Abstract

The MM (minorization–maximization) principle is a versatile tool for constructing optimization algorithms. Every EM algorithm is an MM algorithm but not vice versa. This article derives MM algorithms for maximum likelihood estimation with discrete multivariate distributions such as the Dirichlet-multinomial and Connor–Mosimann distributions, the Neerchal–Morel distribution, the negative-multinomial distribution, certain distributions on partitions, and zero-truncated and zero-inflated distributions. These MM algorithms increase the likelihood at each iteration and reliably converge to the maximum from well-chosen initial values. Because they involve no matrix inversion, the algorithms are especially pertinent to high-dimensional problems. To illustrate the performance of the MM algorithms, we compare them to Newton’s method on data used to classify handwritten digits.

Keywords: Dirichlet and multinomial distributions, Inequalities, Maximum likelihood, Minorization

1. INTRODUCTION

The MM algorithm generalizes the celebrated EM algorithm (Dempster, Laird, and Rubin 1977). In this article we apply the MM (minorization–maximization) principle to devise new algorithms for maximum likelihood estimation with several discrete multivariate distributions. A series of research papers and review articles (Groenen 1993; de Leeuw 1994; Heiser 1995; Hunter and Lange 2004; Lange 2004; Wu and Lange 2010) have argued that the MM principle can lead to simpler derivations of known EM algorithms. More importantly, the MM principle also generates many new algorithms of considerable utility. Some statisticians encountering the MM principle for the first time react against its abstraction, unfamiliarity, and dependence on the mathematical theory of inequalities. This is unfortunate because real progress can be made applying a few basic ideas in a unified framework. The current article relies on just three well-known inequalities. For most of our examples, the derivation of a corresponding EM algorithm appears much harder, the main hindrance being the difficulty of choosing an appropriate missing data structure.

Discrete multivariate distributions are seeing wider use throughout statistics. Modern data mining employs such distributions in image reconstruction, pattern recognition, document clustering, movie rating, network analysis, and random graphs. High-dimension data demand high-dimensional models with ten to hundreds of thousands of parameters. Newton’s method and Fisher scoring are capable of finding the maximum likelihood estimates of these distributions via the parameter updates

where ∇L(θ) is the score function and M(θ) is the observed or the expected information matrix, respectively. Several complications can compromise the performance of these traditional algorithms: (a) the information matrix M(θ) may be expensive to compute, (b) it may fail to be positive definite in Newton’s method, (c) in high dimensions it is expensive to solve the linear system M(θ)x = ∇L(θ(n)), and (d) if parameter constraints and parameter bounds intrude, then the update itself requires modification. Although mathematical scientists have devised numerous remedies and safeguards, these all come at a cost of greater implementation complexity. The MM principle offers a versatile weapon for attacking optimization problems of this sort. Although MM algorithms have at best a linear rate of convergence, their updates are often very simple. This can tip the computational balance in their favor. In addition, MM algorithms are typically easy to code, numerically stable, and amenable to acceleration. For the discrete distributions considered here, there is one further simplification often missed in the literature. These distributions involve gamma functions. To avoid the complications of evaluating the gamma function and its derivatives, we fall back on a device suggested by Haldane (1941) that replaces ratios of gamma functions by rising polynomials.

Rather than tire the skeptical reader with more preliminaries, it is perhaps best to move on to our examples without delay. The next section defines the MM principle, discusses our three driving inequalities, and reviews two simple acceleration methods. Section 3 derives MM algorithms for some standard multivariate discrete distributions, namely the Dirichlet-multinomial and Connor–Mosimann distributions, the Neerchal–Morel distribution, the negative-multinomial distribution, certain distributions on partitions, and zero-truncated and zero-inflated distributions. Section 4 describes a numerical experiment comparing the performance of the MM algorithms, accelerated MM algorithms, and Newton’s method on model fitting of handwritten digit data. Our discussion concludes by mentioning directions for further research and by frankly acknowledging the limitations of the MM principle.

2. OVERVIEW OF THE MM ALGORITHM

As we have already emphasized, the MM algorithm is a principle for creating algorithms rather than a single algorithm. There are two versions of the MM principle, one for iterative minimization and another for iterative maximization. Here we deal only with the maximization version. Let f (θ) be the objective function we seek to maximize. An MM algorithm involves minorizing f (θ) by a surrogate function g(θ|θn) anchored at the current iterate θn of a search. Minorization is defined by the two properties

| (2.1) |

| (2.2) |

In other words, the surface θ ↦ g(θ|θn) lies below the surface θ ↦ f (θ) and is tangent to it at the point θ = θn. Construction of the surrogate function g(θ|θn) constitutes the first M of the MM algorithm.

In the second M of the algorithm, we maximize the surrogate g(θ|θn) rather than f (θ). If θn+1 denotes the maximum point of g(θ|θn), then this action forces the ascent property f (θn+1) ≥ f (θn). The straightforward proof

reflects definitions (2.1) and (2.2) and the choice of θn+1. The ascent property is the source of the MM algorithm’s numerical stability. Strictly speaking, it depends only on increasing g(θ|θn), not on maximizing g(θ|θn).

