Abstract

Given that immunoproteasome inhibitors are currently being developed for a variety of potent therapeutic purposes, the unique specificity of an α′,β′-epoxyketone peptide (UK101) towards the LMP2 subunit of the immunoproteasome (analogous to β5 subunit of the constitutive proteasome) has been investigated in this study for the first time by employing homology modeling, molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation, and molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) binding free energy calculations. Based on the simulated binding structures, the calculated binding free energies are in qualitative agreement with the corresponding experimental data and the selectivity of UK101 is explained reasonably. The observed selectivity of UK101 for the LMP2 subunit is rationalized by the requirement for both a linear hydrocarbon chain at the N-terminus and a bulky group at the C-terminus of the inhibitor, because that LMP2 subunit has a much more favorable hydrophobic pocket interacting with the linear hydrocarbon chain, and the bulky group at the C-terminus has a steric clash with the Tyr 169 in β5 subunit. Finally, our results help to clarify why UK101 is specific to the LMP2 subunit of immunoproteasome, and this investigation should be valuable for rational design of more potent LMP2-specific inhibitors.

Introduction

Immunoproteasome has received considerable recent interest given its role in normal cellular processes and some diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD),1 Huntington’s disease (HD),2,3 multiple myeloma (MM),4,5 inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), autoimmune diseases, and cancers.6–9 Multiple myeloma is problematic due to its resistance to conventional drugs and side effects caused by nonspecific proteasome inhibitor drugs; targeted inhibition of the immunoproteasome has been proposed as an alternative strategy against this disorder.10 Thus, the development of specific inhibitors for the immunoproteasome is highly relevant, and many studies have focused on this topic.11–19

The proteasome plays a major role in the regulation of essential cellular processes such as transcription, cell cycle progression, and differentiation.20–22 The 20S constitutive (or regular) proteasome possesses multiple proteolytic activities, such as chymotrypsin-like (CT-L), trypsin-like (T-L), and caspase-like (C-L) activities. The immunoproteasome, which is expressed in cells of hematopoietic origin, is an alternative form of the constitutive proteasome present in all eukaryotic cells. The immunoproteasome can also be induced in non-hematopoietic cells following exposure to inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). Exposure of mammalian cells to these stimuli induces the synthesis of immunoproteasome-specific catalytic subunits LMP2/β1i, MECL1/β2i, and LMP7/β5i, which replace the constitutive proteasome counterparts Y/β1, Z/β2, and X/β5, respectively, to create the immunoproteasome.23

However, the detailed physiological role of the immunoproteasome beyond major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I antigen presentation remains poorly understood, due partly to the lack of small molecules that selectively inhibit the immunoproteasome. Thus far, a number of small-molecule inhibitors of the proteasomes have been developed for use as molecular probes of proteasome function and potential therapeutics; however, many lack specificity for the proteasomes.8,24 Furthermore, these small molecules are broadly active against both the constitutive proteasome and the immunoproteasome, thus compromising their utility as molecular probes of the immunoproteasome. It has been recently shown that an α′,β′-epoxyketone peptide (UK101) irreversibly inhibits the major catalytic subunit LMP2 of the immunoproteasome.12 Unlike the majority of currently available proteasome inhibitors, however, UK101 is specific for the LMP2 catalytic subunit. This study provided the first insights into the unique specificity of UK101 towards LMP2.

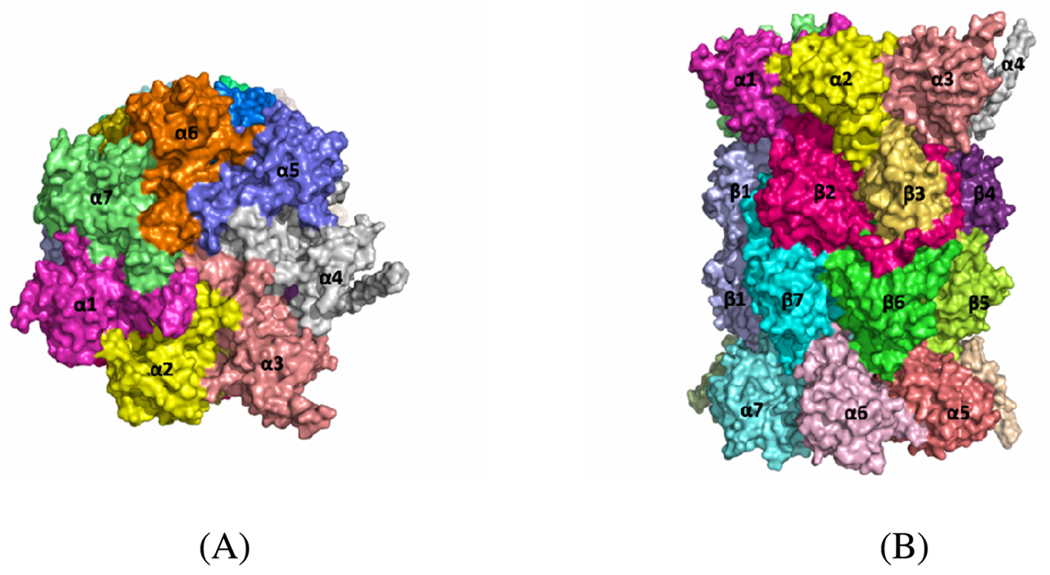

At present, the X-ray crystal structure of constitutive (or regular) proteasome is available, but the structure of immunoproteasome is not available. The X-ray crystal structure of the mammalian constitutive (or regular) 20S proteasome shows that it is composed of 28 subunits arranged in a unit as four homoheptameric rings.25 There are seven different subunits in each ring and it is organized as α7β7β7α7. Figure 1 shows the relative positions of the 28 subunits in the mammalian 20S proteasome (PDB code 1IRU). There are three proteasome β-type subunits with catalytic activities and all three of these subunits have an N-terminal threonine residue.25 The three catalytically active subunits are β1, β2, and β5 with the caspase-like, trypsin-like, and chymotrypsin-like activities in the constitutive proteasome, respectively.25 In the immunoproteasome these three specific catalytic subunits are replaced by LMP2/β1i, MECL1/β2i and LMP7/β5i. The X-ray structure of constitutive proteasome shows that the binding cavity in catalytic subunits is usually formed between two proteasome subunits.26 For example, the binding site for chymotrypsin-like activity is formed by association of β5 and β6 subunits.27 Another example is that the epoxide group of epoxomicin, a well-known inhibitor of proteasome, binds to the β5 active site by covalent interaction, and residues from the β6 subunit form a part of the binding cavity and interact with the other end (N-terminus) of epoxomicin.28

Figure 1.

