Abstract

Objective

Most tests of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for youth anxiety disorders have shown beneficial effects, but these have been efficacy trials with recruited youths treated by researcher-employed therapists. One previous (non-randomized) trial in community clinics found that CBT did not outperform usual care (UC). We used a more stringent effectiveness design to test CBT vs. UC among youths referred to community clinics, with all treatment provided by therapists employed in the clinics.

Method

RCT methodology was used. Therapists were randomized to (a) training and supervision in the Coping Cat CBT program or (b) UC. Forty-eight (48) youths (56% girls; aged 8–15; 38% Caucasian, 33% Latino, 15% African-American) diagnosed with DSM-IV anxiety disorders were randomized to CBT or UC.

Results

At the end of treatment more than half the youths no longer met criteria for their primary anxiety disorder, but the groups did not differ significantly on symptom (e.g., parent report η2=.0001; child report η2=.09, both differences favoring UC) or diagnostic outcomes (CBT: 66.7% without primary diagnosis; UC: 73.7%; OR=.71). No differences were found with regard to outcomes of comorbid conditions, treatment duration, or costs. However, youths receiving CBT used fewer additional services than UC youths (χ2(1) = 8.82, p = .006).

Conclusions

CBT did not produce better clinical outcomes than usual community clinic care. This initial test involved a relatively modest sample size; more research is needed to clarify whether there are conditions under which CBT can produce better clinical outcomes than usual clinical care.

Keywords: child and adolescent anxiety disorders, effectiveness research, cognitive-behavioral therapy

Before large-scale dissemination of evidence-based treatments (EBTs) is undertaken, a number of scientists recommend effectiveness studies, to test the mettle of EBTs across diverse settings, providers, and consumers.1 Effectiveness studies will, for example, recruit the heterogeneous patient populations that are characteristic of everyday clinical practice, train agency-employed therapists instead of graduate students and postdoctoral fellows, and conduct the research in community clinic settings to test the transportability of EBTs. Increasing the diversity and clinical representativeness of conditions permits researchers to examine how a treatment performs across different settings and to identify and address barriers that may interfere with implementation and ultimately dissemination.2, 3

Research on treatment of childhood anxiety disorders has clearly reached a point at which effectiveness research is needed. Dozens of studies support the potency of cognitive behavioral treatments (CBT) for child anxiety disorders.4 However, it is only recently that anxiety RCTs have included active control groups.5–7 Further, very few studies have been conducted outside the “research/lab clinic”,8–10 and none of these has used a fully randomized design. In the study using the closest approach to randomization and clinically representative conditions, Barrington et al.8 compared individual CBT to usual care (UC) in a child mental health care system in Australia. Youth (ages 7–14) who had been referred to community clinics were randomly assigned to UC or CBT. Staff clinicians were assigned non-randomly to CBT or UC, with therapists who had previous CBT experience assigned to CBT. Overall, improvements were found on most anxiety measures from pre- to post-treatment, but there were no significant outcome differences between CBT and UC.

In the present study, we improved on the Barrington et al. design by conducting the first fully-randomized controlled trial (i.e., with clients and therapists randomized to treatment condition) comparing an empirically-supported manualized CBT intervention (Coping Cat)11 to UC in publicly funded clinics. Clients who had been referred to community clinics through normal referral pathways were treated in those clinics by clinicians who were employed there. Our study extends past findings by incorporating design elements not employed in past studies: (a) including only youths with primary DSM-IV12 anxiety disorders, (b) including only therapists employed in the same clinics where cases were treated, (c) randomly assigning therapists and youths to either CBT or UC, (d) using a specific, manual-guided EBT supported by multiple previous RCTs (Coping Cat),5, 11, 13and (e) using a structured and uniform training and supervision procedure for all CBT therapists.

Predicting treatment outcomes in the current study was challenging, given that no fully randomized effectiveness trial had been conducted previously. However, given the favorable outcomes of prior efficacy trials and the current study’s emphasis on standardization of training procedures and close supervision, we hypothesized that CBT would produce outcomes superior to UC. We tested CBT vs. UC group differences on symptom and diagnostic outcomes, treatment duration, use of additional clinical services beyond psychotherapy, and estimated costs. The study appears to be the first double-randomized RCT focused on childhood anxiety disorders in which treatment was delivered within public mental health clinics, to clinically-referred youths, by providers who were employees of the clinics.

