Abstract

Depression among Mexican immigrant women and children exceeds national prevalence rates. Given the influence of maternal depression on children, a clinical trial testing the effects of the Mexican American Problem Solving (MAPS) program was designed to address depression symptoms of Mexican immigrant women and their fourth and fifth grade children (302 dyads) through a linked home visiting and after school program compared to peers in a control group. Schools were randomized to intervention and control groups. There were statistically significant improvements in the children’s health conceptions and family problem solving communication, factors predictive of mental health. Improvements in children’s depression symptoms in the intervention group approached statistical significance. These promising results suggest that refined school based nursing interventions be included in community strategies to address the serious mental health problems that Mexican immigrants face.

Keywords: Mexican American, Mother Child depression, Problem-solving, Intervention, Clinical Trial

Introduction

Mexican immigrant women and their children experience depressive symptoms at rates much higher than other ethnic groups in the United States. While the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) estimates that 10% of adult and child populations experience depression, estimates for women of Mexican descent range from 20% - 64% and rates for Hispanic children range from 31 - 47.5% (Cowell, Gross, McNaughton, Ailey & Fogg, 2005; Grunbaum, et al, 2004). The terms “Mexican” and “Hispanic” are the terms used by authors. Factors associated with mental health risk in the Mexican immigrant community are often related to stresses such as poverty, low education levels and related limited opportunities for employment, neighborhood stress, and need for language acquisition (Cueller, & Roberts, 1997; Codina & Montalvo, 1994; Finch, Kolody & Vega, 2000, Heilemann, Lee & Kury, 2002; Hovey, 2000; Munet-Vilaro, Folkman & Gregorich, 1999; Salgado de Snyder, Cervantes & Padilla, 1990).

The purpose of this paper is to report the effectiveness of the Mexican American Problem Solving (MAPS) program, a clinical trial testing a theoretically based intervention. MAPS was a cognitively based problem solving program delivered on linked home visits to mothers and after school program classes to children. MAPS was designed to reduce depressive symptoms for Mexican immigrant mothers and their fourth and fifth grade children by increasing problem solving skills practiced in the intervention.

Decades of research on the relationship between maternal and child mental health have shown harmful effects of maternal depression on children. High rates of depressive symptoms in Mexican American children are linked with maternal stress and depression, economic stress, conflict between parents, and inconsistent parenting (Barrera, et al 2002; Deardorff, Gonzales and Sandler, 2003; Gonzalez, Pitts, Hill and Roosa, 2000; Roberts, Roberts & Chen, 1998; Masi & Cooper, 2006; McNaughton, Cowell, Gross, Fogg & Ailey, 2004). The link between parental and child depression is evident in studies that have focused on parenting and environmental characteristics including poor communities. In 1990, Downey and Coyne reported an extensive review of literature showing the issues linking parental and child depression including the fact that child depression symptoms may be a reflection of psychological distress or a recurrent, serious illness. Additionally, the review highlighted that children of depressed parents were at higher risk for adjustment problems and depression than children of parents without depression. Conversely, as parent depression symptoms decreased, child adjustment improved.

Childhood mental health is reflected in school behaviors including internalizing behaviors such as lack of concentration that distracts children as reflected in their personal work habits and externalizing behaviors such as social interactions including aggression or withdrawal (Dennis, Parke, Coltrane, Blacher & Borthwick-Duffy, 2003; Goodman & Gotlib, 2002).

Social stresses of lower socioeconomic status and low education levels are consistently reported as associated with depressive symptoms for Mexican American families. Forty percent of Latino children in the US live in poverty (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000), an estimate that is twice as high as the US average for all children and four times higher than the poverty rate of non-Latino white children. It is common for Latino immigrants to arrive in the US with less than a high school education, which further limits their opportunity to advance their economic condition (US Census Bureau, 2007).

Our pilot work in the Chicago community assessed mental health risk for Mexican immigrant mothers and their 4th-5th grade children and found 67% (n=18) of mothers and 59% (n=44) of their children reported depressive symptoms above the cut-point for referral. In subsequent focus groups with Mexican immigrant mothers, they described multiple challenges adjusting to life in the United States, and described their children’s schools as a preferred location to receive supportive services (Cowell, McNaughton & Ailey, 2000).

To date, there are no evidence based mother-child problem solving programs specifically designed for Mexican immigrants with school aged children (US Department of Health and Human Services, nd). In a review of 21 parenting interventions adapted for Latino families, Dumka, Lopez, and Carter (2004) reported that 6 of the 21 parenting intervention studies included children aged 9 to 11. The parenting intervention programs focused on cardiovascular health, prevention of drug use, family therapy for troubled children, and supporting children’s education efforts. The authors noted that interventions are needed that focus on enhancing parent-child relationships.

