The prevalence of morphea in childhood is not well established, but past reports suggest approximately 2/3 of linear morphea begins before age 18, and 20–30% of morphea overall begins in childhood.1, 2 Studies have described significant morbidity in children with morphea, but none have addressed the disease effects when they reach adulthood. From the Morphea Registry and DNA Repository at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW), we identified adults with pediatric onset morphea (APOM) 18yr or older to address the impact of childhood morphea in adults.

METHODS

Patients were enrolled between September, 2007 and November, 2009 and all were examined by author (HJ). Disease-related quality of life (QOL) was measured with the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). Symptoms of itch, pain, and numbness are assessed on visual analogue scale (VAS). Data on disease progression, activity and inactivity were collected. Presence of concomitant disorders, symptoms and permanent sequelae are confirmed via physical examination by authors or extraction from medical records. Each patient was assigned a deep modifier, if present.

ANA determined using published protocols, positive ANA (≥ 1:80) were tested for antibodies to extractable nuclear antigens, topoisomerase, and RNA polymerase.

RESULTS

27/200 patients met enrollment criteria. The mean age of onset was 11.5yr (range 3–17yr, median 13) current mean age 30.6yr (range 18–78yr, median 26). 20/27 patients had linear morphea (74%) (including ECDS (n=7) or PHA (n=2)). Generalized morphea: 18.5%, plaque 7.4%. 7/27 (26%) had at least one autoimmune disease. 13/27 had family history of autoimmune disease. Overall, 78% 21/27 had noncutaneous symptoms, musculoskeletal complaints (67%, n=18), neurologic manifestations (44%, n=12) and Raynaud’s-like phenomena (25%, n=7). Physical exam: 56% (15/27) had permanent sequelae (limited range of motion 11/15; deep atrophy 6/15; limb length discrepancy 1/15; joint contracture 2/15). All occurred in linear morphea (15/20). 81% (21/27) had ≥1 symptom related to their morphea (pain, itch, numbness).

Mean DLQI score was 3.5 (median 2, range 0–12). 6/27 (22%) of scores indicated moderate-very large effect QOL. Patients with moderate-very large effect had a greater mean number of lesions (mean=8 vs 5 low-no effect, p>0.05). Limited range of motion was significantly associated with a lower disease-related quality of life (r=39, p=0.05), positive ANA; 37% (10/27) speckled pattern). Antibodies against nonchromatin protein antigens associated with speckled pattern were not found.

All patients received treatment, topical corticosteroids (13/27), Methotrexate (8/20 linear patients); Systemic corticosteroids (6/20 linear patients, 1 generalized patient). Physical therapy (3/20 linear patients).

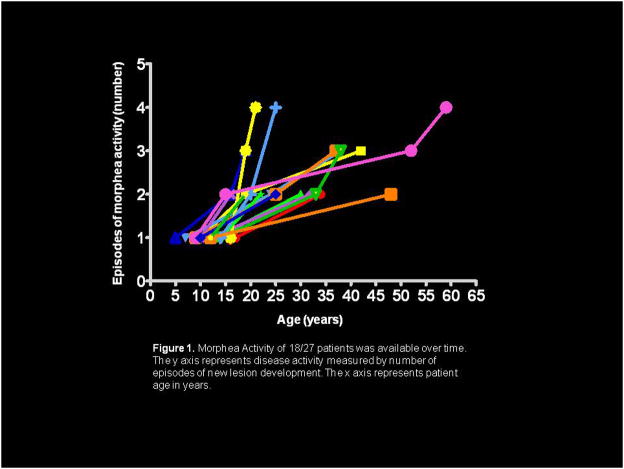

89% (24/27) developed new or expanded lesions over time. Seven (29%) reported inciting event (trauma, cessation/taper of systemic therapy, pregnancy). Time to recurrence from initial disease onset ranged from 6–18 years. Sixteen described periods of remission and exacerbation, while 8 described continuous activity of existing lesions or formation of new lesions. Overall, with increasing age, there were increasing numbers or expansion of lesions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Morphea Activity of 18/27 patients was available over time. The y axis represents disease activity measured by number of episodes of new lesion development. The x axis represents patient age in years.