Method

Participants

Child sample

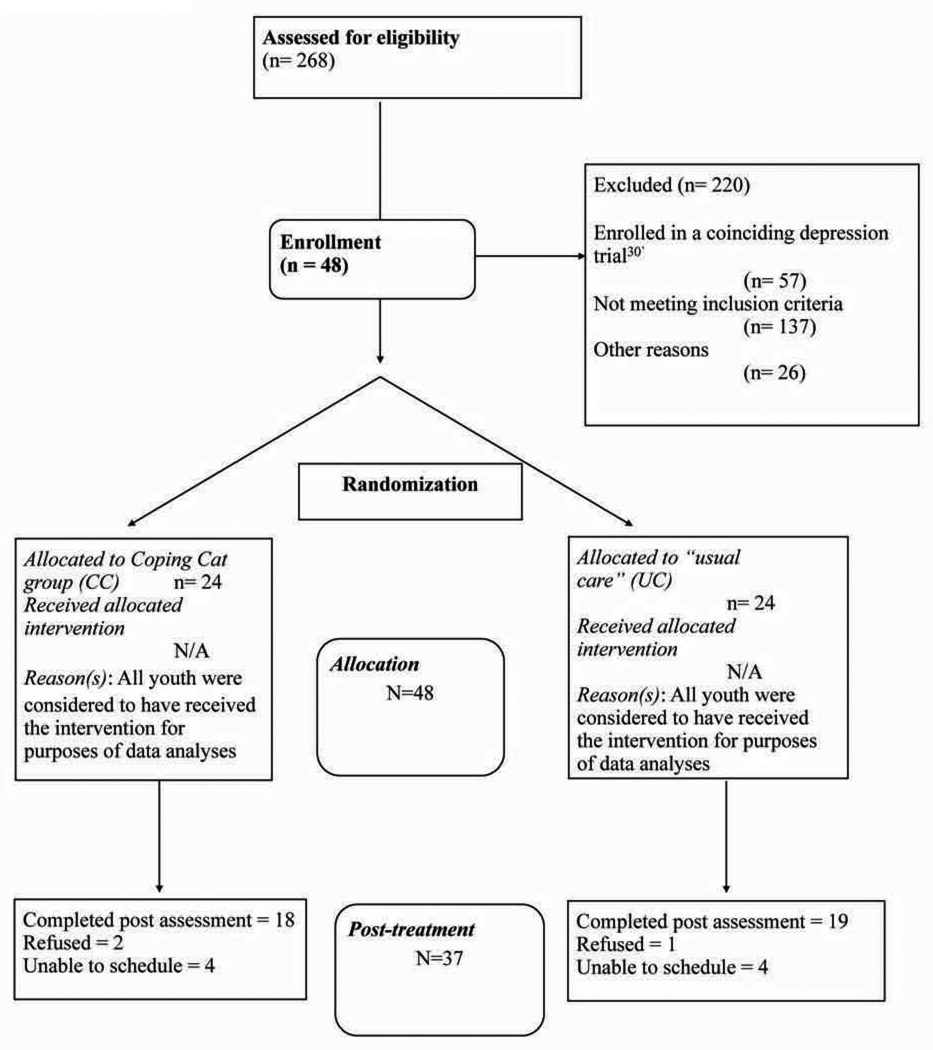

Of the 48 8–15 year-olds (M = 10.9, SD = 2.1) who enrolled in the trial (see CONSORT flowchart, Figure 1), 56.2% were girls; of those reporting ethnicity, 38.5% were Caucasian, 33.3% Latino/Hispanic, 15.4% African-American, 12.8% identified as “mixed/other”; nine participants chose not to report their ethnic background. Annual family income was under $15,000 for 34.9% of families, $15,000–$30,000 for 37.3%, $30,000–$45,000 for 9.4%, $45,000–$60,000 for 4.7%, $60,000–$75,000 for 2.3%, and over $90,000 for 11.4%. Inclusion criteria were (a) age 8–15, and (b) primary DSM-IV diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), separation anxiety disorder (SAD), social phobia (SOP), or specific phobia (SP). Exclusion criteria for the study were diagnosis of: (a) pervasive developmental disorder, (b) a psychotic disorder, or (c) mental retardation.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flowchart

Primary diagnoses (determined using the DISC 4.0, combined parent and child report, discussed later) were 12.5% GAD, 37.5% SAD, 27.1% SOP, and 22.9% SP. Comorbidity was common, with participants meeting criteria for an average of 3.20 (SD = 1.80) diagnoses at the time of the initial assessment. As expected, there was a high proportion of co-occurring anxiety disorders in the sample: 72.9% SP, 52.1% SAD, 43.8% SOP, 27.1 % GAD, 12.5% panic disorder, 6.2% post traumatic stress disorder, and 4.2% obsessive-compulsive disorder. Non-anxiety comorbid disorders were also common: 41.7% ADHD, 37.5% oppositional defiant disorder, 8.3% conduct disorder 8.3% major depressive disorder, and 2.1% dysthymic disorder.

Therapist sample

Therapists (n = 18 in CBT, n = 21 in UC) averaged 33.67 years of age (SD = 9.59, range 25–65; 88.0% females); 51.5% were Caucasian, 30.3% Latino, 6.1% Asian/Pacific, and 12.1% mixed ethnicity. Professionally, 27.3% were social workers, 9.1% doctoral-level psychologists, 51.5% masters level psychologists, and 12.1% other (e.g., marriage and family therapists). Therapists averaged 4.40 (SD = 2.20) years of training and 4.90 (SD = 8.20) years of additional professional experience prior to involvement in the study. CBT and UC therapists did not differ significantly on any of these characteristics.

Assessment Schedule and Measures

Pretreatment (T1) assessments were conducted prior to the start of therapy. Post-treatment (T2) assessments were conducted at the end of treatment for both CBT and UC conditions. This approach ensured that outcome assessment would capture the effects of treatment after each child had ended therapy. Multi-rater, multi-domain assessment was informed by Hoagwood et al.’s14 multi-dimensional assessment approach and focused on two outcome dimensions: (a) diagnoses and symptoms, and (b) treatment process and systems impact—including duration, estimated cost, and use of other clinical services.

Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC 4.0)

The DISC 4.0 is a highly structured respondent-based, computer-administered interview in which interviewers ask standard questions requiring simple (e.g., yes/no) answers from interviewees, with responses integrated via standard DISC algorithms. DISC researchers have produced a rich body of reliability and validity data.15–17 Study interviewers were trained to follow exact DISC administration procedures, and interviews were recorded and monitored throughout the study to ensure standardization. All interviewers were blind to condition (CBT vs. UC) throughout the study. Separate DISC 4.0 interviews with parents and children were used to generate combined DSM-IV diagnoses and symptom counts.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children-Trait version (STAIC-T)

The STAIC-T18 is a 20-item self-report scale that measures enduring tendencies to experience anxiety. The measure is supported by extensive psychometric data.19

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children-Parent-Report, Trait version (STAIC-P-T)

The parent form of the STAIC18 is also supported by reliability and validity evidence.20

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL).21

The CBCL is a 118-item parent rating supported by extensive reliability and validity evidence.21 We focused on the broadband Internalizing scale and the Anxious-Depressed narrow-band scale.

Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA)-Service Use Scale. 22

Treatment process and systems impact was assessed using the SACA, a standardized interview identifying child use of multiple mental health services (including outpatient, inpatient, and school-based); reliability and validity are well-documented.22–24

Clinic record review

Clinic records were retrieved to obtain data on treatment duration and to calculate billing and cost summaries. Cost of treatment (summing across all payers) was estimated for each child by adding the costs of (a) therapist time; (b) psychiatrist time; (c) medications for anxiety; and (d) weekly clinic administrative costs.

Procedures

Setting/recruitment

Participants were told about the study during routine intake procedures at six public, urban, community mental health clinics. After the IRB-approved assessment sequence, youths were invited to participate in the treatment phase if they (a) met DSM-IV criteria for one (or more) anxiety disorders (i.e., GAD, SAD, SOP, SP), and (b) anxiety was considered the treatment priority by the family. During pretreatment assessment parents and youths reported their top three reasons for seeking services (parent examples: “He worries too much,” “has a lot of fears”; youth examples: “afraid to go to school,” “too anxious”) and rated impairment for each on a 0 (no problem at all) to 10 (huge problem) scale. Diagnosis, symptom, referral problem, and impairment data were discussed by project staff, senior clinic staff, and the family; if it was agreed that one of the four anxiety disorders constituted the family’s treatment priority, the youth was invited to enroll in the trial.

Randomization of children and therapists

Youths were assigned to either UC or CBT using block randomization25 to support balance on clinic, child gender, and bilingual requirement (i.e., bilingual therapist required if parent preferred Spanish). Youths with identical status on the three dimensions were blocked in pairs and randomly assigned within blocks. Therapists were also assigned to UC or CBT using a randomized block procedure25 to balance inclusion of bilingual therapists and representation of disciplines. In total, 21 therapists were assigned to the usual care group and 18 were assigned to the CBT group. Therapists only provided one of the two conditions in the study.

Treatment procedures

Therapists assigned to UC agreed to use the treatment procedures they regularly used and believed to be effective in their clinic practice. Therapists assigned to CBT were trained to use Coping Cat (CC), an empirically supported, manual-based, 16–20 session CBT program for childhood anxiety disorders.26 The treatment emphasizes anxiety management skills training (relaxation, identifying and challenging unrealistic anxious thoughts, problem-solving, rewarding approach behavior) and gradual imaginal and in vivo exposure experiences. CBT therapists received a one-day, six-hour training and were then supervised weekly by one of two doctoral-level psychologists with expertise in CC. UC therapists received the case supervision that was standard practice in their clinic. Decisions about adjunctive medication were made according to usual clinic procedures in both CBT and UC conditions. Medication use was tracked during treatment. Therapists in both conditions were permitted to suggest additional services as warranted; further, families were free to seek additional services during the study. We measured any such additional services received with the SACA (described earlier).

Treatment adherence

CBT treatment sessions were coded for treatment adherence using an 11-item treatment integrity checklist, based on the checklist used in Kendall11 and Kendall et al.13 The 11 items reflected whether or not a session included specific elements of CC as identified in the treatment manual (e.g., relaxation, identification and modification of anxious self-talk, exposures). We restricted coding of tapes to those cases with at least six session tapes to provide adequate sampling of procedures. Eleven cases were randomly selected from this subsample (45.8% of the CC sample), and one of two expert (doctoral-level psychologist or clinical psychology doctoral student) raters coded all available tapes for each case. Nine percent of all coded tapes were selected randomly and coded by a second rater; inter-rater agreement achieved a kappa of 0.82.