Conceptual Framework

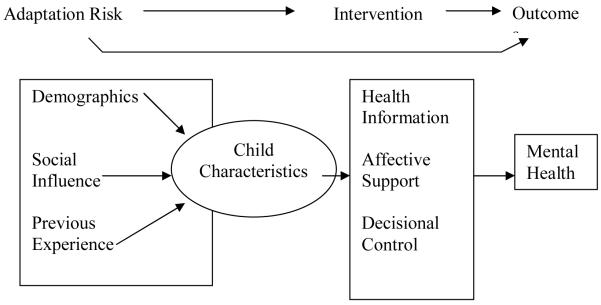

The Mexican American Problem Solving (MAPS) Model represents an adaptation of the Interaction Model of Client Health Behavior (Cox, 2003) and is presented in Figure 1. The MAPS model was based on the literature review as well as earlier pilot work (Cowell, McNaughton, & Ailey, 2000). The MAPS model consists of three elements including Adaptation Risk, Intervention and Outcomes. The Adaptation Risk element consists of background variables including demographic, social influence (acculturation, family functioning and family resilience) and previous experiences (mother and child stress) that impact mental health as well as the child personal characteristics that include health conceptions and self-esteem. Background variables can directly influence child outcomes. The demographic and previous experience variables are less amenable to change compared to social influence and child personal characteristics of health conceptions and self-esteem. The child personal characteristics influence the child outcomes such as mental health and school behavior directly. The intervention consists of health information (in this case the problem solving information and practice), affective support (addressing relevant problems) and decisional control (recognizing families’ scheduling demands, preferred place for intervention and participation rates). The problem solving information is applied to problems that were identified by community partners in pilot work. Further the problem solving information is tailored to current needs of participants to enhance relevancy. The outcome variables targeted by the intervention support mental health and include family problem solving communication, mothers’ depression symptoms, child depression symptoms and school performance. The children’s personal characteristics are also targeted because of the close association with child mental health.

Figure 1.

Mexican American Problem Solving Model (MAPS Model)

Methods

Design

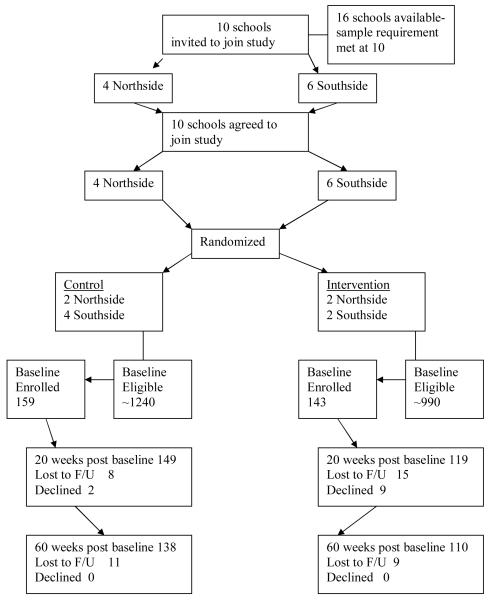

The design was a randomized clinical trial. Elementary schools in Chicago with enrollments of 30% or more Latinos were selected and randomly assigned to intervention or control conditions. Prior to launching the study, a pool of 16 schools was identified as eligible for the study however the targeted sample size was reached at 10 schools. Randomization took place at the school level to eliminate the intervention contamination across participants within schools. The study was managed by targeting six waves of 50 mother child dyads (25 intervention and 25 control) launched at the beginning of school semesters (September and January) and was carried out over three years. The Rush University Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved all research procedures.

Setting

North and south side Chicago neighborhoods were the setting for the study. Racial and ethnic diversity for the two neighborhoods were different. North side school administrators reported that there were more than 60 languages spoken as primary language other than English yet over 40% of students speaking English as a second language, spoke Spanish. On the south side, 98% of residents identified themselves as Hispanic, and Spanish was the only language offered in bilingual classes in the schools (Illinois School Report Card, 1999). Knowing that there were demographic differences in the neighborhood, schools were matched by neighborhood then selected for intervention or control.

Recruitment

Power analyses indicated that a sample of 220 (110 in both groups) was adequate for a clinical trial (power=.84, effect size of .40 and alpha of .05) based on an effect size of .74 obtained in pilot work (Cowell, McNaughton & Ailey, 2000). Three hundred and two mother-child dyads were recruited based on an anticipated drop out rate of 27% reported in six model home visiting randomized clinical trials ranging from 20-67% (Gomby, Culross, & Behrman 1999).

School administrators or their designated coordinator recruited eligible mothers and children by presenting the information about MAPS to groups of parents, or individuals of Mexican origin. The MAPS program was presented as a school nursing program designed to help Mexican immigrant women and their children adjust to life in the USA through problem solving. School coordinators distributed a simple recruitment flyer and interested parents were encouraged to return the signed flyer. The researchers contacted mothers who had returned signed flyers expressing interest in the MAPS program. Only mothers born in Mexico were eligible. If there was more than one child in 4th or 5th grade, the mother could choose only one child to participate in the study. The school coordinators reported that mothers usually chose a child with greater problems. Children in self-contained, special education class rooms were not eligible. At the final assessment (60 weeks post baseline), 110 or 77% of the intervention dyads and 138 or 87% of the control dyads were retained (total sample retained 248 or 82% at 60 weeks post baseline). The intervention sample represented 14.5% of the fourth and fifth grade population at the study schools and the control sample represented 12.8% of the fourth and fifth grade population at the control schools. See Consort Flow Diagram in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Consort Flow Diagram

Sample

Mothers’ mean age was 35.9 years. Most mothers were married or partnered and 73% of them did not have more than a middle school education. Mothers were in the United States for an average of 13 years. Over 80% of mothers reported incomes of less than $26,000 per year. Mothers reported their originating home state in Mexico. Approximately 50% of participants originated from rural states in Mexico. See Table 1 for sample characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Sample N=302

| Characteristic | Mean/percentage | Range | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother age | 35.9 years | 23-65 years | 6.7 |

| Child age | 10.4 years | 0.78 | |

| Income | <$26,000/year 80.1% |

||

| Mother education | <6th grade 47.7% |

||

| Years in USA | 12.9 years | 7.7 | |

| Age on arrival in USA |

22.3 years | 7.3 | |

| Married/partnered | 81.1% |

Procedures

A bilingual, bicultural project assistant was available at a toll free number to facilitate positive relations with schools and participants. Trained bilingual social workers collected data on home visits or at a location convenient for the mother at baseline, 20 and 60 weeks after baseline. Incentives for the data collection were $30, $20 and $50 respectively for each of the data collection visits. Children received a small gift at each data collection visit such as markers, books and water bottles. Data collectors secured informed consent from mothers and assent from children at the initial data collection (Cowell, Gross, McNaughton, Ailey & Fogg, 2005). All research instruments were read to or with mothers and children in the language of their choosing to control for differences in literacy levels. Most of the mothers preferred being interviewed in Spanish while the majority of children preferred English. Mothers and children with depression scores at the cut point for depression or suicidal ideation were referred for mental health assessment. Referral procedures consisted of a telephone call from our bilingual project assistant who read a standardized script stating our concern over the possibility that mothers and/or their children were feeling down or sad with encouragement to visit a low cost or free mental health professional in their communities.