The art in devising an MM algorithm revolves around intelligent choices of minorizing functions. This brings us to the first of our three basic minorizations

| (2.3) |

invoking the chord below the graph property of the concave function ln x. Note here that all parameter values are positive and that equality obtains whenever for all i. Our second basic minorization

| (2.4) |

restates the supporting hyperplane property of the convex function −ln(c + x). Our final basic minorization

| (2.5) |

is just a rearrangement of the two-point information inequality

Here α and αn must lie in (0, 1). Any standard text on inequalities, for example, the book by Steele (2004), proves these three inequalities. Because piecemeal minorization works well, our derivations apply the basic minorizations only to strategic parts of the overall objective function, leaving other parts untouched.

The convergence theory of MM algorithms is well known (Lange 2004). Convergence to a stationary point is guaranteed provided five properties of the objective function f (θ) and the MM algorithm map M(θ) hold: (a) f (θ) is coercive on its open domain; (b) f (θ) has only isolated stationary points; (c) M(θ) is continuous; (d) θ* is a fixed point of M(θ) if and only if it is a stationary point of f (θ); (e) f [M(θ*)] ≤ f (θ*), with equality if and only if θ* is a fixed point of M(θ). Most of these conditions are easy to verify for our examples, so the details will be omitted.

A common criticism of EM and MM algorithms is their slow convergence. Fortunately, MM algorithms can be easily accelerated (Jamshidian and Jennrich 1995; Lange 1995a; Jamshidian and Jennrich 1997; Varadhan and Rolland 2008). We will employ two versions of the recent square iterative method (SQUAREM) developed by Varadhan and Roland (2008). These simple vector extrapolation techniques require computation of two MM updates at each iteration. Denote the two updates by M(θn) and M ◦ M(θn), where M(θ) is the MM algorithm map. These updates in turn define two vectors

The versions diverge in how they compute the steplength constant s. SqMPE1 (minimal polynomial extrapolation) takes , while SqRRE1 (reduced rank extrapolation) takes . Once s is specified, we define the next accelerated iterate by θn+1 = θn − 2su + s2υ. Readers should consult the original article for motivation of SQUAREM. Whenever θn+1 decreases the log-likelihood L(θ), we revert to the MM update θn+1 =M ◦ M(θn). Finally, we declare convergence when

| (2.6) |

In the numerical examples that follow, we use the stringent criterion ε = 10−9. More sophisticated stopping criteria based on the gradient of the objective function and the norm of the parameter increment lead to similar results.

3. APPLICATIONS

3.1 Dirichlet-Multinomial and Connor–Mosimann Distributions

When count data exhibit overdispersion, the Dirichlet-multinomial distribution is often substituted for the multinomial distribution. The multinomial distribution is characterized by a vector p = (p1,…, pd) of cell probabilities and a total number of trials m. In the Dirichlet-multinomial sampling, p is first drawn from a Dirichlet distribution with parameter vector α = (α1,…,αd). Once the cell probabilities are determined, multinomial sampling commences. This leads to the admixture density

| (3.1) |

where , Δd is the unit simplex in ℝd, and x = (x1,…, xd) is the vector of cell counts. Note that the count total is fixed at m. Standard calculations show that a random vector X drawn from h(x|α) has the means, variances, and covariances

If the fractions tend to constants pi as |α| tends to ∞, then these moments collapse to the corresponding moments of the multinomial distribution with proportions p1,…, pd.

One of the most unappealing features of the density function h(x|α) is the occurrence of the gamma function. Fortunately, very early on Haldane (1941) noted the alternative representation

| (3.2) |

The replacement of gamma functions by rising polynomials is a considerable gain in simplicity. Bailey (1957) later suggested the reparameterization

in terms of the proportion vector π = (π1,…, πd) and the overdispersion parameter θ. In this setting, the discrete density function becomes

| (3.3) |

This version of the density function is used to good effect by Griffiths (1973) in implementing Newton’s method for maximum likelihood estimation with the beta-binomial distribution.

In maximum likelihood estimation, we pass to log-likelihoods. This introduces logarithms and turns factors into sums. To construct an MM algorithm under the parameterization (3.2), we need to minorize terms such as ln(αj + k) and −ln(|α| + k). The basic inequalities (2.3) and (2.4) are directly relevant. Suppose we draw t independent samples x1,…, xt from the Dirichlet-multinomial distribution with mi trials for sample i. The term −ln(|α| + k) occurs in the log-likelihood for xi if and only if mi ≥ k + 1. Likewise the term ln(αj + k) occurs in the log-likelihood for xi if and only if xij ≥ k + 1. It follows that the log-likelihood for the entire sample can be written as

| (3.4) |

The index k in these formulas ranges from 0 to maxi mi −1.

Applying our two basic minorizations to L(α) yields the surrogate function

up to an irrelevant additive constant. Equating the partial derivative of the surrogate with respect to αj to 0 produces the simple MM update

| (3.5) |

Minka (2003) derived these updates from a different perspective.

Under the parameterization (3.3), matters are slightly more complicated. Now we minorize the terms −ln(1 + kθ) and ln(πj + kθ) via

and

These minorizations lead to the surrogate function

up to an irrelevant constant. Setting the partial derivative with respect to θ equal to 0 yields the MM update

| (3.6) |

The update of the proportion vector π must be treated as a Lagrange multiplier problem owing to the constraint Σj πj = 1. Familiar arguments produce the MM update

| (3.7) |

The two updates summarized by (3.5), (3.6), and (3.7) enjoy several desirable properties. First, parameter constraints are built in. Second, stationary points of the log-likelihood are fixed points of the updates. Virtually all MM algorithms share these properties. The update (3.7) also reduces to the maximum likelihood estimate

| (3.8) |

of the corresponding multinomial proportion when θn = 0.