Therapy Process Observational Coding System for Child Psychotherapy – Strategies Scale (TPOCS-S)27

We used the TPOCS-S to characterize the therapy provided in UC and to assess treatment differentiation between the CC and UC conditions. We used five TPOCS-S subscales: CBT-generic, CBT-Coping Cat (six interventions specific to the Coping Cat protocol), Psychodynamic, Family, and Client-Centered. TPOCS-S coders make 7-point extensiveness ratings on each item—i.e., for the extent to which the therapist used each intervention during an entire session. Five graduate students and one doctoral level clinical psychologist comprised the coding team. Sessions were sampled from each case for which we had pre- and post-treatment outcome data (UC = 19, CC = 14). To sample sessions across UC and CC, one session was randomly sampled from the first and second half of therapy. If a case had more than 20 sessions, three sessions were randomly sampled. The sampling procedure produced a total of 70 coded sessions (39 UC and 31 Coping Cat sessions). Each session was double-coded, and intraclass correlations (ICC) showed acceptable interrater reliability at the subscale level, ICC(1, 6) = .85, SD = .09 (range from .72 to .94).

Data Analysis Plan

Two sets of primary analyses were conducted: logistic regression for diagnostic outcomes (i.e., primary diagnosis absent or present), and analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) for parent- and child-report symptom measures with treatment condition as IV and anxiety at pre-treatment as covariate. Secondary analyses were conducted to examine the impact of comorbid diagnoses, differential adjunctive service use across treatment conditions, duration of treatment, and estimated cost of treatment. Because some of our analyses involved conducting multiple tests, we adjusted alpha to minimize Type I errors using the modified Bonferroni procedure described by Holm,28, 29 across each family of tests (i.e., child-report, parent-report).

Results

Overview

Data preparation and preliminary analyses included: (a) data reduction, (b) handling of missing data, (c) preliminary analyses (e.g., group comparability), and (d) treatment adherence assessment.

Data reduction

We used exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to identify latent factors underlying the parent-and youth-report anxiety measures30 to reduce the number of statistical tests and because we sought to make inferences about latent constructs (i.e., anxiety) rather than specific outcome measures. Tests of normality showed generally normal distributions. Maximum-likelihood estimation produced two factors based on a scree-test. We used an oblique promax rotation31 to identify the two-factor solution with the simplest structure. One factor, parent-reported anxiety, included all parent-report anxiety measures—STAIC-T-P, DISC-P anxiety symptoms, and CBCL anxious-depressed. The other factor, youth-reported anxiety, included both youth-report anxiety measures—STAIC-T and DISC-C anxiety symptoms. We used a unit weighting procedure32 to calculate factor scores: we averaged standardized values of each factor’s measures to compute a factor score for each participant. To obtain post-treatment factor scores on metrics comparable to those of the pre-treatment factors, we standardized each of the post-treatment factor’s measures using the measures’ pre-treatment means and standard deviations.

Missing data

We checked for systematic patterns in our missing data by testing for differences on all clinical and demographic variables, comparing participants missing any data at either assessment to those missing no data at either assessment. These analyses revealed no significant differences, suggesting that the data were missing completely at random (MCAR).29

Group comparability

To check the effectiveness of our randomized block design, we compared the two groups at pre-treatment (T1) on potential moderating outcome variables. We used t-tests for continuous measures, chi-square tests for categorical measures. Tests encompassed child-report clinical measures, parent-report clinical measures and sociodemographic variables. These analyses showed no significant differences between treatment groups on any pre-treatment measure (see Table 1). Similar analyses were used to test for clinic differences in clinical and sociodemographic variables at pre-treatment; no significant clinic effects were found.

Table 1.

Descriptive Data at Pre-and Post-treatment, by Treatment Group.

| Pretreatment | Posttreatment | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UC | CBT | UC | CBT | |||||||||

| M | SD | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | |

| Child Self-report | ||||||||||||

| STAIC-Trait | 35.75 | 7.25 | 24 | 34.33 | 6.12 | 24 | 29.68 | 6.81 | 19 | 36.53 | 9.86 | 17 |

| DISC-C Anx sx count | 17.19 | 8.33 | 24 | 19.42 | 7.88 | 24 | 6.21 | 6.97 | 14 | 11.15 | 7.66 | 17 |

| Child Anxiety Factor | −0.02 | 0.97 | 24 | 0.02 | 0.81 | 24 | −1.01 | 0.98 | 19 | −0.29 | 1.07 | 18 |

| Parent report | ||||||||||||

| STAIC-P-Trait | 45.21 | 8.22 | 24 | 46.52 | 7.91 | 21 | 41.80 | 7.88 | 19 | 42.75 | 8.89 | 16 |

| CBCL Anx/Dep | 68.65 | 8.61 | 20 | 67.65 | 9.09 | 23 | 58.94 | 9.04 | 17 | 60.19 | 8.46 | 16 |

| CBCL Internalizing | 66.30 | 8.23 | 20 | 66.52 | 9.23 | 23 | 56.12 | 10.36 | 17 | 58.87 | 9.03 | 15 |

| DISC-P Anx sx count | 20.75 | 7.45 | 24 | 19.17 | 8.80 | 24 | 9.08 | 7.97 | 19 | 10.77 | 8.11 | 17 |

| Parent Anxiety Factor | −0.002 | 0.81 | 24 | 0.03 | 0.90 | 24 | −0.94 | 0.84 | 19 | −0.82 | 0.80 | 18 |

| DISC-P DBD diagnoses | 1.00 | 0.78 | 24 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 24 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 19 | 0.39 | 0.61 | 18 |

| Combined report | ||||||||||||

| DISC- Anx diagnoses | 2.28 | 1.22 | 24 | 2.17 | 1.31 | 24 | 1.21 | 1.62 | 19 | 1.44 | 1.15 | 18 |