Measures

The translation procedures, linguistic and cultural review of the measures are reported in detail elsewhere (McNaughton, Cowell, Gross, Fogg and Ailey, 2004).

Adaptation Risk Measures

Acculturation was assessed by the Acculturation and Structural Assimilation Scale (ASAS) which includes five subscales of acculturation and two subscales of structural assimilation. For this study five subscales were used including adult proficiency in English (3 items), adult patterns of English usage (10 items), value placed on Mexican heritage (3 items), attitude toward traditional family structure (7 items), and adult interaction with mainstream society (3 items). Higher scores indicate greater assimilation into mainstream American culture. Hazuda, Stern, and Haffner (1988) reported the construct validity of the instrument. For this study, the Cronbach Alpha coefficient was 0.86.

Family functioning was assessed by the Feetham Family Functioning Survey (FFFS; Roberts & Feetham, 1982), a 29 item instrument. Three primary family functioning areas are assessed including family relationships within the family and its subsystems, division of labor and reciprocal relationships within the family and each individual family member. To address marital differences including married and partnered relationships as well as single parent in families, a statement was inserted in each of the items addressing spousal relationships in family functioning (items 3, 4, 7, 14, 18, 21, 23, 24, and 25). The statement was…The term spouse refers to your husband or the person who assumes the functions of a spouse. If you do not a have person in the spouse role, answer the questions based on how much you want the functions met. The Porter format (Porter, 1962, 1963a, 1963b) is used as the response set. The Porter format captures the perceived magnitude, importance and degree of need satisfaction for each item. A discrepancy score is calculated by subtracting the degree of need from the magnitude to indicate satisfaction with the function represented in the item. High discrepancy scores indicate poorer family functioning. The importance score reports the individual’s value on an item and identifies areas of perceived need. The validity of the FFFS with Mexican immigrant women was established in the pilot work (Cowell et al, 2000) by a nominated group method indicating high discrepancy scores among mothers known to be in dysfunctional families. Cronbach alpha coefficient in this study for the FFFS with the spousal definition spelled out was 0.86.

Family resilience was assessed by the Family Hardiness Index (FHI; McCubbin, McCubbin, & Thompson, 1986). Family hardiness assesses the internal strengths and durability of the family and is characterized by reported sense of control over life events. The FHI is a 20-item scale with three subscales representing commitment, challenge, and control. The items responses (0-3) are summed with higher scores representing greater family hardiness. McCubbin and colleagues (1986) reported the validity of the FHI by showing positive and statistically significant correlation coefficients with FHI scores and indicators of family strength including family flexibility (FACES II), Family, Time and Routines, and Quality of Life. The Cronbach Alpha Coefficient for this study was 0.78.

Maternal stress was assessed by the adapted Everyday Stress Index (ESI; Hall, 1990) that included additional items measuring stress associated with child rearing (Adams-Wheeler & Gross, 1997). The ESI measures parental report of stress related to financial concerns, employment problems, parenting concerns, family responsibilities and interpersonal conflicts. The 10 additional items include the stress related to time away from children, child safety and well-being, bad influence of other children and demands of children on mothers. Items are scored 1-4 with higher scores indicating greater stress. The validity of the ESI (20 items) is reflected in the statistically significant associations with maternal depression, parenting self-efficacy and child behavior (Gross, Sambrook, & Fogg, 1999); Hall, 1990). Validity of the adapted ESI (30 total items) with Mexican immigrant women is reflected in the statistically significant association with their depression scores, r = 0.45 (McNaughton, Cowell, Gross, Fogg & Ailey, 2004). The Cronbach Alpha coefficient of the adapted ESI in this study was 0.90.

Child stress was assessed by the Child Stress Index (CSI; Attar, Guerra, & Tolan, 1994). The CSI contains 16 items that assess the Circumscribed Events (death of a close family member or friend, hospitalization of a family member, destruction of personal property due to disaster or theft), Life Transitions (marriage in the family, arrival of a new baby, change in school or residence), and Exposure to Violence (need to hide from shootings, need to stay indoors because of gang threat or drugs in the neighborhood). Two CSI violence and death related items were not included because of redundancy. Items are rated 0-1 (no or yes to the experience) and items are summed for a total score that can range from 0 – 14. Attar and colleagues (1994) reported construct validity for the measure.

Measures of child personal characteristics were the Child Health Self Concept (CHSC) for health conceptions and Global Self-Worth for self esteem. Both health conceptions and self-esteem are predictive of healthy adaptation including child mental health (Garber & Martin, 2002). The CHSC is a self-report instrument assessing health conceptions and beliefs and is rated by children (Hester, 1984). There are five subscales comprising the CHSC. Conceptions related to 1) Family relations, 2) Emotional health, 3) General health, 4) Sleep, and 5) Friendships. Scoring is summative on the 45-item scale with a score of 1 representing a negative health self-concept and a score of 4 representing a positive health self-concept on an item. Total scores can range from 45 to 180. The Cronbach Alpha coefficient for the CHSC in this study was 0.87. The GSW is a 6-item subscale of the Self-Perception Profile (Harter, 1982). The correlation coefficient of the GSW total score and the summed self-esteem items of the CDI (items 2, 7, 9, 14 and 25 was (r = .69) indicating the validity of the measure with Mexican American children. The Cronbach Alpha coefficient for the GSW in this study was 0.62.