Surface representation of the crystal structure of the mammalian 20S proteasome (PDB code 1IRU) from top (A) and side (B) views of the particle. The figure was prepared using PyMOL51

In the present study, we aimed to understand the unique specificity of UK101 towards the LMP2 subunit of the immunoproteasome. For this purpose, homology modeling, molecular docking, molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, and molecular mechanics–Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) binding energy calculations29 were employed. In addition to the newly discovered specific inhibitor UK101, epoxomicin was also included in this study as representative of proteasome inhibitors. The computational results reveal significant insights into the selectivity of UK101 towards the LMP2 subunit. Based on the docked structures and subsequent molecular dynamics simulation, the calculated binding free energies are in qualitative agreement with available experimental data. The results obtained in this study are expected to be valuable for rational design of novel, more selective and potent inhibitors of the LMP2 subunit.

Results and Discussions

Homology model of LMP2/MECL1 subunits

For the homology modeling, the sequences of LMP2 and MECL1 were first obtained from the Uniprot database.30 The sequence IDs for LMP2 and MECL1 are P28065 (residues 21–219) and P40306 (residues 40–273), respectively. In order to find a suitable template for modeling these two subunits, a BLAST search against the PDB database was carried out. Through the BLAST search, it was determined that the constitutive proteasome β1 subunit ‘H’ (PDB ID: 1IRUH) and β2 subunit ‘I’ (PDB ID: 1IRUI) are the most suitable templates for modeling LMP2 and MECL1, respectively. The sequence identity between LMP2 and MECL1 to the constitutive proteasome β1 subunit ‘H’ (PDB ID: 1IRUH) and β2 subunit ‘I’ (PDB ID: 1IRUI) are 61% and 57%, respectively. Then, SWISS-MODEL server was used to generate the homology model of the immunoproteasome subunits.31 Once the template and query sequence are given, the SWISS-MODEL server generates the homology model for the query sequence. The model quality was evaluated using the Ramachandran plot (from PROCHECK) in the SWISS-MODEL workspace.32,33 The Ramachandran plot for the LMP2 model (Figure S1 (A)) indicates that 88.5% of residues are in the most favored regions and 11.5% of residues are in additional allowed regions. The Ramachandran plot for the MECL1 model (Figure S1 (B)) indicates that 83.1% of residues are in the most favored regions, 16.4% of residues are in additional allowed regions, and 0.5% of residues are in generously allowed regions. There are no residues in disallowed regions in either model, which indicates that the homology models are acceptable.

Binding modes of UK101 with LMP2 and β5 subunits

To explore the best possible mode of ligand binding with the LMP2 and β5 subunits, molecular docking was performed using Glide.34 The Sander module of Amber (version 8) was used to carry out the MD simulations.35 The partial atomic charges for the ligand atoms were calculated using the RESP protocol36 after electrostatic potential calculations at Hartree-Fock (HF) level with 6–31G* basis set using Gaussian (03 version).37 Each protein-ligand binding complex was solvated and fully energy-minimized. The systems were carefully heated step by step and equilibrated before a production MD simulation run was carried out. The time-dependent geometric parameters were carefully examined to make sure that a stable MD trajectory was obtained for each simulated protein-ligand binding system; plots of root-mean-squares deviations (RMSD) versus the simulation time are provided in the Supporting Information (Figure S2). One hundred snapshots of the simulated structure within the stable MD trajectory were used in the binding free energy calculations using the MM-PBSA method.