| DISC- Dep diagnoses | 0.04 | 0.20 | 24 | 0.25 | 0.54 | 24 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 19 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 18 |

| DISC-Total diagnoses | 3.25 | 1.60 | 24 | 3.17 | 1.93 | 24 | 2.32 | 2.00 | 19 | 1.94 | 1.55 | 18 |

| Other variables | ||||||||||||

| Estimated cost (US$) | 3055.76 | 1301.94 | 24 | 2543.29 | 1740.37 | 24 | ||||||

| Treatment duration (sessions) |

14.00 | 5.92 | 24 | 13.96 | 8.15 | 24 | ||||||

| Treatment duration (wks) | 27.68 | 18.77 | 24 | 21.542 | 13.971 | 24 | ||||||

Note: CBT=cognitive-behavioral therapy group; CBCL Anx/Dep = Child Behavior Checklist-Anxiety/Depression Scale; CBCL Internalizing = Child Behavior Checklist-Internalizing Behavior Scale; DISC- Anx diagnoses= total number of comorbid (non-primary) anxiety diagnoses on Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, composite report; DISC-C anx sx count=number of anxiety disorder symptoms (social phobia, separation anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and specific phobia only) on child-report Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children; DISC- Dep diagnoses= total number of comorbid depressive disorder diagnoses on Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, composite report; DISC-P anx sx count = number of anxiety disorder symptoms (social phobia, separation anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and specific phobia only) on parent-report Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children; DISC-P DBD Diagnoses = Number of disruptive behavior disorder diagnoses on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-Parent report; DISC-Total diagnoses: total number of diagnoses on Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, composite report; STAIC-P-Trait = State Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children, Trait version, parent report; STAIC-Trait = State Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children, Trait version; UC=usual care group

Coping Cat adherence

Treatment adherence coding (described earlier) indicated that 98.9% (range = 87.5–100.0; SD= 3.77) of CC sessions contained the expected procedures.

CBT dose

Coping Cat (CC) includes 16–20 sessions. In the present sample, 54.2% of youths in the CBT group received 16 or more sessions. CC also includes two phases: skills training and exposure, with exposure sessions coming in the second half of treatment. Fifty-eight percent of participants received at least one exposure session, based on therapist report. Our random reviews of tape for adherence indicated a similar proportion (54.5%) Mean number of exposure sessions was 3.92 (SD = 4.01; range 0–12) for the full CBT sample (n=24) and 6.71 (SD = 2.87; range 2–12) for those youth receiving any exposures (n=14).

UC Content

To characterize UC, we produced mean TPOCS-S item scores across therapy sessions and then averaged across items to produce subscale scores (range 1–7). UC therapists had higher ratings on the Client-Centered (M = 3.66, SD = .84) than on the CBT-generic (M = 2.02, SD = .35); t(18) = 9.68, p < .001), Psychodynamic (M = 2.13, SD = .85; t(18) = 6.96, p < .01), and Family (M = 2.37, SD = 1.10; t(18) = 4.19, p < .01) subscales. No other comparisons yielded statistically significant differences. In general, we found that the UC therapists used a range of treatment procedures consistent with multiple theoretical orientations.

Distinctness of UC and CBT

We compared the two conditions using TPOCS-S-coded tapes for 19 UC and 14 CBT cases. When mean TPOCS-S subscale scores were compared for the two groups, the UC cases scored significantly higher than CBT cases on the Psychodynamic (t(31) = 3.71, p < .01; UC M = 2.13, SD = .85; CBT M = 1.27, SD = 1.27), Family (t(31) = 3.46, p < .05; UC M = 2.37, SD = 1.10; CBT M = 1.29, SD = .39), and Client-Centered (t(31) = 2.52, p < .01; UC M = 3.66, SD = .84; CBT M = 3.03, SD = .45) subscales. The UC and CBT groups did not significantly differ on the CBT-generic subscale (t(31) = .83, p = ns; UC M = 1.90, SD = .42; CBT M = 2.02, SD = .35). On the CBT-Coping Cat subscale, CBT cases scored significantly higher than UC cases (t(31) = 4.13, p < .001; UC M = 1.62, SD = .35; CBT M = 2.24, SD = .52).

Primary Analyses

Power analyses

We calculated power to detect medium and large effect size differences between UC and CBT for our ITT (n=48) and post-treatment samples (n=37). For the ITT sample (n=48), our power was .97 for large effects and .69 for medium effects. For the final post-treatment sample (n=37), our power was .93 for large effects and .58 for medium effects.

Diagnostic analyses

We applied logistic regression analyses to our diagnostic data in two ways: (a) for participants with diagnostic data available at post-treatment and (b) for the full sample, as intent to treat (ITT), with those missing post-treatment data having the last value carried forward. For participants with post-treatment diagnostic data available, 73.7% of UC and 66.7% of CC no longer met criteria for their primary anxiety disorder, a difference that was not statistically significant, Odds Ratio (OR) = 0.71 (95% CI: 0.17 – 2.94); likelihood ratio, χ2 (1) = .22, p = .64. For the ITT sample, primary diagnosis-free rates were attenuated such that 58.3% of UC and 50.0% of CC no longer met diagnostic criteria for their primary disorder, a difference that was also not statistically significant, OR = 0.71 (95% CI: 0.23– 1.23); likelihood ratio, χ2 (1) = .34, p = .56.