MAPS Outcome Measures

Family Problem Solving Communication is a measure of problem solving and coping in families experiencing stress (FPSC; McCubbin, McCubbin, & Thompson, 1988). Coping strategies and problem solving communication patterns are viewed as generalized ways of responding to hardship and difficulties within families. Family communication is viewed as the measure of how families manage tension and strain and derive satisfaction. The FPSC scale is a 10-item instrument with a four-point Likert scale response. Respondents rate their agreement with items about their family communication. The instrument evaluates two, 5-item subscales showing incendiary or affirming communication. The FPSC was available in Spanish and expert Hispanic reviewers were in 99% agreement on the content validity of the translated items (Cowell, Gross, McNaughton, Ailey & Fogg, 2005). The Cronbach Alpha coefficient for the FPSC scale was 0.82.

Mothers’ mental health was assessed by the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSC; Derogatis, Lipman, Rickels, Uhlenhuth, & Covi, 1974), a 25 item, self-rated measure consisting of two subscales, anxiety and depression. Item scores, 1-4, are summed, then divided by the number of items answered yielding a possible total score of 1 to 4. Scores of 1.75 or greater indicate a greater risk and individuals reporting scores of 1.75 or greater are referred for further evaluation. The validity of the HSC with Mexican immigrant women was demonstrated through statistically significant correlation with theoretically hypothesized variables of family functioning and child depression (Cowell et al, 2000). The Cronbach Alpha coefficient was 0.94.

Children’s depression was assessed by the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992). The CDI is a 27 item, self-report survey based on the Beck Depression Inventory (Kovacs, 1985). The CDI was designed for use among 8 to 13 year old children (Saylor, Finch, Spirito, & Bennett, 1984). Item scores range from 0 (indicating symptom is not present) to 2 (more severe experience of the symptom). Total scores can range from 0 to 54 with higher scores indicating more symptoms of depression. The cutoff score for this study was 12 as recommended by Kovacs among clinical populations (1992), since the Mexican American children were at heightened risk. The validity of the CDI among Mexican American children is reflected in the strong correlation between theoretically associated variables including health conceptions (r = − 0.65) and self-esteem (r = −0.47). The Cronbach Alpha was 0.82.

A variety of school behaviors are considered indicative of children’s mental health (Dennis, Parke, Coltrane, Blacher & Borthwick-Duffy, 2003; Murray, Low, Hollis, Cross & Davis, 2007). While attendance and tardiness are common indicators, our participating children had high rates of attendance (over 95%) and little tardiness. We used teachers’ reports of social habits and work habits from the report card with a check mark indicating a need for improvement and given a score of one. The social habits included were self-control, appropriate decision making, respects others, respects property and courtesy with scores ranging from 0-5. The work habits were prepared to work, follows directions, independent/group work, cares for materials, completes classroom assignments and completes homework assignments with scores ranging from 0-6.

Intervention

The manual guided intervention tested in this clinical trial was a linked home visiting intervention delivered by nurses to mothers and small group classes to children. The intervention focused on simplified problem solving steps, STOP, THINK and ACT applied to relevant topics that are presented in Table 2. The nurses were educated with a minimum of a BSN degree. Content of the intervention, delivery method (home visits), and the decision to collaborate with schools in delivering the program were informed by focus groups with Mexican immigrant mothers (Cowell, et al, 2000). Mothers were offered 10 home visits at a time and place of their choosing. Mothers in both neighborhoods received a mean of 6 home visits lasting approximately 75 minutes each. Nurses followed an established protocol that followed problem solving steps (Stop, Think, and Act) as applied to the problems women identified in focus groups. However, nurses were also instructed to focus on problems that mothers were most immediately concerned about, and to assist mothers in applying the problem solving steps to those problems. Nurses had freedom to apply the appropriate module content of the home visiting manual to the most pressing needs of the mothers. The mothers almost universally, preferred to receive the intervention in Spanish. Mothers received on average 6 (SD 3.72) home visits representing 6.3 (SD 4.2) hours of intervention. There were no statistically different intensity rates for mothers in either of the neighborhoods.

Table 2.

Intervention Topics

| Children’s classes | Mothers’ home visits |

|---|---|

|

|

The home visiting intervention fidelity was assessed several ways. The project manager communicated with the nurses every 1-2 weeks or more frequently if the nurse requested. Nurses submitted self-reported check lists on each home visit, verifying application of the STOP, THINK and ACT steps. Finally, all home visits were tape recorded and 20 percent of the tapes were randomly selected and evaluated for fidelity.

The children’s linked intervention complemented the mother’s program and used the same STOP, THINK and ACT steps. Children participated in small group discussions (4-5 children per group) before or after school. Children’s groups were conducted in the elementary school by bilingual nurses and followed a manual including group and individual problem solving activities as well as provision of basic health promotion activities. Children preferred to have the classes in English. Children were scheduled to receive 10 classes each and received on average, 6.36 classes. Children in the north side neighborhood received an average of eight classes and children on the south side neighborhood received an average of 4.72 classes (t = −2.47, df = 109, p = 0.02). Intervention fidelity was assessed for the children’s classes by frequent contact (every 1-2 weeks or as needed) with the nurses by the project manager and the use of the self report check list verifying the delivery of the scripted classes applying the STOP, THINK and ACT steps.

