doses of 400 IU/kg given on consecutive days for 3 days with close monitoring for thromboembolic side effects [82,92,93,97].

Abbreviations

Bcl-2: B-cell lymphoma protein 2; CEPO: carbamylated erythropoietin; EPO: erythropoietin; EpoR: erythropoietin receptor; IL: interleukin; Jak-2: Janus tyrosine kinase 2; MAP: mean arterial pressure; NF: nuclear factor; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; TNF: tumour necrosis factor.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Andrew P Walden, Email: apwalden@hotmail.com.

J Duncan Young, Email: edward.sharples@orh.nhs.uk.

Edward Sharples, Email: duncan.young@nda.ox.ac.uk.

References

- Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:138–150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA. Management of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1699–1713. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letarte J, Longo CJ, Pelletier J, Nabonne B, Fisher HN. Patient characteristics and costs of severe sepsis and septic shock in Quebec. J Crit Care. 2002;17:39–49. doi: 10.1053/jcrc.2002.33028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart K, Karzai W. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in sepsis: update on clinical trials and lessons learned. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7 Suppl):S121–S125. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefering R, Neugebauer EA. Steroid controversy in sepsis and septic shock: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1294–1303. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199507000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D, Moreno R, Singer M, Freivogel K, Weiss YG, Benbenishty J, Kalenka A, Forst H, Laterre PF, Reinhart K, Cuthbertson BH, Payen D, Briegel J. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:111–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss RS, Tinsley KW, Swanson PE, Schmieg RE, Hui JJ, Chang KC, Osborne DF, Freeman BD, Cobb JP, Buchman TG, Karl IE. Sepsis-induced apoptosis causes progressive profound depletion of B and CD4+ T lymphocytes in humans. J Immunol. 2001;166:6952–6963. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meakins JL, Pietsch JB, Bubenick O, Kelly R, Rode H, Gordon J, MacLean LD. Delayed hypersensitivity: indicator of acquired failure of host defenses in sepsis and trauma. Ann Surg. 1977;186:241–250. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197709000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberholzer A, Oberholzer C, Moldawer LL. Sepsis syndromes: understanding the role of innate and acquired immunity. Shock. 2001;16:83–96. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200116020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines M, Cerami A. Emerging biological roles for erythropoietin in the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:484–494. doi: 10.1038/nrn1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi P, Mengozzi M. Activities of erythropoietin on tumors: an immunological perspective. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1427–1430. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcasoy MO. The non-haematopoietic biological effects of erythropoietin. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:14–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savill J. Apoptosis in resolution of inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61:375–380. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute-Bello G, Liles WC, Radella F, Steinberg KP, Ruzinski JT, Jonas M, Chi EY, Hudson LD, Martin TR. Neutrophil apoptosis in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1969–1977. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.6.96-12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez MF, Watson RW, Parodo J, Evans D, Foster D, Steinberg M, Rotstein OD, Marshall JC. Dysregulated expression of neutrophil apoptosis in the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Arch Surg. 1997;132:1263–1269; discussion 1269-1270. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430360009002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss RS, Swanson PE, Freeman BD, Tinsley KW, Cobb JP, Matuschak GM, Buchman TG, Karl IE. Apoptotic cell death in patients with sepsis, shock, and multiple organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1230–1251. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remick DG. Pathophysiology of sepsis. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1435–1444. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle WG, Pemberton RM, Robinson D, Livingston DH, Rodriguez JL, Polk HC. Lymphocyte subset responses to trauma and sepsis. J Trauma. 1993;35:844–849. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199312000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Tulzo Y, Pangault C, Gacouin A, Guilloux V, Tribut O, Amiot L, Tattevin P, Thomas R, Fauchet R, Drenou B. Early circulating lymphocyte apoptosis in human septic shock is associated with poor outcome. Shock. 2002;18:487–494. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss RS, Chang KC, Grayson MH, Tinsley KW, Dunne BS, Davis CG, Osborne DF, Karl IE. Adoptive transfer of apoptotic splenocytes worsens survival, whereas adoptive transfer of necrotic splenocytes improves survival in sepsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6724–6729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031788100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CS, Song GY, Lomas J, Simms HH, Chaudry IH, Ayala A. Inhibition of Fas/Fas ligand signaling improves septic survival: differential effects on macrophage apoptotic and functional capacity. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:344–351. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0102006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CS, Yang S, Song GY, Lomas J, Wang P, Simms HH, Chaudry IH, Ayala A. Inhibition of Fas signaling prevents hepatic injury and improves organ blood flow during sepsis. Surgery. 2001;130:339–345. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.116540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss RS, Swanson PE, Knudson CM, Chang KC, Cobb JP, Osborne DF, Zollner KM, Buchman TG, Korsmeyer SJ, Karl IE. Overexpression of Bcl-2 in transgenic mice decreases apoptosis and improves survival in sepsis. J Immunol. 1999;162:4148–4156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss RS, Chang KC, Swanson PE, Tinsley KW, Hui JJ, Klender P, Xanthoudakis S, Roy S, Black C, Grimm E, Aspiotis R, Han Y, Nicholson DW, Karl IE. Caspase inhibitors improve survival in sepsis: a critical role of the lymphocyte. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:496–501. doi: 10.1038/82741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki M, Kuwano K, Hagimoto N, Matsuba T, Kunitake R, Tanaka T, Maeyama T, Hara N. Protection from lethal apoptosis in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice by a caspase inhibitor. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:597–603. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64570-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey EA, Finlay BB. Lipopolysaccharide induces apoptosis in a bovine endothelial cell line via a soluble CD14 dependent pathway. Microb Pathog. 1998;24:101–109. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylte MJ, Corbeil LB, Inzana TJ, Czuprynski CJ. Haemophilus somnus induces apoptosis in bovine endothelial cells in vitro. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1650–1660. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1650-1660.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Yee E, Harlan JM, Wong F, Karsan A. Lipopolysaccharide induces the antiapoptotic molecules, A1 and A20, in microvascular endothelial cells. Blood. 1998;92:2759–2765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies BE, Kourteva I. Internalization of Staphylococcus aureus by endothelial cells induces apoptosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5994–5998. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5994-5998.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlman TH, Harlan JM. Human endothelial cell response to lipopolysaccharide, interleukin-1, and tumor necrosis factor is regulated by protein synthesis. Cell Immunol. 1989;119:41–52. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(89)90222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss RS, Tinsley KW, Swanson PE, Karl IE. Endothelial cell apoptosis in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(5 Suppl):S225–S228. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haimovitz-Friedman A, Cordon-Cardo C, Bayoumy S, Garzotto M, McLoughlin M, Gallily R, Edwards CK, Schuchman EH, Fuks Z, Kolesnick R. Lipopolysaccharide induces disseminated endothelial apoptosis requiring ceramide generation. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1831–1841. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.11.1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer S, Brenner T, Bopp C, Steppan J, Lichtenstern C, Weitz J, Bruckner T, Martin E, Hoffmann U, Weigand MA. Cell death serum biomarkers are early predictors for survival in severe septic patients with hepatic dysfunction. Crit Care. 2009;13:R93. doi: 10.1186/cc7923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JW. Erythropoietin: physiology and pharmacology update. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2003;228:1–14. doi: 10.1177/153537020322800101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winearls CG, Oliver DO, Pippard MJ, Reid C, Downing MR, Cotes PM. Effect of human erythropoietin derived from recombinant DNA on the anaemia of patients maintained by chronic haemodialysis. Lancet. 1986;2:1175–1178. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)92192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschbach JW, Egrie JC, Downing MR, Browne JK, Adamson JW. Correction of the anemia of end-stage renal disease with recombinant human erythropoietin. Results of a combined phase I and II clinical trial. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:73–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198701083160203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitson KS, McNeill LA, Schofield CJ. Modulating the hypoxia-inducible factor signaling pathway: applications from cardiovascular disease to cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:821–833. doi: 10.2174/1381612043452884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong ZZ, Kang JQ, Maiese K. Hematopoietic factor erythropoietin fosters neuroprotection through novel signal transduction cascades. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:503–514. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200205000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong ZZ, Kang JQ, Maiese K. Angiogenesis and plasticity: role of erythropoietin in vascular systems. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2002;11:863–871. doi: 10.1089/152581602321080529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genc S, Koroglu TF, Genc K. Erythropoietin as a novel neuroprotectant. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2004;22:105–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakanaka M, Wen TC, Matsuda S, Masuda S, Morishita E, Nagao M, Sasaki R. In vivo evidence that erythropoietin protects neurons from ischemic damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4635–4640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiese K, Li F, Chong ZZ. New avenues of exploration for erythropoietin. JAMA. 2005;293:90–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharples EJ, Yaqoob MM. Erythropoietin in experimental acute renal failure. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2006;104:e83–e88. doi: 10.1159/000094546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leist M, Ghezzi P, Grasso G, Bianchi R, Villa P, Fratelli M, Savino C, Bianchi M, Nielsen J, Gerwien J, Kallunki P, Larsen AK, Helboe L, Christensen S, Pedersen LO, Nielsen M, Torup L, Sager T, Sfacteria A, Erbayraktar S, Erbayraktar Z, Gokmen N, Yilmaz O, Cerami-Hand C, Xie QW, Coleman T, Cerami A, Brines M. Derivatives of erythropoietin that are tissue protective but not erythropoietic. Science. 2004;305:239–242. doi: 10.1126/science.1098313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiordaliso F, Chimenti S, Staszewsky L, Bai A, Carlo E, Cuccovillo I, Doni M, Mengozzi M, Tonelli R, Ghezzi P, Coleman T, Brines M, Cerami A, Latini R. A nonerythropoietic derivative of erythropoietin protects the myocardium from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2046–2051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409329102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman TR, Westenfelder C, Togel FE, Yang Y, Hu Z, Swenson L, Leuvenink HG, Ploeg RJ, d'Uscio LV, Katusic ZS, Ghezzi P, Zanetti A, Kaushansky K, Fox NE, Cerami A, Brines M. Cytoprotective doses of erythropoietin or carbamylated erythropoietin have markedly different procoagulant and vasoactive activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5965–5970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601377103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines M, Patel NS, Villa P, Brines C, Mennini T, De Paola M, Erbayraktar Z, Erbayraktar S, Sepodes B, Thiemermann C, Ghezzi P, Yamin M, Hand CC, Xie QW, Coleman T, Cerami A. Nonerythropoietic, tissue-protective peptides derived from the tertiary structure of erythropoietin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10925–10930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805594105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry DW, Oliver JA. The pathogenesis of vasodilatory shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:588–595. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra002709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellinger RP, Carlet JM, Masur H, Gerlach H, Calandra T, Cohen J, Gea-Banacloche J, Keh D, Marshall JC, Parker MM, Ramsay G, Zimmerman JL, Vincent JL, Levy MM. Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:858–873. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000117317.18092.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes CL, Walley KR, Chittock DR, Lehman T, Russell JA. The effects of vasopressin on hemodynamics and renal function in severe septic shock: a case series. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:1416–1421. doi: 10.1007/s001340101014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA, Walley KR, Singer J, Gordon AC, Hebert PC, Cooper DJ, Holmes CL, Mehta S, Granton JT, Storms MM, Cook DJ, Presneill JJ, Ayers D. Vasopressin versus norepinephrine infusion in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:877–887. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschio G. Erythropoietin and systemic hypertension. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995;10(Suppl 2):74–79. doi: 10.1093/ndt/10.supp2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KJ, Bleyer AJ, Little WC, Sane DC. The cardiovascular effects of erythropoietin. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;59:538–548. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(03)00468-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neusser M, Tepel M, Zidek W. Erythropoietin increases cytosolic free calcium concentration in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:1233–1236. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.7.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimoto T, Kusano E, Fujita N, Okada K, Saito O, Ono S, Ando Y, Homma S, Saito T, Asano Y. Erythropoietin modulates angiotensin II- or noradrenaline-induced Ca(2+) mobilization in cultured rat vascular smooth-muscle cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:491–499. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JD, Zhang Z, Zhu JH, Lee DB, Ward HJ, Jamgotchian N, Hu MS, Fredal A, Giordani M, Eggena P. Erythropoietin upregulates angiotensin receptors in cultured rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J Hypertens. 1998;16(12 Pt 1):1749–1757. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816120-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusano E, Akimoto T, Umino T, Yanagiba S, Inoue M, Ito C, Ando Y, Asano Y. Modulation of endothelin-1-induced cytosolic free calcium mobilization and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by erythropoietin in vascular smooth muscle cells. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2001;24:192–200. doi: 10.1159/000054227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimoto T, Kusano E, Muto S, Fujita N, Okada K, Saito T, Komatsu N, Ono S, Ebata S, Ando Y, Homma S, Asano Y. The effect of erythropoietin on interleukin-1β mediated increase in nitric oxide synthesis in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Hypertens. 1999;17:1249–1256. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917090-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusano E, Akimoto T, Inoue M, Masunaga Y, Umino T, Ono S, Ando Y, Homma S, Muto S, Komatsu N, Asano Y. Human recombinant erythropoietin inhibits interleukin-1β-stimulated nitric oxide and cyclic guanosine monophosphate production in cultured rat vascular smooth-muscle cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:597–603. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.3.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich S, Rahn KH, Zidek W. Direct vasopressor effect of recombinant human erythropoietin on renal resistance vessels. Kidney Int. 1991;39:259–265. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buemi M, Allegra A, Squadrito F, Buemi AL, Lagana A, Aloisi C, Frisina N. Effects of intravenous administration of recombinant human erythropoietin in rats subject to hemorrhagic shock. Nephron. 1993;65:440–443. doi: 10.1159/000187526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita K, Itoh H, Sawada N, Fukunaga Y, Sone M, Yamahara K, Yurugi T, Nakao K. Adrenomedullin promotes proliferation and migration of cultured endothelial cells. Hypertens Res. 2003;26(Suppl):S93–S98. doi: 10.1291/hypres.26.S93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hand MF, Haynes WG, Johnstone HA, Anderton JL, Webb DJ. Erythropoietin enhances vascular responsiveness to norepinephrine in renal failure. Kidney Int. 1995;48:806–813. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allegra A, Galasso A, Siracusano L, Aloisi C, Corica F, Lagana A, Frisina N, Buemi M. Administration of recombinant erythropoietin determines increase of peripheral resistances in patients with hypovolemic shock. Nephron. 1996;74:431–432. doi: 10.1159/000189352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tascilar O, Cakmak GK, Tekin IO, Emre AU, Ucan BH, Bahadir B, Acikgoz S, Irkorucu O, Karakaya K, Balbaloglu H, Kertis G, Ankarali H, Comert M. Protective effects of erythropoietin against acute lung injury in a rat model of acute necrotizing pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:6172–6182. doi: 10.3748/wjg.13.6172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzzocrea S, Di Paola R, Mazzon E, Patel NS, Genovese T, Muia C, Crisafulli C, Caputi AP, Thiemermann C. Erythropoietin reduces the development of nonseptic shock induced by zymosan in mice. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1168–1177. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000207346.56477.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroglu TF, Yilmaz O, Ozer E, Baskin H, Gokmen N, Kumral A, Duman M, Ozkan H. Erythropoietin attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced splenic and thymic apoptosis in rats. Physiol Res. 2006;55:309–316. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.930791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra A, Bansal S, Wang W, Falk S, Zolty E, Schrier RW. Erythropoietin ameliorates renal dysfunction during endotoxaemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:2349–2353. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao R, Xenocostas A, Rui T, Yu P, Huang W, Rose J, Martin CM. Erythropoietin improves skeletal muscle microcirculation and tissue bioenergetics in a mouse sepsis model. Crit Care. 2007;11:R58. doi: 10.1186/cc5920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoshiba K, Onizawa S, Tsuji T, Nagai A. Therapeutic effects of erythropoietin in murine models of endotoxin shock. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:889–898. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819b8371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz O, Gil L, Lifshitz L, Prutchi-Sagiv S, Gassmann M, Mittelman M, Neumann D. Erythropoietin enhances immune responses in mice. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1584–1593. doi: 10.1002/eji.200637025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryl E, Mysliwska J, Debska-Slizien A, Trzonkowski P, Rachon D, Bullo B, Zdrojewski Z, Mysliwski A, Rutkowski B. Recombinant human erythropoietin stimulates production of interleukin 2 by whole blood cell cultures of hemodialysis patients. Artif Organs. 1999;23:809–816. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.1999.06177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelman M, Neumann D, Peled A, Kanter P, Haran-Ghera N. Erythropoietin induces tumor regression and antitumor immune responses in murine myeloma models. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5181–5186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081275298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prutchi-Sagiv S, Golishevsky N, Oster HS, Katz O, Cohen A, Naparstek E, Neumann D, Mittelman M. Erythropoietin treatment in advanced multiple myeloma is associated with improved immunological functions: could it be beneficial in early disease? Br J Haematol. 2006;135:660–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroon ZA, Amin K, Jiang X, Arcasoy MO. A novel role for erythropoietin during fibrin-induced wound-healing response. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63459-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel J, Spannbrucker N, Fandrey J, Jelkmann W. Serum erythropoietin levels in patients with sepsis and septic shock. Eur J Haematol. 1996;57:359–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1996.tb01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamion F, Le Cam-Duchez V, Menard JF, Girault C, Coquerel A, Bonmarchand G. Erythropoietin and renin as biological markers in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2004;8:R328–R335. doi: 10.1186/cc2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamion F, Le Cam-Duchez V, Menard JF, Girault C, Coquerel A, Bonmarchand G. Serum erythropoietin levels in septic shock. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2005;33:578–584. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0503300505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobisch-Hagen P, Wiedermann F, Mayr A, Fries D, Jelkmann W, Fuchs D, Hasibeder W, Mutz N, Klingler A, Schobersberger W. Blunted erythropoietic response to anemia in multiply traumatized patients. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:743–747. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200104000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogiers P, Zhang H, Leeman M, Nagler J, Neels H, Melot C, Vincent JL. Erythropoietin response is blunted in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:159–162. doi: 10.1007/s001340050310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich H, Hasselblatt M, Dembowski C, Cepek L, Lewczuk P, Stiefel M, Rustenbeck HH, Breiter N, Jacob S, Knerlich F, Bohn M, Poser W, Ruther E, Kochen M, Gefeller O, Gleiter C, Wessel TC, De Ryck M, Itri L, Prange H, Cerami A, Brines M, Siren AL. Erythropoietin therapy for acute stroke is both safe and beneficial. Mol Med. 2002;8:495–505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsic E, van der Meer P, Voors AA, Westenbrink BD, van den Heuvel AF, de Boer HC, van Zonneveld AJ, Schoemaker RG, van Gilst WH, Zijlstra F, van Veldhuisen DJ. A single bolus of a long-acting erythropoietin analogue darbepoetin alfa in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a randomized feasibility and safety study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2006;20:135–141. doi: 10.1007/s10557-006-7680-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JL, Spapen HD, Creteur J, Piagnerelli M, Hubloue I, Diltoer M, Roman A, Stevens E, Vercammen E, Beaver JS. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of once-weekly subcutaneous epoetin alfa in critically ill patients: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1661–1667. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217919.22155.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung W, Minton N, Gunawardena K. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of epoetin alfa once weekly and three times weekly. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;57:411–418. doi: 10.1007/s002280100324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JL, Baron JF, Reinhart K, Gattinoni L, Thijs L, Webb A, Meier-Hellmann A, Nollet G, Peres-Bota D. Anemia and blood transfusion in critically ill patients. JAMA. 2002;288:1499–1507. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin HL, Gettinger A, Pearl RG, Fink MP, Levy MM, Shapiro MJ, Corwin MJ, Colton T. Efficacy of recombinant human erythropoietin in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2827–2835. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin HL, Gettinger A, Fabian TC, May A, Pearl RG, Heard S, An R, Bowers PJ, Burton P, Klausner MA, Corwin MJ. Efficacy and safety of epoetin alfa in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:965–976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi P, Brines M. Erythropoietin as an antiapoptotic, tissue-protective cytokine. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11(Suppl 1):S37–S44. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WT, Lin NT, Subeq YM, Lee RP, Chen IH, Hsu BG. Erythropoietin protects severe haemorrhagic shock-induced organ damage in conscious rats. Injury. 2010;41:818–824. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarychanski R, Turgeon AF, McIntyre L, Fergusson DA. Erythropoietin-receptor agonists in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. CMAJ. 2007;177:725–734. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin HL, Gettinger A, Rodriguez RM, Pearl RG, Gubler KD, Enny C, Colton T, Corwin MJ. Efficacy of recombinant human erythropoietin in the critically ill patient: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2346–2350. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199911000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel A, Kozek S, Chiari A, Fitzgerald R, Grabner C, Geissler K, Zimpfer M, Stockenhuber F, Bircher NG. High-dose recombinant human erythropoietin stimulates reticulocyte production in patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. J Trauma. 1998;44:361–367. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199802000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulos D, Matamis D, Routsi C, Michalopoulos A, Maggina N, Dimopoulos G, Zakynthinos E, Nakos G, Thomopoulos G, Mandragos K, Maniatis A. Recombinant human erythropoietin therapy in critically ill patients: a dose-response study [ISRCTN48523317] Crit Care. 2005;9:R508–R515. doi: 10.1186/cc3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver M, Corwin MJ, Bazan A, Gettinger A, Enny C, Corwin HL. Efficacy of recombinant human erythropoietin in critically ill patients admitted to a long-term acute care facility: a randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled trial. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2310–2316. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000233873.17954.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Still JM, Belcher K, Law EJ, Thompson W, Jordan M, Lewis M, Saffle J, Hunt J, Purdue GF, Waymack JP, DeClement F, Kagan R, Chen A. A double-blinded prospective evaluation of recombinant human erythropoietin in acutely burned patients. J Trauma. 1995;38:233–236. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199502000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Iperen CE, Gaillard CA, Kraaijenhagen RJ, Braam BG, Marx JJ, van de Wiel A. Response of erythropoiesis and iron metabolism to recombinant human erythropoietin in intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2773–2778. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, Marshall J, Martin C, Pagliarello G, Tweeddale M, Schweitzer I, Yetisir E. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409–417. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese L, Hempel C, Penkowa M, Kirkby N, Kurtzhals JA. Recombinant human erythropoietin increases survival and reduces neuronal apoptosis in a murine model of cerebral malaria. Malar J. 2008;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu AL, Ferrandiz J, Kaiser K, Latour C, Picot S. Artesunate-erythropoietin combination for murine cerebral malaria treatment. Acta Trop. 2008;106:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besarab A, Bolton WK, Browne JK, Egrie JC, Nissenson AR, Okamoto DM, Schwab SJ, Goodkin DA. The effects of normal as compared with low hematocrit values in patients with cardiac disease who are receiving hemodialysis and epoetin. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:584–590. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808273390903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phrommintikul A, Haas SJ, Elsik M, Krum H. Mortality and target haemoglobin concentrations in anaemic patients with chronic kidney disease treated with erythropoietin: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;369:381–388. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlius J, Wilson J, Seidenfeld J, Piper M, Schwarzer G, Sandercock J, Trelle S, Weingart O, Bayliss S, Brunskill S, Djulbegovic B, Benett CL, Langensiepen S, Hyde C, Engert E. Erythropoietin or darbepoetin for patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD003407. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003407.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]