The estimate (3.8) furnishes a natural initial value . To derive an initial value for the overdispersion parameter θ, consider the first two moments

of a Dirichlet distribution with parameter vector α. These identities imply that

which can be solved for θ = 1/|α| in terms of ρ as θ = (ρ − 1)/(d − ρ). Substituting the estimate

for ρ gives a sensible initial value θ0.

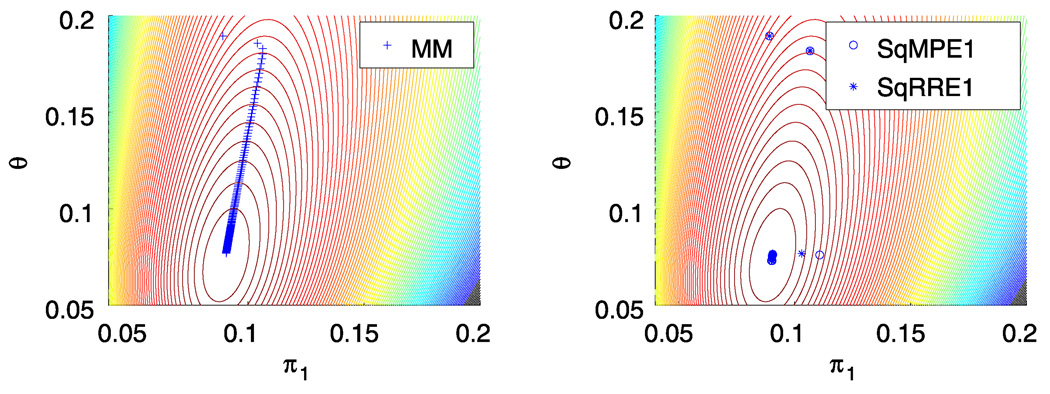

To test our two MM algorithms, we now turn to the beta-binomial data of Haseman and Soares (1976) on male mice exposed to various mutagens. The two outcome categories are (a) dead implants and (b) survived implants. In their first dataset, there are t = 524 observations with between m = 1 and m = 20 trials per observation. Table 1 presents the final log-likelihood, number of iterations, and running time (in seconds) of the two MM algorithms and their SQUAREM accelerations on these data. All MM algorithms converge to the maximum point previously found by the scoring method (Paul, Balasooriya, and Banerjee 2005). For the choice ε = 10−9 in stopping criterion (2.6), the MM algorithm (3.5) takes 700 iterations and 0.1580 sec to converge on a laptop computer. The alternative MM algorithm given in the updates (3.6) and (3.7) takes 339 iterations and 0.1626 sec. Figure 1 depicts the progress of the MM iterates on a contour plot of the log-likelihood. The conventional MM algorithm crawls slowly along the ridge in the contour plot; the accelerated versions SqMPE1 and SqRRE1 significantly reduce both the number of iterations and the running time until convergence.

Table 1.

MM algorithms for the Haseman and Soares beta-binomial data.

| (π, θ) parameterization | α parameterization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Algorithm | L | # iters | Time | L | # iters | Time |

| MM | −777.79 | 339 | 0.1626 | −777.79 | 700 | 0.1580 |

| SqMPE1 MM | −777.79 | 10 | 0.0093 | −777.79 | 14 | 0.0105 |

| SqRRE1 MM | −777.79 | 18 | 0.0159 | −777.79 | 14 | 0.0100 |

Figure 1.

MM Ascent of the Dirichlet-multinomial log-likelihood surface. A color version of this figure is available in the electronic version of this article.

The Dirichlet-multinomial distribution suffers from two restrictions that limit its applicability, namely the negative correlation of coordinates and the determination of variances by means. It is possible to overcome these restrictions by choosing a more flexible mixing distribution as a prior for the multinomial. Connor and Mosimann (1969) suggested a generalization of the Dirichlet distribution that meets this challenge. The resulting admixed distribution, called the generalized Dirichlet-multinomial distribution, has proved its worth in machine learning problems such as the modeling and clustering of images, handwritten digits, and text documents (Bouguila 2008). It is therefore helpful to derive an MM algorithm for maximum likelihood estimation with this distribution that avoids the complications of gamma/digamma/trigamma functions arising with Newton’s method (Bouguila 2008). The Connor–Mosimann distribution is constructed inductively by the mechanism of stick breaking. Imagine breaking the interval [0, 1] into d subintervals of lengths P1,…, Pd by choosing d − 1 independent beta variates Zi with parameters αi and βi. The length of subinterval 1 is P1 = Z1. Given P1 through Pi, the length of subinterval i + 1 is Pi+1 = Zi+1(1 − P1 − ⋯−Pi). The last length Pd = 1 − (P1 + ⋯ + Pd−1) takes up the slack. Standard calculations show that the Pi have the joint density

where γj = βj − αj+1 − βj+1 for j = 1,…, d − 2 and γd−1 = βd−1 − 1. The univariate case (d = 2) corresponds to the beta distribution. The Dirichlet distribution is recovered by taking βj = αj+1 +⋯+αd. With d − 2 more parameters than the Dirichlet distribution, the Connor–Mosimann distribution is naturally more versatile.