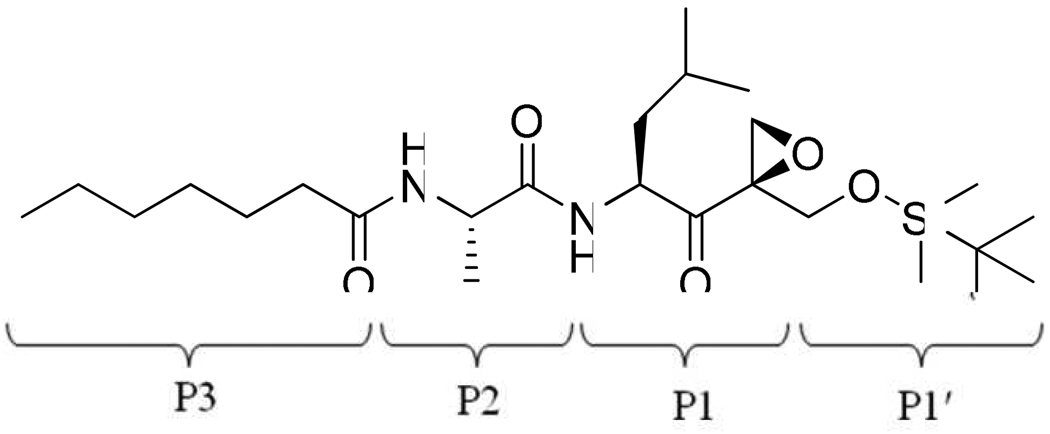

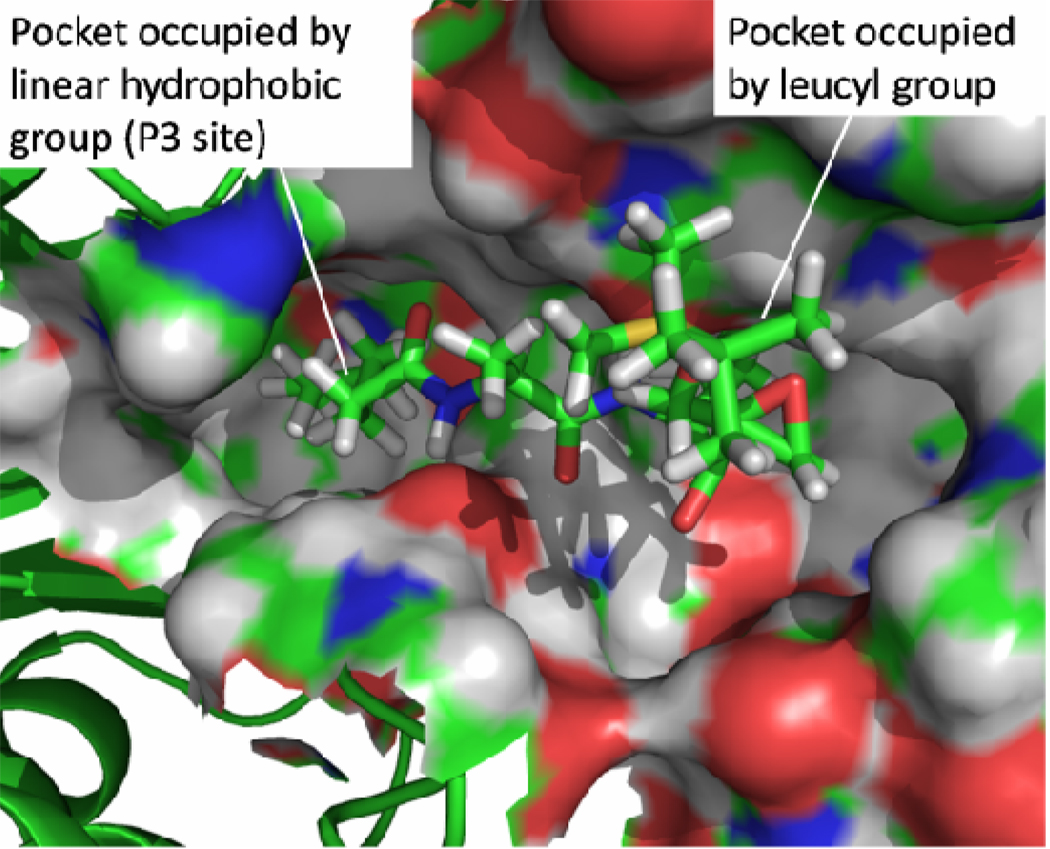

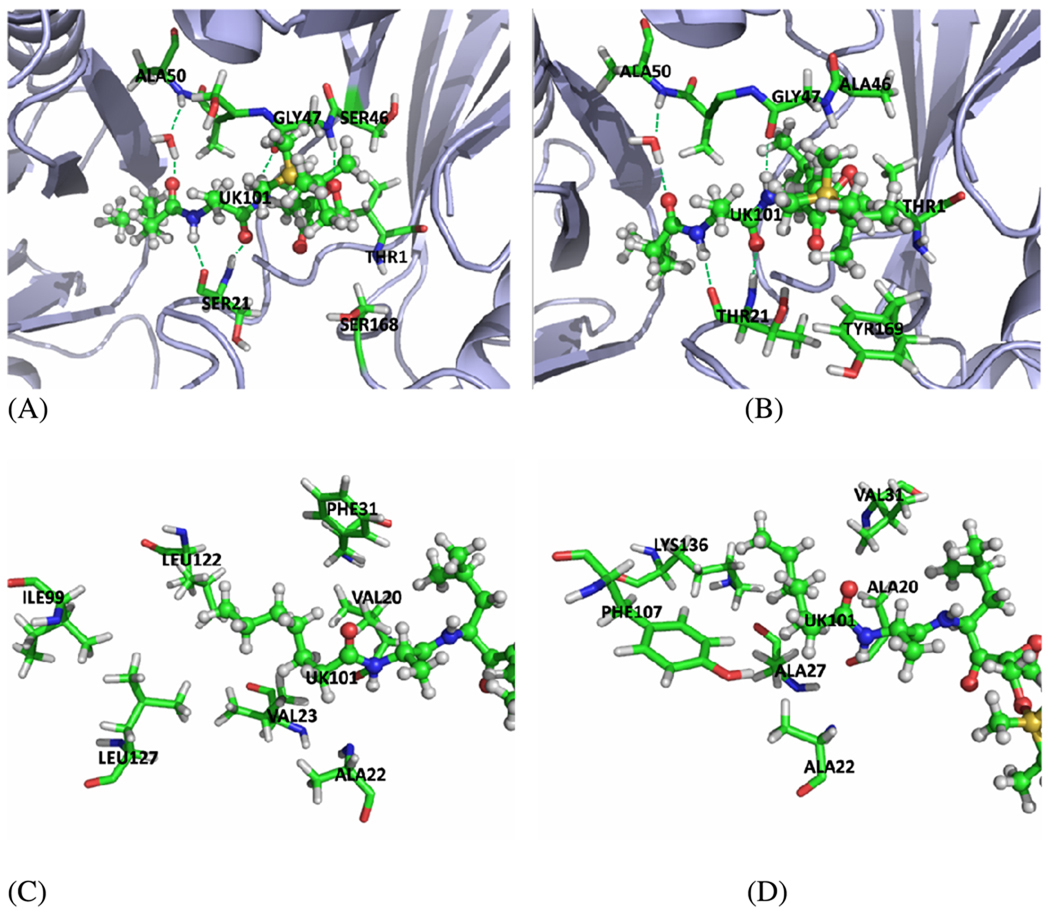

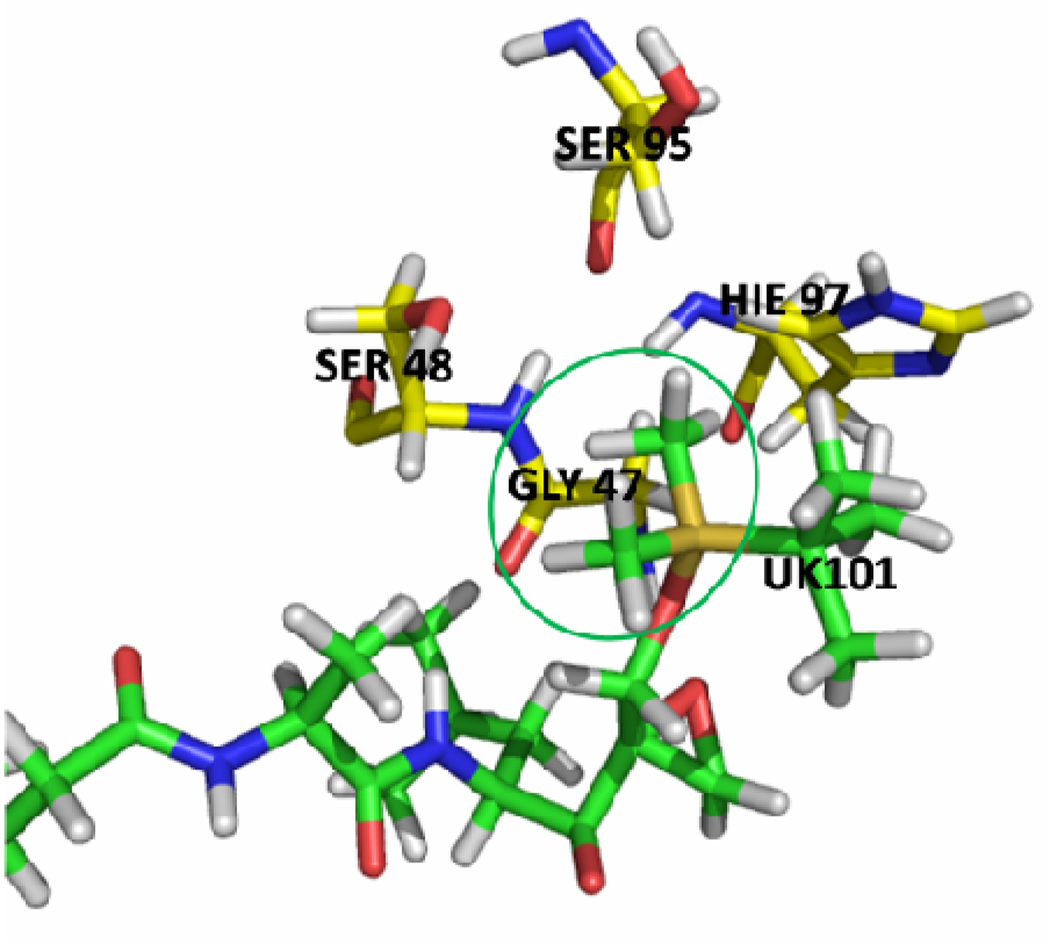

The calculations show that UK101 binds more favorably with LMP2 than with the β5 subunit. The calculated binding energies are shown in Table 1, and the values are in qualitative agreement with previously reported experimental results (Table 2). The structure of UK101 is shown in Figure 2. Based on the simulated structure, UK101 binds with LMP2 as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 5 (A). The binding mode shows that the leucyl group of UK101 (P1 segment) fits into the hydrophobic pocket made up of residues Phe 31, Leu 45, Ala 49, and Val 20. The tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBDMS) group of UK101 is located at the entrance of the active site. The TDBMS group is not involved in any specific interaction and is surrounded by residues Gly 47, Ser 48, Ser 95, and His 97. The binding study also shows that TBDMS is the optimal group to occupy this position. For example, the surface representation of the binding mode (Figure 3) and the stick representation of the surrounding residues around the TBDMS group of UK101 (Figure 4) show that replacing the TBDMS with the larger tert-butyldiphenylsilyl (TBDPS) will result in a steric clash with the surrounding residues. This observation is in agreement with previously reported experimental studies which show that introducing the TBDPS group results in loss of immunoproteasome inhibiting activity.12

Table 1.

Energetic results (kcal/mol) obtained from the MM-PBSA calculation at T = 298.15 K and P = 1 atm for EPX and UK101 binding with LMP2 and β5.

| Complex | ΔEele | ΔEvdw | ΔEMM | ΔGsolv | ΔEbind | −TΔS | ΔGbind |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPX-LMP2 | −37.03 | −57.98 | −95.01 | 57.18 | −37.83 | 22.20 | −15.63 |

| EPX-β5 | −35.07 | −59.27 | −94.34 | 57.08 | −37.27 | 23.13 | −14.15 |

| UK101-LMP2 | −28.29 | −56.97 | −85.25 | 49.14 | −36.11 | 22.29 | −13.83 |

| UK101-β5 | −23.86 | −55.15 | −79.01 | 46.42 | −32.59 | 25.01 | −7.59 |

Table 2.

Available experimental data for inhibition of 20S constitutive proteasome and immunoproteasome by epoxomicin and UK101.