COMMENT

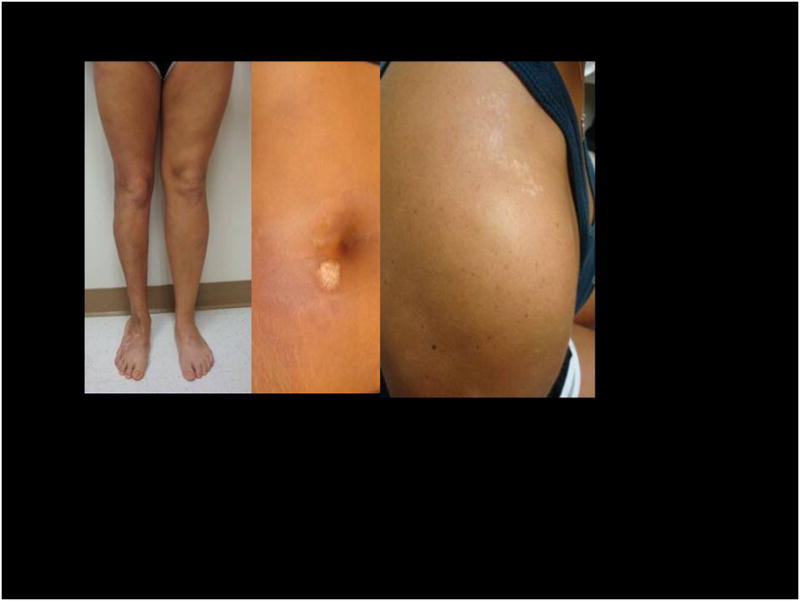

This study represents the first examination of APOM from inception of the UTSW Morphea Registry and DNA Repository. The predominant morphea subtype in our group was linear, reflecting the predominance of this subtype in children.3, 4 Patients maintained this subtype into adulthood but developed more lesions (Figure 2). Generalized patients had plaque subtype at disease onset that progressed to meet criteria for generalized disease over time. This underscores the progressive nature of morphea.

Figure 2.

This photo demonstrates the chronic nature of morphea, as well as permanent sequelae. Initial lesions began on the right leg at age 5yr, second on abdomen at age 16yr, and third on right shoulder at age 19. Note muscle atrophy, limb length discrepancy and pes planus foot deformity.

APOM have an autoimmune phenotype. Prior studies demonstrated adult morphea patients have increased prevalence of autoimmunity compared with the general population.3, 5 Children with morphea had increased prevalence of familial autoimmunity, but relatively less risk of personal autoimmune disease. An unanswered question was whether children with morphea have increased autoimmunity as adults. Our study suggests APOM develop autoimmune disorders in adulthood, reaching 26% (7/27) patients (5/7 as adults). This is similar to reported rates for adults and greater than childhood rates.

APOM have negative impact on QOL, especially if they have functional impairment (p≤0.05) and with greater lesion number. Further, permanent functional impairment, persistent disease activity, extracutaneous symptoms were all present in the majority of patients. This data underscores the progressive, disabling course of APOM. Predominance of topical therapy in this group implies undertreatment, possibly impacting long term outcome. Even in those treated with immunosuppresives, 2/7 flared on withdraw/cessation. Systemic treatment may inhibit disease activity, but does not preclude subsequent disease reactivation.

In contrast to prior studies, 89% of our cohort had continued disease activity. Because of referral bias, prospective cohort studies are needed to determine accurate prevalence. Nonetheless, our data indicates there is a subset with active disease in adulthood who need life-long evaluation and repeated courses of aggressive treatment to prevent the significant morbidity noted in our group.

Parents of children with morphea should be counseled on possibility of recurrence, vigilance in identifying new activity, and to seek treatment upon reactivation.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr(s) Saxton-Daniels and Jacobe had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Dr(s) Saxton-Daniels and Jacobe. Acquisition of data: Dr(s) Saxton-Daniels and Jacobe. Drafting of the manuscript: Dr(s) Saxton-Daniels and Jacobe. Critical Revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Dr(s) Bergstresser, Jacobe and Saxton-Daniels. Statistical Analysis: Dr(s) Bernstein, Jacobe and Saxton-Daniels. Obtained funding: none. Administrative, technical, or material support: Dr(s) Saxton-Daniels and Jacobe. Study Supervision: Dr. Jacobe. This study was supported in part by the Dermatology Foundation Clinical Development Award in Medical Dermatology and NIH/NIAMS K23 Award (Dr. Jacobe). The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Financial Disclosure: None reported. We are indebted to Dr. Paul R. Bergstresser, Dr. Ira Bernstein, UTSW Medical Center, and Dr. Frank Arnett, UT Houston Medical Science Center.

Contributor Information

Stephanie Saxton-Daniels, Email: Stephanie.Saxton@utsouthwestern.edu, Department of Dermatology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Heidi T. Jacobe, Email: Heidi.Jacobe@utsouthwestern.edu, Department of Dermatology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

References

- 1.Peterson LS, Nelson AM, Su WP, Mason T, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. The epidemiology of morphea (localized scleroderma) in Olmsted County 1960–1993. J Rheumatol. 1997 January;24(1):73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vierra E, Cunningham BB. Morphea and localized scleroderma in children. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1999 September;18(3):210–25. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(99)80019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, et al. Juvenile localized scleroderma: clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. An international study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006 May;45(5):614–20. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christen-Zaech S, Hakim MD, Afsar FS, Paller AS. Pediatric morphea (localized scleroderma): review of 136 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 September;59(3):385–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leitenberger JJ, Cayce RL, Haley RW, Adams-Huet B, Bergstresser PR, Jacobe HT. Distinct autoimmune syndromes in morphea: a review of 245 adult and pediatric cases. Arch Dermatol. 2009 May;145(5):545–50. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]