The Connor–Mosimann distribution is again conjugate to the multinomial distribution, and the marginal density of a count vector X over m trials is easily shown to be

where . If we adopt the reparameterization

and use the fact that xj + yj+1 = yj, then the density can be re-expressed as

| (3.9) |

Thus, maximum likelihood estimation of the parameter vectors π = (π1,…, πd−1) and θ = (θ1,…, θd−1) by the MM algorithm reduces to the case of d − 1 independent beta-binomial problems.

Let x1,…, xt be a random sample from the generalized Dirichlet-multinomial distribution (3.9) with mi trials for observation xi. Following our reasoning for estimation with the Dirichlet-multinomial, we define the associated counts

for 1 ≤ j ≤ d − 1. In this notation, the reader can readily check that the MM updates become

3.2 Neerchal–Morel Distribution

Neerchal and Morel (1998, 2005) proposed an alternative to the Dirichlet-multinomial distribution that accounts for overdispersion by finite admixture. If x represents count data over m trials and d categories, then their discrete density is

| (3.10) |

where π = (π1,…, πd) is a vector of proportions and ρ ∈ [0, 1] is an overdispersion parameter. The Neerchal–Morel distribution collapses to the multinomial distribution when ρ = 0. Straightforward calculations show that the Neerchal–Morel distribution has means, variances, and covariances

These are precisely the same as the first- and second-order moments of the Dirichlet-multinomial distribution provided we identify πi = αi/|α| and ρ2 = 1/(|α| + 1).

If we draw t independent samples x1,…, xt from the Neerchal–Morel distribution with mi trials for sample i, then the log-likelihood is

| (3.11) |

It is worth bearing in mind that every mixture model yields to the minorization (2.3). This is one of the secrets to the success of the EM algorithm. As a practical matter, explicit minorization via inequality (2.3) is more mechanical and often simpler to implement than performing the E step of the EM algorithm. This is particularly true when several minorizations intervene before we reach the ideal surrogate. Here two successive minorizations are needed.

To state the first minorization, let us abbreviate

and denote by the same quantity evaluated at the nth iterate. In this notation it follows that

with weights . The logarithm splits ln ∏ij into the sum

for θ = ρ/(1 − ρ). To separate the parameters πj and θ in the troublesome term ln(πj + θ), we apply the minorization (2.3) again. This produces

and up to a constant the surrogate function takes the form

Standard arguments now yield the updates

Table 2 lists convergence results for this MM algorithm and its SQUAREM accelerations on the previously discussed Haseman and Soares data.

Table 2.

Performance of the Neerchal–Morel MM algorithms.

| Algorithm | L | # iters | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| MM | −783.29 | 128 | 0.2289 |

| SqMPE1 MM | −783.29 | 10 | 0.0207 |

| SqRRE1 MM | −783.29 | 11 | 0.0221 |

3.3 Negative-Multinomial

The motivation for the negative-multinomial distribution comes from multinomial sampling with d + 1 categories assigned probabilities π1,…, πd+1. Sampling continues until category d + 1 accumulates β outcomes. At that moment we count the number of outcomes xi falling in category i for 1 ≤ i ≤ d. For a given vector x = (x1,…, xd ), elementary combinatorics gives the probability

| (3.12) |

This formula continues to make sense even if the positive parameter β is not an integer. For arbitrary β > 0, the most straightforward way to construct the negative-multinomial distribution is to run d independent Poisson processes with intensities π1,…, πd. Wait a gamma distributed length of time with shape parameter β and intensity parameter πd+1. At the expiration of this waiting time, count the number of random events Xi of each type i among the first d categories. The random vector X has precisely the discrete density (3.12).

The Poisson process perspective readily yields the moments

| (3.13) |

Compared to a Poisson distributed random variable with the same mean, the component Xi is overdispersed. Also in contrast to the multinomial and Dirichlet-multinomial distributions, the counts from a negative-multinomial are positively correlated. Negative-multinomial sampling is therefore appealing in many applications.

Let x1,…, xt be a random sample from the negative-multinomial distribution with mi = |xi|. To maximize the log-likelihood

we must deal with the terms ln(β + k). Fortunately, the minorization (2.4) implies

leading to the surrogate function

up to an irrelevant constant. In view of the constraint the stationarity conditions for a maximum of the surrogate reduce to

| (3.14) |

Unfortunately, it is impossible to solve this system of equations analytically. There are two resolutions to the dilemma. One is block relaxation (de Leeuw 1994) alternating the updates

and

This strategy enjoys the ascent property of all MM algorithms.

The other possibility is to solve the stationarity equations numerically. It is clear that the system of equations (3.14) reduces to the single equation

for β. Equivalently, if we let

then we must find a root of the equation f (α) = αcn − t ln(αm̄ + 1) = 0. It is clear that f (α) is a strictly convex function with f (0) = 0 and limα→∞ f (α) = ∞. Furthermore, a little reflection shows that f′ (0) = cn −tm̄ < 0. Thus, there is a single root of f (α) on the interval (0,∞). Owing to the convexity of f (α), Newton’s method will reliably find the root if started to the right of the minimum of f (α) at α = t/cn − 1/m̄.