The correspondence of the mothers’ and children’s linked intervention is reflected in the mothers’ visit centered on Growing up in Mexico/ living in the United States and the children’s class, A Sense of Self. The nurse uses open ended questions guiding the mother to describe a childhood in Mexico. Selected questions include how is childhood different in Mexico than in the United States? What is expected of children in Mexico, how should children behave and is this different than the way children are expected to behave in the United States? The mother would work with the nurse to apply the STOP, THINK and ACT steps to evaluate problems identified in the exercise. The children’s class focused on how mentors, role models and ancestors influence who they are. Selected questions guided them to identify influential people in their lives. Finally, children described what they liked about being Mexican and any problems they may have because they are Mexican. The STOP, THINK and ACT application used a bullying situation where a Mexican peer’s backpack is taken and the child is threatened if they tell on the bully. The group then defines what the problem is (STOP) and guided to describe feelings. The next step (THINK) is to list choices in response to the problem. Finally, the solution is identified (ACT) and the children practice a response. Homework for the children includes take home questions for their mothers: What things did I do when I was younger that made you feel proud? What were your greatest hopes for me since I was 5 years old?

Control Condition

Mothers and children in the control condition received data collection home visits following the same procedures as those in the intervention condition. All mothers and children were screened for depression at each data collection visit. Mothers who reported scores above the established cut-point for referral (1.75 on the HSC) received a phone call from the study project assistant, who was bilingual, bicultural Mexican American woman, with a referral for follow up. Mothers were also called and given referrals for their children if scores on the CDI were at or above 11 or if their child endorsed item nine, suicide ideation. Suicide ideation included responses to three possibilities: I do not think about killing myself (item score 0), I think about killing myself, but would not do it (item score 1) or I want to kill myself (item score 2).

Data analysis

Intention to treat was the analytic design (Friedman, Furberg, & DeMets, 1998; Gross & Fogg, 2004), thus all participants’ assessment data were utilized without consideration for dose or drop out. We utilized Ruben’s Hot deck imputation, (1987) to account for missing data. Hot deck imputation does not have the bias of mean substitution and unlike multiple imputation approaches, does not change the shape of the distribution. We computed descriptive statistics to identify changes in the outcome measures at baseline, follow up at 20 weeks and at 60 weeks after baseline. Then we utilized repeated measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to test the significance of changes in the scores.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Means, standard deviations, and reliability coefficients for measures at baseline for the total sample are presented in Table 3. There were no statistically significant differences in outcome scores by group or neighborhood at baseline for children’s personal characteristics (Child Health Self Concept, CHSC or Global Self Worth), depression (Children’s Depression Inventory, CDI), suicidal ideation, (SI, item #9 on the CDI), or school behaviors (social habits, SH or work habits, WH). There were also no statistically significant differences among mothers’ mental health scores (Hopkins Symptom Checklist, HSC) at baseline. There were statistically significant differences in family communication scores (Family Problem Solving Communication, FPSC) at baseline with the mean scores for FPSC, 21.5 (SD 5.07) on the north side and 23.6 (5.38) on the south side neighborhood (FPSC neighborhood difference, t = −3.4, df = 300, p = 0.001). Higher scores indicate more affirming communication contrasted to lower scores indicating more incendiary communication.

Table 3.

Means (M), standard deviations (SD), range and reliability coefficients of MAPS conceptual variables and measures at baseline (N = 302 mothers and 302 children)

| MAPS Concept (variable) | Measure | M | SD | Range | Reliability* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | |||||

|

Family adaptation (Family communication) |

Family problem solving communication (FPSC) |

22.73 |

5.35 |

0.00-30.00 |

0.82 |

|

Mental health status (Mother mental health) (Child mental health) |

Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSC) Child depression inventory (CDI) |

1.63 9.22 |

0.51 6.12 |

1.00-3.48 0.00-35.0 |

0.94 0.81 |

|

School Adjustment (Performance) |

Work habits (Report Card) |

0.76 |

1.27 |

0.00-6.00 |

NA |

| Adaptation Risk | |||||

|

Social Influence (Acculturation) (Family environment) Family resilience Family functioning b |

Acculturation and Structural Assimilation Scale (ASAS) Family Hardiness Scale (FHS) Feetham Family Function Scale |

40.33 42.94 30.09 |

11.89 7.88 18.85 |

23.00- 90.00 15.00-59.0 0.00-79.00 |

0.86 0.78 0.86 |

|

Previous experience (Maternal stress) (Child stress) |

Everyday stress index (ESI) Stress Index (SI) |

69.30 4.05 |

17.13 2.43 |

33.00- 117.0 0.00-11.00 |

0.90 NA |

|

Child Personal Characteristics (Child health conceptions) Self-esteem |

Child Health Self Concept Scale(CHSC) Global Self- Worth (GSW) |

137.15 18.60 |

16.36 3.43 |

100.00- 180.00 8.00-24.00 |

0.87 0.62 |

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient

Higher scores indicated poorer family functioning

MAPS Outcomes

Outcome measures were assessed at 20 and 60 weeks post baseline. The 20 week assessment occurred within one week after the interventions. Because the baseline scores for the FPSC were statistically different between neighborhoods, neighborhood was included in the analysis. See Table 4 for a summary of statistically significant outcome variable means and standard deviations at baseline, 20 and 60 weeks post baseline across intervention and control groups and the north and south sides.

Table 4.