| Compounds | Kobs/[I] (M−1S−1) a | IC50 (µM) b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20S regular proteasome |

20S immuno- proteasome |

LMP2-deficient cells |

LMP2-positive cells |

|

| Epoxomicin | 44,510 ± 7,000 | 3,044 ± 1,423 | 0.015 | 0.009 |

| UK101 | 49 ± 18 | 83 ± 27 | 14.34 | 2.04 |

Inhibition of chymotrypsin-like activity of the 20S constitutive proteasome and immunoproteasome. For the details see US Patent 7642369.

Inhibition of LMP2-positive/deficient cells by epoxomicin and UK101. See Ref. 12

Figure 2.

The chemical structure of UK101.

Figure 3.

Binding mode of UK101 with LMP2 subunit. The active site is shown in the form of a surface representation. The figure was prepared using PyMOL51

Figure 5.

The graph of UK101 binding with LMP2 andβ5 subunits and the hydrophobic pocket accommodate the n-heptanoyl group. UK101 is represented as ball-stick. (A) Binding mode of UK101 with the LMP2 subunit. (B) Binding mode of UK101 with the β5 subunit. (C) The residues composing the hydrophobic pocket accommodate the n-heptanoyl group of UK101 in the LMP2 subunit. (D) The residues composing the hydrophobic pocket accommodate the n-heptanoyl group of UK101 in the β5 subunit The figure was prepared using PyMOL51

Figure 4.

Stick representation of the surrounding residues around the TBDMS group of UK101. The figure was prepared using PyMOL 51

The terminal n-heptanoic group (P3 segment) of UK101 fits into a hydrophobic pocket at the interface of the LMP2 and MECL1 subunits. This pocket is composed of Val 20, Ala 22, Val 23, and Phe 31 from LMP2 on one side and of Ile 99, Leu 122, and Leu 127 from MECL1 on the other side (Figure 5(C)). The shape of this cavity favors the linear hydrophobic group very well. The carbonyl oxygen on the N-terminus of UK101 forms a hydrogen bonding network through a bridging water molecule to the backbone NH of Ala 50 (Figure 5(A)). The statistical occupancy of this hydrogen bond is up to ~84%, which indicates that it is a stable interaction. It is proposed that the strong hydrophobic interaction of the linear group fixes the n-heptanoic group, and consequently stabilizes the hydrogen bond.