To find initial values, we again resort to the method of moments. Based on the moments (3.13), the mean and variance of |X| = Σk Xj are

These suggest that we take

where

When the data are underdispersed (s2 < x̄), our proposed initial values are not meaningful, but a negative-multinomial model is a poor choice anyway.

3.4 Distributions on Partitions

A partition of a positive integer m into k parts is a vector a = (a1,…, am) of non-negative integers such that Σi ai = k and |a| = Σi iai = m. In population genetics, the partition distributions of Ewens (2004) and Pitman (Pitman 1995; Johnson, Kotz, and Balakrishnan 1997) find wide application. We now develop an MM algorithm for Pitman’s distribution, which generalizes Ewens’s distribution. Pitman’s distribution

involves two parameters 0 ≤ α < 1 and θ > −α. Ewens’s distribution corresponds to the choice α = 0. We will restrict θ to be positive.

To estimate parameters given u independent partitions a1,…, au from Pitman’s distribution, we use the minorizations (2.3) and (2.4) to derive the minorizations

where c is a different irrelevant constant in each case. Assuming aj is a partition of the integer mj, it follows that the log-likelihood is minorized by

where

Standard arguments now yield the simple updates

If we set α0 = 0, then in all subsequent iterates αn = 0, and we get the MM updates for Ewens’s distribution. Despite the availability of the moments of the parts Ai (Charalambides 2007), it is not clear how to initialize α and θ. Unfortunately, the alternative suggestion of Nobuaki (2001) does not guarantee that the initial values satisfy the constraints α ∈ [0, 1) and θ > 0.

3.5 Zero-Truncated and Zero-Inflated Data

In this section we briefly indicate how the MM perspective sheds fresh light on EM algorithms for zero-truncated and zero-inflated data. Once again mastery of a handful of inequalities rather than computation of conditional expectations drives the derivations.

In many discrete probability models, only data with positive counts are observed. Counts that are 0 are missing. If f (x|θ) represents the density of the complete data, then the density of a random sample x1,…, xt of zero-truncated data amounts to

Inequality (2.5) immediately implies the minorization

where c is an irrelevant constant. In many models, maximization of this surrogate function is straightforward.

For instance, with zero-truncated data from the binomial, Poisson, and negative-binomial distributions, the MM updates reduce to

For observation i of the binomial model, there are xi successes out of mi trials with success probability p per trial. λ is the mean in the Poisson model. For observation i of the negative-binomial model, there are xi failures before mi required successes.

More complicated models can be handled in similar fashion. The key insight in each case is to augment every ordinary observation xi > 0 by a total of f (0|θn)/[1 − f (0|θn)] pseudo-observations of 0 at iteration n. With this amendment, the two MM algorithms for the beta-binomial distribution implemented in (3.5), (3.6), and (3.7) remain valid except that the count variables rk and sjk defining the updated parameters at iteration n become

where

Here category 1 represents success and category 2 failure. If we start with θ0 = 0, then we recover the updates for the zero-truncated binomial distribution.

Zero-inflated data are equally easy to handle. The density function is now

Inequality (2.3) entails the minorization

The MM update of the inflation-admixture parameter clearly is

As a typical example, consider estimation with the zero-inflated Poisson (Patil 2007). The mean λ of the Poisson component is updated by

In other words, every 0 observation is discounted by the amount zn at iteration n. This makes intuitive sense.

4. A NUMERICAL EXPERIMENT

As a numerical experiment, we fit the Dirichlet-multinomial (two parameterizations) and the Neerchal–Morel distributions to the 3823 training digits in the handwritten digit data from the UCI machine learning repository (Asuncion and Newman 2007). Each normalized 32 × 32 bitmap is divided into 64 blocks of size 4 × 4, and the black pixels are counted in each block. This generates a 64-dimensional count vector for each bitmap. Bouguila (2008) successfully fit mixtures of Connor–Mosimann to the training data and used the estimated models to cluster the test data. For illustrative purposes we now fit the Dirichlet-multinomial (two parameterizations) and Neerchal–Morel models. Based on the majorization (2.3), it is straightforward to extend our MM algorithms to fit finite mixture models using any of the previously encountered multivariate discrete distributions.

Table 3 lists the final log-likelihoods, number of iterations, and running times of the different algorithms tested. The MM and accelerated MM algorithms were coded in plain Matlab script language. Newton’s method was implemented using the fmincon function in the Marla Optimization Toolbox under the interior-point option with user-supplied analytical gradient and Hessian. All iterations started from the initial points θ0 = 1 and . The stopping criterion for Newton’s method was tuned to achieve precision comparable to the stopping criterion (2.6) for the MM algorithms. Running times in seconds were recorded from a laptop computer.

Table 3.