Significant outcome measures means and standard deviations at Time 1 (baseline), Time 2 (20 weeks post baseline) and Time 3 (60 weeks post baseline) by intervention condition and by neighborhood

| Neighborhood | North | South | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 |

|

CDI Intervention Control |

10.11 (5.98) 8.50 (5.14) |

6.66* (5.16) 7.77 (5.63) |

6.70 (6.54) 6.92 (5.09) |

9.18 (6.27) 9.13 (6.78) |

7.93 (5.96) 7.69 (7.40) |

7.48 (5.78) 5.96 (6.08) |

|

Work habits Intervention**** Control |

6.55 (1.02) 6.58 (1.00) |

6.37 (1.02) 6.50 (0.91) |

6.92 (1.31) 7.42 (1.67) |

6.72 (1.26) 6.89 (1.54) |

6.23 (0.59) 6.97 (1.78) |

6.82 (1.21) 7.04 (1.33) |

|

CHSC Intervention*** Control |

135.05 (15.03) 137.22 (15.25) |

142.88 (17.37) 134.80 (15.19) |

141.56 (19.65) 138.89 (15.88) |

135.96 (16.5) 139.66 (17.60) |

142.50 (18.24) 145.33 (19.90) |

143.92 (18.28) 145.99 (19.37) |

|

FPSC Intervention Control |

21.80 (5.39) 21.23 (4.74) |

22.55** (5.95) 19.78 (3.32) |

20.98 (6.08) 20.02 (3.20) |

24.23 (4.76) 23.09 (5.81) |

23.89 (5.99) 23.96 (5.35) |

24.58 (5.40) 24.15 (5.05) |

F = 2.92, p = 0.055

F = 3.34, p = 0.04

F = 3.55, p = 0.03

F = 3.26, p = 0.04

There was no intervention effect for mother’s mental health scores. Mothers’ mental health scores improved in both groups over time. There were also no significant differences in the follow-up scores in children’s social habits or self-esteem between intervention and control groups.

There was some improvement from the intervention in children’s depression scores, though the effect did not reach statistical significance (F = 2.92, p < .055). For child depression, there was a 22.9% improvement in the intervention group, and a 13.9% improvement in the control group. The effect size for this outcome was 0.23.

Child health self concept scores significantly improved in the intervention group (F = 3.55, p < .03). Children’s scores improved 5.0% in the intervention group and 1.7% in the control group. The effect size was 0.27.

School work habits, as reported by summed check marks on the school report card, showed greater improvement in the intervention group at 20 weeks post baseline (F = 3.26, p < .04). Intervention children showed a decrease in check marks compared to no improvement in the control group. The change reflected represents an effect size at 0.36.

The family problem solving communication (FPSC) scores improved 1.7% in the intervention group and decreased 1.3% in the control group. There was an intervention effect in north side schools at time 2 for family communication that was statistically significant (F = 3.34, p =.04). The effect size for family communication was 0.13. The improvements were not sustained at time 3 assessments.

Discussion

The MAPS intervention had significant positive effects on children’s health conceptions, school work and family communication with nearly significant positive effects on child depression. The findings of this study underscore the utility of school-based home visiting programs delivered by nurses to address the needs and risk factors of Mexican immigrant women and their 4th and 5th grade children. Factors attributing to the success of the program include a partnership that began years before the clinical trial and included discussions with mothers in the community and endorsement of school leadership and staff. In addition, mothers and their children were partners in helping us pilot and revise the linked mother-child program. The 83% retention rate also represents a commitment to the MAPS program among all the partners.

The main effects of the intervention centered on children’s health conceptions and school work habits. While children’s symptoms of depression did not improve statistically significantly between intervention and control groups, improvement approached statistical significance (p = .055). Despite the lack of statistical significance, the percent increase in the intervention group (22.9%) was nearly double the improvement in the control group (13.9%) suggesting a clinical significant improvement. It is also important to note, that overall, mothers in both intervention and control conditions reported improved depressive symptoms over time with more improvement in the intervention group. A portion of the improvement in both groups was likely a result of depression screening and referral for both mothers and children with scores above the clinical cut point. Previous research has demonstrated the positive effect of “extratherapeutic change” such as screening and social support on mental health symptoms (Asay & Lambert, 1999, p. 31).

It is important to note that all home visitors and children’s group leaders were bilingual registered nurses with a minimum of a BSN degree. All nurses received standardized training for the intervention and followed an established protocol. In addition, the study Principal and/or Co-Investigators were always available by phone to address problems encountered by the nurses. Mothers discussed a broad range of problems with nurses that were often complex and difficult to solve. Nurses frequently met with the research team and maintained contact by telephone for support. It is unlikely that similar results could be achieved by employing nurses with less than a BSN.

The intervention was originally designed to have school nurses deliver the program in a case management model with each nurse managing a caseload of 5 mothers (for home visits) and then a group of 5 children in addition to their regular school nursing duties. We anticipated this model would work well with the nurses as insiders in the school system, thus maximizing retention efforts. The established scheduling protocol for home visits included setting the next appointment at the present appointment, calling the night before and en route to the appointment. Despite this protocol, the school nurses could not manage a caseload of 5 mothers-child dyads for home-visiting and classes because of mothers’ demanding schedules and frequent need for rescheduling. After the first wave, we had different nurses delivering the home visits and after school classes. Therefore, identifying the effects of individual nurses is not possible.

Response format and burden are major considerations for researchers working with participants with low literacy or with participants who are immigrants. In this study, the data collectors worked closely with participants by reading to them or with them to assure understanding of the surveys. Most mothers and children responded to surveys utilizing Likert response formats without problems. The Cronbach alpha coefficients on all of the measures that mothers completed ranged from 0.78 – 0.94 and the range of Cronbach alpha coefficients for children’s scores was 0.62 – 0.87. The home visits to collect baseline data from mothers and children took approximately 90 minutes. Subsequent surveys were completed in less than 60 minutes. Data collectors gave mothers the option to complete surveys over two visits if they and their child did not have time for completion at a single visit. This strategy was seldom used however it alleviated negative responses to the burden related to data collection.