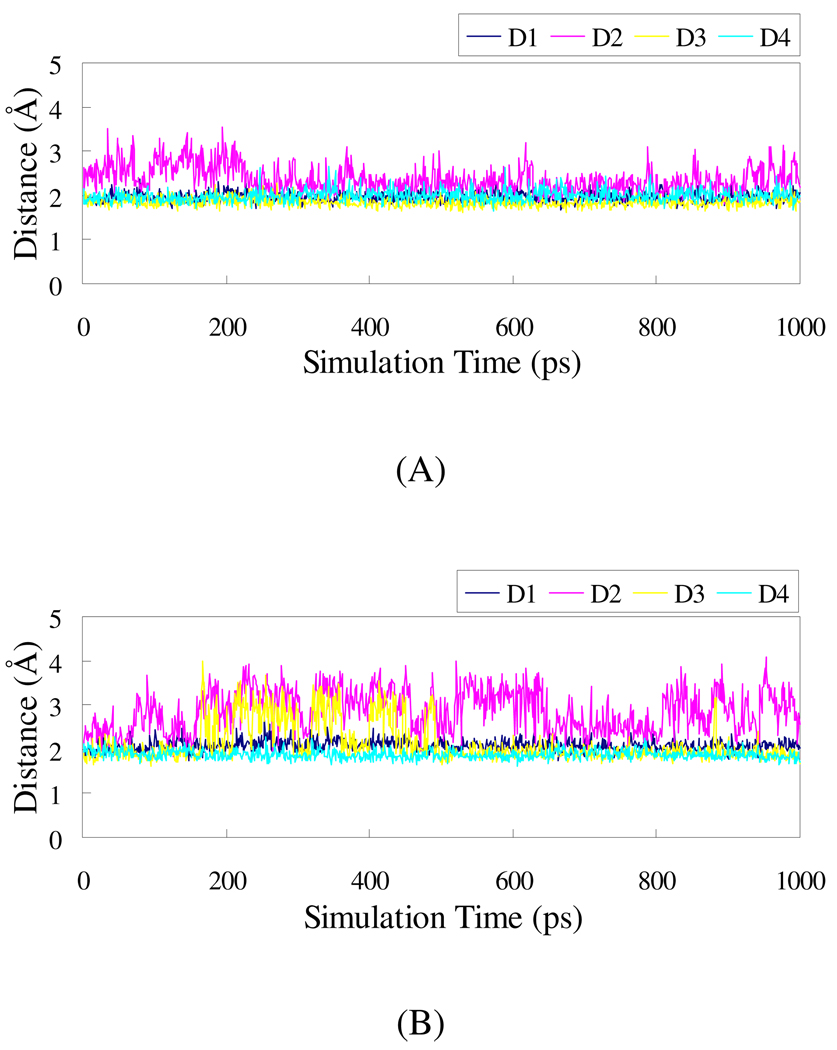

The amino group and carbonyl oxygen in the P2 segment of UK101 form hydrogen bonds with the carbonyl oxygen and NH of Ser 21 backbone, respectively. The C-terminal amino group of UK101 makes a stable hydrogen bond with carbonyl oxygen of Gly 47 backbone, and the epoxide oxygen of UK101 forms a hydrogen bond with backbone NH of Gly 47. Figure 6(A) shows the plots of the distances related to these hydrogen bonds versus the simulation time. It indicates that the hydrogen bonds are strong and stable at 2.1 Å (the distances with H) for UK101 binding with the LMP2 subunit.

Figure 6.

Plots of MD-simulated internuclear distances versus simulation time for UK101 with LMP2 (A) and β5 (B). D1 refers to the distance between the amino H in the P1 segment of UK101 and the carbonyl oxygen of Gly 47 backbone; D2 refers to the distance between the epoxyl oxygen and the H atom of GLY 47 backbone; D3 refers to the distance between the amino H in the P2 segment of UK101 and the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Ser 21 (for LMP2) or Thr 21 (for β5); D4 refers to the distance between the carbonyl oxygen in the P2 segment of UK101 and the amino H of Ser 21 (for LMP2) or Thr 21 (for β5).

In the case of UK101 binding with the β5 subunit, the n-heptanoic group has decreased interaction with β5, which is due to the much less favorable hydrophobic pocket composed of Ala 22, Ala 27, Ala 20, and Val 31 from the β5 subunit and Phe 107 and Lys 136 from the β6 subunit (Figure 5(D)). In contrast to the LMP2 subunit, almost all the hydrophobic residues Leu and Val are replaced with Ala (a smaller hydrophobic residue) or Lys (a hydrophilic residue), leading to the decrease in the hydrophobic interactions. As a result of the decreased hydrophobic interactions, the n-hexyl group is not stable. Consequently, the hydrogen bond between the carbonyl oxygen on the N-terminus of UK101 and the NH group of Ala 50 backbone is broken and has only ~53% occupancy in the β5 subunit. Therefore, the n-heptanoic group is not stable in the pocket.

In addition, in the case of the β5 subunit, the TBDMS group has a steric clash with Tyr 169 (Figure 5(B)), which forces the TBDMS group out of the active site and breaks the hydrogen bond between the epoxide oxygen of UK101 and the backbone NH of Gly 47. D2 in Figure 6(B) corresponds to the distance between the two atoms, demonstrating that the hydrogen bond has been broken. Compared to the LMP2 subunit, that distance in β5 increases and fluctuates largely, which is unfavorable for the nucleophilic attack by the amine group at the N-terminus. Because there is no such clash with the corresponding Ser 168 in the LMP2 subunit, the bulky group at the C-terminus of the inhibitor contributes to its selectivity for the LMP2 over the β5 subunit.

Insights from the reaction aspect

The α′,β′-epoxyketones are irreversible proteasome inhibitors because they covalently bind to the catalytic subunits by forming a morpholino ring between the α′,β′-epoxyketones pharmacophore and the nucleophilic threonine in the active site (Thr 1).8,9 The formation of the morpholino ring is apparently a two-step process, in light of the binding mode. First, the gamma oxygen of threonine attacks the carbonyl carbon atom of the epoxyketone pharmacophore, producing a hemiacetal. Then, threonine nitrogen opens the epoxide ring by nucleophilic attack on the quaternary carbon. In this study, the distances between the reactive atoms during the simulations are also examined in order to illustrate the selectivity of UK101 binding with LMP2.