Symptom analyses

Neither of the two ANCOVAs showed a significant effect for treatment group: child-report, F (1, 34) = 2.53, p = .07 (marginal difference favoring UC), |2=.09 and parent-report F (1, 34) = .001, p = .96, |2=.0001.

Secondary analyses

Comorbidity outcomes

We used ANCOVA to test for group difference on reduction in the number of comorbid diagnoses, covarying the number of comorbid diagnoses at pretreatment. The group difference was not statistically significant, F (1, 34) = 0.71, p = .40, |2=.02.

Additional services used

A significantly greater proportion of UC than CC families received additional mental health services concurrent with treatment (41.0% in UC vs. 0.0% in CC; χ2(1) = 8.82, p = .006). Examples included seeking care from another mental health provider (e.g., a second therapist, school-based services). No significant group difference was evident in use of psychotropic medication to treat anxiety, χ2(1) = .36, p = .55 (8.0% for UC and 4.0% for CC).

Treatment duration

Group differences in mean treatment duration gauged by weeks and sessions (see Table 1) were not statistically significant: weeks: t(46)= 1.28, p = .21, d = .36; sessions: t(46)= 0.20, p = .98, d = .01.

Cost

Concerning cost (calculation described earlier), we found no statistically significant difference between the two groups, t(42.60) = 1.16, p = .25, d = .33.

Discussion

We conducted an initial effectiveness study in which the outcomes generated by an evidence-based treatment for youth anxiety (i.e., Coping Cat) provided by therapists who received training and supervision in the program were compared to the outcomes of UC in several public mental health clinics. We tested for treatment effects across a variety of outcomes. Youths in both the CBT and UC conditions exhibited improved diagnostic outcomes: more than half the ITT sample and more than two-thirds of children for whom we had post-treatment data (66.7% in CBT and 73.7% in UC) no longer met diagnostic criteria for their primary anxiety disorder. The proportion of youth in the Coping Cat condition who no longer met diagnostic criteria for their primary diagnosis compares favorably to the proportions in past Coping Cat efficacy studies5, 11, 13 and in the Barrington et al. trial. 8 Similarly, the proportion of youth in the UC group who no longer met diagnostic criteria for their primary diagnosis was comparable to that found in CBT groups in prior Coping Cat trials and in the Barrington et al. trial. Symptom outcomes were similar to diagnostic outcomes in pattern. Youths in both conditions exhibited improvement from pre- to post-treatment but there were no statistically significant differences between the CBT and UC groups. The pattern of no treatment group differences held across all but one secondary outcome, including duration of treatment, estimated cost of services, and impact of treatment on comorbid disorders. The one significant group difference was that CBT youth used significantly fewer additional services during treatment compared to the UC group, a finding we discuss shortly. Overall, our data suggest that the CBT intervention achieved outcomes within the range of previous trials using Coping Cat, but that it did not outperform UC.

There are a few key findings relevant to the potency of the CBT condition in the present study. First, therapists newly trained and supervised to provide CBT in public mental health clinics to clients with primary anxiety disorders and complex clinical pictures were able to (a) obtain good adherence scores, and (b) produce outcomes at levels similar to those in efficacy trials with expert CBT therapists. These results are similar to those reported by Weisz et al.30 in a study of CBT for youth depression and suggest that community therapists can be trained to deliver CBT effectively.

We found that youth in UC received significantly more additional mental health services (e.g., additional therapy, group therapy) than youth in the CBT condition: 41.0% vs. 0.0%, a result similar to that of a recent effectiveness trial of CBT with depressed youth.30 Because most community-based studies8–10 have not reported such systems-level data, it is difficult to place our findings in context. If future work replicates the finding, it may be reasonable to suggest that CBT is a simpler prescription, or is better able to produce effects without supplemental services, than is UC.

A principal goal of effectiveness research is to assess how well specific interventions fare under representative clinical care conditions, conditions that often include less-than-complete delivery of treatment protocols. Such a pattern was evident in our study, with only 52% of youth in the CBT group receiving the full 16 sessions and only 59% receiving exposure sessions. It is possible that CBT outcomes would have been better if all of the youth receiving CBT had received the full dose, including exposures. On the other hand, it is important to note that CBT outcomes in the present sample—despite cases of less-than-complete treatment—were quite comparable to those of prior efficacy trials using Coping Cat5, 11, 13. The non-significant CBT-UC differences we found reflected, not poor CBT outcomes, but instead the positive outcomes of youngsters in the UC condition, outcomes comparable to those of Coping Cat in prior efficacy trials. Thus, the fact that our community clinic youths in the CBT condition did not all complete full Coping Cat protocols did not prevent them from showing treatment gains characteristic of previous efficacy trials.