Numerical experiment. Row 1: MM; Row 2: SqMPE1 MM; Row 3: SqRRE1 MM; Row 4: Newton’s method using the (fmincon) function available in the Matlab Optimization Toolbox.

| DM (π, θ) | DM (α) | Neerchal–Morel | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Digit | L | # iters | Time | L | # iters | Time | L | iters | Time |

| 0 | −37,358 | 232 | 0.18 | −37,358 | 361 | 0.16 | −38,828 | 15 | 0.08 |

| −37,358 | 18 | 0.04 | −37,358 | 18 | 0.04 | −38,828 | 7 | 0.10 | |

| −37,358 | 21 | 0.04 | −37,358 | 18 | 0.04 | −38,828 | 7 | 0.09 | |

| −37,359 | 11 | 0.13 | −37,358 | 18 | 0.16 | −38,828 | 13 | 106.42 | |

| 1 | −42,179 | 237 | 0.16 | −42,179 | 120 | 0.06 | −52,424 | 17 | 0.09 |

| −42,179 | 17 | 0.03 | −42,179 | 12 | 0.03 | −52,424 | 7 | 0.10 | |

| −42,179 | 26 | 0.05 | −42,179 | 13 | 0.03 | −52,424 | 7 | 0.10 | |

| −42,179 | 15 | 0.19 | −42,179 | 14 | 0.13 | −52,424 | 12 | 98.91 | |

| 2 | −39,985 | 213 | 0.14 | −39,985 | 136 | 0.07 | −47,723 | 14 | 0.07 |

| −39,985 | 17 | 0.04 | −39,985 | 15 | 0.03 | −47,723 | 6 | 0.08 | |

| −39,985 | 17 | 0.04 | −39,985 | 11 | 0.03 | −47,723 | 6 | 0.08 | |

| −39,986 | 15 | 0.19 | −39,985 | 15 | 0.13 | −47,721 | 14 | 113.15 | |

| 3 | −40,519 | 214 | 0.14 | −40,519 | 173 | 0.08 | −45,816 | 14 | 0.07 |

| −40,519 | 23 | 0.04 | −40,519 | 15 | 0.03 | −45,816 | 6 | 0.08 | |

| −40,519 | 20 | 0.04 | −40,519 | 11 | 0.03 | −45,816 | 6 | 0.08 | |

| −40,519 | 14 | 0.17 | −40,519 | 15 | 0.13 | −45,816 | 12 | 102.30 | |

| 4 | −43,489 | 203 | 0.13 | −43,489 | 102 | 0.06 | −55,432 | 14 | 0.07 |

| −43,489 | 17 | 0.04 | −43,489 | 12 | 0.03 | −55,432 | 6 | 0.08 | |

| −43,489 | 19 | 0.04 | −43,489 | 9 | 0.03 | −55,432 | 6 | 0.08 | |

| −43,489 | 13 | 0.17 | −43,489 | 14 | 0.12 | −55,432 | 14 | 114.40 | |

| 5 | −41,191 | 205 | 0.13 | −41,191 | 116 | 0.06 | −50,063 | 13 | 0.07 |

| −41,191 | 18 | 0.04 | −41,191 | 12 | 0.03 | −50,063 | 6 | 0.08 | |

| −41,191 | 19 | 0.04 | −41,191 | 12 | 0.03 | −50,063 | 6 | 0.09 | |

| −41,192 | 12 | 0.16 | −41,191 | 15 | 0.13 | −50,063 | 15 | 118.22 | |

| 6 | −37,703 | 232 | 0.15 | −37,703 | 203 | 0.10 | −41,888 | 20 | 0.10 |

| −37,703 | 19 | 0.04 | −37,703 | 16 | 0.03 | −41,888 | 8 | 0.11 | |

| −37,703 | 21 | 0.04 | −37,703 | 11 | 0.03 | −41,888 | 8 | 0.11 | |

| −37,703 | 15 | 0.19 | −37,703 | 19 | 0.16 | −41,888 | 13 | 104.25 | |

| 7 | −40,304 | 218 | 0.14 | −40,304 | 141 | 0.07 | −47,653 | 12 | 0.06 |

| −40,304 | 16 | 0.04 | −40,304 | 15 | 0.03 | −47,653 | 6 | 0.08 | |

| −40,304 | 18 | 0.04 | −40,304 | 11 | 0.03 | −47,653 | 6 | 0.08 | |

| −40,305 | 13 | 0.15 | −40,304 | 15 | 0.13 | −47,653 | 15 | 120.95 | |

| 8 | −43,131 | 227 | 0.15 | −43,131 | 171 | 0.08 | −48,844 | 17 | 0.09 |

| −43,131 | 19 | 0.04 | −43,131 | 16 | 0.03 | −48,844 | 7 | 0.10 | |

| −43,131 | 23 | 0.04 | −43,131 | 14 | 0.03 | −48,844 | 7 | 0.09 | |

| −43,132 | 10 | 0.13 | −43,131 | 15 | 0.14 | −48,844 | 13 | 107.22 | |

| 9 | −43,710 | 207 | 0.14 | −43,710 | 116 | 0.06 | −53,030 | 13 | 0.07 |

| −43,710 | 19 | 0.04 | −43,710 | 12 | 0.03 | −53,030 | 6 | 0.08 | |

| −43,710 | 18 | 0.04 | −43,710 | 11 | 0.03 | −53,030 | 6 | 0.08 | |

| −43,710 | 12 | 0.16 | −43,710 | 15 | 0.14 | −53,030 | 14 | 116.49 | |

Inspection of Table 3 demonstrates that the MM algorithms outperform Newton’s method and that acceleration is often very beneficial. The cost of evaluating and inverting the observed information matrices of the Neerchal–Morel model significantly slows Newton’s method even in these problems with only 64 parameters. The observed information matrix of the Dirichlet-multinomial distribution possesses a special structure (diagonal plus rank-1 perturbation) that makes matrix inversion far easier. Table 3 does not show the human effort in devising, programming, and debugging the various algorithms. For Newton’s method, derivation and programming took in excess of one day. Formulas for the score and observed information of the Dirichlet-multinomial and Neerchal–Morel distributions are omitted for the sake of brevity. Fisher’s scoring algorithm was not implemented because it is even more cumbersome than Newton’s method (Neerchal and Morel 2005).