Participants in the pilot work assured researchers that the ethnicity of data collectors or nurses was not important (Cowell, McNaughton & Ailey, 2000). Ability to speak Spanish and an interest in the family and willingness to work with family time demands were reported to be the critical attributes required of researchers. An openness to rescheduling data collection or intervention appointments fostered positive relationships between participants and the research team. Because the MAPS intervention was conceptualized to assure the decisional control of the mothers, scheduling difficulties, location preferences for data collection and home visits were respected.

Limitations

We identified fairly high levels of depression symptoms among mothers and children in the preliminary work, so we set the safety cut-point for referral on the Child Depression Inventory at the clinical level. The massive referral across intervention and control conditions may have influenced positive changes in the control condition to limit the power of the intervention. Had we used the community cut point for referral for children, the referral rate would have declined from 31% to 9%.

While the purpose of the study was to reduce mental health risk for Mexican immigrant mothers and their children through a problem solving intervention, depressive symptom scores may not be the most sensitive or immediate outcome to measure. A more direct measure would be a problem solving measure such as a self-reported use of the problem solving steps or use of resources identified in partnership with the nurse.

The usual challenge in community research is the ability to randomized subjects to intervention and control. Had we initiated randomization of subjects within schools, we might have found cross over effects, so schools were randomized and we assume the individual differences among subjects are random. School mobility rate across intervention and control conditions was comparable at 18% and 19% respectively. Lastly, with the exception of school report card data, our measures are self report. Future research should include additional objective assessments of the mothers’ and children’s outcome variables.

The Family Communication Problem Solving measure was used to account for improvements in problem solving. The significantly higher scores in the Southside neighborhood at baseline could explain the lack of statistically significant improvements at 20 and 60 weeks due to ceiling effects. Further, the measure consists of two scales, incendiary communication and affirming communication, thus suggesting a measure of family communication. A more robust assessment of problem solving would have been a more direct measurement of the Mexican American Problem Solving intervention.

The study did not include any community level variables to account for the influence of neighborhood crime, school stability or socio-economic influence. While the review of census data and crime statistics did not reveal significant differences, an inclusion of neighborhood indicators as well as school stability indicators such as principal or teacher turnover, would have enhanced an explanation of the outcomes. For example, the difference in the children’s class intensity (eight classes on the North side and 4.7 on the southside) may have been a reflection of the intervention schools’ instability on the Southside. One school had three principals in three years and another school had several interim principals during the principal’s prolonged absence due to illness. Future research that includes community level variables would enhance the explanation of the effects of interventions on mental health of school aged children and their families.

Policy implications

There are important school health policy implications: While school health services are limited by funding for mandated programs, a fresh look at prevention programs such as MAPS may produce more positive educational outcomes. A stress reduction focus in schools such as the MAPS simplified steps of Stop, Think and Act, may be an important addition to family intervention activities since stress in families and neighborhoods are significant influences on family mental health. While the MAPS program has influenced small improvements by working with mothers and their children, by adding a school focus to reduce stresses in the school, effects may be more powerful.

Acknowledgments

Funded by NINR R01- NR05009

Contributor Information

Julia Muennich Cowell, Rush University College of Nursing, 600 South Paulina (1080 AAC), Chicago, IL 60612, Julia_cowell@rush.edu.

Diane McNaughton, Rush University College of Nursing, 600 South Paulina (1080 AAC), Chicago, IL 60612, Diane_b_mcnaughton@rush.edu.

Sarah Ailey, Rush University College of Nursing, 600 South Paulina (1080 AAC), Chicago, IL 60612, Sarah_h_ailey@rush.edu.

Deborah Gross, Leonard and Helen R. Stulman Professor in Mental Health and Psychiatric Nursing, School of Nursing and School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University, 525 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21218, debgross@jhu.edu.

Louis Fogg, Rush University College of Nursing, 600 South Paulina (1080 AAC), Chicago, IL 60612, Lou_fogg@rush.edu.

References

- Adams-Wheeler K, Gross DA. Societal stress: A model on parenting in a low income minority population. Rush University College of Nursing; 1997. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Asay TP, Lambert MJ. The empirical case for the common factors in therapy: Quantitative findings. In: Hubble MA, Duncan BL, Miller SD, editors. The heart and soul of change: What works in therapy. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Attar BK, Guerra NG, Tolan PH. Neighborhood disadvantage, stressful life events, and adjustment in urban elementary school children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1994;23:391–400. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera MJ, Prelow HM, Dumka LE, et al. Pathways from family economic conditions to adolescents’ distress: Supportive parenting, stressors outside the family and deviant peers. Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Codina GE, Montalvo FF. Chicano phenotype and depression. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Science (suppl 7) 1994;16(3):296–306. [Google Scholar]