What then did account for our findings? Experts have noted that multiple levels of the ecology can influence the success of an EBT when transported to a new setting.1 For example, added client complexity (e.g., higher levels of comorbidity, increased levels of ethnic diversity) in community service settings, supported by several studies,33, 34 may complicate the delivery of EBTs. These considerations are relevant to our findings for at least two reasons. First, we did not modify the treatment program, so CBT therapists maintained a focus on anxiety whereas UC therapists were free to attend to and address non-anxiety problems. This is particularly relevant given the high rate of comorbid disorders in our sample. It is possible that the flexibility and latitude of UC afforded an advantage, and it is possible that adapting EBTs to permit focus on multiple problems could yield even better outcomes.3, 35 Second, our design included random assignment of therapists to treatment condition and training and ongoing supervision by experts in the model—procedures that are consistent with efficacy trials; however, therapists in community settings are likely to vary in their training, experience, interest, and comfort in CBT—factors that could have impacted the outcomes of the study.36, 37 By contrast, UC therapists used procedures of their own choice and with which they were presumably experienced; this may have enhanced their confidence and thereby the effectiveness of their treatment. And as our analyses demonstrated, UC therapists apparently included some CBT strategies, suggesting that the CBT approach has been diffused somewhat into usual care.

The study was underpowered to detect anything other than large effects. At the outset of the trial, the early success of Coping Cat11 led us to anticipate medium to large effects, but our actual effects proved similar to those that were later evident in recent comparisons of EBTs to UC comparison groups8, 30. Completing this trial lays the foundation for future double-randomized trials across multiple community clinics, training in-house therapists, and treating community-referred clients, with larger samples.

Two additional issues warrant attention in future research. First, our sample of clients and therapists was quite heterogeneous, increasing error variance and possibly making the delivery of an anxiety-focused CBT program more challenging. Of course, a limitation of this kind that may weaken internal validity may also be viewed as a strength when it amplifies a study’s external validity.38 Studies that focus on the impact of client and therapist heterogeneity on outcome could shed important light on the tradeoffs between efficacy and effectiveness designs. Second, the field lacks relevant measures of competence in the use of CBT with children; such measures would have permitted us to examine how well the CBT program was delivered, beyond adherence to the protocol. Future work developing competence assessment methods could be valuable to the field.39

Considering the study’s blend of strengths and limitations, this appears to be the most rigorous randomized effectiveness trial to date testing an EBT for childhood anxiety disorders compared to an active UC alternative. Our results contribute to a growing body of literature identifying the challenges in documenting differential effects between manual-based and UC treatments. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis of RCTs comparing youth EBTs to UC40 for a variety of clinical problems (e.g., internalizing and externalizing disorders) found only a modest mean effect size favoring EBTs, and in many of the studies there was no significant EBT vs. UC difference in outcome. Interestingly, no RCTs were found for that meta-analysis that involved anxiety treatment and met methodological standards for inclusion. With completion of the present study, there is now one fully randomized trial of CBT vs. UC in the youth anxiety domain and another partially randomized trial;7 both trials have shown no significant difference in outcome between CBT and UC. This suggests a need for considerable research in the days ahead, to determine whether there are conditions under which CBT for youth anxiety can, in fact, outperform the treatments that are routinely provided by clinicians in everyday clinical care.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by a grant from NIMH to Dr. Weisz (R01-MH574347

We thank Philip C. Kendall (Temple University) and Donna K. McClish (Virginia Commonwealth University) for their consultation on the project. We also thank our clinic partners for their help, in many forms, throughout the study. These include Herb Blaufarb, Susan Hall-Marley, and Terry Rattray, (Child and Family Guidance Center); Kita Curry, Cynthia Kelly, and Marian Williams (Didi Hirsch Community Mental Health Center); Anita Feltes (Edelman Westside Mental Health); Jill Morgan and David Slay (Greater Long Beach Child Guidance Center); Joseph Ho, Philip Pannell, and Robert Parsons (Pacific Clinics); and Thomas Ciesla, Carol Falender, Allison Pinto, and Rebecca Refuerzo (St. John’s Health Center). We also thank the therapists, parents, and youths who participated in the study, as well as our project administrative and graduate student colleagues, including Amie Bettencourt, C. Ashley Borders, Jen Durham-Fowler, Aileen Echiverri, Samantha Fordwood, Sarah Francis, Andrea Kasimian, May Lim, Tamara Sharpe, Irina Tauber, and Alanna Updegraff (University of California – Los Angeles); Kristin Hawley (University of Missouri); Amanda Jensen-Doss (University of Miami); David Langer (Judge Baker Children’s Center); Antonio Polo (DePaul University); and V. Robin Weersing (San Diego State University).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: Dr. Southam-Gerow and Dr. McLeod receive financial support from the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Weisz receives financial support from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Norlien Foundation, and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Dr. Chu, Gordis, and Connor-Smith report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Clinical Trials Registry Information -- Community Clinic Test of Youth Anxiety and Depression Study; http://clinicaltrials.gov; NCT01005836