This numerical comparison is merely for illustrative purpose. Numerical analysts have developed quasi-Newton algorithms to mend the defects of Newton’s method. The limited-memory BFGS (LBFGS) algorithm (Nocedal and Wright 2006) is especially pertinent to high-dimensional problems. A systematic comparison of the two methods is worth pursuing.

5. DISCUSSION

In designing algorithms for maximum likelihood estimation, Newton’s method and Fisher scoring come immediately to mind. In the last generation, statisticians have added the EM principle. These are good mental reflexes, but the broader MM principle also deserves serious consideration. In many problems, the EM and MM perspectives lead to the same algorithm. In other situations such as image reconstruction in transmission tomography, it is possible to construct different EM and MM algorithms for the same purpose (Lange 2004). One of the most appealing features of the EM perspective is that it provides a statistical interpretation of algorithm intermediates. Although it is a matter of taste and experience whether inequalities or missing data offer an easier path to algorithm development, the fact that there are two routes adds to the possibilities for new algorithms.

One can argue that applications of minorizations (2.3) and (2.5) are just disguised EM algorithms. This objection misses the point in three ways. First, it does not suggest missing data structures explaining the minorization (2.4) and other less well-know minorizations. Second, it fails to weigh the difficulties of invoking simple inequalities versus calculating conditional expectations. When the creation of an appropriate surrogate function requires several minorizations, the corresponding conditional expectations become harder to execute. For example, although the EM principle dictates adding pseudo-observations for zero-truncated data, it is easy to lose sight of this simple interpretation in complicated examples such as the beta-binomial distribution. The genetic segregation analysis example appearing in chapter 2 of the book by Lange (2002) falls into the same category. Third, it fails to acknowledge the conceptual clarity of the MM principle, which shifts focus away from the probability spaces connected with missing data to the simple act of minorization. For instance, when one undertakes maximum a posteriori estimation, should the E step of the EM algorithm take into account the prior?

Some EM and MM algorithms are notoriously slow to converge. As we noted earlier, slow convergence is partially offset by the simplicity of each iteration. There is a growing body of techniques for accelerating MM algorithms (Jamshidian and Jennrich 1995; Lange 1995a; Jamshidian and Jennrich 1997; Varadhan and Rolland 2008). These techniques often lead to a ten-fold or even a hundred-fold reduction in the number of iterations. The various examples appearing in this article are typical in this regard. On problems with boundaries or nondifferentiable objective functions, acceleration may be less helpful.

Our negative-multinomial example highlights two useful tactics for overcoming complications in solving the maximization step of the EM and MM algorithms. It is a mistake to think of the various optimization algorithms in isolation. Often block relaxation (de Leeuw 1994) and Newton’s method can be combined creatively with the MM principle. Systematic application of Newton’s method in solving the maximization step of the MM algorithm is formalized in the MM gradient algorithm (Lange 1995b).

Parameter asymptotic standard errors are a natural byproduct of Newton’s method and scoring. With a modicum of additional effort, the EM and MM algorithms also deliver asymptotic standard errors (Meng and Rubin 1991; Hunter and Lange 2004). Virtually all optimization algorithms are prone to converge to inferior modes. For this reason, we have emphasized finding reasonable initial values. The overlooked article of Ueda and Nakano (1998) suggested an annealing approach to maximization with mixture models. Here the idea is to flatten the likelihood surface and eliminate all but the dominant mode. As the iterations proceed, the flat surface gradually warps into the true bumpy surface. Our recent work (Zhou and Lange 2010) extends this idea to many other EM and MM algorithms. A similar idea, called graduated non-convexity (GNC), appears in computer vision and signal processing literature (Blake and Zisserman 1987). In the absence of a good annealing procedure, one can fall back on starting an optimization algorithm from multiple random points, but this inevitably increases the computational load. The reassurance that a log-likelihood is concave is always welcome.

Readers may want to try their hands at devising their own MM algorithms. For instance, the Dirichlet-negative-multinomial distribution, the bivariate Poisson (Johnson, Kotz, and Balakrishnan 1997), and truncated multivariate discrete distributions yield readily to the techniques described. The performance of the MM algorithm on these problems is similar to that in our fully developed examples. Of course, many objective functions are very complicated, and devising a good MM algorithm is a challenge. The greatest payoffs are apt to be on high-dimensional problems. For simplicity of exposition, we have not tackled any extremely high-dimensional problems, but these certainly exist (Sabatti and Lange 2002; Ayers and Lange 2008; Lange and Wu 2008). In any event, most mathematicians and statisticians keep a few tricks up their sleeves. The MM principle belongs there, waiting for the right problems to come along.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the editors and referees for their many valuable comments.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS

Datasets and Matlab codes: The supplementary material (a single zip package) contains all datasets appearing here and the Matlab codes generating our numerical results and graphs. The readme.txt file describes the contents of each file in the package. (supp_material.zip)

Contributor Information

Hua Zhou, Post-Doctoral Fellow, Department of Human Genetics, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-7088 (huazhou@ucla.edu)..