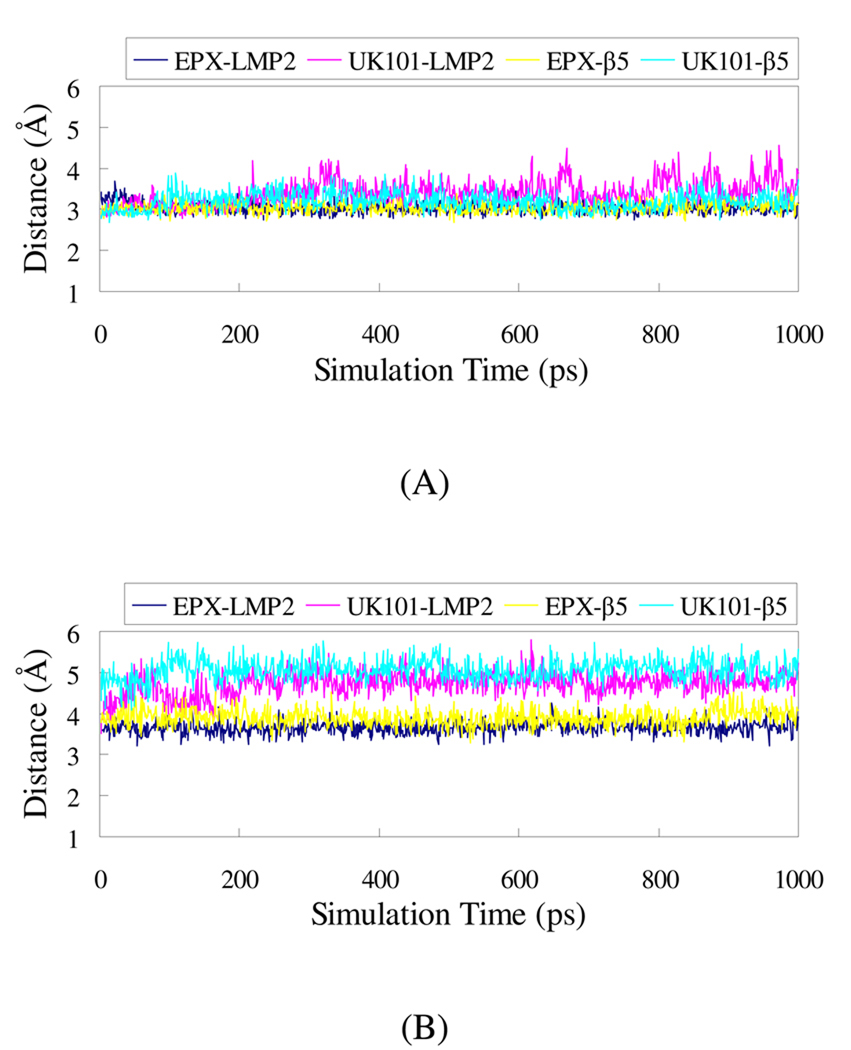

The plots of the distances between the reactive atoms are shown in Figure 7. Figure 7(A) displays these distances in the first step. It can be seen that the distances are similar for both epoxomicin and UK101 reacting with both LMP2 and β5 subunits in the first step. However, the first step is reversible and only after the second step can the catalytic activity be inhibited. The distance between the active atoms in the second step is shown in Figure 7(B). The distance between the active atoms is much longer for UK101 than for epoxomicin with both catalytic subunits. Thus, UK101 has lower activity than epoxomicin, which is consistent with experimental measurements (Table 2). Moreover, for UK101 interacting with the β5 subunit, the large TBDMS group must overcome the additional steric clash from Tyr 169, and the hydrogen bond between the epoxide oxygen of UK101 and the NH group of Gly 47 backbone is broken, which is unfavorable for the nucleophilic attack by the amine group on the N-terminus of the β5 subunit in comparison with the interaction between UK101 and the LMP2 subunit. This difference contributes to the selectivity of UK101 for LMP2.

Figure 7.

Plots of MD-simulated internuclear distances versus simulation time for EPX and UK101 with LMP2 and β5. (A) The distance between the carbonyl carbon adjacent to the epoxide group and the gamma oxygen of Thr 1. (B) The distance between the quaternary carbon in the epoxide group and the nitrogen of Thr1.

This study explains the molecular basis of selectivity for UK101 towards LMP2. A major significance of this work is that it provides the structural basis for UK101’s unique specificity for the LMP2 subunit of the immunoproteasome. It should be useful for future rational design of more potent and specific immunoproteasome inhibitors. The successful synthesis of these specific small molecules will be useful as investigative tools for dissecting the functions of the both types of proteasomes.

Conclusion

The modeled structure of proteasome catalytic subunits complexed with UK101 provides a framework to understand the intriguing selectivity of this compound. The observed selectivity of UK101 for LMP2 subunit is rationalized by the requirement for both a linear hydrocarbon chain at the N-terminus and a bulky residue at the C-terminus. Given that the immunoproteasome inhibitors are currently being developed for a variety of therapeutic purposes, the need for potent and selective small molecule immunoproteasome-specific inhibitors is well recognized. Current efforts are focused on the synthesis of additional immunoproteasome-specific inhibitors that display specificity for each of the three catalytic subunits of the immunoproteasome.

Methods

Homology modeling

The suitable templates for modeling LMP2 and MECL1 have been identified through a BLAST search. SWISS-MODEL server was used to generate the homology model of the immunoproteasome subunits, based on the template and query sequence. The final model quality was evaluated using the Ramachandran plot (from PROCHECK) in SWISS-MODEL workspace.

Molecular Docking

After the homology models were built, the docking study was performed to explore the best possible modes of ligand binding with LMP2 (i.e. β1i) subunit of immunoproteasome and β5 subunit of constitutive proteasome using the Glide. Glide (Grid-Based Ligand Docking with Energetics) approximates a systematic search of positions, orientations, and conformations of the ligand in the receptor binding site using a series of hierarchical filters.34,38 The shape and properties of the receptor are represented on a grid by several different sets of fields that provide progressively more accurate scoring of the ligand pose.

To facilitate the definition of the center of the active site for docking, the crystal structure complex of regular proteasome with epoxomicin (PDB code: 1G65) was used, as neither the X-ray crystal structure of regular proteasome β5 subunit (PDB code: 1IRU-L) nor the homology modeled LMP2 subunit have a ligand bound in the active site. First, the two covalent bonds between Thr 1 and epoxomicin were broken and the missing atoms of epoxomicin were added. Then, the complex (1G65-KL) with waters removed was minimized in vacuum using Amber program (version 8) with all the residues fixed except the ligand in order to mimic the conformation of the ligand before reactions. After that, the minimized complex substructure 1G65-K was aligned to 1IRU-L and LMP2 by superimposing the backbone atoms in order to transfer the epoxomicin into 1IRU-L and LMP2 to get a reference ligand for docking. The RMSD values of the alignments for the 1IRU-L and LMP2 are 1.28 and 1.25 Å, respectively. After alignments, the coordinates of epoxomicin were transferred into 1IRU-LM and LMP2/MECL1. For the histidine residues, hydrogens were placed at the ε-position for His 35 in LMP2, His 66, His 97, and His 185 in MECL1; His 36 and His 58 in 1IRU-M; and at the δ-position for His 66, His 93, His 114, and His 116 in LMP2; His 38 in MECL1; His 10, His 178, and His 196 in 1IRU-L; His 77 and His 163 in 1IRU-M. Then, the two complexes (1IRU-LM and LMP2/MECL1 with epoxomicin in the active site) were minimized in vacuum with all the residues fixed except the ligand to get the best position of the ligand.

The proteins were imported into Maestro and prepared in the presence of ligand in the active site using Pprep in Glide. The grid midpoint was defined by the center of the bound epoxomicin. Geometries of both ligands were optimized at Hartree-Fock (HF) level with 6–31G* basis set using Gaussian program (03 version)37 and were docked with Glide in extra-precision mode with up to thirty poses saved per molecule. For each molecule, the best scoring pose was selected for the subsequent molecular dynamics simulations and binding free energy calculations.