- Cowell JM, Gross D, McNaughton D, Ailey S, Fogg L. Depression and suicidal ideation among Mexican American school-aged children. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2005;19:77–94. doi: 10.1891/rtnp.19.1.77.66337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell JM, McNaughton DB, Ailey S. Development and evaluation of a Mexican immigrant family support program. Journal of School Nursing. 2000;16:4–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CL. A model of health behavior to guide studies of childhood cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2003;30(5):E92–99. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.E92-E99. Online Exclusive. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I, Roberts R. Relations of depression, acculturation, and socioeconomic status in a Latino sample. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1997;19(2):230–238. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff J, Gonzales NA, Sandler IN. Control beliefs as a mediator of the relation between stress and depressive symptoms among inner-city adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:205–217. doi: 10.1023/a:1022582410183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis JM, Parke RD, Coltrane S, Blacher J, Borthwick-Duffy SA. Economic pressure, maternal depression, and child adjustment in Latino families: An exploratory study. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 2003;24:183–202. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science. 1974;19:1–5. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830190102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108(108):50–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Lopez VA, Carter SJ. Parenting interventions adapted for Latino families: Progress and prospects. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino Children and Families in the United States: Current Research and Future Directions. Praeger; Westport, CT: 2002. pp. 203–232. [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Kolody B, Vega WA. Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LM, Furberg CD, DeMets DL. Fundamentals of clinical trials. 3rd ed Springer; NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Garber, Martin . Negative cognitions in offspring of depressed parents: Mechanisms of risk. In: Goodman SH, Gotlib IH, editors. Children of Depressed Parents. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gomby DS, Culross PL, Behrman RE. Home visiting: Recent program evaluations-analysis and recommendations. The Future of Children. 1999;9(1):4–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Pitts SC, Hill NE, Roosa MW. A mediational model of the impact of interparental conflict on child adjustment in a multiethnic, low-income sample. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:365–379. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Transmission of risk to children of depressed parents: Integration and conclusions. In: Goodman, Gotlib, editors. Children of Depressed Parents. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2002. pp. 307–326. [Google Scholar]

- Gross DA, Fogg LF. A critical analysis of the intent-to-treat principle in prevention research. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2004;25(4):475–489. [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Sambrook A, Fogg L. Behavior problems among young children in low-income urban day care centers. Research in Nursing and Health. 1999;22(1):15–25. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199902)22:1<15::aid-nur3>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunbaum J, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2003. MMWR. 2004 May 21;53(SS-2) 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall LA. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms in mothers of young children. Public Health Nursing. 1990;7(2):71–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1990.tb00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development. 1982;53:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazuda H, Stern M, Haffner S. Acculturation and assimilation among Mexican Americans: Scales and population-based data. Social Science Quarterly. 1988;69:687–706. [Google Scholar]

- Heilemann MV, Lee KA, Kury FS. Strengths and vulnerabilities of women of Mexican descent in relation to depressive symptoms. Nursing Research. 2002;51(3):175–182. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200205000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester NO. Child’s health self-concept scale; its development and psychometric properties. Advances in Nursing Science. 1984;7:45–55. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198410000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey JD. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation in Mexican immigrants. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2000;6(2):134–151. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.6.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illinois State Board of Education Interactive Illinois report card. Available at: http://iirc.niu.edu/default.html.

- Kovacs M. The children’s depression inventory. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s depression inventory: Manual. Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; North Tonawanda, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Masi R, Cooper J. Children’s mental health: Facts for policymakers. Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health: National Center for Children in Poverty; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin MA, McCubbin HI, Thompson AI. Family hardiness index (FHI) In: McCubbin HI, Thompson AI, McCubbin MA, editors. Family assessment: Resiliency, coping and adaptation - Inventories for research and practice. University of Wisconsin System; Madison: 1986. pp. 239–305. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin MA, McCubbin HI, Thompson AI. Family problem solving communication (FPSC) In: McCubbin HI, Thompson AI, McCubbin MA, editors. Family assessment: Resiliency, coping and adaptation-inventories for research and practice. 1996th ed. University of Wisconsin System; Madison: 1988. pp. 639–686. [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin HI, Thompson AI, McCubbin MA. Family assessment: Resiliency, coping and adaptation: Inventories for research and practice. University of Wisconsin; Madison, WI: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton DB, Cowell JM, Gross D, Fogg L, Ailey SH. The relationship between maternal and child mental health in Mexican immigrant families. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2004;18:229–242. doi: 10.1891/rtnp.18.2.229.61283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munet-Vilaro F, Folkman S, Gregorich S. Depressive symptomatology in three Latino groups. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1999;21(2):209–224. doi: 10.1177/01939459922043848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray NG, Low BJ, Hollis C, Cross AW, Davis SM. Coordinated school health programs and academic achievement: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of School Health. 2007;77(9):589–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter LW. Job attitudes in management: Part I. Perceived deficiencies in need fulfillment as a function of job level. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1962;46(6):375–384. [Google Scholar]

- Porter LW. Job attitudes in management: Part II. Perceived importance of needs as a function of job level. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1963a;47(2):141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Porter LW. Job attitudes in management: Part III. Perceived deficiencies in need fulfillment as a function of line versus staff type of job. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1963b;47(4):267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen RY. Suicidal thinking among adolescents with a history of attempted suicide. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:1294–1300. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199812000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts CS, Feetham SL. Assessing family functioning across three areas of relationships. Nursing Research. 1982;31(4):231–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado de Snyder VN, Cervantes RC, Padilla AM. Gender and ethnic differences in psychosocial stress and generalized distress among hispanics. Sex Roles. 1990;22(7/8):441–453. [Google Scholar]

- Saylor CF, Finch AJ, Spirito A, Bennett B. The children’s depression inventory: A systematic evaluation of psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52(6):955–967. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau The American community-Hispanics: 2004. [Accessed November 12, 2007]. 2007. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2007pubs/acs-03.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Healthy people 2010: Understanding and improving health. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity. A supplement to Mental Health: A report of the Surgeon General. The author; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services SAMSHA model programs. [Accessed February, 12, 2007]. Available at: http://modelprograms.samhsa.gov/template.cfm?page=nreppover.

- United States Government Fiscal Year 2002 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. n.d. Retrieved August 29, 2003, from http://www.immigration.gov/graphics/shared/aboutus/statistics/IMM02yrbk/IMM2002list.htm.

- United States Surgeon General Culture, race and ethnicity. A supplement to mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. n.d. Retrieved April 15, 2003 from http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/mentalhealth/cre/fact3.asp.