References

- 1.Schoenwald SK, Hoagwood K. Effectiveness, transportability, and dissemination of interventions: What matters when? Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1190. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weisz JR. Psychotherapy for Children and Adolescents: Evidence-Based Treatments and Case Examples. Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Southam-Gerow MA, Hourigan SE, Allin RB., Jr Adapting evidence-based mental health treatments in community settings: Preliminary results from a partnership approach. Behavior Modification. 2009;33:82–103. doi: 10.1177/0145445508322624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverman WK, Pina AA, Viswesvaran C. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for phobic and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:105–130. doi: 10.1080/15374410701817907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kendall PC, Hudson JL, Gosch E, Flannery-Schroeder E, Suveg C. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: A randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:282–297. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silverman W, Kurtines W, Ginsburg G, Weems C, Rabian B, Serafini L. Contingency management, selfcontrol, and education support in the treatment of childhood phobic disorders: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:675–687. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini JC, Birmaher B, Compton SN, Sherrill JT, Ginsburg GS, Rynn MA, McCracken J, Waslick B, Iyengar S, March JS, Kendall PC. Cognitive behavioral therapy, Sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359:2753–2766. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrington J, Prior M, Richardson M, Allen K. Effectiveness of CBT versus standard treatment for childhood anxiety disorders in a community clinic setting. Behaviour Change. 2005;22:29–43. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baer S, Garland EJ. Pilot study of community-based cognitive behavioral group therapy for adolescents with social phobia. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:258–264. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200503000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farrell LJ, Barrett PM, Claassens S. Community trial of an evidence-based anxiety intervention for children and adolescents (the FRIENDS program): A pilot study. Behaviour Change. 2005;22:236–248. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kendall PC. Treating anxiety disorders in children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:100–110. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kendall PC, Flannery-Schroeder E, Panichelli-Mindel SM, Southam-Gerow M, Henin A, Warman M. Therapy for youths with anxiety disorders: A second randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:366–380. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen PS, Hoagwood K, Petti T. Outcomes of mental health care for children and adolescents: II. Literature review and application of a comprehensive model. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1064. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199608000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwab-Stone ME, Shaffer D, Dulcan MK, Jensen PS. Criterion validity of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3) Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:878–888. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubio-Stipec M, Shrout PE, Canino G, Bird HR, Jensen P, Dulcan M, Schwab-Stone M. Empirically defined symptom scales using the DISC 2.3. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology: An official publication of the International Society for Research in Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. 1996;24:67–83. doi: 10.1007/BF01448374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK, Davies M. The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): Description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:865–877. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spielberger CD. Manual for State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for children. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Southam-Gerow MA, Chorpita BF. Anxiety in children and adolescents. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Assessment of childhood disorders (4th Ed) New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 347–397. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Southam-Gerow MA, Flannery-Schroeder EC, Kendall PC. A psychometric evaluation of the parent report form the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children--Trait Version. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2003;17:427–446. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horwitz S, Hoagwood K, Stiffman A, Summerfeld T, Weisz JR, Costello EJ, et al. Reliability of the Services Assessment for Children and Adolescents. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1088–1094. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.8.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoagwood K, Horwitz S, Stiffman A, Weisz JR, Bean D, Rae D, et al. Concordance between parent reports of children's mental health services and service records: The Services Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA) Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2000;9(3):315–331. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stiffman AR, Horwitz SM, Hoagwood K, Compton W, III, Cottler L, Bean DL, Narrow WE, Weisz JR. The Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA): Adult and child reports. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:1032–1039. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200008000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman LM, Furberg CD, DeMets DL. Fundamentals of clinical trials. New York: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kendall PC, Kane M, Howard B, Siqueland L. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of anxious children: Treatment manual. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLeod BD, Weisz JR. The Therapy Process Observational Coding System for Child Psychotherapy Strategies Scale. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:436–443. doi: 10.1080/15374411003691750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaccard J, Guilamo-Ramos V. Analysis of variance frameworks in clinical child and adolescent psychology: Issues and recommendations. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:130–146. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3101_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weisz JR, Southam-Gerow MA, Gordis EB, Connor-Smith JK, Chu BC, Langer DA, McLeod BD, Jensen-Doss A, Updegraff A, Weiss B. Cognitive behavioral therapy versus usual clinical care for youth depression: An initial test of transportability to community clinics and clinicians. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:383–396. doi: 10.1037/a0013877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hendrickson AE, White P. Promax: A quick method for rotation to oblique simple structure. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 1964;17:66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kline RB. Beyond Significance Testing: Reforming Data Analysis Methods in Behavioral Research. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Southam-Gerow MA, Weisz JR, Kendall PC. Youth with anxiety disorders in research and service clinics: examining client differences and similarities. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:375–385. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Southam-Gerow MA, Chorpita BF, Miller LM, Gleacher AA. Are children with anxiety disorders privately referred to a university clinic like those referred from the public mental health system? Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2008;35:168–180. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weisz JR, Chu BC, Polo AJ. Treatment dissemination and evidence-based practice: Strengthening intervention through clinician-researcher collaboration. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11:300–307. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLeod BD. Understanding why therapy allegiance is linked to clinical outcomes. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2009;16:69–72. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perepletchikova F, Kazdin AE. Treatment integrity and therapeutic change: Issues and research recommendations. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2005;12(4):365–383. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weisz JR, Doss AJ, Hawley KM. Youth psychotherapy outcome research: A review and critique of the evidence base. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:337–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barber JP, Sharpless B, Klostermann S, McCarthy K. Assessing intervention competence and its relation to therapy outcome: A selected review derived from the outcome literature. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2007;38:493–500. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weisz JR, Jensen-Doss A, Hawley KM. Evidence-based youth psychotherapies versus usual clinical care: A meta-analysis of direct comparisons. American Psychologist. 2006;61:671–689. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]