Molecular dynamics

The general procedure for carrying out the MD simulations in water is similar to that used in our previously reported computational studies.39–44 Briefly, the MD simulations were performed using the Sander module of Amber (version 8) with Amber ff03 forcefiled.35 The partial atomic charges for the ligand atoms were calculated using the RESP protocol36 after electrostatic potential calculations at with the HF/6–31G* level using Gaussian (03 version).37 Each protein-ligand binding complex was neutralized by adding suitable counterions and was solvated in a truncated octahedron box of TIP3P water molecules45 with a minimum solute wall distance of 10 Å. The solvated systems were carefully equilibrated and fully energy-minimized. These systems were gradually heated from T = 10 K to T = 298.15 K in 60 ps before a production MD simulation run for 1 ns, making sure that we obtained a stable MD trajectory for each of the simulated systems. The time step used for the MD simulations was 2 fs. Periodic boundary conditions in the NPT ensemble at T = 298.15 K with Berendsen temperature coupling46 and P = 1 atm with isotropic molecule-based scaling36 were applied. The SHAKE algorithm47 was used to fix all covalent bonds containing hydrogen atoms. The non-bonded pair list was updated every 10 steps. The particle mesh Ewald (PME) method48 was used to treat long-range electrostatic interactions. A residue-based cutoff of 12 Å was utilized for the non-covalent interactions. The time-dependent geometric parameters were carefully examined to make sure that we obtained a stable MD trajectory for each simulated protein-ligand binding system. The coordinates of the simulated system were collected every 1 ps during the simulation. One hundred snapshots of the simulated structure within the stable MD trajectory were selected and minimized to perform the MM-PBSA calculations (see below).

Binding free energy calculations

The binding energies were calculated by using the molecular mechanics-Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) free energy calculation method.29 In the MM-PBSA method, the free energy of the protein-inhibitor binding, ΔGbind, is obtained from the difference between the free energies of the protein-ligand complex (Gcpx) and the unbound receptor/protein (Grec) and ligand (Glig) as following:

| (1) |

The binding free energy (ΔGbind) was evaluated as a sum of the changes in the molecular mechanical (MM) gas-phase binding energy (ΔEMM), solvation free energy (ΔGsolv), and entropic contribution (−TΔS):

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

The MM binding energies were calculated with the Sander module of the Amber (version 8). Electrostatic solvation free energy was calculated by the pbsa program of the Amber (version 8). The MSMS program49 was used to calculate the solvent accessible surface area (SASA) for the estimation of the non-polar solvation energy (ΔGnp) using Eq. 6 with the default parameters, i.e. γ = 0.00542 kcal/Å2 and β = 0.92 kcal/mol. The entropy contribution to the binding free energy (−TΔS) was obtained by using a local program developed in our own laboratory. In this method, the entropy contribution is attributed to two contributions: solvation free entropy and conformational free entropy. The detail of the method has been previously reported.50 The final binding free energy calculated for each protein-ligand binding mode was taken as the average of the ΔGbind values calculated for the 100 snapshots.