Kenneth Lange, Professor, Departments of Biomathematics, Human Genetics, and Statistics, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-7088..

REFERENCES

- Asuncion A, Newman DJ. (UCI) Machine Learning Repository. 2007 available at http://www.ics.uci.edu/~mlearn/Repository.html. [Google Scholar]

- Ayers KL, Lange K. Penalized Estimation of Haplotype Frequencies. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1596–1602. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey NTJ. The Mathematical Theory of Epidemics. London: Charles Griffin & Company; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Blake A, Zisserman A. Visual Reconstruction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bouguila N. Clustering of Count Data Using Generalized Dirichlet Multinomial Distributions. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering. 2008;20(4):462–474. [Google Scholar]

- Charalambides CA. Distributions of Random Partitions and Their Applications. Methodology and Computing in Applied Probability. 2007;9:163–193. [Google Scholar]

- Connor RJ, Mosimann JE. Concepts of Independence for Proportions With a Generalization of the Dirichlet Distribution. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1969;64:194–206. [Google Scholar]

- Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum Likelihood From Incomplete Data via the EM Algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Ser. B. 1977;39(1):1–38. (with discussion) [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw J. Block Relaxation Algorithms in Statistics. In: Bock HH, Lenski W, Richter MM, editors. Information Systems and Data Analysis. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ewens WJ. Mathematical Population Genetics. 2nd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths DA. Maximum Likelihood Estimation for the Beta-Binomial Distribution and an Application to the Household Distribution of the Total Number of Cases of a Disease. Biometrics. 1973;29:637–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenen PJF. The Majorization Approach to Multidimensional Scaling: Some Problems and Extensions. Leiden: The Netherlands: DSWO Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Haldane JBS. The Fitting of Binomial Distributions. Annals of Eugenics. 1941;11:179–181. [Google Scholar]

- Haseman JK, Soares ER. The Distribution of Fetal Death in Control Mice and Its Implications on Statistical Tests for Dominant Lethal Effects. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 1976;41:277–288. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(76)90101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiser WJ. Convergent Computing by Iterative Majorization: Theory and Applications in Multidimensional Data Analysis. In: Krzanowski WJ, editor. Recent Advances in Descriptive Multivariate Analysis. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1995. pp. 157–189. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter DR, Lange K. A Tutorial on MM Algorithms. The American Statistician. 2004;58:30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Jamshidian M, Jennrich RI. Acceleration of the EM Algorithm by Using Quasi-Newton Methods. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Ser. B. 1995;59:569–587. [Google Scholar]

- Jamshidian M, Jennrich RI. Quasi-Newton Acceleration of the EM Algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Ser. B. 1997;59:569–587. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson NL, Kotz S, Balakrishnan N. Discrete Multivariate Distributions. New York: Wiley; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lange K. A Quasi-Newton Acceleration of the EM Algorithm. Statistica Sinica. 1995a;5:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lange K. A Gradient Algorithm Locally Equivalent to the EM Algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Ser. B. 1995b;57(2):425–437. [Google Scholar]

- Lange K. Mathematical and Statistical Methods for Genetic Analysis. 2nd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lange K. Optimization. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lange K, Wu TT. An MM Algorithm for Multicategory Vertex Discriminant Analysis. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 2008;17:527–544. [Google Scholar]

- Meng XL, Rubin DB. Using EM to Obtain Asymptotic Variance–Covariance Matrices: The SEM Algorithm. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1991;86:899–909. [Google Scholar]

- Minka TP. Estimating a Dirichlet Distribution. Technical report, Microsoft. 2003

- Neerchal NK, Morel JG. Large Cluster Results for Two Parametric Multinomial Extra Variation Models. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1998;93(443):1078–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Neerchal NK, Morel JG. An Improved Method for the Computation of Maximum Likelihood Estimates for Multinomial Overdispersion Models. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 2005;49(1):33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nobuaki H. Applying Pitman’s Sampling Formula to Microdata Disclosure Risk Assessment. Journal of Official Statistics. 2001;17:499–520. [Google Scholar]

- Nocedal J, Wright S. Numerical Optimization. New York: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Patil MK, Shirke DT. Testing Parameter of the Power Series Distribution of a Zero Inflated Power Series Model. Statistical Methodology. 2007;4:393–406. [Google Scholar]

- Paul SR, Balasooriya U, Banerjee T. Fisher Information Matrix of the Dirichlet-Multinomial Distribution. Biometrical Journal. 2005;47(2):230–236. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200410103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitman J. Exchangeable and Partially Exchangeable Random Partitions. Probability Theory and Related Fields. 1995;102(2):145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatti C, Lange K. Genomewide Motif Identification Using a Dictionary Model. Proceedings of the IEEE. 2002;90:1803–1810. [Google Scholar]

- Steele JM. The Cauchy–Schwarz Master Class. MAA Problem Books Series. Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda N, Nakano R. Deterministic Annealing EM Algorithm. Neural Networks. 1998;11:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s0893-6080(97)00133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadhan R, Roland C. Simple and Globally Convergent Methods for Accelerating the Convergence of Any EM Algorithm. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 2008;35:335–353. [Google Scholar]

- Wu TT, Lange K. The MM Alternative to EM. Statistical Science. 2010 to appear. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Lange K. On the Bumpy Road to the Dominant Mode. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9469.2009.00681.x. to appear. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.