Most of the MD simulations were performed on an IBM X-series cluster with 340 nodes or 1,360 processors at University of Kentucky Center for Computational Sciences. The other computations were carried out on SGI Fuel workstations and a 34-processor IBM x335 Linux cluster in our own lab.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH (grants RC1MH088480 to Zhan and R01CA128903 to Kim) and by the Markey Cancer Foundation (Kim). Lei worked in Zhan’s laboratory for this project at the University of Kentucky as an exchange graduate student from Lanzhou University. The authors also acknowledge the Center for Computational Sciences (CCS) at University of Kentucky for supercomputing time on IBM X-series Cluster with 340 nodes or 1,360 processors.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Figure for Ramachandran plot generated for the LMP2 (A) and MECL1 (B) models; figure for the plots of RMSDs versus the simulation time in the MD-simulated complexes. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Mishto M, Bellavista E, Santoro A, Stolzing A, Ligorio C, Nacmias B, Spazzafumo L, Chiappelli M, Licastro F, Sorbi S, Pession A, Ohm T, Grune T, Franceschi C. Neurobiol. Aging. 2006;27:54. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diaz-Hernandez M, Hernandez F, Martin-Aparicio E, Gomez-Ramos P, Moran MA, Castano JG, Ferrer I, Avila J, Lucas JJ. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:11653. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-37-11653.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diaz-Hernandez M, Hernandez F, Valera AG, Ortega Z, Lucas JJ. J. Neurochem. 2007;102:100. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hideshima T, Chauhan D, Podar K, Schlossman RL, Richardson P, Anderson KC. Semin. Oncol. 2001;28:607. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hideshima T, Anderson KC. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2002;2:927. doi: 10.1038/nrc952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wehenkel M, Hong JT, Kim KB. Molecular Biosystems. 2008;4:280. doi: 10.1039/b716221a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yewdell JW. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:9089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504018102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borissenko L, Groll M. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:687. doi: 10.1021/cr0502504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marques AJ, Palanimurugan R, Matias AC, Ramos PC, Dohmen RJ. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:1509. doi: 10.1021/cr8004857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuhn DJ, Hunsucker SA, Chen Q, Voorhees PM, Orlowski M, Orlowski RZ. Blood. 2009;113:4667. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-171637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abby H, Kedra C, Kyung-Bo K. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005;2005:4829. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho YK, Bargagna-Mohan P, Wehenkel M, Mohan R, Kim KB. Chem. Biol. 2007;14:419. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuhn DJ, Voorhees PM, Chen Q, Strader JS, Bruzzese F, Ciavarri JP, Hu ZG, Orlowski RZ. Blood. 2006;108:3458. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muchamuel T, Basler M, Aujay MA, Suzuki E, Kalim KW, Lauer C, Sylvain C, Ring ER, Shields J, Jiang J, Shwonek P, Parlati F, Demo SD, Bennett MK, Kirk CJ, Groettrup M. Nat. Med. 2009;15:781. doi: 10.1038/nm.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orlowski RZ, Kuhn DJ, Small GW, Michaud C, Orlowski M. Blood. 2005;106:248. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parlati F, Aujay M, Bedringaas SL, Demo S, Gjertsen B, Goldstein E, Jiang J, Kirk C, Laidig G, Lorens J, Lu Y, Micklem D, Ruurs P, Shenk K, Sylvain C, Sun C, Woo T, Zhou HJ, Bennett M. Blood. 2007;110:1599. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parlati F, Aujay MA, Demo SD, Goldstein ED, Jiang J, Kirk CJ, Laidig GJ, Lu Y, Muchamuel T, Shenk KD, Sylvain C, Sun CM, Woo TM, Zhou HJ, Bennett MK, McDonagh KT. Blood. 2006;108:4392. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roccaro AM, Sacco A, Aujay M, Ngo HT, Azab AK, Azab F, Quang P, Maiso P, Runnels J, Anderson KC, Demo S, Ghobrial IM. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-243402. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou H-J, Aujay MA, Bennett MK, Dajee M, Demo SD, Fang Y, Ho MN, Jiang J, Kirk CJ, Laidig GJ, Lewis ER, Lu Y, Muchamuel T, Parlati F, Ring E, Shenk KD, Shields J, Shwonek PJ, Stanton T, Sun CM, Sylvain C, Woo TM, Yang J. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:3028. doi: 10.1021/jm801329v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myung J, Kim KB, Crews CM. Med. Res. Rev. 2001;21:245. doi: 10.1002/med.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groll M, Heinemeyer W, Jager S, Ullrich T, Bochtler M, Wolf DH, Huber R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:10976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.10976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kloetzel PM. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:179. doi: 10.1038/35056572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wehenkel M, Ho YK, Kim K-B. Proteasome Inhibitors: Rencent progress and future directions. Modulation of Protein Stability in Cancer Therapy. 2009:99. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unno M, Mizushima T, Morimoto Y, Tomisugi Y, Tanaka K, Yasuoka N, Tsukihara T. Structure. 2002;10:609. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00748-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groll M, Ditzel L, Lowe J, Stock D, Bochtler M, Bartunik HD, Huber R. Nature. 1997;386:463. doi: 10.1038/386463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Momose I, Umezawa Y, Hirosawa S, Iinuma H, Ikeda D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:1867. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Groll M, Kim KB, Kairies N, Huber R, Crews CM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:1237. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kollman PA, Massova I, Reyes C, Kuhn B, Huo SH, Chong L, Lee M, Lee T, Duan Y, Wang W, Donini O, Cieplak P, Srinivasan J, Case DA, Cheatham TE. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:889. doi: 10.1021/ar000033j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Apweiler R, Martin MJ, O'Donovan C, Magrane M, Alam-Faruque Y, Antunes R, Barrell D, Bely B, Bingley M, Binns D, Bower L, Browne P, Chan WM, Dimmer E, Eberhardt R, Fedotov A, Foulger R, Garavelli J, Huntley R, Jacobsen J, Kleen M, Laiho K, Leinonen R, Legge D, Lin Q, Liu WD, Luo J, Orchard S, Patient S, Poggioli D, Pruess M, Corbett M, di Martino G, Donnelly M, van Rensburg P, Bairoch A, Bougueleret L, Xenarios I, Altairac S, Auchincloss A, Argoud-Puy G, Axelsen K, Baratin D, Blatter MC, Boeckmann B, Bolleman J, Bollondi L, Boutet E, Quintaje SB, Breuza L, Bridge A, deCastro E, Ciapina L, Coral D, Coudert E, Cusin I, Delbard G, Doche M, Dornevil D, Roggli PD, Duvaud S, Estreicher A, Famiglietti L, Feuermann M, Gehant S, Farriol-Mathis N, Ferro S, Gasteiger E, Gateau A, Gerritsen V, Gos A, Gruaz-Gumowski N, Hinz U, Hulo C, Hulo N, James J, Jimenez S, Jungo F, Kappler T, Keller G, Lachaize C, Lane-Guermonprez L, Langendijk-Genevaux P, Lara V, Lemercier P, Lieberherr D, Lima TD, Mangold V, Martin X, Masson P, Moinat M, Morgat A, Mottaz A, Paesano S, Pedruzzi I, Pilbout S, Pillet V, Poux S, Pozzato M, Redaschi N, Rivoire C, Roechert B, Schneider M, Sigrist C, Sonesson K, Staehli S, Stanley E, Stutz A, Sundaram S, Tognolli M, Verbregue L, Veuthey AL, Yip LN, Zuletta L, Wu C, Arighi C, Arminski L, Barker W, Chen CM, Chen YX, Hu ZZ, Huang HZ, Mazumder R, McGarvey P, Natale DA, Nchoutmboube J, Petrova N, Subramanian N, Suzek BE, Ugochukwu U, Vasudevan S, Vinayaka CR, Yeh LS, Zhang J. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:D142. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melo F, Feytmans E. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;277:1141. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laskowski RA, Macarthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993;26:283. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friesner RA, Banks JL, Murphy RB, Halgren TA, Klicic JJ, Mainz DT, Repasky MP, Knoll EH, Shelley M, Perry JK, Shaw DE, Francis P, Shenkin PS. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:1739. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Case DA, Darden TA, Cheatham ITE, Simmerling CL, Wang J, Duke RE, Luo R, Merz KM, Wang B, Pearlman DA, Crowley M, Brozell S, Tsui V, Gohlke H, Mongan J, Hornak V, Cui G, Beroza P, Schafmeister C, Caldwell JW, Ross WS, Kollman PA. San Francisco: University of California; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bayly CI, Cieplak P, Cornell WD, Kollman PA. J. Phys. Chem. 1993;97:10269. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JJA, Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Strain MC, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JVCQ, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. Pittsburgh, PA: Gaussian, Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friesner RA, Murphy RB, Repasky MP, Frye LL, Greenwood JR, Halgren TA, Sanschagrin PC, Mainz DT. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:6177. doi: 10.1021/jm051256o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.AbdulHameed MDM, Hamza A, Zhan CG. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:26365. doi: 10.1021/jp065207e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamza A, Cho H, Tai HH, Zhan CG. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:4776. doi: 10.1021/jp0447136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamza A, Tong M, AbdulHameed MDM, Liu JJ, Goren AC, Tai HH, Zhan CG. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 114:5605. doi: 10.1021/jp100668y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu JJ, Zhang YK, Zhan CG. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2009;113:16226. doi: 10.1021/jp9055335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang XQ, Gu HH, Zhan CG. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2009;113:15057. doi: 10.1021/jp900963n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu JJ, Hamza A, Zhan CG. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009;131:11964. doi: 10.1021/ja903990p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, Vangunsteren WF, Dinola A, Haak JR. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:3684. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. J. Comput. Phys. 1977;23:327. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Essmann U, Perera L, Berkowitz ML, Darden T, Lee H, Pedersen LG. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:8577. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanner MF, Olson AJ, Spehner JC. Biopolymers. 1996;38:305. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199603)38:3%3C305::AID-BIP4%3E3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pan YM, Gao DQ, Zhan CG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5140. doi: 10.1021/ja077972s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 0.99rc6. Schrödinger, LLC; http://www.pymol.org. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.